Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) hold the highest validity level in effectiveness research. However, there is a growing concern regarding their trustworthiness. We aimed to appraise the quality and reporting of recommendation documents regarding research integrity to describe their contribution towards fostering RCT integrity.

MethodsFollowing prospective registration (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DN93K), searches of electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar) and relevant websites were performed from inception to 30 July 2023 without language limitations. Data extraction and document appraisal using adapted versions of AGREE II, RIGHT and ACCORD checklists were carried out in duplicate. Appraisal data were synthesised as % of the maximum score and documents were classified as: good≥70%, average 50–69%, and poor<50%.

ResultsFrom 1310 citations 14 recommendation documents were selected. Of these, 11 documents (78%) were of poor quality according to all three appraisal checklists. Reviewer agreement was 86–100% regarding the checklist items. The top three documents were: “International multi-stakeholder consensus statement on clinical trial integrity” (score 70% on AGREE II, 96% on RIGHT and 88% on ACCORD); “Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity” (score 51% on AGREE II, 71% on RIGHT and 77% on ACCORD); and “Hong Kong principles for assessing researchers” (score 19% on AGREE II, 57% on RIGHT and 10% on ACCORD).

ConclusionThere is a room from improvement in the quality and reporting of recommendation documents to help fostering RCT integrity. All stakeholders in the RCT lifecycle making concerted efforts to improve trust in evidence-based medicine need robust guidance to underpin research integrity policies and guidelines.

Los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (ECA) aportan el máximo nivel de evidencia en investigación; no obstante, existe una preocupación creciente acerca de su fiabilidad. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la calidad y el reporte de los documentos que hacen recomendaciones respecto a la integridad de la investigación en los ECA y elucidar su contribución al fomento de la misma.

MétodosRevisión sistemática por duplicado en Scopus, PubMed, Google Scholar y sitios web relevantes, desde sus inicios hasta julio del 2023, sin restricción de idioma. Para la evaluación de los documentos se utilizaron versiones adaptadas de las listas de verificación AGREE II, RIGHT y ACCORD y se clasificaron en función del porcentaje de puntuación máxima como: buena≥70%, media 50-69% y baja<50%. Registro prospectivo del protocolo: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DN93K.

ResultadosDe 1.310 referencias se seleccionaron 14 documentos, siendo 11 (78%) de baja calidad por las 3listas de verificación. La concordancia entre los revisores fue del 86-100%. Los documentos con mejores puntuaciones fueron: «International multi-stakeholder consensus statement on clinical trial integrity» (AGREE II: 70%; RIGHT: 96%; ACCORD: 88%); «Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity» (AGREE II: 51%; RIGHT: 71%; ACCORD: 77%) y «Hong Kong principles for assessing researchers» (AGREE II: 19%; RIGHT: 57%; ACCORD 10%).

ConclusionesExiste un amplio margen de mejora en los documentos que efectúan recomendaciones para fomentar la integridad de los ECA. Todas las partes interesadas en el desarrollo de los ECA deben unir sus esfuerzos para proporcionar políticas y directrices de calidad que fomenten la integridad de la investigación y de esta manera aumentar la confianza en la medicina basada en la evidencia.

Randomised clinical trials (RCTs) are the most robust study design to inform clinical practice and policy according to evidence-based medicine principles.1,2 They must be rigorous at all stages of design, execution, and reporting to serve as trustworthy evidence for clinical effectiveness. However, there is a growing number of retractions associated with allegations of scientific misconduct.3 Although the underlying factual basis is disputed,4 it has been claimed that “medicine is plagued by untrustworthy clinical trials” as many RCTs are thought to be “faked or flawed”.5 Moreover, in a self-reported survey conducted among scientists, up to 33.7% admitted questionable research practice.5

Thus, RCTs have become a target for integrity oversight and scrutiny. The need for a coordinated effort by the stakeholder community, including academic institutions and scientific journals is well recognised.6 As healthcare stakeholders, this topic is key in their daily decision-making process. Given that the findings of these RCTs can have a direct impact on patients and healthcare policies, it is crucial to not only understand the recommendation aspects for the proper conduct of RCTs, but also to engage in constructive critical analysis of the recommendations aimed at their optimisation.

The US Office of Research Integrity has estimated that the financial burden of retracted papers accounted for approximately $58 million of loss in direct funding by the US National Institute of Health between 1992 and 2012.6,7 Currently, multiple research integrity recommendations aim to consolidate concepts related to responsible research conduct into documents or statements to help stakeholders address the problem of scientific misconduct.8 To underpin institutional policies and guidelines the quality and reporting of these recommendation documents should be optimal. This is an essential confidence-building feature for all stakeholders associated with research, including funders, universities, oversight agencies, regulators, journals, etc. An evaluation of research conduct codes in Australian universities showed that many responsible research practices were weakly endorsed or not mentioned.9 As these data came from universities active in health and medical research, it is concerning that publication practices related to RCTs like registering protocols were not emphasised.10 A PubMed search using the keyword combination “statement OR consensus OR recommendation” AND ‘research integrity’ in June 2023 produced 2150 citations, none of which were appraisals of the quality and reporting of research integrity recommendation documents. This deficiency is a crucial barrier to the advancement of research integrity in biomedicine in general and in clinical effectiveness research in particular.

Given the above background, our study aimed to evaluate the quality and reporting of recommendation documents concerning research integrity to describe their current contribution towards fostering RCT integrity.

MethodologyThis systematic review was prospectively registered at Open Science Framework Registries (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/DN93K) on 10 March 2023 and was reported following the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.11

Literature search and selectionA systematic literature search was conducted from database inception until 30 July 2023 from bibliographic databases PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. After several rounds of iterations with different keyword combinations examining the performance of the search terms included, the search strategy was finalised to generate the most comprehensive list of potentially relevant citations (Appendix S1). The keywords were constructed with a high probability of them appearing in relevant papers in bibliographic databases. Grey literature sources such as the website of the Global Research Council were also used to gather recommendation documents which applied to human RCTs. Reference lists of the selected articles were also screened for potentially relevant papers. Our inclusion criteria captured publicly available recommendation documents concerning research integrity, with no language or time restrictions, and with application to human RCTs. Our exclusion criteria were recommendation documents not applicable to human RCTs, those that gave operational guidance providing compliance standards for research governance or those that were not presented in a formal published format, for example, the Amsterdam Agenda which only existed as a short webpage (https://www.wcrif.org/guidance/amsterdam-agenda) was excluded. Thus, recommendation documents which were not accompanied by a published file in .pdf format with a digital object identifier (whether peer-reviewed or not) and those substantial html files not on an authentic website were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesisData extraction was conducted by utilising adapted versions of AGREE II,10 RIGHT11 and ACCORD12 to appraise the quality and reporting of the selected integrity recommendation documents by two reviewers (FAB and BJ) to reduce the risk of bias. Tables 1 and 2 are also appraised by two reviewers (FAB and BJ).

Recommendation documents included in the systematic review of the quality of research integrity recommendations.

| No. | Document title | Institution/author | Year of publication | Type/source of evidence | Scope | Type of consensus | Updated | Focus area, science/biomed/clinical | Number of statements | Evidence of synthesis yes/no |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Singapore statement on research integrity.15 | World Conference on Research Integrity | July 21–24, 2010 | WCRI conference | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Not mentioned | 14 | No |

| 2 | The Hong Kong Principles for assessing researchers: Fostering research integrity.16 | World Conference on Research Integrity | July 16, 2020, | WCRI conference | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 5 | No |

| 3 | The Bonn PRINTEGER statement.17 | European PRINTEGER project | February 20, 2018 | Consensus panel | Institutional Integrity | Two round Delphi | No | Science | 13 | No |

| 4 | International Multi-stakeholder Consensus Statement on Clinical Trial Integrity.3 | Cairo Consensus Group on Research Integrity | March 3, 2023 | Umbrella review | Clinical Trial Integrity | Two round Delphi | No | Clinical | 81 | Yes |

| 5 | Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity training using a modified Delphi approach.18 | University of Split School of Medicine, Croatia | September 28, 2022, | Structured questionnaire and scoping review | Research Integrity | Three round Delphi | No | Science | 62 | Yes |

| 6 | Integrity in research collaborations: the Montreal Statement.19 | World Conference on Research Integrity | May 5–8, 2013 | WCRI conference | Research Integrity of Collaborative Research | No consensus | No | Science | 20 | No |

| 7 | Statement of Principles and Practices for Research Ethics, Integrity, and Culture in the Context of Rapid-Results Research.20 | Global Research Council | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 8 | No |

| 8 | Research Integrity Practices in Science Europe Member Organisations.21 | Science Europe | July, 2016 | Survey | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 18 | No |

| 9 | CSIC National Statement on Scientific Integrity.22 | Spanish Universities | December 2, 2015 | Not mentioned | Scientific Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 15 | No |

| 10 | A consensus statement on research misconduct in the UK.23 | British Medical Journal | February 16, 2012 | High-level meeting | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 6 | No |

| 11 | The Cape Town statement on fairness, equity and diversity in research.24 | World Conference on Research Integrity | March 30, 2023 | WCRI conference | Fairness and equity | No consensus | No | Science | 20 | No |

| 12 | The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity.25 | All European Academies | 2017 | Not mentioned | Research Integrity | No consensus | Yes | Science | 64 | No |

| 13 | Framework to Enhance Research Integrity in Research Collaborations.26 | Research Integrity National Forum | 2022 | Not mentioned | Research Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 39 | No |

| 14 | Best Practices for Ensuring Scientific Integrity and Preventing Misconduct.27 | OECD Global Science Forum | Not mentioned | Tokyo workshop | Scientific Integrity | No consensus | No | Science | 52 | No |

Recommendation documents concerning research integrity and their contribution towards fostering integrity in randomised clinical trials.

| Quality score (%) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Singapore statement on research integrity.15 | AGREE II=4% | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=21% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | The Hong Kong Principles for assessing researchers: Fostering research integrity.16 | AGREE II=19% | x | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| RIGHT=57% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=10% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | The Bonn PRINTEGER statement.17 | AGREE II=18% | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=47% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=17% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | International Multi-stakeholder consensus statement on clinical trial integrity.3 | AGREE II=70% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| RIGHT=96% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=88% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity training using a modified Delphi approach.18 | AGREE II=51% | X | |||||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=71% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=77% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Integrity in research collaborations: the Montreal Statement.19 | AGREE II=8% | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=29% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=3% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Statement of principles and practices for research ethics, integrity, and culture in the context of rapid-results research.20 | AGREE II=13% | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=35% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Research integrity practices in Science Europe member organisations.21 | AGREE II=23% | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=29% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=25% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | CSIC national statement on scientific integrity.22 | AGREE II=15% | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| RIGHT=38% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | A consensus statement on research misconduct in the UK.23 | AGREE II=10% | X | X | ||||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=28% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | The Cape Town statement on fairness, equity and diversity in research.24 | AGREE II=23% | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=44% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=13% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | The European code of conduct for research integrity.25 | AGREE II=20% | X | x | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| RIGHT=44% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=10% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Framework to enhance research integrity in research collaborations.26 | AGREE II=15% | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=35% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Best practices for ensuring scientific integrity and preventing misconduct.27 | AGREE II=24% | x | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| RIGHT=49% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ACCORD=7% | ||||||||||||||||||||||

1. Generally applicable towards RCTs (meets the selection criteria for systematic review), 2. Funding disclosure, 3. Patient and public involvement, 4. Outcomes definition, 5. Sample size estimation, 6. Ethics assessment, 7. Prospective registration, 8. Governance approval, 9. Informed consent, 10. Recruitment process, 11. Data collection, 12. Monitoring and audit, 13. Pre-specified statistical analysis, 14. Authorship contribution, 15. Declaration of conflict of interests, 16. Data sharing, 17. Editorial and peer review, 18. Post-publication appraisal, 19. Evidence synthesis, 20. Future research.

At the time of this review, no tools to evaluate the quality or reporting of recommendation documents were available and ACCORD12 (Accurate Consensus Reporting Document) was only a project under development. AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation)10 checklist assesses the methodological quality and clarity of clinical guidelines overall, while the RIGHT (Reporting Items for Practice Guidelines in Healthcare)11 specifically evaluates the completeness and transparency in reporting of these guidelines. In our appraisal, the original items from these checklists were adapted to evaluate the quality and reporting of recommendation documents, while retaining the original framework (Appendices S3 and S4 give comprehensive details of the adapted assessment tools). RIGHT questions were designed for a binary “yes/no” and “unclear”, whereas AGREE II gave questions which were designed to be selected if the guideline met its criteria. Adaptations in the items for the assessment of the selected documents consisted of replacing keywords such as “indicate the strength of recommendations and the certainty of the supporting evidence” with “indicate the strength of the statements and the certainty of the supporting evidence”, to accommodate the assessment of recommendation documents concerning RCT integrity rather than clinical practice guidelines (Appendices S3 and S4). However, the framework of the domains was kept unchanged from those advised in the original tool: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation applicability, editorial independence for AGREE II13 and basic information, background, evidence, recommendations, review and quality assurance, funding, declaration and management of interest, other information for RIGHT.11 On the other hand, as mentioned, at the time of developing this manuscript, ACCORD13 (Accurate Consensus Reporting Document) was a project under development which will follow the EQUATOR Network to guide the development of reporting guidelines.12 Our ACCORD checklist is taken from Table 2 of the systematic review to inform ACCORD guideline development,13 which are the results of the systematic review. As this checklist is designed for consensus-based documents, no modifications were required. Similarly, to RIGHT,11 ACCORD13 questions were designed for a binary “yes/no” and “unclear”.

Documents assessed by both adapted RIGHT11 and ACCORD13 were graded under the categories, where “yes” awarded 1 point, “no” awarded 0 points and “unclear” awarded 0.5 points. Documents assessed by adapted AGREE were graded by awarding 1 point for each of the criteria the document had passed an agreement on, as the options for selection were not in binary form but rather just selection of the most suitable criteria. Domain scores were calculated by summing up all the scores of the individual items in the domain and by scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain. The percentage of agreed versus disagreed answers was then used as the basis for evaluation to keep the results coherent and comparable with both RIGHT and ACCORD. Data were synthesised as % of the maximum score per tool with the criteria for assessment: ≥70% good, 50–69% average and <50% poor. These cut-off values were selected as they are coherent with cut-off points in previous reviews for a 3-point system like ours i.e. “good quality”, “average quality” and “poor quality”.14

The recommendation document's contribution to promoting the integrity of RCT was assessed by evaluating its coverage across the various aspects of the entire RCT lifecycle. The following aspects were covered: general (meeting our inclusion criteria), funding, patient and public involvement, outcomes definition, sample size estimation, ethics assessment, prospective registration, governance approval, informed consent, recruitment process, data collection, monitoring and audit, pre-specified statistical analysis, authorship contribution, declaration of conflict of interests, data sharing, editorial and peer review, post-publication appraisal, evidence synthesis and future research.

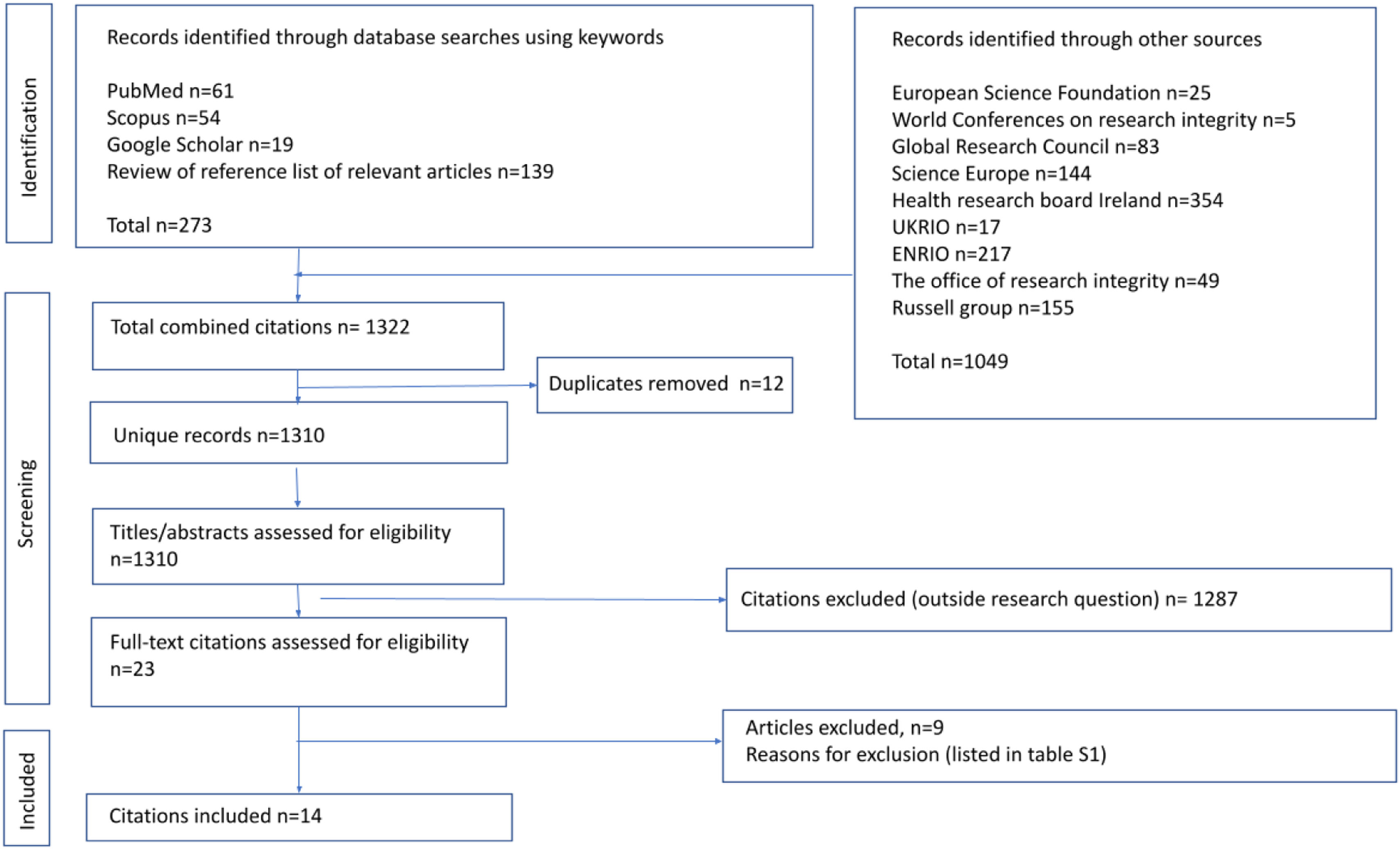

ResultsSelected literatureA total of 1322 records were identified for screening where 23 papers were selected for eligibility assessment through examination of the full text. A total of 14 recommendation documents were selected for systematic review (6 from bibliographic sources and 8 from relevant websites). Fig. 1 shows the flowchart of records obtained, screened, assessed for eligibility, and documents included in our review.

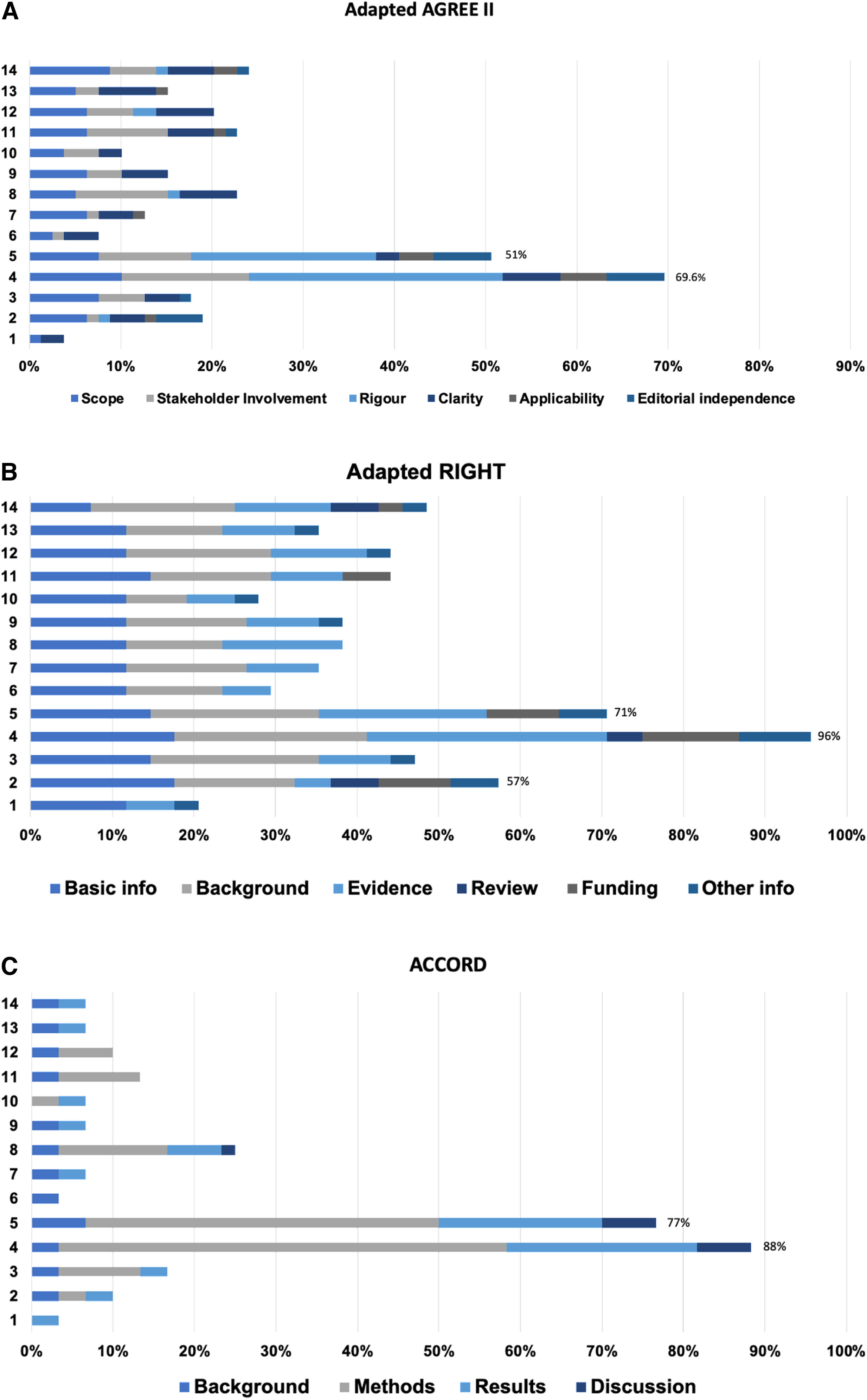

Quality appraisal of integrity recommendation documentsFig. 2A illustrates the quality of the 14 recommendation documents appraised by the adapted AGREE II checklist. The maximum achievable score was 79 quality points where documents were awarded points under 6 main categories. The “International Multi-stakeholder Consensus Statement on Clinical TrialIntegrity”3 document (#4) scored the highest quality score at 70% which put it under the category of a good-quality recommendation document. The document scored 8 points for the scope, 11 for stakeholder involvement, 22 for rigour, 5 for clarity, 4 for applicability and 5 for editorial independence, awarding it a total of 55 quality points. The “Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity using a modifiedDelphi”18 approach document (#5) scored a quality score of 51% putting it under the category of an average quality recommendation document. The document scored 6 points for scope, 8 for stakeholder involvement, 16 for rigour, 2 for clarity, 3 for applicability and 5 for editorial independence, awarding it 40 quality points. The remaining 12 documents did not reach the minimum 50% quality threshold and were put under poor quality documents.

The overall quality of the 14 research integrity recommendation documents was appraised by three adapted checklists. (A) Adapted AGREE II, (B) Adapted RIGHT and (C) ACCORD (see the methods section for details; the numbered documents correspond to the sources listed in Table 1).

Fig. 2B illustrates the quality of the 14 recommendation documents appraised by the adapted RIGHT checklist. The maximum achievable score was 34 quality points where documents were awarded points under 6 categories. Similarly, the “International multi-stakeholder consensus statement on clinical trialintegrity”3 (#4) scored the highest quality score at 96% which put it under the category of a good-quality recommendation document. The document scored 6 points for basic information, 8 points for the background, 10 points for evidence, 1.5 points for review, 4 points for funding and 3 points for other information, awarding the document 32.5 quality points in total. The “Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity using a modified Delphi approachdocument”18 (#5) scored a quality score of 71%. It scored 5 points in basic information, 7 points in background, 7 points in evidence, 0 points in review, 3 points in funding and 2 points in other information, categorising it as a good quality document. The “Hong Kong principles for assessing researchers: fostering researchintegrity”16 document (#2) scored 57% categorising it as an average-quality document. The document scored 6 in basic information, 5 in the background, 1.5 in evidence, 2 in review, 3 in funding and 2 in other information awarding it a total of 19.5 quality points. The remaining 11 documents did not reach the minimum 50% quality threshold and were categorised as poor-quality documents.

Fig. 2C illustrates the quality of the 14 recommendation documents appraised by the adapted version of ACCORD checklist. The maximum achievable score for this checklist was 30 quality points. Similarly, the “International Multi-stakeholder Consensus Statement on Clinical TrialIntegrity”3 (#4) scored the highest quality score of 88% which put it under the category of a good-quality recommendation document. The document gained 1 point in the background, 16.5 in the methods, 7 in the results and 2 in the discussion awarding it a total of 26.5 points. The “Development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity training using a modified Delphiapproach”18 (#5) document scored 77%, scoring 2 points for the background, 13 points for methods, 6 points for results and 2 points for discussion, with a total of 23 quality points. The remaining 12 documents did not reach the minimum 50% quality threshold and were labelled as poor-quality recommendation documents. The reviewer agreement fluctuated from 100 to 96% for AGREE II, 100 to 86% for RIGHT and 100 to 94% for ACCORD, the agreement regarding the quality category of each document was the same for all 14 documents (See S5 for details).

Contribution of integrity recommendation documents towards fostering RCT integrityTable 2 illustrates the included integrity documents’ individual contributions towards the RCT lifecycle covered by these recommendation documents. Under our selection criteria, all of the documents were applicable to the clinical research RCT subfield. The majority, 13 (93%) of the recommendation documents offered some specific guidance towards fostering RCT integrity. “The international multi-stakeholder consensus statement on clinical trialintegrity”3 covered all of the RCT integrity dimensions. “The development of consensus on essential virtues for ethics and research integrity training using a modifiedDelphi”18 was, in contrast to other documents, only generally applicable as it just met our inclusion criteria. It scored as a good-quality document on RIGHT and ACCORD and as an average-quality document of AGREE II. The most commonly covered guidance was on funding disclosure (11 documents, 79%), authorship and contribution (8, 57%), declaration of conflicts of interest (5, 36%), data sharing (9, 64%) and editorial and peer review (5, 36%).

DiscussionMain findingsThe overall quality and reporting of most research integrity recommendation documents were low, with critical areas such as patient and public involvement, outcomes definition, sample size estimation being some of the weakest points. Only one document achieved a high-quality score on the adapted AGREE II checklist,3 two documents on the adapted RIGHT checklist3,18 and a further two documents on the adapted ACCORD.3,18 Thirteen recommendation documents (93%) offered some specific guidance towards fostering RCT integrity, as mentioned the most covered guidance was on funding disclosure, authorship and contribution, declaration of conflicts of interest, data sharing and education and peer review, whereas all the documents were generally applicable to RCTs.

Strengths and limitationsTo the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to identify and evaluate the quality of recommendation documents concerning research integrity. One of this review's main strengths was its extensive search strategy, which encompassed both bibliographic databases and grey literature websites to identify the largest number of RCT integrity-related recommendation documents, without regard to language or time restrictions. The body of evidence this systematic review captured included the recommendation documents retrieved from an exhaustive search. One of the main challenges we encountered when performing the literature search and selection was identifying documents from bibliography sources. We discovered most of these recommendation documents are not in the form of research publications which can be retrieved from PubMed but are often PDF documents published on integrity websites, such as the UKRIO (United Kingdom Research Integrity Office, available at https://ukrio.org/). This identification made a clear path for the subsequent systematic review with which we captured 14 recommendation documents applicable to RCTs. There remains a risk that some recommendations which were not presented in a published format in journals or well-known respected websites may have been missed. This a possible limitation of our work.

Another challenge was to adapt the existing AGREE II10 and RIGHT11 checklists to appraise the quality of recommendation documents. Both AGREE II and RIGHT are checklists used to evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines, as to the best of our knowledge, no current checklists exist to evaluate such documents. AGREE II and RIGHT follow the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) network approach.28 ACCORD13 (Accurate Consensus Reporting Document) is a project currently under development which will follow the EQUATOR Network guidance for the development of reporting guidelines.28 The guideline will provide a set of items that should be reported to help the biomedical research and clinical practice describe the methods used to reach consensus in a “complete, transparent, and consistent manner”.12 We used Table 2 from the ACCORD systematic review which guides reporting items by reviewing studies that provide guidance.13

AGREE II and RIGHT are clinical practice guideline checklists, adapted in our review to appraise the quality of recommendation documents. The quality score between adapted AGREE II and RIGHT varied with each document, with the greatest difference being the Hong Kong principles16 with a quality score of 19% from AGREE II and 57% from RIGHT. This is due to the nature of the checklists, AGREE's appraisal technique is very thorough with 6 domains, each containing multiple sub-domains with no option of an “unclear” answer. RIGHT also consists of 6 domains, however, contains fewer subdomains and offers “unclear” as an option for selection. AGREE II therefore has a stricter criterion for assessment compared to RIGHT, thus all of the documents in this review scored higher on RIGHT compared to AGREE II.

According to a systematic review which outlined cut-off points for current guidelines appraisals performed with AGREE II.14 They showed that cut-off points in previous reviews for a 3-point system like ours i.e. “good quality”, “average quality” and “poor quality” were between 60% and 83%, this is because the category “medium quality guideline” was also considered. Subsequently, our data was synthesised as % of the maximum score per tool with the criteria for assessment: ≥70% good, 50–69% average and <50% poor.

Implementation and future researchThe main findings showed that all the recommendation documents included in this review could be applicable towards fostering RCT in some way. However, there is still a need to develop specific guidance to improve the integrity standard required in RCTs. Currently, evidence synthesis based on RCTs gives rise to the most robust policy recommendations and practice guidelines. Patients should be the priority in RCTs as research should be for the benefit of society. Many studies do not include patient, carer and public involvement in the design, conduct, or interpretation.29 Therefore, a more robust consumer engagement framework needs to be developed to improve the usefulness of RCTs. Recognition of this aspect will reinforce the commitment to advocating for greater inclusivity and collaboration in RCTs. Future research is also required on the development of instruments for the assessment of RCTs integrity by systematic reviews, guideline writers, journal editors and peer-reviewers.30,31 Integrity assessment is likely to be a laborious task and artificial intelligence tools once develop can assist in this evaluation minimising the risk of human errors.32

We look forward to the publication of the ACCORD checklist,13 as it will be, from the best of our knowledge the first checklist specifically to appraise the quality of consensus-based documents. This review illustrated the strengths of the ACCORD checklist, as it accurately appraised the quality of our recommendation documents, without the need for adaptations. Other recommendation documents not included in this review address issues surrounding cooperation and liaison between institutions such as universities and journals, regarding the possible and actual issues with the integrity of reported research arising before and after publication.33 This is a procedure document whereas our inclusion criteria were recommendation documents aimed at policy information.

An increasing number of organisations are developing clinical practice guidelines, however, few attempts have been made to make an explicit link between evidence and recommendations in guideline development methods. Medical and scientific evidence is commonly referenced in the discussion section however, overall not enough methodological information is provided to assure readers that the scientific information was assessed without bias and that recommendations were formulated directly by the evidence itself.34

Consensus methodology must include a systematic search and categorization of external evidence when combining it with expert knowledge. Consensus panellists usually do not do a systematic literature search prior to participating in a consensus conference for guideline development.35 This issue may introduce biases and be influenced by the panel size, composition and expertise which can lead to both inaccurate or even misleading recommendations.35 It is likely that such deficiencies are across all medicine.

Based on the findings of this review, it is now crucial to set international benchmarks for RCT integrity standards through a consensus of experts that generates recommendations to improve the integrity of RCTs. The weak points of the poor and average-quality documents can be as the groundwork to improve future development methodologies. This can then be used to produce documents which can alleviate risks to the integrity of RCTs.

ConclusionExisting recommendation documents on research integrity show low quality in reporting and development. All stakeholders in the RCT lifecycle are required to make concerted efforts to improve trust in RCT to promote evidence-based medicine. Research integrity needs to be enhanced through international consensus, with a sound and transparent methodology, including all stakeholders, to develop specific recommendations on the integrity of RCTs.

Ethical considerationsNot applicable to this type of study.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsThe roles of the authors are detailed according to the Contributor Roles Taxonomy (CRediT):

FAB: writing-original draft, investigation, data curation, project administration. KSK, AB-C, MN-N: supervision, writing-review and editing, conceptualization, methodology. BJ: data curation, validation. All authors have approved last version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI) toolsThe authors declare not having used AI tools for the development or writing of the manuscript. The ChatGPT artificial intelligence tool was used to support language editing with recommendations for improving the quality and clarity of language in this article.

K.S.K. is funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senior modality) Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Spanish Government. MN-N is granted a research fellowship by the Carlos III Research Institute (Juan Rodés JR23/00025).