Public partnerships, a route to sharing expertise, networks and resources anchored in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, has been championed by multiple stakeholders.

ObjectiveTo propose a new evidence-based medicine (EBM) curriculum for harnessing patient and public expertise to ensure that EBM teaching and learning can become more relevant and impactful.

MethodsA curriculum development group comprising of EBM teachers, patient and public involvement representatives, clinicians, clinical epidemiologists, public health experts and educationalists, with experience of delivering and evaluating face-to-face and online EBM courses across many countries and continents, prepared a new EBM course.

ResultsA student-centred, problem-based and clinically integrated course for teaching and learning EBM was developed. In the spirit of shared decision-making, practitioners can learn to support patients, articulate their perspectives, recognise the need for their contribution and ensure community involvement when generating and applying evidence. With end users in mind, the application of research findings, delivery of care and EBM effectiveness in the workplace would carry increased priority.

ConclusionsEmbracing patients as EBM collaborators can help deliver cognitive diversity and inspire different ways of thinking and working. Adopting the proposed approach in EBM education lays the foundations for a joint practitioner–patient partnership to ask, acquire, appraise and apply EBM in a more holistic context which will strengthen the EBM proposition.

Las asociaciones de pacientes y ciudadanos constituyen una vía para compartir experiencias, redes y recursos siendo promovidas por los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible de la Organización de Naciones Unidas (ONU), y defendidas por todas las partes y sectores interesados.

ObjetivoProponer un nuevo plan de estudios de medicina basada en la evidencia (MBE) para aprovechar la experiencia de los pacientes con el fin de garantizar de que la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la MBE sean más relevantes e impactantes.

MétodosUn grupo de expertos compuesto por profesores del área de MBE, representantes de pacientes, médicos, epidemiólogos clínicos, expertos en salud pública y pedagogos, con experiencia en la impartición y evaluación de cursos de MBE presenciales y online en el ámbito internacional, desarrolló e implementó un curso de MBE.

ResultadosSe desarrolló un curso centrado en el estudiante, basado en problemas y clínicamente integrado para la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de la MBE. En el espíritu de la toma de decisiones compartida, los profesionales pueden aprender a apoyar a los pacientes, a articular sus perspectivas, a reconocer la necesidad de su contribución y a garantizar la participación de la comunidad a la hora de generar y aplicar las pruebas. La aplicación de los resultados de la investigación, la prestación de cuidados y la eficacia de la MBE en el lugar de trabajo son las áreas de mayor prioridad para los asistentes.

ConclusionesAdoptar a los pacientes como colaboradores de la MBE puede ayudar a proporcionar diversidad cognitiva e inspirar diferentes formas de pensar y trabajar. La adopción del enfoque propuesto en la formación en MBE sienta las bases para una colaboración conjunta entre profesionales y pacientes para preguntar, adquirir, valorar y aplicar la MBE en un contexto más holístico que reforzará la propuesta de MBE.

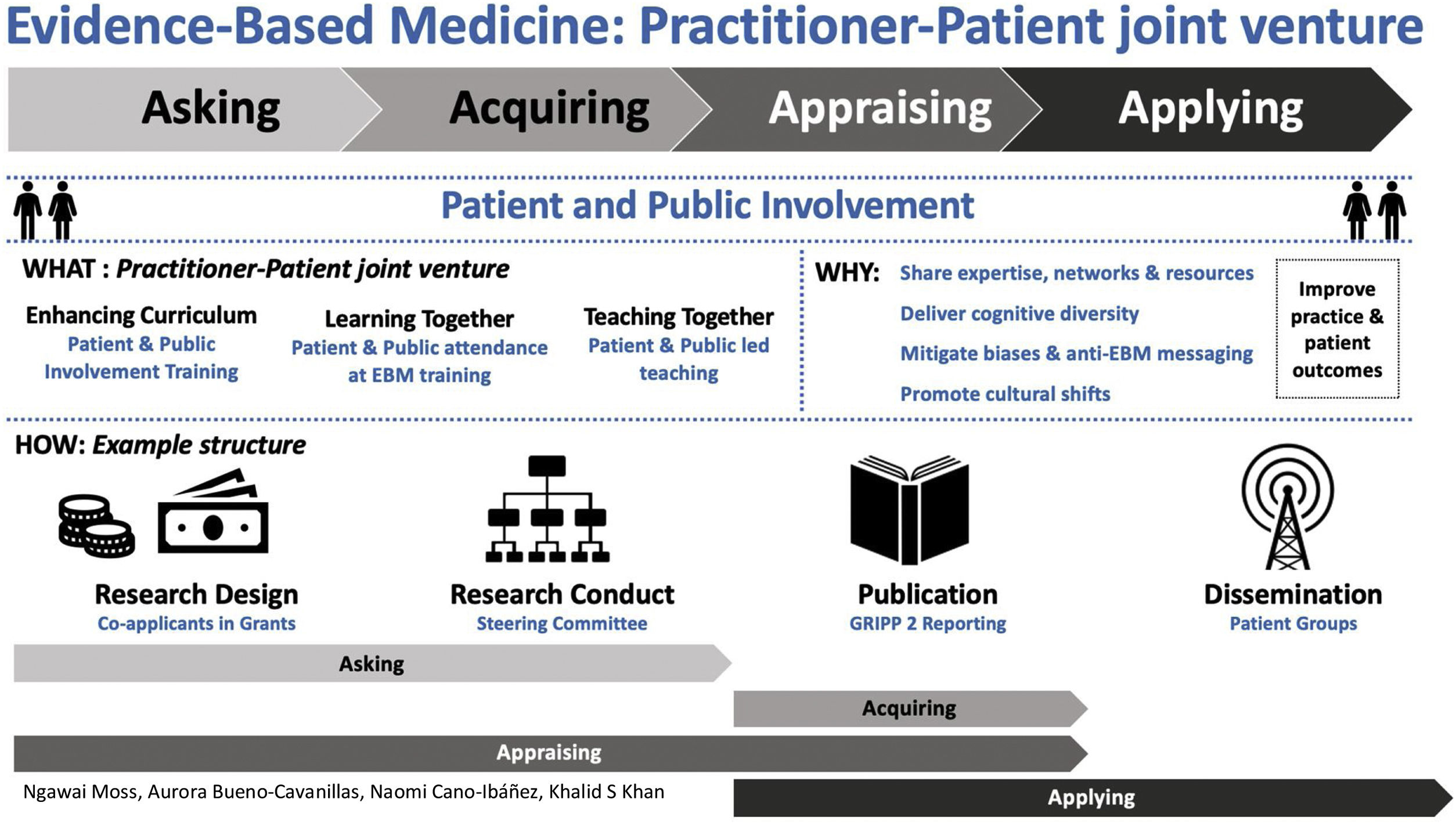

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) emphasises a framework for action in the clinical setting that relies on asking the right questions, acquiring literature, appraising its validity and applying current, best evidence in practice. We suggest adapting the EBM curricula to enable practitioners to more effectively involve patients and the public in practice, inviting them to learn together and even help teach. This interdisciplinary approach can help mitigate existing biases in EBM.1 As institutional objectives increasingly favour patient and public partnership, practitioner–patient collaborations can take advantage of this shift increasing EBM adoption and implementation. Patient involvement is a developing field, with many imperfections for example there can be potential for conflicts of interests, lack of diversity, and resourcing issues.2 The evidence base for patient involvement is at present weak3 and the current EBM approaches are not as patient centred as they might be.1 No doubt, future research will generate evidence on how patient involvement can best add value. By diversifying EBM teaching and learning activities from practitioner knowledge and skill in critical appraisal,4 to embrace a practitioner–patient joint venture, we can harness cognitive diversity5,6 and bring about cultural shifts,7 with the ultimate objective to improve practice and outcomes in the real world.

Health professional driven EBM can be improvedThe daily professional demands on practitioners have always been the obstacle that impedes their ability to access, digest and implement EBM. Even EBM champions are hindered by an entrenched infrastructure that is not designed to accommodate EBM.8 Health professionals in managerial roles, seeking to embed EBM in a top down approach, are challenged by their workforce's time availability. Providing clinical librarians9 to assist and teach practitioners in on-the-job EBM have not necessarily been universally welcome interventions.9,10

A partnership with patients and the public could establish “Common ground on what their problem was and to seek a mutual agreement on the method ofmanagement”,11 addressing resistance from key decision-makers to back EBM. Their support would lend credibility and increase the possibility of deriving real value from it. Criticism highlighting EBM community deficiencies to “involve” and “empower” patients1 could be challenged while offering an opportunity to build interest, capacity and a body of evidence on the best methods to achieve effective patient involvement12,13 and shared-decision making.1

Patients can revitalise EBMPatients as ‘consumers’ are able to identify, propose and advocate for the modernisation of infrastructure and changes to health care policy and guidance.14 While their ‘added value’ and ‘limitations’ may be difficult to quantify, these patient interests can drive change on the ground and directly influence health outcomes. Patients can be motivated to keep asking questions, generate petitions, use their own lived examples to generate media interest or initiate inquiries and guideline changes. Patient advocacy can generate positive changes that could have been previously addressed but were not. From Sodium Valproate in pregnancy15 to the antivaccine movement and the rise of fake news patients are in an influential position to embed or hinder EBM into the fabric of society. This is particularly relevant when EBM as a pillar is government sponsored or subsidised.2 Limited resources relative to the increasing expectations and demands of patients (e.g. access, appropriateness, effectiveness) require EBM to be the rationalising tool that adjudicates objectively and fairly. To enable informed advocacy, patients should have a basic understanding of EBM. More importantly, practitioners have a responsibility to learn about how to enable patients to become their partners in embedding EBM.

Global interconnectedness has highlighted that partnerships enable a systemic route to unite and leverage complementary expertise that can be transformative.16 As subject matter experts, patients and the public can play a significant and valuable role in research.17 For example, patients can interrogate and give meaning to an idea when building a proposal or minimise unnecessary disturbances for patient participants to improve adherence during a trial.13 EBM, naturally being a research-based discipline, ought to follow a logical framework to mitigate some potential EBM biases that devalue the patient agenda,1 generate sustained improvements in healthcare or hold decision-makers to account if EBM is not practised. To effectively and consistently engage, involve and manage EBM patient collaborations, a new EBM curriculum is essential to cultivate, utilise and normalise practitioner–patient EBM joint venture for the collective value of the community.

A new facilitative curriculum outlineWe propose a curriculum targeting EBM practitioners applying evidence in common clinical settings. The curriculum development group comprised EBM teachers, patient and public involvement representatives, clinicians, clinical epidemiologists, public health experts and educationalists with experience of delivering and evaluating face-to-face and online EBM courses across many countries and continents (Appendix 1). We incorporated themes from existing standards for public involvement in research18 and reviews19 and applied established curriculum development methodology.20 The feedback obtained from two pilot courses in 2020–21 in the University of Granada Doctoral School allowed revisions to refine the initial learning objectives and teaching content. The participants feedback demonstrated that prior to the course the majority had little or no knowledge of the topic and after the course there was enhancement of knowledge (pre-course little or no knowledge 7/9, 77%; post-course this figure was 0/9; p=0.003). The course content was evaluated as good or very good knowledge by the majority (6/9, 67%). The curriculum outline presented is meant to be: student-centred, permitting learners to take responsibility; problem-based, focusing learning activities on patient-relevant problems; integrated, easily incorporated in the clinical setting; community-based, involving patients and citizens in science; elective, flexibly delivered; and, systematic, cognate with current courses.10

Conceptualised in Fig. 1 is where patient related roles are mapped to each EBM step. The learning needs identified are framed as educational objectives as outlined in Table 1. These are intended to be facilitative rather than prescriptive, they provide a baseline which can be adapted or used to co-produce13,21 a more extensive programme. Put simply, as patient involvement in research adds value to its design, study conduct, article publication and result dissemination, these aspects should be embedded1 in educational objectives for EBM teaching and learning per step as follows:

A proposed curriculum outline for practitioner–patient joint venture in evidence-based medicine (EBM).

| Objective: To enable practitioners to effectively involve patients and the public in EBM | ||

| Lesson plan | ||

| What practitioners need to be able to do | What practitioners need to know | |

| Module 1Asking questions | 1) Involve patients in:• Identifying and prioritising research topics• Framing the research question (e.g. outcome assessment)• Assessing patient acceptability and compliance with interventions2) Tap into pockets of engaged patients and members of the public (e.g. advisory groups)3) Elicit patient preferences, behaviour patterns, disruptors to gain depth of understanding to identify the strengths and weaknesses of a question4) Identify and harness patient experience, interest, skills and networks5) Document and record patient and public involvement | Awareness of:- Patient diversity, breadth of perspectives and literacy- The spectrum of patient involvement roles and activities- Citizen Science, patient generated data (e.g. wearable technology) and predictive analytics- Discussion groups and independent facilitation- Shared understanding of terminology- Resources outlining best practices for patient and public involvement (e.g. UK Standards for Public Involvement) |

| Module 2Acquiring literature | 1) Alter medical writing to:• Embed plain language• Generate patient friendly medical summaries2) Enable patients and the public to:• Gather different types of evidence (e.g. patient friendly search engines, open access)• Sift through the volume of evidence• Become authors and be recognised for their expertise3) Identify themes that are of increasing interest to patients and the public4) Explain indicators and variations in evidence quality and reliability to patients and the public | Awareness of:- Access (and lack of access) to relevant literature- Literature uses (e.g. to make decisions, fine tune health care) |

| Module 3Appraising literature | 1) Help patients and the public:• Identify relevant evidence• Analyse evidence from diverse sources• Highlight gaps in evidence2) Enable patients and the public to consider and interpret different types of evidence (from their perspective)3) Elicit patient-driven insights that are most likely to create impact when applying findings4) Evaluate involvement of patients and the public in research (e.g. GRIPP2)5) Make evidence easily understood and ‘ready to use’ | Awareness of:- Peer review by patients and the public- Patients and the public undertaking library-based research and digital investigations (e.g. overlapping demographic, economic, weather data etc.)- Levels of impact for patients and society |

| Module 4Applying findings | 1) Make evidence ‘consumable’ so all stakeholders can digest it and identify value added activity2) Collaborate and empower patients and the public to enable EBM:• Understand their motivation• Distill key messages (e.g. communication of evidence, specify how findings can be applied)• Generate ways to visualise what applying findings means ‘in real life’ (e.g. case study or patient narrative)• Identify specific actions they can take and support them in doing this (e.g. joining a committee, speaking at stakeholder meetings)• Leverage their networks and access (e.g. identifying and engaging decisionmakers and sponsors to apply EBM into practice)3) Focus on problem solving identifying where the evidence is most likely to create patient benefit and solve stakeholder issues (e.g. faster streamlined processes)4) Embed anchors and communicate these to patients and the public so they can use them as leverage (e.g. build the ‘application of findings’ into reporting frameworks, audits, processes)5) Incorporate shared decision making into practice at patient level | Awareness of:- Range of stakeholders and communication needs (e.g. patient groups and civil society organisations, commissioners, policy makers, regulators, healthcare professionals, organisational functions)- Evidence as a mechanism for patients and the public to drive change (e.g. to shape efficiency calculations & forecasts)- Patient satisfaction surveys |

| Delivery: Optional patient led training | ||

| Considerations: Patient and public resourcing, support and the application of best practices | ||

| Recommendation: Integrate curriculum within existing infrastructure and institutions | ||

Asking questions triggers acquisition of literature to start the EBM cycle. The patient-acceptable interventions and patient-important outcomes should form the key components of the PICO (population, intervention, control and outcomes) question to define the knowledge need. This more holistic and shared vision provides a starting point to asking the right relevant questions. Acquisition of literature follows the question. Funding bodies for research seek applications with patient input and some panels include lay assessors. The framing of questions for EBM with patient input (above) is more likely to translate into literature searches that target the more patient-oriented research.

Appraisal of research looks at its validity and transferability in practice. To improve outcomes for patients, research must not only have integrity and be valid and reliable, it must incorporate their point of view as subject matter experts. Patient and public involvement in research is key to instilling science integrity.22 Journals frequently require adherence to GRIPP223 reporting criteria permitting examination of the extent to which patient perspective shaped the research. For example, as members of the independent steering committee patients can ensure that their ‘sense-checking’ offers complimentary safeguarding. The inclusion of patient involvement work into publications24 actively builds the evidence base in this field.

Application of findings is a challenge that requires change. Patients’ active involvement in the dissemination of research findings can be transformative for EBM. Their different networks,24 access and motivation compliments those of practitioners. They can cascade key research messages to strategic stakeholders, therefore, influencing decision-makers at all levels (e.g. commissioners, policy makers, and civil society organisations). But it can also democratise evidence disseminating results directly to health service users who are the potential beneficiaries of EBM. This could be especially powerful for influencing practitioners less engaged in EBM, and even those reticent to EBM.

Meeting training needs of practitioners and patientsThe focus has been on research and not on EBM. Increasing understanding of EBM is important to equip both practitioner and patients. Training will ensure that collaboration in EBM as a practitioner–patient joint venture will derive optimal value. Additionally, they should be taught together using the same curriculum to provide a consistent joint understanding for their diverse outlooks. Offering practitioner and patients an opportunity to nurture relationships at the earliest opportunity while mitigating power differentials should enable the added value all parties can contribute to be recognised.1,25 Embracing this commitment to open relationship building can ensure patients and practitioners become complimentary EBM enablers for each other providing a return on educational investment for the long term.

In addition, common integrated training solutions for practitioner and patients could help unlock entrenched attitudes towards each other. It could also help identify and support stakeholder knowledge requirements and encourage the adoption of more creative ways of learning. The BMJ's (British Medical Journal) educational series had patients choose topics and learning points from which doctors could earn continuing medical education credit.26 But training solutions are often focused on one stakeholder.10 This approach will reduce effectiveness of training for the involvement of service users in EBM. A joint multidisciplinary approach1 to the training of practitioners and patients in one setting could generate synergy to integrate training wants and needs.

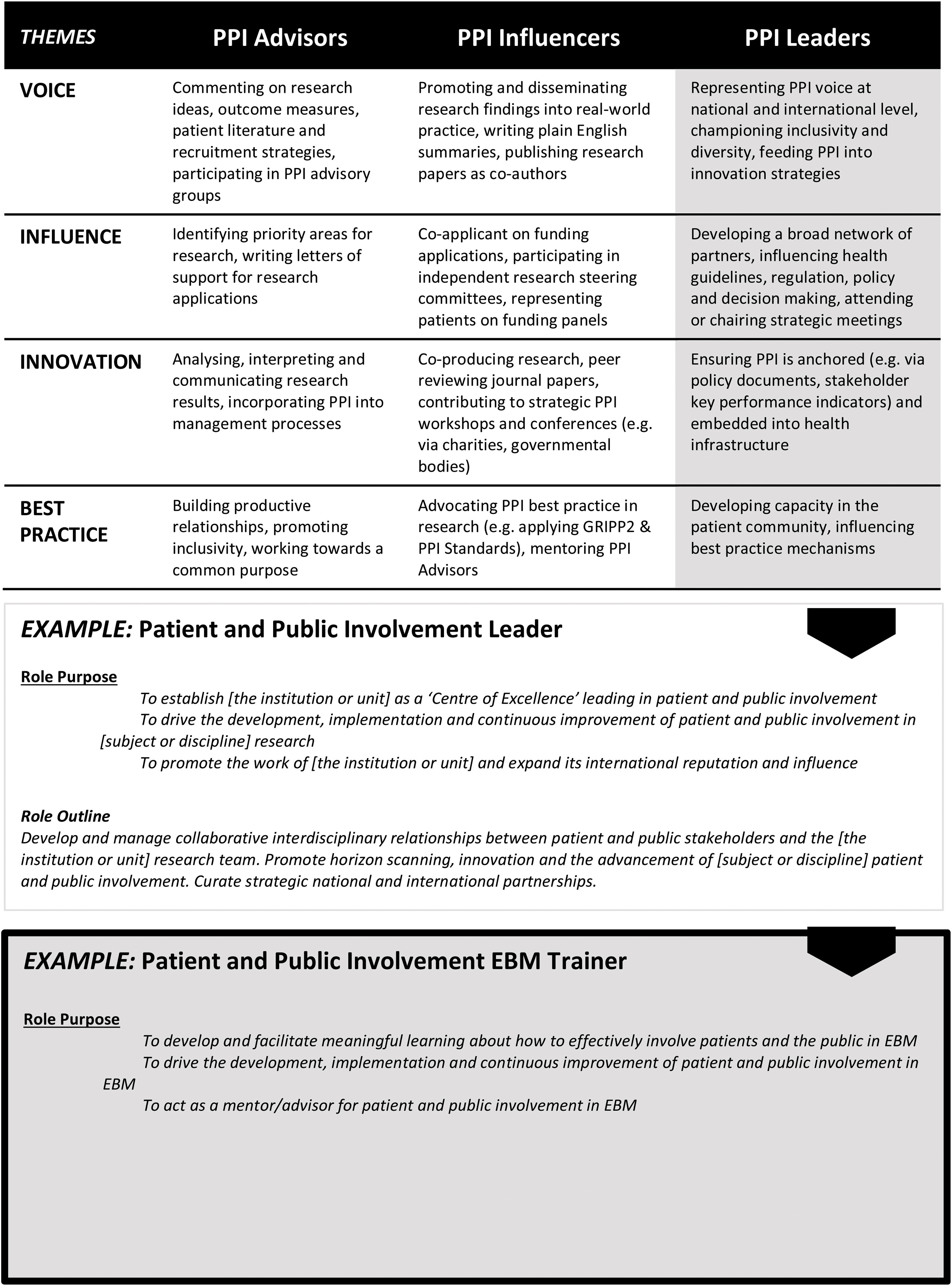

Fig. 2 outlines a spectrum of different roles patients can be involved with linked to their competencies, experience and interest. These broad capabilities highlight that teaching could be led by patients themselves to be interactive in a way that integrates their perspective into the practice of EBM. Developing active and inclusive patient involvement27 in this meaningful way (beyond their usual roles) can build skilled and motivated patient capacity able to communicate, bridge, shape and embed the EBM landscape. The qualitative course participant feedback showed that this was considered a new perspective of value with respect to empowering patients.

Influential stakeholders28 in the health care eco-system including practitioners will at some stage become patients or carers. Their involvement with EBM teaching in this capacity can ensure reciprocity as they leverage their influence to actively change practices, processes, systems, guidelines14,29 and infrastructure at all levels to reflect EBM. In turn, patient involvement will raise morale and aspiration while also improving health care effectiveness, productivity and patient outcomes. To not involve patients would be a missed opportunity. Any training must at its heart have improvement in patient care as its objective. Clinically integrated teaching and learning activities will provide the basis for the best educational practice.30–32

ConclusionImprovements in clinical research methodology and EBM have gone hand in hand. Emphasis on critical outcomes when deploying evidence must seek what is relevant for patients. Incorporating patient centred training and strategies in the EBM curriculum can inspire different ways of thinking and working with patients at the forefront. Their involvement in EBM courses, through attendance or teaching, can help deliver cognitive diversity and nurture long term mutually beneficial relationships. Patient and public involvement can translate into the design, conduct and relevant interpretation of research but, also help disseminate research findings through their networks to facilitate the transfer of research into practice. In this way practitioners can also find patients as integral EBM partners in real-world settings. To not involve patients comes with growing risks. EBM practitioner–patient joint ventures will require training to enable practitioners to effectively involve patients and the public in EBM and avoid its associated biases. Bold leadership is also needed to adopt a new approach and this will help ensure that EBM remains relevant and can be leveraged for maximum long term impact and patient benefit.

FundingThis research has not received specific support from public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that the manuscript was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Professor Khalid S. Khan is Distinguished Investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo (senior modality) grant given to the University of Granada by Spanish Ministry of Education.