Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (vATTR) is a progressive genetic disorder with several approved treatments. We investigated treatment responses to tafamidis and patisiran in vATTR patients to identify predictive response factors.

MethodsRetrospective analysis on vATTR patients treated with tafamidis or patisiran from October 2012 to September 2022. Treatment responses were assessed as “good,” “partial,” or “non-response.” We analysed pre-treatment clinical and laboratory data to identify predictors of treatment response.

ResultsOf the 53 patients, 44 received tafamidis and 23 received patisiran; 14 were treated with both drugs sequentially. Predictors of good response to tafamidis were shorter diagnostic delay (≤1 year), less severe neurological impairment (Coutinho stage 1, Neuropathy Impairment Score [NIS]≤7), and better sudomotor function in the feet (≥50μS) before treatment. Factors associated with non-response were greater disability (baseline Polyneuropathy Disability score=2), large fibre involvement, and significant weight loss. Predictors of a good response to patisiran included lower pre-treatment disease severity (Coutinho stage 1, NIS≤40). We propose an individualised therapeutic approach using predictive factors to guide initial treatment.

ConclusionsThis study identifies predictive factors for response to tafamidis and patisiran in vATTR patients, highlighting baseline NIS as a critical predictor. We propose a novel therapeutic algorithm for personalised treatment strategies with potential to avoid years of ineffective treatment.

La amiloidosis hereditaria por transtirretina (ATTRv) es una enfermedad genética progresiva para la que existen varios tratamientos. Este estudio analiza la respuesta a tafamidis y patisirán en pacientes con ATTRv con el propósito de identificar predictores de respuesta al tratamiento.

MétodoRealizamos un estudio retrospectivo de pacientes con ATTRv tratados con tafamidis o patisirán entre octubre de 2012 y septiembre de 2022. La respuesta al tratamiento se clasificó como «adecuada», «parcial» o «sin respuesta». Analizamos variables clínicas y analíticas antes del tratamiento para identificar predictores de respuesta al mismo.

ResultadosIncluimos un total de 53 pacientes: 44 en tratamiento con tafamidis y 23 en tratamiento con patisirán (14 fueron tratados con ambos fármacos de forma secuencial). Los predictores de respuesta adecuada a tafamidis fueron menor retraso diagnóstico (≤1 año), menor gravedad del deterioro neurológico (estadio 1 de Coutinho, Neuropathy Impairment Score≤7) y mejor función sudomotora en los pies (≥50μS) antes del tratamiento. Los factores asociados a la ausencia de respuesta a tafamidis fueron mayor discapacidad (puntuación en la escala Polyneuropathy Disability de 2 al inicio), afectación de fibras gruesas y pérdida de peso significativa. Entre los predictores de respuesta adecuada a patisirán se encuentra una menor gravedad de la enfermedad antes del tratamiento (estadio 1 de Coutinho, Neuropathy Impairment Score≤40). Proponemos una aproximación terapéutica individualizada basada en factores predictivos para guiar el tratamiento inicial.

ConclusionesEste estudio identifica predictores de respuesta a tafamidis y patisirán en pacientes con ATTRv, entre los que destaca la puntuación en la Neuropathy Impairment Score al inicio. Proponemos un algoritmo terapéutico novedoso para personalizar la estrategia terapéutica y evitar años de tratamiento ineficaz.

Hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (vATTR) is an infiltrative genetic disease with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. vATTR is caused by mutations within the TTR gene, which encodes the transthyretin (TTR) protein. This protein plays a critical role in the transport of thyroxine (T4) and retinol (vitamin A) through the bloodstream.1 Mutations in TTR cause structural changes in the protein, leading to the formation of amyloid aggregates. This abnormal protein accumulates in many organs, resulting in a wide range of symptoms.

Worldwide, vATTR has a low prevalence, with approximately one case per million population. However, this frequency is higher in endemic areas, such as Portugal, Japan, and certain regions of Spain, where it can affect up to one in 1000 people. Over 130 different pathogenic TTR mutations have been identified, with the Val50Met mutation (previously known as Val30Met) being the most common, accounting for almost 60% of all cases.2

The disease presents with a wide spectrum of phenotypes that are strongly influenced by mutation type, age of onset, and geographic location. vATTR symptoms can occur at any age, typically between the second and ninth decades of life. Interestingly, not all carriers of pathogenic TTR mutations develop the disease, due to the phenomenon known as incomplete penetrance.3–5 Predominant clinical manifestations include polyneuropathy (vATTR-PN), cardiomyopathy (vATTR-CM), or mixed phenotypes. In addition, organ-specific variants of the disease have been reported with ocular, renal, or leptomeningeal manifestations.6–8 In particular, peripheral neuropathy and cardiac disease contribute the most to the high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with the disease. Likewise, vATTR is associated with a significantly reduced life expectancy, approximately 10 years after diagnosis, ranging from 7 to 12 years, depending on the specific mutation involved, the predominant phenotype, and the geographical location of the patient.7

Despite the poor prognosis, several effective treatments are available. Although they do not offer a cure, they are able to stabilise and potentially slow the progression of the disease.9,10 The treatment landscape for vATTR has evolved significantly, with 4 drugs (tafamidis, patisiran, inotersen, and vutrisiran) currently approved for the treatment of early-stage vATTR. These drugs have unique modes of action, providing clinicians with a broader armamentarium for disease management.11–21 However, selecting the most appropriate therapeutic option for each patient remains a significant clinical challenge, given the multifaceted nature of the disease.

Tafamidis, a stabilising molecule, is indicated for Coutinho stage I patients who are able to walk unassisted.12 Many authors consider tafamidis to be the first-line therapy for vATTR,13 and studies suggest that this treatment is most effective in the least affected individuals within this category.14–18 Patisiran is a small interfering RNA (siRNA) that inhibits hepatic synthesis of the TTR protein.19 It is indicated for patients in Coutinho stages 1 and 2, which include people who can walk with or without assistance. The third treatment, inotersen, is an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits the hepatic synthesis of TTR,20 and is also indicated for patients in Coutinho stages 1 and 2. Finally, vutrisiran, a second-generation siRNA approved in 2022, works similarly to patisiran.21 Its improved design, conjugated to an N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) ligand, allows for higher affinity for hepatocyte-specific receptors, promoting more efficient delivery to the liver. Like the 2 previous treatments, vutrisiran is approved for patients in Coutinho stages 1 and 2.21

With multiple treatment options available in the early stages of the disease, it is critical to investigate factors that predict response to each of these treatments. However, research on this topic is limited, especially in non-endemic regions where patients have different phenotypes, mutations, and clinical presentations.

Our study aims to investigate a wide range of demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables to identify potential predictive factors for treatment response to tafamidis and patisiran. This research has the potential to significantly improve clinical decision-making and enable more effective treatment selection for patients with vATTR.

MethodsStudy populationWe performed a retrospective analysis of our cohort of patients with vATTR treated with tafamidis or patisiran at our institution between October 2012 and September 2022. Inclusion criteria were confirmed TTR mutation, stage 1 or 2 vATTR neuropathy according to Coutinho staging, treatment with either tafamidis or patisiran for at least 6 months at any point in the disease course, and follow-up at our neuromuscular diseases unit. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was approved by our hospital's ethics committee (ref C.I. 22/480-O_M_NoSP) and complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collectionComprehensive data were extracted from patients’ clinical records, including demographic, clinical, and laboratory data. Baseline parameters, collected prior to treatment initiation, included clinical manifestations and such neurophysiological parameters as nerve conduction studies, sympathetic skin response, and R-R interval variability. Parameters collected both at baseline and every 6 months during follow-up included Coutinho stage; Polyneuropathy Disability (PND) score; New York Heart Association (NYHA) class; Gillmore/National Amyloidosis Centre (NAC) stage; sudomotor function as measured with the Sudoscan device; Neuropathy Impairment Score (NIS), derived from neurological assessment of sensorimotor function and reflexes by a trained neurologist; patient-reported outcomes using the Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31 (COMPASS-31) scale, Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy (QOL-DN) questionnaire, and Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale (RODS); Karnofsky Performance Status Scale; and laboratory parameters including serum levels of TTR, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), vitamin A, vitamin D, retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), and uric acid.

Evaluation of treatment responseGiven the multifaceted complexity of vATTR, it is not possible to definitively estimate disease response using a single outcome measure. Therefore, treatment response criteria were based on assessment by an expert neurologist, both at baseline and during patient follow-up until the last visit or the end of treatment.

Patients were classified as good responders if they showed no motor or sensory worsening on the NIS scale, remained stable in terms of Coutinho and PND staging, and showed no progression in dysautonomic symptoms or neurophysiological parameters. Partial responders were those with slow motor or sensory progression on the NIS scale (<4 points at 2 consecutive visits) but with either stable or improving dysautonomic symptoms. The criteria for classifying patients as non-responders were confirmed worsening on the NIS scale (>4 points at 2 consecutive visits), worsening of Coutinho or PND stage, progression of dysautonomic manifestations, or a >20% worsening in nerve conduction compared with baseline measurements.18,22 In cases of ambiguity in classifying treatment response, the decision was made at the discretion of the treating physician.

Statistical analysisDescriptive statistics were used to summarise clinical and demographic variables. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations (SD) for normally distributed variables or as medians and quartiles 1 and 3 (Q1–Q3) for non-normally distributed variables. The Chi-square test was used to analyse categorical variables, and odds ratios (OR) were calculated as a measure of association. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify variables influencing treatment response and to control for possible confounders or effect modifiers. Robust methods were used to estimate confidence intervals. The multivariate logistic regression analysis included variables showing P-values<.1 in the univariate analysis, as well as other variables that could potentially influence the development of treatment response. Results were considered statistically significant at P-values<.05. Statistical analysis was performed using statistics software (R for Windows, version 4.3.1, and Wizard Pro for Mac, version 2.0.12).

ResultsDemographic data at treatment onsetA total of 53 patients with vATTR were included. Forty-four patients (83%) were treated with tafamidis and 23 patients (43%) were treated with patisiran. Fourteen patients (26%) were treated sequentially with both tafamidis and patisiran at different stages of their disease.

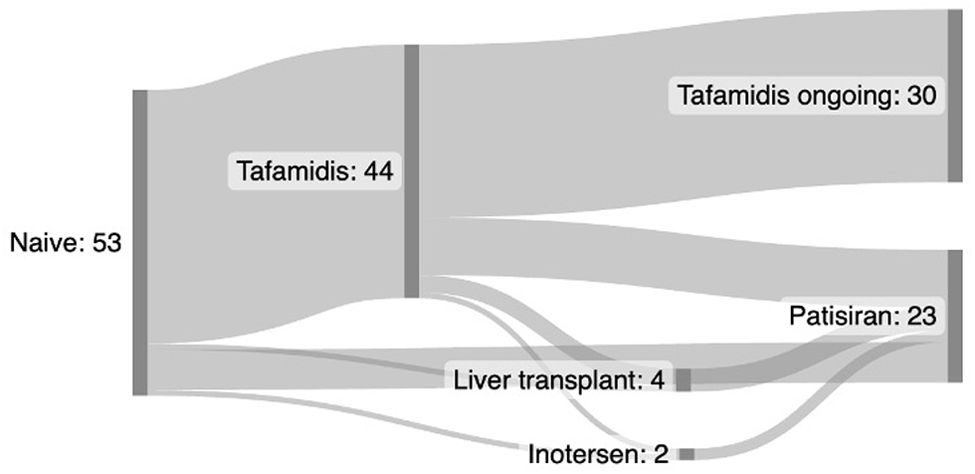

In the tafamidis arm, all patients were treatment-naive. However, of the 23 patients who received patisiran, only 7 (29%) were treatment-naive. Of the remainder, one patient had previously been treated with inotersen, one patient had undergone liver transplantation, and 14 patients had previously been treated with tafamidis. Of those previously treated with tafamidis, one had also been treated with inotersen, and 3 had undergone liver transplantation prior to starting treatment with patisiran (Fig. 1).

All patients were treated for at least 6 months. The mean treatment duration (SD) was 38.9 (27.47) months in the tafamidis group and 31.9 (18.5) months in the patisiran group.

The sex distribution of the patient cohort was relatively balanced, with 25 women (47%) and 28 men (53%). The mean age at disease onset was 61 years, with a range of 36 to 85 years, reflecting the broad age spectrum of patients with vATTR. The mean time from symptom onset to diagnosis was 18 months, although this also varied widely, from immediate diagnosis (0 months) to a delay of up to 72 months.

In terms of genetic profiles, the Val50Met mutation was the most frequent, detected in 24 patients (45%). This was followed by the Ser97Tyr mutation in 7 patients (13%), Ser43Asn and Glu109Lys in 6 patients each (11% each), and Val142Ile in 3 patients (6%). Other mutations were found in the remaining 7 cases (13%).

All patients treated with tafamidis were in Coutinho stage 1 at disease onset, in accordance with product specifications. In contrast, only 10 patients (43%) in the patisiran arm were in stage 1, while 13 patients (57%) were in stage 2, indicating higher disease severity in the patisiran-treated group. This is consistent with the higher PND stage, initial NIS, and scores on other scales in the patisiran arm.

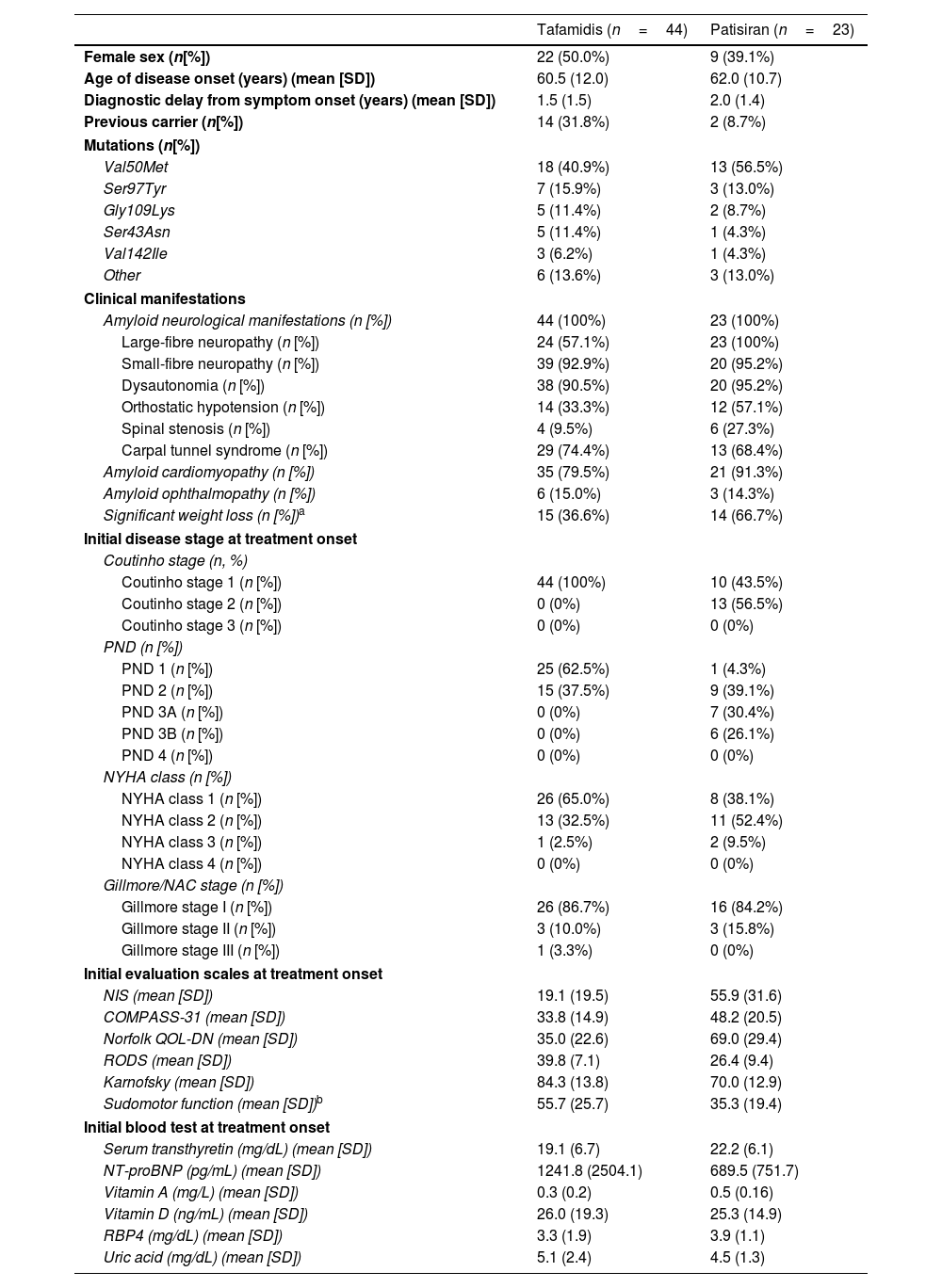

Table 1 presents the demographic, clinical, genetic, and laboratory characteristics, disease stage, and clinical scale scores at disease onset of patients treated with tafamidis and patisiran.

Demographic data and clinical manifestations at baseline.

| Tafamidis (n=44) | Patisiran (n=23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex (n[%]) | 22 (50.0%) | 9 (39.1%) |

| Age of disease onset (years) (mean [SD]) | 60.5 (12.0) | 62.0 (10.7) |

| Diagnostic delay from symptom onset (years) (mean [SD]) | 1.5 (1.5) | 2.0 (1.4) |

| Previous carrier (n[%]) | 14 (31.8%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Mutations (n[%]) | ||

| Val50Met | 18 (40.9%) | 13 (56.5%) |

| Ser97Tyr | 7 (15.9%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Gly109Lys | 5 (11.4%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Ser43Asn | 5 (11.4%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Val142Ile | 3 (6.2%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Other | 6 (13.6%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Clinical manifestations | ||

| Amyloid neurological manifestations (n [%]) | 44 (100%) | 23 (100%) |

| Large-fibre neuropathy (n [%]) | 24 (57.1%) | 23 (100%) |

| Small-fibre neuropathy (n [%]) | 39 (92.9%) | 20 (95.2%) |

| Dysautonomia (n [%]) | 38 (90.5%) | 20 (95.2%) |

| Orthostatic hypotension (n [%]) | 14 (33.3%) | 12 (57.1%) |

| Spinal stenosis (n [%]) | 4 (9.5%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome (n [%]) | 29 (74.4%) | 13 (68.4%) |

| Amyloid cardiomyopathy (n [%]) | 35 (79.5%) | 21 (91.3%) |

| Amyloid ophthalmopathy (n [%]) | 6 (15.0%) | 3 (14.3%) |

| Significant weight loss (n [%])a | 15 (36.6%) | 14 (66.7%) |

| Initial disease stage at treatment onset | ||

| Coutinho stage (n, %) | ||

| Coutinho stage 1 (n [%]) | 44 (100%) | 10 (43.5%) |

| Coutinho stage 2 (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 13 (56.5%) |

| Coutinho stage 3 (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| PND (n [%]) | ||

| PND 1 (n [%]) | 25 (62.5%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| PND 2 (n [%]) | 15 (37.5%) | 9 (39.1%) |

| PND 3A (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| PND 3B (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| PND 4 (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| NYHA class (n [%]) | ||

| NYHA class 1 (n [%]) | 26 (65.0%) | 8 (38.1%) |

| NYHA class 2 (n [%]) | 13 (32.5%) | 11 (52.4%) |

| NYHA class 3 (n [%]) | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (9.5%) |

| NYHA class 4 (n [%]) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gillmore/NAC stage (n [%]) | ||

| Gillmore stage I (n [%]) | 26 (86.7%) | 16 (84.2%) |

| Gillmore stage II (n [%]) | 3 (10.0%) | 3 (15.8%) |

| Gillmore stage III (n [%]) | 1 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Initial evaluation scales at treatment onset | ||

| NIS (mean [SD]) | 19.1 (19.5) | 55.9 (31.6) |

| COMPASS-31 (mean [SD]) | 33.8 (14.9) | 48.2 (20.5) |

| Norfolk QOL-DN (mean [SD]) | 35.0 (22.6) | 69.0 (29.4) |

| RODS (mean [SD]) | 39.8 (7.1) | 26.4 (9.4) |

| Karnofsky (mean [SD]) | 84.3 (13.8) | 70.0 (12.9) |

| Sudomotor function (mean [SD])b | 55.7 (25.7) | 35.3 (19.4) |

| Initial blood test at treatment onset | ||

| Serum transthyretin (mg/dL) (mean [SD]) | 19.1 (6.7) | 22.2 (6.1) |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) (mean [SD]) | 1241.8 (2504.1) | 689.5 (751.7) |

| Vitamin A (mg/L) (mean [SD]) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.5 (0.16) |

| Vitamin D (ng/mL) (mean [SD]) | 26.0 (19.3) | 25.3 (14.9) |

| RBP4 (mg/dL) (mean [SD]) | 3.3 (1.9) | 3.9 (1.1) |

| Uric acid (mg/dL) (mean [SD]) | 5.1 (2.4) | 4.5 (1.3) |

Average electrochemical skin conductance (ESC) in the feet, measured in microsiemens using a Sudoscan® device.

COMPASS-31: Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31; NAC: National Amyloidosis Centre; NIS: Neuropathy Impairment Score; Norfolk QOL-DN: Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy scale; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; NYHA: New York Heart Association Functional Classification; PND: Polyneuropathy Disability score; RBP4: retinol binding protein 4; RODS: Rasch-built Overall Disability Score; SD: standard deviation.

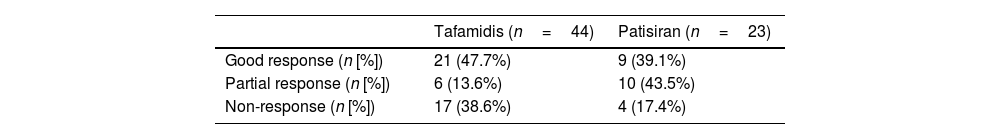

In terms of treatment response, 61.4% of patients receiving tafamidis and 82.6% of patients receiving patisiran showed a good or partial improvement at the last follow-up visit (Table 2). No significant differences in response to patisiran were observed between patients with and without prior exposure to tafamidis (P=.426).

At the last follow-up, 25 tafamidis-treated patients (56.8%) and 19 patisiran-treated patients (82.6%) were still on treatment. Thirty-two tafamidis-treated patients (72.7%) and only 2 patisiran-treated patients (8.7%) had switched treatment due to inadequate response. There were no significant differences in the duration of treatment with tafamidis (P=.747) or patisiran (P=.146) between the different response groups. There were no treatment switches due to drug-related adverse events. Regarding mortality, 5 patients (11.3%) in the tafamidis group and 2 patients (8.7%) in the patisiran group died. These deaths were not attributed to the drugs.

Plasma TTR levels increased by a mean of 33.0% (51.1%) in patients treated with tafamidis and decreased by 83.7% (6.8%) in patients treated with patisiran. Notably, the range of the reduction in patisiran level was between 66.7% and 90.4%.

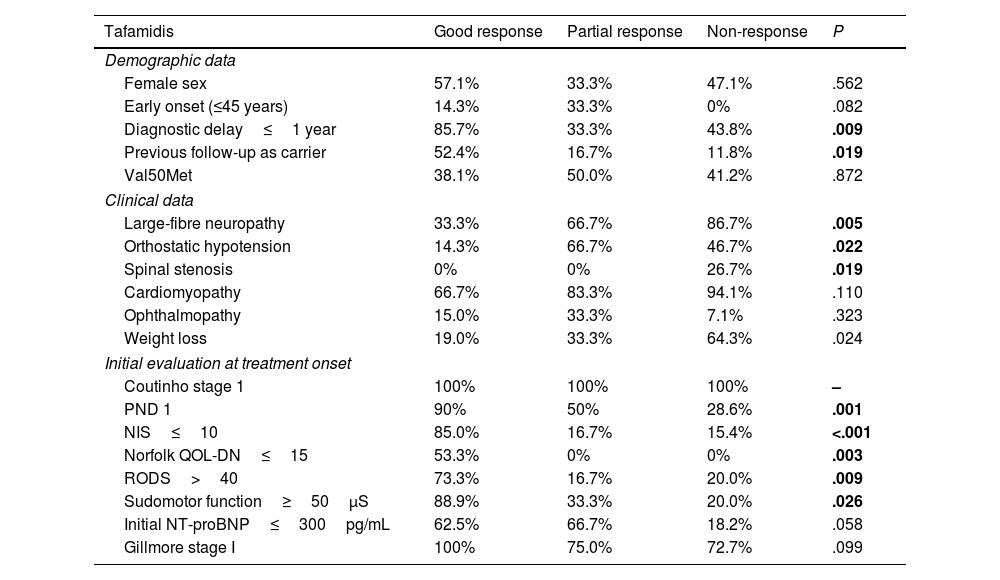

Predictors of treatment responseIn our analysis of predictors of treatment response in the tafamidis and patisiran treatment groups, patients were categorised as good responders, partial responders, and non-responders (Table 3). Significant differences were observed in the univariate analysis. We then calculated ORs for these significant results for each group (tafamidis and patisiran), based on the previous results.

Treatment responses in tafamidis and patisiran groups and pre-treatment variables.

| Tafamidis | Good response | Partial response | Non-response | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Female sex | 57.1% | 33.3% | 47.1% | .562 |

| Early onset (≤45 years) | 14.3% | 33.3% | 0% | .082 |

| Diagnostic delay≤1 year | 85.7% | 33.3% | 43.8% | .009 |

| Previous follow-up as carrier | 52.4% | 16.7% | 11.8% | .019 |

| Val50Met | 38.1% | 50.0% | 41.2% | .872 |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Large-fibre neuropathy | 33.3% | 66.7% | 86.7% | .005 |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 14.3% | 66.7% | 46.7% | .022 |

| Spinal stenosis | 0% | 0% | 26.7% | .019 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 66.7% | 83.3% | 94.1% | .110 |

| Ophthalmopathy | 15.0% | 33.3% | 7.1% | .323 |

| Weight loss | 19.0% | 33.3% | 64.3% | .024 |

| Initial evaluation at treatment onset | ||||

| Coutinho stage 1 | 100% | 100% | 100% | – |

| PND 1 | 90% | 50% | 28.6% | .001 |

| NIS≤10 | 85.0% | 16.7% | 15.4% | <.001 |

| Norfolk QOL-DN≤15 | 53.3% | 0% | 0% | .003 |

| RODS>40 | 73.3% | 16.7% | 20.0% | .009 |

| Sudomotor function≥50μS | 88.9% | 33.3% | 20.0% | .026 |

| Initial NT-proBNP≤300pg/mL | 62.5% | 66.7% | 18.2% | .058 |

| Gillmore stage I | 100% | 75.0% | 72.7% | .099 |

| Patisiran | Good response | Partial response | Non-response | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||

| Female sex | 22.2% | 50.0% | 50.0% | .412 |

| Early onset (≤45 years) | 22.2% | 0% | 0% | .204 |

| Diagnostic delay≤1 year | 66.7% | 33.3% | 50.0% | .368 |

| Previous carrier | 11.1% | 0% | 25.0% | .308 |

| Val50Met | 44.4% | 70.0% | 50.0% | .511 |

| Clinical data | ||||

| Large-fibre neuropathy | 100% | 100% | 100% | – |

| Orthostatic hypotension | 66.7% | 33.3% | 100% | .097 |

| Spinal stenosis | 22.2% | 33.3% | 25.0% | .864 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 88.9% | 100% | 75.0% | .308 |

| Ophthalmopathy | 11.1% | 11.1% | 33.3% | .595 |

| Weight loss | 66.7% | 66.7% | 66.7% | 1.000 |

| Initial evaluation at treatment onset | ||||

| Coutinho stage 1 | 77.8% | 20.0% | 25.0% | .029 |

| PND 1 | 11.1% | 0% | 0% | .443 |

| NIS≤40 | 66.7% | 20.0% | 0% | .028 |

| Norfolk QOL-DN≤15 | 100% | 100% | 75% | .229 |

| RODS>40 | 100% | 100% | 100% | .000 |

| Sudomotor function≥50μS | 25.0% | 33.3% | 100% | .325 |

| Initial NT-proBNP≤300pg/mL | 50.0% | 20.0% | 0% | .311 |

| Gillmore stage I | 100% | 90.0% | 0% | .002 |

NIS: Neuropathy Impairment Score; Norfolk QOL-DN: Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy scale; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide; PND: Polyneuropathy Disability score; RODS: Rasch-built Overall Disability Score.

For the tafamidis group, we identified several predictors of good response. These included diagnostic delay≤1 year (OR: 8.7; 95% CI, 2.0–38.4; P=.004), being a previous carrier (OR: 7.3; 95% CI, 1.7–32.3; P=.009), PND score of 1 (OR: 16.7; 95% CI, 3.0–93.9; P=.001), NIS score≤7 (OR: 19.8; 95% CI, 3.4–114.1; P<.001); Norfolk QOL-DN score≤15 (OR: 37.4; 95% CI, 1.9–736.3; P=.017), RODS score>40 (OR: 11.9; 95% CI, 2.2–65.1; P=.004), Karnofsky Performance Status Scale score≥90 (OR: 8.7; 95% CI, 1.2–61.7; P=.029), and mean foot sudomotor function≥50μS (OR: 24.0; 95% CI, 1.74–330.82; P=.018) before treatment.

Conversely, the predictors of non-response in the tafamidis group were PND score of 2 (OR: 10.5; 95% CI, 2.3–47.8; P=.002), large fibre involvement (OR: 9.4; 95% CI, 1.8–50.5; P=.009), significant weight loss (OR: 6.3; 95% CI, 1.5–26.1; P=.011), lumbar spinal stenosis (OR: 21.5; 95% CI, 1.1–433.0; P=.045), and NIS score>10 (OR: 12.4; 95% CI, 2.2–69.2; P=.004) at diagnosis.

In contrast, in the patisiran arm, the predictors of good response were a Coutinho stage of 1 (OR: 12.8; 95% CI, 1.7–97.2; P=.013) and NIS score≤40 (OR: 12.0; 95% CI, 1.6–92.3; P=.017) at disease onset. The only identified predictor of non-response was a Gillmore or NAC stage of II (OR: 55.0; 95% CI, 1.7–1760.6; P=.023). No patients with Gillmore stage III were included.

None of the other parameters studied showed significant differences between treatment response groups, for either drug.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of response to tafamidis and patisiran based on initial NIS showed significant results. For tafamidis, a good response was most likely for patients with initial NIS scores≤12.5. This finding was supported by high sensitivity (90%) and specificity (85%) with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.903 (Fig. 2A). In a similar analysis for patisiran, good response was predicted for initial NIS scores≤57. This cut-off score showed sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 71%, and an AUC of 0.817 (Fig. 2B).

DiscussionOur research focused on exploring potential predictors of therapeutic response to tafamidis and patisiran in patients diagnosed with vATTR.

Patients with vATTR showed a range of responses to both tafamidis and patisiran, similar to those described in the literature. The response in the patisiran group was good, even among patients with greater severity of neuropathy.

Predictors of good response to tafamidis included lower clinical severity (lower PND and NIS scores and better scores on other clinical scales) and better foot sudomotor function at disease onset. In our study, an initial NIS score below 7 was predictive of good response to tafamidis, whereas an NIS score above 10 was associated with non-response. This indicates that patients with minimal neurological impairment at baseline were most likely to benefit significantly from tafamidis. Other predictors of good response included shorter diagnostic delay and previous follow-up as an asymptomatic carrier, which is widely recognised to facilitate early diagnosis.

Predictors of non-response to tafamidis included greater clinical severity (higher PND and NIS scores, large-fibre neuropathy) and significant weight loss. The role of lumbar spinal stenosis as a predictor of poor response may be explained by the higher prevalence of this manifestation in patients with late onset and large-fibre neuropathy. However, further research is needed to better understand this aspect.

In the literature on factors predicting response to tafamidis, a notable study was conducted by Monteiro et al.18 in 2019, including 210 patients from an endemic area. They identified female sex, NIS score<10, lower Norfolk QOL-DN scores, and decreased plasma TTR and troponin T levels as positive predictors of tafamidis response. As mentioned above, our study found similar results regarding NIS as a predictive factor. On the other hand, we did not find a significant association with female sex. This discrepancy may be due to the smaller sample size in our study and the fact that our research was conducted in patients from a non-endemic area with a late-onset disease phenotype, which makes it unclear whether the predictive factors behave similarly in both groups of patients. We also found no statistical association between treatment response and initial plasma TTR levels or changes in these levels with treatment. This is consistent with recent publications showing that plasma TTR levels do not predict response to tafamidis treatment.23

Studies conducted in non-endemic areas and employing smaller sample sizes have indirectly analysed factors associated with response to tafamidis. These studies suggest an association between poorer response to tafamidis and later treatment onset,24 more severe neuropathy,24,25 and lower modified body mass index (mBMI).24–26 Our study is consistent with these findings, although we did not observe significant correlations with later age of disease onset or mutation type (Val50Met vs non-Val50Met), as reported in other studies.24

In the patisiran group, the main factor predicting a good response was also lower clinical severity, with lower Coutinho stage and NIS score at disease onset. Consequently, our findings suggest that early initiation of patisiran therapy is associated with a more favourable response, particularly when combined with a Coutinho stage of 1 and an NIS<40. This finding, combined with the fact that NIS>10 is associated with a poor response to tafamidis, highlights the importance of considering the use of patisiran earlier in the disease process.

These findings are consistent with recent publications showing that patients from the APOLLO trial with milder polyneuropathy and receiving early patisiran treatment maintained superior scores on several functional and quality of life scales compared to patients in the higher severity quartiles.27 On the other hand, other studies suggest that patisiran may be beneficial in the management of dysautonomic symptoms of neuropathy.28 Despite this, our study did not find significant differences in dysautonomia to be a determinant of treatment response. This may be influenced by the overwhelming prevalence of dysautonomic symptoms (95%) within the patisiran cohort, which inherently complicates statistical comparisons between groups. Given these findings, further investigation is warranted to further our understanding of dysautonomic manifestations. Similarly, we did not find a significant association between response to treatment with patisiran and the percentage reduction in TTR levels, probably because the reduction in TTR was greater than 70% in almost all patients. This suggests that a good biochemical response to patisiran is not always associated with a good clinical response.

The only identified predictor of non-response to patisiran was a Gillmore stage of II, although no association was found between cardiac involvement and neurological response to patisiran. Similarly, cardiac response to Patisiran was not analysed in this study. Therefore, further research is needed in this area to clarify the clinical significance of this finding.

A limitation of our study is that we did not evaluate the factors predicting response to other approved therapies for vATTR, such as inotersen. This is due to the limited number of patients receiving these therapies at our centre, which makes robust statistical analysis a challenge. We have not identified any literature specifically discussing predictors of response to inotersen.

In a study of real-life experience with inotersen, it was reported that some patients presented drug-induced hypotension, requiring dose reduction or regimen adjustment, and in some cases even leading to permanent discontinuation of treatment.29 Given this reported side effect, caution should be exercised when considering the use of this drug as a first-line treatment in patients with orthostatic hypotension. Further research in this area to identify factors predictive of response to inotersen would indeed be beneficial. In addition, future studies could use real-world data from other recently approved therapies, such as vutrisiran, to further improve our understanding.

Based on the above discussion, a shift in the therapeutic paradigm could be proposed. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach to vATTR treatment, our results suggest that predictive factors may guide the selection and application of treatments. This personalised approach could potentially prevent years of disease progression with ineffective treatments, allowing for earlier and more effective interventions, which in turn could improve patient outcomes.

For this reason, we propose a new treatment algorithm (Fig. 3), based on the treatment plan proposed by Adams et al.30 This algorithm incorporates the identified predictors of response to tafamidis and patisiran, which can be used to guide the selection of an initial treatment for these patients. This new therapeutic approach will provide a more personalised and evidence-based decision-making tool for initiating treatment in these patients.

Proposed vATTR treatment algorithm. Adapted from Adams et al.30 ESC: electrochemical skin conductance; FAP: familial amyloid polyneuropathy; HF: heart failure; NIS: Neuropathy Impairment Score; Norfolk QOL-DN: Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy scale; NYHA: New York Heart Association Functional Classification; PND: Polyneuropathy Disability score; RODS: Rasch-built Overall Disability Score; vATTR: hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis.

Regarding the limitations of this study, it should be noted that it follows a retrospective design, which by its nature can lead to potential data loss. In addition, although we evaluated cardiac parameters, we did not evaluate cardiac response. Therefore, these results need to be validated in subsequent studies.

Another major limitation is the sample size, although it is important to note that this is a substantial number of patients, considering the rarity of this disease in a non-endemic region. This limited sample size caused difficulties for certain statistical analyses, such as multivariate analysis. On the other hand, a major limitation is the overlap of patients between the tafamidis and patisiran treatment groups, as 14 patients received both tafamidis and patisiran at some point during their treatment, making it difficult to compare the 2 groups of patients.

Despite these limitations, our study has unique and valuable strengths. In particular, it is the first study to address predictors of response to patisiran and to examine factors predicting response to both tafamidis and patisiran. Furthermore, the results of this study allow us to propose a potential shift in the therapeutic paradigm, implying significant change and individualisation in the management of these patients (Fig. 3). This expanded focus provides a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic options available for the management of vATTR.

Our results highlight the importance of early diagnosis and treatment in vATTR and may help clinicians to design more individualised therapeutic strategies, thereby contributing to personalised vATTR management. However, the vATTR treatment landscape remains a significant clinical challenge due to the complex nature of the disease. Future studies should continue to focus on identifying and validating additional predictors of treatment response and optimising personalised treatment strategies for this complex disease. Despite these needs, our study represents an important step in the evolution of personalised vATTR management.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, this retrospective study evaluated treatment responses and identified predictors of response in patients with vATTR receiving either tafamidis or patisiran. Significant predictors of a good response to tafamidis included a shorter delay in diagnosis, lower disease severity scores, and better foot sudomotor function at baseline, while predictors of non-response included greater clinical severity and significant weight loss. In the patisiran group, the main predictor of good response was also lower clinical severity at baseline.

Our results suggest that initial NIS is a useful predictor of response to both tafamidis and patisiran. These results help to better tailor treatment decisions for individual patients based on their initial NIS.

Based on these findings, we propose a new therapeutic approach in which predictive factors may guide the selection and use of treatments. This personalised treatment strategy could potentially prevent years of disease progression with ineffective treatments. Future studies should continue to focus on identifying and validating additional predictors of treatment response, individualising treatment strategies, and promoting further research to optimise patient care in this complex and multifaceted disease.

Statement of ethics and consentThis study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee. All the authors have read the instructions to the authors, and all accept the conditions posed.

Submission declarationAll authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript prior to its submission.

FundingThe authors declare that this study was not funded.

Conflict of interestIn the interest of full transparency, it should be noted that some authors have had temporary affiliations with certain pharmaceutical companies at some point, including Pfizer, Alnylam, Akcea, Lupin Neuroscience, SOBI, Astra-Zeneca, Eidos, NovoNordisk, and Proclara. These affiliations have not influenced the content or conclusions of this article.

Data availability statementData available on request.

We would like to thank the patients who participated in this study. Without their participation, this study would not have been possible.