Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt amyloidosis) has traditionally been considered a purely cardiological condition. However, recent studies suggest that neurological involvement in ATTRwt amyloidosis is more significant than previously believed. We conducted a comprehensive neurological study aiming to contribute to a better clinical and functional characterization of the neuropathy in this disease.

Patients and methodsFourteen patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis were recruited at Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain). Participants completed various clinical questionnaires and underwent neurological examination, functional tests, and measurement of electrochemical skin conductance. Additionally, their laboratory analysis results and electrophysiological data were reviewed.

ResultsThe cohort included 14 men with an average age of 83.07 years (standard deviation: 6.39). Overall, 92.9% presented objective signs of neuropathy, with 71.4% showing electrophysiological evidence of neuropathy, which was predominantly axonal and sensorimotor. Patients scored a median of 8 (interquartile range: 8) on the Neuropathy Impairment Score, and 1 on the Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy and Polyneuropathy Disability stages. Electrochemical skin conductance was altered in 64.3%, although there was limited impact on the Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31 (median: 12) and Survey of Autonomic Symptoms (median: 7.5) scales. A decrease in quality of life, according to the Norfolk scale, was reported by 69.2% of patients.

ConclusionsLarge- and small-fiber neuropathy are highly prevalent in ATTRwt amyloidosis. Although their clinical and functional impact is mild to moderate, they reduce the patients’ quality of life. This finding sheds light on the disease and paves the way for new therapeutic alternatives.

La amiloidosis por transtirretina esporádica (amiloidosis ATTRwt) se ha considerado tradicionalmente como una condición puramente cardiológica. Sin embargo, estudios recientes sugieren que la afectación neurológica en la amiloidosis ATTRwt es más significativa de lo que se creía anteriormente. Realizamos un estudio neurológico integral con el objetivo de contribuir a una mejor caracterización clínica y funcional de la neuropatía en esta enfermedad.

Pacientes y métodosSe reclutaron 14 pacientes con amiloidosis ATTRwt en el Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid. Los participantes completaron varios cuestionarios clínicos y se sometieron a evaluaciones neurológicas, pruebas funcionales y medición de la conductancia electroquímica de la piel. Además, se revisaron sus resultados de laboratorio y datos electrofisiológicos.

ResultadosLa cohorte incluyó 14 varones con una edad media de 83,07 años (DE 6,39). En general, el 92,9% presentó signos objetivos de neuropatía. El 71,4% tenía evidencia electrofisiológica de neuropatía, predominantemente axonal y sensoriomotora. La puntuación mediana fue de 8 (RIC 8) en la escala Neuropathy Impairment Score (NIS) y de 1 en las clasificaciones Familial Amyloyd Polyneuropathy (FAP) y Polyneuropathy Disability (PND). La conductancia electroquímica de la piel estaba alterada en el 64,3%, aunque con un impacto limitado en las escalas COMPASS-31 (mediana 12) y Survey of Autonomic Symptoms (SAS) (mediana 7,5). Una disminución en la calidad de vida, según la escala de Norfolk, fue reportada por el 69,2% de los pacientes.

ConclusionesLa neuropatía de fibra gruesa y fina es altamente prevalente en la amiloidosis ATTRwt. Aunque su impacto clínico y funcional es de leve a moderado, reduce la calidad de vida de los pacientes. Este hallazgo arroja luz sobre la enfermedad y abre el camino para nuevas alternativas terapéuticas.

Wild-type transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTRwt amyloidosis) is a systemic disorder characterized by the disassembly of transthyretin (TTR) tetramers into misfolding monomers that aggregate and form amyloid fibrils.1 These deposits can accumulate in various organs, leading to damage to the nervous, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal systems.2–7 Unlike its hereditary counterpart, hereditary TTR amyloidosis (ATTRv), ATTRwt amyloidosis is not caused by mutations that destabilize TTR. Instead, a number of factors including advanced age have been linked to this condition4; the role of other potential contributing elements, such as certain amyloid-associated genes, is still being researched.8 The precise prevalence of ATTRwt amyloidosis remains unknown. However, in series of autopsies, infiltration of the myocardium by TTR has been found in up to 25% of patients over 80 years of age,9 and studies with cardiac scintigraphy have shown prevalence rates of 4% in men and 1% in women over 75 years of age,10 with even higher rates in those with specific cardiac conditions.11

Historically, ATTRwt amyloidosis was primarily considered a cardiac disease, bearing similarities to certain types of late-onset or cardiac-mutation ATTRv, but with less significant neurological involvement than the classical, early-onset Val50Met ATTRv variant.12–16 In the last decade, however, numerous studies have highlighted a higher prevalence of neuropathic symptoms in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis than previously recognized. ATTRwt is also frequently associated with musculoskeletal disorders, due to amyloid deposits in connective tissues. This results in common conditions like carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), lumbar spinal stenosis, and spontaneous rupture of the biceps tendon.17–26

Currently, several disease-modifying treatments are available for patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis. Tafamidis, indicated for ATTRv with mild neuropathy and for cardiopathy in both ATTRv and ATTRwt amyloidosis, is one of the most utilized therapies.6,27–29 Gene silencing therapies like patisiran, vutrisiran, and inotersen, approved solely for early-stage neuropathy in ATTRv, represent other therapeutic options.6,11,30

Recent research efforts have focused on characterizing the neuropathic aspect of ATTRwt amyloidosis through objective methods such as nerve conduction studies (NCS) and electrochemical skin conductance (ESC) tests,22,23,26 revealing a significant proportion of patients with a predominantly axonal and sensory or sensorimotor neuropathy.17,19,20,24 However, in most of these studies, neurological evaluation is limited. This is compounded by the high frequency of age-related comorbidities present in these patients, which can act as confounding factors when assessing peripheral neuropathy in ATTRwt amyloidosis. Therefore, a detailed understanding of the neurological manifestations of ATTRwt amyloidosis is crucial for improving symptomatic treatment and possibly guiding future treatment directions.20

The objective of this study is to better understand the neuropathy in ATTRwt amyloidosis, including its prevalence, neurophysiological characteristics, and clinical and functional impact. With this aim, we conducted an extensive observational study which involved comprehensive work-up of a cohort of 14 patients from the Hospital Clínico San Carlos (HCSC) in Madrid, Spain. Our research encompassed a variety of metrics, including performance status and clinical scores, neurological examination, cognitive assessment, nerve conduction studies, and electrochemical skin conductance tests.

Materials and methodsPatients and selection criteriaWe recruited 14 consecutive patients diagnosed with ATTRwt amyloidosis, all of whom were under the care of the neuromuscular unit of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain). This unit serves patients from central Spain and collaborates with various hospital departments as part of the multidisciplinary amyloidosis team. The diagnosis of ATTRwt amyloidosis was confirmed using the following criteria:

- (1)

Findings in heart ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging consistent with cardiac amyloidosis, along with increased uptake (Perugini grade 2 or 3) in [99Tc]Tc-diphosphono-propanodicarboxylic acid, [99Tc]Tc-pyrophosphate, or [99Tc]Tc-hydroxymethylene diphosphonate scintigraphy;

- (2)

Absence of monoclonal protein in serum and urine;

- (3)

Negative genetic test results for TTR gene mutations using the conventional Sanger sequencing method on a peripheral blood sample.

In addition, the following inclusion criteria were applied:

- (4)

Ability to understand and to voluntarily sign the informed consent form;

- (5)

Age ≥18 years;

- (6)

Being under follow-up by the neuromuscular unit, or by the internal medicine or the cardiology departments.

We also established the following exclusion criteria:

- (1)

Known moderate or severe cognitive impairment as per the patient's clinical record;

- (2)

Severe dependency that could impair the examination or the tests required for the study;

- (3)

Absence of a previous NCS after the diagnosis of ATTRwt amyloidosis.

After confirming that they met the aforementioned criteria, patients signed consent forms and were included in the cohort between April 2022 and February 2023. We retrospectively collected relevant information from their clinical records and arranged follow-up consultations for additional data.

Study designWe conducted a descriptive, cross-sectional study, gathering the following clinical and demographic data from our patients: age, sex, symptoms and their onset, weight, height, and comorbidities. Some of their data (disease history, comorbidities, NCS data) were retrospectively gathered from their clinical records. These patients were classified according to the Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy (FAP) scale and the Polyneuropathy Disability (PND) score for assessing the impact of polyneuropathy on gait, as well as the New York Heart Association (NYHA) score, which evaluates the functional stage related to heart failure. Laboratory tests were reviewed to classify patients according to the Gillmore staging system (UK National Amyloidosis Center [NAC] score).13 To determine our patients’ performance status, we used the Barthel index and Karnofsky Performance Status score, as well as the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT, measuring gait speed over a 10-m distance) and the Timed Up and Go test (TUG, assessing the ability to stand up, walk, and sit down). Additionally, the Fototest was applied as a screening tool for cognitive impairment.

Our patients underwent a neurological examination to determine their Neuropathy Impairment Score (NIS), which quantifies neuropathy severity on a scale from 0 to 244, and has been widely used in studies into ATTR.19 Physical examination included hand-grip dynamometry (measuring upper limb distal musculature strength) and blood pressure measurements in a supine position and at the first and third minutes after standing (to detect orthostatic intolerance).

Our patients also completed the following clinical questionnaires: the Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale (RODS, which grades functional and social independence in neuropathy patients from 0 to 48),31 the Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy scale (assessing quality of life from −2 to 136, with higher scores indicating poorer quality of life),32 and two scales that measure autonomic dysregulation, the Survey of Autonomic Symptoms (SAS, which includes 12 symptoms and grades their severity from 0 to 60)33 and the Composite Autonomic Symptom Score-31 (COMPASS-31, evaluating six symptomatic domains on a scale from 0 to 100).19

We also added objective data gathered from several tests. We reviewed patients’ NCS results to detect neuropathy and determine its nature (axonal and/or demyelinating, motor and/or sensory) in both upper and lower limbs, and to identify the presence and severity of CTS. For the NCS, which was always performed by the same specialist, monopolar needle electrodes and surface electrodes were used, and orthodromic motor and sensory conductions were performed in the upper limbs, as well as antidromic conductions in the lower limbs. For the electromyography, 26G concentric needle electrodes were used, placed in the largest muscle volume detected after voluntary activation by the patient, for each of the muscles examined. The reference values used were from the in-house population of the study center, Hospital Clínico San Carlos.

Some patients underwent further electrophysiological evaluation, including sympathetic skin response (SSR) and RR interval variability assessment, seeking objective signs of autonomic neuropathy. The reference values for these tests are shown in Table 1.34

Reference values for R–R interval variability.

| Patients | Controls | |

|---|---|---|

| R–R interval variability at rest (R%) | 15.7 (6.2) | 18.6 (5.9) |

| During deep breathing (D%) | 21.8 (8.1) | 31.4 (7.7) |

| Difference between D% and R% | 6.1 (7.0) | 12.7 (7.7) |

| Ratio D%/R% | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.8) |

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation).

We also measured ESC in the hands (hESC) and feet (fESC) of all patients using Sudoscan®, a method for assessing autonomic dysfunction related to small-fiber neuropathy.

StatisticsStatistical analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS software (version 21). Descriptive analysis is presented as means with standard deviation (SD) or as medians with interquartile range (IQR) for quantitative variables, and as frequency distribution for categorical variables. For hypothesis testing, the Fisher test was used for qualitative variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for comparing dichotomous qualitative variables with quantitative variables.

Ethical approvalThis study is compliant with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki from the World Medical Association (1964) and was approved by the Hospital Clínico San Carlos research ethics committee (internal code: 22/439-E). The authors followed local protocols for accessing patient information with a strictly scientific purpose, in accordance with the data protection regulations (Spanish Law 41/2002 of 14 November).

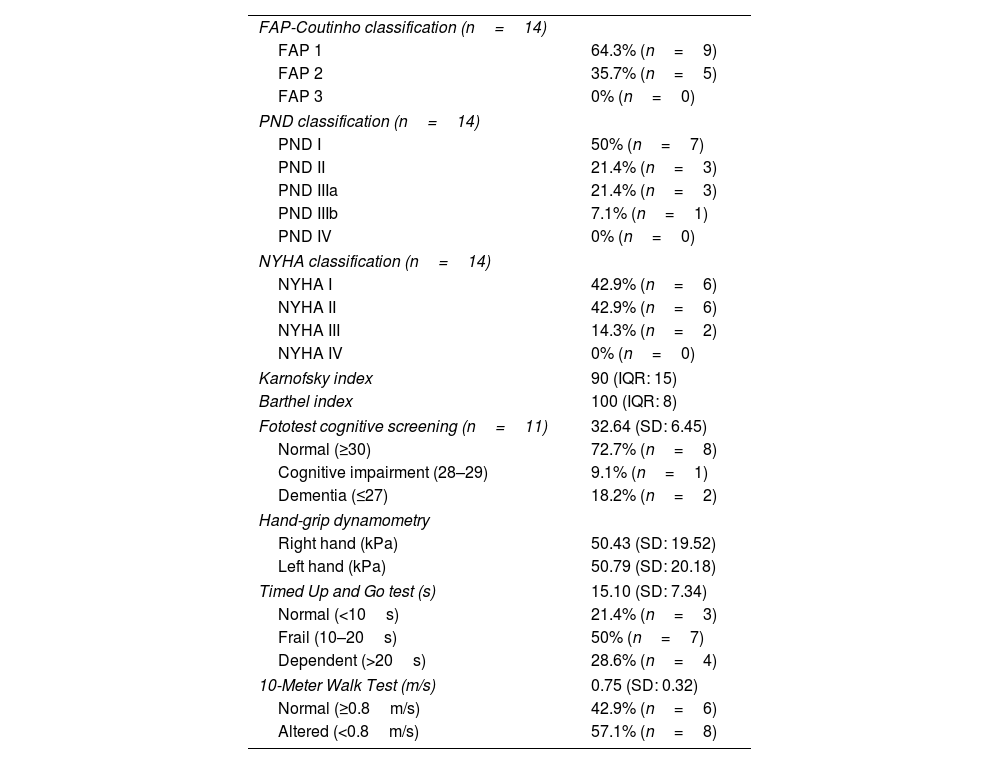

ResultsDemographic and functional dataA cohort of 14 patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis was included in the study, all of whom were men, with an average age of 83.07 years (SD: 6.39; range, 73–91). Twelve patients (85.8%) had no or mild-to-moderate dyspnea (NYHA I or II), and none had dyspnea at rest (NYHA IV). Seven patients (50%) were in stage 1 of the NAC score, which entails the best prognosis in this scoring system.13 Nine (64.3%) were classified as stage 1 in the FAP classification and 7 (50%) as stage 1 in the PND classification (Table 2).19

In this group, the median Barthel index score was 100, with 11 patients (78.6%) scoring ≥95, and the median Karnofsky Performance Status score was 90, with scores ≥90 points in 10 subjects (71.4%). Hand dynamometry testing revealed a mean grip strength of 50.43kPa (19.52) in the right limb and 50.79kPa (20.18) in the left. The mean time taken to complete the TUG test was 15.10s (7.34), with 50% (7 patients) taking 10–20s, and 28.6% (4 patients) taking longer than 20s. The mean walking speed in the 10MWT was 0.75m/s (0.32), with 57.1% (8 patients) walking at a speed <0.8m/s. The Fototest cognitive screening was applied to 11 participants. The mean score was 32.64 points, considered a normal value. However, 2 patients (18.2%) scored ≤27, suggestive of dementia, and one (9.1%) scored 29, suggestive of cognitive impairment (Table 3).35

Functional characteristics.

| FAP-Coutinho classification (n=14) | |

| FAP 1 | 64.3% (n=9) |

| FAP 2 | 35.7% (n=5) |

| FAP 3 | 0% (n=0) |

| PND classification (n=14) | |

| PND I | 50% (n=7) |

| PND II | 21.4% (n=3) |

| PND IIIa | 21.4% (n=3) |

| PND IIIb | 7.1% (n=1) |

| PND IV | 0% (n=0) |

| NYHA classification (n=14) | |

| NYHA I | 42.9% (n=6) |

| NYHA II | 42.9% (n=6) |

| NYHA III | 14.3% (n=2) |

| NYHA IV | 0% (n=0) |

| Karnofsky index | 90 (IQR: 15) |

| Barthel index | 100 (IQR: 8) |

| Fototest cognitive screening (n=11) | 32.64 (SD: 6.45) |

| Normal (≥30) | 72.7% (n=8) |

| Cognitive impairment (28–29) | 9.1% (n=1) |

| Dementia (≤27) | 18.2% (n=2) |

| Hand-grip dynamometry | |

| Right hand (kPa) | 50.43 (SD: 19.52) |

| Left hand (kPa) | 50.79 (SD: 20.18) |

| Timed Up and Go test (s) | 15.10 (SD: 7.34) |

| Normal (<10s) | 21.4% (n=3) |

| Frail (10–20s) | 50% (n=7) |

| Dependent (>20s) | 28.6% (n=4) |

| 10-Meter Walk Test (m/s) | 0.75 (SD: 0.32) |

| Normal (≥0.8m/s) | 42.9% (n=6) |

| Altered (<0.8m/s) | 57.1% (n=8) |

FAP: Familial Amyloid Polyneuropathy scale; NYHA: New York Heart Association; PND: Polyneuropathy Disability score.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation [SD]), median (interquartile range [IQR]), or as frequency distribution (absolute values in parentheses).

The comorbidities in these patients, according to their clinical records, included diabetes mellitus in 50% (n=7) and prediabetes in 7.1% (n=1). In addition, 2 individuals (14.3%) had vitamin B12 deficiency concomitantly with diabetes mellitus. Nevertheless, none of the participants showed thyroid disorders, monoclonal gammopathy, nor history of use of chemotherapeutic agents.

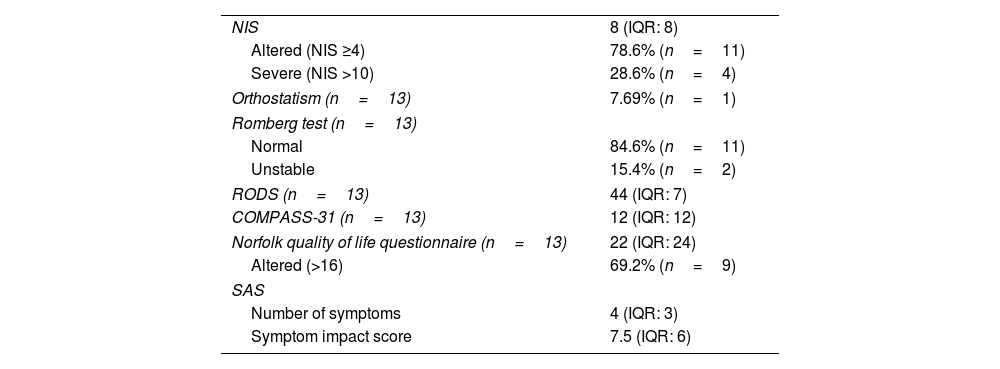

Clinical neurological resultsEleven patients (78.6%) presented an altered NIS (≥4), with a median of 8 points (IQR: 8; range, 2–30). Only 4 patients (28.6%) had an NIS >10, which is considered severe.19 On the Norfolk quality of life scale, the cohort scored a median of 22 points (24).32 On the other hand, the median RODS score was 44 points (17).31

Orthostatic hypotension, defined as a reduction in systolic pressure ≥20mmHg or diastolic pressure ≥10mmHg within the first 3min after standing from a supine position, was only observed in one participant (7.69%). The COMPASS-31 dysautonomia scale yielded a median of 12 points (12). In the SAS questionnaire, a median of 4 symptoms (3) was reported, with a median impact score of 7.5 (6). These results are summarized in Table 4.

Clinical neurological results.

| NIS | 8 (IQR: 8) |

| Altered (NIS ≥4) | 78.6% (n=11) |

| Severe (NIS >10) | 28.6% (n=4) |

| Orthostatism (n=13) | 7.69% (n=1) |

| Romberg test (n=13) | |

| Normal | 84.6% (n=11) |

| Unstable | 15.4% (n=2) |

| RODS (n=13) | 44 (IQR: 7) |

| COMPASS-31 (n=13) | 12 (IQR: 12) |

| Norfolk quality of life questionnaire (n=13) | 22 (IQR: 24) |

| Altered (>16) | 69.2% (n=9) |

| SAS | |

| Number of symptoms | 4 (IQR: 3) |

| Symptom impact score | 7.5 (IQR: 6) |

COMPASS-31: Composite Autonomic Symptom Score; NIS: Neuropathy Impairment Score; RODS: Rasch-built Overall Disability Scale; SAS: Survey of Autonomic Symptoms.

Data are shown as median (interquartile range [IQR]), or as frequency distribution (absolute values in parentheses).

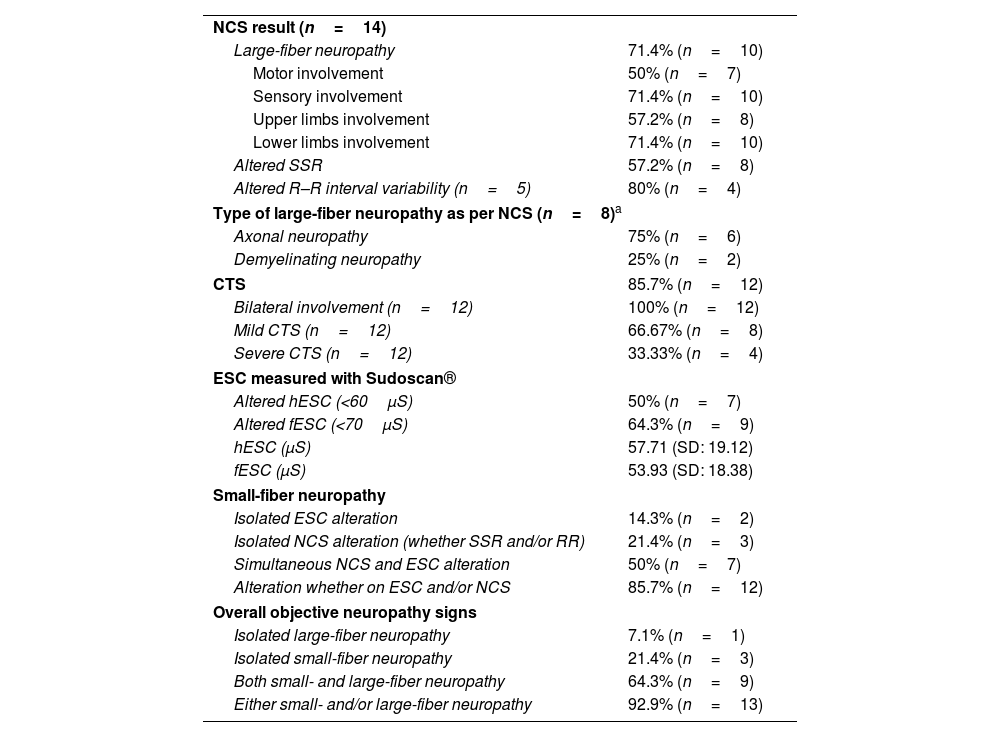

Ten patients (71.4%) had signs of large-fiber neuropathy in the NCS. Among these individuals, 100% had lower limb involvement, whereas only 80% (8 patients) had upper limb involvement. Furthermore, all patients showed sensory involvement, while 70% (7 patients) also presented motor involvement. In total, 50% of the cohort (7 patients) suffered from sensorimotor neuropathy, and 21.4% (3 patients) had pure sensory neuropathy. The nature of the neuropathy was reported in 8 of these 10 patients: involvement was axonal in 75% (6 patients) and demyelinating in 25% (2 patients).

In addition, 57.2% (8 patients) showed an abnormal SSR. RR interval variability was also studied in 5 patients, with abnormal results in 80% (4 patients).

Finally, 85.7% (n=12) of the participants presented electroneurographic data indicating CTS, which was bilateral in all cases. Involvement was mild in 66.67% (n=8) and severe in 33.33% (n=4) of these patients.

Electrochemical skin conductance resultsThe ESC, assessed with Sudoscan®, was considered pathological for values <70μS in the feet (fESC) and <60μS in the hands (hESC).26 The mean fESC recorded was 53.93μS (18.38), with 9 patients (64.3%) showing abnormalities. Meanwhile, the mean hESC was 57.71μS (19.12), with 50% (7 patients) displaying alterations.

Combined NCS and ESC resultsOverall, when combining data from NCS and ESC, we found that 85.7% (12/14 patients) had objective evidence of small-fiber neuropathy. Specifically, 50% (7 patients) showed signs of small-fiber neuropathy in both tests. Additionally, 21.4% (3 patients) presented normal ESC results but had abnormalities in NCS, either in SSR or RR. On the other hand, 14.3% (2 patients) had abnormal ESC findings without any dysautonomia indicators in NCS (Fig. 1).

When comparing these data with NCS results for sensory and motor neuropathy, 64.3% (9 patients) exhibited both large- and small-fiber neuropathy. Three patients (21.4%) had evidence of small-fiber neuropathy only, while one (7.1%) had only large-fiber neuropathy.

In summary, 92.9% of patients (n=13) presented objective data of neuropathy, whether small- or large-fiber, and only one (7.1%) was free of neuropathic involvement in the NCS and ESC studies (Fig. 2).

The summary of these results, obtained from electrophysiological examination and skin conductance tests, is displayed in Table 5.

Nerve conduction study and electrochemical skin conductance test results.

| NCS result (n=14) | |

| Large-fiber neuropathy | 71.4% (n=10) |

| Motor involvement | 50% (n=7) |

| Sensory involvement | 71.4% (n=10) |

| Upper limbs involvement | 57.2% (n=8) |

| Lower limbs involvement | 71.4% (n=10) |

| Altered SSR | 57.2% (n=8) |

| Altered R–R interval variability (n=5) | 80% (n=4) |

| Type of large-fiber neuropathy as per NCS (n=8)a | |

| Axonal neuropathy | 75% (n=6) |

| Demyelinating neuropathy | 25% (n=2) |

| CTS | 85.7% (n=12) |

| Bilateral involvement (n=12) | 100% (n=12) |

| Mild CTS (n=12) | 66.67% (n=8) |

| Severe CTS (n=12) | 33.33% (n=4) |

| ESC measured with Sudoscan® | |

| Altered hESC (<60μS) | 50% (n=7) |

| Altered fESC (<70μS) | 64.3% (n=9) |

| hESC (μS) | 57.71 (SD: 19.12) |

| fESC (μS) | 53.93 (SD: 18.38) |

| Small-fiber neuropathy | |

| Isolated ESC alteration | 14.3% (n=2) |

| Isolated NCS alteration (whether SSR and/or RR) | 21.4% (n=3) |

| Simultaneous NCS and ESC alteration | 50% (n=7) |

| Alteration whether on ESC and/or NCS | 85.7% (n=12) |

| Overall objective neuropathy signs | |

| Isolated large-fiber neuropathy | 7.1% (n=1) |

| Isolated small-fiber neuropathy | 21.4% (n=3) |

| Both small- and large-fiber neuropathy | 64.3% (n=9) |

| Either small- and/or large-fiber neuropathy | 92.9% (n=13) |

ESC: electrochemical skin conductance; hESC: hand ESC; fESC: foot ESC; NCS: nerve conduction study; RR: R–R interval variability; SSR: sympathetic skin response.

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation [SD]), or as frequency distribution (absolute values in parentheses).

ATTRwt amyloidosis was predominantly regarded as a cardiac disease until recent years, when studies began to explore its neurological component in depth. In this regard, our study was designed to better characterize the clinical and functional aspects of neuropathy in ATTRwt amyloidosis.

In our study, 92.9% of patients showed objective evidence of neuropathy in NCS and/or ESC assessments, involving either small or large fibers. This result exceeds those reported in previously published studies we reviewed, which found a rather broad range of prevalence rates for neuropathy signs and/or symptoms across different cohorts of ATTRwt amyloidosis (from 28%, as described in the original Transthyretin Amyloidosis Outcomes Survey [THAOS] report,18 to recent, more comprehensive studies demonstrating higher frequencies of sensorimotor axonal neuropathy at 83%21). The THAOS was among the earliest attempts to aggregate a substantial number of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis. This registry reports sensory neuropathy in 28.4% of these patients.18 The study by Yungher et al.,21 reporting a cohort of 151 patients with ATTRwt cardiomyopathy, found that 30.5% exhibited symptoms of neuropathy, with frequent comorbidities also observed. In this study, an additional retrospective analysis of neurophysiological studies was conducted in 12 patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis, which identified sensorimotor axonal neuropathy in 83%. A large percentage of patients also suffered from lumbar and cervical radiculopathies and ulnar neuropathy.21 A small study conducted in 2019 by Živković et al.17 analyzed the neurophysiological data of 5 patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis and polyneuropathy, finding a length-dependent sensorimotor axonal neuropathy, with mild symptoms and rarely associated with pain, weakness or dysautonomia. Another retrospective case–control analysis of 41 patients conducted by Russell et al.20 in 2020 found that 51% of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis presented with sensory or sensorimotor large-fiber neuropathy, which was mild in most cases. The frequency of neuropathy was significantly higher than that observed in the control group, even excluding other common causes of neuropathy. This study reports the association between neuropathy and more advanced stages of heart failure (NYHA II–IV), as well as a higher prevalence of CTS, ulnar neuropathy, vertebral stenosis, and radiculopathy among patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis.20 One of the most comprehensive studies to date is the recent work by Kleefeld et al.,19 published in 2022. This prospective analysis included 50 patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis, in whom analytical, cardiological, scintigraphic, neurological (including NIS, PND, and FAP scales), and neurophysiological studies were performed, in addition to evaluation of dysautonomia with the COMPASS-31, application of the Norfolk scale, and the tilt-table test in a subgroup of patients. In this cohort, 75% of patients presented neuropathy, which was mostly axonal, symmetrical, and length-dependent, generally of mild-to-moderate severity, without severe motor involvement. These patients presented little autonomic involvement, and only 8% required assistance for walking (FAP stage II).19

Regarding electrophysiological results exclusively, our data indicate that large-fiber sensory neuropathy is the predominant alteration (71.4%), frequently coexisting with a motor component (50%). The nature of this neuropathy is axonal in most patients, although it can be demyelinating in 25% of cases. These data support results from other works using NCS: individuals with ATTRwt amyloidosis typically present with axonal polyneuropathy, which is either sensory or sensorimotor.17,19–23 The aforementioned studies report objective electrophysiological signs of neuropathy in 52%20 to 83.3.%21 of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis, prevalences that are notably higher than those expected in the adult population (5%–8%).19 Our data are consistent with this, with NIS being altered (≥4) in 78.6% of our group, generally in the mild to moderate range, though 28.6% presented NIS indicating severe neuropathy (>10).19 These proportions are similar to those published in recent studies.19,22 In spite of this, scores on the RODS were fairly high (median of 44/48), indicating a high level of independence for daily living activities. Concurrently, the Barthel index (median of 100) and Karnofsky Performance Status score (median of 90) reveal a generally good functional status. The impact on walking in these patients is mild to moderate, with all subjects being able to walk independently or with some support. As in other cohorts, stage 1 predominates in the PND and FAP scales.17,19 These data suggest that, overall, functional capacity is preserved in most patients. However, TUG and 10MWT results fall within the frailty range for more than half of our patients, although these results could be related to their ages. Additionally, 69.2% of participants reported a notable impact (>16) on their quality of life according to the Norfolk scale. As suggested in previous studies,19 the median score is higher than that observed in diabetes and, for some patients, even at the level of those suffering from diabetic neuropathy.32 Notably, the 3 patients in our cohort with unaltered NIS (<4) are the only ones simultaneously in stage 1 of all 3 functional classifications (PND, FAP, and NYHA), and also the only ones with optimal results (<10s) in the TUG test. This suggests that these tests could be suitable for assessing functional status in ATTRwt amyloidosis. Moreover, 2 of these patients are among the only 4 participants in whom NCS did not detect neuropathy.

CTS was a very frequent finding in our cohort. This disorder associated with ATTRwt amyloidosis, whose prevalence rate is estimated at 50% by some authors,11 seems to be even more common among our patients. Studies focusing on neuropathic involvement in ATTRwt amyloidosis report prevalence rates exceeding 80%,20–22,26 which are consistent with our data. A study by Russell et al.20 in 2020 showed that both CTS and neuropathy were significantly more frequent in ATTRwt amyloidosis than in an age-matched group of healthy controls.

However, neuropathy associated with ATTRwt amyloidosis does not exclusively involve large fibers. These patients also suffer from different degrees of small-fiber neuropathy, as the literature has shown. However, the prevalence of autonomic neuropathy among patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis varies significantly across different studies, depending on its definition and the measures used to determine its presence. In 2013, the aforementioned THAOS study began, including a prospective cohort of 67 patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis, which has been growing since.18 Subsequent publications based on this cohort, such as the 2022 report (which describes symptomatic autonomic dysfunction in 7.6% of patients), indicate that the most frequent autonomic symptom is orthostatic hypotension24,25; interestingly, this symptom was only observed in one patient (7.1%) in our cohort. The latest update (2024), published 15 years after the beginning of the study, reports a prevalence of 15.9% for autonomic neuropathy, similar to that of sensory neuropathy (14.3%) and notably higher than the prevalence of motor neuropathy (2.8%).36 In contrast, the work of Papagianni et al.,23 which included clinical evaluation and NCS, reported higher prevalence of small-fiber neuropathy, in 78% of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis.

In our cohort, NCS detected an abnormal SSR in 57.2% of patients. Similarly, Sudoscan® found alterations in hESC in 50% and fESC in 64.3% of our participants, similar percentages to those indicated by other authors.22 The mean ESC measurements were below reference values, and even lower than those published by Kharoubi et al.26 in a large study in which Sudoscan® was used with 62 patients, and which also shows an association between fESC and cardiac prognosis. Clinically, our cohort reported a median of 4 autonomic symptoms on the SAS, with a modest impact (median 7.5/60) on quality of life. The median score on the COMPASS-31 scale was 12 (below the cut-off point of 30–32), similar to scores reported in other studies.19 These data suggest that while the prevalence of dysautonomia may be significant in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis when assessed using specific tests, such as Sudoscan® and neurophysiological studies, the frequency of debilitating dysautonomic symptoms remains low. Indeed, the 2022 THAOS report analyzed 158 ATTRwt patients with and without dysautonomia, detecting few differences between subgroups in the Norfolk quality of life questionnaire.24

Analyzing our results as a whole, it is evident that patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis can have both large- and small-fiber neuropathy, either in isolation or simultaneously. The majority (64.3%) present involvement of both types of fiber, but, notably, 3 patients (21.4%) presented exclusively small-fiber involvement, while a single participant (7.1%) had isolated large-fiber alteration. Remarkably, a total of 92.9% of patients presented objective signs of neuropathy, meaning that only one patient (7.1%) lacked such signs. These findings do not seem to be explained by diabetes mellitus, the main comorbidity in our cohort, since the prevalence of neuropathy in diabetic individuals is estimated at around 50%, which would correspond to a significantly lower proportion of affected patients than that observed.

These observations suggest that mild-to-moderate neuropathy, whether large-fiber, small-fiber, or both, is highly prevalent in ATTRwt amyloidosis. Given that several drugs are currently indicated for mild-to-moderate neuropathy in ATTRv (eg, patisiran and inotersen), it is conceivable that their indications could be expanded to ATTRwt amyloidosis in the light of these results.

Finally, cognitive screening with the Fototest did not seem to find significant impairment in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis: 18.2% of our patients scored ≤28, while the majority (72.7%) presented normal scores. These scores appear comparable to reference marks for men >65 years who have completed primary studies: around 16% score ≤28 on the Fototest.35

We attempted to find a statistical correlation between the altered results in NCS and the Sudoscan® (using the Fisher test), as well as between these and clinical and functional questionnaire scores (using the Mann–Whitney U test). However, this association could not be demonstrated due to the small sample size.

This study is modest, but has the following strengths. Firstly, it achieves comprehensiveness in clinical and functional information through the use of a diverse array of questionnaires and procedures. In addition, the integration of Sudoscan® and NCS serves as a particularly effective combination, as these tests complement one another to enhance the accuracy of neuropathy detection and characterization. Furthermore, the incorporation of the Fototest introduces a novel method for investigating potential cognitive involvement in ATTRwt amyloidosis, marking an innovative approach in the study of this disease. These attributes ensure that our work stands as a reliable and comprehensive resource to widen the understanding of neurological involvement in ATTRwt amyloidosis. However, this study has several limitations. Firstly, some data were gathered retrospectively, which introduces inherent biases in the analysis. In addition, the study design, with a single cross-sectional analysis, does not allow for the determination of causality, while the sample size, though comparable to those of other published series, is insufficient to establish statistically significant correlations between variables. Moreover, cognitive impairment was imprecisely formulated as an exclusion criterion, since its presence was based on patients’ past clinical records. Finally, the lack of imaging studies to assess potential central nervous system involvement, as well as the absence of peripheral nerve biopsies, represents a significant limitation in the study's diagnostic scope.

Future research should aim to use a stronger study design, with better-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria and a larger number of patients. It would be beneficial for new participants to join this cohort, in order to study the correlation between variables such as NCS and ESC results. Additionally, all participants should be followed up in successive consultations. Thus, a prospective study could be carried out, which, in addition to causality data, would provide information on disease progression and treatment response.

ConclusionThe findings of this study lead to several important conclusions regarding patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis. Firstly, large-fiber polyneuropathy, mainly axonal and either sensory or sensorimotor, is highly prevalent in individuals with ATTRwt amyloidosis. Secondly, the strong association between this condition and bilateral CTS is corroborated. Additionally, a significant percentage of patients exhibit small-fiber neuropathy, which is often mild in nature. But, unlike in ATTRv amyloidosis, the polyneuropathy in patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis has a mild-to-moderate impact on functional capacity, although it does reduce their quality of life. Therefore, this study advocates for a more comprehensive evaluation of patients with ATTRwt amyloidosis in both clinical and research settings. Furthermore, it contributes to a better characterization of neuropathic involvement in this disease, which could promote improved symptomatic treatment and even lead to therapeutic innovations.

Ethical approvalResearch Ethics Committee of the San Carlos Clinical Hospital (code: 22/439-E).

Declaration of competing interestsThe authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr Susana Martín, specialist physician in clinical neurophysiology at Hospital Clínico San Carlos, for her important contributions regarding nerve conduction studies, and to Nines Martín Arribas for her invaluable assistance and support during the publication of this work.