Previous research suggests that amantadine could be effective as an antiepileptic drug. We evaluate the use of the drug in children with refractory generalised epilepsy.

MethodRetrospective study of children with developmental and/or epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation in sleep (D/EE-SWAS) or generalised epilepsy with refractory absence seizures treated with amantadine at a paediatric hospital in Madrid, Spain, over a 3-year period.

ResultsWe studied 12 children treated with amantadine for refractory epilepsy at a median age of 9.5 years (range, 3–11) and a median disease duration of 5 years (range, 1–8). Before initiation of amantadine, the patients had received 9.4 antiepileptic drugs on average (range, 6–14), and 9 had been placed on a ketogenic diet. Brain MRI displayed no structural lesion in any patient, except for one with a thalamic lesion. All patients had idiopathic epilepsy, and MRI results were normal. Five were diagnosed with D/EE-SWAS, and 7 had generalised epilepsy with refractory absence seizures (5 with refractory absence epilepsy, one with eyelid myoclonia with absence seizures, and one with Lennox–Gastaut syndrome). Amantadine was added to other antiepileptic drugs (mean number of drugs administered, 2.7) at a mean dose of 5.6mg/kg/day, with a maximum dose of 300mg/day. In the group with D/EE-SWAS, amantadine therapy achieved EEG activity normalisation and seizure control (myoclonic and absence seizures) in 80% (4/5). Among the patients with refractory epilepsy, only one (14.2%) achieved seizure control (75–99% response). One patient (10%) developed adverse effects (irritability and insomnia), leading to withdrawal of amantadine.

ConclusionAmantadine is an effective and safe treatment for drug-resistant generalised epilepsy, especially in patients with D/EE-SWAS.

Estudios previos sugieren que la amantadina podría ser eficaz como fármaco antiepiléptico (FAC). En este estudio evaluamos su eficacia en niños con epilepsia generalizada refractaria.

MétodoEstudio retrospectivo de niños con encefalopatía epiléptica y del desarrollo con activación de punta-onda en sueño (DEE-SWAS) o epilepsia generalizada con ausencias refractarias tratados con amantadina en un hospital terciario durante un periodo de 3 años.

ResultadosSe analizaron 12 niños con una mediana de edad de 9,5 años (rango: 3-11 años) en los que se inició tratamiento con amantadina, con una mediana de duración desde el inicio de la enfermedad de 5 años (rango: 1-8 años). Antes de iniciar el tratamiento con amantadina, los pacientes habían recibido una media de 9,4 FAC (rango: 6-14), y 9 habían seguido una dieta cetogénica. Excepto en un paciente con lesión talámica, no presentaban lesión estructural en resonancia cerebral. Cinco fueron diagnosticados de DEE-SWAS, y 7 tenían epilepsia generalizada con ausencias refractarias, incluyendo: 5 con ausencia infantil refractaria, uno con epilepsia con mioclonías palpebrales y otro con síndrome de Lennox-Gastaut. La amantadina se añadió de forma coadyuvante a otros FAC (media: 2,7) a una dosis media de 5,6mg/kg/día, máxima de 300mg/día. En el grupo con DEE-SWAS el tratamiento con amantadina produjo la normalización del electroencefalograma y el control de las crisis (mioclónicas y de ausencia) en el 80% de los casos (4/5). Entre los participantes con ausencias refractarias, solo un paciente (14,2%) experimentó un control de las crisis (75-99% de respuesta). Un paciente (10%) desarrolló efectos adversos (irritabilidad e insomnio), por lo que se le retiró la amantadina.

ConclusionesLa amantadina puede ser un tratamiento eficaz y seguro para las epilepsias generalizadas farmacorresistentes, especialmente en los pacientes con DEE-SWAS.

Amantadine, a tricyclic amine with dopaminergic effects, is currently used for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Its effects result from enhanced dopamine release and dopamine reuptake inhibition, and in vivo studies have shown that amantadine directly upregulates D2 receptors. Amantadine was first used in 1976 for the treatment and prophylaxis of influenza A infection due to its ability to act on the transmembrane domain of the viral M2 protein, thereby preventing the release of viral RNA into the host cell. In recent years, the drug has been found to be effective not only in Parkinson's disease, but also in various behavioural disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, and unipolar depression, as well as acquired brain injury,1 probably due to its effects as a noncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist.2 Furthermore, several authors have hypothesised that amantadine also reduces microglia-associated inflammation.

The dopaminergic agonism, NMDA antagonism, and anti-inflammatory action of amantadine may explain its antiepileptic effects. These antiepileptic properties were discovered serendipitously when 2 children with epilepsy treated with amantadine for influenza infection presented seizure freedom. The authors of the original study later replicated these results and demonstrated the effectiveness of amantadine as an add-on therapy in 10 children with refractory generalised absence epilepsy and/or myoclonic seizures.3

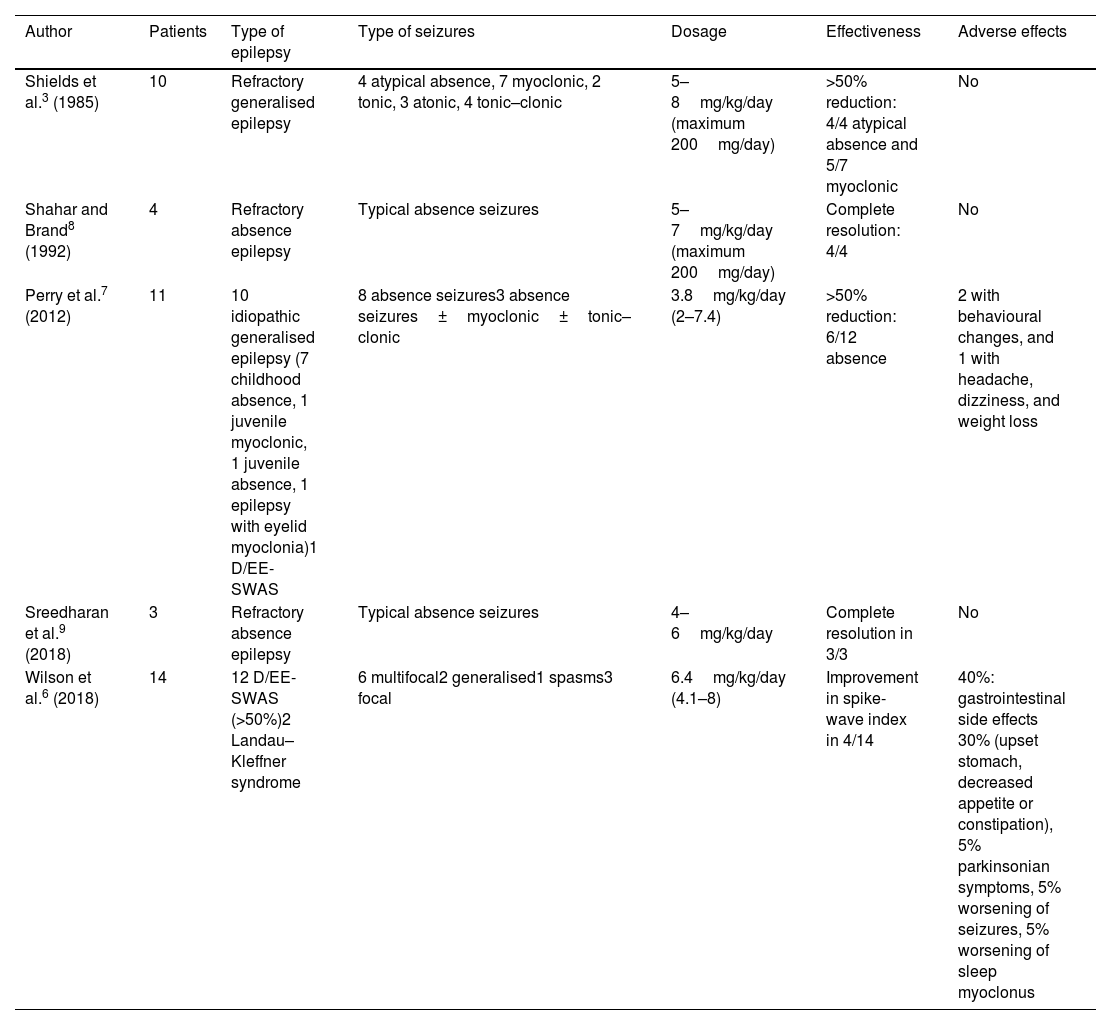

Since these first reports of the use of amantadine as an antiepileptic drug, only a few small case series or case reports have been published, and research on amantadine for the treatment of refractory absence seizures or developmental and/or epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation in sleep (D/EE-SWAS) is particularly scarce (Table 1). Absence seizures are sometimes refractory to anti-seizure medications (ASM). D/EE-SWAS is an epileptic syndrome in which the epileptic activity itself causes impaired psychomotor development, which underscores the need to explore new effective drugs. Our aim in this study is to describe the effectiveness of amantadine in children with these 2 types of drug-resistant generalised epilepsy.

Use of amantadine in epilepsy according to the literature.

| Author | Patients | Type of epilepsy | Type of seizures | Dosage | Effectiveness | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shields et al.3 (1985) | 10 | Refractory generalised epilepsy | 4 atypical absence, 7 myoclonic, 2 tonic, 3 atonic, 4 tonic–clonic | 5–8mg/kg/day (maximum 200mg/day) | >50% reduction: 4/4 atypical absence and 5/7 myoclonic | No |

| Shahar and Brand8 (1992) | 4 | Refractory absence epilepsy | Typical absence seizures | 5–7mg/kg/day (maximum 200mg/day) | Complete resolution: 4/4 | No |

| Perry et al.7 (2012) | 11 | 10 idiopathic generalised epilepsy (7 childhood absence, 1 juvenile myoclonic, 1 juvenile absence, 1 epilepsy with eyelid myoclonia)1 D/EE-SWAS | 8 absence seizures3 absence seizures±myoclonic±tonic–clonic | 3.8mg/kg/day (2–7.4) | >50% reduction: 6/12 absence | 2 with behavioural changes, and 1 with headache, dizziness, and weight loss |

| Sreedharan et al.9 (2018) | 3 | Refractory absence epilepsy | Typical absence seizures | 4–6mg/kg/day | Complete resolution in 3/3 | No |

| Wilson et al.6 (2018) | 14 | 12 D/EE-SWAS (>50%)2 Landau–Kleffner syndrome | 6 multifocal2 generalised1 spasms3 focal | 6.4mg/kg/day (4.1–8) | Improvement in spike-wave index in 4/14 | 40%: gastrointestinal side effects 30% (upset stomach, decreased appetite or constipation), 5% parkinsonian symptoms, 5% worsening of seizures, 5% worsening of sleep myoclonus |

D/EE-SWAS: developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation in sleep and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation.

Following approval of our protocol by the local research ethics committee, we reviewed the medical records of all patients younger than 18 years with D/EE-SWAS or epilepsy with refractory absence seizures who had been treated with amantadine in our hospital since January 2017. To be included, all patients were required to have completed follow-up as of April 2023.

The latest International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) classification defines D/EE-SWAS as a type of epileptic encephalopathy characterised by cognitive, behavioural, and motor regression associated with an EEG pattern of slow (1.5–2Hz) spike-and-wave activity that is markedly activated during non-rapid eye movement sleep.4 Previous treatment with corticosteroids and benzodiazepines was ineffective in all participants with D/EE-SWAS. The term refractory absence seizure refers to epilepsy with typically slow (2.5–4Hz), generalised spike-and-wave discharges that do not respond to first-line ASMs including valproic acid, ethosuximide, and lamotrigine.

At minimum, all patients underwent 1.5T brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical exome sequencing (including complete sequencing of the SLC2A1 gene in patients with early-onset refractory absence seizures). Patients with D/EE-SWAS underwent cognitive and behavioural assessment before and after treatment with amantadine, including intelligence (Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fifth edition or Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales, second edition), executive function and language (NEPSY-II battery; Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, second edition; Behaviour Rating Inventory of Executive Function, second edition), and behavioural (Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scales, third edition) tests.

Relevant clinical and demographic data were gathered from electronic medical records, including seizure and epilepsy type, main comorbidities, EEG findings, and results from other complementary tests, as well as treatments used and their efficacy. In the refractory epilepsy group, amantadine was considered effective when it achieved a >50% decrease in seizure frequency. In the D/EE-SWAS group, in addition to considering its impact on seizure frequency, amantadine was considered effective when the SWAS pattern disappeared.

All patients underwent an EEG study prior to administration of amantadine and 3 months after treatment onset.

Amantadine was initially titrated to a target dose ranging from 4mg/kg/day to 7.5mg/kg/day, to a maximum daily dose of 300mg.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 17.

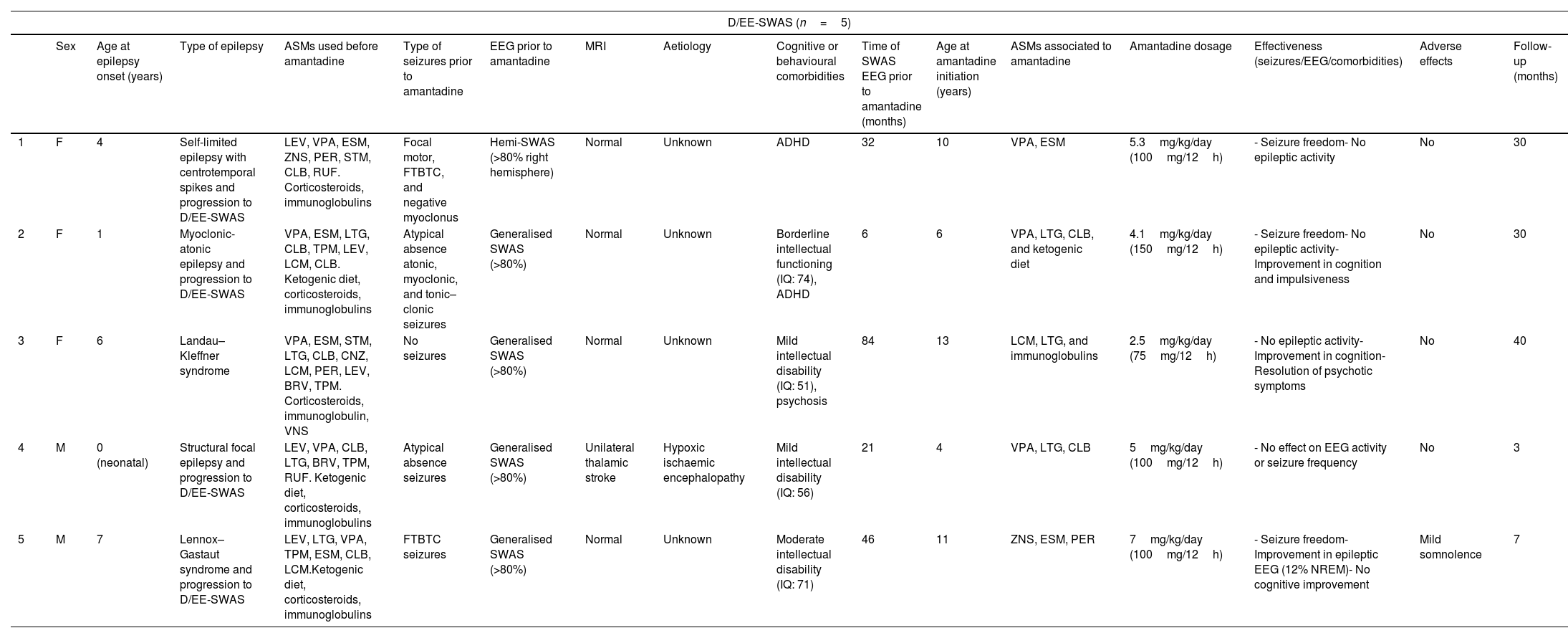

ResultsPatient characteristicsTwelve patients (5 girls and 7 boys) were treated with amantadine during the study period. Patient demographic characteristics and the effects of amantadine are summarised in Tables 2 and 3.

Patient characteristics and effects of amantadine.

| D/EE-SWAS (n=5) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age at epilepsy onset (years) | Type of epilepsy | ASMs used before amantadine | Type of seizures prior to amantadine | EEG prior to amantadine | MRI | Aetiology | Cognitive or behavioural comorbidities | Time of SWAS EEG prior to amantadine (months) | Age at amantadine initiation (years) | ASMs associated to amantadine | Amantadine dosage | Effectiveness (seizures/EEG/comorbidities) | Adverse effects | Follow-up (months) | |

| 1 | F | 4 | Self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes and progression to D/EE-SWAS | LEV, VPA, ESM, ZNS, PER, STM, CLB, RUF. Corticosteroids, immunoglobulins | Focal motor, FTBTC, and negative myoclonus | Hemi-SWAS (>80% right hemisphere) | Normal | Unknown | ADHD | 32 | 10 | VPA, ESM | 5.3mg/kg/day (100mg/12h) | - Seizure freedom- No epileptic activity | No | 30 |

| 2 | F | 1 | Myoclonic-atonic epilepsy and progression to D/EE-SWAS | VPA, ESM, LTG, CLB, TPM, LEV, LCM, CLB. Ketogenic diet, corticosteroids, immunoglobulins | Atypical absence atonic, myoclonic, and tonic–clonic seizures | Generalised SWAS (>80%) | Normal | Unknown | Borderline intellectual functioning (IQ: 74), ADHD | 6 | 6 | VPA, LTG, CLB, and ketogenic diet | 4.1mg/kg/day (150mg/12h) | - Seizure freedom- No epileptic activity- Improvement in cognition and impulsiveness | No | 30 |

| 3 | F | 6 | Landau–Kleffner syndrome | VPA, ESM, STM, LTG, CLB, CNZ, LCM, PER, LEV, BRV, TPM. Corticosteroids, immunoglobulin, VNS | No seizures | Generalised SWAS (>80%) | Normal | Unknown | Mild intellectual disability (IQ: 51), psychosis | 84 | 13 | LCM, LTG, and immunoglobulins | 2.5mg/kg/day (75mg/12h) | - No epileptic activity- Improvement in cognition- Resolution of psychotic symptoms | No | 40 |

| 4 | M | 0 (neonatal) | Structural focal epilepsy and progression to D/EE-SWAS | LEV, VPA, CLB, LTG, BRV, TPM, RUF. Ketogenic diet, corticosteroids, immunoglobulins | Atypical absence seizures | Generalised SWAS (>80%) | Unilateral thalamic stroke | Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy | Mild intellectual disability (IQ: 56) | 21 | 4 | VPA, LTG, CLB | 5mg/kg/day (100mg/12h) | - No effect on EEG activity or seizure frequency | No | 3 |

| 5 | M | 7 | Lennox–Gastaut syndrome and progression to D/EE-SWAS | LEV, LTG, VPA, TPM, ESM, CLB, LCM.Ketogenic diet, corticosteroids, immunoglobulins | FTBTC seizures | Generalised SWAS (>80%) | Normal | Unknown | Moderate intellectual disability (IQ: 71) | 46 | 11 | ZNS, ESM, PER | 7mg/kg/day (100mg/12h) | - Seizure freedom- Improvement in epileptic EEG (12% NREM)- No cognitive improvement | Mild somnolence | 7 |

| Refractory absence seizures (n=7) | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age of onset epilepsy (years) | Type of seizures | ASMs used before amantadine | Type of seizures prior to amantadine | EEG prior to amantadine | MRI | Aetiology | Cognitive or behavioural comorbidities | Age at amantadine initiation (years) | ASMs associated to amantadine | Amantadine dosage | Effectiveness (seizures/EEG/comorbidities) | Adverse effects | Follow-up (months) | |

| 6 | F | 1 | Typical absence seizures | LEV, VPA, ESM, LTG, ZNS, RUF, CLB. Ketogenic diet, corticosteroids, immunoglobulin | Absence and myoclonic seizures | 3–4Hz generalised spike-wave | Normal | Unknown | Mild intellectual disability (IQ 69), ADHD | 9 | VPA, LTG, RUF | 7.5mg/kg/day (50mg – 0 – 100mg) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | No | 6 |

| 7 | F | 4 | Typical absence seizures and eyelid myoclonia | BRV, LEV, VPA, ESM, LTG, CLB. Ketogenic diet | Absence seizures and eyelid myoclonia | Bilateral occipital spike-wave and photoparoxysmal EEG response | Normal | Unknown | Psychosis, ADHD | 13 | VPA, LTG | 4.5mg/kg/day (100mg/12h) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | No | 3 |

| 8 | M | 6 | Typical absence seizures | VPA, ESM, LTG, RUF, ZNS, CLB, CNZ, BRV. Ketogenic diet | Absence seizures | 3–4Hz generalised spike-wave | Normal | Unknown | Borderline intellectual functioning (IQ: 74), ADHD, eating disorder (anorexia nervosa) | 11 | VPA, ESM | 10mg/kg/day (75mg/8h) | >90% reduction in seizures | No | 36 |

| 9 | M | 3 | Typical absence seizures | PER, ZNS, TPM, VPA, LTG, ESM, LEV. Ketogenic diet | Absence seizures | 3Hz generalised polyspike-wave | Normal | Gaucher disease; homozygous mutations in GBA | Moderate intellectual disability (IQ: 49), ADHD | 6 | VPA, ESM | 4.7mg/kg/day (50mg/12h) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | Irritability, drowsiness, and insomnia | 3 |

| 10 | M | 2 | Typical absence seizures, myoclonic and tonic–clonic seizures | VPA, LEV, BRV, CLB, CNZ, PER, LCM, LTG, ESM, ZNS, RUF, CBD. Ketogenic diet, corticosteroids, immunoglobulins | Myoclonic, absence, and toni-clonic seizures | Multifocal epileptic activity. 2.5–3Hz generalised spike-wave | Neuroglial cyst | Suspected mitochondrial disease | Moderate intellectual disability (IQ: 67), ADHD | 3 | VPA, LTG, CBD, CLB | 7.5mg/kg/day (50mg – 0 –100mg) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | No | 3 |

| 11 | M | 3 | Typical absence seizures | VPA, ESM, LEV, CLB, LTG, vitamin B6 | Absence seizures | 3Hz generalised polyspike-wave | Normal | Unknown | ADHD | 7 | VPA, TPM | 5mg/kg/day (100mg/24h) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | No | 3 |

| 12 | M | 2 | Typical absence seizures and myoclonic seizures | VPA, CLB, LEV, LTG, RUF, ESM, ZNS, BRV.Ketogenic diet | Absence seizures | 3Hz generalised polyspike-wave | Cerebellar atrophy | Unknown | Mild intellectual disability (IQ: 78), ADHD | 12 | BRV, ESM, LTG | 5mg/kg/day (100mg – 0 – 150mg) | No improvement in seizures or EEG findings | Drowsiness | 4 |

ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASM: antiseizure medication; BRV: brivaracetam; CBD: cannabidiol; CLB: clobazam; CNZ: clonazepam; D/EE-SWAS: developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation in sleep and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation; EEG: electroencephalography; ESM: ethosuximide; F: female; FTBTC: focal to bilateral tonic–clonic; IQ: intelligence quotient; LEV: levetiracetam; LCM: lacosamide; LTG: lamotrigine; M: male; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PER: perampanel; RUF: rufinamide; STM: sultiame; SWAS: spike-and-wave activation in sleep; TPM: topiramate; VNS: vagus nerve stimulation; VPA: valproic acid; ZNS: zonisamide.

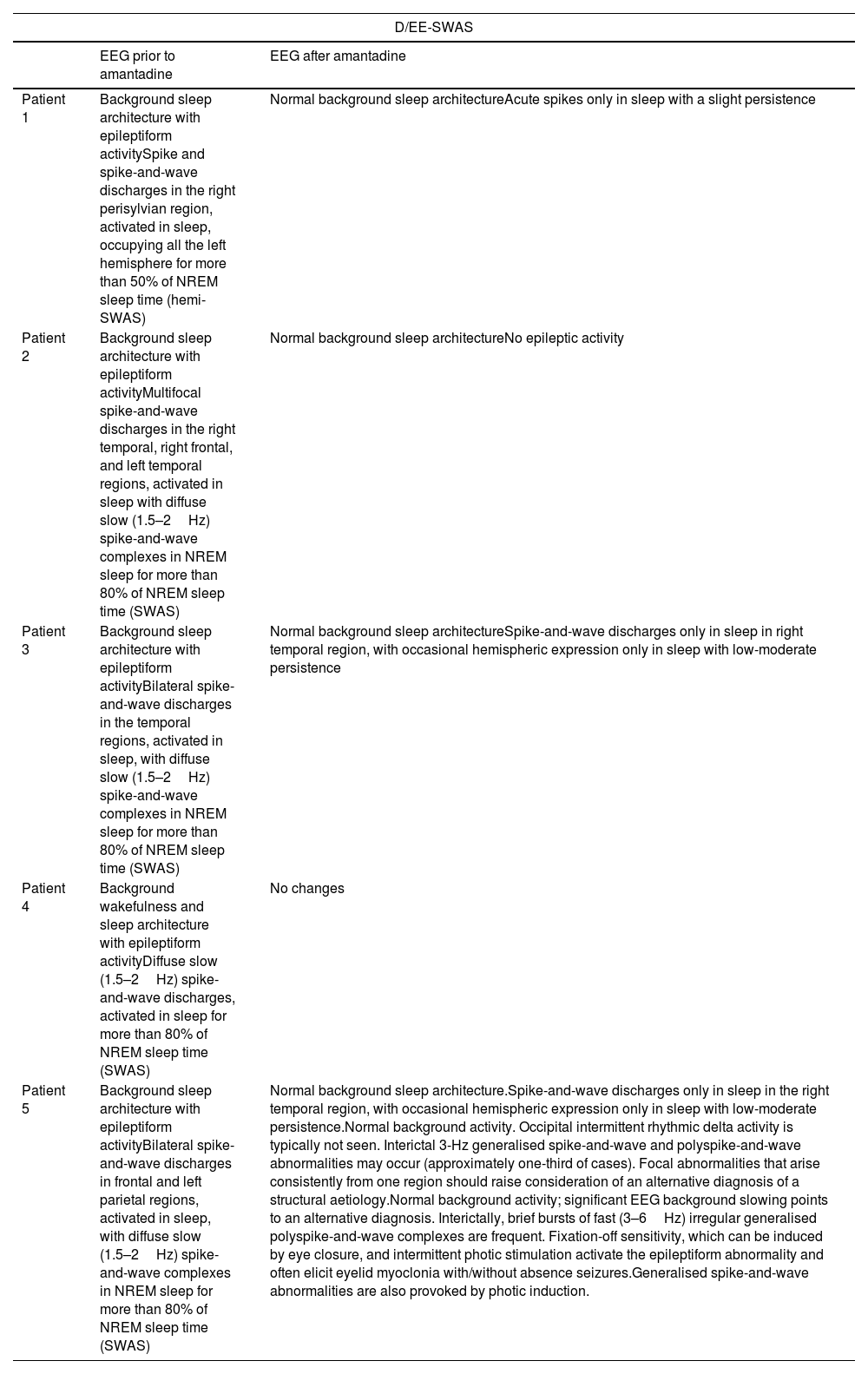

Patient characteristics and effects of amantadine.

| D/EE-SWAS | ||

|---|---|---|

| EEG prior to amantadine | EEG after amantadine | |

| Patient 1 | Background sleep architecture with epileptiform activitySpike and spike-and-wave discharges in the right perisylvian region, activated in sleep, occupying all the left hemisphere for more than 50% of NREM sleep time (hemi-SWAS) | Normal background sleep architectureAcute spikes only in sleep with a slight persistence |

| Patient 2 | Background sleep architecture with epileptiform activityMultifocal spike-and-wave discharges in the right temporal, right frontal, and left temporal regions, activated in sleep with diffuse slow (1.5–2Hz) spike-and-wave complexes in NREM sleep for more than 80% of NREM sleep time (SWAS) | Normal background sleep architectureNo epileptic activity |

| Patient 3 | Background sleep architecture with epileptiform activityBilateral spike-and-wave discharges in the temporal regions, activated in sleep, with diffuse slow (1.5–2Hz) spike-and-wave complexes in NREM sleep for more than 80% of NREM sleep time (SWAS) | Normal background sleep architectureSpike-and-wave discharges only in sleep in right temporal region, with occasional hemispheric expression only in sleep with low-moderate persistence |

| Patient 4 | Background wakefulness and sleep architecture with epileptiform activityDiffuse slow (1.5–2Hz) spike-and-wave discharges, activated in sleep for more than 80% of NREM sleep time (SWAS) | No changes |

| Patient 5 | Background sleep architecture with epileptiform activityBilateral spike-and-wave discharges in frontal and left parietal regions, activated in sleep, with diffuse slow (1.5–2Hz) spike-and-wave complexes in NREM sleep for more than 80% of NREM sleep time (SWAS) | Normal background sleep architecture.Spike-and-wave discharges only in sleep in the right temporal region, with occasional hemispheric expression only in sleep with low-moderate persistence.Normal background activity. Occipital intermittent rhythmic delta activity is typically not seen. Interictal 3-Hz generalised spike-and-wave and polyspike-and-wave abnormalities may occur (approximately one-third of cases). Focal abnormalities that arise consistently from one region should raise consideration of an alternative diagnosis of a structural aetiology.Normal background activity; significant EEG background slowing points to an alternative diagnosis. Interictally, brief bursts of fast (3–6Hz) irregular generalised polyspike-and-wave complexes are frequent. Fixation-off sensitivity, which can be induced by eye closure, and intermittent photic stimulation activate the epileptiform abnormality and often elicit eyelid myoclonia with/without absence seizures.Generalised spike-and-wave abnormalities are also provoked by photic induction. |

| Refractory absence seizures | ||

|---|---|---|

| EEG prior to amantadine | EEG after amantadine | |

| Patient 6 | Normal background sleep and wakefulness architectureGeneralised spike-wave discharges (3–4Hz), triggered by hyperventilationNo focal epileptic activityIctal: typical absence seizures recorded on video-EEG (3.5–4Hz) | No changesEEG shows the classical finding of generalised spike-wave discharges, typically 2.5–5.5Hz, which are often brought out during drowsiness, sleep, and on awakening. Discharges often appear fragmented during sleep and can have focal features. However, consistent focal epileptiform activity or focal slowing should not occur. A photoparoxysmal response occurs with intermittent photic stimulation in most untreated patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy and a minority of patients with childhood absence epilepsy and juvenile absence epilepsy; however, this may depend on the methodology of intermittent photic stimulation applied. Photosensitivity is also seen in specific genetic developmental and/or epileptic encephalopathies and occipital epilepsies. Hyperventilation often triggers generalised spike-wave discharges. Appropriate ASMs may abolish generalised spike-wave discharges at therapeutic dose. |

| Patient 7 | Normal background sleep and wakefulness architectureInterictal 3-Hz generalised spike-and-wave and polyspike-and-wave dischargesFixation-off sensitivity and photic induction activate the epileptiform abnormality and cause eyelid myoclonia without absences.No focal epileptic activityIctal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3Hz) | No changes |

| Patient 8 | Normal background sleep and wakefulness architectureGeneralised spike-wave discharges (3–3.5Hz), triggered by hyperventilationNo focal epileptic activityIctal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3–3.5Hz) | Normal background sleep and wakefulness architectureNo epileptic activity |

| Patient 9 | Slow background sleep and wakefulness architectureGeneralised spike-wave discharges (3–3.5Hz), triggered by hyperventilationBilateral frontal focal epileptic activity, slight persistence in wakefulnessIctal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3.3–5Hz) | No changes |

| Patient 10 | Slow background sleep and wakefulness architectureBilateral spike-and-wave and polyspike-and-wave discharges activated in sleep, triggered by hyperventilationBilateral focal epileptic activity in centrotemporal regionsIctal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3.3–5Hz) | No changes |

| Patient 11 | Slow background sleep and wakefulness architectureBilateral spike-and-wave discharges (3Hz)Ictal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3Hz) | No changes |

| Patient 12 | Background sleep architecture interfered by epileptiform activityGeneralised 3-Hz spike-and-wave complexes activated in sleep, triggered by hyperventilationIctal: typical absences recorded on video-EEG (3.3–5Hz). Myoclonic and tonic seizures were also recorded. | No changes |

ASM: antiseizure medication; D/EE-SWAS: developmental and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation in sleep and epileptic encephalopathy with spike-and-wave activation; EEG: electroencephalography; NREM: non-rapid eye movement.

Seven patients presented refractory absence seizures: 4 with early-onset absence seizures, one with eyelid myoclonia with absence seizures (epilepsy with eyelid myoclonia), one with an unclassified developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, and one with associated myoclonic seizures. Brain MRI studies showed cerebellar atrophy in one patient, but normal findings in the rest. A clear underlying aetiology was found in 2 patients, patients 4 and 9, who had Gaucher disease (homozygous GBA variant); the aetiological study was inconclusive for the remaining patients. Four patients had mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychiatric comorbidities included attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (6/7) and psychosis (1/7).

Of the 5 patients with D/EE-SWAS (3 with EE-SWAS and 2 with DEE-SWAS), one had Landau–Kleffner syndrome, one had progressed from self-limited epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes, one from Doose syndrome, one from Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, and one had history of perinatal thalamic stroke. One patient had hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (left thalamic lesion with focal atrophy and residual red cells in blood components, probably related to sequelae of perinatal ischaemic injury, without evidence of other brain or cerebellar alterations), and findings from the remaining MRI scans were normal. Cognitive impairment was frequent in the D/EE-SWAS group: 2 had mild intellectual disability (ID) and 2 had moderate ID, and all presented symptoms of ADHD.

Effectiveness of amantadine in patients with D/EE-SWASThe median age of seizure/epilepsy onset in patients with D/EE-SWAS was 4 years (range, 0–7). At the time amantadine was added to the treatment regimen, EEG recordings revealed generalised electrical activity during slow-wave sleep in 4 patients, while one patient had a continuous spike-and-wave pattern restricted to one hemisphere. Four patients had seizures (positive and negative myoclonic, focal motor, atypical absence, and tonic–clonic seizures). Onset of electrical status epilepticus in sleep (ESES) occurred a mean of 37.8 months before initiation of amantadine therapy (range, 6–84). Corticosteroids had been ineffective, and patients had received a mean of 9.6 ASMs (range, 8–11). Three patients had been prescribed a ketogenic diet and one had been undergone with vagus nerve stimulator implantation. The median dose of amantadine was 5mg/kg/day (range, 2.5–7), with a maximum dose of 300mg/day, with doses administered every 12 or 24h.

At 3 months of treatment, a clear response was observed in 80% of the participants, with patients exhibiting complete seizure control and normal or nearly normal EEG recordings. The median duration of follow-up among responders was 27 months (range, 7–36).

Effectiveness of amantadine in patients with refractory absence seizuresThe median age at epilepsy onset was 3 years (range, 1–6). In addition to absence seizures, 3 patients presented another type of generalised seizures, including myoclonic (n=3) and tonic–clonic seizures (n=2). Epilepsy onset had occurred a mean of 5.7 years (range, 1–10) before the onset of amantadine as an add-on therapy. Patients with refractory absence seizures had received a median of 9.6 ASMs (range, 8–11), and the ketogenic diet had been ineffective in all cases. The median dose of amantadine was 6.3mg/kg/day (range, 4.5–10), with a maximum dose of 250mg/day, with doses administered every 8, 12, or 24h.

Only one patient with absence seizures (14.3%) responded well to therapy, achieving a 75–99% reduction in seizure frequency. This effect was maintained for 3 years, after which seizure frequency returned to previous levels. Amantadine was ineffective for non-absence seizures in all patients.

Adverse effectsAmantadine was well tolerated in our cohort. Only one patient had to discontinue the medication, due to insomnia, irritability, nausea, and vomiting. None of the remaining patients reported adverse effects.

DiscussionThere is limited evidence of the effectiveness of amantadine as an add-on therapy in refractory generalised epilepsies.3,5–9 We observed good response in 41.7% of the cohort. This rate is especially high considering the inclusion of patients with D/EE-SWAS, a type of epilepsy that is frequently treatment-resistant.

Amantadine improved EEG activity in 4 of the 5 participants with D/EE-SWAS. The only other published study on the effectiveness of amantadine in children with D/EE-SWAS reported a reduction in the median baseline spike-wave index in 20 patients (76% vs 53%; P=.01), while 53% of patients exhibited improvements in EEG recordings and 30% achieved complete resolution of continuous spike-and-wave activity during non-REM sleep.7 The more modest improvement reported in that study may be explained by the greater heterogeneity and the fact that not all participants had D/EE-SWAS; in fact, 6 patients had autistic regression with epileptiform anomalies but without epilepsy.7 Other studies of amantadine for refractory absence seizures have included patients with D/EE-SWAS, although the authors do not specify treatment effectiveness by disease subtype.7,10 In our sample, the only patient for whom amantadine was ineffective in treating D/EE-SWAS had perinatal hypoxic-ischaemic thalamic injury, a structural brain abnormality. In this type of epilepsy, medical treatment is often ineffective, and surgery is frequently required.

Unlike in the D/EE-SWAS group, amantadine was only effective in one of the 7 patients with refractory absence seizures (14.3%). These results stand in contrast against those of other studies, such as the study by Shahar and Brand,8 who administered amantadine to 4 children with refractory absence epilepsy, rapidly achieving seizure freedom and normalisation of EEG readings in all cases; these effects persisted for 24–36 months. This difference in treatment effectiveness may be due to the fact that the series reported by Shahar and Brand included patients with less refractory disease (median of 2.75 ASMs before the introduction of amantadine, vs 9.6 in our patients). Additionally, therapy with phenytoin had failed in 2 patients from that study, and none had received lamotrigine. As ethosuximide, lamotrigine, and valproic acid are first-line treatments for absence seizures,11 this could explain the differences between our results and those of the study by Sreedharan et al.,9 who reported seizure freedom after amantadine initiation in 4 children with refractory absence epilepsy, none of whom had taken ethosuximide. Perry et al.7 observed a reduction in seizure frequency of over 90% within 3 months of starting amantadine in 6 of 12 children with refractory absence epilepsy. This decrease was more pronounced than that observed in our study, although seizure frequency data were based on parent reports exclusively, a method with inherent limitations.

The exact action mechanism of amantadine remains unknown. The drug acts as a dopamine agonist, or by blocking the excitatory NMDA receptors in the thalamocortical circuits. NMDA receptor antagonism may explain the effectiveness of amantadine in patients with GRIN2A, GRIN2B, and GRIN2D gain-of-function mutations,12,13 although genetic studies revealed that none of our patients had GRINpathies. Other noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonists, such as memantine, are used for their antiepileptic properties. Recently, Schiller et al.14 published a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in 27 patients aged 6 to 18 years with epileptic encephalopathies, reporting greater effectiveness for epilepsy than placebo (33% vs 7%; P<.04) and improvements in ADHD and autism symptoms. Cases have also been reported of positive response to memantine in children with epilepsy caused by pathogenic variants in genes encoding NMDA receptor subunits and whose symptoms are refractory to conventional ASMs.15

The most effective treatments for children with D/EE-SWAS are corticosteroids and benzodiazepines, although these therapies are poorly tolerated over the long term. When administered to patients with D/EE-SWAS, amantadine causes few adverse reactions and has a sustained treatment effect, making it an attractive option.

ConclusionAmantadine represents an effective, safe treatment for refractory generalised epilepsy in children, especially those with D/EE-SWAS, whereas it appears to be less effective for patients with refractory absence seizures.

Authors’ contributionsThe first and second authors designed the work, reviewed and analysed the results, and drafted the article.

The remaining neurologists reviewed the article and contributed to the intellectual content of the discussion.

The participating neurophysiologists reviewed the EEG recordings of the patients.

The neuropsychologist reviewed the neuropsychological histories of the patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.