Blind EEG analysis, especially in the case of suspected nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE), can lead to misdiagnosis. It is important to consider patient demographic and clinical information when interpreting EEG recordings, which constitutes a limitation of automatic seizure detectors. This study aims to quantify the impact of this information on EEG interpretation in cases of suspected NCSE.

MethodsEEG recordings from patients with suspected NCSE were analysed by 2 independent reviewers, first without and subsequently with access to clinical data. Inter-rater agreement between the reviewers and with the reference standard was analysed by calculating Cohen's kappa. Diagnoses issued in the blind and informed conditions were compared using performance metrics, and statistically using McNemar's test.

ResultsOur study included 132 EEG recordings from 75 patients. Of these, 56 recordings were classified as NCSE by the physician at the time of assessment. Access to patient clinical data prompted a change in the diagnoses issued by reviewers 1 and 2 in 12% and 17% of recordings, respectively, and resulted in a marked increase in both inter-rater agreement and performance metrics, although these changes were not statistically significant.

ConclusionsEEG patterns can be interpreted differently depending on the clinical context. Access to patient demographic and clinical information improves EEG interpretation.

El análisis de registros de electroencefalografía (EEG) sin acceso a información clínica, particularmente en casos de sospecha de estatus epiléptico no convulsivo, puede culminar en un diagnóstico erróneo. A la hora de interpretar los registros de EEG es importante tener en cuenta los datos demográficos y clínicos de los pacientes, lo que supone una limitación para los detectores de ataques epilépticos. El objetivo de nuestro estudio es cuantificar el impacto de esta información en la interpretación de registros de EEG en casos de sospecha de estatus epiléptico no convulsivo.

MétodosDos revisores independientes revisaron los registros de EEG de pacientes con posible estatus epiléptico no convulsivo, primero sin acceso a los datos clínicos y después accediendo a ellos. La concordancia entre los revisores y con el estándar de referencia se analizó calculando el coeficiente kappa de Cohen. Los diagnósticos establecidos con y sin acceso a los datos clínicos se compararon mediante indicadores de desempeño, y el análisis estadístico se realizó con la prueba de McNemar.

ResultadosNuestro estudio incluyó 132 registros de EEG de 75 pacientes, de los cuales 56 registros fueron considerados estatus epiléptico no convulsivo por el facultativo en el momento de la valoración. El acceso a los datos clínicos de los pacientes conllevó un cambio en el diagnóstico establecido por el revisor 1 y el revisor 2 en el 12% y el 17% de los registros, respectivamente. Esto provocó un marcado aumento en tanto la concordancia interevaluador como en los indicadores de desempeño, aunque estas variaciones no fueron significativas desde el punto de vista estadístico.

ConclusionesLos patrones de EEG pueden ser interpretados de diversas formas dependiendo del contexto clínico. El acceso a los datos demográficos y clínicos de los pacientes mejora la interpretación de los registros de EEG.

Status epilepticus, a life-threatening condition arising either from failure of the mechanisms responsible for seizure termination or from the activation of mechanisms that cause abnormally prolonged seizures,1 may be classified broadly as convulsive or nonconvulsive status epilepticus (NCSE). Diagnosis of NCSE is highly challenging, and is based on a combination of clinical history data, seizure semiology, and EEG findings. Unfortunately, the clinical manifestations of NCSE are usually subtle and nonspecific,2–4 with the most frequent being impaired level of consciousness, ranging from mild confusion to coma.5–7 In these cases, EEG is crucial for diagnosis.1,8 The latest EEG-based diagnostic criteria for NCSE are the modified Salzburg criteria, which incorporate the standardised nomenclature of the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society to increase homogeneity and improve inter-rater agreement.9,10 These criteria consider the EEG pattern, clinical manifestations, and response to antiseizure medication to establish a diagnosis of definite NCSE, possible NCSE, or no NCSE. The decision to start treatment in the event of possible NCSE rests in the hands of the treating physician, and should be made on an individual basis. As noted above, both patient medical history and seizure semiology are crucial in treatment decision-making, as some EEG patterns may be of uncertain significance (for example, benign variants or periodic discharges),11,12 and there is no consensus on which EEG patterns warrant aggressive treatment in comatose patients.12 Thus, 2 very similar EEG recordings may lead to different therapeutic decisions, depending on the context.

On the other hand, the use of automatic seizure detection techniques has expanded.13,14 The development of these systems aims to provide an initial diagnosis at centres where EEG is not readily available, as well as an automated analysis of prolonged EEG recordings, which must otherwise be manually reviewed. While automatic seizure detectors can be very useful in certain scenarios, they rely exclusively on EEG signals. Treatment must not be based solely only on the diagnosis established by the detection device, but must also consider the patient's medical history and clinical status.

Although the importance of the medical history and physical examination is universally acknowledged in medicine, this study aims to quantify their relevance in EEG interpretation when NCSE is suspected. Our findings may contribute to the design and improvement of new automatic seizure detection systems.

Material and methodsPatient selectionWe conducted an observational, analytical, single-centre study of the impact of clinical data on EEG interpretation. A retrospective search was conducted on the EEG database of Clínica Universidad de Navarra for EEG recordings compatible with NCSE taken between 2004 and 2022. The only exclusion criterion was patient age under 18 years. Another search was made to identify normal EEG recordings, EEG recordings compatible with encephalopathy (characterised by generalised or focal background slowing and/or triphasic waves), and abnormal EEG recordings that were not categorised as being compatible with NCSE or encephalopathy. The latter category includes recordings with interictal epileptiform abnormalities and/or focal slow waves. The inclusion of EEG recordings revealing encephalopathy is of paramount importance given that this condition is frequently considered in the differential diagnosis of NCSE8,15,16 due to the initial unexplained altered level of consciousness observed in these patients. In patients already included in the database due to EEG findings compatible with NCSE and with previous or subsequent normal EEG findings, pathological EEG recordings were preferentially included, while the remaining recordings were added in chronological order. Although this approach resulted in an asymmetrical contribution of EEG recordings, with some patients having multiple EEG records while others had only one, the reviewers were not informed of this fact.

EEG recordingsEEG recordings were obtained at Clínica Universidad de Navarra with a 19-channel EEG cap, or a double-distance montage (Fp1, Fp2, C3, C4, T3, T4, O1, O2, Cz) with adhesive surface electrodes, when placement of a cap was not possible. Electrodes were placed according to the 10–20 system,17 with an impedance below 20kΩ, using a sampling rate of 200–250Hz. EEG studies prior to August 2018 were performed with the Stellate Harmonie software (Canada), while those performed thereafter used the Natus software (USA). EEG recordings had a median duration of 18min (range: 6min to 3h and 54min). Unfortunately, video recordings were not available for review.

Initial blind classificationEEG recordings were independently reviewed by 2 neurophysiologists with training in EEG. During the initial classification, the reviewers were blinded to patient demographic characteristics, medical history, and clinical status at the time of the EEG study. However, they were informed that all EEG studies had been conducted due to suspicion of NCSE, and were instructed to assume that patients presented a low level of consciousness during the study. The reviewers were asked to categorise EEG recordings as either definite NCSE or no NCSE, according to the modified Salzburg criteria.9 While these criteria allow for a diagnosis of “possible NCSE”, this category was not included in our analysis for 2 main reasons. First, the lack of access to clinical information, such as potential manifestations or antiepileptic drug use, precluded the strict application of the modified Salzburg criteria. Second, in real-world clinical practice, a diagnosis of possible NCSE often requires a definitive decision regarding treatment initiation. To enhance the practical applicability of our study, we focused on a binary classification “definite NCSE” vs “no NCSE.”

EEG interpretation with patient informationReviewers were subsequently provided with all the relevant clinical and demographic information. Demographic and clinical data included age at the time of the study, sex, relevant clinical history, history of epilepsy, and medication at the time of the study, as well as a detailed description of the motivation for the EEG study and a thorough description of the patient's clinical status during EEG (level of consciousness, motor or non-motor events, medication administration, and time of administration). Therefore, although no video footage was available, reviewers were informed of any ictal manifestation that may have occurred. Reviewers were instructed to re-review the EEG recordings and reclassify them based on this additional information. They did not have access to the diagnosis issued at the time of the initial assessment at any time during the study. While clinical and demographic information allowed the reviewers to fully apply the modified Salzburg criteria, the need to make a definitive treatment decision in real-world clinical practice remained the focus of our study. Therefore, reviewers were again instructed to provide a conclusive diagnosis (either “definite NCSE” or “no NCSE,”) even with the expanded dataset. This approach aligns with the practical reality of clinical decision-making, where a diagnosis of “possible NCSE” is insufficient to guide immediate treatment decisions. This requirement was intended to ensure that the study reflected the challenges and demands of clinical practice.

Statistical analysisThe Pearson chi-square test was used to evaluate the association between level of consciousness during EEG and diagnosis, and between history of epilepsy and diagnosis. Performance metrics were used to assess the reviewers’ classifications. We assessed inter-rater agreement between the 2 neurophysiologists, as well as between each reviewer and a reference standard, in both the “blind” and “informed” conditions. In this case, the reference standard was the diagnosis made by the physician at the time of the patients’ examination, which was considered the gold standard. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using the Cohen's kappa statistic. To assess the impact of additional information on EEG classification, a comparative analysis was conducted using McNemar's test. For the statistical analysis, a P value<.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with Python (v3.10.9) using the SciPy module (v1.6.1).18

Standard protocol approval, registration, and patient consentThe study was approved by the research ethics board at Clínica Universidad de Navarra (reference number CEI:2023.037). Patients gave written informed consent to the use of their data.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the senior authors, conditional upon compliance with the policies of the research ethics board.

ResultsPatient cohortA total of 132 EEG recordings from 75 patients were included in this study. Of these, 56 recordings from 27 patients were classified as NCSE at the time of the initial examination, while 76 recordings from 63 patients were not compatible with NCSE. The latter group included 23 normal EEG recordings, 32 recordings compatible with encephalopathy, and 21 abnormal recordings not compatible with either diagnosis (14 presented focal slow waves and 7 had interictal epileptiform discharges). The NCSE group included 16 women (59%), with a median age at the time of the study of 67 years (range, 22–85), whereas the no-NCSE group included 36 women (57%), with a median age of 63 years (range, 20–93).

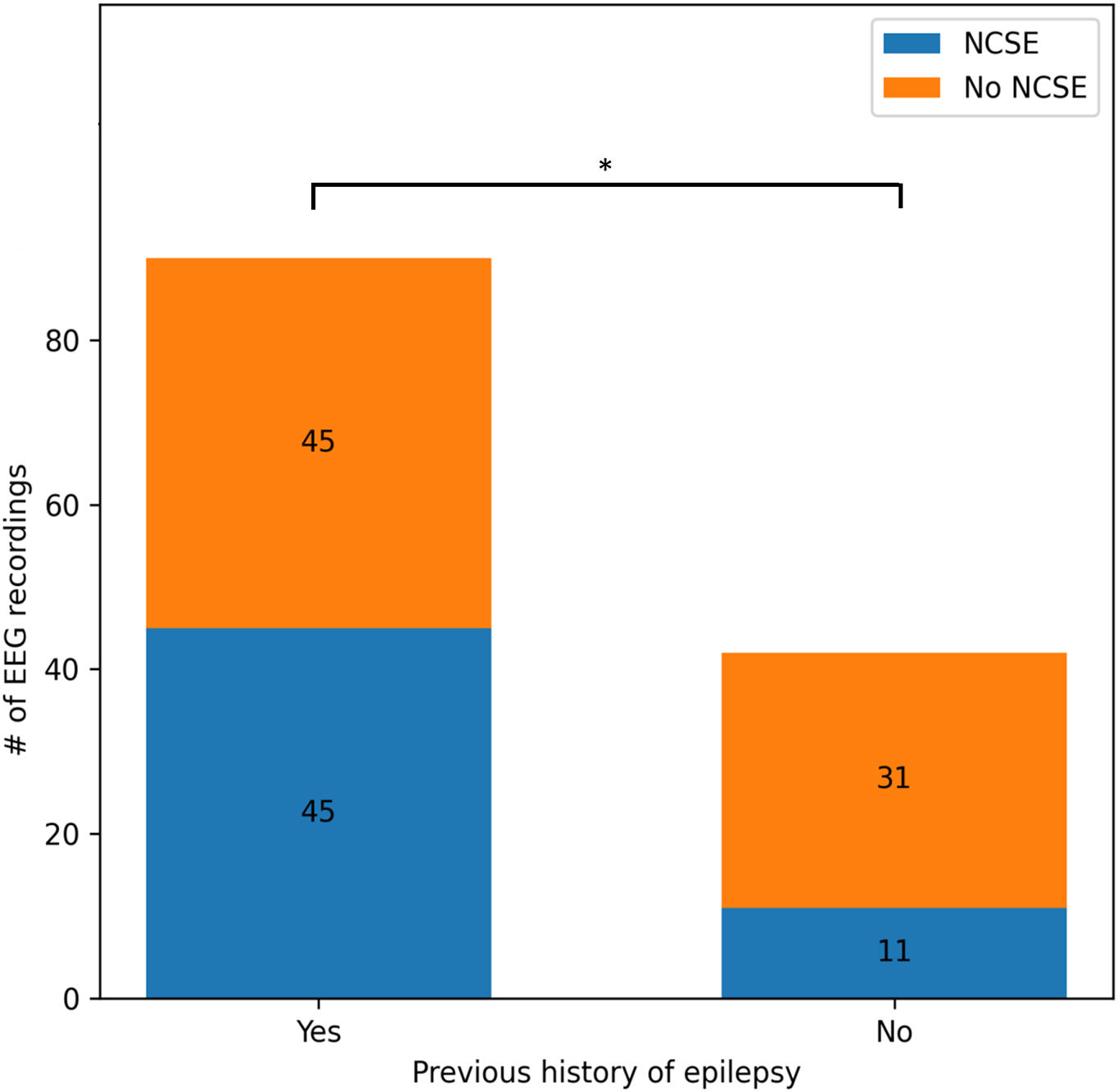

Of the 56 EEG recordings classified as NCSE, 45 corresponded to patients with history of epilepsy (80%). Of the remaining 11 patients, whose first ictal event was status epilepticus, a clear cause was only identified in 3 (central nervous system tumours). Over half of the patients in the no-NCSE group (52%) had a history of epilepsy. We found a statistically significant association between history of epilepsy and diagnosis of NCSE (χ2=5.71; P=.02) (Fig. 1).

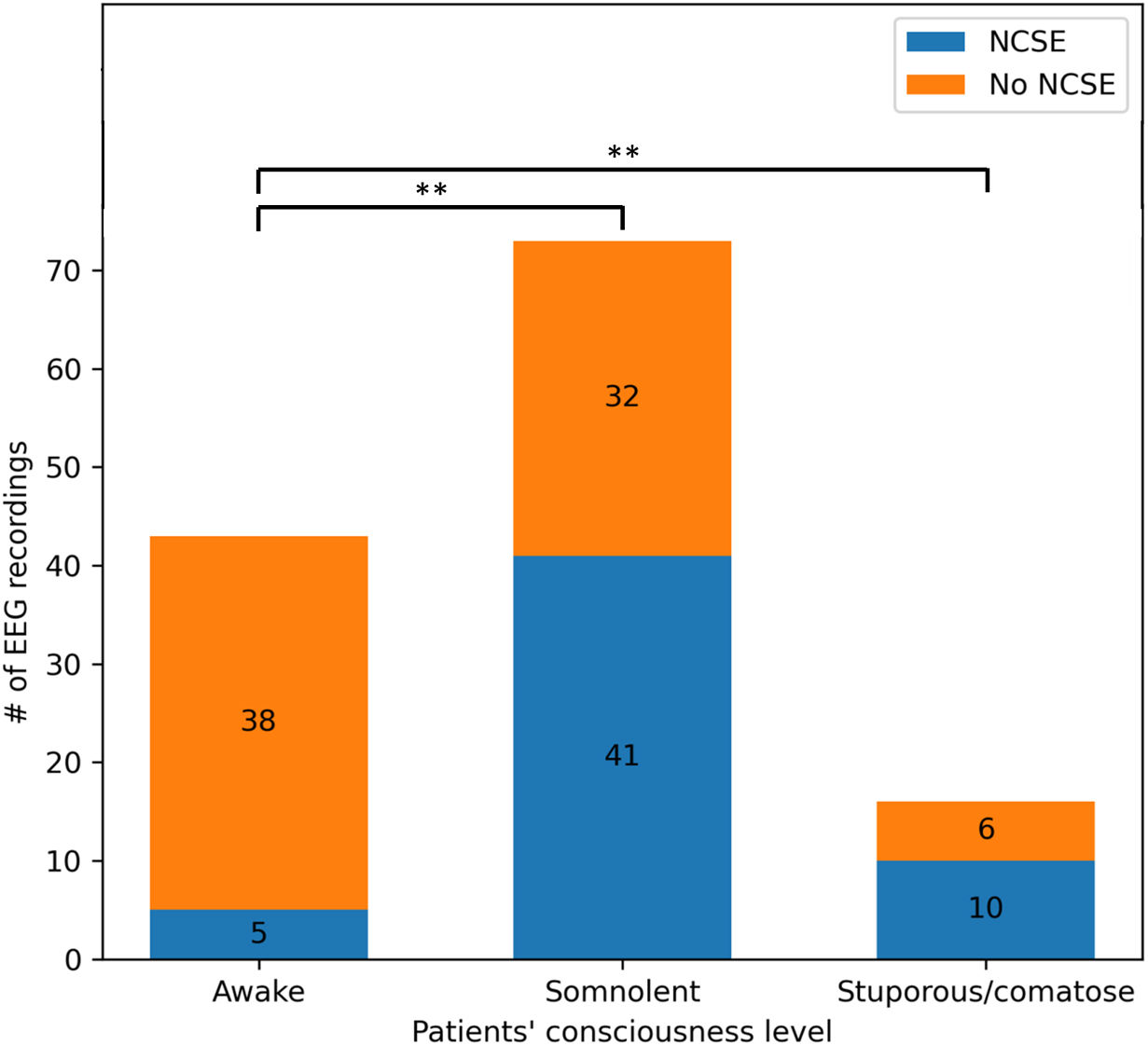

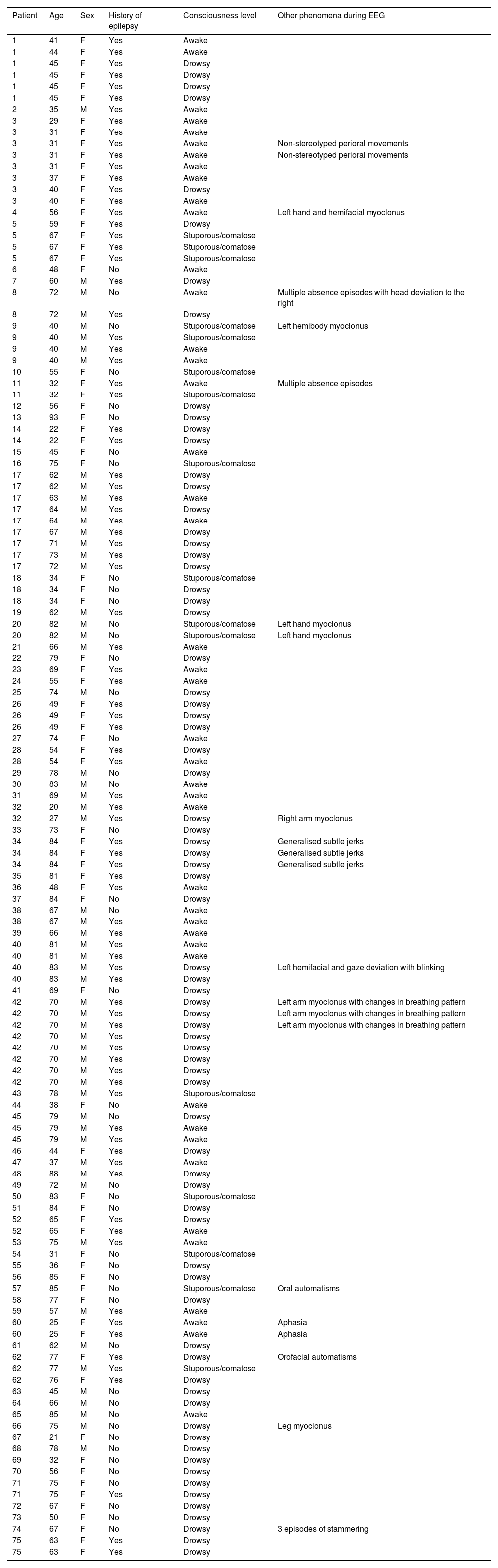

In the NCSE group, 5 recordings (9%) were taken with the patients remaining awake and alert; 41 (73%) had an altered level of consciousness during EEG, and 10 (18%) were stuporous or comatose. In contrast, the no-NCSE group included recordings from 38 awake patients (50%), 32 (42%) with an altered level of consciousness, and 6 (8%) stuporous/comatose patients. Pearson's Chi-square test yielded statistically significant results (χ2=24.98; P<.01), suggesting differences in level of consciousness between the 2 groups (Fig. 2). Demographic and clinical data are summarised in Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical information provided to the reviewers.

| Patient | Age | Sex | History of epilepsy | Consciousness level | Other phenomena during EEG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 41 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 1 | 44 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 1 | 45 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 1 | 45 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 1 | 45 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 1 | 45 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 2 | 35 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 3 | 29 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 3 | 31 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 3 | 31 | F | Yes | Awake | Non-stereotyped perioral movements |

| 3 | 31 | F | Yes | Awake | Non-stereotyped perioral movements |

| 3 | 31 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 3 | 37 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 3 | 40 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 3 | 40 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 4 | 56 | F | Yes | Awake | Left hand and hemifacial myoclonus |

| 5 | 59 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 5 | 67 | F | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 5 | 67 | F | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 5 | 67 | F | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 6 | 48 | F | No | Awake | |

| 7 | 60 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 8 | 72 | M | No | Awake | Multiple absence episodes with head deviation to the right |

| 8 | 72 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 9 | 40 | M | No | Stuporous/comatose | Left hemibody myoclonus |

| 9 | 40 | M | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 9 | 40 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 9 | 40 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 10 | 55 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 11 | 32 | F | Yes | Awake | Multiple absence episodes |

| 11 | 32 | F | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 12 | 56 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 13 | 93 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 14 | 22 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 14 | 22 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 15 | 45 | F | No | Awake | |

| 16 | 75 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 17 | 62 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 62 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 63 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 17 | 64 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 64 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 17 | 67 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 71 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 73 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 17 | 72 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 18 | 34 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 18 | 34 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 18 | 34 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 19 | 62 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 20 | 82 | M | No | Stuporous/comatose | Left hand myoclonus |

| 20 | 82 | M | No | Stuporous/comatose | Left hand myoclonus |

| 21 | 66 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 22 | 79 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 23 | 69 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 24 | 55 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 25 | 74 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 26 | 49 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 26 | 49 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 26 | 49 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 27 | 74 | F | No | Awake | |

| 28 | 54 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 28 | 54 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 29 | 78 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 30 | 83 | M | No | Awake | |

| 31 | 69 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 32 | 20 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 32 | 27 | M | Yes | Drowsy | Right arm myoclonus |

| 33 | 73 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 34 | 84 | F | Yes | Drowsy | Generalised subtle jerks |

| 34 | 84 | F | Yes | Drowsy | Generalised subtle jerks |

| 34 | 84 | F | Yes | Drowsy | Generalised subtle jerks |

| 35 | 81 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 36 | 48 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 37 | 84 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 38 | 67 | M | No | Awake | |

| 38 | 67 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 39 | 66 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 40 | 81 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 40 | 81 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 40 | 83 | M | Yes | Drowsy | Left hemifacial and gaze deviation with blinking |

| 40 | 83 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 41 | 69 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | Left arm myoclonus with changes in breathing pattern |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | Left arm myoclonus with changes in breathing pattern |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | Left arm myoclonus with changes in breathing pattern |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 42 | 70 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 43 | 78 | M | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 44 | 38 | F | No | Awake | |

| 45 | 79 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 45 | 79 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 45 | 79 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 46 | 44 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 47 | 37 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 48 | 88 | M | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 49 | 72 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 50 | 83 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 51 | 84 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 52 | 65 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 52 | 65 | F | Yes | Awake | |

| 53 | 75 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 54 | 31 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 55 | 36 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 56 | 85 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 57 | 85 | F | No | Stuporous/comatose | Oral automatisms |

| 58 | 77 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 59 | 57 | M | Yes | Awake | |

| 60 | 25 | F | Yes | Awake | Aphasia |

| 60 | 25 | F | Yes | Awake | Aphasia |

| 61 | 62 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 62 | 77 | F | Yes | Drowsy | Orofacial automatisms |

| 62 | 77 | M | Yes | Stuporous/comatose | |

| 62 | 76 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 63 | 45 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 64 | 66 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 65 | 85 | M | No | Awake | |

| 66 | 75 | M | No | Drowsy | Leg myoclonus |

| 67 | 21 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 68 | 78 | M | No | Drowsy | |

| 69 | 32 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 70 | 56 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 71 | 75 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 71 | 75 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 72 | 67 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 73 | 50 | F | No | Drowsy | |

| 74 | 67 | F | No | Drowsy | 3 episodes of stammering |

| 75 | 63 | F | Yes | Drowsy | |

| 75 | 63 | F | Yes | Drowsy |

F: female; M: male.

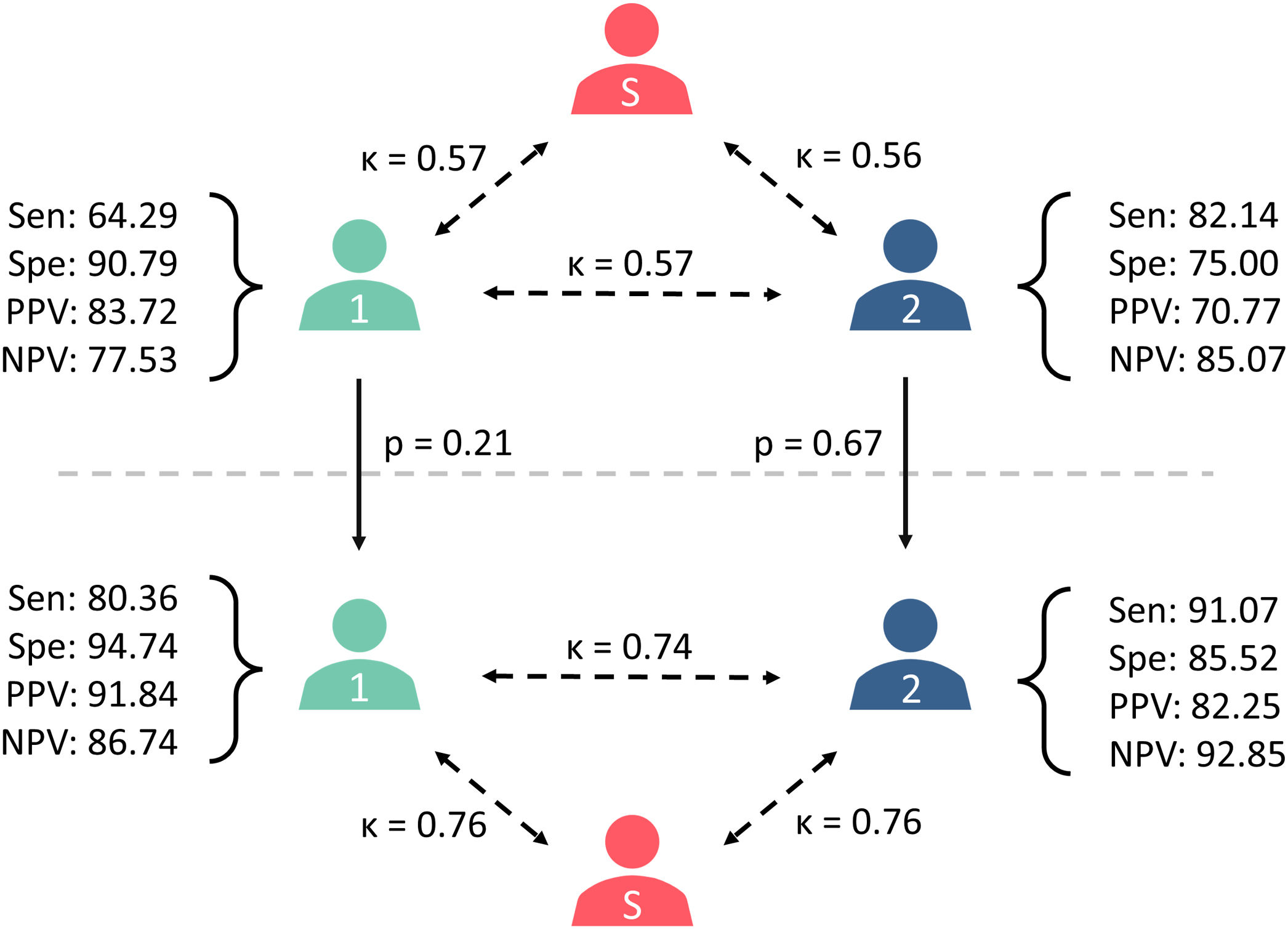

In the retrospective, blind analysis of EEG recordings, reviewer 1 (B.E.) classified 43 recordings as compatible with definite NCSE (33%) and 89 as no NCSE (67%). These results present a sensitivity of 64.29%, a specificity of 90.79%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 83.72%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 77.53%. On the other hand, reviewer 2 (J.I.) classified 65 EEG recordings as definite NCSE (49%) and 67 as no NCSE (51%), resulting in a sensitivity of 85.14%, specificity of 75.00%, PPV of 70.77%, and NPV of 85.07%. The Cohen's kappa coefficient between the reference standard and the reviewers was k=0.57, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.43–0.71, for reviewer 1 and k=0.56 (95% CI, 0.42–0.68) for reviewer 2; the correlation coefficient between the 2 reviewers was k=0.57 (95% CI, 0.43–0.70).

Informed EEG interpretationAfter reviewing the patients’ clinical and demographic information, the reviewers were asked to reclassify the EEG recordings and issue a definitive diagnosis. Reviewer 1 classified 49 recordings as compatible with NCSE (37%), ruling out a diagnosis of NCSE in 83 cases (63%); this yielded a sensitivity of 80.36%, specificity of 94.74%, PPV of 91.84%, and NPV of 86.74%. Reviewer 2 classified 62 EEG recordings as NCSE (47%) and 70 recordings as no NCSE (53%), with a sensitivity of 91.07%, specificity of 85.52%, PPV of 82.25%, and NPV of 92.85%. The Cohen's kappa coefficient between the reference standard and the reviewers was k=0.76 (95% CI, 0.64–0.87) for reviewer 1 and k=0.76 (95% CI, 0.65–0.86) for reviewer 2; the correlation coefficient between the 2 reviewers was k=0.74 (95% CI, 0.63–0.85) (Fig. 3).

Diagram summarising the results of the study: differences in the diagnoses issued by reviewers 1 and 2, as well as between each reviewer and the reference standard (S), in the blind (above) and informed assessments (below). Cohen's kappa coefficients are presented beside the dashed arrows, and McNemar's P values are presented beside the continuous arrows. NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; Sen: sensitivity; Spe: specificity.

Access to patient data led the reviewers to change the diagnosis in several cases. Reviewer 1 changed diagnosis from definite NCSE to no NCSE in 5 patients, and from no NCSE to definite NCSE in 11 patients. Reviewer 2 reclassified 13 EEG recordings from definite NCSE to no NCSE, and 10 recordings from no NCSE to definite NCSE. Overall, knowledge of the patients’ clinical status led reviewer 1 to change diagnosis in 16 recordings (12%) and reviewer 2 to change diagnosis in 23 recordings (17%).

The McNemar's test revealed no statistically significant differences for either reviewer in the diagnoses issued reviewing the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics, with a P value of .21 (result: 1.56) for reviewer 1, and a P value of 0.67 (result: 0.17) for reviewer 2 (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis study analysed the impact of patient information on EEG interpretation in cases of suspected NCSE. Because this condition presents with subtle clinical manifestations, or may even be asymptomatic,2–4 EEG is an essential tool for diagnosis and management.19–21 On the other hand, there is a trend in the field of EEG towards automatic interpretation, including the use of automated systems for detecting seizures and epileptiform patterns.13,14 These tools are frequently used at centres lacking physicians trained in EEG interpretation, or as an initial approach in emergency situations (akin to the automated external defibrillators used in ambulances).22,23 Nevertheless, it is important to interpret EEG recordings within the clinical context of each patient, as this information may have a significant impact on diagnosis. This may be due to the fact that there are multiple EEG patterns of uncertain significance,24–26 as well as clinical situations in which there is no consensus on the interpretation of EEG (i.e., in comatose patients27). Therefore, 2 very similar EEG recordings can lead to different diagnoses depending on the patient's clinical status.

In this study, 2 independent reviewers classified EEG recordings as compatible with either NCSE or no NCSE, in 2 different scenarios. In the first scenario, they classified the recordings without any demographic and clinical information, whereas in the second, they had access to all this information before reviewing the EEG recordings.

Blind EEG interpretation yields underwhelming performanceThe 2 reviewers interpreted EEG recordings similarly in the blind condition. Differences arose from their different approach to the lack of clinical and demographic information: while one reviewer chose a more conservative approach, the other argued that more patterns could be interpreted as ictal due to the lack of clinical data. These differing interpretations led to mirrored performance metrics, with the more conservative approach achieving high specificity and comparatively lower sensitivity, and the opposite for the other reviewer. However, both reviewers showed moderate agreement with the reference standard. These values are lower than those reported in studies evaluating the agreement between independent reviewers and the modified Salzburg criteria.28–32 This may be explained by the fact that the reviewers were not able to fully apply the modified Salzburg criteria during blind EEG interpretation, as they were unable to assess the presence of subtle clinical ictal phenomena or improvement with antiepileptic drugs due to their lack of access to clinical data.

EEG complemented with clinical data improves interpretationAccess to patient clinical and demographic information increased the reviewers’ ability to correctly classify EEG recordings. Although an increase was observed in all performance metrics and inter-rater agreement, these changes did not yield statistically significant differences, probably due to our relatively small sample size. After full application of the modified Salzburg criteria, inter-rater agreement is comparable to the values reported by other authors,28–32 confirming that clinical information is crucial for the correct application of the criteria.

History of epilepsy and level of consciousness are directly linked to diagnosis of NCSEAmong the data obtained from each patient, we found a statistically significant relationship between history of epilepsy and diagnosis of NCSE. In other words, the probability of a positive diagnosis of NCSE is higher in patients with known epilepsy in our cohort. Interestingly, we found a higher proportion of patients with history of epilepsy than reported in the literature.33–35 This discrepancy may be attributed to a potential diagnostic bias, with clinicians being more likely to suspect NCSE and pursue EEG confirmation in patients with known epilepsy, while potentially overlooking similar presentations in those without history of seizures. Similarly, we found a strong correlation between level of consciousness and the probability of this finding being due to NCSE. While the level of consciousness is an important factor in assessing NCSE, this finding alone is not sufficient for diagnosis, as an altered level of consciousness may be due to multiple causes.5,15,16 This suggests that a positive diagnosis of NCSE is more likely in patients presenting somnolence or stupor/coma than in those with a normal level of consciousness, when there is already suspicion of NCSE. We hypothesise that these factors may play a role in the automatic detection of NCSE; automatic detection systems should incorporate these input variables for the interpretation of EEG recordings.

Limitations and pitfallsThe main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature. Regardless of the amount and quality of information given to the reviewer retrospectively, evaluating EEG recordings at the time of assessment always achieves superior diagnostic accuracy. Real-time access to video footage, which provides a clinical context for EEG findings, is essential. Other advantages of analysing the EEG recording in real time include the possibility of examining the patient or performing an antiepileptic drug trial (which may be crucial in the diagnosis of NCSE, according to the modified Salzburg criteria).

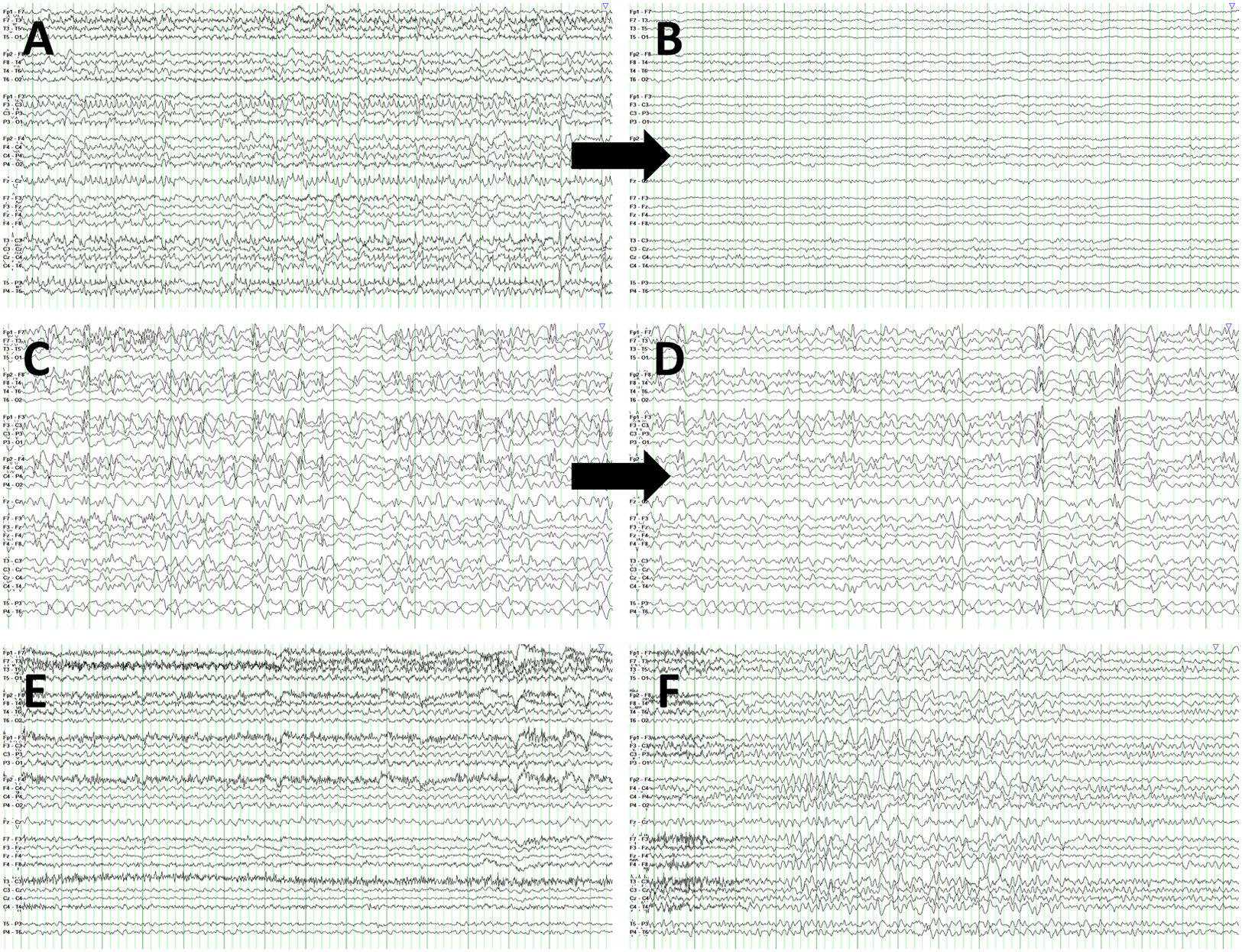

Several factors account for the majority of false negative and false positive results. The lack of information about antiepileptic drug trials and insufficient data on level of consciousness between episodes explained most false negatives. This would not have been an issue for the physician at the time of the original observation. Furthermore, in the event of ambiguous EEG findings, diagnosis was based on previous recordings. However, the reviewers participating in our study were not given the option to review previous EEG recordings from a particular patient. On the other hand, some false positive diagnoses were issued in patients displaying rhythmic patterns, such as frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity (Fig. 4). Nonetheless, once the reviewers had access to the patients’ clinical information, the rate of correct diagnoses increased to values in line with the literature.28–32 This highlights the need to involve physicians in the clinical evaluation of patients with suspected NCSE due to the potential errors associated with blind EEG assessment.

EEG recordings corresponding to false negatives and false positives. (A) False negative. Patient 34 presents rhythmic spikes predominantly in the vertex, coinciding with generalised subtle jerks. (B) EEG from the same patient, following intravenous administration of 0.5mg clonazepam. (C) False negative. EEG recording from patient 52 shows bifrontal spike, spike-wave, and polyspike-wave discharges, with no clinical manifestations. (D) EEG recording from the same patient, following intravenous administration of 0.5mg clonazepam. (E) False positive. Patient 47 shows background activity slowing, sometimes following a rhythmic pattern, without clear progression and with no clinical manifestations. (F) EEG recording from patient 18 revealing frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity.

EEG is a versatile tool employed in a wide range of situations, and is especially useful in the diagnosis of NCSE with subtle or no motor manifestations.1,8 With the proliferation of automatic seizure detection systems,13,14 it is imperative to remember the importance of demographic and clinical data when interpreting an EEG recording. This study shows the difference between blind EEG interpretation and EEG interpretation complemented with patient clinical and demographic data, demonstrating that the clinical context is essential in the diagnosis of NCSE.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors has potential conflicts of interest to be disclosed.