This study aims to estimate the vaccination rate against herpes zoster (HZ) among public Primary Health Care (PHC) visitors eligible for vaccination based on the National guidelines. It also aims to explore the determinants associated with vaccination utilizing the health beliefs model (HBM).

Materials and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted between October and December 2022. The study took place in two public PHC units in the Heraklion prefecture, Crete, Greece. Eligible participants were visitors of the selected health units aged 60–75 years. The questionnaire elicited information on participants’ demographic data, health habits, and chronic illnesses. The HBM tool adapted for HZ vaccination was also used.

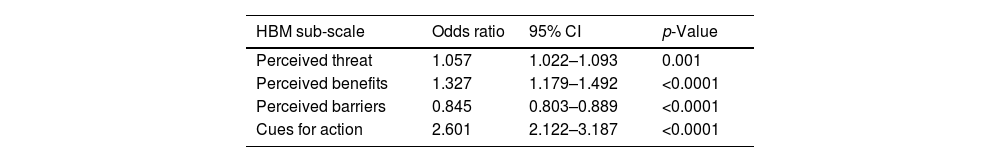

ResultsFour hundred primary care attendees participated in the study. Most participants were women (58.5%), with a mean age of 68.1 (±4.9) years. Fifteen percent of participants reported a history HZ illness, while 147 (36.8%) reported being vaccinated against HZ. Older age and respiratory illnesses were associated with higher rates of vaccination. Perceived threat (OR: 1.057; 95% CI 1.022–1.093; p=0.001), perceived vaccination benefits (OR: 1.327; 95% CI 1.179–1.492; p<0.0001), and motivation for action (OR: 2.601; 95% CI 2.122–3.187; p<0.0001) increased the odds of receiving HZ vaccination. Conversely, perceived barriers such as safety concerns were found to decrease the odds of HZ vaccination (OR: 0.845; 95% CI 0.803–0.889; p<0.0001).

ConclusionsThis study identified specific determinants positively associated with HZ vaccination, highlighting the need to enhance the education of healthcare professionals in personalized patient counseling.

Este estudio tiene como objetivo estimar la tasa de vacunación contra el herpes zoster (HZ) entre los visitantes públicos de atención primaria de salud elegibles para la vacunación según las directrices nacionales. También tiene como objetivo explorar los determinantes asociados con la vacunación utilizando el Modelo de Creencias en Salud (HBM).

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal entre octubre y diciembre de 2022. El estudio se llevó a cabo en dos unidades públicas de atención primaria de salud en la prefectura de Heraklion, Creta, Grecia. Los participantes elegibles fueron visitantes de las unidades de salud seleccionadas con edades entre 60 y 75años. El cuestionario obtuvo información sobre datos demográficos, hábitos de salud y enfermedades crónicas de los participantes. También se utilizó la herramienta HBM adaptada para la vacunación con HZ.

ResultadosEn el estudio participaron 400 asistentes de atención primaria. La mayoría de los participantes fueron mujeres (58,5%), con una edad media de 68,1 (±4,9) años. El 15% de los participantes informaron tener antecedentes de enfermedad por HZ, mientras que 147 (36,8%) informaron haber sido vacunados contra el HZ. La edad avanzada y las enfermedades respiratorias se asociaron con tasas más altas de vacunación. La amenaza percibida (OR: 1,057; IC95%: 1,022-1,093; p=0,001), los beneficios percibidos de la vacunación (OR: 1,327; IC95%: 1,179-1,492; p<0,0001) y la motivación para la acción (OR: 2,601; IC95%: 2,122-3,187; p<0,0001) aumentaron las probabilidades de recibir la vacuna HZ. Por el contrario, se encontró que las barreras percibidas, como las preocupaciones por la seguridad, disminuyen las probabilidades de la vacunación con HZ (OR: 0,845; IC95%: 0,803-0,889; p<0,0001).

ConclusionesEste estudio identificó determinantes específicos asociados positivamente con la vacunación contra HZ, destacando la necesidad de mejorar la educación de los profesionales de la salud en el asesoramiento personalizado al paciente.

Herpes zoster (HZ), commonly known as shingles, is a disease caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus (VZV).1 A characteristic feature of HZ is the presence of a unilateral, self-limited dermatomal rash.2 Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) which is characterized by persistent pain even after many months is a common complication of herpes zoster, significantly impacting the quality of life for patients. Elderly patients are at an increased risk of developing postherpetic neuralgia.2–4 Although HZ is rarely fatal (mortality rate 0.28–0.69cases/million population),5 it poses a global burden on public health as 20–30% of people are expected to develop HZ during their lifetime.6 A recent systematic review estimated the incidence rate of HZ as 5.23–10.9cases/1000 person-years of observation in Europe.7 The overall incidence of HZ in individuals aged 50 and above was calculated as 6.4cases/1000 person-years of observation, while for the age group 70–74 years, it was 15.94 cases/1000 person-years of observation.8 Several risk factors associated with an increased risk of developing HZ have been identified in the literature. These include a family history of infection, older age, female gender and immunosuppression.9 Chronic diseases that have been associated with an increased risk of HZ, include rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and depression.10

Vaccination coverage against herpes zosterCurrently, two types of vaccines against herpes zoster virus (HZV) are available worldwide. One is the live attenuated vaccine, and the other more recently is the recombinant one. Although the first vaccine against HZ received approval in 2006,11 it has not been incorporated into the vaccination programs of all European countries.12 In some countries despite the recommendation for vaccination, vaccines are not reimbursed by the National Health System. Therefore, complete data regarding vaccination coverage across countries are not available. A study in the United States estimated the vaccination coverage against HZ in individuals aged ≥60 years at 31.8% in 2014.13 A subsequent report showed a slight increase in vaccination coverage against HZ in 2017 (34.5%).13 In Australia, an analysis demonstrated that 46.9% of the population aged 70–79 years had been vaccinated against HZ.14 In the United Kingdom, a report estimated vaccination frequency at 21.4% in 70-year-olds and reached a surprisingly 80.2% in 78-year-olds.15 As regards Greece where the live attenuated vaccine reimbursed by the National Health System, a recent cross-sectional analysis reported that the vaccination frequency against HZ in individuals aged >60 years was 20%.16 Yet another report conducted in Heraklion, Crete, involving patients aged 60 and above with type 2 diabetes, calculated their vaccination coverage against HZ at 26.3%.17

Barriers and facilitators for vaccinationThe intention for vaccination among the elderly has been explored in various contexts, including vaccination against seasonal flu, pneumonia, herpes zoster, and COVID-19. The literature suggests that there are common demographic factors influencing vaccination intent, such as gender, marital status, low education levels, and racial minorities.18 Beyond demographic factors, specific beliefs and behaviors that act as barriers or incentives for vaccination in the elderly have been identified. These include self-protection, perceived severity, and perceived vulnerability to a disease.19 For example, in the context of COVID-19, the perceived severity of illness has been a significant motivator for vaccination among the elderly. Conversely, perceived mild severity of a disease, low likelihood of infection, and vaccine ineffectiveness act as barriers to vaccination.19,20 Other identified barriers to vaccination include inadequate information/awareness about both the disease and the available vaccines and a lack of trust in the vaccine production process.7 Finally, divergence observed in public discourse on COVID-19 vaccination indicates that supporters of certain political sides are less receptive to vaccination.21–23 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), vaccination hesitancy is defined as a delayed acceptance or refusal of vaccines and vaccination services despite their availability. Hesitancy towards vaccination and its impact on immunization programs are ranking as one of the top ten major issues for global health.24–26

On the other hand, vaccination facilitators include social norms and advice from friends and relatives that can serve as significant motivators for vaccine acceptance.18 External motivators for vaccination can range from a newspaper article to a television advertisement to social media campaigns.27 The recommendation of healthcare professionals is one of the main facilitators in the decision-making process for vaccination.18

Aims and objectives of the studyThis study aims to estimate the frequency of vaccination against herpes zoster (HZ) among visitors to Primary Health Care facilities and to explore factors that may be related to the administration of vaccination to those who are eligible. The study objectives are to answer the following research questions:

- 1.

What is the frequency of vaccination coverage against HZ among eligible visitors to Primary Health Care structures?

- 2.

What is the intention for vaccination against HZ in the corresponding population?

- 3.

Is there an association between demographic factors and vaccination coverage against HZ?

- 4.

Is there an association between chronic diseases/conditions and vaccination coverage against HZ?

- 5.

Are health beliefs related to vaccination against HZ?

A cross-sectional study was performed between October and December 2022. The setting included two public PHC units located in the Heraklion district, Crete, Greece. The first unit was located in the city of Heraklion serving the urban population of the district (≈180,000) and the other was located in a rural location of the district serving a population of ≈30,000 inhabitants. Participants were recruited during the working hours of the health care units. Data collection took place twice per week, at a consecutive manner.

Eligibility criteriaEligible participants were all visitors of the selected health care units aged 60–75 years. The age criterion was set according to the recommendation for shingles vaccination of the National Committee for Adult Vaccination of Greece. In Greece, recombinant vaccine is currently reimbursed for patients with specific immunosuppression morbidity. At the study period, the live attenuated vaccine was reimbursed for age specific general population group. Participants who visited the selected health care units for an urgent health reason, those who suffered from neurocognitive disorders (e.g. dementia) and other memory problems were not invited to participate.

Data collectionAll data were elicited via anonymous questionnaires which were collected by an investigator at the GPs office. The investigator was responsible for patient recruitment and replied to potential queries from participants. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the data that would be collected and were asked to participate upon providing informed consent.

DataThe questionnaire that was used collected information about the basic demographic characteristics of participants (gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, number and type of housemates), health habits (smoking, alcohol consumption, walking daily for >10min), basic somatometric characteristics (weight, height) and chronic illnesses encoded according in ICD-10 categories. Additionally, information about the vaccination status of participants and in particular about vaccination against shingles, annual vaccination against flu, pneumococcal vaccination, vaccination against COVID-19 and Tdap vaccination were recorded. Finally, the questionnaire included the Greek version of the health beliefs model (HBM)28 adjusted for herpes zoster vaccination.29 It comprises of 14 Likert scale items encoded as 1=completely disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, and 5=completely agree. From the HBM questionnaire four scales were constructed. The 1st scale namely “self-perceived threat” is comprised by the questions 1 up to 7 and has a score range 5–35. The 2nd scale namely “perceived benefits” is comprised by questions 8 and 9 and has a score range 2–10 units. The 3rd scale namely “perceived barriers” is comprised by questions 10 up to 14 and has a score range 5–25 units. Finally, the 4th scale namely “cues for action” is comprised by questions 15 up to 18 and has a score range 0–18 units.

Sample size estimationSample size was calculated on the basis of the estimated frequency of vaccination against HZ. It was assessed that a sample size of at least 382 individuals (with complete data) can provide a statistical power of 80% and a confidence level of 95% to measure the true value within ±4%, assuming that the true proportion of participants under investigation vaccinated against Hz is 20%.16 The above sample size was calculated to have 98.6% statistical power to estimate an effect size equal to 0.10 in a multiple regression model with six independent variables assuming a type-I error α=0.05.

Statistical analysisAll data were summarized using descriptive statistics. For categorical data, the number of responses and the corresponding percentage (n, %) per category were calculated, while for continuous variables, the mean values (standard deviations) were calculated. Univariate correlations were performed with the independent samples T-test statistic for continuous variables and with the use of Pearson's chi-square test for categorical variables. Since the scales of HBM were highly inter-correlated we performed four separate logistic regression models. Each model had as dependent variable the vaccination status against HZ (vaccinated vs. not vaccinated) and was adjusted for age, gender and level of education. The independent variables used were perceived threat (model 1), perceived benefits (model 2), perceived barriers (model 3) and cues for action (model 4). The level of statistical significance was set at p=0.05 and the statistical software used was IBM SPSS version 25.

ResultsGeneral demographic characteristics and health-related habits of the study populationFour hundred seventeen visitors from the selected PHC units were selected to participate in the study. Among them, 7/207 (3.4%) from the rural Health Center and 10/210 (4.8%) from the urban PHC unit denied participation. Finally, a total of 400 individuals participated, with 200 (50.0%) from each PHC unit.

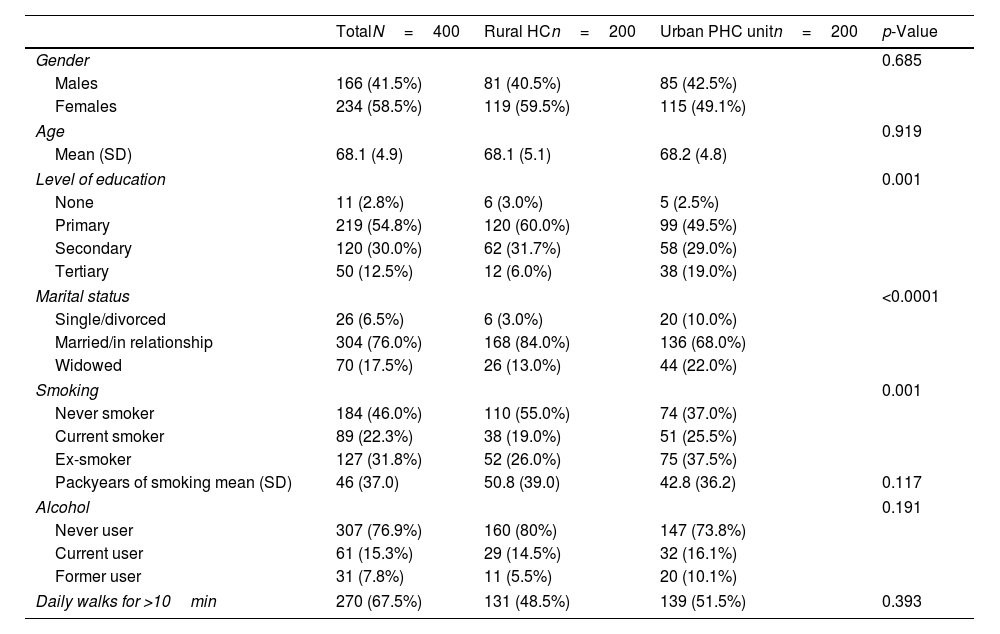

Basic demographic data are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 68.1 (±4.9) years and most of them (58.5%) were females. No significant differences were observed in gender and age distribution between the two PHC units (p>0.05). Most participants had received primary education (n=219, 54.8%), 120 (30.0%) secondary, 50 (12.5%) tertiary, and 11 (2.8%) had received no formal education. The education level was significantly higher among participants from the urban PHC unit compared to the rural Health Center. Most participants were married/in a relationship (n=304, 76.0%) while the percentage of participants who were single/divorced and widowed was higher among participants from urban PHC unit compared to the rural Health Center (p<0.0001). Forty-six percent of the participants reported never being smokers (n=184, 46.0%), 89 (22.3%) non-smokers, while 127 (31.8%) were former smokers, with the percentage of participants reporting former smoking being higher among participants from the rural Health Center (n=75, 37.5% vs. n=52, 26.0%). Regarding alcohol consumption, 61 (15.3%) participants reported current alcohol use, while n=31 (7.8%) were former alcohol users. Two out of three participants (n=270, 67.5%) reported daily walks for a duration of >10min.

General demographic characteristics and health-related habits of participants.

| TotalN=400 | Rural HCn=200 | Urban PHC unitn=200 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.685 | |||

| Males | 166 (41.5%) | 81 (40.5%) | 85 (42.5%) | |

| Females | 234 (58.5%) | 119 (59.5%) | 115 (49.1%) | |

| Age | 0.919 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 68.1 (4.9) | 68.1 (5.1) | 68.2 (4.8) | |

| Level of education | 0.001 | |||

| None | 11 (2.8%) | 6 (3.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | |

| Primary | 219 (54.8%) | 120 (60.0%) | 99 (49.5%) | |

| Secondary | 120 (30.0%) | 62 (31.7%) | 58 (29.0%) | |

| Tertiary | 50 (12.5%) | 12 (6.0%) | 38 (19.0%) | |

| Marital status | <0.0001 | |||

| Single/divorced | 26 (6.5%) | 6 (3.0%) | 20 (10.0%) | |

| Married/in relationship | 304 (76.0%) | 168 (84.0%) | 136 (68.0%) | |

| Widowed | 70 (17.5%) | 26 (13.0%) | 44 (22.0%) | |

| Smoking | 0.001 | |||

| Never smoker | 184 (46.0%) | 110 (55.0%) | 74 (37.0%) | |

| Current smoker | 89 (22.3%) | 38 (19.0%) | 51 (25.5%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 127 (31.8%) | 52 (26.0%) | 75 (37.5%) | |

| Packyears of smoking mean (SD) | 46 (37.0) | 50.8 (39.0) | 42.8 (36.2) | 0.117 |

| Alcohol | 0.191 | |||

| Never user | 307 (76.9%) | 160 (80%) | 147 (73.8%) | |

| Current user | 61 (15.3%) | 29 (14.5%) | 32 (16.1%) | |

| Former user | 31 (7.8%) | 11 (5.5%) | 20 (10.1%) | |

| Daily walks for >10min | 270 (67.5%) | 131 (48.5%) | 139 (51.5%) | 0.393 |

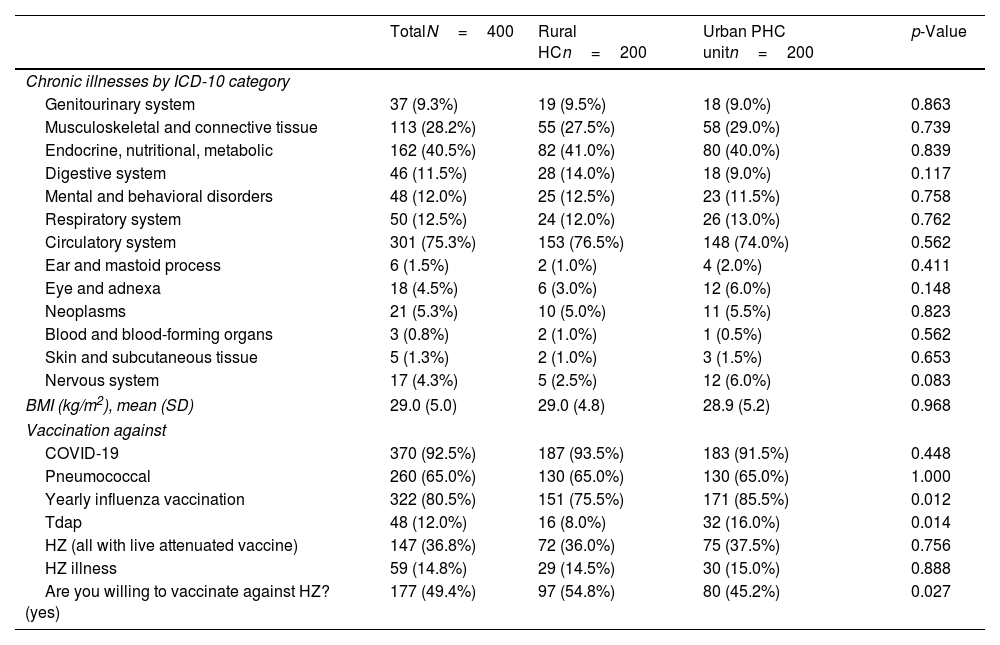

Among the most frequently diseases reported by the participants and categorized according to ICD-10 were those of the circulatory system (n=301, 75.3%), followed by endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (n=162, 40.5%), musculoskeletal and connective tissue ones (n=113, 28.2%), those of respiratory system (n=50, 12.5%), mental disorders and behavioral disorders (n=48, 12.0%), and diseases of the digestive system (n=46, 11.5%) (Table 2). No significant differences were observed in the frequency of chronic diseases between participants of the two PHC units (p>0.05 for all).

Chronic illnesses and vaccination status of participants.

| TotalN=400 | Rural HCn=200 | Urban PHC unitn=200 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic illnesses by ICD-10 category | ||||

| Genitourinary system | 37 (9.3%) | 19 (9.5%) | 18 (9.0%) | 0.863 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 113 (28.2%) | 55 (27.5%) | 58 (29.0%) | 0.739 |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 162 (40.5%) | 82 (41.0%) | 80 (40.0%) | 0.839 |

| Digestive system | 46 (11.5%) | 28 (14.0%) | 18 (9.0%) | 0.117 |

| Mental and behavioral disorders | 48 (12.0%) | 25 (12.5%) | 23 (11.5%) | 0.758 |

| Respiratory system | 50 (12.5%) | 24 (12.0%) | 26 (13.0%) | 0.762 |

| Circulatory system | 301 (75.3%) | 153 (76.5%) | 148 (74.0%) | 0.562 |

| Ear and mastoid process | 6 (1.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 4 (2.0%) | 0.411 |

| Eye and adnexa | 18 (4.5%) | 6 (3.0%) | 12 (6.0%) | 0.148 |

| Neoplasms | 21 (5.3%) | 10 (5.0%) | 11 (5.5%) | 0.823 |

| Blood and blood-forming organs | 3 (0.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 0.562 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | 5 (1.3%) | 2 (1.0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0.653 |

| Nervous system | 17 (4.3%) | 5 (2.5%) | 12 (6.0%) | 0.083 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 29.0 (5.0) | 29.0 (4.8) | 28.9 (5.2) | 0.968 |

| Vaccination against | ||||

| COVID-19 | 370 (92.5%) | 187 (93.5%) | 183 (91.5%) | 0.448 |

| Pneumococcal | 260 (65.0%) | 130 (65.0%) | 130 (65.0%) | 1.000 |

| Yearly influenza vaccination | 322 (80.5%) | 151 (75.5%) | 171 (85.5%) | 0.012 |

| Tdap | 48 (12.0%) | 16 (8.0%) | 32 (16.0%) | 0.014 |

| HZ (all with live attenuated vaccine) | 147 (36.8%) | 72 (36.0%) | 75 (37.5%) | 0.756 |

| HZ illness | 59 (14.8%) | 29 (14.5%) | 30 (15.0%) | 0.888 |

| Are you willing to vaccinate against HZ? (yes) | 177 (49.4%) | 97 (54.8%) | 80 (45.2%) | 0.027 |

Approximately 15% of the participants (n=59, 14.8%) reported having suffered from herpes zoster (HZ), while 147 (36.8%) participants stated that they have been vaccinated against HZ. The majority of participants (n=370, 92.5%) stated that they have been vaccinated against COVID-19, while two in three (n=260, 65.0%) were vaccinated against pneumococcus. No significant differences were observed in these rates between participants from the two PHC units (p>0.05 for all). Eight out of ten participants (n=322, 80.5%) reported receiving annual influenza vaccination, with the percentage being significantly higher among participants from the urban PHC unit compared to those from the rural Health Center (85.5% vs. 75.5%; p=0.012). Forty-eight participants (12.0%) reported being vaccinated against tetanus-diphtheria in the last decade, with this percentage being double among participants from the urban PHC unit compared to the rural Health Center (16.0% vs. 8.0%; p=0.014). The detailed data are presented in Table 2.

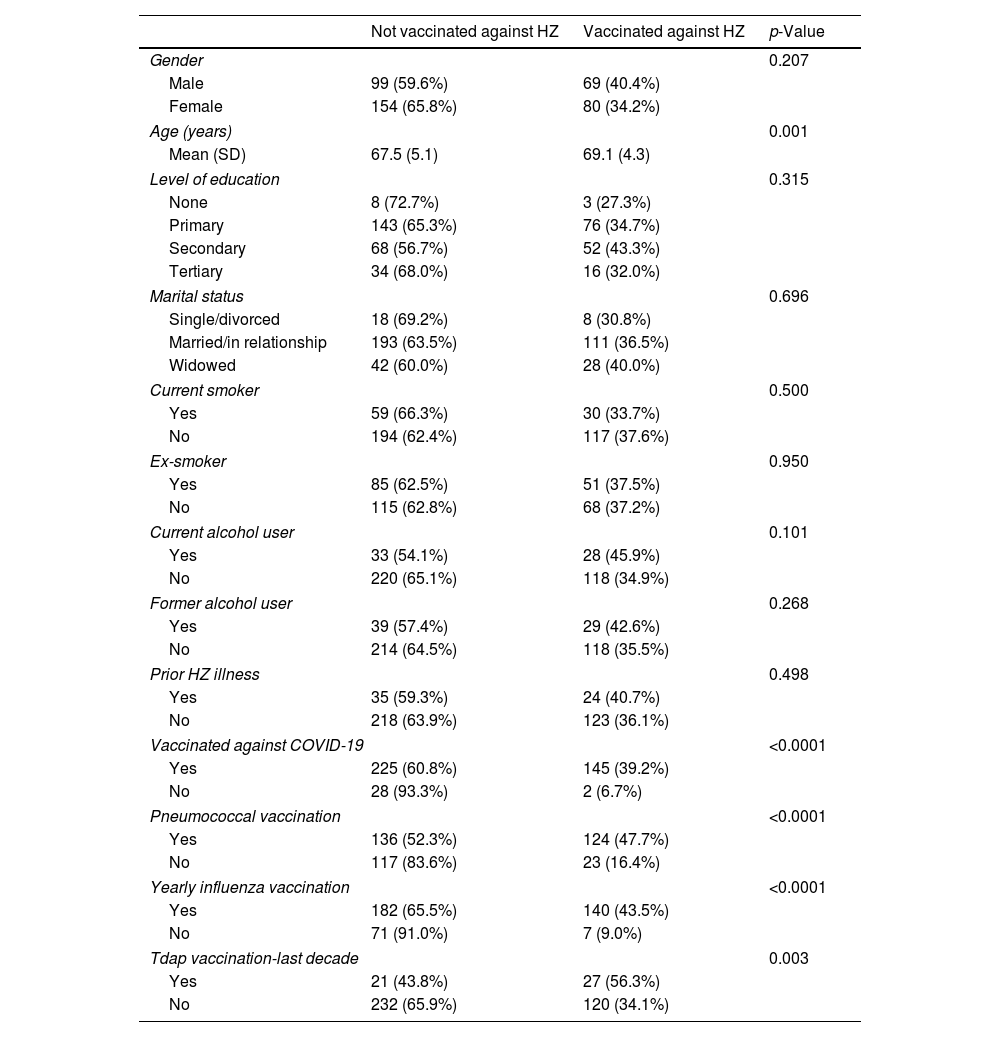

Univariate comparisons between vaccination status and selected characteristicsIn Table 3 the univariate comparisons between herpes zoster (HZ) vaccination status and demographic factors as well as participants’ health habits are presented. It is observed that the frequency of HZ vaccination was higher, though not statistically significant, among male participants compared to females (40.4% vs. 34.2%; p=0.207). The average age of participants who had been vaccinated against HZ was higher than those who had not been vaccinated (69.1±4.3 years vs. 67.5±5.1 years; p=0.001). No significant differences were identified between vaccination status and the level of education, marital status, smoking or alcohol use.

Univariate comparisons between vaccination status against HZ and basic demographic characteristics as well as other vaccinations.

| Not vaccinated against HZ | Vaccinated against HZ | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.207 | ||

| Male | 99 (59.6%) | 69 (40.4%) | |

| Female | 154 (65.8%) | 80 (34.2%) | |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 67.5 (5.1) | 69.1 (4.3) | |

| Level of education | 0.315 | ||

| None | 8 (72.7%) | 3 (27.3%) | |

| Primary | 143 (65.3%) | 76 (34.7%) | |

| Secondary | 68 (56.7%) | 52 (43.3%) | |

| Tertiary | 34 (68.0%) | 16 (32.0%) | |

| Marital status | 0.696 | ||

| Single/divorced | 18 (69.2%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| Married/in relationship | 193 (63.5%) | 111 (36.5%) | |

| Widowed | 42 (60.0%) | 28 (40.0%) | |

| Current smoker | 0.500 | ||

| Yes | 59 (66.3%) | 30 (33.7%) | |

| No | 194 (62.4%) | 117 (37.6%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 0.950 | ||

| Yes | 85 (62.5%) | 51 (37.5%) | |

| No | 115 (62.8%) | 68 (37.2%) | |

| Current alcohol user | 0.101 | ||

| Yes | 33 (54.1%) | 28 (45.9%) | |

| No | 220 (65.1%) | 118 (34.9%) | |

| Former alcohol user | 0.268 | ||

| Yes | 39 (57.4%) | 29 (42.6%) | |

| No | 214 (64.5%) | 118 (35.5%) | |

| Prior HZ illness | 0.498 | ||

| Yes | 35 (59.3%) | 24 (40.7%) | |

| No | 218 (63.9%) | 123 (36.1%) | |

| Vaccinated against COVID-19 | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 225 (60.8%) | 145 (39.2%) | |

| No | 28 (93.3%) | 2 (6.7%) | |

| Pneumococcal vaccination | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 136 (52.3%) | 124 (47.7%) | |

| No | 117 (83.6%) | 23 (16.4%) | |

| Yearly influenza vaccination | <0.0001 | ||

| Yes | 182 (65.5%) | 140 (43.5%) | |

| No | 71 (91.0%) | 7 (9.0%) | |

| Tdap vaccination-last decade | 0.003 | ||

| Yes | 21 (43.8%) | 27 (56.3%) | |

| No | 232 (65.9%) | 120 (34.1%) | |

As regards other vaccinations, the frequency of HZ vaccination was significantly increased in those who had been vaccinated against COVID-19 (39.2% vs. 6.7%; p<0.0001), against pneumococcus (47.7% vs. 16.4%; p<0.0001) compared to those who had not. Furthermore, those who reported annual influenza vaccination were vaccinated against HZ at significantly increased rates of vaccination against HZ compared to those who did not receive annual influenza vaccination (43.5% vs. 9.0%; p<0.0001). Finally, the frequency of HZ vaccination in those who reported receiving the tetanus-diphtheria booster shot in the last decade was 56.3%, a percentage significantly higher than those who had not received the tetanus-diphtheria booster shot in the last decade (34.1%; p=0.003). The above findings are presented in detail in Table 3.

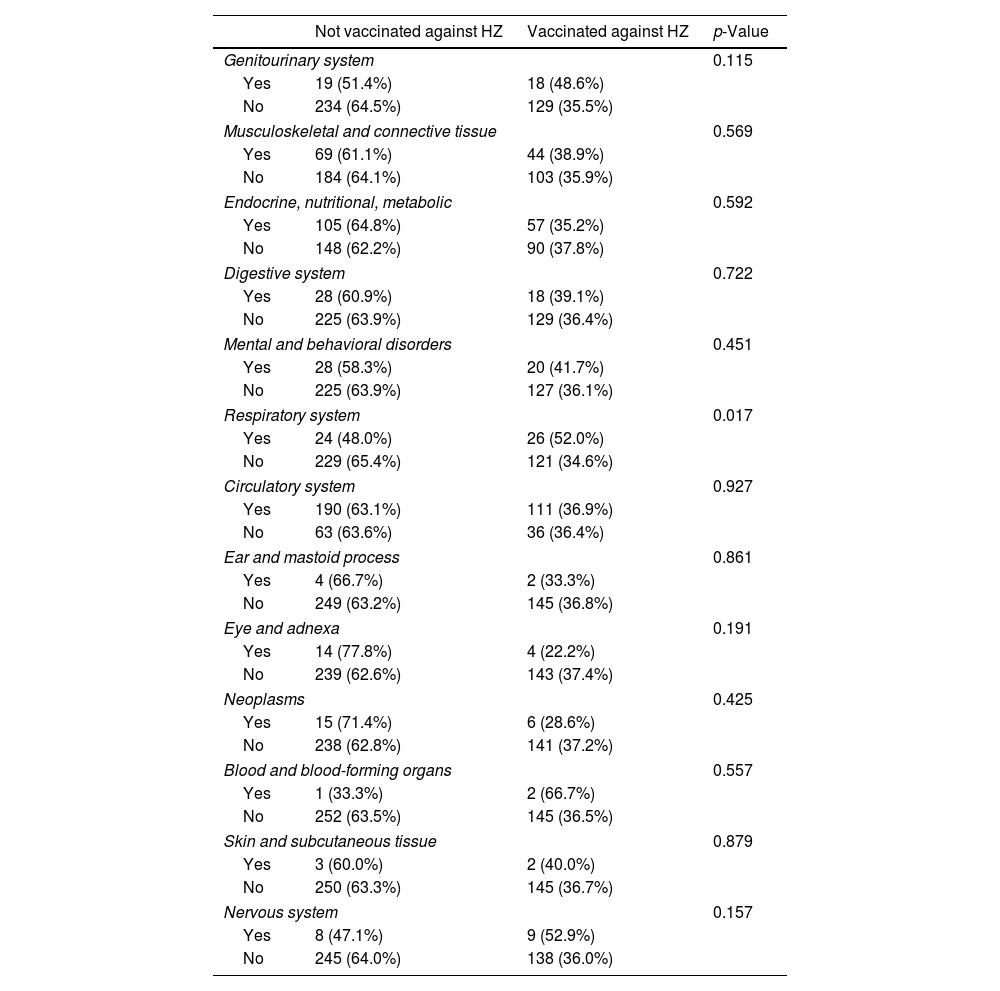

Table 4 provides a detailed analysis of the frequency of herpes zoster (HZ) vaccination among participants with and without chronic diseases. Participants with respiratory diseases were vaccinated at significantly higher rates compared to those without respiratory diseases (52.0% vs. 34.6%; p=0.017). No other significant differences between vaccination status against HZ and the presence of chronic illnesses was identified.

Univariate comparisons between HZ vaccination status and chronic conditions.

| Not vaccinated against HZ | Vaccinated against HZ | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genitourinary system | 0.115 | ||

| Yes | 19 (51.4%) | 18 (48.6%) | |

| No | 234 (64.5%) | 129 (35.5%) | |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue | 0.569 | ||

| Yes | 69 (61.1%) | 44 (38.9%) | |

| No | 184 (64.1%) | 103 (35.9%) | |

| Endocrine, nutritional, metabolic | 0.592 | ||

| Yes | 105 (64.8%) | 57 (35.2%) | |

| No | 148 (62.2%) | 90 (37.8%) | |

| Digestive system | 0.722 | ||

| Yes | 28 (60.9%) | 18 (39.1%) | |

| No | 225 (63.9%) | 129 (36.4%) | |

| Mental and behavioral disorders | 0.451 | ||

| Yes | 28 (58.3%) | 20 (41.7%) | |

| No | 225 (63.9%) | 127 (36.1%) | |

| Respiratory system | 0.017 | ||

| Yes | 24 (48.0%) | 26 (52.0%) | |

| No | 229 (65.4%) | 121 (34.6%) | |

| Circulatory system | 0.927 | ||

| Yes | 190 (63.1%) | 111 (36.9%) | |

| No | 63 (63.6%) | 36 (36.4%) | |

| Ear and mastoid process | 0.861 | ||

| Yes | 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | |

| No | 249 (63.2%) | 145 (36.8%) | |

| Eye and adnexa | 0.191 | ||

| Yes | 14 (77.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | |

| No | 239 (62.6%) | 143 (37.4%) | |

| Neoplasms | 0.425 | ||

| Yes | 15 (71.4%) | 6 (28.6%) | |

| No | 238 (62.8%) | 141 (37.2%) | |

| Blood and blood-forming organs | 0.557 | ||

| Yes | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | |

| No | 252 (63.5%) | 145 (36.5%) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0.879 | ||

| Yes | 3 (60.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | |

| No | 250 (63.3%) | 145 (36.7%) | |

| Nervous system | 0.157 | ||

| Yes | 8 (47.1%) | 9 (52.9%) | |

| No | 245 (64.0%) | 138 (36.0%) | |

The results from the multivariate logistic regression models predicting the odds of vaccination against HZ (yes/no) are presented in Table 5. It is observed that all four components were statistically significant predictors of vaccination against HZ. Specifically, the odds of vaccination were found to increase by 5.7% for each additional unit on the perceived threat scale (OR: 1.057; 95% CI 1.022–1.093; p=0.001) and by 32.7% for each additional unit on the perceived benefits of vaccination scale (OR: 1.327; 95% CI 1.179–1.492; p<0.0001). The cues for action were the most significant predictor of vaccination against HZ, as the odds of vaccination increased by 160% for each additional unit on the corresponding scale (OR: 2.601; 95% CI 2.122–3.187; p<0.0001). On the other hand, the scale of perceived barriers was associated with a decrease in the odds of vaccination against HZ (OR: 0.845; 95% CI 0.803–0.889; p<0.0001) (shown in Table 5).

Multiple logistic regression models predicting the odds of a patient being vaccinated against HZ (yes/no) with independent variable each one of the HBM subscales, adjusted for age, gender and level of education.

| HBM sub-scale | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived threat | 1.057 | 1.022–1.093 | 0.001 |

| Perceived benefits | 1.327 | 1.179–1.492 | <0.0001 |

| Perceived barriers | 0.845 | 0.803–0.889 | <0.0001 |

| Cues for action | 2.601 | 2.122–3.187 | <0.0001 |

The present cross-sectional study involved visitors to selected PHC structures aged 60–75 years for whom vaccination against HZ is recommended according to the National Adult Immunization Program. According to the results, a small proportion of them had suffered HZ. Although recommended, the vaccine was taken by only about 4 out of 10 participants. Most of them were sufficiently vaccinated against COVID-19, influenza and pneumococcus but very few against diphtheria-tetanus. Factors like older age, respiratory diseases and acceptance of vaccination against other diseases affected positively the vaccination rates against HZ.

Regarding the components of the HBM, all four components of the health belief model were significant predictors of vaccination against HZ. Perceived threat, perceived benefits and cues for action were found to increase the odds for vaccination against HZ while perceived barriers were identified to decrease the respective odds.

Vaccination ratesHe frequency of vaccination against herpes zoster in visitors to Primary Health Care structures aged 60–75 was found 36.8%. This is higher compared both to the rate estimated earlier in 2019 for individuals aged 60 and above in Greece (20.0%),16 and to the one calculated in patients with type 2 diabetes (26.3%) in a secondary outpatient clinic in Heraklion, Crete, in 2020.17 It is close though to the corresponding rate reported for the United States (34.5%), but remains lower compared to that from the United Kingdom (80.2% in individuals aged 78 and 40.6% in individuals aged 71) and Australia (46.9%).14,15,30 The observed increase in the vaccination frequency against HZ compared to that reported in studies from previous years in the same area may be attributed to the general awareness of vaccines and disease coverage, intensified recently by the COVID-19 pandemic and the vaccination campaign against it. Studies have indeed shown an increase in vaccination against seasonal influenza during the pandemic31 and characteristically a 355.8% increase in vaccination against pneumococcus during the pandemic has been reported in Taiwan.32 The role of the recent pandemic and the subsequent vaccination campaign is further confirmed by a recent systematic review, where the pandemic appears to have increased the intention to vaccinate against influenza regardless of gender, age, and occupation33 and no other factors such as gender or age or occupation seem to have contributed.

HZ vaccination determinantsOur findings regarding the determinants of vaccination against HZ exhibit several similarities compared to the corresponding findings in the literature. Specifically, a recent study from Italy revealed that vaccine acceptance against HZ increased with age.34 Concerning the importance of other vaccinations in performing vaccination against HZ, literature suggests that individuals with a generally positive attitude towards vaccination are more likely to have a positive attitude towards HZ vaccination,34 while influenza vaccination has been found to increase the intention to vaccinate against HZ.35 Regarding the components of the health belief model, the results of our study align completely with those in the literature, where significant correlations have been identified with all components of the model.29,35,36 Notably, doctor and healthcare professionals’ recommendations have been recognized as the strongest motivator for conducting and/or intending to vaccinate against HZ.34,35,37,38 Patients view them as a reliable information source regarding vaccines, and their guidance plays a crucial role in influencing patients’ choices to either undergo vaccination or abstain.39 Furthermore, the perception of vaccination benefits and the fear of consequences in case of illness increase the likelihood of vaccination,29,36 while fear of vaccine safety and effectiveness appeared to act as deterrent factors for HZ vaccination.

The finding that individuals suffering from chronic respiratory problems had a significantly higher vaccination rate against HZ compared to non-sufferers contradicts recent international research, where only one in three (33.1%) individuals suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had received the HZ vaccine despite 94% of participants being aware of it.40 In contrast, literature confirms that individuals with chronic respiratory diseases are more likely to be vaccinated against other diseases. Specifically, a recent study from the United States showed that individuals with chronic respiratory diseases and those with autoimmune diseases were more likely willed to be vaccinated against COVID-19.41 Another study from China indicated that the recent pandemic and vaccination against COVID-19 led to a significant increase in the frequency of influenza vaccination among those suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.40

Strengths and limitations of the studyThis study was a cross-sectional observational study conducted in two PHC units within the Heraklion prefecture of Crete, one in an urban setting and the other in a rural area. This fact gave us the opportunity to study and compare all the health aspects including vaccination rates between the population living in an urban center and the population living in and rural areas. The refusal rate for study participation was low (4.1%) leading to a more accurate description of the population visiting the selected primary care units. Another advantage of this study was the use of questionnaire, which allowed the collection of a variety of information such as demographic data, health habits, chronic diseases, vaccination coverage, and health beliefs. The above data were collected via personal interviews in the presence of the patients’ doctors providing the opportunity to resolve any questions. Additionally, the variety of collected data enabled us to investigate a plethora of associations between vaccination rates and several patient-related characteristics and draw useful conclusions and interpretations of individual behaviors and health beliefs.

The demographic characteristics and the frequency of chronic diseases were similar to comparable studies conducted in the same population of the Heraklion prefecture and other regions of Greece.42 However, the study did not include people that either visit private doctors, secondary/tertiary healthcare units, geriatric food units, or those who do not visit any healthcare facility. Data collection was done through interviews and completion of questionnaires in the presence of the treating physician and the researcher. This approach clarified any uncertainties that participants might have had. There is always though the possibility that the data may be prone to recall bias from the respondents. It should be noted that because the study took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the population might have been highly mobilized regarding vaccinations and could have influenced both coverage and the intention for vaccination, potentially impacting factors contributing to vaccination.

ConclusionsThis study estimated vaccination coverage against HZ to be higher compared to that estimated for individuals aged 60 and above in Greece before (2019) and, while it is still lower compared to other European countries. The age group eligible for vaccination against HZ is a diverse group. It consists of both healthy, working individuals and those with health issues who are retired. Thus, obstacles and motivations for vaccination may differ within this age group, requiring personalized approaches.

The significant association of vaccination against HZ and other vaccinations points to the direction of the existence of a vaccination “culture” among PHC visitors, yet the vaccination hesitancy is a timely issue which needs special attention. Recent studies have shown that misinformation circulating online is directly related to vaccination hesitancy. Results from this study point to the direction that proper education for healthcare professionals can increase the intention to vaccinate. General practitioners play a vital role in providing personalized counseling and behavior change to patients, and strengthening their education in these areas is essential. Within the context of the ongoing primary care reform in Greece, it is crucial to provide proper educational tools, training and incentives to general practitioners to enhance their role in strengthening the population's vaccination program, including vaccination against HZ.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMK and EKS mainly contributed to the study idea, hypothesis and design; MK collected and tabulated the data; AB carried out data analysis; MK and AB prepared a first draft; EKS and HD had substantially contributed to the study protocol design, data explanation, review and structural editing of the draft; GM performed literature search by adjusting text parts with creative edits; DK offered intellectual insights, critical comments and revised text parts of the manuscript, towards its progression. EKS supervised the study process. All authors edited and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical approvalThe study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the 7th Health Region of Greece (protocol number 44704/12-10-222 and approval ID: 48370). All data were encoded and stored in an anonymous database.

Informed consentWritten informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

FundingThis research received no external funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank Dr Theodore Vassilopoulos from the Health Center of Agia Varvara and Dr Foteini Anastasiou from the 4th Local Health Unit of Heraklion for their assistance in patient recruitment.