Myasthenia gravis is the most common autoimmune disorder of neuromuscular junction that classically presents with fatigable weakness of ocular, bulbar, respiratory, and limb muscles with some diurnal variation.1,2 In up to 85% of cases, autoantibodies binding to acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) in the postsynaptic membrane of the neuromuscular junction can be found.1,2 Besides, there are other autoantibodies described, such as those against the muscle-specific kinase (MuSK) or to AChR-related proteins in the postsynaptic muscle membrane (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 [LRP4] and cortactin); of note is a relatively rare entity called seronegative myasthenia gravis.2–5

Localized or generalized muscle weakness is the predominant symptom triggered by AChR antibodies.2 Myasthenia gravis is classified clinically as ocular and generalized. Facial weakness is frequent in generalized myasthenia gravis, but it is very uncommon if it is not accompanied by involvement of ocular musculature.6–8

We report a case of generalized myasthenia gravis who presented with bilateral facial palsy as the sole initial manifestation without extraocular muscle involvement, which would reinforce the existence of this scarce phenotypic variant.

Case presentationA 28-year-old female from rural West Bengal, India, was brought to our clinic with a complaint of recent onset persistent facial asymmetry, inability to close her eyes tightly, inability to blow and whistle, and slurring of speech for the last ten days. Two days after admission, she also complained of difficulty in deglutition and progressively worsening voice, i.e., nasal intonation and dysphonia. She was the mother of two healthy children with no comorbidities. She denied any problems in extraocular movements, blurry/double vision (even during periods of extended visual concentration), drooping of eyelids during prolonged television watching, and difficulty in chewing/jaw muscle fatigue, tongue movement, and limb weakness during climbing stairs or washing/shampooing her hair/face. The general examination was unremarkable except for an expressionless face with almost symmetrical lower lip drooping. A neurological examination revealed normal cognitive abilities, nearly symmetrical bilateral lower motor neuron-type facial palsy, lagophthalmos, and Bell's phenomenon. She had profound difficulty blowing her cheeks and pursing her lips, and her speech had an increasingly nasal tone (i.e., fatigable dysarthria and dysphonia). There was no manifest diplopia, ptosis, ophthalmoparesis, neck flexion/extension weakness, shoulder abduction weakness, hip flexion weakness, and proximal muscle weakness observed on several serial examinations. Even after sustained upgaze, the ice pack test failed to show any ptosis improvement. The curtain sign was negative. According to the Medical Research Council grading, muscle strength was 5/5 in all proximal and distal limb muscles.

Complete blood cell count, liver, kidney, thyroid function tests, and electrolytes were within normal limits. Serological tests for syphilis, Lyme disease, Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella-zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus 1/2, and hepatitis B and C viruses were negative. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium and cerebrospinal analysis were unremarkable. In the meantime, since day three of admission, she gradually developed progressive difficulty in neck holding and mild shortness of breath on exertion and prolonged talking. An urgent bedside nerve conduction study ruled out Guillain–Barré syndrome. Repetitive nerve stimulation and electromyography studies revealed a significant amplitude decrease in both right and left facial nerves after 1, 2, 3, and 4min of exertion. He also tested positive for AChR antibodies. Anti-musk antibodies, anti-ganglioside antibodies, anti-nuclear antibodies profile, p-ANCA, c-ANCA, antiphospholipid antibody panel, and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme level were non-contributory. Considering the impending myasthenic crisis, she was shifted to the intensive care unit, put on intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIG), and planned for plasma exchange if required. However, she responded readily to IVIG and pyridostigmine, and neck holding improved alongside dysarthria, dysphagia, and dysphonia. Bilateral facial palsy got improved, too. She underwent a thoracoabdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan, excluding any underlying thymoma or other neoplasm and features of pulmonary sarcoidosis. A definitive diagnosis of generalized myasthenia gravis was made based on clinical, serological, and electrophysiological tests. She was discharged on pyridostigmine (60mg four times a day), prednisolone (40mg/day with a plan for slow tapering), and mycophenolate mofetil (1000mg/day). She was advised to use strict barrier contraceptive measures, and to avoid certain medications that may worsen/precipitate weakness and was followed up monthly. After six months of follow-up, she is living near normal daily life activities unassisted.

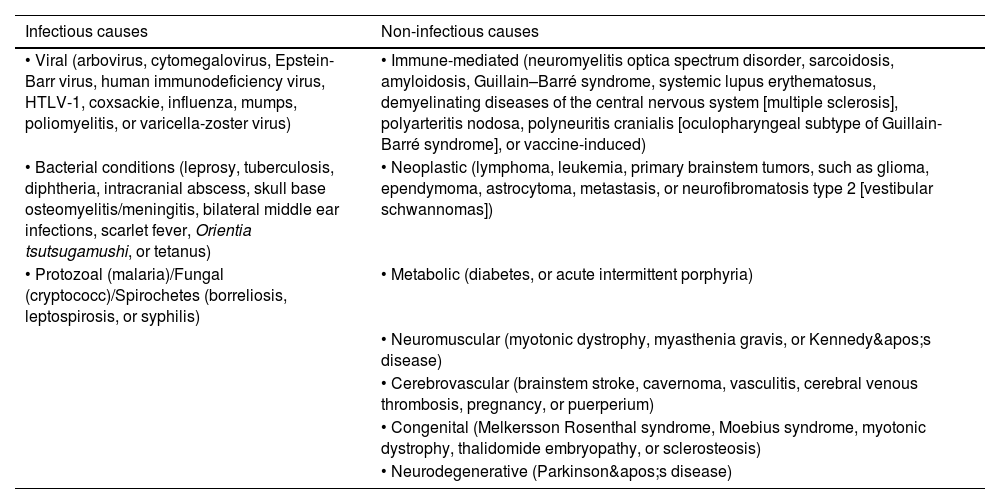

DiscussionUnlike unilateral facial palsy, bilateral facial nerve palsy is rare and creates many diagnostic dilemmas. The etiologies of non-iatrogenic, non-traumatic bilateral facial nerve palsy can be classified as follows in Table 1.9–14 Immaculate history taking, meticulous physical examinations, and detailed investigations are indispensable for the evaluation of the etiological basis of a case of bilateral facial nerve palsy. Historical pointers like onset, synchronicity, sequence, recurrence and course of symptomatology, presence/absence of associated symptoms like double/blurry vision, abnormal facial sensation, taste perception, ear-related symptoms, and new-onset neurological deficits like motor limb paresis, sensory dysesthesia, oculomotor paresis, bulbar weakness, cerebellopathy, or features of raised intracranial pressure, recognizing the pattern of neurological deficits (i.e., central vs. peripheral weakness, symmetrical vs. asymmetrical weakness, upper vs. lower motor neuron type of weakness, and fatigability/variable weakness) and relevant risk factors assessment are sine-qua-non.

Causes of non-iatrogenic, non-traumatic bilateral facial nerve palsy (original table).

| Infectious causes | Non-infectious causes |

|---|---|

| • Viral (arbovirus, cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human immunodeficiency virus, HTLV-1, coxsackie, influenza, mumps, poliomyelitis, or varicella-zoster virus) | • Immune-mediated (neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, Guillain–Barré syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system [multiple sclerosis], polyarteritis nodosa, polyneuritis cranialis [oculopharyngeal subtype of Guillain-Barré syndrome], or vaccine-induced) |

| • Bacterial conditions (leprosy, tuberculosis, diphtheria, intracranial abscess, skull base osteomyelitis/meningitis, bilateral middle ear infections, scarlet fever, Orientia tsutsugamushi, or tetanus) | • Neoplastic (lymphoma, leukemia, primary brainstem tumors, such as glioma, ependymoma, astrocytoma, metastasis, or neurofibromatosis type 2 [vestibular schwannomas]) |

| • Protozoal (malaria)/Fungal (cryptococc)/Spirochetes (borreliosis, leptospirosis, or syphilis) | • Metabolic (diabetes, or acute intermittent porphyria) |

| • Neuromuscular (myotonic dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, or Kennedy's disease) | |

| • Cerebrovascular (brainstem stroke, cavernoma, vasculitis, cerebral venous thrombosis, pregnancy, or puerperium) | |

| • Congenital (Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome, Moebius syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, thalidomide embryopathy, or sclerosteosis) | |

| • Neurodegenerative (Parkinson's disease) |

Myasthenia gravis often affects muscles innervated by the cranial nerves, reducing facial expression and speech and swallowing weakness. Oculo-bulbar muscle weakness is the most frequent, but patients can develop more generalized myasthenia gravis involving proximal muscles of the extremities and the trunk (including the neck).2

As far as we know, this would be the fourth reported case of generalized myasthenia gravis with bilateral facial palsy as a presenting clinical feature without extraocular muscle involvement.6–8 However, ours is the first case preceding myasthenic crisis, not due to therapy discontinuation, which would reinforce the possibility of representing a surrogate marker of myasthenic crisis. In a similar myasthenia gravis case,8 a myasthenic crisis (dysphonia and dysphagia, but without respiratory failure) appeared because of corticosteroid tapering.

Our case highlights the importance of including myasthenia gravis in the differential diagnosis of entities causing bilateral facial palsy, even when the involvement of the extraocular muscles does not simultaneously accompany it. It is paramount to ask for repetitive nerve stimulation, AChR antibodies, and other antibodies (MuSK, LRP4, and cortactin) in case of a strong clinical suspicion of myasthenia gravis for diagnostic confirmation. Early recognition of this clinical scenario could help achieve prompt diagnosis and proper treatment before a myasthenic crisis appears.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled criterion as established by the ICMJE.

Informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient participating in the study (consent for research).

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no relevant disclosures.

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (grant RTC-2015-3967-1, NetMD – platform for the tracking of movement disorder), and the Spanish Health Research Agency (grant FIS PI12/01602 and grant FIS PI16/00451).