To assess the methodological and reporting quality of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) for prenatal care from high-income countries (HIC) on nutritional counselling.

MethodsFollowing registration in PROSPERO (CRD42023397756), searches in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar covered the last decade. CPGs for prenatal care from HIC with nutritional counselling, without language restriction, were selected. Data extraction and quality assessment were independently conducted in duplicate, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer. The methodological and reporting quality was evaluated in institutional CPGs and professional societies using the AGREE II tool (score range 22–161), while reporting quality was evaluated with RIGHT tool (score range 0–35).

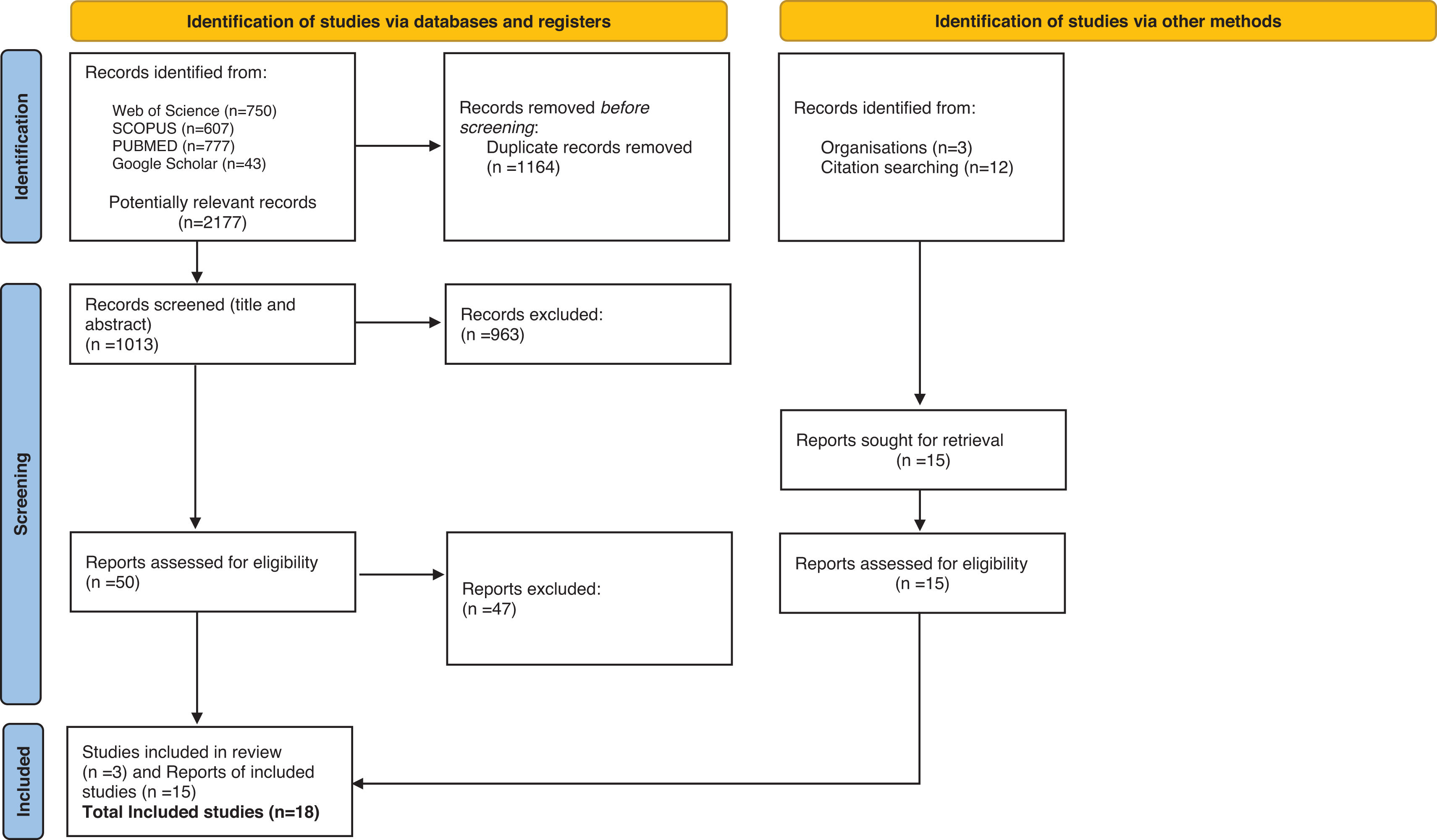

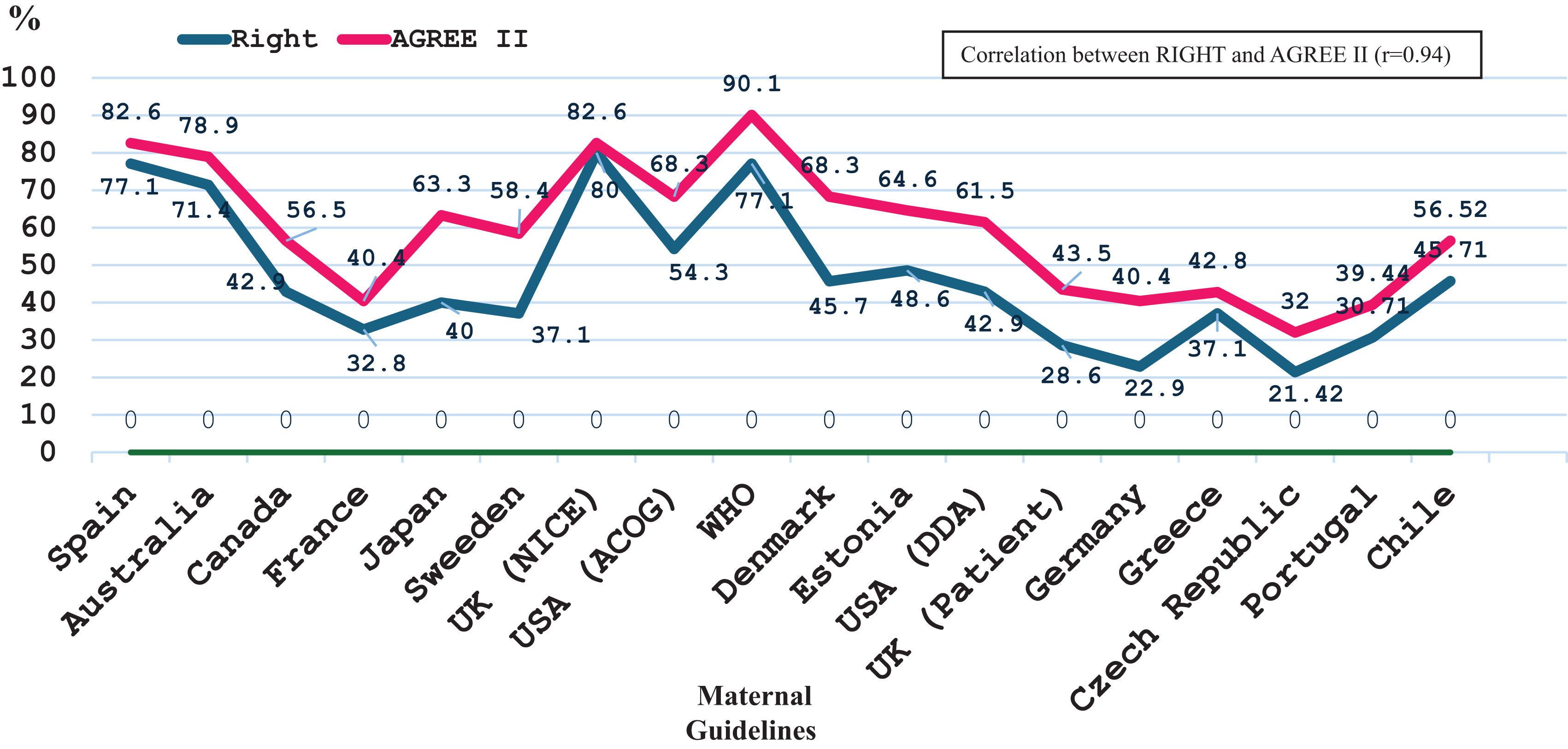

ResultsA total of 2177 citations were screened, resulting in 18 CPGs recommendations on nutritional counselling (published 2014–2024), primarily from Europe (n=11, 61.1%) and the USA (n=2, 11.1%). High-quality CPGs were 6 (33.4%) using AGREE II (Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, U.S.A.-ACOG, WHO, and Denmark) and 4 (22.2%) using RIGHT (Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, and WHO). The AGREE II and RIGHT observed score ranges were 51.5–145 and 7.5–28, respectively. Mean scores for institutional CPGs were higher than those for professional societies (AGREE 107.4±26.8 vs. 86.2±26.1, p=0.0218; RIGHT 19.1±6.2 vs. 14.1±6.1, p=0.0201). A positive correlation was observed between AGREE II and RIGHT scores (r=0.94).

ConclusionsThe methodological and reporting quality of CPGs for prenatal care with nutritional counselling from HIC varied with institutional CPGs scoring significantly better than those from professional societies. These findings underscore the need for standardized development and reporting of CPGs to ensure clear, actionable, and evidence-based nutritional advice.

Evaluar la calidad metodológica de las guías de práctica clínica (GPC) para la atención prenatal de los países de altos ingresos (en inglés, HIC) sobre el asesoramiento nutricional.

MétodosTras el registro en PROSPERO (CRD42023397756), las búsquedas en PUBMED, SCOPUS, Web of Science y Google Scholar abarcaron la última década. Se seleccionaron GPC para la atención prenatal de HIC con asesoramiento nutricional, sin restricción de idioma. La extracción de datos y la evaluación de la calidad se realizaron de forma independiente por duplicado, y las discrepancias fueron resueltas por un tercer revisor. La calidad metodológica y de los informes se evaluó en GPC institucionales y sociedades profesionales utilizando la herramienta AGREE II (rango de puntuación 22-161), mientras que la calidad de los informes se evaluó con la herramienta RIGHT (rango de puntuación 0-35).

ResultadosSe seleccionaron un total de 2.177 citas, lo que dio como resultado 18 recomendaciones de GPC sobre asesoramiento nutricional (publicadas 2014-2024), principalmente de Europa (n=11, 61,1%) y Estados Unidos (n=2, 11,1%). Las GPC de alta calidad fueron 6 (33,4%) utilizando AGREE II (España, Australia, UK-NICE, U.S.A.-ACOG, OMS y Dinamarca) y 4 (22,2%) utilizando RIGHT (España, Australia, UK-NICE y OMS). Los rangos de puntuación observados de AGREE II y RIGHT fueron 51,5-145 y 7,5-28, respectivamente. Las puntuaciones medias de las GPC institucionales fueron superiores a las de las sociedades profesionales (AGREE 107,4±26,8 vs. 86,2±26,1, p=0,0218; RIGHT 19,1±6,2 vs. 14,1±6,1, p=0,0201). Se observó una correlación positiva entre las puntuaciones AGREE II y RIGHT (r=0,94).

ConclusionesLa calidad metodológica y de notificación de las GPC para la atención prenatal con asesoramiento nutricional de HIC varió, siendo las GPC institucionales las que puntuaron significativamente mejor que las de las sociedades profesionales. Estos hallazgos subrayan la necesidad de estandarizar el desarrollo y la presentación de informes de GPC para garantizar un asesoramiento nutricional claro y basado en la evidencia.

During pregnancy, maternal lifestyle choices play an essential role in promoting the health of both the mother and the fetus.1–4 Routine prenatal care aims to promote healthy lifestyles, including adequate nutrition.5–7 Dietary advice during pregnancy provides benefits for maternal and offspring health, reducing morbidity8 and healthcare costs.1 Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), statements that provide recommendations for optimizing patient care, should be systematically developed and informed by a review of the evidence.9 However, the information within CPGs of pregnancy care is often inconsistent and sometimes contradictory, particularly when considering different countries or contexts.5,10,11 While these CPGs provide specific recommendations for screening potential problems and conditions, they are often ambiguous regarding health promotion.5 The differences and deficiencies in CPGs may be linked to their development and reporting.

In response to the need for more consistent and comprehensive guidance, the World Health Organization (WHO) released updated antenatal care recommendations in 2016, designed to promote a positive pregnancy experience.7 These CPGs explicitly recommend advising on maintaining a healthy diet, physical activity, and avoiding excessive weight gain in all contexts. However, it remains unclear to what extent these recommendations have been integrated into CPGs in high-income countries (HIC). Although CPGs focusing on weight gain and nutrition during pregnancy were evaluated for their quality using the AGREE II tool,12,13 to our knowledge, no previous works have assessed these aspects in CPGs from economically HIC using and comparing the AGREE II14 and the RIGHT tools.15 Our objective was to assess the methodological and reporting quality of CPGs from HIC that include lifestyle recommendations, with a focus on nutritional advice.

MethodsThis systematic review was prospectively registered in the international Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42023397756 (date 25 February 2023). We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement for reporting.16

Search and selectionTwo independent researchers (MMRA and MRRG) carried out the literature search using PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar from last decade. In case of disagreements and failed consensus, a third reviewer helped decide (NCI). The used keywords were: “prenatal”, “antenatal”, “gestation”, “pregnancy”, “guideline”, “guide”, “high-income countries”, and “developed countries”. The search string combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with free-text terms in the title: (prenatal OR antenatal OR gestation OR pregnancy) AND (guideline* OR guide*). The search strategies are available in Table A.1. References for included CPGs were also searched for additional CPGs eligible for inclusion. EndNote reference manager was used to retrieve, from each database, and stored, titles and abstracts of CPGs.

Predefined eligibility criteria were CPGs related to (1) pregnant women, and (2) HIC according to the World Bank.17 HIC was defined based on the gross national income per capita.18 No language restriction was applied. If multiple versions of the CPGs exist, we included the most up-to-date version, provided it did not omit any information found in earlier versions. Exclusion criteria were any document focused on low- and middle-income countries, published before last decade, and if they addressed specific interventions or pregnancies with pre-existing conditions or risk factors.

Data extraction and quality assessmentData extraction and quality assessment were independently performed by two reviewers (MMRA and MRRG). Any disagreement was resolved by consensus with a third reviewer (NCI). The following information was collected from each CPG: (1) guideline name and year of publication, (2) document type, (3) country, (4) version, (5) publication journal, (6) number of clinical visits and recommendations, and (7) nutritional health advice.

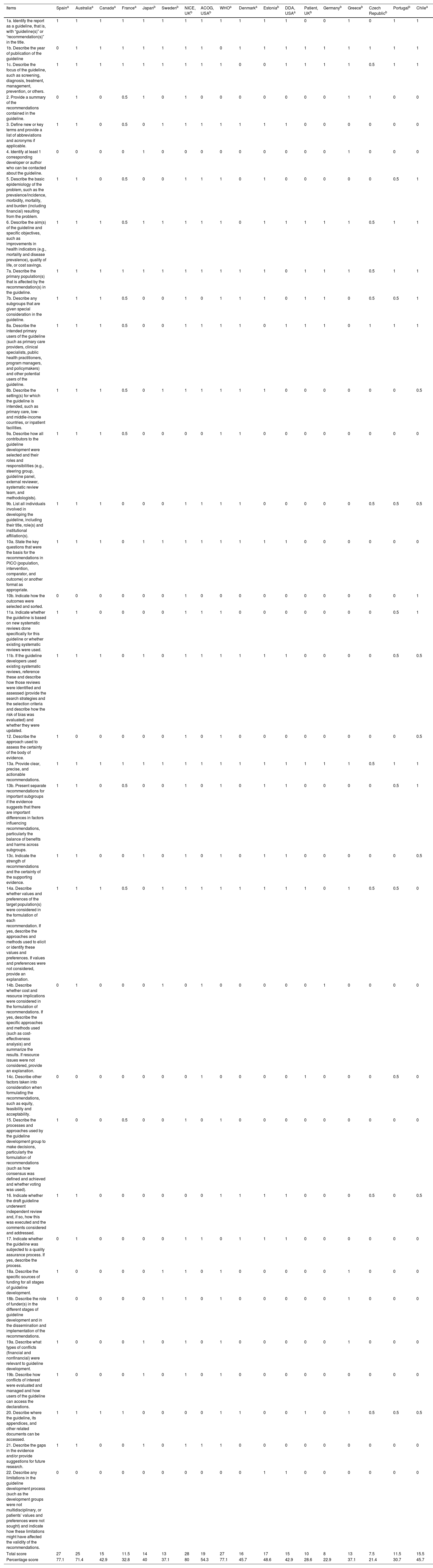

Methodological and reporting quality assessment was evaluated in the included CPGs using AGREE II14 tool (possible score range 22–161), while quality reporting was assessed using RIGHT tool (possible score range 0–35).15 AGREE II consists of 23 items grouped into 6 domains (scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity and presentation, applicability and editorial independence). Each of the 23 items is rated on a 7-point scale, where 1 indicates “Strongly Disagree” and 7 indicates “Strongly Agree”. RIGHT tool includes 22 reporting items organized into 6 domains. Each of the 22 items is evaluated based on whether it is adequately reported, typically rated as “Yes,” “No,” or “Partially”. Two authors (MMRA and MRRG) independently rated each CPGs. Major discrepancies in the scores (where assigned scores differed by more than two points) were discussed and independently reassessed by the third author (NCI). Domain scores were calculated, whereby a total quality score was obtained for each domain by summing the score of each item. The mean domain score (between the two raters) was used to standardize the domain score as a percentage.

Statistical analysisThe overall and stratified frequency distributions for the items considered, categorized by document type, were calculated. For the AGREE II and RIGHT tools, measures of central tendency (mean) and dispersion (standard deviation) were computed for both absolute and percentage scores. CPGs meeting two-thirds (scoring 67% or above) of the total items, were regarded as high quality. All calculations were performed using STATA 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

ResultsLiterature selectionA total of 2177 citations were initially identified (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, 1013 titles and abstracts were screened. Fifty potentially relevant full-text articles were reviewed, of which only three met the inclusion criteria. An additional 12 CPGs were identified from the references of these documents. Moreover, three CPGs were obtained directly from specialized organizations’ websites. Finally, 18 consensus statements, CPGs, or recommendations met the inclusion criteria and were included in this SR. Table A.2. includes the reasons for excluding documents after full-text review.

CPG characteristicsThe characteristics of each CPGs are provided in Table 1. A total of 18 CPGs related to antenatal care were identified from various HIC. The CPGs originated from Europe (n=11, 61.1%)19-21; United States (n=2, 11.1%),22,23 Canada (n=1, 5.6%),24 Australia (n=1, 5.6%),25 Japan (n=1, 5.6%),26 Chile (n=1, 5.6%),27 and WHO (n=1, 5.6%)7. Most of the CPGs were developed by government health departments or professional medical associations and were delivered from 2014 to 2024. The CPGs were Antenatal Clinical Care Practice Guidelines (ACCPGs) (n=10, 55.5%),19,21-29 consensus recommendations (CR) (n=6, 33.3%)20,30-33 and recommendations of best practices (RBP) (n=2, 12.96%).34,35 Some CPGs (n=11, 61.1%)21,22,24-27,30,34 specified the version of the registry, with updates ranging from second to tenth editions. Most of the CPGs were unpublished in peer-reviewed journals (n=15, 83.3%), with only three being published in medical journals.25,26,32

Characteristics of Clinical Practice Guidelines (n=18).

| Name | Year | Type of document | Organization/Society/authors | Edition | Journal of publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO: Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience | 2016 | CR | WHO | No data | Not published |

| Clinical Practice Guideline for Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Postpartum | 2014 | ACCPG | Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs, and Social Services | No data | Not published |

| Clinical Practice Guideline | 2020 | ACCPG | Australian Government Department of Health | 4th. | Medical Journal of Australia |

| Family-centred maternity and newborn care | 2020 | ACCPG | Public Health Agency of Canada | 5th. | Not published |

| Suivi et orientation des femmes enceintes en fonction des situations à risque identifiées | 2016 | RBP | French National Authority for Health | No data | Not published |

| Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition | 2020 | ACCPG | Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) | Update 2017 | The journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology research |

| Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa | 2016 | CR | Swedish Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (SFOG): Association of Maternal-Child Health Psychologists | 2nd. | Not published |

| Antenatal Care UK | 2021 | ACCPG | United Kingdom: National Institute for Care and Excellence (NICE) | Update 2008 | Not published |

| Guideline for Perinatal Care | 2016–2017 | ACCPG | United States: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) | 8th. | Not published |

| Svangreomsorgen | 2022 | CR | Danish Health Authority (Sundhedsstyrelsen) | Update 2013 | Not published |

| Aseduse jälgimise juhend | 2018 | ACCPG | Estonian Society of Gynecologists | Update 2011 | Not published |

| VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of pregnancy | 2018 | ACCPG | United States: Department of Defense | No data | Not published |

| Antenatal Care | 2021 | CR | United Kingdom Medical Association. Patient® | No data | Not published |

| Prenatal care in Germany: which medical examinations are officially recommended in the guidelines: Mutterschaftsrichtlinie | 2023 | CR | German Federal Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians | 10th. | Fortschritte der medizine |

| Antenatal care guidelines | 2018 | ACCPG | Greece: Doctors of the World (organization) and MSD (pharmaceutical company) | No data | Not published |

| Principles of Care in Obstetric Assistance | 2021 | CR | Czech Republic: Union of Midwives | No data | Not published |

| Guideline for Best Practices: Pregnancy and Adaptation to Low-Risk Pregnancy | 2023 | RBP | Portuguese Nurses’ Association | 1st. | Not published |

| Perinatal Guide | 2015 | ACCPG | Chilean Ministry of Health | 1st. | Not published |

Abbreviations: WHO: World Health Organization; CR: consensus recommendation; ACCPG: Antenatal Care Clinical Practice Guidelines; RBP: Recommendation of Best Practices.

The Czech33 CPG received the lowest score on both tools, the WHO7 CPG ranked highest according to AGREE II, and the NICE21 CPG achieved the highest score according to RIGH (Tables 2 and 3). Using the AGREE II (observed score range was between 51.5 and 145) showed that institutional CPGs had an average score of 107.4±26.8 vs. 86.2±26.1 (p=0.0218) for professional society CPGs. In contrast, institutional CPGs had an average score of 19.1±6.2, while CPGs developed by professional societies scored an average of 14.1±6.1 (p=0.0201) for RIGHT (observed score range was between 7.5 and 28). Fig. 2 shows a correlation in the percentage scores for the CPGs (AGREE II and RIGHT r=0.94). High-quality CPGs were 6/18 using AGREE II (Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, U.S.A.-ACOG, WHO, and Denmark)7,19,21,22,25,31 and 4/18 using RIGHT (Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, and WHO).7,19,21,25 The CPGs published in peer-reviewed scientific journals were not associated with high quality. The two highest-scoring CPGs, WHO and the UK-NICE, have not been published in scientific journals.7,21 The year of CPG publication showed no association with quality. The Spanish CPG was the oldest19 and received one of the highest scores.

Clinical Practice Guidelines scores from the AGREE II tool.

| Spaina | Australiaa | Canadaa | Francea | Japanb | Swedenb | NICE, UKb | ACOG, USAb | WHOa | Denmarka | Estoniab | DDA, USAa | Patient, UKb | Germanyb | Greeceb | Czech Republicb | Portugalb | Chilea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The overall objective(s) of the guideline is (are) specifically described. | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| 2. The clinical question(s) covered by the guideline is (are) specifically described. | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 7 |

| 3. The patients to whom the guideline is meant to apply are specifically described. | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 4. The guideline development group includes individuals from all the relevant professional groups. | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 5. The patients’ views and preferences have been sought. | 6 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 6. The target users of the guideline are clearly defined. | 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| 7. The guideline has been piloted among end users. | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 8. Systematic methods were used to search for evidence. | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 9. The criteria for selecting the evidence are clearly described. | 6 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. The methods for formulating the recommendations are clearly described. | 7 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 11. The health benefits, side effects, and risks have been considered in formulating the recommendations. | 5 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| 12. There is an explicit link between the recommendations and the supporting evidence. | 7 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| 13. The guideline has been externally reviewed by experts prior to its publication. | 7 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 14. A procedure for updating the guideline is provided. | 4 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| 15. The recommendations are specific and unambiguous. | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 7 |

| 16. The different options for management of the condition are clearly presented. | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 17. Key recommendations are easily identifiable. | 6 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| 18. The guideline is supported with tools for application. | 6 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 19. The potential organizational barriers in applying the recommendations have been discussed. | 1 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 20. The potential cost implications of applying the recommendations have been considered. | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 21. The guideline presents key review criteria for monitoring and/or audit purposes. | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 22. The guideline is editorially independent from the funding body. | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 23. Conflicts of interest of guideline development members have been recorded. | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Total score | 133 | 127 | 91 | 63 | 102 | 94 | 131 | 110 | 145 | 110 | 104 | 99 | 70 | 65 | 69 | 51.5 | 63.5 | 91 |

| Percentage score | 82.6 | 78.9 | 56.5 | 39.13 | 63.3 | 58.4 | 81.4 | 68.3 | 90.1 | 68.3 | 64.6 | 61.5 | 43.5 | 40.4 | 42.8 | 32 | 39.4 | 56.2 |

Clinical Practice Guidelines scores from the RIGHT tool.

| Items | Spaina | Australiaa | Canadaa | Francea | Japanb | Swedenb | NICE, UKb | ACOG, USAb | WHOa | Denmarka | Estoniab | DDA, USAa | Patient, UKb | Germanyb | Greeceb | Czech Republicb | Portugalb | Chilea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a. Identify the report as a guideline, that is, with “guideline(s)” or “recommendation(s)” in the title. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1b. Describe the year of publication of the guideline | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1c. Describe the focus of the guideline, such as screening, diagnosis, treatment, management, prevention, or others. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 2. Provide a summary of the recommendations contained in the guideline. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Define new or key terms and provide a list of abbreviations and acronyms if applicable. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Identify at least 1 corresponding developer or author who can be contacted about the guideline. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Describe the basic epidemiology of the problem, such as the prevalence/incidence, morbidity, mortality, and burden (including financial) resulting from the problem. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 6. Describe the aim(s) of the guideline and specific objectives, such as improvements in health indicators (e.g., mortality and disease prevalence), quality of life, or cost savings. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 7a. Describe the primary population(s) that is affected by the recommendation(s) in the guideline. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 7b. Describe any subgroups that are given special consideration in the guideline. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 8a. Describe the intended primary users of the guideline (such as primary care providers, clinical specialists, public health practitioners, program managers, and policymakers) and other potential users of the guideline. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8b. Describe the setting(s) for which the guideline is intended, such as primary care, low- and middle-income countries, or inpatient facilities. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 9a. Describe how all contributors to the guideline development were selected and their roles and responsibilities (e.g., steering group, guideline panel, external reviewer, systematic review team, and methodologists). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9b. List all individuals involved in developing the guideline, including their title, role(s) and institutional affiliation(s). | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 10a. State the key questions that were the basis for the recommendations in PICO (population, intervention, comparator, and outcome) or another format as appropriate. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10b. Indicate how the outcomes were selected and sorted. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 11a. Indicate whether the guideline is based on new systematic reviews done specifically for this guideline or whether existing systematic reviews were used. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 11b. If the guideline developers used existing systematic reviews, reference these and describe how those reviews were identified and assessed (provide the search strategies and the selection criteria and describe how the risk of bias was evaluated) and whether they were updated. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 12. Describe the approach used to assess the certainty of the body of evidence. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 13a. Provide clear, precise, and actionable recommendations. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 |

| 13b. Present separate recommendations for important subgroups if the evidence suggests that there are important differences in factors influencing recommendations, particularly the balance of benefits and harms across subgroups. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 13c. Indicate the strength of recommendations and the certainty of the supporting evidence. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 14a. Describe whether values and preferences of the target population(s) were considered in the formulation of each recommendation. If yes, describe the approaches and methods used to elicit or identify these values and preferences. If values and preferences were not considered, provide an explanation. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 14b. Describe whether cost and resource implications were considered in the formulation of recommendations. If yes, describe the specific approaches and methods used (such as cost-effectiveness analysis) and summarize the results. If resource issues were not considered, provide an explanation. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14c. Describe other factors taken into consideration when formulating the recommendations, such as equity, feasibility and acceptability. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 |

| 15. Describe the processes and approaches used by the guideline development group to make decisions, particularly the formulation of recommendations (such as how consensus was defined and achieved and whether voting was used). | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16. Indicate whether the draft guideline underwent independent review and, if so, how this was executed and the comments considered and addressed. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| 17. Indicate whether the guideline was subjected to a quality assurance process. If yes, describe the process. | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18a. Describe the specific sources of funding for all stages of guideline development. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18b. Describe the role of funder(s) in the different stages of guideline development and in the dissemination and implementation of the recommendations. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19a. Describe what types of conflicts (financial and nonfinancial) were relevant to guideline development. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19b. Describe how conflicts of interest were evaluated and managed and how users of the guideline can access the declarations. | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20. Describe where the guideline, its appendices, and other related documents can be accessed. | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 21. Describe the gaps in the evidence and/or provide suggestions for future research. | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22. Describe any limitations in the guideline development process (such as the development groups were not multidisciplinary, or patients’ values and preferences were not sought) and indicate how these limitations might have affected the validity of the recommendations. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total score | 27 | 25 | 15 | 11.5 | 14 | 13 | 28 | 19 | 27 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 7.5 | 11.5 | 15.5 |

| Percentage score | 77.1 | 71.4 | 42.9 | 32.8 | 40 | 37.1 | 80 | 54.3 | 77.1 | 45.7 | 48.6 | 42.9 | 28.6 | 22.9 | 37.1 | 21.4 | 30.7 | 45.7 |

Table 4 shows that only one CPG addressed recommendations regarding the duration of counselling.24 12/18 CPGs provide supporting materials to standardize dietary advice.7,19–21,24,25,27–31,34 7/18 CPGs recommend that diet counseling should also be delivered in group sessions.7,23–25,27,29,31 Eight CPGs suggest adjusting dietary intake, leaving the specifics to the judgment of the healthcare professional.7,19,21,23,26,32,35 Only CPGs from Sweden, Chile, and Australia recommend restricting sugar consumption.25,27,30,33 Eight CPGs provide lists or types of foods to avoid20,24,25,27–30,34 and some include links to societies or institutional recommendations, which may or may not be specific to pregnant women.21,24,25,28,30,31

Nutritional counseling on Clinical Practice Guidelines (n=18).

| Name | SupplementationA, B, C, D, E* | Provides materials for nutritional counseling | Recommends group sessions | Dietary intake recommendations | Chemical risks (Hg) | Biological risks (Li, Tx, Sa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO: Recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience | A, B | Yes | Yes | Healthy eating and physical activity are recommended during pregnancy to maintain health and prevent excessive weight gain. For undernourished populations, balanced energy and protein dietary supplements are advised, but high-protein supplementation is not recommended | No | No |

| Clinical Practice Guideline for Pregnancy, Childbirth, and Postpartum | A, C, E | Yes | No | Adjust caloric intake to meet pregnancy needs. Do not routinely recommend high-protein diets for pregnant women. Advise protein-energy restriction for those with excess weight gain or overweight during pregnancy, following American Dietetic Association guidelines. Provide additional energy (2200–2900kcal) for the 2nd and 3rd trimesters, and create a dietary plan considering age, physical activity, and weight gain. | No | Tx |

| Clinical Practice Guideline | A, B, C | Yes | Yes | Specifies daily servings for major food groups and lists foods to consume with caution. It includes a link to the national website: https://www.eatforhealth.gov.au, based on the Australian Dietary Guidelines NHMRC 2013. The website offers advice and materials for educators and consumers on nutrition across all life stages. | Limit the intake of some fish species | Li, Tx |

| Family-centred maternity and newborn care | A, B, C, D | Yes | Yes | Provides links to additional resources: Prenatal Nutrition offers food safety information, including foods to avoid and safer alternatives. Canada's Food Guide provides general dietary recommendations such as consuming vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats, and beverages, along with examples of healthy snacks and budget-friendly meal options. Mercury in Fish offers guidance on safe fish consumption related to mercury. | Limit the intake of some fish species | Li, Tx |

| Suivi et orientation des femmes enceintes en fonction des situations à risque identifiées | A | No | No | Emphasizes the importance of following a balanced and varied diet. It does not include additional materials. | No | No |

| Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition | A | No | No | Emphasizes the importance of following a balanced and varied diet. It does not include additional materials. | No | No |

| Mödrahälsovård, Sexuell och Reproduktiv Hälsa | B, D | Yes | No | Includes high intake of fruits and vegetables, increase fish consumption, incorporate more whole grains, switch to vegetable fats, and restrict salt, sugary drinks, and sweets. The guideline refers to a non-functional link to the National Center for Women's Safety (Nationellt centrum för kvinnofrid) at http://www.nck.uu.se/kunskapsbanken. A functional alternative can be found at Swedish Food Agency, which provides dietary recommendations for pregnant women rather than professionals. | No | No |

| Antenatal Care UK | No | No | No | Highlights the importance of establishing healthy nutritional habits. The document refers to the maternal and infant nutrition guide for professionals available at NICE PH11. This resource provides general guidelines without accompanying support materials. | No | No |

| Guideline for Perinatal Care | A, B, D | No | No | Women should receive information focused on an individualized nutritional eating plan that aligns with their access to food and dietary preferences. Special attention should be given to low-income women. If needed, referral to a nutritionist is advised. No additional materials are provided. | Recommend the intake of fish | Li, Tx |

| Svangreomsorgen | A, B, D | Yes | Yes | Pregnant women are advised to increase their intake of fruits and vegetables, reduce meat consumption, and consume more fish and legumes. They should also opt for whole grain cereals and cut back on sugary, fatty, and/or salty foods. Specifically, it is recommended to eat 350g of fish per week, including 2000g of fatty fish, with guidance on recommended fish species provided. Additionally, official dietary guidelines from the Danish Food Agency can be found at Danish Food Agency Guidelines. Note that the website Sundhed.dk offers general recommendations not specifically targeted at professionals. | Yes | No |

| Aseduse jälgimise juhend | A, D | Yes | No | Pregnant women have increased energy needs that vary by trimester. Ensuring food safety is crucial, and although the provided instructions are general, a list of foods to avoid is included. Includes some resources: Nutrition and Physical Activity Recommendations (access the document without a password under ‘Eesti toitumis- ja liikumissoovitused 2015’). These recommendations focus on improving general habits and are not specifically targeted at professionals. | No | No |

| VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline for the management of pregnancy | A, D | No | Yes | Women should follow a balanced and varied diet. No additional materials are provided. | No | No |

| Antenatal Care | A, D | No | No | Recommend a balanced and varied diet. A list of foods to avoid is provided. | Recommend the intake of fish | Li, Tx |

| Prenatal care in Germany: which medical examinations are officially recommended in the guidelines: Mutterschaftsrichtlinie | C | No | No | Recommend a balanced and varied diet. A list of foods to avoid is provided. | No | No |

| Antenatal care guidelines | A, B, D | Yes | Yes | Nutritional counseling is recommended, and a list of foods to avoid is provided. No additional complementary materials are included. General food hygiene is considered, but specific guidelines are not offered. | No | Li, Tx |

| Principles of Care in Obstetric Assistance | No | Si | Si | Only indicates that nutrition advice should be offered. | No | No |

| Guideline for Best Practices: Pregnancy and Adaptation to Low-Risk Pregnancy | A, B, C, E | Si | No | Includes some tips for giving in a repeated way during visits. | Hg, ftalatos, Pb, pesticides | Li, Tx, Sa |

| Perinatal Guide | A, B, E | Si | Si | Describe nutritional recommendations (caloric intake, vitamins, minerals, …) to provide repeatedly. | Hg | Li,Tx |

Abbreviations: WHO: World Health Organization; Hg: mercury; Li: Listeria; Tx: Toxoplasmosis; Sa: Salmonella.

Mercury, primarily from fish, was identified as a key chemical risk in 7 CPGs.20,22,24,25,27,31,34 Microbiological risks were generally limited to Toxoplasma and Listeria; 7 CPGs addressed both risks.20,22,24,25,27,29,34 Only Toxoplasma was noted in Spanish CPG.19Salmonella was only mentioned in the Portuguese CPG.34 There were no specific recommendations for food preparation, storage, or precautions related to ready-made meals, except in the Canadian CPG.24 The CPGs with the most detailed dietary advice, either directly or through hyperlinks to specific resources, were from Australia,25 Sweden,30 Canada,24 Chile,27 Estonia28 and Denmark.31

Fourteen CPGs recommend folic acid supplementation without specifying the start time7,19,20,22-29,31,34,35 with Canada's CPGs recommending it in high-risk situations, and the others suggesting it systematically. Iron supplementation was addressed by 9 CPGs,7,22,24,25,27,29-31,34 while iodine supplementation was covered by 5.19,24,25,32,34 Recommendations for other vitamins (A, C, D) and micronutrients (Ca, Zn) were varied, with the Australian providing the most comprehensive coverage.25 Only the CPGs from Canada24 and the U.S. Department of Defense23 advocated for a multivitamin complex. Conversely, the CPGs from Spain,19 Portugal34 and Chile27 specifically advised against the widespread use of these supplements.

Overview of other obstetric recommendations in CPGsTable A.3. summarizes general care recommendations from the included set of 18 CPGs. The recommended number of visits ranged between 619 and 17.26 Two CPGs specify recording anthropometric data only at the first visit,24,29 1 CPG recommended weight monitoring based on the gestational week,19 and 5 stipulated that weight should be checked at each visit.23,25-27,35 The remaining 10 CPGs recommended weight monitoring with variable or unspecified frequency. Blood pressure monitoring was deemed essential at each visit in 13/18 CPGs.19,20,22-27,29 Conversely, 4 CPGs outlined various approaches to blood pressure monitoring throughout pregnancy.21,32,33,34 WHO7 guideline did not include routine blood pressure checks, but emphasized regular surveillance for edema, without specifying the frequency. This recommendation was supported by other 5 CPGs,22,26-28,34 which suggested monitoring at each visit starting from the sixteenth week,26 until the third trimester.28 Regarding ultrasounds, CPGs generally recommended two scans during pregnancy, one in the first trimester and another in the second trimester. However, 6 CPGs advocated for three ultrasounds, with one per trimester.26,27,32-35 In contrast, only 1 CPG proposed a single ultrasound before 24 weeks of gestation.7

DiscussionMain findingsThis systematic review assessed the methodological and reporting quality of CPGs regarding nutritional counselling recommendations in healthy pregnant women from HIC, in the last decade. The review identified 18 CPGs. Just under two-thirds of the evaluated CPGs demonstrated medium to high quality as assessed by the RIGHT and AGREE II frameworks. Institutional CPGs scored significantly better than those from professional societies. The variability of the content within these recommendations suggests that the CPG development process was not uniform.

Strengths and limitationsThe key strength of the present study lies in its systematic approach as demonstrated in the PRISMA checklist (Table A.4.). Extensive search was conducted on multiple databases. Documents selected from these sources were examined for their reference lists. In addition, Google Scholar was searched to examine grey literature looking for governmental websites and other sources of CPGs not typically covered in bibliographic databases. The identification of only a few CPGs may, on the face of it, suggest that additional relevant CPGs are likely to exist but remain unlocated. However, it has been noted by Iannuzzi et al.36 that some countries do not perceive the need for a national consensus on prenatal care recommendations, leading to the absence of standardized CPGs in these countries. Therefore, we can be confident that CPGs on antenatal care are limited in HIC settings. A previous study had also found that prenatal care CPGs were few.13 Our methodological and reporting quality of CPGs for prenatal care on nutritional counselling results represent high-income countries, but not middle- or low-income countries.

InterpretationOur results showed that with AGREE II, six high-quality CPGs were identified from Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, U.S.A.-ACOG, WHO, and Denmark. Using the RIGHT tool, four high-quality CPGs were identified from Spain, Australia, UK-NICE, and WHO. Key aspects of care for pregnant women include social support, timely information, clinical care, and adapting to their needs. We found inconsistencies in dietary recommendations across CPGs,26,29,32,33,35 especially concerning diet modification. Nutritional advice is often limited to early visits, focusing on foods to avoid, with broader guidance left to midwives and primary care providers who may lack specific training. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, most pregnancy-related research has focused on the virus and vaccines, with limited attention to nutrition. Significant gaps also exist in preventive care related to sleep25,28,31,34 and infections from Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and Campylobacter, which are absent in most CPGs, despite their link to miscarriage and low birth weight.37–39 Abalos et al.5 noted broad support for infectious disease screenings, consistent with our findings for HIV (87%) and hepatitis B (73%). However, our review showed higher support for group B streptococcus screening (80%) compared to Abalos’ report. Early ultrasound was recommended in 94.4% of our reviewed CPGs, compared to 67% in Abalos et al.5

ConclusionThe methodological and reporting quality of CPGs, which include nutritional counselling from HIC, varied significantly between institutional CPGs, which generally scored better, and those from professional societies. These findings underscore the need for standardized quality assessment in the development and reporting of CPGs to ensure clear, actionable, and evidence-based recommendations, especially in nutrition advice.

CRediT authorship contribution statementA. Bueno-Cavanillas and M.R. Román-Gálvez conceived the study. A. Bueno-Cavanillas and M.M. Rivas-Arquillo designed the study protocol. M.M. Rivas-Arquillo and M.R. Román-Gálvez conducted the literature search. M.M. Rivas-Arquillo, M.R. Román-Gálvez, and N. Cano-Ibáñez selected the studies and extracted the relevant information. M.M. Rivas-Arquillo and M.R. Román-Gálvez synthesized the data. M.M. Rivas-Arquillo and N. Cano-Ibáñez wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. A. Bueno-Cavanillas, Khalid S. Khan, and C. Amezcua-Prieto critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript and accept full responsibility for its content as published.

Ethical considerationsThis study is a systematic review of existing literature. Consequently, ethical approval was not required. All included studies were conducted in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and have been cited appropriately.

FundingThis research was developed under the project funded by Instituto Salud Carlos III, grant number PI23/01866, with financial support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and co-funding from the European Union. The funder had no role in the design, analysis, or interpretation of the research and manuscript, nor did they participate in the research process following the provision of funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

K.S.K. is funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senior modality) Program grant, given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Spanish Government.