This study aimed to investigate the interrelationship between sleep disturbances, heart rate variability (HRV), and the risk of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), with a focus on identifying novel risk factors related to sleep and autonomic function.

MethodsPatients with epilepsy undergoing overnight video-electroencephalographic monitoring were recruited between December 2020 and June 2022. Seizure-related characteristics were collected. Subjective and objective sleep quality were assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), duration of the first and longest cycle of the whole night's sleep (cycle 1 duration), sleep latency, and number of arousals from lights-off to the start of cycle 1 (AR number). Autonomic function was evaluated using HRV parameters, including root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) and the percentage of NN50 intervals (PNN50), during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stages 2 and 3. The risk of SUDEP was measured using the 7-item SUDEP inventory (SUDEP-7).

ResultsA total of 127 patients with epilepsy were included in the study. Patients with a cycle 1 duration of less than 60min had significantly higher PSQI scores (t test, P<.05) compared to those with a cycle 1 duration of 60min or more, consistent with poorer subjective sleep quality. Daytime dysfunction (reflected in the 7th domain of the PSQI) and RMSSD and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3 (one of the HRV time domain parameters) were both independent risk factors for SUDEP. Although no positive mediation effect of HRV on daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk was observed, an inverse relationship between RMSSD during NREM stage 3 and both outcomes was identified.

ConclusionPatients with epilepsy (and especially those with generalised tonic–clonic seizures) exhibiting daytime dysfunction should be prioritised for SUDEP risk screening. Further research should explore additional factors beyond HRV and potential interventions targeting sleep and autonomic function in patients with epilepsy.

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo investigar la interrelación entre las alteraciones del sueño, la variabilidad de la frecuencia cardíaca (VFC) y el riesgo de muerte súbita inesperada en la epilepsia (SUDEP), centrándose en identificar nuevos factores de riesgo relacionados con el sueño y la función autónoma.

MétodosSe reclutaron pacientes con epilepsia que se sometieron a un monitoreo video-electroencefalográfico durante la noche entre diciembre de 2020 y junio de 2022. Se recopilaron características relacionadas con las convulsiones. La calidad del sueño subjetiva y objetiva se evaluó utilizando el índice de calidad del sueño de Pittsburgh (PSQI), la escala de somnolencia de Epworth (ESS), la duración del primer y el ciclo más largo de toda la noche de sueño (duración del Ciclo 1), la latencia del sueño y el número de despertares desde que se apagaron las luces hasta el inicio del Ciclo 1 (número de AR). La función autónoma se evaluó utilizando parámetros de VFC, incluyendo RMSSD y PNN50, durante las etapas 2 y 3 del sueño NREM. El riesgo de SUDEP se midió utilizando el inventario de 7 ítems de SUDEP (SUDEP-7).

ResultadosUn total de 127 pacientes con epilepsia fueron incluidos en el estudio. Los pacientes con una duración del Ciclo 1 de menos de 60min presentaron puntuaciones de PSQI significativamente más altas (prueba t, p<0,05) en comparación con aquellos con una duración del Ciclo 1 de 60min o más, lo que es consistente con una peor calidad subjetiva del sueño. La disfunción diurna (reflejada en el séptimo dominio del PSQI) y RMSSD y PNN50 durante la etapa 3 del sueño NREM (uno de los parámetros de dominio temporal de la VFC) fueron factores de riesgo independientes para el SUDEP. Aunque no se observó un efecto de mediación positivo de la VFC sobre la disfunción diurna y el riesgo de SUDEP, se identificó una relación inversa entre RMSSD durante la etapa 3 del NREM y ambos resultados.

ConclusiónLos pacientes con epilepsia (especialmente aquellos con GTCS) que exhiben disfunción diurna deben ser priorizados para el cribado del riesgo de SUDEP. Se debe investigar más a fondo factores adicionales más allá de la VFC y posibles intervenciones dirigidas al sueño y a la función autónoma en los pacientes con epilepsia.

Sleep disturbances are highly prevalent among patients with epilepsy.1,2 Research indicates that epileptiform discharges follow a 24-h periodic pattern, peaking during nocturnal hours.3 These discharges, alongside frequent seizures, disrupt sleep architecture, leading to increased awakenings and fragmented sleep.4 Importantly, a significant proportion of cases of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) occur during sleep, particularly among individuals with generalised tonic–clonic seizures, indicating that disrupted sleep may be a risk factor for SUDEP.5

Autonomic dysfunction and arrhythmias have been proposed as key mechanisms associated with SUDEP.6 Heart rate variability (HRV), which reflects the variation in RR intervals on electrocardiography (ECG), is a commonly used marker of autonomic nervous system activity.7 Several studies have identified abnormalities in HRV parameters such as the standard deviation of NN intervals (SDNN), root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), and low-frequency (LF) and high-frequency (HF) power in patients with epilepsy.8 A 2023 meta-analysis by Evangelista et al.9 found altered HRV parameters in 72 cases of SUDEP, reinforcing the hypothesis that autonomic dysfunction plays a role in SUDEP risk.

Impaired sleep quality also affects HRV, as both rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) sleep stages modulate the LF/HF ratio, a marker of sympatho-vagal balance; for instance, sleep deprivation has been shown to increase HF power and disrupt autonomic homeostasis.10 However, it remains unclear whether HRV mediates the effects of sleep disturbances on SUDEP risk.

In this study, we aimed to address this gap by investigating the potential mediating role of HRV in the relationship between sleep disturbances and SUDEP risk. Using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the 7-item SUDEP inventory (SUDEP-7), and overnight video-electroencephalography (vEEG) monitoring (incorporating both EEG and ECG channels), we explored correlations between sleep profiles, HRV parameters, and SUDEP risk. Our objective was to elucidate the interactive relationships between sleep disturbances, autonomic dysfunction, and the risk of SUDEP.

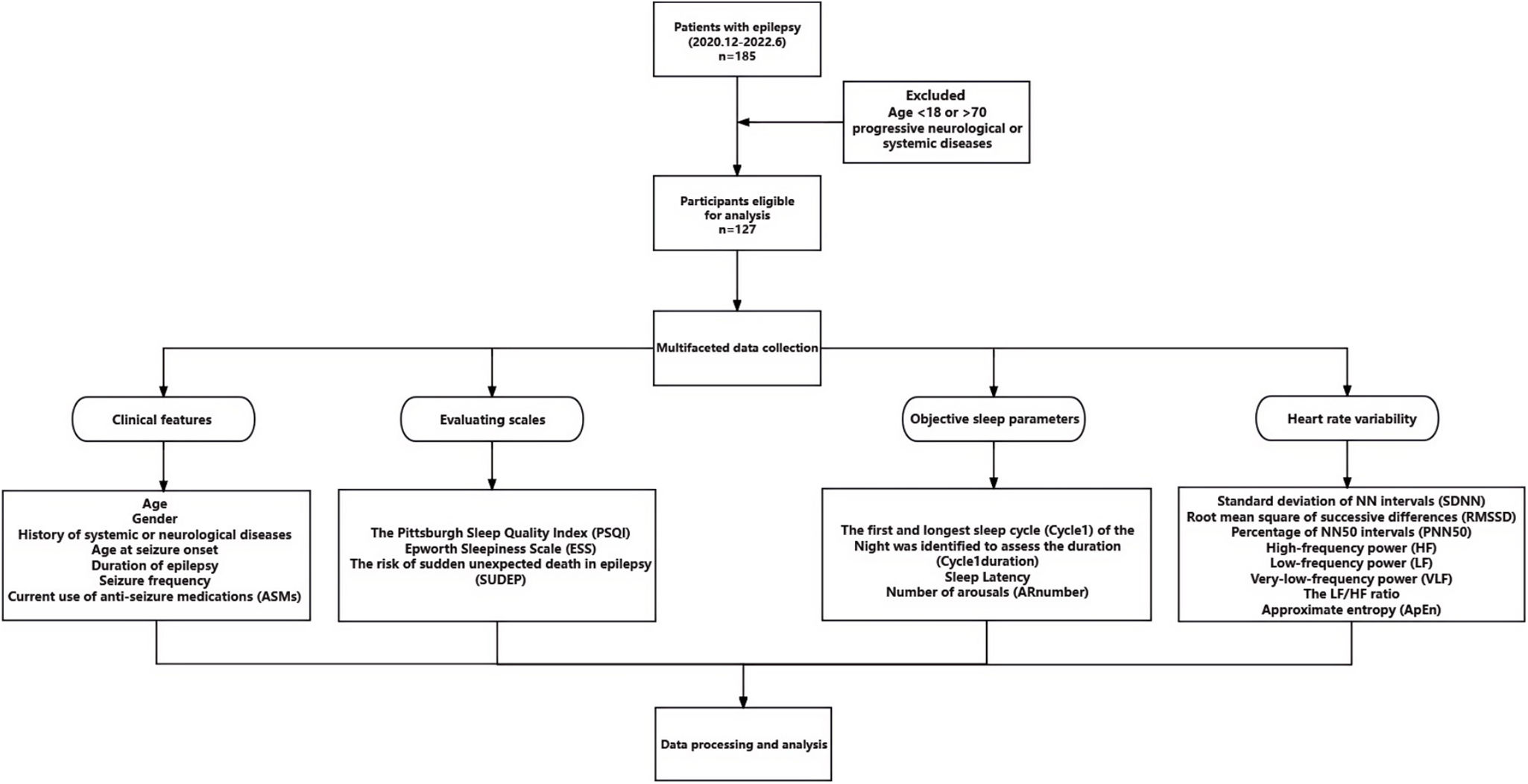

Material and methodsStudy designThis was a single-centre observational study conducted at Zhongshan Hospital Xiamen Branch between December 2020 and June 2022. The study included patients undergoing overnight vEEG monitoring for the diagnosis of epilepsy. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital Xiamen Branch (approval ID: B2022-023), and all participants provided written informed consent. The study flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Study flowchart. ApEn: approximate entrophy; AR number: number of arousals; ASM: anti-seizure medication; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; HF: high-frequency power; LF: low-frequency power; PNN50: percentage of NN50 intervals; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; RMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SDNN: standard deviation of NN intervals; SUDEP-7: Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy Risk Assessment; VLF: very-low-frequency power.

We screened and included patients aged 18–70 years of both sexes who met the 2014 International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) diagnostic criteria for epilepsy.1 We excluded participants with progressive neurological or systemic diseases, including malignant tumours, and those who did not complete the sleep questionnaires at the time of vEEG recording. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies were conducted for all participants to investigate structural aetiologies of epilepsy. No specific instructions were given regarding sleep deprivation before vEEG recording.

Clinical features of included patients with epilepsyDemographic and clinical information was collected from all participants, including age, sex, history of systemic or neurological diseases, age at seizure onset, duration of epilepsy, seizure frequency, and current use of anti-seizure medications (ASM). Epilepsy classification and aetiology were determined using clinical, imaging, and EEG data.

Sleep quality and SUDEP-7 risk assessmentPrior to vEEG monitoring, patients were instructed to complete 2 validated sleep assessment tools: the PSQI to assess sleep quality and the ESS to measure daytime sleepiness.11 The PSQI includes 7 domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medications, and daytime dysfunction.12 A score≥1 in the PSQI's 7th domain (daytime dysfunction) was used to identify patients with daytime sleepiness or other functional impairments in daily life.

The SUDEP-7 inventory, which evaluates the risk of SUDEP, was administered to all participants. The 7 items assessed in the SUDEP-7 are: (1) >3 tonic–clonic seizures in the past year; (2) ≥1 tonic–clonic seizure in the past year; (3) ≥1 seizure of any type over the past 12 months; (4) >50 seizures per month over the past 12 months; (5) epilepsy duration≥30 years; (6) current use of 3 or more ASMs; and (7) developmental intellectual disability or intelligence quotient (IQ)<70.13

EEG recording and sleep profilesEEG data were acquired using the Nihon Kohden EEG system, with 25-channel long-term EEG recording according to the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology (IFCN) recommendations.14 A single-channel ECG recorded heart rate. All signals were digitised at a 1000-Hz sampling rate. The first and longest sleep cycle of the night (cycle 1) was identified to assess the duration (cycle 1 duration), sleep latency, and number of arousals (AR number) from lights-off to the start of cycle 1. Cycle 1 was defined by the collapse of α rhythm and the appearance of θ rhythm, while the end was marked by an arousal lasting ≥15s. Arousal was defined as an abrupt shift in EEG frequency, including α rhythm and/or frequencies>16Hz, lasting≥3 but <15s, preceded by ≥10s of sleep.15 EEG data were reviewed and scored by 2 independent raters (ZS and WP) to ensure accuracy and reliability.

Heart rate variability analysisHRV was assessed using 5-min EEG epochs with and without interictal epileptiform discharges (IED) from NREM sleep stages 2 and 3. If no IEDs were observed, only epochs from these sleep stages were used. Comparisons of HRV parameters between epochs with and without IEDs revealed no significant differences; thus, both types of epochs were included in the final analysis for patients with IEDs.

HRV parameters were assessed using power spectral analysis, including SDNN, RMSSD, percentage of NN50 intervals (PNN50), HF, LF, very-low-frequency power (VLF), the LF/HF ratio, and approximate entropy (ApEn) to evaluate the irregularity and complexity of RR intervals. The ECOMB software (developed by Jiatong Li) was used for HRV analysis, utilising Fourier transformation algorithms implemented in Python to convert ECG signals from EEG epochs into numerical data for further processing.

Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (standard deviation [SD]), and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages (n [%]). The serial mean interpolation method was used to handle missing data. Statistical significance was set at P<.05 for all analyses.

Normality tests (Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests) were conducted, and group comparisons were made using the independent t test and Chi-square test if the data were normally distributed, or otherwise with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess relationships between sleep profiles, HRV parameters, and SUDEP-7 scores. A stepwise linear regression model was applied to identify risk factors associated with SUDEP-7 scores.

Mediation analysis: To assess the potential mediating role of HRV parameters in the relationship between daytime dysfunction (PSQI daytime dysfunction) and SUDEP-7 scores, we employed the SPSS PROCESS macro (version 4.0), which utilises bootstrapping techniques for hypothesis testing. Harman's single-factor test was used to verify that common method bias was not present, as the first principal component accounted for 25.40% of the variance, below the critical 40% threshold. Bias-corrected bootstrapping with 5000 resamples was used to generate 95% confidence intervals for direct and indirect effects.

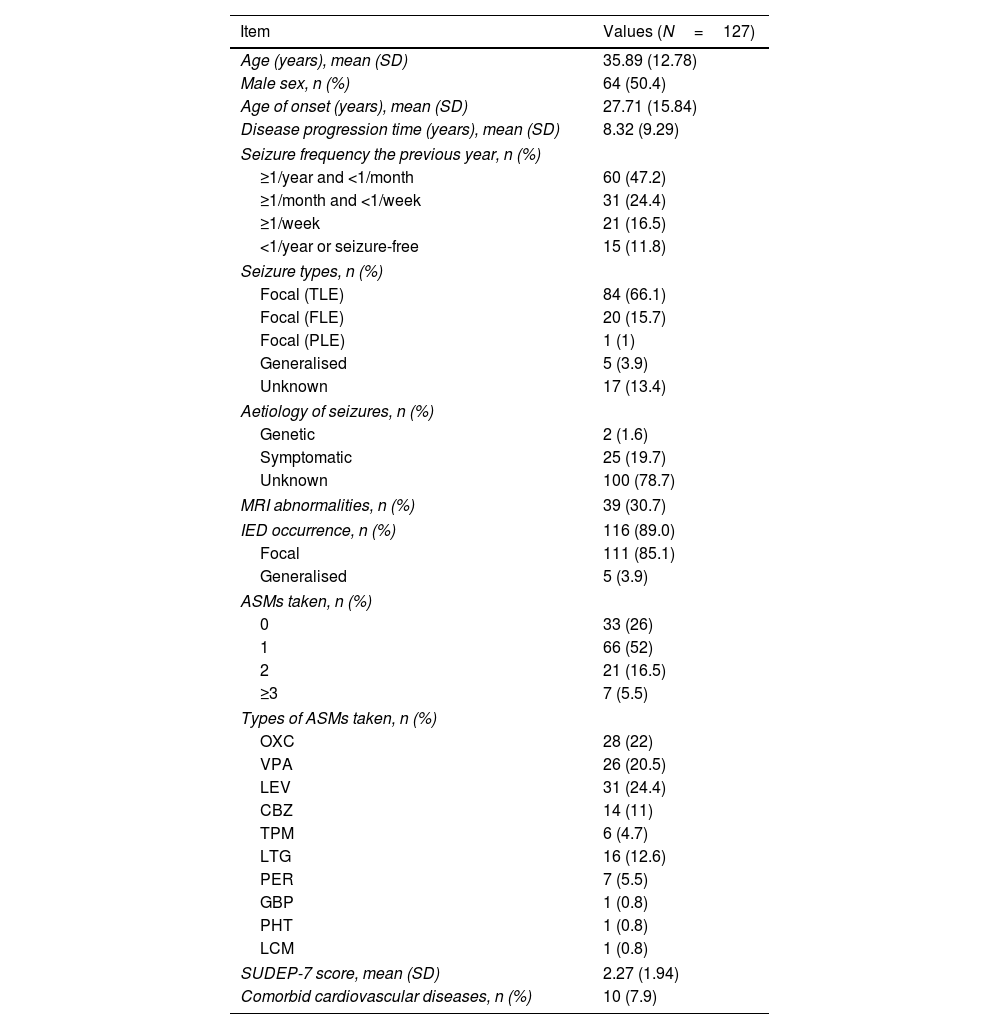

ResultsDemographic and clinical features of patients with epilepsyA total of 127 patients with epilepsy were included in the analysis after application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Table 1 summarises the demographic data, seizure-related characteristics, MRI abnormalities, the occurrence of IEDs, and the number and types of ASMs. Notably, 28 patients were not taking ASMs during EEG monitoring. Of these, 15 had newly diagnosed epilepsy, 2 were using traditional Chinese medicine, and 11 had poor medication compliance. All included patients underwent comprehensive comorbidity screening. No patient's medical records mentioned self-reported sleep apnoea. Ten patients had concomitant cardiovascular diseases: arterial hypertension in 8, history of myocarditis in one, and sinus bradycardia in 1.

Demographic and clinical features of our sample of patients with epilepsy.

| Item | Values (N=127) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 35.89 (12.78) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 64 (50.4) |

| Age of onset (years), mean (SD) | 27.71 (15.84) |

| Disease progression time (years), mean (SD) | 8.32 (9.29) |

| Seizure frequency the previous year, n (%) | |

| ≥1/year and <1/month | 60 (47.2) |

| ≥1/month and <1/week | 31 (24.4) |

| ≥1/week | 21 (16.5) |

| <1/year or seizure-free | 15 (11.8) |

| Seizure types, n (%) | |

| Focal (TLE) | 84 (66.1) |

| Focal (FLE) | 20 (15.7) |

| Focal (PLE) | 1 (1) |

| Generalised | 5 (3.9) |

| Unknown | 17 (13.4) |

| Aetiology of seizures, n (%) | |

| Genetic | 2 (1.6) |

| Symptomatic | 25 (19.7) |

| Unknown | 100 (78.7) |

| MRI abnormalities, n (%) | 39 (30.7) |

| IED occurrence, n (%) | 116 (89.0) |

| Focal | 111 (85.1) |

| Generalised | 5 (3.9) |

| ASMs taken, n (%) | |

| 0 | 33 (26) |

| 1 | 66 (52) |

| 2 | 21 (16.5) |

| ≥3 | 7 (5.5) |

| Types of ASMs taken, n (%) | |

| OXC | 28 (22) |

| VPA | 26 (20.5) |

| LEV | 31 (24.4) |

| CBZ | 14 (11) |

| TPM | 6 (4.7) |

| LTG | 16 (12.6) |

| PER | 7 (5.5) |

| GBP | 1 (0.8) |

| PHT | 1 (0.8) |

| LCM | 1 (0.8) |

| SUDEP-7 score, mean (SD) | 2.27 (1.94) |

| Comorbid cardiovascular diseases, n (%) | 10 (7.9) |

ASM: anti-seizure medication; CBZ: carbamazepine; FLE: frontal lobe epilepsy; GBP: gabapentin; IED: interictal epileptiform discharge; LCM: lacosamide; LEV: levetiracetam; LTG: lamotrigine; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; OXC: oxcarbazepine; PER: perampanel; PHT: phenytoin; PLE: parietal lobe epilepsy; SD: standard deviation; SUDEP-7: 7-item Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy Risk Inventory; TLE: temporal lobe epilepsy; TPM: topiramate; VPA: valproate.

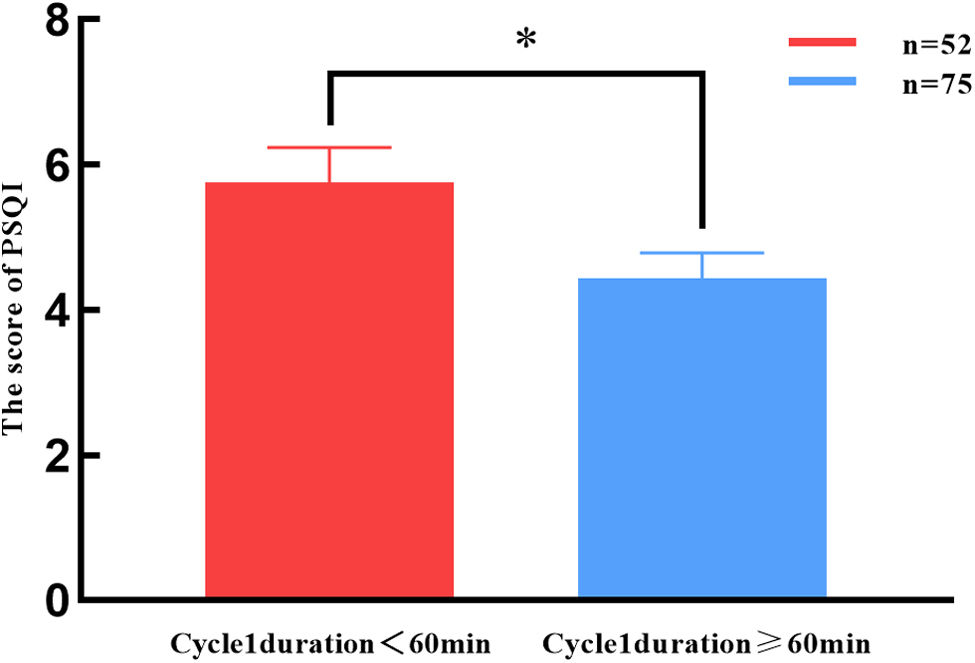

Subjective sleep quality was assessed using the PSQI and the ESS. Using a PSQI cut-off score of 5, which provides 89.6% sensitivity and 86.5% specificity in distinguishing good and poor sleepers,11,16 43 patients (33.9%) were classified as having poor sleep quality. Objective sleep quality was evaluated by analysing cycle 1 duration, sleep latency, and the number of arousals between lights-off and the start of cycle 1. The mean cycle 1 duration was 51.60 (5.82)min. Based on normal sleep cycle duration (60–90min), patients were divided into 2 groups: those with a cycle 1 duration≥60min and those with <60min. Fifty-two patients (40.9%) had a cycle 1 duration of <60min. As shown in Fig. 2, patients with a cycle 1 duration<60min had significantly higher PSQI scores, indicating poorer sleep quality (P=.026).

Comparison of PSQI scores as a function of cycle 1 duration. PSQI score was significantly higher in patients with a cycle 1 duration of less than 60min, compared to those with a cycle 1 duration of 60min or more. *P<.05). PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; cycle 1 duration: duration of the first and longest cycle of the whole night's sleep.

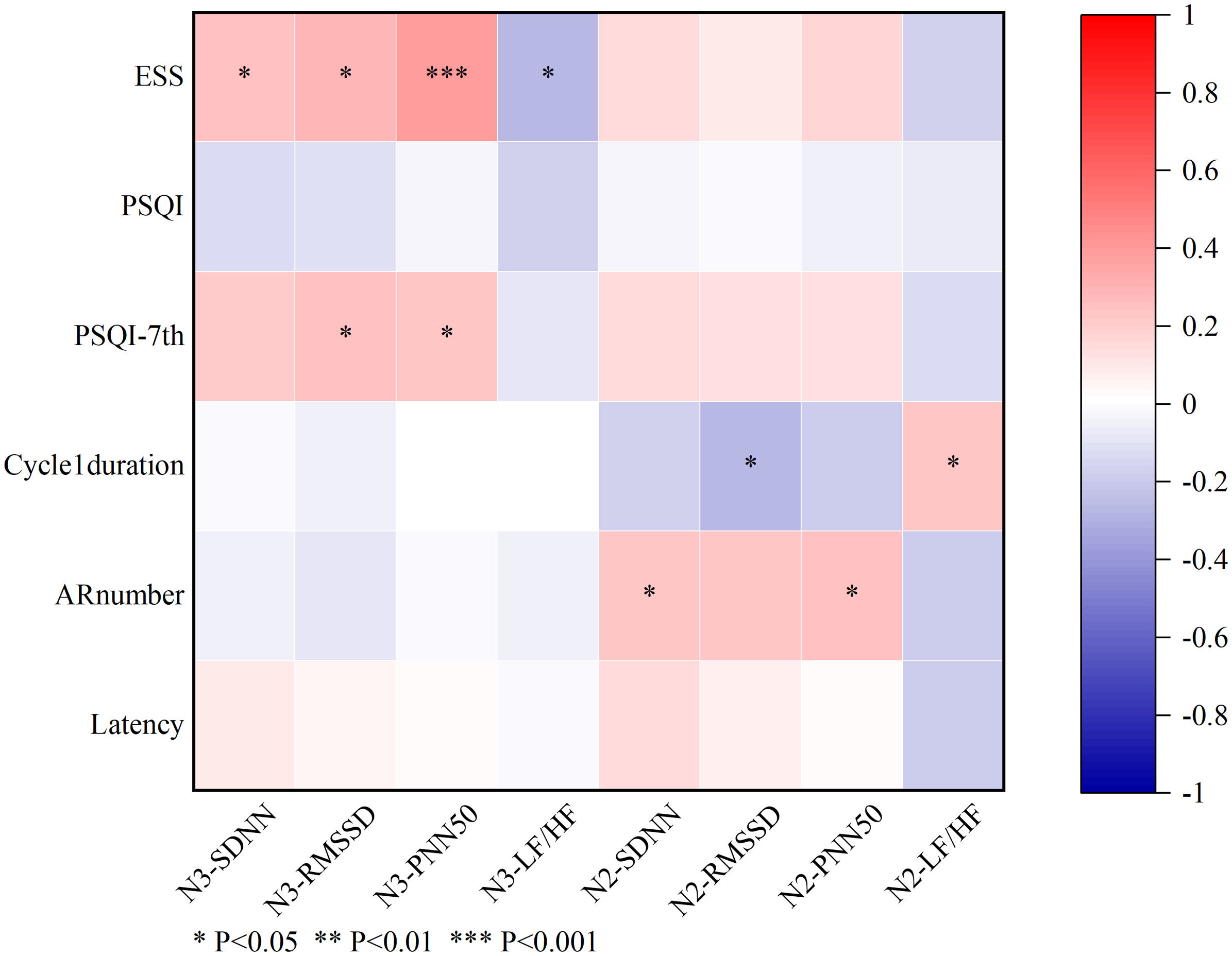

Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses were conducted to explore the relationships between HRV parameters and sleep profiles. The ESS score was positively correlated with several HRV parameters, including SDNN (r=0.241, P=.033), RMSSD (r=0.289, P=.010), and PNN50 (r=0.395, P<.001) during NREM sleep stage 3. Cycle 1 duration was negatively correlated with RMSSD (r=−0.271, P=.014) and positively correlated with LF/HF ratio (r=0.235, P=0.035) during NREM sleep stage 2. Additionally, AR number correlated positively with SDNN (r=0.238, P=.037) and PNN50 (r=0.248, P=.029) during NREM sleep stage 2.

Although there was no significant correlation between the total PSQI score and HRV parameters, a positive correlation was found between the PSQI's 7th domain (representing daytime dysfunction) and RMSSD (r=0.249, P=.028) and PNN50 (r=0.224, P=.049) during NREM sleep stage 3, mirroring the results for ESS and HRV (see Fig. 3).

Analysis of correlations between sleep-related parameters and heart rate variability parameters. The total ESS score correlated positively with SDNN, RMSSD, and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3. Cycle 1 duration showed a negative correlation with RMSSD and a positive correlation with the LF/HF ratio during NREM sleep stage 2. Additionally, AR number correlated positively with SDNN and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 2. No significant correlations were found between the total PSQI score and HRV parameters; however, the PSQI daytime dysfunction domain (PSQI-DD) correlated positively with RMSSD and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3. Spearman correlation analysis, 1=PSQI-DD≥1, n=95; 0=PSQI-DD<1, n=32. *P<.05, **P<.01, ***P<.001. N3-SDNN: SDNN during NREM sleep stage 3; N3-RMSSD: RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3; N3-PNN50: PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3; N3-LF/HF: LF/HF ratio during NREM sleep stage 3; N2-SDNN: SDNN during NREM sleep stage 2; N2-RMSSD: RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 2; N2-PNN50: PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 2; N2-LF/HF: LF/HF ratio during NREM sleep stage 2; AR number: number of arousals before cycle 1; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; LF/HF: low-frequency/high frequency ratio; PNN50: percentage of NN50 intervals; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PSQI-DD: PSQI daytime dysfunction domain; RMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SDNN: standard deviation of NN intervals.

No significant correlation was found between the total PSQI score and SUDEP-7 scores. However, a positive correlation was observed between the PSQI's 7th domain (daytime dysfunction) and SUDEP-7 score (Spearman correlation, r=0.193, P=.029). In addition, Pearson correlation analysis showed a negative correlation between SUDEP-7 scores (especially patients with generalised tonic–clonic seizures in the past 12 months) and time-domain HRV parameters, including RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 (r=−0.239, P=.035), as well as RMSSD (r=−0.251, P=.024) and PNN50 (r=−0.250, P=.025) during NREM sleep stage 2.

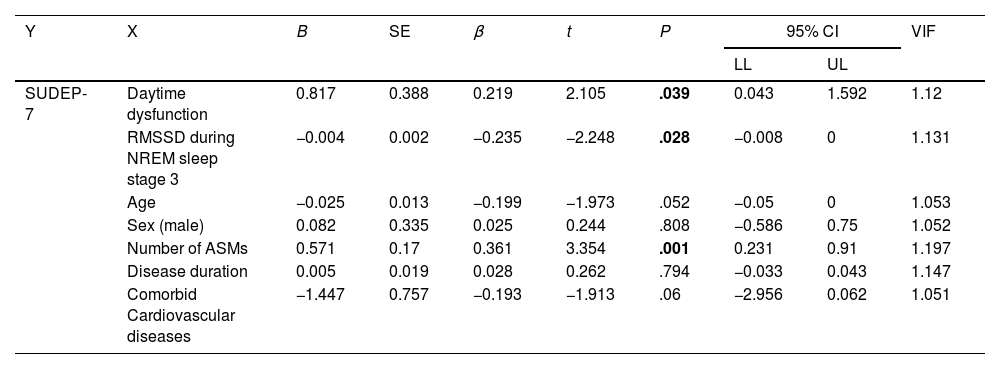

Daytime dysfunction is an independent risk factor for SUDEPMultiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify independent risk factors for SUDEP. The SUDEP-7 score was set as the dependent variable, with presence/absence of daytime dysfunction, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3, age, sex, number of ASMs, disease duration, and presence/absence of comorbid cardiovascular diseases as independent variables, which are reported to be closely associated with SUDEP.17,18 The analysis revealed that daytime dysfunction, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3, and the number of ASMs taken were risk factors for SUDEP (OR: 0.219, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.043–1.592, P=.039; OR: −0.235, 95% CI, −0.008 to 0.000, P=.028; and OR: 0.361; 95% CI, 0.231–0.91, P=.001, respectively) (Table 2).

SUDEP analysed by the stepwise multiple linear regression model.

| Y | X | B | SE | β | t | P | 95% CI | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||||

| SUDEP-7 | Daytime dysfunction | 0.817 | 0.388 | 0.219 | 2.105 | .039 | 0.043 | 1.592 | 1.12 |

| RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 | −0.004 | 0.002 | −0.235 | −2.248 | .028 | −0.008 | 0 | 1.131 | |

| Age | −0.025 | 0.013 | −0.199 | −1.973 | .052 | −0.05 | 0 | 1.053 | |

| Sex (male) | 0.082 | 0.335 | 0.025 | 0.244 | .808 | −0.586 | 0.75 | 1.052 | |

| Number of ASMs | 0.571 | 0.17 | 0.361 | 3.354 | .001 | 0.231 | 0.91 | 1.197 | |

| Disease duration | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.028 | 0.262 | .794 | −0.033 | 0.043 | 1.147 | |

| Comorbid Cardiovascular diseases | −1.447 | 0.757 | −0.193 | −1.913 | .06 | −2.956 | 0.062 | 1.051 | |

β: standardised regression coefficient; ASM: anti-seizure medication; B: unstandardised regression coefficient; SE: standard error; CI: confidence interval; LL: lower limit; NREM: non-rapid eye movement sleep; RMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SUDEP-7: 7-item Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy Risk Assessment; t: process value of t test; UL: upper limit; VIF: variance inflation factor.

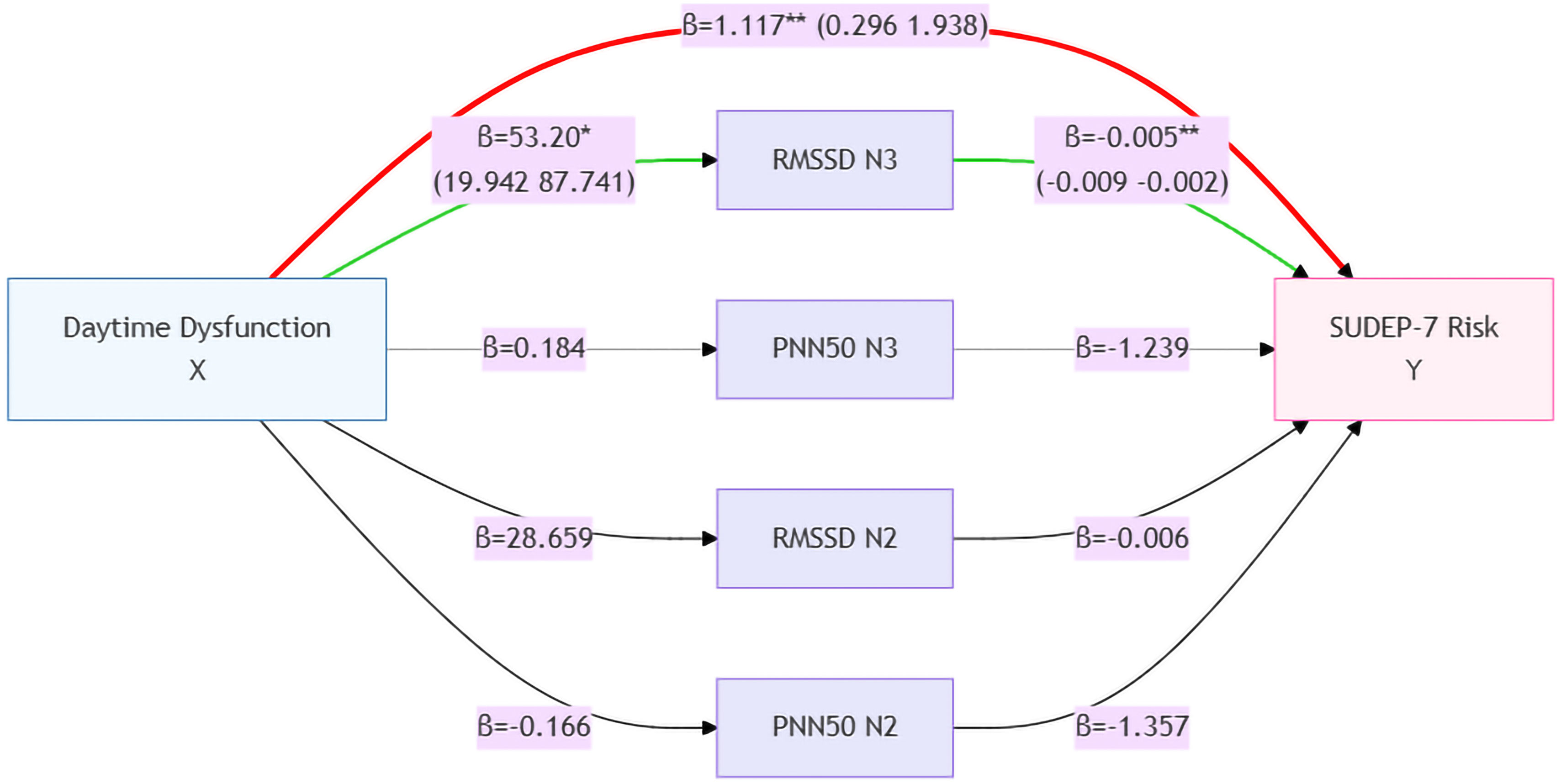

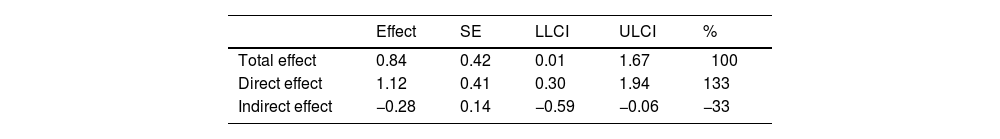

As both daytime dysfunction and SUDEP-7 scores were correlated with HRV time-domain parameters (RMSSD and PNN50) during NREM sleep stages 2 and 3, a mediation model was applied to assess whether these HRV parameters mediated the relationship between daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk. As shown in Fig. 4 and Table 3, while daytime dysfunction had a significant direct effect on SUDEP risk, HRV parameters such as RMSSD and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 2 and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3 did not demonstrate a significant mediating effect. Interestingly, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 exhibited an inverse effect on both daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk (see Fig. 4). Additionally, the direct effect of daytime dysfunction on SUDEP risk was 133%, higher than the total effect when RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 was included as a mediating variable (Table 3).

Results of the mediation analysis. The left part of the figure indicates that daytime dysfunction is the independent variable; the mediating variables of heart rate variability are listed in the middle part; and the right part is the dependent variable, SUDEP-7 score. The values of effect sizes for each mediating model are listed beside every arrowed line, representing positive or negative effects between 2 neighbouring parameters. Daytime dysfunction had a significant direct effect on the risk of SUDEP; however, HRV parameters including RMSSD and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 2 and PNN50 during NREM sleep stage 3 had no obvious mediating effects, and RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 even had an inverse effect on daytime dysfunction and the risk of SUDEP. *P<.05, **P<.01. The red path represents the total effect pathway, the green path represents the mediating effect pathway, and the remaining colours indicate the mediating effect pathways that are not significant. HRV: heart rate variability; NREM: non-rapid eye movement sleep; PNN50: percentage of NN50 intervals; RMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; SUDEP-7: 7-item SUDEP Risk Assessment.

Mediation analysis of RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 on daytime dysfunction and the risk of SUDEP.

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | 0.84 | 0.42 | 0.01 | 1.67 | 100 |

| Direct effect | 1.12 | 0.41 | 0.30 | 1.94 | 133 |

| Indirect effect | −0.28 | 0.14 | −0.59 | −0.06 | −33 |

LL: lower limit of confidence interval; NREM: non-rapid eye movement; RMSSD: root mean square of successive differences; SE: standard error; SUDEP: sudden unexpected death in epilepsy; ULCI: upper limit of confidence interval.

This study identified daytime dysfunction as an independent risk factor for SUDEP. While daytime dysfunction and SUDEP-7 scores were correlated with time-domain HRV parameters (RMSSD and PNN50) during NREM sleep stages 2 and 3, these HRV parameters did not mediate the effect of daytime dysfunction on SUDEP risk. This suggests that other mechanisms, beyond heart rate variability (HRV), may play a role in increasing SUDEP risk in patients with epilepsy.

Another explanation for the inverse relationships between RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 and SUDEP risk is compensatory vagal hyperactivity in response to chronic autonomic instability.19 Patients with severe daytime dysfunction and higher SUDEP risk might exhibit transient parasympathetic surges during deep sleep, masking underlying autonomic dysfunction. Alternatively, this finding could indicate impaired autonomic adaptability, where reduced HRV variability fails to buffer physiological stressors, increasing vulnerability to cardiorespiratory failure during seizures.

Our findings are consistent with the results of previous studies that emphasise the role of autonomic dysfunction in SUDEP. For example, patients with nocturnal seizures exhibit significant alterations in HRV and autonomic network connectivity during sleep, which may elevate SUDEP risk.20 Moreover, frequent nocturnal seizures and sleep disturbances, such as sleep apnoea, have been implicated as risk factors in SUDEP, given their impact on both autonomic regulation and cardiovascular function.21,22 Patients with daytime dysfunction often present with uncontrolled seizures, which may mask underlying sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnoea. Therefore, polysomnography should be considered in patients showing signs of daytime dysfunction, in order to assess sleep quality and potential breathing disorders.

We also confirmed that 33.9% of patients in our cohort had poor sleep quality, as assessed by the PSQI and ESS; this is consistent with previous findings.23 Although there were no correlations between subjective and objective sleep measures, cycle 1 duration (the first sleep cycle) was shorter in patients with higher PSQI scores, suggesting that shorter cycle 1 duration may reflect poor objective sleep quality.

HRV parameters, particularly RMSSD and PNN50, measure short-term variations in heart rate and predominantly reflect vagal tone.24 Our findings showed that poor sleep quality (shorter cycle 1 duration and more arousals) was associated with higher RMSSD and PNN50 values during NREM sleep stages 2 and 3, indicating vagal predominance during sleep. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with epilepsy, particularly those at risk of SUDEP, show reduced parasympathetic activity and altered HRV.9,25 These HRV reductions have been correlated with SUDEP risk, particularly in patients with frontal and temporal lobe epilepsy.26

Despite these significant correlations between HRV parameters, daytime dysfunction, and SUDEP risk, mediation analysis indicated that HRV did not mediate the relationship between daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk. In fact, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 showed an inverse effect, suggesting that alternative mechanisms may be associated with the risk of SUDEP in patients with daytime dysfunction. Potential mechanisms may include cardiorespiratory instability or impaired autonomic responses during sleep, as reported in patients who experience significant fluctuations in heart rate and breathing following seizures.27 Further research is needed to elucidate these mechanisms and explore the complex relationship between sleep, autonomic dysfunction, and SUDEP.28

LimitationsThis study presents several limitations. First, the reliance on subjective sleep questionnaires may introduce potential recall bias, particularly as we operationalised daytime dysfunction using a single-item metric from the PSQI. Furthermore, the SUDEP-7 inventory assesses potential risk rather than actual SUDEP cases, which may limit the accuracy of risk prediction. Second, the “first-night effect” may have affected sleep quality, as patients were monitored in a clinical setting rather than in their home environment. In addition, while long-term scalp EEG provided high temporal resolution for ictal–interictal characterisation, the absence of synchronised polysomnography parameters such as respiratory effort channels and pulse oximetry may preclude the definitive exclusion of hypoxaemia-related confounders during sleep-state transitions. Moreover, we explicitly recognise that the modest sample size and single-centre design impose constraints on the external validation of our findings. A prospective multicentre study with embedded machine learning architectures may be designed in the future.

ConclusionIn conclusion, we observed that daytime dysfunction, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3, and the number of ASMs were independent risk factors for SUDEP in epilepsy patients. While HRV parameters, including RMSSD and PNN50, were significantly correlated with daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk, they did not mediate the relationship between daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk. Additionally, RMSSD during NREM sleep stage 3 showed an inverse effect on daytime dysfunction and SUDEP risk, suggesting that alternative mechanisms may be involved. Future research should investigate these mechanisms, including the potential role of cardiorespiratory dysfunction and autonomic instability in SUDEP.

Author contributionsWP designed the study, reviewed the analysis of article data, and revised the manuscript. ZS collected clinical and EEG data, conducted the statistical work, and drafted the figures. ZH did parts of the statistical work. RT collected parts of cases. XW instructed the study design. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalAll procedures involving the patients complied with the ethical standards of our institutional and national research committees and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

FundingThis study was funded by Science and Technology Plan Project of Fujian Province (2021GGB033).

Conflict of interestThe authors claim no competing interests.

Data availability statementData with no identifiable patients and hospitals will be available to any researcher who provides a methodological study proposal approved by our study team.

We are grateful to Prof. Masud Seyal at University of California Davis, who reviewed the manuscript and gave many beneficial suggestions. We thank Jiatong Li, who developed the ECOMB software to analyse heart rate variability parameters in this study. Finally, we thank the patients for participating in this study.