Dementias currently impose a significant burden in terms of morbidity, mortality, socio-economic costs, and human suffering. Several studies have indicated that certain infectious diseases may increase the risk of dementia. Additionally, research has suggested that adult vaccines may help to prevent dementia. This systematic review looks into the possible association between adult vaccines and dementia in studies published between 2016 and April 2024.

DevelopmentA search was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to assess the potential association between adult vaccines and dementia in adults aged 50 and above. Quality and potential bias were evaluated using the revised Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) scale, the Newcastle–Ottawa scale, and the Risk-of-bias in Studies of Temporal Trends (ROBITT) tool. Fifteen out of the 16 selected studies showed a high degree of uniformity in terms of vaccinated adults having lower rates of dementia than unvaccinated adults. The observed risk reduction ranged from 4% to 50% (relative risk measures). The influenza vaccine has been the subject of the most extensive research, with 10 of the 16 studies focusing on it. Five studies demonstrated a dose–response relationship, indicating that a higher number of vaccines per patient is associated with a lower risk of dementia. Only one of the selected studies found an association between vaccination of adults and an increased risk of dementia.

ConclusionsThe studies examined provide evidence supporting the hypothesis that adult vaccination may have a protective effect against the development of dementia. However, further molecular biology and pathophysiology studies are required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and confirm the plausibility of this hypothesis.

En la actualidad, las demencias conllevan una carga importante en términos de morbilidad, mortalidad, coste socioeconómico y sufrimiento humano. Varios estudios han señalado que determinadas enfermedades infecciosas pueden aumentar el riesgo de demencia. Además, algunos estudios sugieren que la vacunación en adultos puede ayudar a prevenir la demencia. Esta revisión sistemática ahonda en la posible asociación entre la vacunación durante la edad adulta y la demencia reportada en estudios publicados entre 2016 y abril de 2024.

DesarrolloRealizamos una búsqueda bibliográfica siguiendo la declaración PRISMA 2020 para valorar la posible asociación entre la vacunación en la edad adulta y la demencia en individuos de 50 o más años de edad. Evaluamos la calidad y los posibles sesgos mediante la escala revisada Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews, la escala Newcastle-Ottawa y la herramienta Risk-of-Bias in Studies of Temporal Trends. De los 16 estudios seleccionados, 15 mostraron que los adultos vacunados presentaban tasas de demencia menores que los adultos que no habían recibido vacunas. Esta reducción del riesgo observada osciló entre el 4% y el 50% (riesgo relativo). La vacuna de la gripe ha sido objeto del mayor número de investigaciones, con 10 de los 16 estudios centrados en este tema. Cinco estudios demostraron una relación dosis-respuesta, según la cual cuanto mayor es el número de vacunas por paciente, menor es el riesgo de padecer demencia. Solo uno de los estudios seleccionados encontró una asociación entre la vacunación en adultos y un mayor riesgo de demencia.

ConclusionesLos estudios analizados apoyan la hipótesis de que las vacunas en adultos tienen un efecto protector contra el desarrollo de demencia. Sin embargo, se necesitan más estudios de biología molecular y fisiopatológicos para dilucidar los mecanismos subyacentes y confirmar esta hipótesis.

The World Health Organization estimates that dementias affect more than 55 million adults worldwide, affecting approximately 5–8% of individuals aged over 60, with 10 million new cases being diagnosed each year.1 Dementia is one of the main causes of disability and dependence among older adults and is currently the seventh leading cause of death worldwide. By 2030, 78 million people are expected to have some form of dementia; by 2050, this number could reach 139 million.2 In addition to the economic, health, and social costs, dementia causes significant human suffering for patients and their families.

Population ageing poses challenges of great relevance to public health policies, such as the possibility of increasing the number of years of healthy life, with a higher quality of life. To achieve these objectives, the prevention of neurodegenerative disorders whose pathophysiology is not yet well understood may be fundamental.3

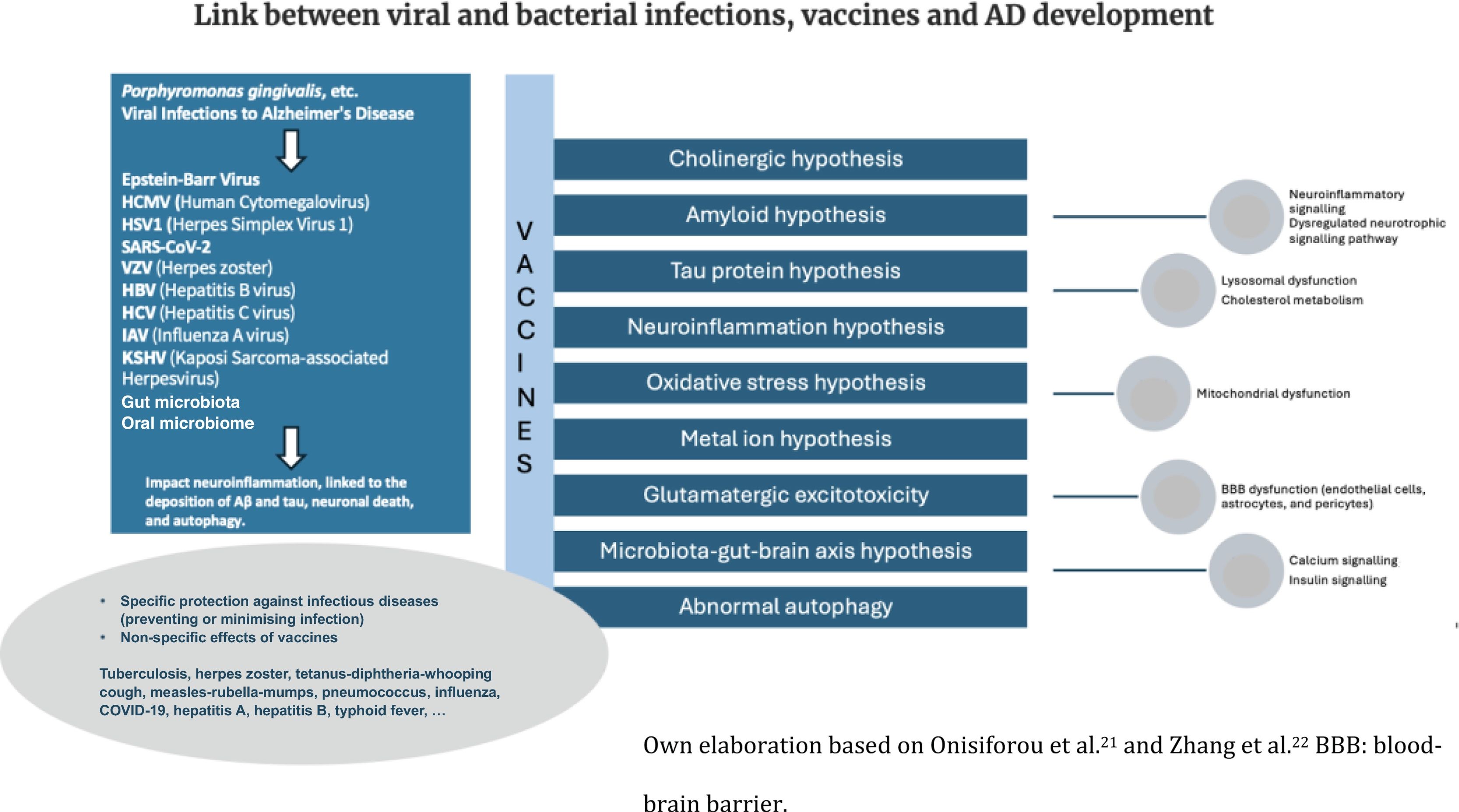

For decades, the hypothesis that microbial organisms may contribute to the pathophysiology of dementia has been proposed and debated.4 Microorganisms responsible for viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections have been proposed to be among the many risk factors for neurodegenerative disorders.5–9 Studies have shown that infection with herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus, varicella zoster virus, Epstein–Barr virus, hepatitis C virus, or pneumococcus play a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases, although the mechanisms involved in this viral or bacterial pathogenesis have not yet been established.6,10 Furthermore, older people are more likely to suffer from immunosenescence, which leads to increased susceptibility to infections, neoplasms, and inflammatory processes.5 These 2 factors, increased vulnerability to age-related infections and the involvement of microorganisms in the pathophysiology of cognitive disorders, constitute a combination that may at least partially explain the increased incidence of dementia with ageing. Mechanisms, such as inflammation, epigenetic and hypercoagulable changes, or a direct or indirect viral effect, may affect brain structure and function in healthy or cognitively impaired individuals.5,11,12

The beneficial effects of human vaccines developed to prevent specific infectious diseases are well known. On the other hand, some recent epidemiological and immunological studies have shown other non-specific effects associated with the use of vaccines, such as their relationship with a decrease in morbidity and mortality due to non-infectious causes, such as acute myocardial infarction, or pathologies related to cognitive disorders.11–15 Whitson et al.4 highlight the potential for infections to lead to systemic inflammatory neurotoxicity.

Consequently, vaccination could offer 2 key benefits: (1) reducing neurotoxic inflammation or microbial damage induced by infection, and (2) exerting nonspecific protection against infectious and other diseases by influencing the microglia and oxidative stress.

Several investigations have suggested that influenza vaccination may reduce the neuroinflammatory state observed in patients already affected by cardiovascular morbidities, thus protecting cerebral vessels against the typical damage occurring in dementias.16,17 Regardless of the protective effect of vaccines against specific microorganisms, it has been known since the last century that vaccines can induce protective non-specific or heterologous effects.15,18 Heterologous T-cell immunity due to structural similarity between the epitopes of a pathogen and those of some host proteins or other pathogens affects not only the immune response against the target pathogen but also cross-reactivity with other pathogens. Immunological mechanisms mediating non-specific effects include these heterologous lymphocyte effects and the induction of innate immune memory (trained immunity). Trained immunity induces long-term functional regulation of innate immune cells through epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming.11,12,15 Any vaccine can have non-specific effects because microbial antigens in vaccines stimulate an innate immune response through pattern recognition receptors on immune cells.19

Neurodegeneration has been linked to microglia-associated inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-1β. In this state, microglia fail to endocytose pathological Aβ and tau, and Aβ and tau deposition contributes to inflammatory activation, resulting in a vicious cycle in AD pathology.20 Vaccinations have been shown to induce a type of reprogramming of innate immune cells, including cytokines, and positive regulation of NK cell receptors and monocytes. Cytokine alterations directly impact the efficacy of the microglia in clearing CNS protein aggregates. Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the potential interactions between vaccines and the pathophysiology of AD, based on the work of Onisiforou et al.21 and Zhang et al.22

This systematic review will focus on the current knowledge about the possible effect of vaccines in reducing the incidence of dementia. A notable increase in the number of publications on this topic has been observed over the past 4 years, with a particular focus on the association between vaccinations received during adulthood (after 50 years of age) and the risk of dementia.

According to the hypothesis that vaccines may protect against dementia, the following question was posed: does adult vaccination reduce the incidence of dementia? As a secondary objective, we sought to investigate whether there is a dose–response relationship between the number of adult vaccines received and the degree of protection against the development of dementia.

MethodologyStudy designA systematic review was conducted to assess whether adult populations vaccinated against several infectious diseases have lower rates of dementia than unvaccinated populations. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO (CRD42024539713) and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42024539713.

Inclusion criteriaThe selection of papers was conducted in accordance with 5 eligibility criteria:

- 1)

Published between 2016 and May 2024, inclusive. The decision to limit the scope of the study to articles published in 2016 or later is based on the observation that prior to 2014, most studies examining non-specific effects of vaccines focused on childhood vaccines and life expectancy.

- 2)

Research into the potential link between adult vaccines and cognitive disorders and/or dementia. Analyses of other relationships were excluded from consideration.

- 3)

Studies employing descriptive designs, observational studies, clinical trials, systematic reviews, or meta-analyses. The review process excluded narrative reviews and opinion pieces.

- 4)

Studies involving adults over 50 years of age, as vaccinations in adulthood are more commonly administered after this age, and the likelihood of a dementia diagnosis increases thereafter.

- 5)

Published in English, French, or Spanish.

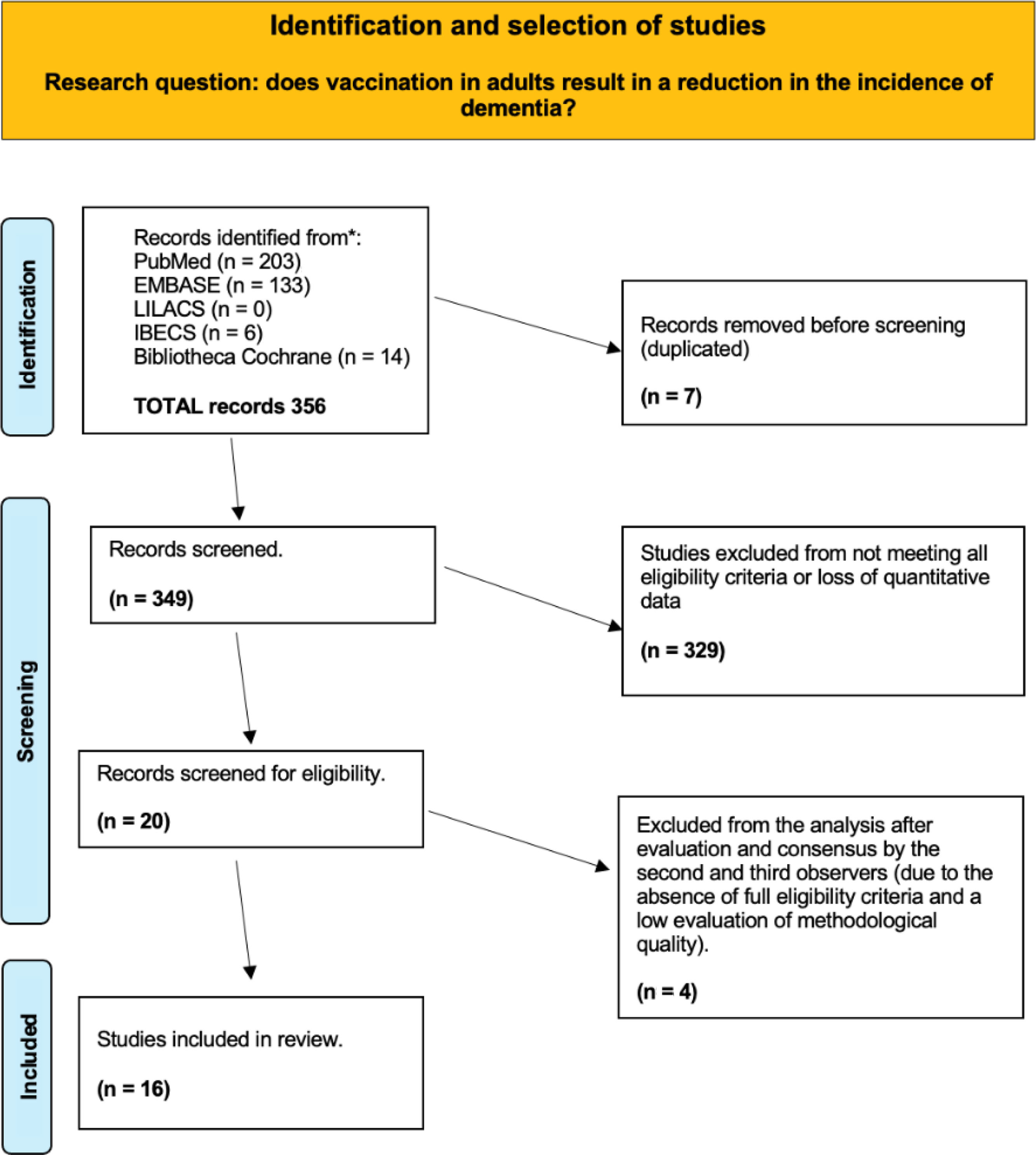

The present systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines.23 The MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, Cochrane Library, LILACS, IBECS, and Web of Science databases were independently and extensively reviewed by 2 authors (MGC and EML) to identify relevant studies published between 2016 and 2024. We used the following terms and search strategy:

PUBMED: (“Vaccination”[MeSH]) AND “Dementia”[MeSH]); “vaccination against infectious disease” [Supplementary Concept] AND “Neurocognitive Disorders”[MeSH]. Filtered by years (2016–2024) and by age of the population (≥ 50 years). Last accessed May 2024.

EMBASE: (‘vaccination’/exp OR vaccination) AND (‘dementia risk’ OR ((‘dementia’/exp OR dementia) AND (‘risk’/exp OR risk))) AND vaccination:ti,ab,kw AND dementia:ti,ab,kw. Filtered by years (2016–2024) and by age of the population (≥ 50 years). Last accessed May 2024.

For eligible studies, 3 authors collected the following information: the name of the first author, the year of publication, the name of the journal, the geographical area of the population studied, the epidemiological design of the study, the duration of follow-up, the sample size, and the measures or outcomes related to the study (exposures and outcomes). All 3 authors reached a consensus to resolve any disagreement regarding the choice of articles.

The type of study design, number of participants, valid results of each study, and quality criteria were previously established as the most important characteristics for the analysis.

Quality and risk of bias assessmentTo assess the strength of the evidence, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was employed. The GRADE framework offers a structured approach to evaluation, delineating the essential elements and analytical techniques. This system categorises the level of evidence into 4 distinct categories: high, moderate, low, and very low quality. The bias assessment of selected studies was evaluated using a scale adapted to the epidemiological design of the study:

- -

The Assessment of Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR-2) tool was used to assess systematic reviews and meta-analyses,24 according to a procedure consisting of a checklist of 16 questions resulting in 4 levels of quality: high (no or one non-critical weakness), moderate (more than one non-critical weakness), low (one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses), and critically low (more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses).

- -

Cohort and case–control studies were assessed for risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysis (NOS),24,25 which examines potential bias in selection, comparability, and outcome. This tool yields a total NOS score ranging from 0 to 10 for cross-sectional studies, and from 0 to 9 for case-control and cohort studies, identifying total scores≤4 as high risk of bias, scores 5–6 as moderate risk, and scores≥7 as low risk of bias.

- -

Descriptive ecological studies with aggregated variables were assessed using the Risk-of-bias in studies of Temporal Trends (ROBITT) tool, which comprises 17 questions.26

In order to assess the quality of the selected studies and potential biases, data extraction forms were created. These forms were completed independently by 2 reviewers (MGC and RLG), and subsequently by a third coauthor (EML) if consensus was required.

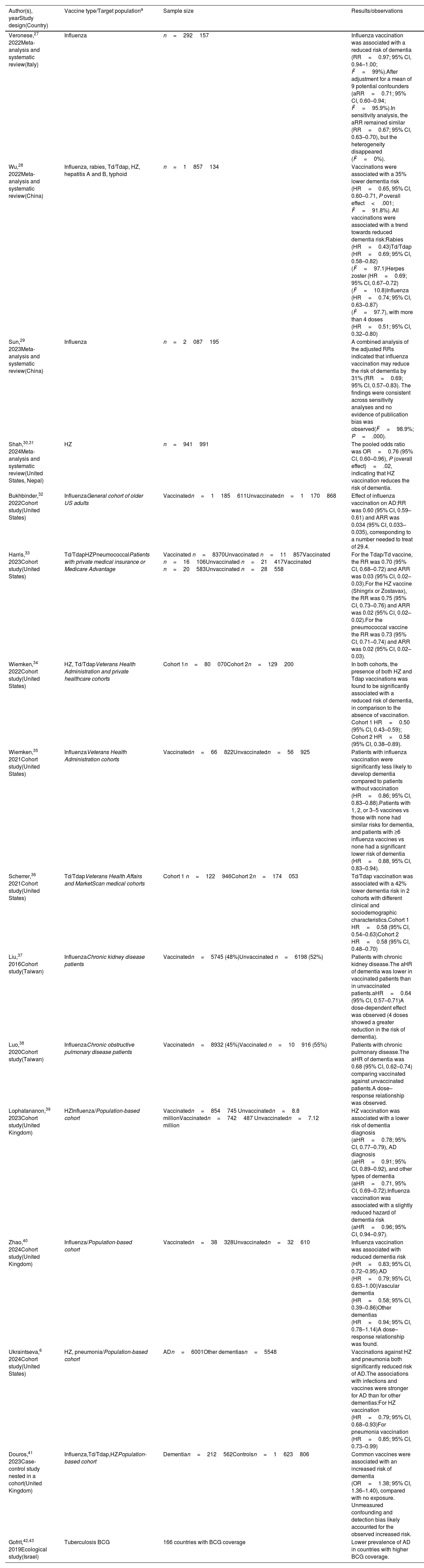

ResultsSearch processThe systematic literature search returned 349 unique records after checking for duplicates (Fig. 2). Following a thorough review, 329 studies were excluded from the analysis, either because the vaccines were administered after the diagnosis of dementia, because they studied therapeutic vaccines, or because of non-compliance with inclusion and exclusion criteria or methodological flaws. Finally, 16 studies, whose descriptions are detailed in Table 1, were selected for qualitative analysis.

Synthesis of the results of the 16 selected studies.

| Author(s), yearStudy design(Country) | Vaccine type/Target populationa | Sample size | Results/observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Veronese,27 2022Meta-analysis and systematic review(Italy) | Influenza | n=292157 | Influenza vaccination was associated with a reduced risk of dementia (RR=0.97; 95% CI, 0.94–1.00; I2=99%).After adjustment for a mean of 9 potential confounders (aRR=0.71; 95% CI, 0.60–0.94; I2=95.9%).In sensitivity analysis, the aRR remained similar (RR=0.67; 95% CI, 0.63–0.70), but the heterogeneity disappeared (I2=0%). |

| Wu,28 2022Meta-analysis and systematic review(China) | Influenza, rabies, Td/Tdap, HZ, hepatitis A and B, typhoid | n=1857134 | Vaccinations were associated with a 35% lower dementia risk (HR=0.65, 95% CI, 0.60–0.71, P overall effect<.001; I2=91.8%). All vaccinations were associated with a trend towards reduced dementia risk:Rabies (HR=0.43)Td/Tdap (HR=0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.82) (I2=97.1)Herpes zoster (HR=0.69; 95% CI, 0.67–0.72) (I2=10.8)Influenza (HR=0.74; 95% CI, 0.63–0.87) (I2=97.7), with more than 4 doses (HR=0.51; 95% CI, 0.32–0.80) |

| Sun,29 2023Meta-analysis and systematic review(China) | Influenza | n=2087195 | A combined analysis of the adjusted RRs indicated that influenza vaccination may reduce the risk of dementia by 31% (RR=0.69; 95% CI, 0.57–0.83). The findings were consistent across sensitivity analyses and no evidence of publication bias was observed(I2=98.9%; P=.000). |

| Shah,30,31 2024Meta-analysis and systematic review(United States, Nepal) | HZ | n=941991 | The pooled odds ratio was OR=0.76 (95% CI, 0.60–0.96), P (overall effect)=.02, indicating that HZ vaccination reduces the risk of dementia. |

| Bukhbinder,32 2022Cohort study(United States) | InfluenzaGeneral cohort of older US adults | Vaccinatedn=1185611Unvaccinatedn=1170868 | Effect of influenza vaccination on AD:RR was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.59–0.61) and ARR was 0.034 (95% CI, 0.033–0.035), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 29.4. |

| Harris,33 2023Cohort study(United States) | Td/TdapHZPneumococcalPatients with private medical insurance or Medicare Advantage | Vaccinated n=8370Unvaccinated n=11857Vaccinated n=16106Unvaccinated n=21417Vaccinated n=20583Unvaccinated n=28558 | For the Tdap/Td vaccine, the RR was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.68–0.72) and ARR was 0.03 (95% CI, 0.02–0.03).For the HZ vaccine (Shingrix or Zostavax), the RR was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.73–0.76) and ARR was 0.02 (95% CI, 0.02–0.02).For the pneumococcal vaccine the RR was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.71–0.74) and ARR was 0.02 (95% CI, 0.02–0.03). |

| Wiemken,34 2022Cohort study(United States) | HZ, Td/TdapVeterans Health Administration and private healthcare cohorts | Cohort 1n=80070Cohort 2n=129200 | In both cohorts, the presence of both HZ and Tdap vaccinations was found to be significantly associated with a reduced risk of dementia, in comparison to the absence of vaccination. Cohort 1 HR=0.50 (95% CI, 0.43–0.59); Cohort 2 HR=0.58 (95% CI, 0.38–0.89). |

| Wiemken,35 2021Cohort study(United States) | InfluenzaVeterans Health Administration cohorts | Vaccinatedn=66822Unvaccinatedn=56925 | Patients with influenza vaccination were significantly less likely to develop dementia compared to patients without vaccination (HR=0.86; 95% CI, 0.83–0.88).Patients with 1, 2, or 3–5 vaccines vs those with none had similar risks for dementia, and patients with ≥6 influenza vaccines vs none had a significant lower risk of dementia (HR=0.88, 95% CI, 0.83–0.94). |

| Scherrer,36 2021Cohort study(United States) | Td/TdapVeterans Health Affairs and MarketScan medical cohorts | Cohort 1 n=122946Cohort 2n=174053 | Td/Tdap vaccination was associated with a 42% lower dementia risk in 2 cohorts with different clinical and sociodemographic characteristics.Cohort 1 HR=0.58 (95% CI, 0.54–0.63)Cohort 2 HR=0.58 (95% CI, 0.48–0.70) |

| Liu,37 2016Cohort study(Taiwan) | InfluenzaChronic kidney disease patients | Vaccinatedn=5745 (48%)Unvaccinated n=6198 (52%) | Patients with chronic kidney disease.The aHR of dementia was lower in vaccinated patients than in unvaccinated patients.aHR=0.64 (95% CI, 0.57–0.71)A dose-dependent effect was observed (4 doses showed a greater reduction in the risk of dementia). |

| Luo,38 2020Cohort study(Taiwan) | InfluenzaChronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients | Vaccinatedn=8932 (45%)Vaccinated n=10916 (55%) | Patients with chronic pulmonary disease.The aHR of dementia was 0.68 (95% CI, 0.62–0.74) comparing vaccinated against unvaccinated patients.A dose–response relationship was observed. |

| Lophatananon,39 2023Cohort study(United Kingdom) | HZInfluenza/Population-based cohort | Vaccinatedn=854745 Unvaccinatedn=8.8 millionVaccinatedn=742487 Unvaccinatedn=7.12 million | HZ vaccination was associated with a lower risk of dementia diagnosis (aHR=0.78; 95% CI, 0.77–0.79), AD diagnosis (aHR=0.91; 95% CI, 0.89–0.92), and other types of dementia (aHR=0.71, 95% CI, 0.69–0.72).Influenza vaccination was associated with a slightly reduced hazard of dementia risk (aHR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.94–0.97). |

| Zhao,40 2024Cohort study(United Kingdom) | Influenza/Population-based cohort | Vaccinatedn=38328Unvaccinatedn=32610 | Influenza vaccination was associated with reduced dementia risk (HR=0.83; 95% CI, 0.72–0.95).AD (HR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.63–1.00)Vascular dementia (HR=0.58; 95% CI, 0.39–0.86)Other dementias (HR=0.94; 95% CI, 0.78–1.14)A dose–response relationship was found. |

| Ukraintseva,6 2024Cohort study(United States) | HZ, pneumonia/Population-based cohort | ADn=6001Other dementiasn=5548 | Vaccinations against HZ and pneumonia both significantly reduced risk of AD.The associations with infections and vaccines were stronger for AD than for other dementias:For HZ vaccination (HR=0.79; 95% CI, 0.68–0.93)For pneumonia vaccination (HR=0.85; 95% CI, 0.73–0.99) |

| Douros,41 2023Case-control study nested in a cohort(United Kingdom) | Influenza,Td/Tdap,HZPopulation-based cohort | Dementian=212562Controlsn=1623806 | Common vaccines were associated with an increased risk of dementia (OR=1.38; 95% CI, 1.36–1.40), compared with no exposure. Unmeasured confounding and detection bias likely accounted for the observed increased risk. |

| Gofrit,42,43 2019Ecological study(Israel) | Tuberculosis BCG | 166 countries with BCG coverage | Lower prevalence of AD in countries with higher BCG coverage. |

AD: Alzheimer disease; aHR: adjusted hazard ratio; aRR: adjusted relative risk; ARR: absolute risk reduction; BCG: Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine; CI: confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; HZ: herpes zoster; OR: odds ratio; RR: relative risk; Td: tetanus and diphtheria; Tdap: tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis.

The studies analysed included 4 systematic reviews and meta-analyses, 11 observational studies (10 cohort and one case-control), and one ecological study; no clinical trials related to this subject or other epidemiological designs were found.

Results of the studies analysedAs shown in Table 1, the studies analysed in the systematic review over the past 9 years have yielded consistent results, suggesting a possible protective effect of routine adult vaccines against dementia and neurodegenerative disorders. Fifteen of the 16 publications identified a protective effect of vaccines against the development of dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases, with varying degrees of scientific evidence (II++ to IV). Only one study found a direct association between vaccination and dementia.

Participants in the studies were over 50 years old (inclusion criteria), and the populations size ranged from 11943 to 2087195 individuals. The studies examined different types of vaccines, including influenza, pneumonia, shingles, tuberculosis, rabies, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, hepatitis A, typhoid, and hepatitis B. Seven of the studies included more than one vaccine. The influenza vaccine was the most extensively studied vaccine among the selected papers, included in 10 of the 16 studies analysed. Other vaccines appearing in several studies were the herpes zoster vaccine, included in 7 studies, and the tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (Tdap) combined vaccine, included in 5.

The efficacy of different vaccines in the prevention of dementia shows considerable variability. The observed risk reduction ranged from 4%39 to 57%.34 The study by Wu et al.26 offers the best, statistically significant data about vaccine protection against dementia: the herpes zoster vaccine showed a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.69 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.66–0.73), whereas the Tdap vaccine presented a HR of 0.69 (95% CI, 0.58–0.82). Both vaccines showed the highest protection observed in this study; this result was statistically significant.28

The protection offered by influenza vaccines varies considerably. The study by Lophatananon39 revealed an adjusted HR (aHR) of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.94–0.97) for the influenza vaccine. In contrast, the study by Luo38 found a 32% reduction in the risk of dementia (aHR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.62–0.74) for the same vaccine. Similarly, the meta-analysis conducted by Sun et al.29 revealed that influenza vaccination is associated with a 31% reduction in the risk of dementia (aRR=0.69; 95% CI, 0.57–0.83).

The herpes zoster vaccine showed variable protection rates, with estimates ranging from 22%39 to 31%.28 Vaccination against tetanus and diphtheria (Td) or tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis (Tdap) showed protection against the development of dementia, with an estimated efficacy range of between 30%33 and 42%.36 Wiemkem et al.34 evaluated the efficacy of 2 vaccines, herpes zoster and Tdap, in preventing dementia. Their findings indicated that adults receiving both vaccines had an additive protective effect against dementia, with an estimated efficacy range of 42–50%.

In contrast, Douros et al.41 found that common adult vaccinations were associated with an increased risk of dementia (OR=1.38; 95% CI, 1.36–1.40), compared with no exposure.

Five studies28,35,37,38,40 examined the relationship between the number of influenza vaccine doses administered and the resulting reduction in the risk of dementia. Their results indicated a dose–response effect, whereby a greater number of doses resulted in a greater reduction in the risk of dementia. The cohort study by Wiemken et al.35 indicates that influenza-vaccinated patients exhibit a reduction in the risk of developing dementia following the administration of at least 6 doses.

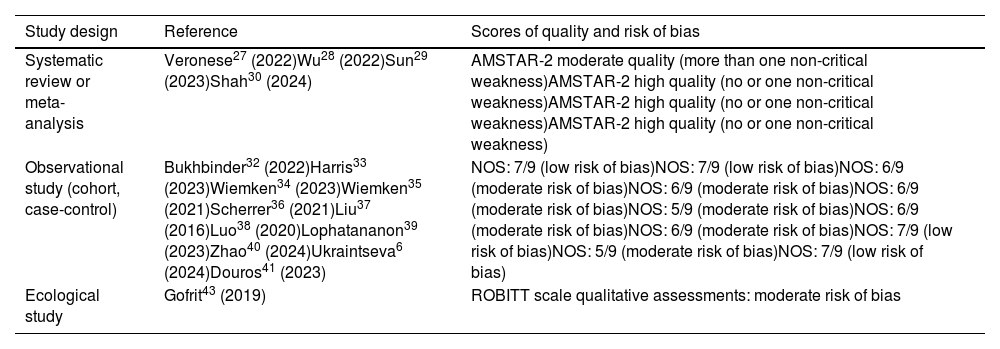

Study qualityFifteen of the included studies were meta-analyses or observational studies (cohorts and case-controls) with scientific evidence levels of 2++ or 2+ (moderate confidence in the effect estimate). In addition, one ecological study was included, with scientific evidence levels of 3 and 4 (limited confidence in the estimate of the effect). The observational studies and meta-analyses were of high quality, and the majority demonstrated a protective relationship between vaccines and the risk of developing dementia.

Study biasTable 2 presents the risk of bias assessment of the 16 studies analysed. The 4 meta-analysis and systematic review studies27–30 obtained favourable ratings, with minimal critical weaknesses as measured by AMSTAR-2. The 11 observational studies (10 cohort and one case-control) showed favourable scores on the NOS, with values between 5 and 7. The ecological study was evaluated using qualitative ratings of the ROBITT scale, which led us to conclude that there was a moderate risk of bias.42

Risk of bias assessment.

| Study design | Reference | Scores of quality and risk of bias |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic review or meta-analysis | Veronese27 (2022)Wu28 (2022)Sun29 (2023)Shah30 (2024) | AMSTAR-2 moderate quality (more than one non-critical weakness)AMSTAR-2 high quality (no or one non-critical weakness)AMSTAR-2 high quality (no or one non-critical weakness)AMSTAR-2 high quality (no or one non-critical weakness) |

| Observational study (cohort, case-control) | Bukhbinder32 (2022)Harris33 (2023)Wiemken34 (2023)Wiemken35 (2021)Scherrer36 (2021)Liu37 (2016)Luo38 (2020)Lophatananon39 (2023)Zhao40 (2024)Ukraintseva6 (2024)Douros41 (2023) | NOS: 7/9 (low risk of bias)NOS: 7/9 (low risk of bias)NOS: 6/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 6/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 6/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 5/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 6/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 6/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 7/9 (low risk of bias)NOS: 5/9 (moderate risk of bias)NOS: 7/9 (low risk of bias) |

| Ecological study | Gofrit43 (2019) | ROBITT scale qualitative assessments: moderate risk of bias |

AMSTAR-2: Assessment of Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews; NOS: Newcastle–Ottawa scale; ROBITT: Risk-Of-Bias in studies of Temporal Trends.

This systematic review presents evidence suggesting a protective effect of vaccines against the development of dementia in 15 of the 16 studies evaluated. Only one of the selected studies found an association between adult vaccination and increased risk of dementia.41 One possible explanation for this finding is that vaccinated participants may have had a higher prevalence of other risk factors for dementia compared to those who were not vaccinated. The vaccinated cases and controls were, on average, more ill than the unvaccinated cases and controls (e.g., arterial hypertension: 35.5% vs 25%; coronary artery disease: 12.8% vs 7.9%, etc.). Furthermore, the proportion of smokers was significantly higher in the vaccinated group than in the unvaccinated group. Additionally, the average monitoring period was 11.1 years for vaccinated individuals and 7.5 years for unvaccinated individuals.

The development of dementia, which is clearly a multifactorial pathology, is often related to lifestyle, social, and environmental factors, in addition to genetic and epigenetic factors. Numerous studies have analysed ways to reduce the global burden of dementia. In a study employing population attributable fractions (PAFs), the Lancet Commission on Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care estimated that 39.7% of dementia cases worldwide were attributable to 12 potentially modifiable risk factors: low levels of education, hearing loss, hypertension, obesity, smoking, depression, social isolation, physical inactivity, diabetes, excessive alcohol consumption, traumatic brain injury, and air pollution.44 Vaccination throughout life has not yet been assessed as a protective factor.

Poynton-Smith et al.18 assessed the potential causal link between adult vaccines and dementias using the 9 Bradford-Hill criteria, concluding that the hypothesis is plausible and coherent because there is a strong and consistent association, with a clear biological dose-effect gradient and an established temporality. The fulfilment of these criteria makes the causal nature of this association more likely.

The majority of the reviewed publications consistently support the study hypothesis that routine adult vaccinations have a protective effect on the development of dementias. Other narrative reviews not included in this systematic review also report protective effects of adult vaccines against dementia.45–47 However, further pathophysiological studies are needed to assess and understand whether routine vaccination of the adult population really helps to reduce the incidence of dementia.

In recent years, several epidemiological studies (Bohn et al.,9 Janbek et al.,8 and Sipilä et al.7) have assessed and quantified the risk of dementia associated with infectious diseases. However, a prospective study conducted in 2016 found no association between infectious processes and the development of dementia.48 Nonetheless, some studies have included the prevention of infections in their lists of factors that can reduce the risk of dementia.49

The preventive benefits of vaccines against infectious diseases are widely known, but this study aims to consider another type of benefit: the effect of vaccination on the immune system and inflammation,48 because this may result in a reduction in the incidence of dementia.19,50 Immunological studies have identified several mechanisms by which vaccines may modulate the immune response to unrelated pathogens. These include trained innate immunity, emergency granulopoiesis, and heterologous T-cell immunity.50

Lophatananon et al.39 found that both the herpes zoster vaccine and the influenza vaccine were associated with a lower risk of dementia. The association was more pronounced with the shingles vaccine.39 Similarly, 2 recent studies have yielded initial results indicating a reduction in AD among shingles-vaccinated cohorts.30,51 Harris et al.33 also proposed that recombinant vaccinations, when compared with live attenuated vaccinations, and conjugated vaccinations, when compared with unconjugated vaccinations, are associated with a greater decrease in dementia risk, due to the stronger protection against infectious disease from Shingrix (compared to Zostavax) and the more robust adaptive immune response induced by conjugated vaccines. A 2021 study of US veterans found that patients over 65 years of age who received at least one influenza vaccination were 40% less likely to develop dementia for at least 4 years than those who were unvaccinated.35 The authors calculated that it would be possible to prevent one case of dementia for every 30 vaccinated individuals. Several studies found that reductions in dementia risk may be related to the number of doses. The dose-dependent effect was especially studied with influenza vaccines.34,35,37 Individuals with full vaccination against more types and with more annual influenza vaccinations were less likely to develop dementia. Five of the studies analysed found a dose–response relationship: the greater the number of doses, the greater the protection against dementia.28,35,37,38,40 Wiemken et al.34,35 found that the beneficial effect is dose-dependent, and that patients older than 65 years have a 12% lower risk of developing dementia if they received 6 or more influenza vaccines (HR=0.88; 95% CI, 0.83–0.94).

Vaccines represent one of the most significant public health innovations in human history. Despite the clear benefits, the most recent data from the Commonwealth Fund indicates that the 2021 influenza vaccination rate for US adults was just 42%. In contrast, during the 2022–2023 school year, 93% of kindergarten students received all state-required vaccines. In Spain, during the 2023–2024 influenza season, the coverage rate among adults over 65 years of age was 67%, while the rate among healthcare personnel was 42%. These figures indicate the need to implement adherence efforts, including the development of educational programmes that address novel aspects of protection, such as protection against the dementias addressed in this study. In general, routine vaccinations are highly cost-effective in children, young people, and adults, and they are critical components of routine healthcare for adults. Despite this, at least three-quarters of adults in the United States do not receive one or more routinely recommended vaccines.52 Policies and programmes designed to enhance vaccine coverage rates among adults aged 50 years or older are limited, and vaccine uptake is often suboptimal.53,54 It is conceivable that enhanced awareness and dissemination among healthcare professionals of the benefits of vaccines in the prevention of dementias may contribute to improved vaccination coverage in adults.

LimitationsIn examining the relationship between vaccination and dementia reduction in adult populations, it is challenging to assess potential biases. Vaccinated adult populations are often not representative of the general population, and vaccination is often viewed as an indicator of a healthy lifestyle. Consequently, in general, a population's high socioeconomic status is positively associated with the intention to receive vaccinations. However, most of the observational studies reviewed adjusted their results for income level, level of education, and related variables. It should be noted that all selected studies refer to people (general population, insured or patient cohorts) over 50 years of age, without specifying differences between the different age subgroups. In addition, there is a lack of data on gender differences.

It is also important to note that some studies selected for this review had been reviewed in the systematic reviews and meta-analyses also included in our selection, resulting in some redundancy.

The extensive scope of the review, encompassing numerous vaccines (e.g., influenza, pneumonia, shingles, tuberculosis, rabies, tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis, hepatitis A) introduces a degree of uncertainty regarding the conclusiveness of our results. A separate review would be required for each type of vaccine.

Moreover, it is of paramount importance to recognise that the pathophysiological mechanisms that cause dementia remain poorly understood. Dementias are a heterogeneous group of diseases of a complex, multifactorial nature, with uncertainties regarding the main causal factors and the precise sequence of events leading to neurodegeneration. Therefore, knowledge and understanding of the impact of vaccines, as immunomodulatory agents, is highly complex, and there is a need to better understand the effects of vaccines on anti-inflammatory mechanisms, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, neurotrophic factors, gut dysbiosis, etc.

ConclusionsThe results of 15 out of the 16 studies reviewed indicate that adult populations who have received vaccinations against a variety of infectious diseases present lower prevalence of dementia than those who have not been vaccinated. The findings indicate the potential benefits of improving routine vaccination coverage among individuals aged 50 and above, including both healthy adults and those at risk. This approach significantly enhances the efficiency of adult vaccinations. We propose the addition of adult vaccinations to the list of factors that reduce the risk of dementia.

The observed association between influenza vaccination and reduced risk of dementia is consistent with the hypothesis that protection is dose dependent. Studies have shown that annual influenza vaccination is associated with enhanced protection against dementia, with 3–6 vaccinations.

Further research is required to substantiate the association between vaccinations and protection against dementia. In addition, the mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear. The proposal of future studies would be significantly enhanced by the incorporation of comprehensive monitoring of multimodal biomarkers in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, across both living and deceased cohorts, with a confirmed postmortem diagnosis.