Cirrhosis represents the end-stage of chronic liver diseases. The ANSWER trial showed that long-term albumin (LTA) administration along with the standard medical treatment (SMT) improves survival and reduces complications in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites. The present analysis compared the potential annual cost of treatment with LTA+SMT, following the ANSWER regimen, with respect to SMT alone in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites from the Spanish healthcare system perspective.

MethodsCost of illness for patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites, treated with SMT alone or LTA+SMT (ANSWER regimen), was estimated. The annual incidence of complications and treatment frequency were collected based on the findings from the ANSWER trial. Unit costs were obtained from published data and transformed to 2019 Euros. The incremental cost was the difference in annual cost per patient between LTA+SMT and SMT alone treatment groups. A univariate sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure the robustness of the analysis.

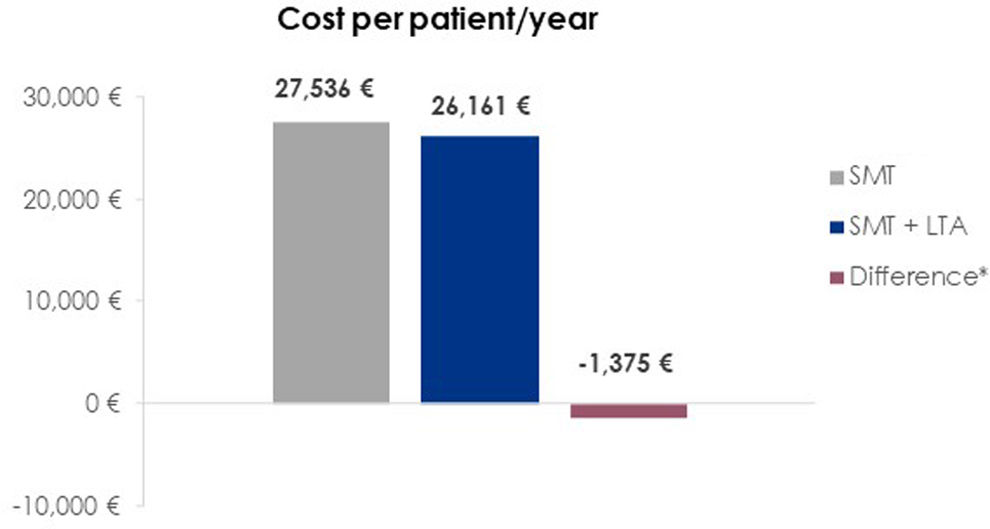

ResultsThe annual cost per patient of treatment and management of complications was estimated at €26,161 for patients treated with LTA+SMT, compared to €27,536 for those treated with SMT alone, representing saving costs of €1,375 per patient and year.

ConclusionsBy translating the ANSWER trial results to the Spanish clinical setting, LTA+SMT could reduce the healthcare cost associated with the management of cirrhotic patients with uncomplicated ascites due to the reduction of costly complications, which counterbalance the cost of LTA.

La cirrosis representa la fase terminal de las enfermedades hepáticas crónicas. En el ensayo clínico ANSWER se demostró que la administración prolongada de albúmina (LTA), en combinación con el tratamiento médico estándar (SMT), mejora la supervivencia y reduce las complicaciones en pacientes con cirrosis descompensada y ascitis no complicada. En el presente análisis se comparó el coste anual potencial del tratamiento con LTA+SMT (pauta ANSWER) con el SMT, desde la perspectiva del sistema sanitario español.

MétodosSe estimó el coste de la enfermedad en pacientes con cirrosis y ascitis no complicada tratados con SMT solo o con LTA+SMT (régimen ANSWER). La incidencia anual de complicaciones y la frecuencia de tratamientos se extrajeron de los resultados del ensayo ANSWER. Los costes unitarios se obtuvieron de fuentes publicadas y se ajustaron a euros del 2019. El coste incremental se definió como la diferencia en el coste anual por paciente entre los grupos de tratamiento. Se realizó un análisis de sensibilidad univariante para evaluar la robustez de los resultados.

ResultadosEl coste anual estimado por paciente para el tratamiento/manejo de complicaciones fue de 26.161 € en el grupo LTA+SMT y de 27.536 € en el grupo SMT, lo que representa un ahorro de 1.375 €/año por paciente a favor del grupo que recibió LTA.

ConclusionesLa aplicación de los resultados del ensayo ANSWER al contexto clínico español indica que la administración de LTA podría reducir los costes sanitarios asociados al manejo de pacientes con cirrosis descompensada y ascitis no complicada. Esta reducción se debe a la disminución de complicaciones costosas, lo que compensa el coste adicional de la albúmina.

Liver disease remains a major global health burden, contributing to over two million deaths annually (4% of all deaths worldwide). Currently, liver disease ranks as the 11th leading cause of mortality globally, though this figure may be underestimated due to underreporting. Regionally, cirrhosis has emerged as a significant cause of death, ranking 10th in Africa (up from 13th in 2015), ninth in both South-East Asia and Europe, and fifth in the Eastern Mediterranean.1 A wide range of factors can contribute to liver injury, including chronic viral infections, alcohol consumption, hereditary conditions, and autoimmune diseases. With sustained damage over time, fibrosis becomes widespread, impairing liver function and culminating in cirrhosis.2 Cirrhosis is divided into two phases: compensated and decompensated. Compensated cirrhosis is asymptomatic and presents a median survival of more than 12 years.3 The progression to decompensated cirrhosis (DC) is defined by the appearance of complications such as ascites, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic encephalopathy, and jaundice.4 DC is associated with poor prognosis, with median survival of 2 years.3

Treatment for DC relies on the management of each individual complication.5–7 Albumin, the most abundant protein in plasma, is essential for maintaining oncotic pressure, transporting endogenous and exogenous substances, and regulating inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial stabilization.5 The administration of human albumin is well proven and recommended to prevent renal dysfunction after large volume paracentesis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), and to treat acute kidney injury and hepatorenal syndrome (AKI-HRS).5,6,8

Long-term albumin (LTA) administration in patients with cirrhosis continues to be a matter of debate.9–11 Some studies have shown that this treatment not only enhances ascites management and prevents further cirrhosis decompensations, but also reduces hospital stay and improves survival.12–16 The ANSWER study was a non-profit, Italian, multicenter, open-label, pragmatic randomized controlled trial that enrolled 431 patients with non-complicated grade 2 and 3 ascites. These patients required a minimum dose of diuretics and were randomized to receive either standard medical treatment (SMT) alone or SMT plus LTA administration (40g of human albumin twice a week for the first two weeks, followed by 40g/week for up to 18 months). Overall, 18-month survival was significantly higher in the SMT+LTA group compared to the SMT group, corresponding to a 38% reduction in the mortality hazard ratio. Albumin administration also facilitated ascites management by significantly reducing the need for therapeutic paracentesis. Furthermore, the incidence of refractory ascites, diuretic-related side-effect (renal dysfunction, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia), SBP, non-SBP infections, HRS type 1, and severe hepatic encephalopathy were significantly lower in the SMT+LTA group. LTA decreased the need for albumin in established indications, such as prevention of paracentesis-induced circulatory dysfunction, renal dysfunction due to SBP, and the treatment of HRS. The additional expenses associated with the per-protocol administration of human albumin were significantly offset by cost savings resulting from reduced hospital admissions and fewer paracenteses in the SMT+LTA group. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated to be €21,265 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) – according to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), an ICER of €35,000 per QALY was considered the threshold for a treatment to be deemed cost-effective.12 Subsequently, economic evaluations adapted from the ANSWER trial have been conducted from the perspective of the healthcare systems in England, Mexico, and Brazil.17–19 These studies indicated that the addition of LTA to SMT in patients with DC and uncomplicated ascites could potentially result in cost reductions. Still, evidence appraising the economic impact of LTA in patients with DC remains scarce, and the clinical guidelines have highlighted the assessment of the long-term cost-effectiveness of albumin as a research priority.5,10

The aim of this study was to evaluate the economic impact of the LTA treatment regimen from the ANSWER study in patients with DC and uncomplicated ascites, considering the Spanish healthcare system perspective. We hypothesized that the extra cost of LTA administration might be compensated by a reduction in expensive complications, resulting in potential cost savings.

Materials and methodsThe present economic evaluation was designed to estimate the incremental cost of illness for patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites treated with SMT and albumin following the ANSWER trial treatment regimen (40g of albumin twice weekly for 2 weeks, and 40g weekly thereafter)12 compared to the cost of patients treated with SMT alone, over 12 months, and from the Spanish healthcare system perspective.

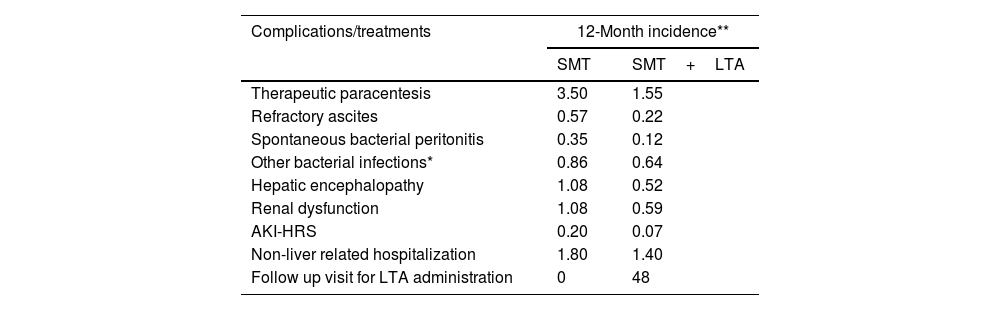

This analysis on the cost of illness relied entirely on consolidated data from existing publications, without involving human participants. The clinical and demographic parameters of the population incorporated in the economic assessment were assumed to correspond with those of the patients participating in the ANSWER trial.12 As this study was a secondary analysis based solely on aggregated data from the ANSWER trial and other published sources, no new subjects were recruited, and therefore no additional inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied beyond those defined in the original studies. Consequently, a sample size calculation was not required. The demographic and clinical characteristics used in the economic model reflect those reported in the ANSWER trial, which served as the primary clinical data source. The overall cost per patient and year considered the 12-month incidence of complications and frequency of treatments for patients undergoing treatment with SMT alone or SMT and LTA reported in the ANSWER trial (Table 1). The 12-month incidence of complications was provided by the authors of the ANSWER trial.

Annual incidence of complications and treatments per patient following SMT alone or SMT and LTA based on the ANSWER trial.12

| Complications/treatments | 12-Month incidence** | |

|---|---|---|

| SMT | SMT+LTA | |

| Therapeutic paracentesis | 3.50 | 1.55 |

| Refractory ascites | 0.57 | 0.22 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 0.35 | 0.12 |

| Other bacterial infections* | 0.86 | 0.64 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.08 | 0.52 |

| Renal dysfunction | 1.08 | 0.59 |

| AKI-HRS | 0.20 | 0.07 |

| Non-liver related hospitalization | 1.80 | 1.40 |

| Follow up visit for LTA administration | 0 | 48 |

AKI-HRS, Acute Kidney Injury Hepatorenal Syndrome; LTA, long-term albumin; SMT, standard medical treatment.

Unit costs for each complication, treatment obtained from public sources, and literature review were transformed to 2019 Euros (€). The unitary cost of each complication was multiplied by the incidence of the complication for the two arms. Similarly, the pharmacological treatment was estimated by multiplying the annual dosage of the diuretics administered (spironolactone/eplerenone and furosemide) by the cost per unit of dosage. For the treatment arm, and for albumin treatment, an additional cost per follow up visit due to albumin administration was also considered. Table 2 includes a detailed list of unit costs and sources. The pharmacological cost of human albumin considered the average cost/g of all Albutein® presentations marketed in Spain20 and the treatment regimen indicated in the ANSWER trial (a total of 48 infusions of 40g per patient and year).12 The pharmacological cost of SMT considered the average cost per unit of spironolactone (0.0021€/mg), eplerenone (0.0275€/mg), and furosemide (0.0018€/mg).

Unit costs of complications and treatments and data source.

| Unit cost(€, 2019) | Source | |

|---|---|---|

| Complications | ||

| Therapeutic paracentesis | 168€ | 21 |

| Refractory ascites | 5,735€ | 22,23 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 7,963€ | 22,23 |

| Other bacterial infections* | 4,024€ | 22–24 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 7,638€ | 21,25 |

| Renal dysfunction | 4,751€ | 22,23 |

| AKI-HRS | 7,806€ | 22,23 |

| Non-liver related hospitalization | 588€ | 21 |

| Treatment | ||

| Follow up visit for LTA administration | 150€ | 21 |

| Human albumin (cost/g) | 2.364€ | 20,26 |

| Diuretics (cost/mg) | ||

| Spironolactone | 0.0021€ | 20,26 |

| Eplerenone | 0.0275€ | 20,26 |

| Furosemide | 0.0018€ | 20,26 |

AKI-HRS, Acute Kidney Injury Hepatorenal Syndrome; LTA, long-term albumin.

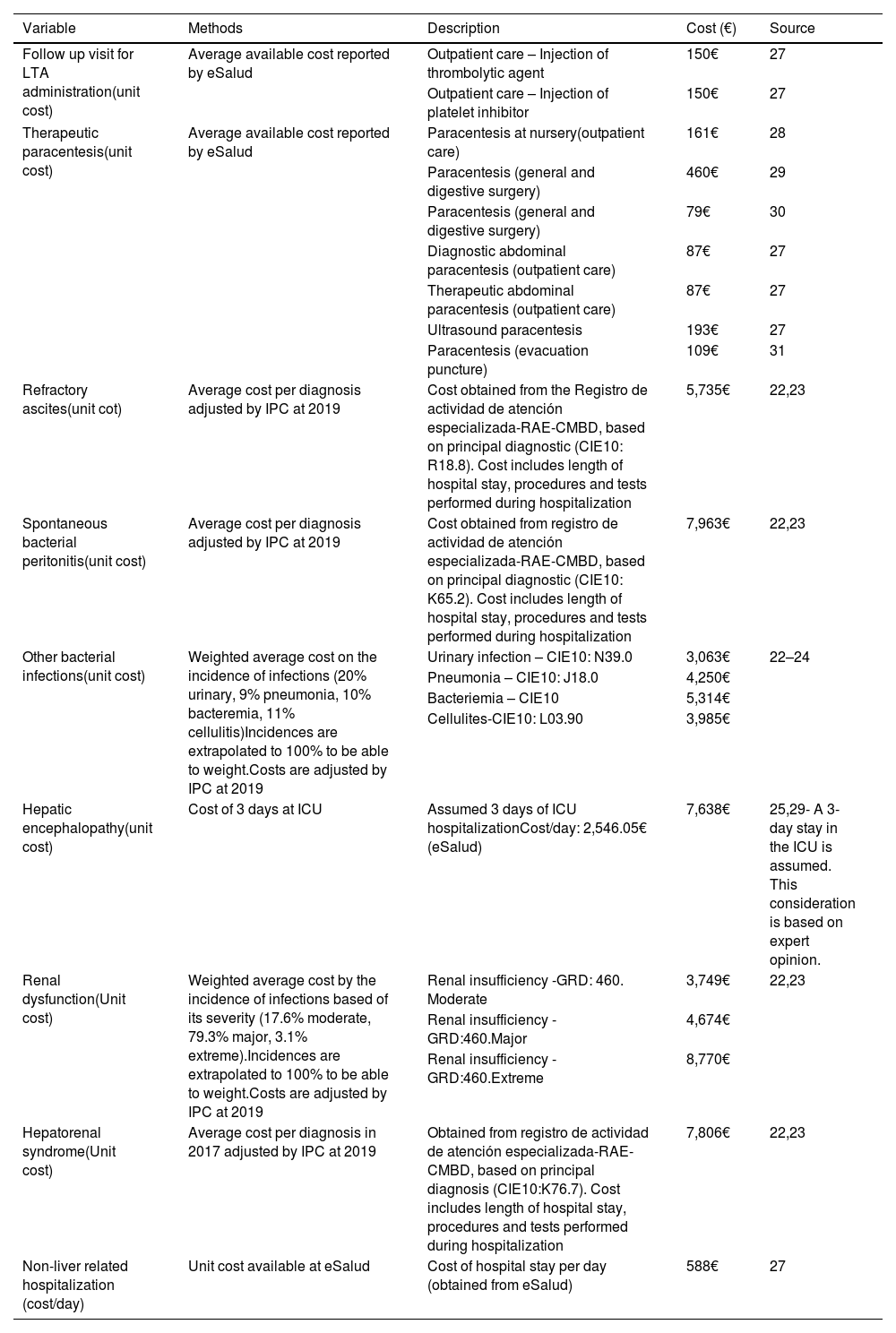

The incremental cost per patient treated with SMT and LTA, compared to SMT alone, was computed as the difference in annual cost per patient between the two treatment groups. A negative incremental cost indicates potential savings for the healthcare system when adding albumin to SMT vs SMT alone. No discount rate was applied. All costs and assumptions, detailed in Table 3, were validated by a physician with extensive experience in managing cirrhotic patients and in-depth knowledge in the healthcare system structure of Spain.

Assumptions for the calculation of the illness cost from the Spanish healthcare system perspective.

| Variable | Methods | Description | Cost (€) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up visit for LTA administration(unit cost) | Average available cost reported by eSalud | Outpatient care – Injection of thrombolytic agent | 150€ | 27 |

| Outpatient care – Injection of platelet inhibitor | 150€ | 27 | ||

| Therapeutic paracentesis(unit cost) | Average available cost reported by eSalud | Paracentesis at nursery(outpatient care) | 161€ | 28 |

| Paracentesis (general and digestive surgery) | 460€ | 29 | ||

| Paracentesis (general and digestive surgery) | 79€ | 30 | ||

| Diagnostic abdominal paracentesis (outpatient care) | 87€ | 27 | ||

| Therapeutic abdominal paracentesis (outpatient care) | 87€ | 27 | ||

| Ultrasound paracentesis | 193€ | 27 | ||

| Paracentesis (evacuation puncture) | 109€ | 31 | ||

| Refractory ascites(unit cot) | Average cost per diagnosis adjusted by IPC at 2019 | Cost obtained from the Registro de actividad de atención especializada-RAE-CMBD, based on principal diagnostic (CIE10: R18.8). Cost includes length of hospital stay, procedures and tests performed during hospitalization | 5,735€ | 22,23 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis(unit cost) | Average cost per diagnosis adjusted by IPC at 2019 | Cost obtained from registro de actividad de atención especializada-RAE-CMBD, based on principal diagnostic (CIE10: K65.2). Cost includes length of hospital stay, procedures and tests performed during hospitalization | 7,963€ | 22,23 |

| Other bacterial infections(unit cost) | Weighted average cost on the incidence of infections (20% urinary, 9% pneumonia, 10% bacteremia, 11% cellulitis)Incidences are extrapolated to 100% to be able to weight.Costs are adjusted by IPC at 2019 | Urinary infection – CIE10: N39.0 | 3,063€ | 22–24 |

| Pneumonia – CIE10: J18.0 | 4,250€ | |||

| Bacteriemia – CIE10 | 5,314€ | |||

| Cellulites-CIE10: L03.90 | 3,985€ | |||

| Hepatic encephalopathy(unit cost) | Cost of 3 days at ICU | Assumed 3 days of ICU hospitalizationCost/day: 2,546.05€ (eSalud) | 7,638€ | 25,29- A 3-day stay in the ICU is assumed. This consideration is based on expert opinion. |

| Renal dysfunction(Unit cost) | Weighted average cost by the incidence of infections based of its severity (17.6% moderate, 79.3% major, 3.1% extreme).Incidences are extrapolated to 100% to be able to weight.Costs are adjusted by IPC at 2019 | Renal insufficiency -GRD: 460. Moderate | 3,749€ | 22,23 |

| Renal insufficiency -GRD:460.Major | 4,674€ | |||

| Renal insufficiency -GRD:460.Extreme | 8,770€ | |||

| Hepatorenal syndrome(Unit cost) | Average cost per diagnosis in 2017 adjusted by IPC at 2019 | Obtained from registro de actividad de atención especializada-RAE-CMBD, based on principal diagnosis (CIE10:K76.7). Cost includes length of hospital stay, procedures and tests performed during hospitalization | 7,806€ | 22,23 |

| Non-liver related hospitalization (cost/day) | Unit cost available at eSalud | Cost of hospital stay per day (obtained from eSalud) | 588€ | 27 |

CIE, clasificación internacional de enfermedades; GRD, grupos relacionados al diagnóstico; ICU, intensive care unit; IPC, índice de precios de consumo; LTA, long-term albumin; RAE-CMBD, registro de actividad sanitaria especializada – conjunto mínimo básico de datos.

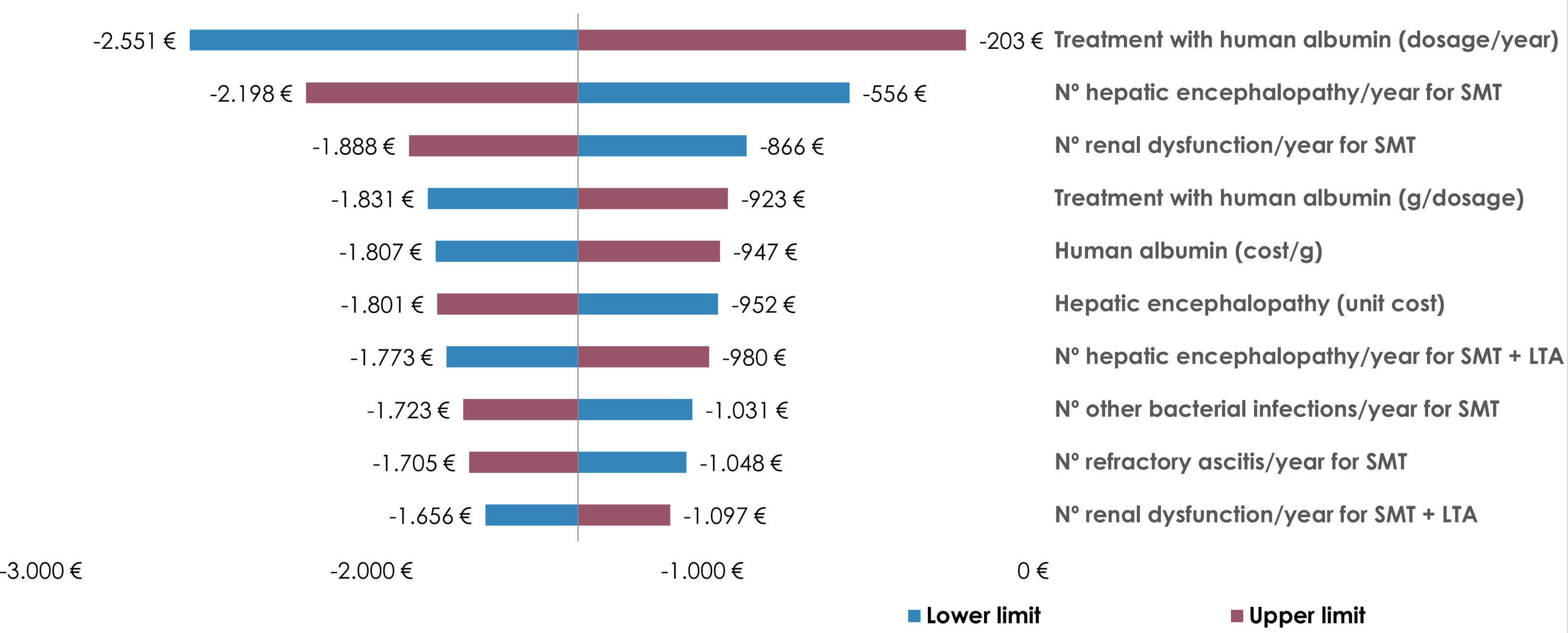

To ensure the robustness of our findings, a deterministic univariate sensitivity analysis was conducted. This analysis involved a 10% upward and downward adjustment of all variables considered in the economic model. The results of this sensitivity analysis, particularly focusing on the 10 variables that most significantly influenced the incremental cost per patient, were illustrated in a tornado diagram.

No statistical significance tests were conducted in this study, as the analysis was based on a deterministic economic model using aggregated data from published sources, rather than individual-level patient data. Therefore, hypothesis testing and p-values were not applicable.

ResultsThe overall annual cost per patient treated with SMT alone was estimated to be €27,536. In contrast, the combined use of SMT and LTA resulted in an annual cost of €26,161 per patient. This stands for a reduction of €1,375 per patient per year for the Spanish healthcare system when following the ANSWER study treatment regimen (SMT+LTA) (Fig. 1). The additional cost incurred from the human albumin pharmacological cost (€4,539), coupled with the follow-up visits required for LTA administration (€7,200), was offset by a reduction in the cost of complications (−€12,876). The primary contributors to this cost reduction were decreases in the expenses associated with hepatic encephalopathy (−€4,247), renal dysfunction (−€2,314), and refractory ascites (−€2,030) (Table 4).

Annual cost per patient treated with SMT alone or SMT and LTA.

| SMT | SMT+LTA | Incremental cost | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost of complications | 26,051€ | 13,175€ | −12,876€ |

| Therapeutic paracentesis | 588€ | 260€ | −328€ |

| Refractory ascites | 3,286€ | 1,256€ | −2,030€ |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 2,787€ | 948€ | −1,839€ |

| Other bacterial infections* | 3,460€ | 2,591€ | −869€ |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 8,211€ | 3,964€ | −4,247€ |

| Renal dysfunction | 5,108€ | 2,794€ | −2,314€ |

| AKI-HRS | 1,553€ | 539€ | −1,014€ |

| Non-liver related hospitalization | 1,058€ | 823€ | −235€ |

| Cost of pharmacological treatment | 1,485€ | 12,986€ | 11,501€ |

| Standard medical treatment | 1,097€ | 1,097€ | 0.00€ |

| Human albumin for acute use | 388€ | 150€ | −238€ |

| Human albumin for long-term use | 0€ | 4,539€ | 4,539€ |

| Follow-up visit for LTA administration | 0€ | 7,200€ | 7,200€ |

AKI-HRS, Acute Kidney Injury Hepatorenal Syndrome; LTA, long-term albumin; SMT, standard medical treatment.

The univariate sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess how changes in key variables would impact the incremental cost per patient. This analysis involved adjusting the variables by ±10% to simulate different scenarios. The results showed negative incremental costs across all scenarios, suggesting potential cost savings. The most influential variables on the incremental cost per patient were identified as the annual number of albumin infusions, the frequency of hepatic encephalopathy episodes, and the occurrence of renal dysfunction in patients receiving only SMT (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThis economic analysis focused on the long-term use of human albumin following the ANSWER treatment regimen for patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites in Spain. Our aim was to assess the economic impact of this therapeutic approach from the Spanish healthcare system perspective.

Our results indicate that LTA could lead to cost savings for the Spanish healthcare system (€1,375 per patient per year). These savings are primarily driven by reductions in costly complications associated with cirrhosis, such as hepatic encephalopathy (−€4,247), renal dysfunction (−€2,314), and refractory ascites (−€2,030). These findings suggest that the upfront cost of albumin (€4,539) and administration visits (€7,200) may be offset by the prevention of complications and associated healthcare utilization.

Our findings are consistent with previous economic evaluations based on the ANSWER results and conducted in other countries. Moctezuma et al. reported a potential annual cost reduction of 33,417 Mexican peso (MXN; approx. €1,693) per patient for the Mexican public healthcare system when LTA was added to SMT (costs reported in 2020 MXN).18 Similarly, Terra et al. reported that adding LTA to SMT could lead to costs savings of 118,759 Brazilian real (BRL; approx. €19,607) and BRL 189,675 (approx. €31,315) per patient annually for the public and private Brazilian healthcare systems, respectively (costs reported in 2021 BRL).19 Furthermore, a discrete event simulation model from the perspective of the English National Health Service (NHS) estimated potential annual cost savings of 264,589 pounds sterling (GBP; €315,041) when treating 30 patients (i.e., annual savings of GBP 8,820 [€10,502] per patient) with the addition of LTA to SMT (costs reported in 2020 GBP).17 While the magnitude of savings varies, likely due to differences in healthcare costs, treatment practices, and economic conditions, all studies consistently support the cost-saving potential of LTA in managing cirrhosis with ascites.

Our study, while comprehensive, is not devoid of limitations. First, clinical outcomes were directly extrapolated from the ANSWER trial conducted in Italy, which may not fully represent the Spanish population and/or routine clinical practice. Although the clinical outcomes used in our model were derived from the ANSWER trial, it is important to acknowledge that differences in healthcare systems, patient characteristics, and clinical practice between Italy and Spain may limit the direct applicability of these findings to the Spanish setting. Future studies based on real-world data from Spanish cohorts are warranted to validate and contextualize these results. Second, the analysis relied on aggregated data, limiting the ability to account for patient-level variability or perform subgroup analyses. Third, direct costs for patients or indirect costs such as loss of productivity or caregiver burden were not considered since the economic analysis was focused solely on direct healthcare costs from the perspective of the Spanish healthcare system. Finally, the model assumes full adherence to the treatment regimen, which may not always occur in real-world settings. Therefore, future research should explore real-world treatment patterns such as dosing, frequency, or duration, and effectiveness to confirm our findings. Liver cirrhosis is associated with high morbidity and mortality, with limited treatment options to reduce costly complications. Investigating long-term outcomes and cost-effectiveness, while considering different healthcare system perspectives, will be crucial for optimizing clinical practices and improving patient care.

From a clinical perspective, our findings suggest that incorporating LTA therapy into standard care for patients with cirrhosis and uncomplicated ascites could reduce the economic burden on the Spanish healthcare system by preventing costly complications. These results support the broader adoption of LTA in appropriate patients. Future research should focus on validating these findings using real-world data, exploring patient-reported outcomes, and conducting cost-effectiveness analyses that incorporate QALYs and societal costs.

ConclusionIn conclusion, translating the ANSWER trial results to the Spanish clinical setting, LTA in combination with SMT may reduce healthcare costs associated with the management of patients with DC and uncomplicated ascites. LTA reduced the overall burden of costly clinical decompensations, which counterbalance the cost of albumin therapy. Further studies are warranted to confirm these findings in real-world settings and to explore their broader applicability.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFernandez J contributed to the model validation and interpretation of results; Simo P, Davis A, Coll C and Fuster C contributed to the study conceptualization, data analysis and interpretation of results. Aceituno S and Soler M contributed to the study conceptualization and data analysis. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version and its submission to Medicina Clinica.

Ethical considerationsThis study is based on secondary analysis of previously published data and publicly available cost databases. No new data were collected from human participants, and no interventions were performed. Therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not required.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this publication, the authors did not use generative AI or AI-assisted technologies.

FundingThis study was funded by Grifols.

Conflict of interestCCO and CF are full-time employees of Grifols and have no other competing interests to declare.

CCO and CF declare having no other conflict of interest.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Dr. Paolo Caraceni and the authors of the ANSWER trial for providing 12-month rates of treatments, complications, and hospitalizations. Irene Mansilla, MSc and Eugenio Rosado, PhD (Grifols) are acknowledged for medical writing and editorial support in the preparation of this manuscript.