Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become a cornerstone treatment for patients with severe aortic stenosis, especially those unsuitable for surgery. Intravascular haemolysis has been described in patients with aortic stenosis. This study aimed to assess the prevalence of haemolysis in patients with severe AS undergoing TAVI and its association with immediate and 30-day post-procedural outcomes.

MethodsThe HEMO-TAVI study was a prospective, single-centre cohort study conducted at University Hospital Reina Sofía (Córdoba, Spain) from June 2020 to September 2023. Consecutive patients scheduled for TAVI were enrolled. Haemolysis was defined as LDH>220U/L plus ≥2 criteria (low haemoglobin, low haptoglobin, elevated reticulocytes, or schistocytes). The primary endpoint was a composite of peri-procedural and 30-day adverse events.

ResultsAmong 301 patients, pre-procedural haemolysis was identified in 18 (6.0%). Patients with haemolysis had higher interventricular septum thickness and transvalvular gradients. The composite endpoint occurred more frequently in the haemolysis group (44.4% vs 21.2%, ORadj 2.23, 95% CI 1.12–8.25, p=0.025). Haemolysis was independently associated with a greater number of complications (ORadj 3.26, 95% CI 1.19–8.47, p=0.016).

ConclusionPre-procedural haemolysis might be present in TAVI candidates and is associated with increased peri-procedural and 30-day complications. Pre-procedural haemolysis may serve as a marker of elevated procedural risk.

El implante valvular aórtico percutáneo (TAVI) se ha convertido en la piedra angular del tratamiento de los pacientes con estenosis aórtica (EA) severa, especialmente en aquellos que no son candidatos adecuados para el remplazo quirúrgico. Se ha descrito hemólisis intravascular en un número significativo de pacientes con EA. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la prevalencia de hemólisis en los pacientes con EA severa sometidos al TAVI, y su asociación con los resultados inmediatos y a los 30 días tras el procedimiento.

Material y métodosEl estudio HEMO-TAVI fue un estudio de cohortes prospectivo y unicéntrico realizado en el Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Córdoba, España) desde junio de 2020 hasta septiembre de 2023. Se incluyeron pacientes consecutivos programados para TAVI. La hemólisis se definió como LDH>220U/l más ≥2 criterios (hemoglobina baja, haptoglobina baja, reticulocitos elevados o esquistocitos). El objetivo primario fue una variable de resultado combinada de eventos adversos periprocedimiento y hasta los 30 días.

ResultadosDe 301 pacientes, se identificó hemólisis previa al procedimiento en 18 (6,0%). Los pacientes con hemólisis presentaban un mayor grosor del tabique interventricular y mayores gradientes transvalvulares. La variable de resultado combinada fue más frecuente en el grupo con hemólisis (44,4 frente al 21,2%, ORadj: 2,23; IC 95%: 1,12-8,25; p=0,025). La hemólisis se asoció de forma independiente con un mayor número de complicaciones (ORadj: 3,26; IC 95%: 1,19-8,47; p=0,016).

ConclusionesLos pacientes candidatos a TAVI pueden tener hemólisis subclínica y esta se asocia a un mayor número de complicaciones periprocedimiento y a los 30 días. La hemólisis puede servir por lo tanto como un marcador de riesgo de eventos adversos asociados a la intervención.

Transaortic valve implantation (TAVI) has extended care to many patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS). The 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart diseases recommend TAVI in older patients, in those who are high risk (STSPROM/EuroSCORE IIf>8%) or unsuitable for surgery.1 The prevalence of AS is remarkably high and is anticipated to increase further with population ageing.2 Accordingly, TAVI expenditure is expected to continue growing in the coming decades.3 Thus, an adequate selection of patients who are more likely to benefit from this procedure is key for optimizing clinical outcomes and ensuring a fair allocation of healthcare resources.

Anaemia is a common comorbidity in patients with AS and is associated with worse cardiovascular and bleeding outcomes. The causes of anaemia in this patient population are varied, and often overlap.4 Intravascular haemolysis is a relatively common finding in patients with AS and might or not lead to anaemia, remaining subclinical in a large percentage of cases. Although the precise mechanisms underlying haemolysis are not fully understood, its severity seems to be related to the valvular flow velocity across the aortic valve.5 Therefore, factors such as aortic valve area narrowing, altered blood flow dynamics, and shear stress are thought to play a central role in the development of haemolysis in severe AS patients.3,6

Subclinical haemolysis has been reported in 15–37% of patients after TAVI and seems to be associated with adverse outcomes.7,8 However, there is a lack of data on the prevalence of haemolysis in patients with severe AS before TAVI and its prognostic implications.

The main aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of haemolysis in patients with severe AS undergoing TAVI and its association with immediate and 30-day post-procedural clinical outcomes. Secondarily to examine the clinical, analytical and echocardiographic factors associated with haemolysis.

Material and methodsStudy design and settingHEMO-TAVI study is single-centre, observational and prospective cohort study carried out in University Hospital Reina Sofía (Córdoba Spain). Enrolment of the study participants occurred between June 2020 and September 2023. The general objective of HEMO-TAVI is to assess the impact of haemolysis in patients with AS undergoing TAVI. The aim of the present analysis is to describe the prevalence of pre-procedural haemolysis and to assess its association with peri-procedural and 30 days outcomes. The protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethic Committee of Córdoba (Spain) (reference code: 5049) and the study was conducted in accordance with institutional and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

ParticipantsWe enrolled consecutive patients with severe AS scheduled to undergo TAVI at our centre. The eligibility criteria are shown in table S1. Key exclusion criteria included: haematological disorders, other severe valvular heart disease associated with aortic stenosis, cardiac prosthesis wearer prior to TAVI implantation and aortic insufficiency without stenosis.

Variables, data sources and measurementsPre-procedural evaluation included a detailed medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram, laboratory tests, transthoracic echocardiography, and computed tomography angiography (CTA). Transthoracic echocardiography variables of interest were the size of the interventricular septum, the left ventricular ejection fraction, the estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure using tricuspid regurgitation, and the presence of aortic regurgitation or mitral regurgitation. The CTA variables of interest were aortic annulus diameter, perimeter and area; sinus-sinus, sinotubular joint and ascending aorta diameters; left and right coronary artery heights and right and left femoral artery diameters.

Pre-procedural haemolysis was defined as LDH>220U/L and the presence of ≥2 of the following criteria: haemoglobin<13.8g/dL (male) or <12.4g/dL (female), haptoglobin<50mg/dL, reticulocyte fraction ≥2%, schistocytes in peripheral blood present. The definition was adapted from the Skoularigis et al. criteria for haemolysis in mechanical heart valve prostheses, using the LDH threshold proposed by Horstkotte.9,10

Peri-procedural and 30-day events of interest included all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, cardiac tamponade, systemic embolism, vascular complications, severe aortic regurgitation, major bleeding, renal complications, pacemaker implantation and heart failure hospitalization. A composite endpoint was defined as the occurrence of any of these events.

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages), and continuous variables as median and interquartile range. For between-group comparisons, the chi-square test or the Fischer test were used to compare categorical variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Univariable and multivariable (adjusting for age and sex) logistic regression models were fitted to evaluate the association between IH and the combined endpoint. Additionally, univariable and multivariable (adjusting for age and sex) ordinal logistic regression models were used to evaluate the association between hemolysis and the number of events. Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

ResultsBaseline characteristicsFor the present study, 301 patients with severe AS scheduled to undergo TAVI were analyzed. The prevalence of pre-procedural haemolysis was 6%. The median age was 79.9 years (IQR: 75.8–84.5), and 49.2% of the patients were women. The clinical characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Regarding cardiovascular risk factors, arterial hypertension was present in 86.2% of patients, diabetes mellitus in 38.2%, dyslipidaemia in 63.4%, and obesity in 41.9%. Regarding other comorbidities, 7.6% of patients had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 26.2% had atrial fibrillation, and 23.6% had coronary artery disease, of which 22.3% had previously undergone percutaneous revascularization and 0.3% surgical revascularization. Additionally, 2.3% had peripheral arterial disease, and 55.1% had chronic kidney disease.

Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | Total (301) | No haemolysis (283) | Haemolysis (18) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 79.9 (75.8–84.5) | 79.9 (75.8–84.5) | 80.1 (73.8–85.8) | 0.941 |

| Female | 148 (49.2%) | 139 (49.1%) | 9 (50.0%) | 0.942 |

| BMI | 28.7 (25.9–31.7) | 28.9 (26–31.7) | 26.4 (23–31.5) | 0.110 |

| Hypertension | 259 (86.0%) | 244 (86.2%) | 15 (83.3%) | 0.725 |

| DM | 115 (38.2%) | 110 (38.9%) | 5 (27.8%) | 0.348 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 191 (63.4%) | 181 (63.9%) | 10 (55.5%) | 0.473 |

| COPD | 23 (7.6%) | 23 (8.1%) | 0 | 0.378 |

| AF | 79 (26.2%) | 74 (26.1%) | 5 (27.8%) | 0.999 |

| CAD | 71 (23.6%) | 65 (23.0%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.388 |

| PCI | 67 (22.3%) | 61 (21.5%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.249 |

| CABG | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 0 | 0.999 |

| PAD | 7 (2.3%) | 7 (2.5%) | 0 | 0.999 |

| Obesity | 126 (41.9%) | 120 (42.4%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.449 |

| CKD | 166 (55.1%) | 158 (55.8%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.338 |

| NYHA | 0.274 | |||

| I | 21 (7.0%) | 19 (6.7%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| II | 173 (57.5%) | 164 (57.9%) | 9 (50.0%) | |

| III | 94 (31.2%) | 89 (31.4%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| IV | 13 (4.3%) | 11 (3.9%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Surgical risk | 0.268 | |||

| Low | 3 (1.0%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0 | |

| Intermediate | 47 (15.6%) | 42 (14.8%) | 5 (27.8%) | |

| High | 230 (76.4%) | 219 (77.4%) | 11 (61.1%) | |

| Prohibitive | 19 (6.3%) | 17 (6.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | |

| Balloon-expandable valve | 69 (23%) | 65 (23%) | 4 (22.2%) | 0.999 |

| Treatment | ||||

| Aspirin | 263 (87.4%) | 249 (88.8%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0.206 |

| DOAC | 68 (22.6%) | 64 (22.6%) | 4 (22.2%) | 0.969 |

| VKA | 11 (3.6%) | 10 (3.5%) | 1 (5%) | 0.657 |

| Beta blocker | 126 (41.9%) | 118 (41.7%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.819 |

| RASI | 219 (72.7%) | 207 (73.1%) | 12 (66.7%) | 0.594 |

| Statin | 215 (71.4%) | 204 (72%) | 11 (61.1%) | 0.318 |

| Diuretic | 190 (63.2%) | 180 (63.6%) | 10 (55.5%) | 0.492 |

| Iron | 91 (30.2%) | 85 (30%) | 6 (33.3%) | 0.768 |

Median (IQR); n (%). BMI: body mass index, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AF: atrial fibrillation, CAD: coronary artery disease, PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG: coronary artery bypass graft surgery, PAD: peripheral artery disease, CKD: chronic kidney disease, DOAC: direct oral anticoagulant, VKA: vitamin K antagonist, RASI: renin–angiotensin system inhibitors

With respect to functional class according to the NYHA scale, 7.0% of patients were classified as NYHA I, 57.5% as NYHA II, 31.2% as NYHA III, and 4.3% as NYHA IV. Surgical risk was categorized as low in 1.0% of patients, intermediate in 15.6%, high in 76.4%, and prohibitive in 6.3%. The median haemoglobin value was 11.4 (9.7–12.0) g/dL in the Haemolysis group and 11.7 (10.5, 12.8)g/dL in the No Haemolysis group (p=0.162). Regarding treatment, 87.4% were taking aspirin, 22.6% direct oral anticoagulant, 3.6% vitamin K antagonist, 41.9% beta blockers, 72.7% renin–angiotensin system inhibitors, 7.14% statin, 63.2% diuretic and 30.2% iron. No significant differences were observed in baseline characteristics between the groups with and without haemolysis.

Comparison of CTA and echocardiographic parameters between the groupsCTA and echocardiogram values in the overall population and according to haemolysis groups are shown in Table 2. Haemolysis was not associated with any of the CTA variables. With respect to echocardiographic data, interventricular septum size and mean gradient were associated with haemolysis. More specifically, we found a larger interventricular septum size [13(12–15)mm vs. 16(13–17)mm, p 0.012] and a higher mean gradient [47(42–58)mmHg vs. 55(49–65), p 0.043] in patients with haemolysis. We found no difference in the other echocardiographic variables, including left ventricular ejection fraction, aortic valve area and aortic or mitral regurgitation.

Imaging test parameters.

| Characteristics | Total (301) | No haemolysis (283) | Haemolysis (18) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic CTA | ||||

| Ascending aorta (mm) | 35 (32–38) | 35 (32–38) | 35.2 (30.5–40.3) | 0.810 |

| Sinotubular joint (mm) | 28 (25–30) | 28 (25–30) | 27 (25–29.5) | 0.661 |

| Sinus-sinus (mm) | 32 (28.5–35) | 32 (28.8–35) | 32 (28.3–34.5) | 0.939 |

| Ring | ||||

| Maximum diameter (mm) | 26 (23–28) | 26 (23.2–28) | 26.5 (22.5–28.7) | 0.792 |

| Minimum diameter (mm) | 20 (19–22) | 20 (19–22) | 20 (18–21.7) | 0.409 |

| Mean diameter (mm) | 23 (21.5–25) | 23 (21.5–25) | 23.5 (20.4–24.9) | 0.926 |

| Area (mm2) | 413 (355–478) | 411 (355–479) | 426 (332–476) | 0.949 |

| Perimeter (mm) | 74 (68–79) | 74 (68–80) | 75 (66–79) | 0.920 |

| LCA height (mm) | 12 (10–14) | 12 (10–14) | 12 (11.3–12.9) | 0.657 |

| RCA height (mm) | 12 (11–15) | 13.1 (11–15) | 12 (11.8–15) | 0.661 |

| RFA diameter (mm) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) | 7.7 (7–9) | 0.684 |

| LFA diameter (mm) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) | 7.4 (6.9–8.2) | 0.40 |

| Echocardiogram | ||||

| IVS (mm) | 13 (12–15) | 13 (12–15) | 16 (13.17) | 0.012 |

| LVEF (%) | 64 (57–70) | 64 (57–70) | 62 (51–71) | 0.829 |

| PASP (mmHg) | 38 (30–47) | 38 (30–47) | 39 (31–50) | 0.898 |

| Aortic valve area (mm2) | 0.6 (0.46–0.8) | 0.6 (0.46–0.8) | 0.5 (0.45–0.66) | 0.308 |

| Maximum gradient (mmHg) | 80 (70–93) | 79 (70–93) | 91 (76–102) | 0.143 |

| Mean gradient (mmHg) | 47 (42–58) | 47 (42–58) | 55 (49–65) | 0.043 |

| Aortic regurgitation | ||||

| No | 152 (50.5%) | 143 (50.5%) | 9 (50%) | 0.870 |

| Mild | 101 (33.5%) | 95 (33.6%) | 6 (33.3%) | |

| Moderate | 43 (14.3%) | 40 (14.1%) | 3 (16.7%) | |

| Severe | 5 (1.7%) | 5 (1.8%) | 0 | |

| Mitral regurgitation | ||||

| No | 162(53.8%) | 155 (54.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | 0.148 |

| Mild | 111 (36.9%) | 101 (35.7%) | 10 (55.5%) | |

| Moderate | 22 (7.3%) | 21 (7.4%) | 1 (5.5%) | |

| Severe | 6 (2%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0 | |

Median (IQR); n (%). CTA: computed tomography angiography, LCA: left coronary artery, RCA: right coronary artery, RFA: right femoral artery, LFA: left femoral artery, IVS: interventricular septum, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, PSAP: pulmonary artery systolic pressure.

Analytical values in the overall population and according to haemolysis groups are shown in Table 3. We only found a higher LDH in the haemolysis group (189 vs. 261, p<0.001), with no differences in haemoglobin, mean corpuscular volume, red cell distribution width, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, bilirubin, ferritin or liver enzymes.

Analytical values.

| Analytical values | Total (301) | No haemolysis (283) | Haemolysis (18) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin | 11.60±1.59 | 11.64±1.58 | 10.90±1.68 | 0.162 |

| MCV | 91±8 | 91±8 | 94±5 | 0.160 |

| RDW | 15.29±2.22 | 15.30±2.25 | 14.96±1.68 | 0.890 |

| Creatinine | 1.01±0.47 | 1.02±0.48 | 0.90±0.25 | 0.405 |

| eGFR | 78±30 | 78±30 | 76±20 | 0.997 |

| LDH | 193±55 | 189±53 | 261±34 | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin | 0.64±0.57 | 0.64±0.58 | 0.62±0.24 | 0.481 |

| Ferritin | 90±105 | 89±107 | 107±83 | 0.125 |

| AST | 22±21 | 22±21 | 24±11 | 0.088 |

| ALT | 17±14 | 17±14 | 20±15 | 0.250 |

Mean±SD. MCV: mean corpuscular volume, RDW: red cell distribution width, Egfr: estimated glomerular filtration rate, LDH: lactate dehydrogenase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase.

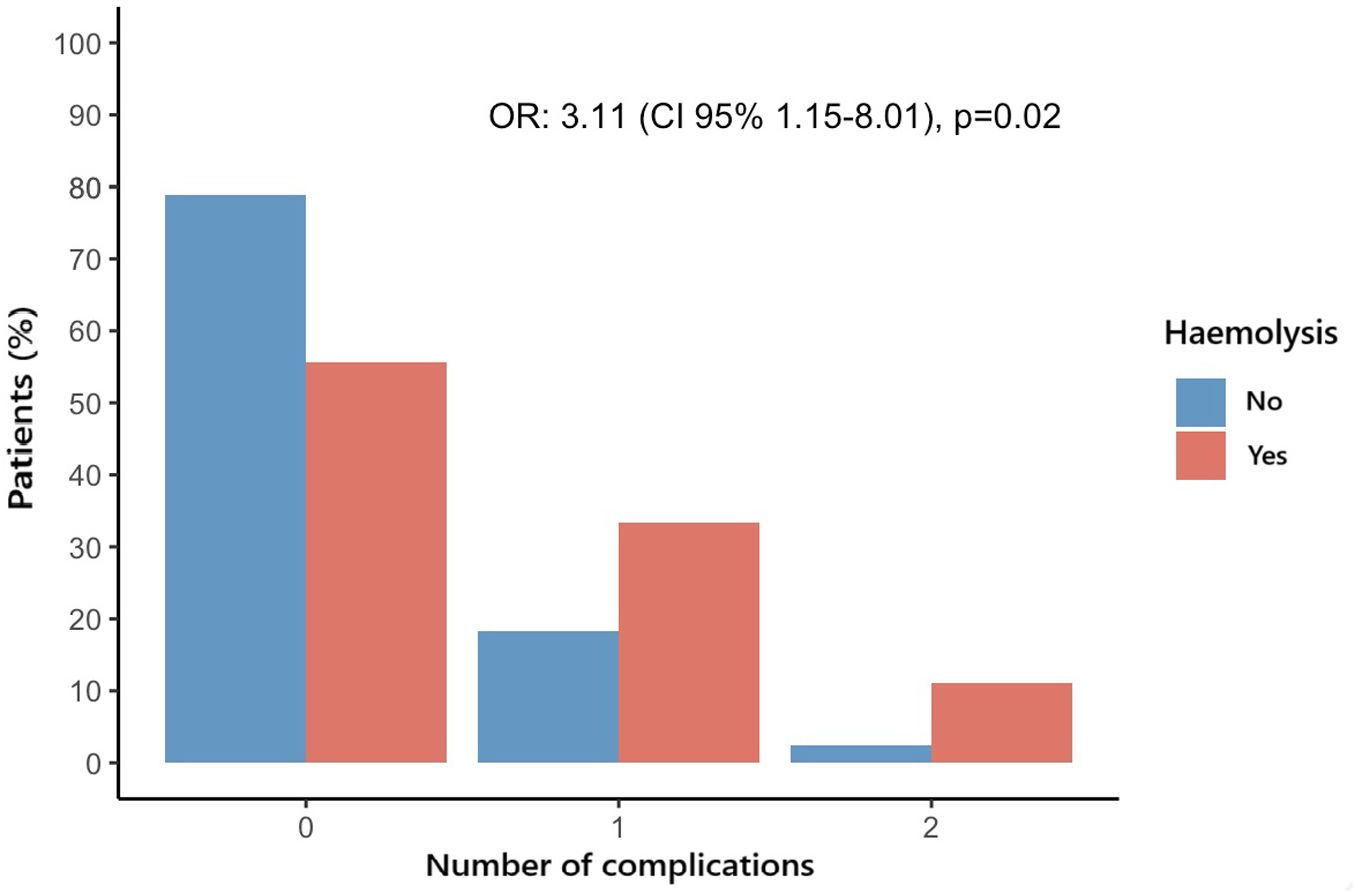

Overall, 68 (22.6%) patients experienced at least one adverse event of interest during the hospitalization or first 30-days after the procedure: 8 (44.4%) in the Haemolysis group and 60 (21.2%) in the No Haemolysis group (OR 2.97, CI 95% 1.09–7.87, p=0.028). After adjusting by age and sex, haemolysis continued to be associated with a higher risk for the combined endpoint (OR 2.23, CI 95% 1.12–8.25, p=0.025). The most frequent event was pacemaker implantation (14.3%). The distribution of the number of events according to the presence of haemolysis is shown in Fig. 1. The odds for having a higher number of complications were higher in patients with haemolysis (OR 3.11, CI 95% 1.15–8.01, p 0.020]. The association remained significant after adjusting by age and sex (ORadj 3.26 (CI 95% 1.19–8.47), p 0.016). When comparing each individual event between the group with and without haemolysis, we found a higher incidence of cardiac tamponade (1.1% vs 11.1%, p=0.030), without statistically significant differences in the rest of complications such as all-cause mortality, pacemaker implantation or heart failure hospitalization (Table 4).

Clinical outcomes.

| Complications at 30 days | Total (301) | No haemolysis (283) | Haemolysis (18) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined endpoint | 68 (22.6%) | 60 (21.2%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.037 |

| Mortality | 9 (3.0%) | 8 (2.8%) | 1 (5.5%) | 0.430 |

| AMI | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cardiac tamponade | 5 (1.7%) | 3 (1.1%) | 2 (11.1%) | 0.030 |

| Embolism | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| CVA | 6 (2.0%) | 6 (2.1%) | 0 | >0.999 |

| Vascular complication | 8 (2.6%) | 7 (2.5%) | 1 (5.5%) | 0.393 |

| Severe AR | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Major bleeding | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (5.5%) | 0.116 |

| Renal complication | 4 (1.3%) | 3 (1.1%) | 1 (5.5%) | 0.220 |

| Pacemaker | 43 (14.3%) | 39 (13.8%) | 4 (22.2%) | 0.303 |

| Heart failure | 2 (0.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | 0 | >0.999 |

n (%). AMI: acute myocardial infarction, CVA: cerebrovascular accident, AR: aortic regurgitation.

In this study, we analyzed a cohort of 301 patients with AS undergoing TAVI and identified a 6% prevalence of pre-procedural haemolysis. Patients meeting the criteria for haemolysis had a 2-fold higher risk of adverse peri-procedural and 30-day outcomes compared to those without haemolysis.

TAVI has extended care to many patients with severe AS and coexisting conditions which makes them not candidates for surgical aortic valve replacement, these candidates are usually elderly subjects with several co-morbid conditions, including the presence of anaemia in up to 50% of these subjects.11 In patients with AS moderate or severe anaemia was associated with significantly increased risk for aortic valve related death or heart failure hospitalization and also with significantly increased risk for major bleeding while under conservative management.4

DeLarochelierre et al.12 reported that the presence of anaemia and lower haemoglobin levels determined poorer functional status before and after the TAVI procedure which highlights the importance of implementing appropriate measures for the diagnosis and treatment of this frequent co-morbidity to improve both the accuracy of preprocedural evaluation and outcomes of TAVI candidates. Although little is known about the causes of anaemia in patients with aortic stenosis, the occurrence of recurrent haemorrhage or shear stress-dependent haemolysis have been reported in up to 25% of patients with severe AS.6

Haemolysis is a relatively common finding in patients with moderate to severe AS13 and the severity of intravascular haemolysis is related to valvular flow velocity of the aortic valve.5 According to Lafflame et al. patients with subclinical haemolysis experienced a mild decrease in haemoglobin levels at midterm follow-up, this could lead to a further decrease in haemoglobin in the long term, which could be related to a worse prognosis of these patients.7 This is in line with the results of our study showing worse outcomes in the first 30 days after valve implantation in patients who had subclinical haemolysis at baseline. Haemolysis could therefore be a marker of higher risk for TAVI. We hypothesize that this is driven by more advanced stages of severe AS, as indicated by the higher transvalvular gradients and greater interventricular septal thickness we observed in these patients. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that haemolysis results from increased shear stress across a narrowed valve, as previously suggested in the literature.13 In more advanced AS stages, patients are more likely to present for the procedure in poorer overall condition and functional status.14 Notably, the absence of significant differences in other clinical or imaging characteristics between the Haemolysis and No Haemolysis group suggests that the observed associations are unlikely to be confounded by pre-existing differences in patient profiles. This reinforces the potential role of haemolysis as an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes following TAVI, which might be considered during the decision-making process for this procedure.

This study is subject to limitations inherent to its single-centre, observational design, which may limit the generalizability of findings. Additionally, the small number of patients with haemolysis may reduce the statistical power to detect differences in specific outcomes. Further multicentre studies with larger cohorts are needed to validate these findings and to investigate if any intervention could ameliorate pre-procedural IH and if this intervention would improve prognosis.

ConclusionIn this cohort of patients with severe AS undergoing TAVI pre-procedural haemolysis was associated with a higher risk of adverse peri-procedural and 30-day outcomes. These results suggest that haemolysis might be a useful marker to identify a subset of patients at higher procedural risk. Larger studies are needed to validate our findings.

Ethical considerationsThe protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethic Committee of Córdoba (Spain) (reference code: 5049) and the study was conducted in accordance with institutional and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the procedure.

FundingThis project is funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation & Universities (Carlos III Health Institute, PI21/00949), and co-funded by the European Union, the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC/FEC-INV-CLI 21/031) and the Andalusian Society of Cardiology (Sociedad Andaluza de Cardiología Proyecto de Investigación unicéntrico – 2021). Dr. Gonzalez-Manzanares was awarded research contracts (CM22/00259, JR24/00064) and an international mobility grant (MV24/00106) by the Carlos III Health Institute (Madrid, Spain).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.