In non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) with embolic risk, the guidelines recommend oral anticoagulation (OAC), although not all patients receive it. In this study, an attempt is made to identify these patients, and to study factors related to non-anticoagulation.

Material and methodsNon-interventional, cross-sectional, multicentre study was performed on a population of patients ≥18 years with a NVAF diagnosis, moderate-high embolic risk (CHADS2 score≥2), not treated with OAC. Atrial fibrillation (AF) prevalence was also collected.

ResultsAF prevalence was 4.5%, and 80.7% of the patients had NVAF (20.0% did not receive OAC). A total of 1310 non-OAC-treated patients were included (51.8% male, mean age: 76.0 years). The mean time since AF diagnosis was 58.4 months. The main therapeutic decision for stroke prevention was prescription of antiplatelet agents (82.4%, n=1078), and the main reasons were: patient refusal to monitoring (37.3%), high bleeding risk (31.1%), uncontrolled hypertension (27.9%), and frequent falls (27.6%). The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 4.6, and the HAS-BLED was 2.7 (55.9% of patients scoring HAS-BLED≥3). The most common thromboembolic risk factors were: hypertension (89.1%), age≥75 years (61.5%); the haemorrhagic factors: use of drugs increasing the bleeding risk (41.2%), uncontrolled blood pressure (33.7%).

ConclusionsAbout 20% of Spanish NVAF patients do not receive OAC in the clinical practice and are treated with antiplatelet agents, which do not reduce haemorrhagic risk. Most patients do not clearly show a contraindication to OACs, particularly considering that there are other available options (direct oral anticoagulant drugs [DOACs]).

En la fibrilación auricular no-valvular (FANV) con riesgo embólico las guías recomiendan la anticoagulación oral (ACO), aunque no todos los pacientes la reciben. En este estudio, tratamos de identificar estos pacientes y estudiar los factores relacionados con la no-anticoagulación.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional, transversal y multicéntrico. Población de estudio: pacientes ≥18 años con FANV, riesgo embólico moderado-alto (puntuación CHADS2≥2), no tratados con ACO. También se recogió la prevalencia de fibrilación auricular (FA).

ResultadosLa prevalencia de FA fue del 4,5% y del 80,7% de los pacientes presentaban FANV (20,0% no recibía ACO). Se incluyeron 1.310 pacientes no tratados con ACO (51,8% varones, edad media: 76,0 años). El tiempo medio desde el diagnóstico de FA fue de 58,4 meses. La estrategia terapéutica principal para la prevención tromboembólica fue la antiagregación (82,4%; n=1.078) y las principales razones: negativa del paciente a la monitorización (37,3%), alto riesgo de sangrado (31,1%), hipertensión no controlada (27,9%) y caídas frecuentes (27,6%). La puntuación CHA2DS2-VASc media fue 4,6 y HAS-BLED 2,7 (55,9% HAS-BLED≥3). Los factores de riesgo tromboembólico más frecuentes fueron: hipertensión (89,1%) y edad ≥75 años (61,5%); los factores de riesgo hemorrágico fueron: uso de fármacos que aumentan el riesgo de sangrado (41,2%) y presión arterial no controlada (33,7%).

ConclusionesEn la práctica clínica en España, un 20% de los pacientes con FANV no recibe ACO, y son tratados con antiagregantes, lo que no reduce el riesgo hemorrágico. La mayoría de los pacientes no presenta una clara contraindicación para ACO, más aún considerando otras opciones disponibles (anticoagulantes orales directos [ACOD]).

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia with estimated prevalence, in developed countries, of 1.5–2%, rising up to 4–5% in people over 65 years old.1 In Spain, a large population-based study found a prevalence of 4.4% in subjects older than 40 years old,2 whereas another study in primary care reported a prevalence of 6.1%.3 AF associated to high morbidity multiplies the stroke risk by 5 and the overall mortality risk by 2.4 Furthermore, cardioembolic stroke associated with AF have lower survival rates.5

Oral anticoagulation (OAC) therapy is prescribed to prevent arterial thromboembolism in AF patients and has shown to reduce the risk of stroke by about 60%.6 In non valvular AF (NVAF) patients, direct oral anticoagulant drugs (DOACs) have shown a similar or even higher rates of thromboembolic risk reduction than classical OAC7–9 and antiplatelet drugs with less bleeding risk.10 Whereas the 2012 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines only considered antiplatelet monotherapy for stroke prevention in AF patients who refused OAC or could not tolerate anticoagulants for reasons unrelated to bleeding,1,11 the 2016 ESC guidelines1,11 do not recommend antiplatelet monotherapy for stroke prevention in AF, regardless of stroke risk. Instead, 2016 ESC guidelines recommend that NVAF patients with intermediate to high embolic risk (CHADS2 score≥2 or CHA2DS2-VASc≥2) should receive antithrombotic treatment with OAC unless contraindicated, being DOACs the preferred option over Vitamin K antagonists (VKAs). NICE guidelines recommends to treat AF patients and CHA2DS2-VASC stroke risk score of ≥2 with new anticoagulants instead of aspirin.12 However, in the clinical practice there is an underuse of OAC in these patients with an elevated risk of stroke.13 In Spain, the FIATE study14 reported an utilization of 84.1% in the context of >2000 selected patients from primary care, decreasing to 40.3% in patients with non-permanent FA. In the Val-FAAP study,3 12.7% of patients with AF and CHADS2 score≥2 did not receive antithrombotic treatment and 19.3% were only treated with antiplatelet drugs.

The main objectives of the present study were: to describe demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics of the patients with NVAF and CHADS2≥2 not treated with OAC, as well as main reasons for the therapeutic decisions taken by the physicians, and prevalence of AF, NVAF and NVAF not treated with OAC in the primary care setting in Spain.

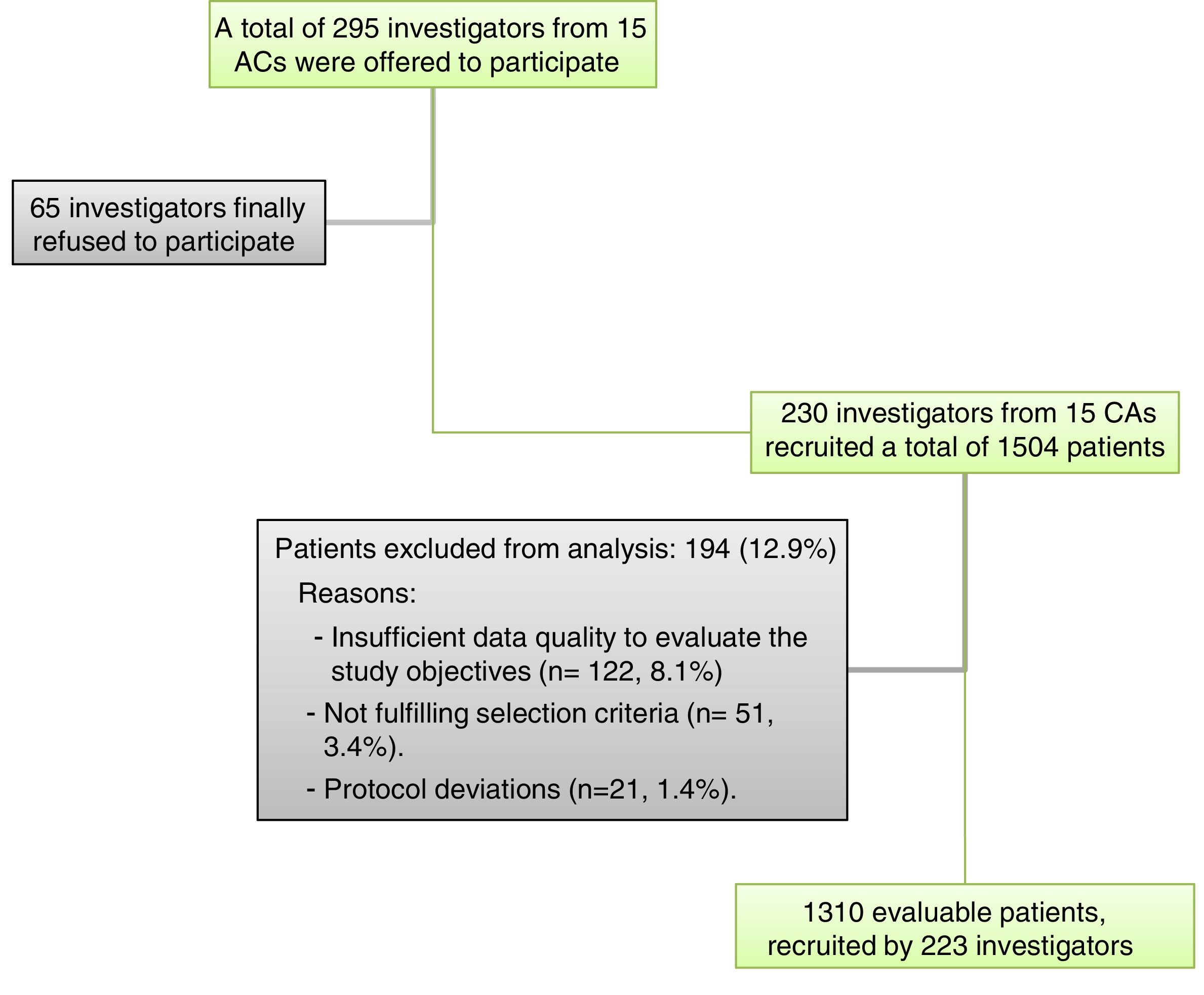

Material and methodsStudy designThis was an observational, cross-sectional, retrospective and nationwide multicentre study conducted from October 2014 to July 2015. The study population were adult patients (≥18 years) with diagnosis of NVAF (ESC Guidelines definition) documented in the clinical records, moderate to high embolic risk (defined by CHADS2 score≥2), and not treated with OAC at the time of study. The main exclusion reasons were insufficient quality of data to evaluate the study objectives (n=122, 8.1%) and not fulfilling the selection criteria (n=51, 3.4%). Other reasons were protocol deviations (n=21, 1.4%). Pregnant and breastfeeding women were also excluded. All study participants provided informed written consent prior to study enrolment.

Sample size calculationAccording to the protocol, approximately 300 primary care physicians (PCPs) had to recruit approximately 3000 patients to provide a precision of 0.0185 (with 95% confidence) in the estimation of population proportions, assuming the worst-case (maximum indetermination, p=q=0.5) and a 5% of losses due to non-evaluable patients. Finally, 1504 patients were included in the study by 230 physicians. This sample size provided a precision of 0.0283 in the estimation of population proportions (assuming the worst-case scenario and a 20 of losses), which was considered enough to achieve the objectives of the study.

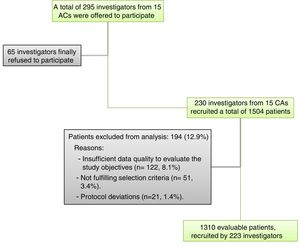

Selection of patients and researchersA total of 295 PCPs across Spain (proportionally distributed according to the relative population of their Autonomous Community) were offered to participate, from whom 230 (78.0%) participated including patients and collecting data (from 15 of the 17 Spanish Autonomous Communities) (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysisSociodemographic, AF clinical history and pharmacological treatment data were collected from medical records. The thromboembolic risk was assessed by the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores, and the bleeding risk by the HAS-BLED scale.15–17 The reasons for the decision on the therapeutic management for stroke prevention were also collected. Cognitive impairment/dementia was assessed by both the investigator's assessment (IAQ) answering a dichotomic general question (Has this patient dementia? yes or no), and the classification according the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS).18 The GDS scale has 7 stages and the overall score ranges from 7 (worse) to 1 (no dementia). Disability or dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) was assessed by the Barthel Index.19 The Barthel Index has 10 items and the overall score ranges from 0 (worse) to 100 (no dependence). Scores were classified as: 100, no dependence, 91–99, mild dependency, 61–90, moderate dependence, 21–60, severe dependence, and 0–20, total dependence.

In addition, each PCP participating provided summary information regarding the population covered by each family practice and healthcare centre, and the total number of prevalent patients with AF, NVAF and among them those NVAF with high thromboembolic risk (CHADS2≥2) not treated with OAC (overall, by gender and age category) attended by the centre.

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee at the University Hospital Ramón y Cajal (Madrid, Spain).

Statistical analysisFor the descriptive analysis, quantitative variables were described with measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean, standard deviation, median and range) and qualitative variables were described as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies. Differences between patients with and without antiplatelet agents in categorical variables were analyzed by the Chi-square test, the Fisher exact test, or likelihood-ratio test, as appropriate, and, in quantitative variables, using the t-test or the Mann–Whitney test.

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS® statistical package for Windows (version 19.0, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp).

ResultsPrevalence of AF, NVAF and NVAF not-treated with OACA total of 219 PCPs reported summary data for their assigned healthcare population. The list size mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) number of adult patients (≥ 18 years) covered per each family practice was 1497.3 (1436.2–1558.3). The overall population was 287,472 persons of whom 13,710 had AF (NFAV: n=10,889). The mean prevalence of diagnosed AF, mean value of percentage of patients with AF over the total number of patients corresponding to each area/participating centre, was 4.5% (95% CI: 3.9–5.2), of whom 80.7% (78.4–83.1) had NVAF. Among patients with NVAF, 80.0% (77.9–82.2) were treated with OAC and 20.0% (17.9–22.2) were untreated.

NVAF patients treated with OAC were characterized by a slightly higher percentage of males than females (52.2% (50.3–54.1) vs. 47.8% (45.9–49.7), respectively). According to age, most of them were subjects aged 64 or older (36.9% [34.4–39.3] and 47.4% [44.3–50.43] from 64 to 74 years and >74 years, respectively); 14.6% (12.6–16.5) aged 40–64, and 1.2% (0.7–1.7) <40 years.

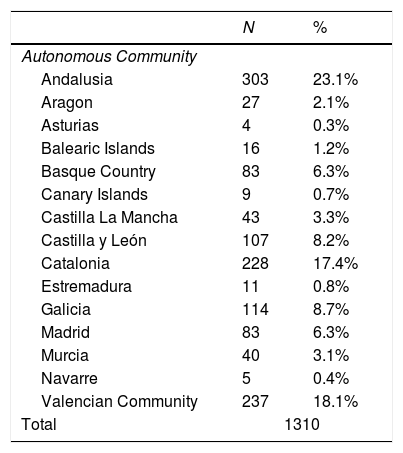

Characteristics of NVAF patients with CHADS2 score≥2 not treated with OACA total of 1504 NVAF patients with CHADS2 score≥2 not treated with OAC were included, of whom 1310 (87.1%) were considered evaluable for the analysis (see Fig. 1). The main exclusion reasons were insufficient quality of data to evaluate the study objectives (n=122, 8.1%) and not fulfilling the selection criteria (n=51, 3.4%). The distribution of the sample according to Autonomous Community of origin was approximately proportional to the relative contribution of the community to the overall Spanish population (Table 1).

Distribution of evaluable patients according to Autonomous Community of origin.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Community | ||

| Andalusia | 303 | 23.1% |

| Aragon | 27 | 2.1% |

| Asturias | 4 | 0.3% |

| Balearic Islands | 16 | 1.2% |

| Basque Country | 83 | 6.3% |

| Canary Islands | 9 | 0.7% |

| Castilla La Mancha | 43 | 3.3% |

| Castilla y León | 107 | 8.2% |

| Catalonia | 228 | 17.4% |

| Estremadura | 11 | 0.8% |

| Galicia | 114 | 8.7% |

| Madrid | 83 | 6.3% |

| Murcia | 40 | 3.1% |

| Navarre | 5 | 0.4% |

| Valencian Community | 237 | 18.1% |

| Total | 1310 | |

The therapeutic decision for stroke prevention among these patients was the prescription of antiplatelet therapy in 1078 cases (82.4%) and no OAC nor antiplatelet agent in the remaining 231 (17.6%).

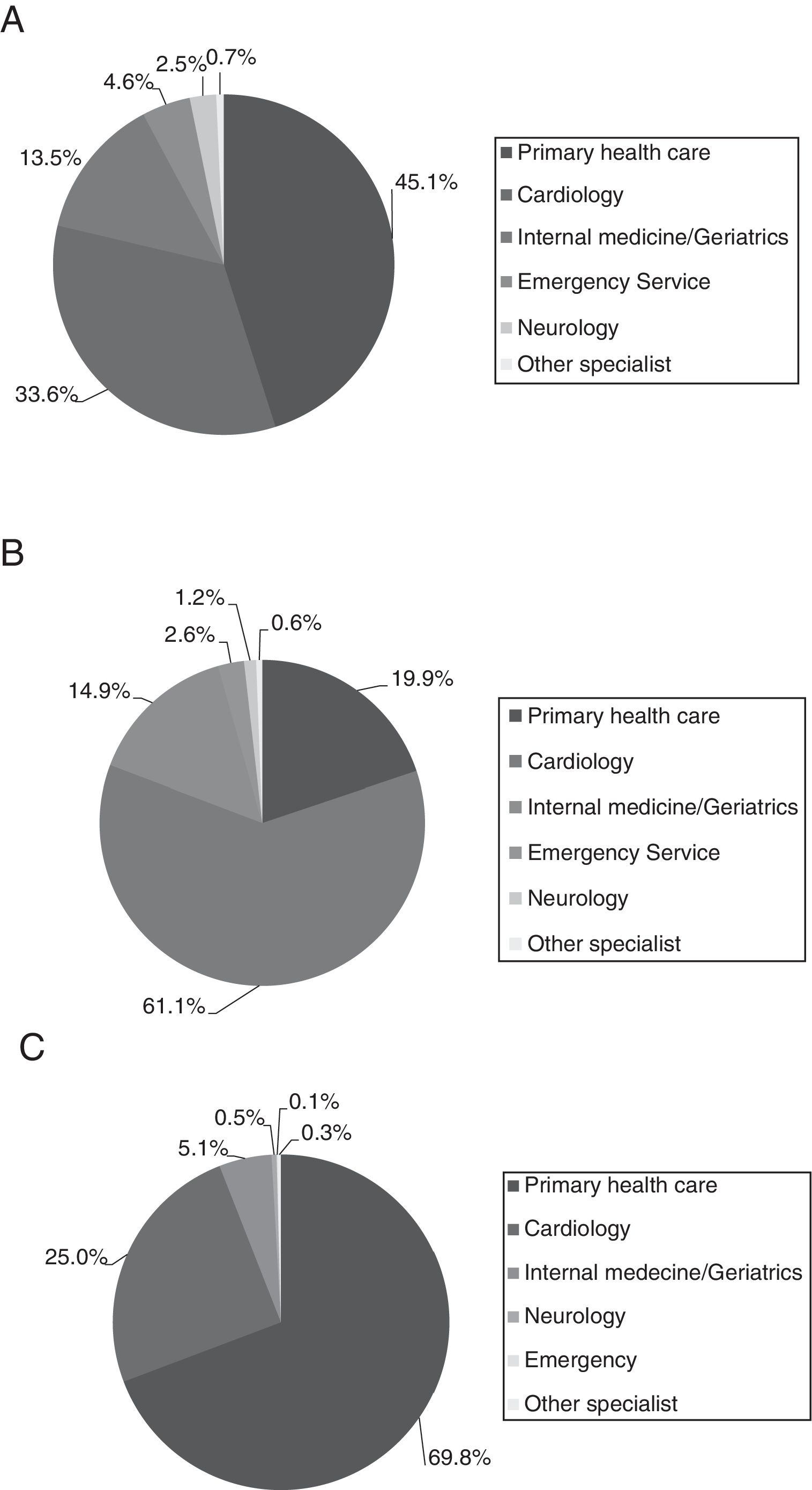

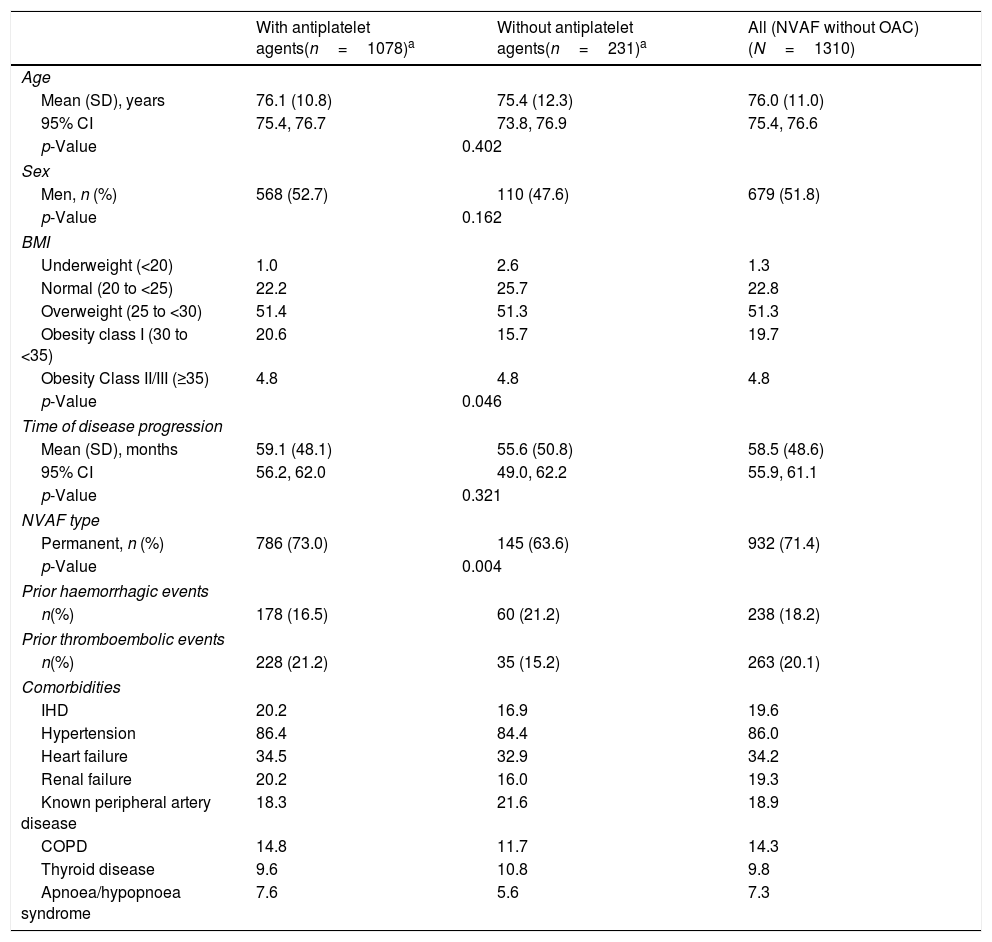

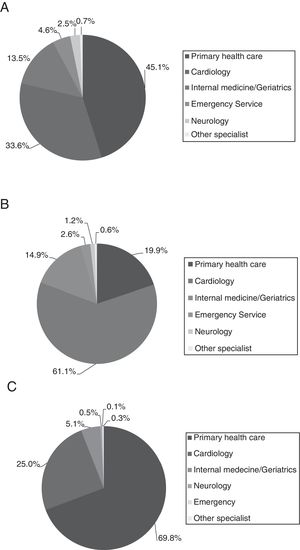

Table 2 lists the main demographic and clinical characteristics of the study sample, overall and by treatment for stroke prevention. Briefly, males accounted for 51.8% of the population and the mean age was 76.0±11.0 years. The mean (SD) time since AF diagnosis was 58.4 (48.6) months and almost three quarters (71.4%) of patients had permanent NVAF. Main patient's comorbidities were hypertension (86.0%), heart failure (34.2%) and ischaemic heart disease (19.6%). The diagnosis was done, basically, at primary care (46.5%) and cardiology specialist (33.0%) settings, as well as these two medical specialities were the ones that also indicated NVAF treatment. The medical follow-up was performed, mainly, by PCPs (70.5%) (Fig. 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics in the overall study population (NVAF not treated with OAC) and in the subgroups defined by the use of antiplatelet agents at NVAF diagnosis.

| With antiplatelet agents(n=1078)a | Without antiplatelet agents(n=231)a | All (NVAF without OAC)(N=1310) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD), years | 76.1 (10.8) | 75.4 (12.3) | 76.0 (11.0) |

| 95% CI | 75.4, 76.7 | 73.8, 76.9 | 75.4, 76.6 |

| p-Value | 0.402 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men, n (%) | 568 (52.7) | 110 (47.6) | 679 (51.8) |

| p-Value | 0.162 | ||

| BMI | |||

| Underweight (<20) | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.3 |

| Normal (20 to <25) | 22.2 | 25.7 | 22.8 |

| Overweight (25 to <30) | 51.4 | 51.3 | 51.3 |

| Obesity class I (30 to <35) | 20.6 | 15.7 | 19.7 |

| Obesity Class II/III (≥35) | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| p-Value | 0.046 | ||

| Time of disease progression | |||

| Mean (SD), months | 59.1 (48.1) | 55.6 (50.8) | 58.5 (48.6) |

| 95% CI | 56.2, 62.0 | 49.0, 62.2 | 55.9, 61.1 |

| p-Value | 0.321 | ||

| NVAF type | |||

| Permanent, n (%) | 786 (73.0) | 145 (63.6) | 932 (71.4) |

| p-Value | 0.004 | ||

| Prior haemorrhagic events | |||

| n(%) | 178 (16.5) | 60 (21.2) | 238 (18.2) |

| Prior thromboembolic events | |||

| n(%) | 228 (21.2) | 35 (15.2) | 263 (20.1) |

| Comorbidities | |||

| IHD | 20.2 | 16.9 | 19.6 |

| Hypertension | 86.4 | 84.4 | 86.0 |

| Heart failure | 34.5 | 32.9 | 34.2 |

| Renal failure | 20.2 | 16.0 | 19.3 |

| Known peripheral artery disease | 18.3 | 21.6 | 18.9 |

| COPD | 14.8 | 11.7 | 14.3 |

| Thyroid disease | 9.6 | 10.8 | 9.8 |

| Apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome | 7.6 | 5.6 | 7.3 |

Data are percentages except when otherwise indicated.

The initial decision of management was unknown in 1 patient in the analysis by subpopulations. BMI=Body Mass Index; CI=confidence interval; COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IHD=ischaemic heart disease; NVAF=non-valvular atrial fibrillation; OAC=oral anticoagulation; SD=standard deviation.

The 25.7% of patients were identified as demented. When applying the GDS scale, 28.0% of patients scored≤2, 55.6% scored 3–5, and 16.4% scored≥6. The mean (SD) Barthel Index, was of 80.9 (27.7) points, indicating a low/moderate level of dependence, but 21.4% of the patients had ≤60 points in the Barthel Index (severe/total dependence).

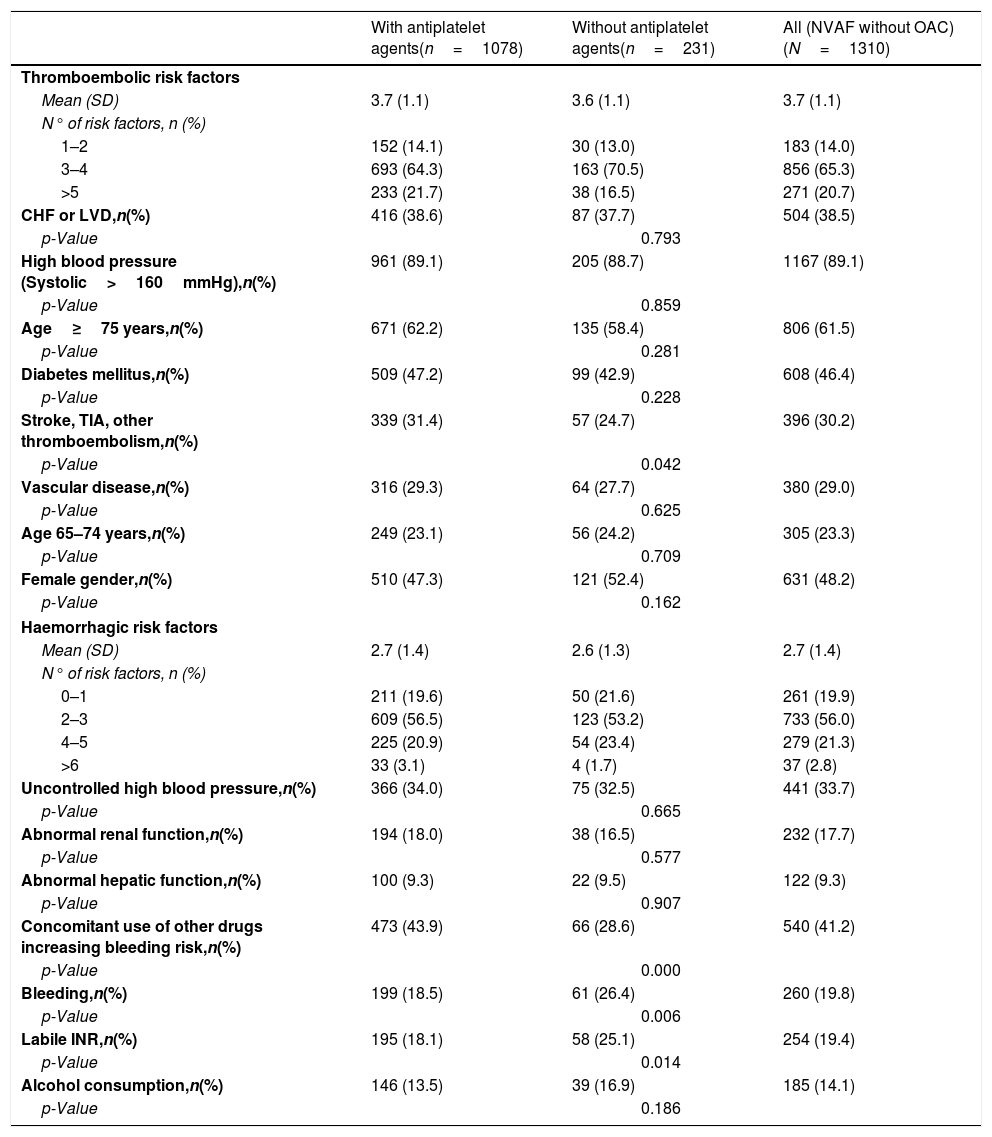

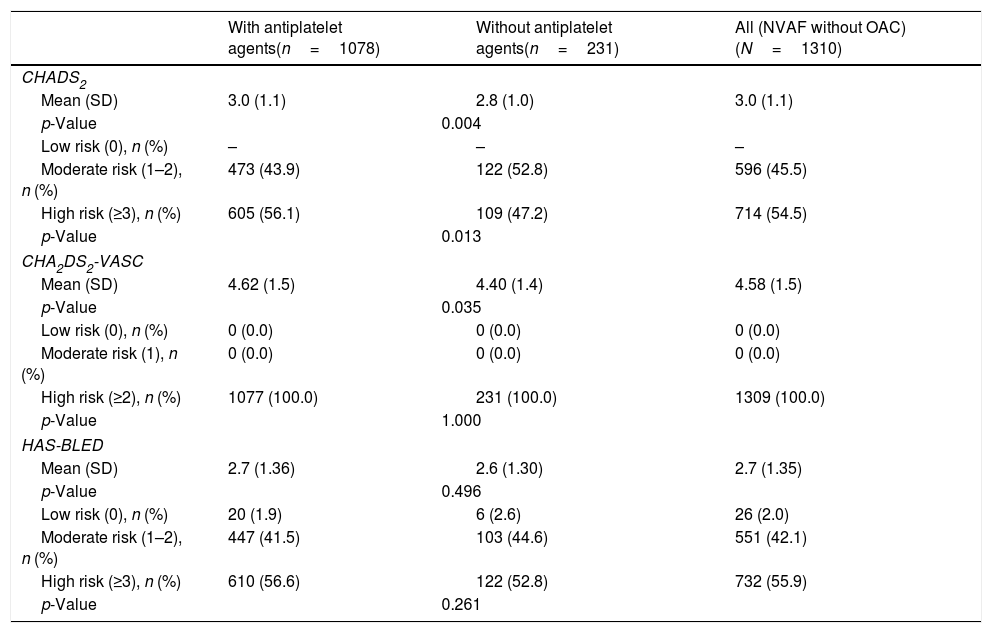

The thromboembolic risk was high in 54.5% of the patients and in 100.0% of the patients according CHADS2 (mean [95% CI]: 3.0 [2.9–3.0]) and CHA2DS2-VASc (mean [95% CI]: 4.6 [4.5–4.7]) scales, respectively. The mean (SD) number of thromboembolic factors was 3.7 (1.1). The 65.3% of patients had from 3 to 4 thromboembolic risk factors being the most common: hypertension (89.1%), age≥75 years (61.5%), female gender (48.2%), and diabetes mellitus (46.4%) (Table 3).

Haemorrhagic and thromboembolic risk factors in the overall study population and in the subgroups defined by the use of antiplatelet agents at NVAF diagnosis.

| With antiplatelet agents(n=1078) | Without antiplatelet agents(n=231) | All (NVAF without OAC)(N=1310) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thromboembolic risk factors | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.7 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.1) |

| N° of risk factors, n (%) | |||

| 1–2 | 152 (14.1) | 30 (13.0) | 183 (14.0) |

| 3–4 | 693 (64.3) | 163 (70.5) | 856 (65.3) |

| >5 | 233 (21.7) | 38 (16.5) | 271 (20.7) |

| CHF or LVD,n(%) | 416 (38.6) | 87 (37.7) | 504 (38.5) |

| p-Value | 0.793 | ||

| High blood pressure (Systolic>160mmHg),n(%) | 961 (89.1) | 205 (88.7) | 1167 (89.1) |

| p-Value | 0.859 | ||

| Age≥75 years,n(%) | 671 (62.2) | 135 (58.4) | 806 (61.5) |

| p-Value | 0.281 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus,n(%) | 509 (47.2) | 99 (42.9) | 608 (46.4) |

| p-Value | 0.228 | ||

| Stroke, TIA, other thromboembolism,n(%) | 339 (31.4) | 57 (24.7) | 396 (30.2) |

| p-Value | 0.042 | ||

| Vascular disease,n(%) | 316 (29.3) | 64 (27.7) | 380 (29.0) |

| p-Value | 0.625 | ||

| Age 65–74 years,n(%) | 249 (23.1) | 56 (24.2) | 305 (23.3) |

| p-Value | 0.709 | ||

| Female gender,n(%) | 510 (47.3) | 121 (52.4) | 631 (48.2) |

| p-Value | 0.162 | ||

| Haemorrhagic risk factors | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.3) | 2.7 (1.4) |

| N° of risk factors, n (%) | |||

| 0–1 | 211 (19.6) | 50 (21.6) | 261 (19.9) |

| 2–3 | 609 (56.5) | 123 (53.2) | 733 (56.0) |

| 4–5 | 225 (20.9) | 54 (23.4) | 279 (21.3) |

| >6 | 33 (3.1) | 4 (1.7) | 37 (2.8) |

| Uncontrolled high blood pressure,n(%) | 366 (34.0) | 75 (32.5) | 441 (33.7) |

| p-Value | 0.665 | ||

| Abnormal renal function,n(%) | 194 (18.0) | 38 (16.5) | 232 (17.7) |

| p-Value | 0.577 | ||

| Abnormal hepatic function,n(%) | 100 (9.3) | 22 (9.5) | 122 (9.3) |

| p-Value | 0.907 | ||

| Concomitant use of other drugs increasing bleeding risk,n(%) | 473 (43.9) | 66 (28.6) | 540 (41.2) |

| p-Value | 0.000 | ||

| Bleeding,n(%) | 199 (18.5) | 61 (26.4) | 260 (19.8) |

| p-Value | 0.006 | ||

| Labile INR,n(%) | 195 (18.1) | 58 (25.1) | 254 (19.4) |

| p-Value | 0.014 | ||

| Alcohol consumption,n(%) | 146 (13.5) | 39 (16.9) | 185 (14.1) |

| p-Value | 0.186 | ||

CHF=congestive heart failure; LVD=left ventricular dysfunction; NVAF=non-valvular atrial fibrillation; OAC=oral anticoagulation; SD=standard deviation; TIA=transient ischaemic attack.

Based on the HAS-BLED scale (mean [95% CI]: 2.7 [2.6–2.8]), the bleeding risk was high in 55.9% of the patients (Table 4). The mean (SD) number of haemorrhagic factors was 2.7 (1.4). The 56.0% of patients had from 2 to 3 haemorrhagic risk factors being the most common: concomitant drug use that may increase the bleeding risk (41.2%) and uncontrolled hypertension (33.7%) (Table 3).

Haemorrhagic and thromboembolic risk scores (CHADS2, CHA2DS2-VASC and HADS) in the overall study population and in the subgroups defined by the use of antiplatelet agents at NVAF diagnosis.

| With antiplatelet agents(n=1078) | Without antiplatelet agents(n=231) | All (NVAF without OAC)(N=1310) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHADS2 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.1) | 2.8 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.1) |

| p-Value | 0.004 | ||

| Low risk (0), n (%) | – | – | – |

| Moderate risk (1–2), n (%) | 473 (43.9) | 122 (52.8) | 596 (45.5) |

| High risk (≥3), n (%) | 605 (56.1) | 109 (47.2) | 714 (54.5) |

| p-Value | 0.013 | ||

| CHA2DS2-VASC | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.62 (1.5) | 4.40 (1.4) | 4.58 (1.5) |

| p-Value | 0.035 | ||

| Low risk (0), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Moderate risk (1), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| High risk (≥2), n (%) | 1077 (100.0) | 231 (100.0) | 1309 (100.0) |

| p-Value | 1.000 | ||

| HAS-BLED | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (1.36) | 2.6 (1.30) | 2.7 (1.35) |

| p-Value | 0.496 | ||

| Low risk (0), n (%) | 20 (1.9) | 6 (2.6) | 26 (2.0) |

| Moderate risk (1–2), n (%) | 447 (41.5) | 103 (44.6) | 551 (42.1) |

| High risk (≥3), n (%) | 610 (56.6) | 122 (52.8) | 732 (55.9) |

| p-Value | 0.261 | ||

NVAF=non-valvular atrial fibrillation; OAC=oral anticoagulation.

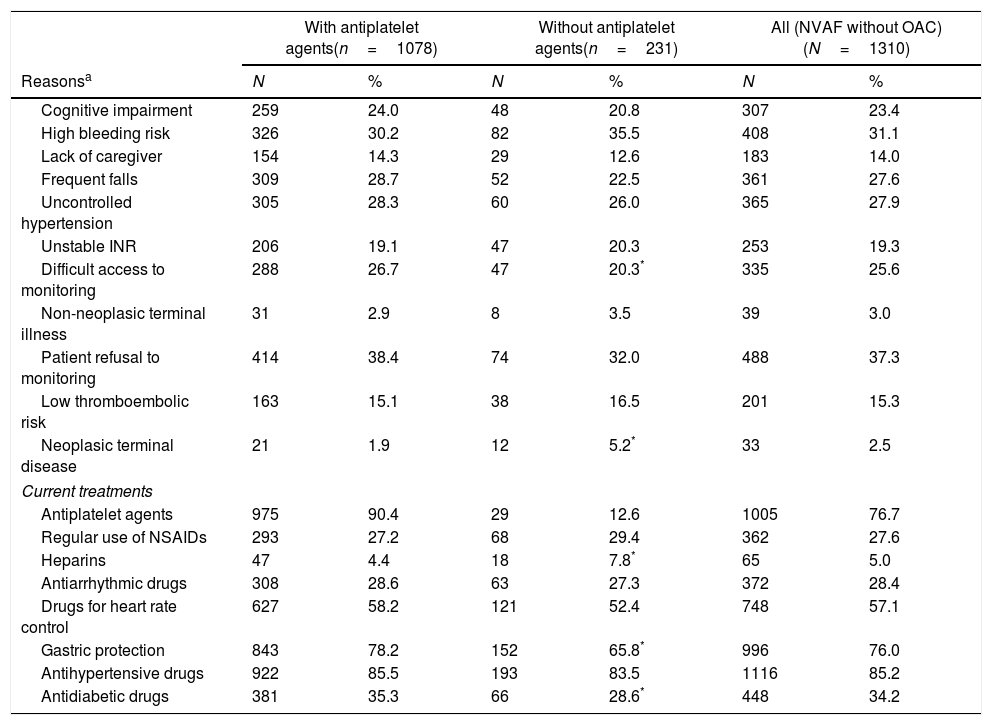

Regarding the reasons for therapeutic management decision, 89.6% of the patients had the reasons in the clinical history (10.4% [136 patients] had no reasons for the decision in the clinical history). Almost 2 out of 3 had more than one reason for the decision: 24.4% presented 2 (24.0% in group only treated with antiplatelet; 26.0% for group without antithrombotic agents), and 37.8% had 3 or more reasons (38.1% in group only treated with antiplatelet; 36.4% for group without antithrombotic agents). In patients in whom physicians decided to prescribe only antiplatelet agents at diagnosis (n=1078, 82.4%), the main reason was patient refusal to monitoring (38.4%). A high bleeding risk (30.2%), frequent falls (28.7%), uncontrolled hypertension (28.3%), difficult access to monitoring (26.7%), cognitive impairment (24.0%), and unstable INR (19.1%) were other treatment management decision reasons. Currently, 90.4% of these patients are still treated with antiplatelet agents (Table 5).

Reasons for therapeutic management decision at NVAF diagnosis and current treatments.

| With antiplatelet agents(n=1078) | Without antiplatelet agents(n=231) | All (NVAF without OAC)(N=1310) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reasonsa | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Cognitive impairment | 259 | 24.0 | 48 | 20.8 | 307 | 23.4 |

| High bleeding risk | 326 | 30.2 | 82 | 35.5 | 408 | 31.1 |

| Lack of caregiver | 154 | 14.3 | 29 | 12.6 | 183 | 14.0 |

| Frequent falls | 309 | 28.7 | 52 | 22.5 | 361 | 27.6 |

| Uncontrolled hypertension | 305 | 28.3 | 60 | 26.0 | 365 | 27.9 |

| Unstable INR | 206 | 19.1 | 47 | 20.3 | 253 | 19.3 |

| Difficult access to monitoring | 288 | 26.7 | 47 | 20.3* | 335 | 25.6 |

| Non-neoplasic terminal illness | 31 | 2.9 | 8 | 3.5 | 39 | 3.0 |

| Patient refusal to monitoring | 414 | 38.4 | 74 | 32.0 | 488 | 37.3 |

| Low thromboembolic risk | 163 | 15.1 | 38 | 16.5 | 201 | 15.3 |

| Neoplasic terminal disease | 21 | 1.9 | 12 | 5.2* | 33 | 2.5 |

| Current treatments | ||||||

| Antiplatelet agents | 975 | 90.4 | 29 | 12.6 | 1005 | 76.7 |

| Regular use of NSAIDs | 293 | 27.2 | 68 | 29.4 | 362 | 27.6 |

| Heparins | 47 | 4.4 | 18 | 7.8* | 65 | 5.0 |

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | 308 | 28.6 | 63 | 27.3 | 372 | 28.4 |

| Drugs for heart rate control | 627 | 58.2 | 121 | 52.4 | 748 | 57.1 |

| Gastric protection | 843 | 78.2 | 152 | 65.8* | 996 | 76.0 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 922 | 85.5 | 193 | 83.5 | 1116 | 85.2 |

| Antidiabetic drugs | 381 | 35.3 | 66 | 28.6* | 448 | 34.2 |

In patients in whom physicians decided not to prescribe any antithrombotic agents (n=231, 17.6%), the most common reasons were: high bleeding risk (35.5%), patient refusal to monitoring (32.0%), uncontrolled hypertension (26.0%), frequent falls (22.5%), cognitive impairment (20.8%), and unstable INR (20.3%). Currently, 12.6% of these patients have initiated treatment with antiplatelet agents (Table 5).

Besides antiplatelet drugs, most common pharmacological treatments in the study population were anti-hypertensive agents (85.2%), drugs for gastric protection (76.0%), drugs for heart rate control (57.1%), antidiabetic drugs (34.2%), antiarrhythmic drugs (28.4%) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (27.6%) (Table 5). In addition, it important to note that the majority of patients (93.4%) were treated with only one antiplatelet drug; only 4.0% and 0.1% patients were treated with 2 or ≥3 antiplatelet drugs, respectively.

Differences between patients with and without antiplatelet agents at NVAF diagnosisPatients treated with antiplatelet therapy had more history of stroke, transitory ischaemic attack or other thromboembolic events (31.4% vs. 24.7% in patients without antiplatelet agents, p=0.042) more concomitant use of other drugs that may increase the bleeding risk (43.9% vs. 28.6%, p<0.001), less history of bleeding (18.5% vs. 26.4%, p=0.006) and labile INR (18.1% vs. 25.1%, p=0.014) (Table 3). They had also showed more prior thromboembolic events (21.2% vs. 15.2%) and less haemorrhagic events (16.5% vs. 21.2%) (Table 2), and higher mean scores in the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scales (Table 4). Finally, they were receiving more gastric protection and antidiabetic drugs (78.2% vs. 65.8% [p<0.001]; 35.3% vs. 28.6% [p=0.049], respectively), whereas the heparin use was less frequent (4.4% vs. 7.8% [p=0.029]) (Table 5).

DiscussionThe present multicentre study allowed quantifying and characterizing the subset of patients with NVAF and CHADS2≥2 that did not receive OAC in the primary care Spanish clinical practice in 2014–2015. The overall estimated prevalence of AF in our study was 4.5%, similar to the 4.4% reported by the OFRECE study2 and slightly lower than the 6.1% reported in the VAL-FAAP study.3 However, the OFRECE study included general Spanish population older than 40 years and to whom an ECG was performed whereas our study included patients older than 18 years already diagnosed of AF. Approximately 2 in 10 patients with NVAF were not receiving OAC, similarly than in the FIATE study.14 Also, they seem to reflect a lower under-use of OAC in Spain compared to other European countries as Germany (39%)20 or Sweden (36%),21 and similar under-use that in United States (23%)22 despite of different patients populations included in these studies (CHA2DS2-VASc>1 for Wilke et al., AF patients without risk assessment for Andersson et al., and CHA2DS2-VASc≥2 for Hess et al.). In Italy, only 27% of acute stroke patients with known AF and without contraindications had received OAC prior to the stroke event.23 In this regard, a recent published study from ambulatory care sites in the United States22 stated that most of the patients not receiving OAC had multiple risk factors and a Class I guideline24 indication for OAC. In line, the Spanish ACTUA study concluded that a considerable number of NVAF patients in Spain who could benefit from DOACs were not treated with them.25

Different reasons have been suggested to explain this under-use of OAC in patients with AF. One of the reasons for not using ACOs was the associated haemorrhagic risk. In many cases, it has been shown to be similar to that of using antiplatelet agents. In the Spanish AFABE study,26 conducted in patients older than 60 years, the most common reasons for not administering or for discontinuing OAC in patients with AF were: cognitive impairment (15.1%), risk of haemorrhage (14.3%) and patient refusal/preference (13.6%). For instance, some studies have claimed that limitations associated to treatment with antivitamin K agents, to thromboembolic risk infraestimation, and to bleeding risk concerns, especially with elderly population with AF or NVAF could explain the underutilization of OAC.22,27,28 Moreover, there is also a reluctance to use OAC due to the need for continuous monitoring, and frequent interactions with other drugs or foods.29

According to the ESC guidelines at the time of study conduction30 all patients with AF and risk factors for stroke should receive a classical OAC or a DOACs, and only those who refused OAC or could not tolerate them were candidates to antiplatelet monotherapy. This recommendation is now abolished in current guidelines11 where aspirin is not recommended. In the analyzed cohort of 1310 NVAF patients with a CHADS2≥2, 82.4% were receiving antiplatelet agents generally perceived as a “harmless treatment”. Not negligibly, 17.6% of patients were not receiving any antithrombotic treatment. In this subgroup, the main reason for the therapeutic decision was patient refusal to monitoring, a high bleeding risk, frequent falls, uncontrolled hypertension, difficult access to monitoring, cognitive impairment, and unstable INR. These reasons were similar to those reported in the already mentioned Spanish AFABE study26 as well as in the Swedish study by Andersson et al.21 In our sample of moderate-to-high risk of stroke, physicians considered that 15% of subjects were at low thromboembolic risk.

Patient refusal to the continuous monitoring needed with the classical OAC can be arranged by the use of DOACs. The AVERROES study has shown that apixaban was clearly superior to aspirin without significantly increasing major bleeding events,31 supporting an alternative to antiplatelet for those NVAF patients not suitable for OAC treatment. It is expected that the growing evidence of favourable profile of safety and effectiveness of DOACs vs. VKA and the increasingly use in the clinical practice will enhance the use of anticoagulant therapy in patients with NVAF.32 For instance, patients with SAMe-TT2R2 score>2 have been proposed as good candidates for receiving DOACs instead of VKA.33 Nevertheless, therapeutic decisions in AF patients must be accompanied by regular reviews and efforts to correct the haemorrhagic risk factors that are reversible.1,11 In the present study, at least half of subjects had a HAS-BLED score≥3, and there was a high prevalence of modifiable bleeding risk factors, suggesting that more efforts are needed in the clinical practice for controlling the blood pressure and reduce the concomitant use of drugs increasing bleeding risk, mainly NSAIDs. For instance, our study showed that labile INR was one of the main reasons for therapeutic management decision even when this risk factor could be easily remedied with DOACs use.

Strengths of our study include an important number of participating centres geographically distributed across Spain and the consecutive inclusion of all patients who met selection criteria ensuring the representativeness of our sample. Regarding limitations, as the study was observational, it did not allow evaluating a causal relationship between thromboembolic events and treatments. Despite the high number of PCP and centres participating in the study (approximately 8 in 10 accepted to participate), we cannot discard a selection bias. However, the sociodemographic characteristics of our cohort were similar to those from previous large cohorts of NVAF patients collected in our country, thus supporting the external validity of our study.14,26 Another limitation was the inability to individually check NVAF diagnosis for each patient included in the prevalence questionnaire and, therefore, to check if the number of patients provided by physicians was exact. At last, (1) only patients with AF diagnosis registered in the medical history of primary health care were included leading to a possible underdiagnosis and underreporting of patients, as well as (2) only patients with a CHADs score≥2 were able to participate in the study, excluding patients with only one risk factor.

ConclusionsApproximately 1 in 5 patients diagnosed with NVAF and associated embolic risk in Spain do not receive OAC in the clinical practice, which are characterized by a mean age of 75 years old, with comorbidities, and a high prevalence of modifiable risk factors. Their therapeutic management is inadequate, since most of them are receiving antiplatelet agents, despite the bleeding risk associated.

These findings emphasize the need for optimize the therapeutic management of NVAF patients, according to the most recent recommendations.11

Authors’ contributionsJPG and DVO participated in the design of the study, data compilation, data analyses and interpretation, and the writing, reviewing and acceptance of the final version of the manuscript. FF, IU, SFC and JC participated in the design of the study, data analyses and interpretation, and the writing, reviewing and acceptance of the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was sponsored by Bristol-Myers-Squibb and Pfizer.

Conflict of interestJosé Chaves, Irune Unzueta and Susana Fernández de Cabo are Pfizer employees. The other authors do not have any conflict of interest.

Manuscript writing and editorial support was provided by Anaïs Estrada-Gelonch from TFS Develop and was funded by Pfizer & BMS, Madrid, Spain.