Wernicke's encephalopathy (WE) is a life-threatening illness caused by vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency, which is reversible if intravenous vitamin B1 therapy is started early.1 The prevalence of WE ranges from 0.4 to 2.8%.2–8 If not appropriately managed, it can cause severe neurologic disorders such as seizures, Korsakoff psychosis, and even death.1–8

Alcoholism justifies 50% of WE cases.5 Thus, nonalcoholic WE patients are also frequently seen and are likely to present with different symptoms and imaging findings, which further complicates WE diagnosis.8–10 Mortality rate is about 20%, so prompt recognition and treatment are essential, especially in atypical cases.8 Rarely, thyrotoxicosis (i.e., Graves’ disease) can produce thiamine depletion and WE.11,12

Ocular abnormalities occur in 29% of patients, including nystagmus, symmetrical or asymmetrical palsy of both lateral recti or other ocular muscles, and conjugate-gaze palsies, which result from lesions of the pontine tegmentum and of the abducens and oculomotor nuclei.8 Complete ophthalmoplegia rarely occurs, and horizontal nystagmus is the most frequent ocular impairment at presentation.13

Thiamine deficiency can cause beriberi, either “dry” (without fluid retention) or “wet” (associated with cardiac failure with edema).14 Beriberi usually occurs in low-income groups with poor diets.14 Dry beriberi is characterized by polyneuropathy, which has a severity that correlates with the degree and duration of thiamine deficiency.14

We report the case of an Indian alcoholic patient with WE and dry beriberi, likely precipitated by undiagnosed Graves’ disease. The patient exhibited isolated involvement of the cerebellum and corpus callosum, along with combined bilateral cranial nerve paresis (III, IV, VI, and VII).

A 35-year-old male from rural West Bengal, India, was brought to the emergency department with acute-onset generalized tonic–clonic seizures, followed by impaired consciousness and cognitive dysfunction. The patient had a history of chronic alcoholism. Four days prior, he experienced a binge drinking episode without any food intake. The following day, he developed multiple episodes of vomiting and a mild fever, which progressively led to horizontal diplopia, unsteady gait, and confusion.

On the day of admission, the patient suffered from seizure clusters, requiring airway management. He was immediately treated with a single bolus of intravenous lorazepam, thiamine (200mg), and a dextrose infusion (capillary blood glucose: 80mg/dL). His vital signs stabilized shortly after that.

Laboratory analyses revealed moderate elevations in liver enzymes (ALT 351U/L, AST 798U/L, GGT 112U/L). Thyroid function tests showed primary hyperthyroidism with TSH-receptor antibody positivity, consistent with Graves’ disease. Blood glucose, vitamin B12, folate, calcium, ammonia, amylase, and lipase levels were all within normal limits. A bedside electroencephalogram revealed generalized background slowing.

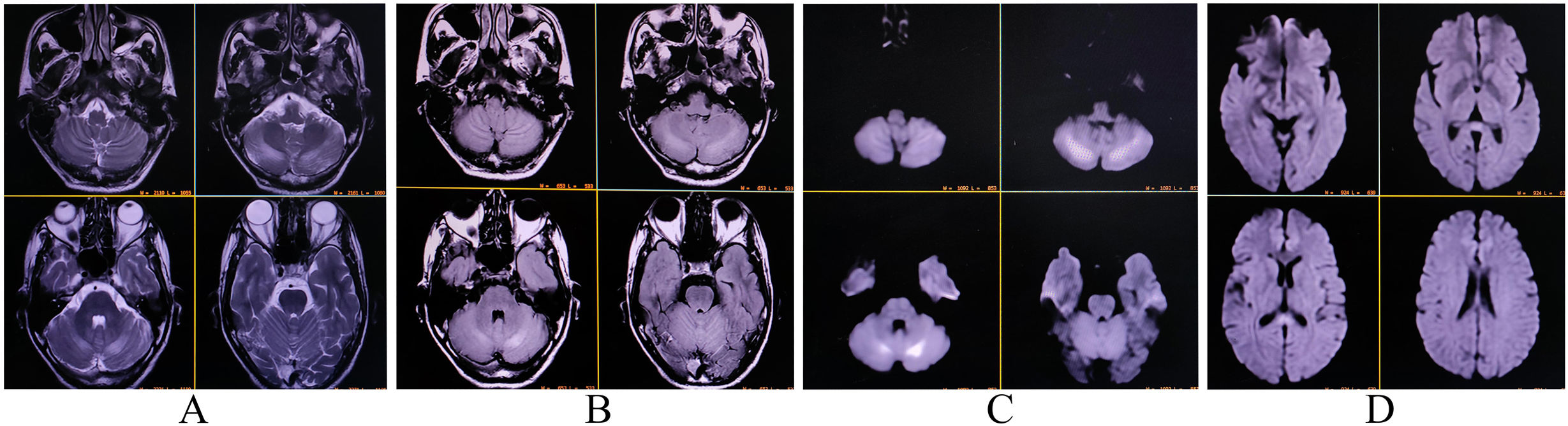

Nerve conduction studies indicated symmetrical sensory-motor axonal polyneuropathy in the lower limbs, characterized by reduced amplitudes of sensory nerve action potentials and compound muscle action potentials, along with normal or mildly reduced conduction velocities and neuropathic changes. T2-FLAIR magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed hyperintensities in both cerebellar hemispheres and the splenium of the corpus callosum, with diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging (Fig. 1). The fundoscopic examination was normal. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis ruled out infectious and inflammatory causes. Tests for relevant neuroviruses, autoimmune markers, and paraneoplastic antibodies were negative.

Given the high suspicion of alcoholic WE with atypical neuroimaging features, the patient's thiamine dose was increased to 1500mg/day. After one week, he showed complete recovery from confusion and cognitive disturbances. A detailed neurological examination revealed bilateral lateral gaze paresis with horizontal and vertical nystagmus, along with signs of pan-cerebellar dysfunction: severe titubation, appendicular and truncal ataxia, gait instability, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesis, and scanning speech. Cranial nerve examination demonstrated bilateral asymmetrical paresis of cranial nerves III, IV, VI, and VII (right more affected than left). Sensory examination revealed mildly reduced sensation in the lower limbs, consistent with distal sensory polyneuropathy. The patient displayed no signs of Korsakoff psychosis or amnesia.

After one week, serum thiamine levels were confirmed to be deficient, supporting the diagnosis of WE and dry beriberi, likely triggered by Graves’ disease. The thiamine dose was subsequently reduced to 500mg/day for the next five days, and the patient was discharged with oral benfotiamine (300mg/day), carbimazole (30mg/day), and propranolol (60mg/day). He was advised to seek treatment at a de-addiction clinic for chronic alcoholism.

At the four-week follow-up, the patient exhibited mild ataxic speech, abnormal tandem gait, and bilateral lateral gaze restrictions but otherwise showed significant improvement.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a confirmed alcoholic WE patient presenting with dry beriberi and isolated involvement of the cerebellum and corpus callosum, accompanied by combined bilateral cranial nerve paresis (III, IV, VI, and VII),15 precipitated by Graves’ disease.11,12 This unique presentation may represent a novel clinical-radiological variant.

Brain MRI in WE typically reveals bilateral hyperintensities on T2-FLAIR sequences in the paraventricular regions of the thalamus, hypothalamus, mammillary bodies, periaqueductal region, and the floor of the fourth ventricle.1,7 Notably, MRI findings in alcoholic WE patients differ from those in nonalcoholic patients.9 Alcohol abuse may alter the blood-brain barrier, leading to more frequent contrast enhancement in the mammillary bodies and thalami compared with nonalcoholic patients, suggesting that these regions may be particularly vulnerable to alcohol's toxic effects. In contrast, atypical radiological findings of brain lesions—such as in the putamen, caudate, splenium of the corpus callosum, dorsal medulla, pons, red nucleus, substantia nigra, cranial nerve nuclei, vermis, dentate nucleus, paravermian region of the cerebellum, fornix, and pre- and postcentral gyri—are more characteristic of nonalcoholic WE patients.1,9 However, typical findings can also be present in nonalcoholic patients.16

The pathophysiology of WE involves mitochondrial dysfunction due to thiamine deficiency, impairing both the Krebs cycle and the pentose phosphate pathway.1 This disruption in energy metabolism leads to the development of cytotoxic and vasogenic edema, as observed in this patient's atypical neuroimaging. Interestingly, although bilateral cranial nerve involvement was observed clinically in our patient, the cranial nerve nuclei appeared unaffected on neuroimaging. This dissociation suggests that specific brain regions may be spared from damage due to the maintenance of cellular osmotic gradients, which could help preserve physiological thiamine levels in the cranial nerve nuclei. Zuccoli et al.15 reported similar findings in a nonalcoholic Wernicke's encephalopathy patient, where cranial nerve nuclei lesions were observed but did not become clinically evident, potentially due to the same protective mechanisms.

In summary, our case emphasizes the importance of (1) understanding the pathophysiology, predisposing factors, symptoms, and neuroimaging features of WE; (2) evaluating thyroid hormone levels and TSH-receptor antibodies in patients with atypical neuroimaging findings, especially in alcoholic WE; and (3) assessing serum thiamine levels when WE or dry beriberi is suspected, to confirm the diagnosis and promptly initiate thiamine repletion therapy.

The unique presentation of WE in this patient highlights the need for heightened clinical suspicion in atypical cases. The rare co-occurrence of dry beriberi and Graves’ disease, along with multiple cranial neuropathies and isolated cerebellar and corpus callosum involvement, adds further complexity to the diagnostic process.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled criterion as established by the ICMJE.

Authors noteWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient participating in the study (consent for research).

Study fundingNil.

Conflict of interestDr. Abhirup Nag (nagabhirup.96@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Moisés León-Ruiz (pistolpete271285@hotmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Kunal Bole (bolekunal@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Ritwik Ghosh (ritwikmed2014@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Dinabandhu Naga (drdbandhu@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Julián Benito-León (jbenitol67@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

J. Benito-León is supported by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA (NINDS #R01 NS39422), the European Commission (grant ICT-2011-287739, NeuroTREMOR), and The Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan at the Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant TED2021-130174B-C33, NETremor).