Cutaneous allodynia has been described in primary headaches. The 12-item Allodynia Symptom Checklist (ASC-12) is a valid, reliable scale for assessment in the population with migraine. No Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 is currently available, so we performed the cross-cultural adaptation and validation of a Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 in patients with primary headaches.

MethodsThis validation study included 131 patients who attended a single consultation at the headache unit and completed 3 self-administered scales: the ASC-12, the self-reported version of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs pain scale, and the ID Pain questionnaire. Patients’ diagnosis was confirmed by a neurologist specialized in headache management, according to the diagnostic criteria of the third edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders. A linguistic adaptation and a psychometric analysis were performed, assessing discriminative, convergent, and construct validity, as well as reliability and floor and ceiling effects.

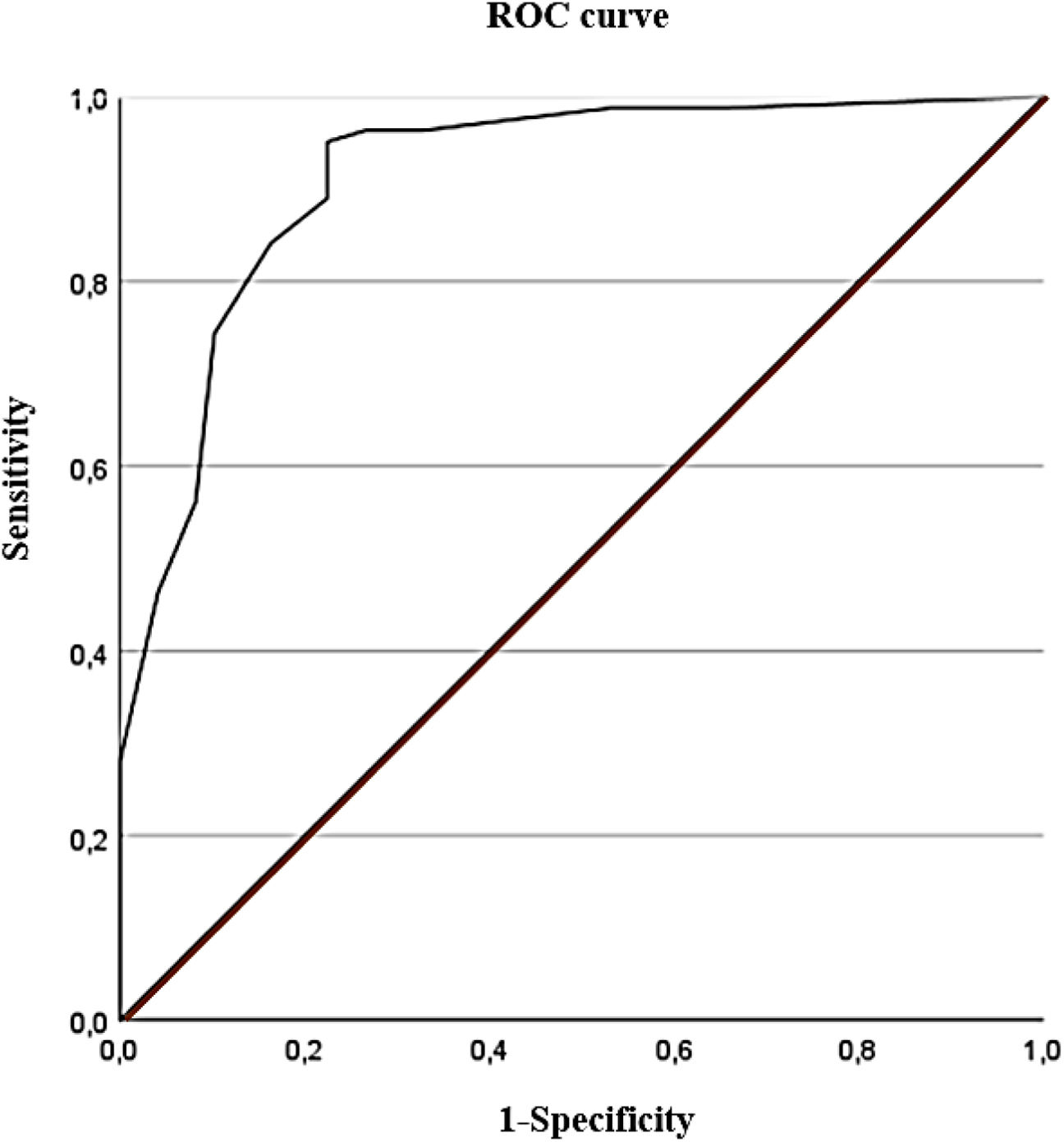

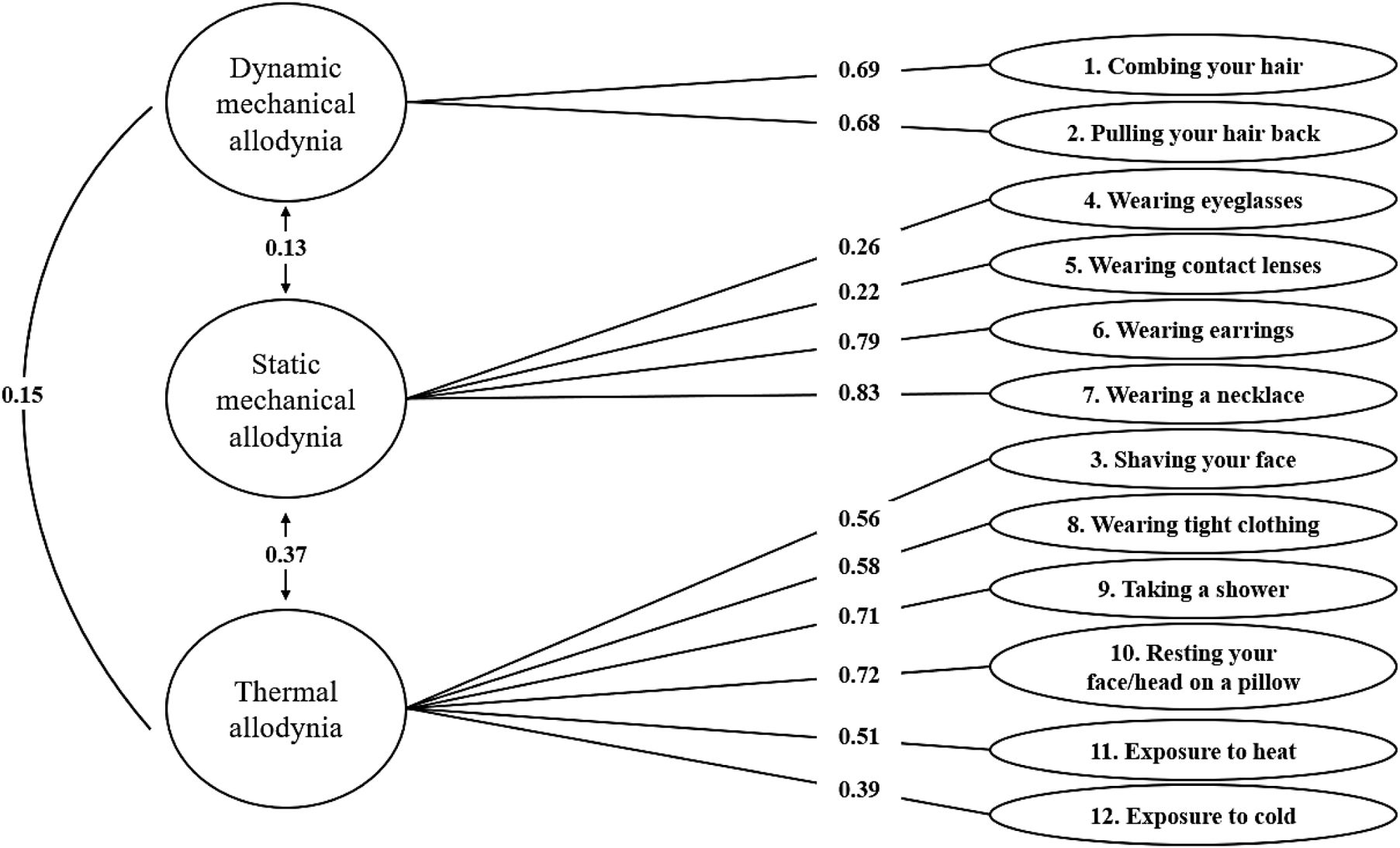

ResultsThe scale presented high diagnostic accuracy (receiver operating characteristic curve value of 0.91; 95% confidence interval, 0.86–0.97; P<.001). Pearson correlations indicated moderate to strong correlations between scales. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test yielded a value of 0.72. The Bartlett test was significant (Chi-square value of 440.887; P<.001). The construct validity study identified 3 factors (thermal, mechanical static, and dynamic allodynia). Internal consistency was satisfactory (Cronbach alpha value of 0.78; 95% confidence interval, 0.72–0.83). No floor or ceiling effect was detected.

ConclusionsThe Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 for patients with primary headaches is a valid, reliable tool that can be implemented in the clinical and research settings.

Las cefaleas primarias pueden cursar con alodinia cutánea. El cuestionario de síntomas de alodinia (Allodynia Symptom Checklist [ASC-12]) es una herramienta válida y fiable para evaluar los síntomas de alodinia en los pacientes con migraña. Actualmente no existe una versión en español, por lo que hemos realizado una adaptación transcultural y validación de una versión en español de la escala ASC-12 en los pacientes con cefaleas primarias.

MétodosEste estudio de validación reclutó a 131 pacientes que, en una única consulta en la unidad de cefaleas, completaron 3 escalas autoadministradas: la ASC-12, la escala autoadministrada de Evaluación de Signos y Síntomas Neuropáticos de Leeds y el cuestionario ID-Pain. Un neurólogo especialista en cefaleas confirmó el diagnóstico en función de los criterios diagnósticos de la tercera edición de la Clasificación Internacional de Cefaleas. Se realizó una adaptación lingüística y un análisis psicométrico, analizando la validez discriminante, convergente y de constructo, además de la fiabilidad y los efectos suelo y techo.

ResultadosLa escala presenta una alta precisión diagnóstica (AUC: 0,91; IC 95%: 0,86-0,97; p<0,001). El coeficiente de Pearson indica una correlación moderada a fuerte entre las escalas. La prueba de Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin arrojó un valor de 0,72. La prueba de Bartlett obtuvo un resultado significativo (valor del test de Chi-cuadrado de 440,887; p<0,001). El análisis de validez de constructo identificó 3 factores (alodinia térmica, alodinia estática y alodinia dinámica). La escala presentó una consistencia interna aceptable (alfa de Cronbach de 0,78; IC 95%; 0,72-0,83). No se observó efecto suelo ni efecto techo.

ConclusionesLa versión española de la ASC-12 para los pacientes con cefaleas primarias es una herramienta válida y fiable para su uso tanto en la práctica clínica como en investigación.

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines cutaneous allodynia as the perception of pain in response to non-painful stimuli.1 Depending on the type of stimulus, cutaneous allodynia can be subclassified into static mechanical, dynamic mechanical, and thermal allodynia.2,3 Cutaneous allodynia in response to mechanical or thermal stimuli has been described in a wide variety of pain disorders.4,5

In recent decades, the presence of cutaneous allodynia in patients with primary headaches has been reported in the scientific literature.6–11 In addition, cutaneous allodynia has been identified as a risk factor for migraine chronification12 and has been associated with psychiatric comorbidity.6,13 Its estimated prevalence is 53–63% in the population of patients with migraine3,14 and 36–40% in patients with cluster headache.6,8 Research suggests that the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying allodynia in patients with migraine are linked to the sensitization of second- and third-order neurons, with the spinal trigeminal nucleus (caudal portion) being particularly relevant.9,15,16

Developed by a German research group studying neuropathic pain, the current gold standard for the diagnosis of cutaneous allodynia is quantitative sensory testing (QST), which is based on the application of mechanical and thermal stimuli to the skin that, under normal conditions, should not generate pain.17,18 Thermal stimuli are usually applied by means of thermometric tests, whereas mechanical stimuli are applied by means of different instruments validated by standardizing the pressure they exert on the skin.17,19 However, somatosensory examination requires a lot of time, training, and materials that are not available to the clinician, hindering the use of this method in clinical practice.20 Moreover, in acute headache attacks it is often difficult to perform this type of examination, and some stimuli may occasionally exacerbate headache symptoms.8 To overcome these diagnostic limitations, the 12-item Allodynia Symptom Checklist (ASC-12) was designed. The original version of the ASC-12 was developed by Lipton et al.3 in 2008. The scale includes 12 items related to the frequency of pain occurrence during the performance of activities that normally should not produce pain, and serves to detect cutaneous allodynia and to estimate its severity in migraine patients.3 To date, the ASC-12 has been translated and validated into Portuguese, German, and Turkish.21–23 However, there is currently no validation of the ASC-12 into Spanish. For this reason, the aim of this study was to perform a cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the ASC-12 into Spanish, demonstrating its validity and reliability for use in patients with primary headaches.

MethodsDesignThis is a cross-sectional observational study conducted in collaboration with the headache unit of Hospital Fundación Jiménez Díaz and Hospital Universitario de La Paz (Madrid, Spain). This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of both institutions (PI-5213). Sampling was consecutive, and patients who met the selection criteria attended a single consultation at the headache unit, where they completed the 3 self-administered scales: the ASC-12, the self-reported version of the Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) pain scale, and the ID Pain questionnaire. The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS)24 was applied in a separate room by a researcher blinded to the patient's diagnosis and scores on the other scales. Finally, the same researcher ensured that patients provided demographic and clinical data. Patient recruitment and data collection were carried out from April to October 2023. The sample size was estimated based on a subject-to-item ratio of 10:1, as recommended in the literature25; thus, we determined a sample size of at least 120 patients with primary headaches, which also satisfied the Consensus-based Standards for the Selection of Health Status Measurement Instruments (COSMIN) recommendations.26

The study sample comprised 131 patients with primary headaches diagnosed by a neurologist specialized in the management of headache disorders, according to the criteria of the latest version of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3).27 We included men and women between 18 and 65 years of age with a neurological diagnosis of primary headache (ICHD-3), who were able to understand the questionnaires and the Spanish language. We excluded patients who had an acute headache attack during the measurements, and those with neurological and rheumatic comorbidities, cancer, or a psychiatric comorbidity that might affect their comprehension and completion of the questionnaires.

Instrument descriptionASC-12The ASC-12 is a scale validated in English by Lipton et al.3 for the examination of cutaneous allodynia in patients with migraine, based on a previous work by Jakubowski et al.18 It consists of 12 items related to the frequency of the occurrence of pain or unpleasant sensations in the presence of stimuli generated by activities that do not normally produce pain.1,3 It contains 5 response options: does not apply to me (0 points), never (0 points), rarely (0 points), less than half of the time, (1 point) and half of the time or more (2 points). The scale establishes 4 degrees of severity of cutaneous allodynia: absent (0–2), mild (2–5), moderate (6–8), and severe (≥9).3 In addition, the authors were able to differentiate the 12 items, classifying them according to 3 factors related to the dimensions of allodynia: static mechanical (items 4–8), dynamic mechanical (items 1 and 2), and thermal (items 3 and 9–12).3

S-LANSSThe self-reported version of the S-LANSS is a self-administered questionnaire used to classify patients with respect to the presence or absence of neuropathic pain.28 Both the original version and its validated Spanish-language version include 7 items.29 The possible answers to each item are dichotomous (yes/no), with a total score ranging from 0 to 24 points. A score of 12 points or higher suggests the presence of neuropathic pain.

ID Pain questionnaireThe ID Pain questionnaire is another self-reported scale that seeks to classify patients according to the type of pain they suffer, i.e., neuropathic or nociceptive pain.30 As in the S-LANSS scale, the possible answers are dichotomous (yes/no), with affirmative answers scoring one point, with the exception of the last item (item 6), which is scored −1. The total score ranges from −1 to 5 points. A score of 3 points or higher reflects pain with neuropathic characteristics.31

Numerical Rating ScaleThe Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) is a valid and reliable measure of pain intensity.24 Patients mark the score that best represents the intensity of their pain (0: absence of pain; 10: worst pain imaginable).

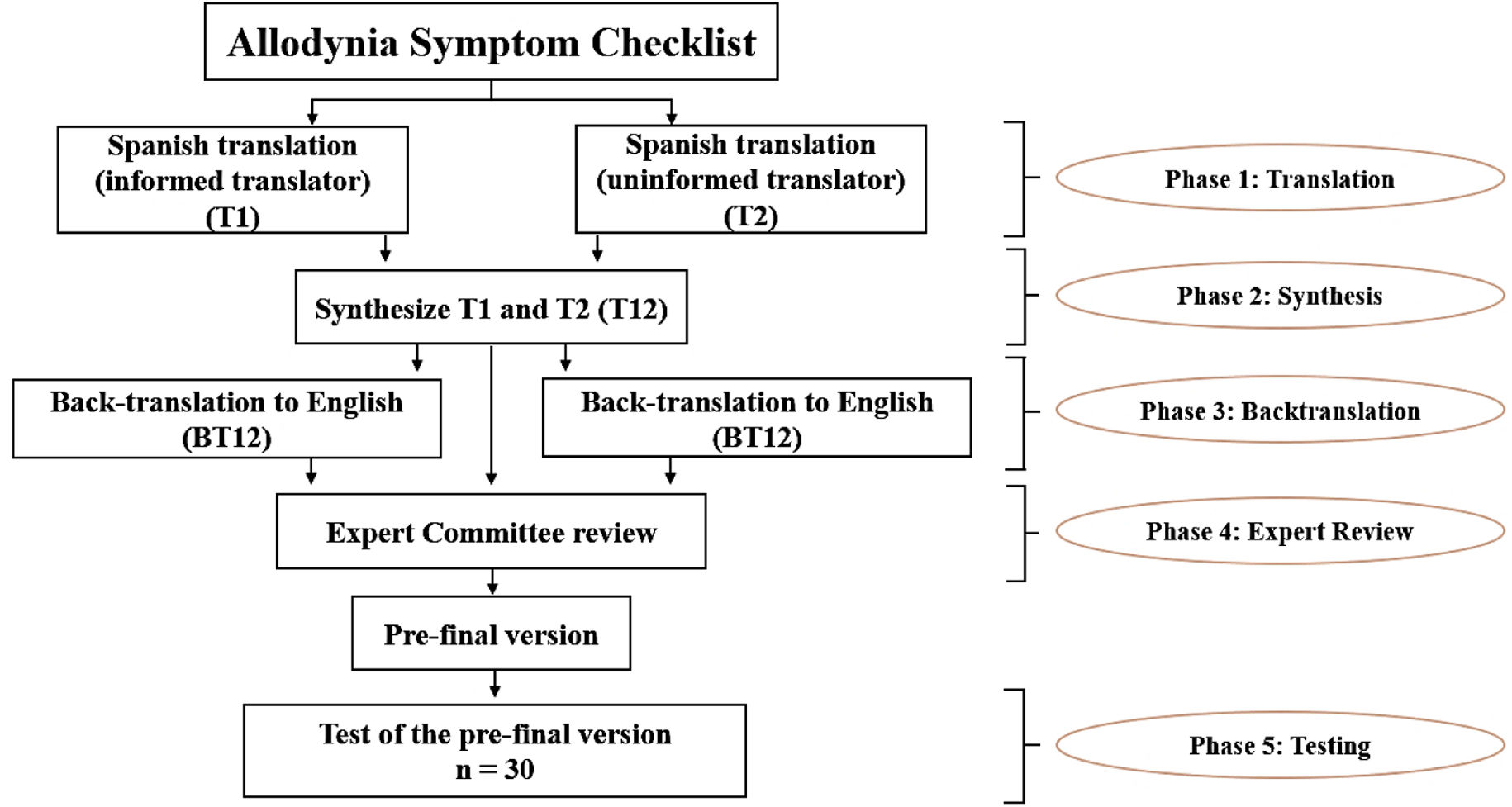

Linguistic adaptationThe adaptation of the ASC-12 scale to Spanish was carried out in 5 phases.32 In phase 1, 2 bilingual native Spanish speakers independently translated the scale into Spanish. One of them was previously informed about the concept of allodynia and the purpose of the scale, while the other translator was not aware of this information. This was done to prevent translator 2 from being influenced by this conceptual information, so that the translation would reflect the everyday use of Spanish in the population. In phase 2, both translators, accompanied by a third observer, synthesized the 2 translated versions. In phase 3, 2 bilingual native English speakers, blinded to the process carried out in phases 1 and 2, back-translated the text into English; this phase is conducted in order to identify inconsistencies or conceptual errors that may have occurred in phases 1 and 2. In phase 4, a committee of pain experts consisting of professionals from different disciplines (neurologists, physiotherapists, psychologists, and linguists) synthesized the translated and back-translated versions, taking into account their semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence. This phase resulted in the generation of the pre-final version of the scale, which was later piloted with 30 patients with primary headaches (phase 5), who were asked to comment on its comprehensibility and relevance and invited to make other comments they deemed appropriate. This final phase was conducted between February and March 2023. Fig. 1 provides a schematic illustration of the linguistic adaptation process.

Statistical and psychometric analysisThe statistical and psychometric analyses detailed below were performed using the SPSS software (version 29.0; IBM, New York, USA). Statistical significance was established at a P-value<.05, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. No data were lost during collection and processing.

Discriminant validityDiscriminant validity was assessed by comparing the ability of the ASC-12 to detect the presence of cutaneous allodynia against the criterion variable. The criterion variable selected was diagnosis of neuropathic pain established by S-LANSS, because the convergent correlation with ASC-12 was superior to the correlation between the ASC-12 and the ID Pain questionnaire (see Results section). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve value was calculated, and the ROC curve was generated to determine the proportion of correctly classified patients with primary headaches. The reference values used to interpret the data obtained were as follows: high diagnostic accuracy for results ≥0.9, moderate for values of 0.71–0.89, low for values of 0.51–0.7, and due to chance for values ≤0.5.33 The optimal cut-off point was then established by calculating the Youden index. Sensitivity and specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and positive and negative predictive values were also calculated. In addition, the Cohen's kappa concordance index was used to evaluate the degree of agreement in diagnostic classification between the ASC-12 and the S-LANSS. Cohen's kappa was considered almost perfect for values ≥0.8, considerable for values of 0.60–0.80, moderate for values of 0.40–0.60, fair for values of 0.20–0.40, and poor for values <0.20.34 In general, scores >0.70 are considered to indicate a good degree of agreement.35

Convergent validityFor the analysis of convergent validity, the Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated between the total scores on the ASC-12 and on the other questionnaires used. Values >0.6 were considered to reflect a strong correlation, with values of 0.4–0.6 interpreted as a moderate correlation and <0.4 as a weak correlation.35

Construct validityTo verify the 3-dimensional factor structure reported in the original version of the scale,3 a factor analysis was conducted using the unweighted least-squares extraction method and the Oblimin rotation method with Kaiser normalization. To assess the relevance of performing factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test was performed. This test evaluates the degree of multicollinearity, with values ranging between 0 and 1. The degree is interpreted as excellent for values of 0.9–1, good for values of 0.8–0.9, acceptable for values of 0.7–0.8, mediocre for values of 0.6–0.7, bad for values of 0.5–0.6, and unacceptable for values <0.5.36 To test the hypothesis that the correlation matrix was an identity matrix, the Bartlett’ test of sphericity was performed. The values that could reflect the relevance of the factor analysis were P<.05.37

ReliabilityThe Cronbach’ alpha statistic was used to analyze the internal consistency of the ASC-12 scale. The ASC-12 would be considered to have adequate internal consistency if Cronbach’ alpha values were ≥0.7.35,38,39 In addition, ceiling and floor effects were considered to exist in the event that the percentage of patients reporting the lowest and highest possible score on the ASC-12 scale was ≥15%.35

ResultsLinguistic adaptationIn the cross-cultural adaptation and translation, some words and expressions from the original version were modified to improve the comprehensibility of the scale. The initial question “How often do you experience increased pain or an unpleasant sensation on your skin during your most severe type of headache when you engage in each of the following?” was translated as “Cuando usted tiene dolor de cabeza: ¿con qué frecuencia siente que le aumenta el dolor o una sensación desagradable al hacer lo siguiente?” Item 8 “wearing tight clothing” was made explicit by providing an example: “al llevar ropa ceñida en la cara o cabeza (p. ej. un gorro)” (English: “wearing tight clothing (e.g., a cap)”). Item 9 “taking a shower (when shower water hits your face)” was made explicit by expanding the example “al ducharse (cuando cae agua sobre su cabeza y cara)” (English: “when taking a shower (when water hits your head and face)”). Once these adaptations were performed, the pre-final version of the scale was produced by the expert committee. When testing the pre-final version, no comments regarding comprehensibility or relevance were made by the sample recruited for the pre-final testing (n=30). For this reason, the pre-final version was considered the final Spanish-language version of the ASC-12, which was subsequently used for the psychometric analysis (Supplementary material).

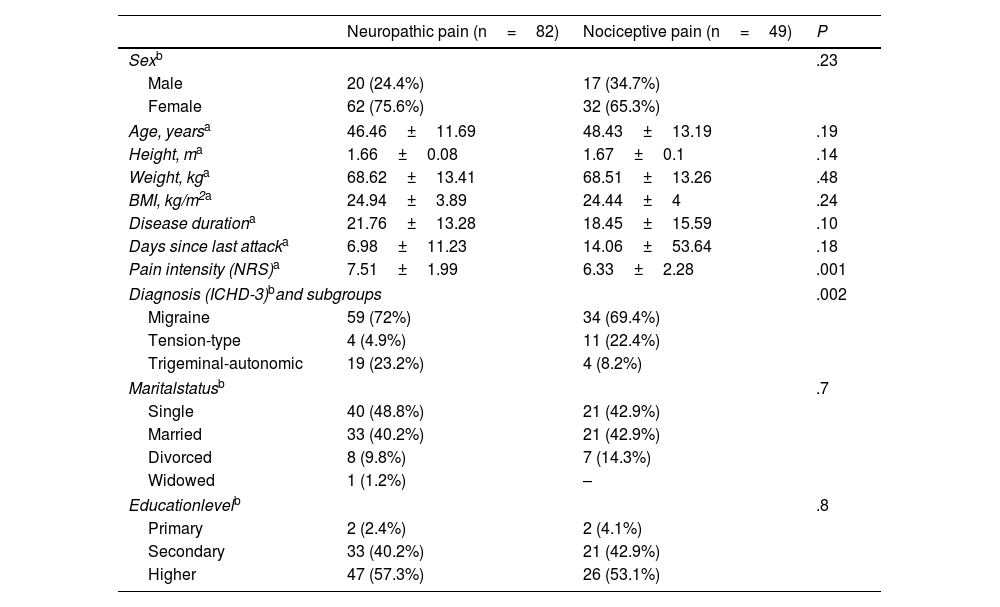

Psychometric propertiesA total of 131 patients with primary headaches were included in the study. Their mean age was 47.20 (SD, 12.26) years and there was a higher proportion of women than men (71.8% vs 28.2%). The sample was classified according to S-LANSS scores: 82 patients presented neuropathic and 49 nociceptive pain. Both groups presented homogeneous demographic variables as there were no statistically significant differences (P>.05). However, the neuropathic pain group presented greater pain intensity than the nociceptive pain group (P=.001). There were also significant differences in the types of pain between the different primary headache diagnoses (P=.002) (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical variables of patients with primary headaches with neuropathic and nociceptive pain.

| Neuropathic pain (n=82) | Nociceptive pain (n=49) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexb | .23 | ||

| Male | 20 (24.4%) | 17 (34.7%) | |

| Female | 62 (75.6%) | 32 (65.3%) | |

| Age, yearsa | 46.46±11.69 | 48.43±13.19 | .19 |

| Height, ma | 1.66±0.08 | 1.67±0.1 | .14 |

| Weight, kga | 68.62±13.41 | 68.51±13.26 | .48 |

| BMI, kg/m2a | 24.94±3.89 | 24.44±4 | .24 |

| Disease durationa | 21.76±13.28 | 18.45±15.59 | .10 |

| Days since last attacka | 6.98±11.23 | 14.06±53.64 | .18 |

| Pain intensity (NRS)a | 7.51±1.99 | 6.33±2.28 | .001 |

| Diagnosis (ICHD-3)band subgroups | .002 | ||

| Migraine | 59 (72%) | 34 (69.4%) | |

| Tension-type | 4 (4.9%) | 11 (22.4%) | |

| Trigeminal-autonomic | 19 (23.2%) | 4 (8.2%) | |

| Maritalstatusb | .7 | ||

| Single | 40 (48.8%) | 21 (42.9%) | |

| Married | 33 (40.2%) | 21 (42.9%) | |

| Divorced | 8 (9.8%) | 7 (14.3%) | |

| Widowed | 1 (1.2%) | – | |

| Educationlevelb | .8 | ||

| Primary | 2 (2.4%) | 2 (4.1%) | |

| Secondary | 33 (40.2%) | 21 (42.9%) | |

| Higher | 47 (57.3%) | 26 (53.1%) | |

As no data were lost, the total sample (n=131) was used for the calculation and evaluation of discriminant validity, convergent validity, construct validity and internal consistency (reliability).

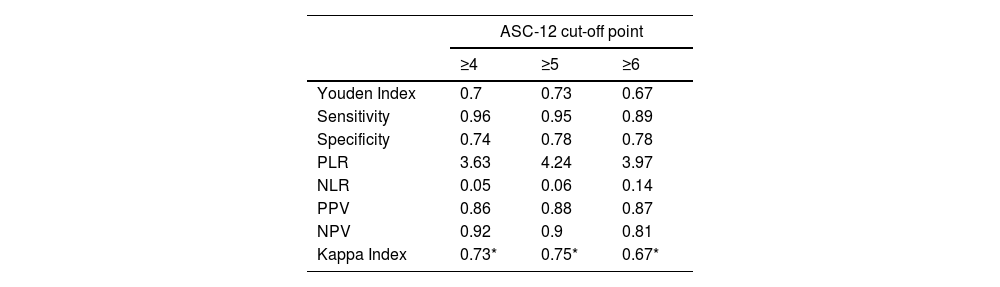

Discriminant validityIn this study, the diagnosis established according to the S-LANSS scale was used as the criterion variable. The discriminant validity analysis showed that the best cut-off point was a value of ≥5 points on the ASC-12 scale. The ROC value obtained was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.86–0.97; P<.001), indicating a high diagnostic accuracy (Fig. 2). Likewise, the cut-off of ≥5 points on the ASC-12 scale presented the highest Youden index (0.73), which implies the highest sensitivity and specificity values (95% and 78%, respectively). Finally, a kappa coefficient of 0.75 (P<.001) was obtained, which represents a considerable level of diagnostic agreement with the S-LANSS scale. Table 2 shows the best diagnostic indicators associated with the best cut-off points and the highest Youden index values.

Diagnostic indicators of the Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 with different cut-off points for detecting allodynia.

| ASC-12 cut-off point | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥4 | ≥5 | ≥6 | |

| Youden Index | 0.7 | 0.73 | 0.67 |

| Sensitivity | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| Specificity | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| PLR | 3.63 | 4.24 | 3.97 |

| NLR | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.14 |

| PPV | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.87 |

| NPV | 0.92 | 0.9 | 0.81 |

| Kappa Index | 0.73* | 0.75* | 0.67* |

PLR: positive likelihood ratio; PPV: positive predictive value; NLR: negative likelihood ratio; NPV: negative predictive value.

The Pearson correlation coefficients obtained were 0.74 between the ASC-12 and the S-LANSS (P<.001), and 0.55 between the ASC-12 and the ID Pain questionnaire (P<.001). These values reflect strong and moderate correlation, respectively, thus determining adequate convergent validity.

Construct validityThe factor structure of the scale was composed of 3 factors, as in the original version. The factors were identified by means of a factor analysis using the unweighted least-squares extraction method and the Oblimin rotation method, which explained 43.8% of the variance. The KMO test yielded a value of 0.72, indicating an acceptable degree of multicollinearity. On the other hand, the Bartlett test score was significant (Chi-square value of 440.887; P<.001). The resulting factor weight for each item of the Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 is shown in Fig. 3.

Factor structure of the Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 according to the confirmatory factor analysis. The standardized coefficients represent the individual contribution of each item.

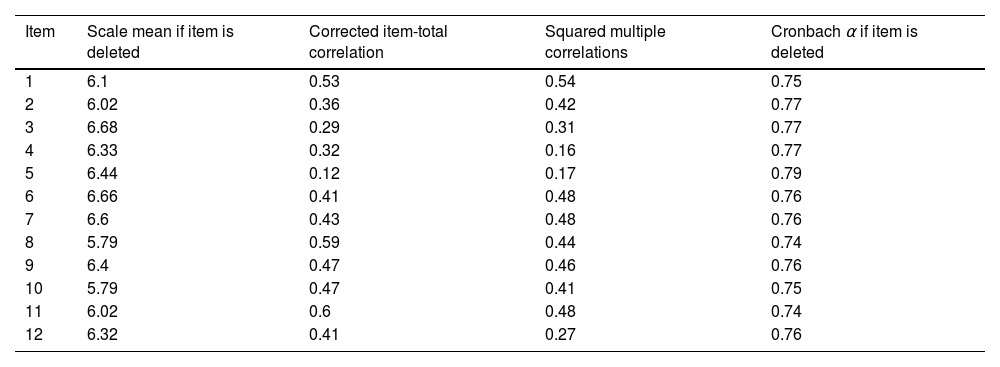

The internal consistency of the scale was analyzed using the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the item-total score correlation, which was 0.78 (95% CI, 0.72–0.83), reflecting satisfactory internal consistency. This result implies that the ASC-12 scale is reliable in classifying patients with primary headaches in relation to the presence or absence of cutaneous allodynia. Table 3 shows other results, including the mean ASC-12 score and the Cronbach alpha if any of the items is eliminated. Finally, the percentage of patients reporting the lowest (13.8%) and highest (0.8%) possible ASC-12 scores was <15%, thus ruling out the existence of floor and ceiling effects, respectively.

Corrected item-total between ASC-12 item.

| Item | Scale mean if item is deleted | Corrected item-total correlation | Squared multiple correlations | Cronbach α if item is deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 6.1 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.75 |

| 2 | 6.02 | 0.36 | 0.42 | 0.77 |

| 3 | 6.68 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.77 |

| 4 | 6.33 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.77 |

| 5 | 6.44 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.79 |

| 6 | 6.66 | 0.41 | 0.48 | 0.76 |

| 7 | 6.6 | 0.43 | 0.48 | 0.76 |

| 8 | 5.79 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.74 |

| 9 | 6.4 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.76 |

| 10 | 5.79 | 0.47 | 0.41 | 0.75 |

| 11 | 6.02 | 0.6 | 0.48 | 0.74 |

| 12 | 6.32 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.76 |

This study succeeded in validating the Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 scale for patients with primary headaches. The scale demonstrates adequate levels of validity and reliability, allowing its use in the clinical and research settings. This study enables the ASC-12 to be used to detect the presence or absence of allodynia, and as a clinical follow-up variable. The need for this tool and its validation is justified by the fact that there are studies using the original version to measure cutaneous allodynia in patients with headaches other than migraine.6–8 Moreover, the optimal cut-off point used in some studies to detect cutaneous allodynia (≥3)6–8 is not based on a specific statistical calculation performed for this purpose.3 In fact, the authors of the original version established 4 categories of cutaneous allodynia severity (absent, mild, moderate, and severe), and noted that this type of classification was somewhat arbitrary.3 In the present study, the optimal cut-off point for detecting cutaneous allodynia in patients with primary headaches was a score of ≥5. This cut-off point represents a more demanding criterion than the one used in the literature to detect cutaneous allodynia,6–8 and may therefore be expected to exhibit a higher rate of true positives, which should be corroborated in future work by comparing the psychometric properties against the gold standard (QST). Despite reaching moderate-high levels of sensitivity and specificity in the detection of cutaneous allodynia (95% and 78%, respectively), it should be noted that these values were obtained using the S-LANSS as the criterion variable, and should therefore be interpreted with caution.

Through this work, we sought to create a Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 scale to be administered to Spanish-speaking patients with migraine and trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias (which amount to millions of people). The results of this study, inherent to the high presence of allodynia in patients with trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, are aligned with those of other authors who previously reported the presence of cutaneous allodynia in patients with cluster headache.6,8,10

At present, there is no official validation comparing the ASC-12 tool against QST in patients with trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. However, the results found in this study, together with the consistency found between the original validation3 and the underlying study that did compare the ASC-12 with QST,18 support the use of this tool in these clinical populations. In contrast, the recently published German-language validation study found no consistency between the results obtained with the QST and the ASC-12.21 As highlighted by the same authors, this is probably due to the fact that the ASC-12 scale asks questions related to the presence or absence of allodynia during an acute attack, whereas the QST examination is usually not performed during bouts.21

The factor analysis in this study found the same 3 dimensions of cutaneous allodynia (static mechanical, dynamic mechanical, and thermal) as in the original version and in the validations performed in other languages.3,21,23 Moreover, all items matched the previously explored dimension, except for item 8 (“al llevar ropa ceñida en la cara o cabeza,” English “wearing tight clothing on the face or head”), which entered the thermal factor rather than the static mechanical factor. The exact reasons for the behavior of this item are unknown, but this discrepancy may be due to the fact that items may sometimes converge in more than one dimension, since the clothing (e.g., a cap) not only applies a static mechanical stimulus, but may also raise temperature, justifying the convergence of the item in the “thermal allodynia” factor. This is an interesting aspect to consider in the validation of instruments measuring allodynia, since other items could present the same ambiguity. For example, shaving (item 3) and showering (item 9) are considered to converge in the “thermal allodynia” factor but could also converge in the “dynamic mechanical allodynia” factor, or the item “resting your face or head on a pillow,” which is considered a thermal item but might fit in the static mechanical factor. This ambivalence in the behavior of the items should be taken into account for future studies.

As in the original version, and similarly to the Turkish- and German-language versions, the items that contributed the least to the questionnaire were “wearing contact lenses” and “wearing eyeglasses.” On the other hand, the items “wearing a necklace,” “wearing earrings,” “combing one's hair,” and “pulling your hair back” were among the highest contributors, as in the other versions.3,21,23 Similarly, the item “resting your face on a pillow” contributed significantly to the questionnaire, as in the Turkish-language version.23

Clinical implicationsThe identification of cutaneous allodynia in clinical practice is critical, as it has been associated with increased levels of pain, disability, medication intake, decreased quality of life and psychiatric comorbidity. The Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 may be useful in the clinical context because of its short completion time, small number of items, and multidimensionality, as proven by the factor analysis.

LimitationsIt was not possible in this study to calculate test-retest reliability, since the ASC-12 scale was administered only once. This also meant that the standard error of measurement and the minimum detectable change could not be calculated. Future longitudinal studies are needed to determine the responsiveness and test–retest reliability of the tool. Due to the design of our study, the sample size was derived from consecutive sampling, which may have conditioned the results. In addition, the low percentage of patients with only primary education may limit the validity and reliability of the ASC-12 in this subgroup of patients in Spanish-speaking countries. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted with some caution. Furthermore, it was not possible to compare the ASC-12 with the values obtained with QST. Finally, despite the advantages of the ASC-12 tool, it should not be used as a substitute for thorough clinical examination.

Future researchBy validating this scale, future studies will be able to apply it to the millions of Spanish-speaking people worldwide who suffer from primary headaches, thus making it possible to study the prevalence of this type of pain in cohorts among which studies are still scarce (e.g., cluster headache).

ConclusionThe Spanish-language version of the ASC-12 for patients with primary headache is a valid and reliable instrument for both clinical and research use.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors participated substantially in this study. Conception and design: G.B., A.G.M., J.I.E.G.; methodology: G.B., A.G.M., J.I.E.G., J.R.V., A.G.G., M.P.; data acquisition and curation: G.B., A.G.M., J.R.V., A.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation: G.B.; writing—review and editing: G.B., M.P., A.G.M., J.I.E.G.; supervision: A.G.M, J.I.E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standardsWritten informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in this study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Universitario La Paz and Hospital Universitario Fundación Jiménez Díaz (PI-5213, 04/05/2022).

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

The authors of this study would like to acknowledge Matthew Foley-Ryan for his help in the linguistic adaptation process. We also acknowledge the contributions of Jose Luis González and Javier Díaz de Terán, who participated in the expert committee. We also express our gratitude to Javier Bailón Cerezo for his help in designing the methodology of this paper.