Artificial intelligence (AI) has revolutionized the way modern organizations operate, defining the transition from traditional industries to digital industries in which production systems can communicate, self-monitor, and collaborate autonomously. This study proposes a new framework for the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem that emphasizes the relationships, significance, and necessity of the factors shaping this field. Adopting a multifaceted approach that integrates several analyses—partial least squares structural equation modeling, importance-performance analysis, necessary conditions analysis, and artificial neural networks—this study identifies five predictors of AI entrepreneurship intention: entrepreneurial ecosystem, social influence, openness, performance expectancy, and market changes. Using 765 responses collected through a questionnaire from potential AI entrepreneurs, the findings show that the entrepreneurial ecosystem and social influence directly influence AI entrepreneurial intention, while the other factors act as mediators or moderators. The results indicate that managerial interventions should prioritize the entrepreneurial ecosystem and social influence, which are highly important but relatively underperforming. Moreover, although openness and performance expectancy are not primary drivers of AI entrepreneurial intention, they represent necessary conditions. This study makes an original contribution by examining the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the context of AI, as well as entrepreneurial intentions to adopt AI when starting a business.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into business operations is one of the many factors that impact entrepreneurial intention—the determination to launch a new business. Therefore, the field of business innovation and operational efficiency is evolving through the incorporation of AI in entrepreneurship. Moreover, AI technologies are shaping entrepreneurial intentions, improving conventional business models, and opening new opportunities. This shift toward AI adoption is particularly evident in digital entrepreneurship, where AI serves as a key enabler for both startups and established firms, offering significant opportunities for innovation and value creation (Bakri et al., 2024). Consequently, digital entrepreneurship is regarded as a distinct form of entrepreneurial activity driven by the rise of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and the broader phenomenon of digitalization (Romero-Castro et al., 2023; Upadhyay et al., 2022).

AI’s role in entrepreneurship can be understood through its contribution to competitive advantage. Bakri et al. (2024) find that startups leveraging AI technologies, adopting digital entrepreneurship practices, and fostering innovation readiness gain a competitive advantage that translates into higher revenue, lower costs, and improved operational efficiency. Lee et al. (2024a) show that AI startups enhance their competitiveness through the use of big data systems, the adoption of AI technologies, and digital transformation. Similarly, Lahamid et al. (2023) highlight that AI adoption can drive economic development, as organizations use these technologies to optimize operations and production activities, thereby strengthening competitiveness. Overall, the application of AI in business has emerged as a powerful driver in the global economy, supporting internationalization, enhancing firms’ ability to manage complex environments, and reshaping the dynamics of competition and market expansion (Moharrak et al., 2024).

However, despite these prospects, studies reveal tensions between the transformative potential of AI and entrepreneurs’ relatively slow or uneven adoption of it (Kim et al., 2024; Margaretha et al., 2025). While research such as Upadhyay et al. (2022) highlights the opportunities that AI offers for digital entrepreneurship, it lacks theoretical clarity on why certain ecosystem factors shape entrepreneurial intention toward AI adoption. This gap reflects an incomplete understanding of how entrepreneurial ecosystems evolve when disruptive technologies such as AI emerge.

Existing theories of entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam & Spigel, 2016), technology adoption (Davis, 1989), and behavioral theory (Ajzen, 1991) provide useful but partial explanations in this context. These frameworks typically conceptualize digital ecosystems in terms of infrastructure and networks, but they do not adequately account for the specific characteristics of AI or the intentions and behaviors of entrepreneurs. Therefore, this study introduces the concept of an “AI-based entrepreneurial ecosystem,” extending entrepreneurial ecosystem theory to explicitly incorporate AI-specific dimensions and thereby enhance analytical precision beyond existing models of digital or technological ecosystems.

This research also contributes to theory building by examining Romania as a theoretically significant context. Romania combines a fast-growing IT sector and digital infrastructure with relatively low levels of AI adoption among startups (Ionașcu, 2025). This juxtaposition creates a natural laboratory to examine how ecosystem conditions influence entrepreneurial intention in an environment characterized by high potential but uneven AI adoption. Findings from this context can challenge and enrich generalizable theories about how ecosystems shape entrepreneurial intention in the face of disruptive technologies. This study makes an incremental contribution to entrepreneurial ecosystem theory and technology-adoption models through a new conceptualization of an AI entrepreneurship ecosystem and the empirical identification of its dimensions that condition entrepreneurial intention toward AI adoption.

Specifically, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the components of the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem?

RQ2. How does the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem contribute to the growth of AI entrepreneurial intentions?

RQ3. What dimensions of the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem condition AI entrepreneurial intention?

To address these questions, a questionnaire was developed and administered to individuals with entrepreneurial intentions. The responses were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), importance-performance map analysis (IPMA), necessary condition analysis (NCA), and artificial neural networks (ANN) to identify the ecosystem dimensions that condition AI entrepreneurial intention. This study contributes to the literature by developing and empirically testing a multidimensional framework that integrates entrepreneurial ecosystem factors with individual-level enablers to explain AI entrepreneurial intention, offering theoretical insights and practical guidance for ecosystem stakeholders. In the following sections, the study concepts will be reviewed, the proposed hypotheses will be motivated, and the methodological framework and research results will be presented, followed by a discussion of the study results and final observations.

Theoretical background of artificial intelligence entrepreneurshipDynamic changes in entrepreneurship have positioned AI as a transformative force, reshaping traditional business models and creating opportunities for entrepreneurs to reconfigure value creation processes (Usman et al., 2024). However, these transformations are neither uniform nor universally positive. Previous studies (Dwivedi et al., 2021) show that although AI enables automation and data-driven decision-making, its impact on entrepreneurial activity depends on institutional support, ethical acceptability, and the entrepreneur’s absorptive capacity, resulting in mixed empirical findings across contexts.

Although the term AI appears relatively new in everyday language, its foundations date back to the 1950s and 1960s, when it described machines capable of performing tasks autonomously and replacing certain forms of human labor. Today, the term generally refers to subdomains such as machine learning (ML), where algorithms learn from data to make predictions or decisions, and deep learning, which uses neural networks to process complex datasets. It also encompasses generative techniques that can produce new information based on existing data (Schwendicke et al., 2020). Nevertheless, debates on automation and sustainable entrepreneurship emphasize that the integration of AI is not purely technological; it interacts with societal values, regulatory norms, and market dynamics, which can either accelerate or constrain its entrepreneurial applications (Farayola, 2023).

The 2010s ushered in the use of ML and neural networks for large-scale data analysis to monitor customer relationships, quicker responses to customer needs, and enhanced operational efficiency (Dwivedi et al., 2021). The growth of cloud computing and the demand for big data analytics further accelerated the adoption of AI technologies. AI-driven strategies that improve customer experience and support decision-making are now accessible to both startups and established firms (Güner Gültekin et al., 2025). For example, personalized recommendation systems and AI-based chatbots have become widespread in e-commerce, fundamentally changing how businesses interact with customers (Ameen et al., 2021; Tula, 2024). Nonetheless, adoption remains uneven: while some ventures leverage AI to innovate rapidly, others encounter barriers such as limited expertise, data limitations, or institutional uncertainty. This demonstrates that the transformative potential of AI depends on broader environmental and organizational conditions (Farayola, 2023; Usman et al., 2024).

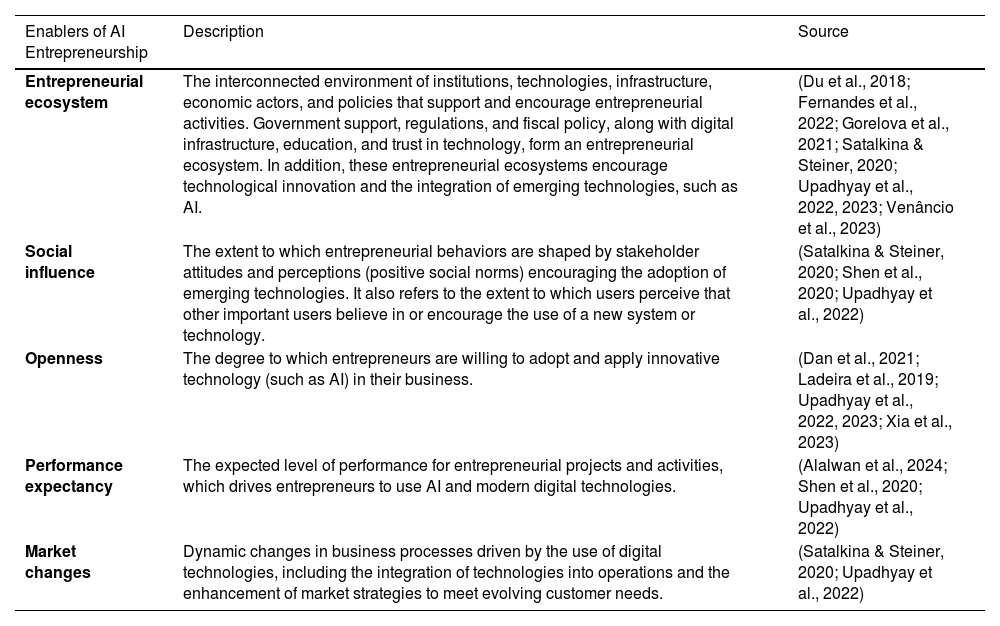

Enablers of artificial intelligence entrepreneurshipTo identify the factors that contribute to AI-based entrepreneurship and to address RQ1 (What are the components of the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem?), a content analysis of relevant studies was conducted. Content analysis accommodates a wide range of data and organizes phenomena into defined categories, allowing for more effective analysis and interpretation (Harwood & Garry, 2003). The Web of Science database was searched using the following keywords: digital enterprise, online enterprise, e-business enterprise, internet enterprise, AI enterprise, and predictor as a determinant or antecedent in the subject field of the documents. A total of 68 articles were retrieved, of which 45 were retained after a data screening process. The data were analyzed using Ligre v.6.5.1 software (Logiciels Ex-l-tec, 2024), which identified the following factors facilitating AI-based entrepreneurship: market changes, social influence, performance expectancy, openness, and the entrepreneurial ecosystem (Table 1).

Content analysis results.

| Enablers of AI Entrepreneurship | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Entrepreneurial ecosystem | The interconnected environment of institutions, technologies, infrastructure, economic actors, and policies that support and encourage entrepreneurial activities. Government support, regulations, and fiscal policy, along with digital infrastructure, education, and trust in technology, form an entrepreneurial ecosystem. In addition, these entrepreneurial ecosystems encourage technological innovation and the integration of emerging technologies, such as AI. | (Du et al., 2018; Fernandes et al., 2022; Gorelova et al., 2021; Satalkina & Steiner, 2020; Upadhyay et al., 2022, 2023; Venâncio et al., 2023) |

| Social influence | The extent to which entrepreneurial behaviors are shaped by stakeholder attitudes and perceptions (positive social norms) encouraging the adoption of emerging technologies. It also refers to the extent to which users perceive that other important users believe in or encourage the use of a new system or technology. | (Satalkina & Steiner, 2020; Shen et al., 2020; Upadhyay et al., 2022) |

| Openness | The degree to which entrepreneurs are willing to adopt and apply innovative technology (such as AI) in their business. | (Dan et al., 2021; Ladeira et al., 2019; Upadhyay et al., 2022, 2023; Xia et al., 2023) |

| Performance expectancy | The expected level of performance for entrepreneurial projects and activities, which drives entrepreneurs to use AI and modern digital technologies. | (Alalwan et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2020; Upadhyay et al., 2022) |

| Market changes | Dynamic changes in business processes driven by the use of digital technologies, including the integration of technologies into operations and the enhancement of market strategies to meet evolving customer needs. | (Satalkina & Steiner, 2020; Upadhyay et al., 2022) |

Source: Authors.

While these enablers frequently appear in research, prior findings are not always consistent. For example, some studies suggest that strong ecosystems guarantee the adoption of emerging technologies (Du et al., 2018; Venâncio et al., 2023), whereas others show that even in highly digitized contexts, AI adoption remains low owing to regulatory uncertainty or cultural barriers (Upadhyay et al., 2023). Similarly, social influence is often portrayed as positive, yet excessive reliance on prevailing norms may suppress experimentation, creating potential non-linear effects (Shen et al., 2020). These inconsistencies suggest that enablers do not operate uniformly across contexts and that their effects depend on the following multi-level conditions: macro (ecosystem and market), meso (social influence), and micro (openness and performance expectancy).

Although many studies examine the factors that encourage digital entrepreneurship, relatively few—such as Upadhyay et al. (2022, 2023)—focus specifically on the integration of AI technologies into digital entrepreneurship. For instance, social influence can be partly embedded within the entrepreneurial ecosystem (through institutional norms and policy pressures), while openness and performance expectancy may act sequentially rather than simultaneously (Upadhyay et al., 2022). Integrating dynamic capabilities theory (Teece, 2018) and institutional theory (Larsen, 2021) helps explain why access to resources alone is insufficient without the ability to sense opportunities, reconfigure routines, and secure social legitimacy for AI ventures.

Ecosystems also evolve through networks of cooperation and competition among actors (Mir et al., 2023; Stam & Van de Ven, 2021), supported by favorable policies and economic incentives (Sufyan et al., 2023). Social norms influence adoption but depend on openness to experimentation and learning (Shen et al., 2020; Upadhyay et al., 2022). Openness distinguishes innovators from non-innovators (Dan et al., 2021; Ladeira et al., 2019; Xia et al., 2023), but it translates into adoption only when entrepreneurs perceive clear performance benefits such as efficiency gains and error reduction (Alalwan et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2020). Finally, market changes—driven by competition, technological shifts, and consumer preferences—can stimulate AI adoption (Popescu et al., 2023; Satalkina & Steiner, 2020) or delay it under conditions of high uncertainty (Usman et al., 2024).

Hypothesis developmentMarket enablersAn entrepreneurial ecosystem encompasses financial institutions, cultural and social norms, government policies, and education providers that collectively support entrepreneurial activity (Pricopoaia et al., 2024). Effective ecosystems draw on a combination of resources, mentoring, leadership, and institutional support to foster innovation (Dabbous & Boustani, 2023; Lv et al., 2021; Shi et al., 2020). Previous research suggests that such ecosystems can facilitate AI adoption and strengthen entrepreneurial intentions by providing infrastructure, expertise, and favorable conditions for early-stage ventures (Ireta-Sanchez, 2024; Mammadov et al., 2024)). However, findings remain inconsistent; even in the presence of strong ecosystems, AI entrepreneurship may stagnate when access to resources is uneven or when institutional frameworks fail to ensure technology legitimacy and risk-taking (Lv et al., 2021; Upadhyay et al., 2023). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): A supportive entrepreneurial ecosystem positively influences AI entrepreneurial intention.

Social influence includes subjective norms, social support, and image-related factors that shape entrepreneurs’ decisions to adopt innovative technologies (Setyawati et al., 2023; Shen et al., 2020). Previous studies suggest that social influence may foster behaviour intention to use new twchnologies (Cioc et al., 2023), societal expectations can reduce perceived risks and encourage entrepreneurial intentions (Pratama & Kristanto, 2020; Saraih et al., 2018), while social intelligence and support networks further reinforce these intentions (Alcívar et al., 2023; Dabbous & Boustani, 2023; Mir et al., 2023). However, empirical results are mixed (Graf-Vlachy et al., 2018). In contexts where AI adoption is met with skepticism or unclear norms, social influence may fail to stimulate—and may even suppress—entrepreneurial action. These inconsistencies suggest that social influence functions as a driver of AI entrepreneurship primarily when normative and institutional conditions are supportive. For example, a recent study by Du et al. (2025) found that peer or institutional pressure does not influence either the intention or the actual behavior of adopting AI. The authors attribute this to the early stage of technology and the absence of well-defined social norms, highlighting the importance of a supportive organizational culture for social influence to become meaningful. Nonetheless, social influence can exert pressure on entrepreneurs to integrate emerging technologies. Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Social influence stimulates entrepreneurs’ intention to engage in AI-driven ventures.

Openness and performance expectancy are key mechanisms through which external enablers translate into AI entrepreneurial intentions. Openness reflects entrepreneurs’ willingness to explore and adopt AI technologies (Awwad & Al-Aseer, 2021; Sarwar et al., 2023; Upadhyay et al., 2022; Xu, 2023). Although often associated with stronger entrepreneurial intentions, openness alone does not ensure adoption in the absence of clear perceived benefits. Performance expectancy refers to the anticipated efficiency gains and error reduction from AI use (Alalwan et al., 2024; Simba et al., 2024), which influence intentions across different domains (Cheng et al., 2022; Dabbous & Boustani, 2023).

External enablers such as ecosystem support and social influence provide resources, legitimacy, and encouragement for experimentation (Upadhyay et al., 2022). Their impact is largely indirect: they foster openness to innovation and shape beliefs about the value of AI, which ultimately drive entrepreneurial intentions. From this perspective, supportive environments enable—but do not automatically generate—AI entrepreneurship without cognitive engagement from entrepreneurs. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed:

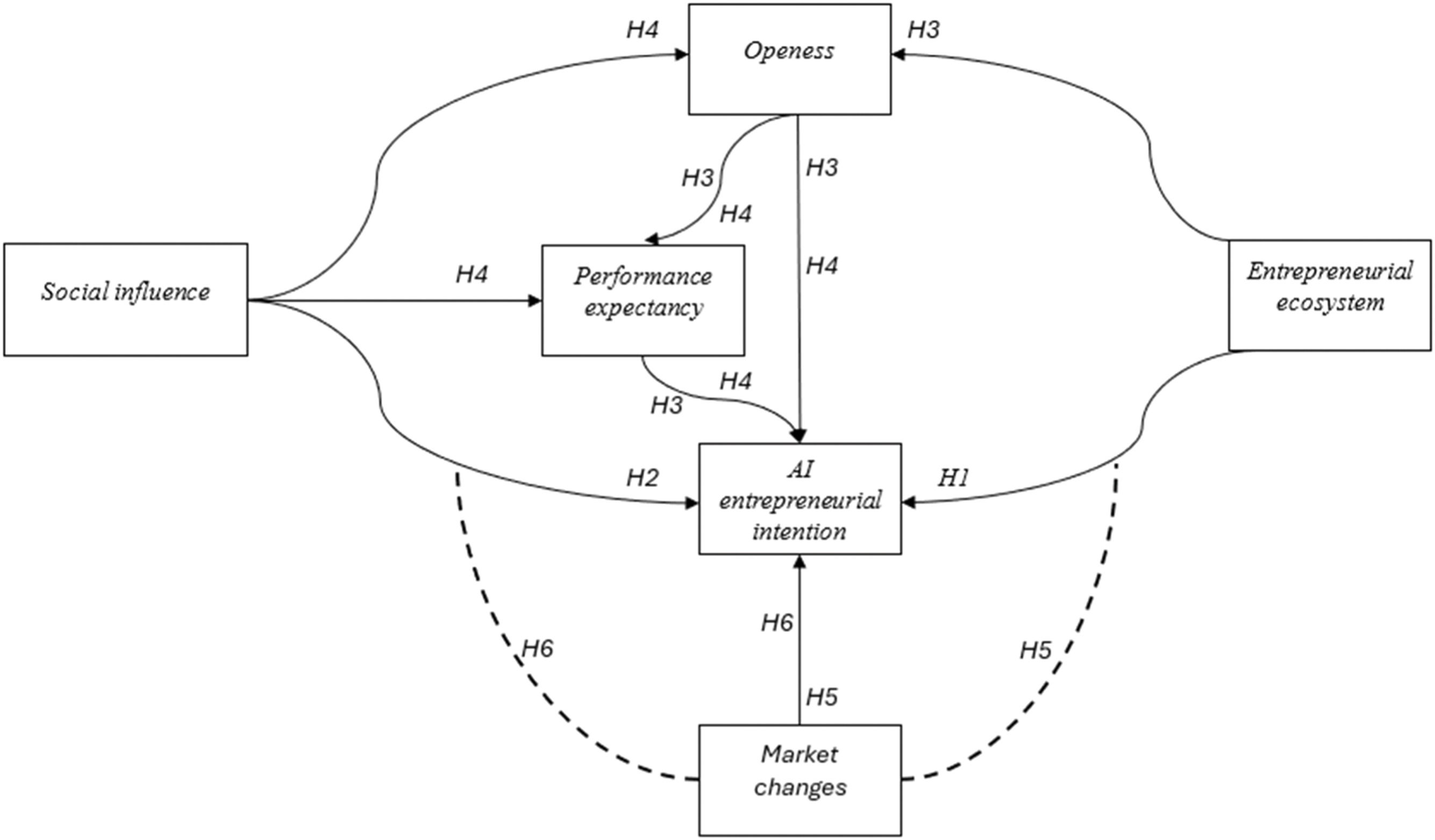

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Openness and performance expectancy mediate the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and AI entrepreneurial intention.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Openness and performance expectancy mediate the relationship between social influence and AI entrepreneurial intention.

Market dynamics—characterized by political and regulatory changes, competitive pressures, and shifting consumer preferences—are reshaping entrepreneurial ecosystems by altering access to resources, expertise, and emerging technologies (Mir et al., 2023; Stam, 2015). Evidence suggests that such changes can amplify the effects of supportive ecosystems, prompting entrepreneurs to adopt AI solutions relatively fast to remain competitive (Usman et al., 2024). However, in contexts with low digital literacy or inconsistent policies, ecosystem resources may not translate into higher entrepreneurial intention (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Ekawarna, 2022; Suganda & Simbolon, 2023). Moreover, social norms and stakeholder expectations influence entrepreneurial action (Suganda & Simbolon, 2023), but their impact on AI adoption is not uniform. In highly dynamic markets, social pressure to respond to rapid technological changes and evolving customer demands strengthens the link between social influence and entrepreneurial intention (Usman et al., 2024). Conversely, in more stable markets or under high regulatory uncertainty, social support alone may be insufficient to stimulate AI-oriented initiatives (Dwivedi et al., 2021; Ekawarna, 2022). Considering these factors, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 5 (H5): The strength of the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and AI entrepreneurial intention increases under conditions of greater market change.

Hypothesis 6 (H6): The influence of social factors on AI entrepreneurial intention becomes stronger in dynamic and changing market environments.

This study’s methodological framework is designed to extend the analysis by identifying potential areas for managerial intervention that could enhance entrepreneurial intention (Fig. 1).

Recent studies in the management field have emphasized the advantages of PLS-SEM for estimating complex models, particularly in testing theoretical frameworks and research hypotheses from a prediction-oriented perspective. This approach accommodates hierarchical constructs and allows the use of subsequent methods to enrich the basic results (Hair et al., 2019).

However, recent studies have highlighted the limitations of relying solely on PLS-SEM and have advocated for a more comprehensive approach that combines PLS-SEM with advanced techniques, enabling triangulation to enhance result validity (Cepeda et al., 2024). Therefore, this study adopts a multi-step approach based on PLS-SEM, combined IPMA and NCA (cIPMA) (Hauff et al., 2024; Sarstedt et al., 2024), and ANN (Fig. 2).

Steps of the combined PLS-SEM – cIPMA – ANN analysis.

PLS-SEM is widely used to test causal relationships between latent variables and to estimate direct, indirect (mediation), and moderating effects (Hair et al., 2022). Additionally, following sufficiency logic, IPMA identifies antecedent constructs with high importance but low performance, indicating where managerial interventions could have the greatest impact. According to necessity logic, NCA determines the set of antecedent conditions that must be present for a specific outcome to occur (Richter et al., 2020). The cIPMA integrates their sufficiency and necessity logic into a unified perspective (Hauff et al., 2024; Sarstedt et al., 2024; Ștefan et al., 2025), providing a graphical representation of antecedents across the four IPMA quadrants while indicating whether each is necessary and, if so, the proportion of cases that do not meet the condition (Hauff et al., 2024; Sarstedt et al., 2024).

Moreover, ANN are ML tools designed to mimic brain functions by identifying latent relationships in training data and evaluating them in test datasets. An ANN model includes input and output layers and at least one hidden layer connected by an activation function (Sharma et al., 2021). Integrating ANN with PLS-SEM allows the analysis of nonlinear relationships, enabling a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the AI entrepreneurial ecosystem with improved predictive performance (Mkedder & Özata, 2024).

Although recent business and management studies have complemented PLS-SEM results with IPMA (Bunea et al., 2024), NCA (Oliveira & Gomes, 2024), (or cIPMA) (Hauff et al., 2024; Ștefan et al., 2025), or with ANN (Lee et al., 2024b), few have employed such a comprehensive, multi-method design (Khatri et al., 2023). This hybrid analytical framework allows triangulation of research findings, enhancing the reliability and validity of conclusions and providing a robust foundation for theoretical and managerial implications (Sharma et al., 2021). SPSS Statistics v.29.0 (IBM Corp., 2024) was used for data preparation, preliminary analysis, and building ANN models, while PLS-SEM and cIPMA analyses were conducted using SmartPLS 4.1.9 (Ringle et al., 2024).

Data collectionThis study employed a self-administered online questionnaire to assess entrepreneurial intentions regarding AI. This approach facilitates the collection of a large volume of data and minimizes potential influence on respondents’ answers. The questionnaire was distributed online between May and September 2024 and completed by 825 individuals who indicated intentions to engage in entrepreneurial activities in the near future. This criterion was confirmed through the survey’s initial screening question. No monetary or material incentives were offered; instead, voluntary participation and anonymity were emphasized to encourage honest and thoughtful responses, particularly among a population where intrinsic motivation can improve data quality.

ScalesThe questionnaire employed a five-point Likert scale across the following six constructs:

- •

AI entrepreneurial intention (AIEI) assessed entrepreneurial intention in the context of AI technologies. The seven items in this construct were based on theoretical sources of digital entrepreneurial intention (Aloulou et al., 2024; Wibowo et al., 2023) but were adapted to the AI context.

- •

Entrepreneurial ecosystem (ENECOS) examined cultural and social norms, government support and policies, internal market openness, entrepreneurial education, AI training, and support in terms of taxes and bureaucracy in the context of digital entrepreneurship (Gheith, 2020), adapted to AI entrepreneurship intention.

- •

Social influence (SOCINF) comprised three sub-constructs: subjective norms, social factors, and image factors, which affect the adoption and integration of AI technology in entrepreneurship. The items were developed by the authors based on previous research (Upadhyay et al., 2022; Venkatesh et al., 2003).

- •

Openness (OPEN) was measured using six items created by the authors to assess entrepreneurs’ willingness to explore and implement AI technologies, including statements such as “I am open to exploring and learning about AI.”

- •

Performance expectancy (PERFEX) included five items measuring the expected benefits and outcomes from using and integrating AI technologies. The construct was inspired by Venkatesh et al. (2003) but adapted specifically to the AI context.

- •

Market changes (MKCH) consisted of four items developed by the authors to capture changes resulting from AI adoption at the consumer level, competitive environment, and overall market trends.

The final dataset comprised 765 cases (excluding 45 cases with missing data or suspicious response patterns and 15 cases that were not part of the research population). This sample size exceeded the minimum requirements for estimating the PLS-SEM model, as assessed by a G*Power analysis, with f2=0.15,α=0.05,power=0.80, and five predictors, which indicated a minimum of 92 cases, and the inverse square root method (Kock & Hadaya, 2016), which, for βmin=0.20 and α = 0.05, indicated a minimum of 155 cases. The presence of outliers and the distribution of the data were also evaluated. No corrective measures were necessary, as no extreme values were identified, and skewness (between −0.643 and 0.231) and kurtosis (−1.119 and −0.400) values did not indicate deviations from normality.

In addition to these statistical checks, the questionnaire design separated independent and dependent measures and varied item wording and scale formats. Harman’s single-factor test showed that the first factor accounted for 53.81 % of the variance. This result, together with the strong reliability and validity of the constructs, suggests that common method bias was unlikely to meaningfully affect the findings (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

In the final dataset, most participants were women (61.961 %), had at least a bachelor’s degree (82.222 %), and had an average age of 30.148 years. The majority were employed (82.082 %), while only 38.562 % were students.

Partial least squares structural equation modeling analysisTo address RQ2 (How does the AI entrepreneurial ecosystem contribute to the growth of AI entrepreneurial intentions?), a PLS-SEM model was first specified to evaluate the research hypotheses, followed by a subsequent cIPMA analysis. The analysis of the PLS-SEM model followed standard procedures (Hair et al., 2019), including evaluation of the measurement model, assessment of the structural model, and testing of the research hypotheses. As the model included two multidimensional constructs, they were specified as reflective-reflective hierarchical constructs using the disjointed two-stage approach. In the first stage, the measurement model was evaluated for all lower-order components, and their scores were then used as indicators of higher-order constructs in the second stage (Hair et al., 2024).

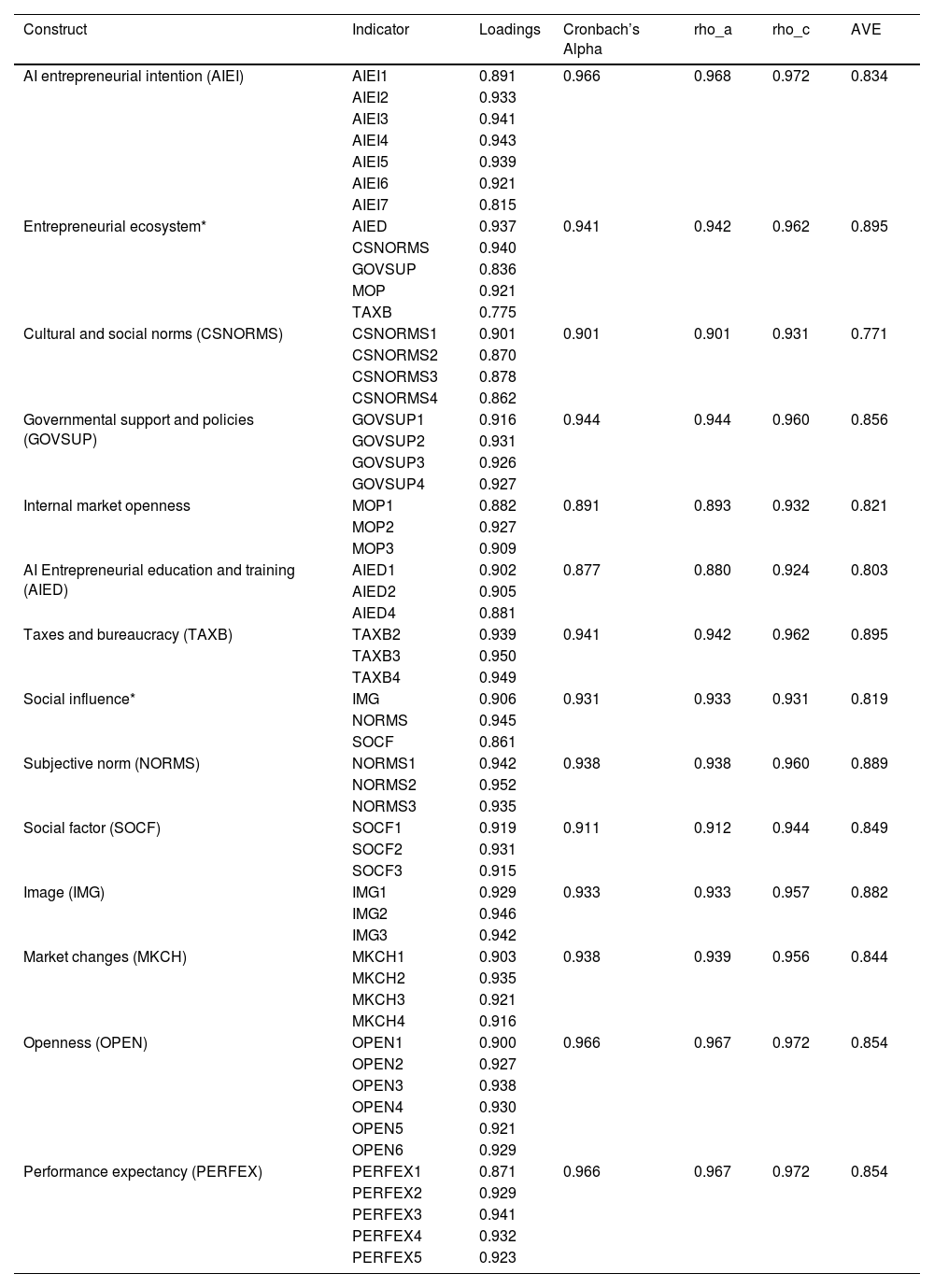

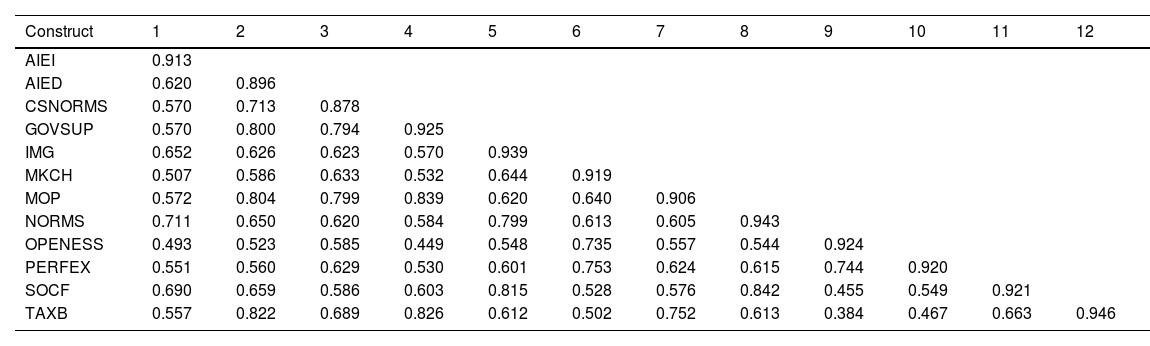

Indicator loadings (> 0.708), Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (> 0.7), and composite reliability (> 0.7) confirmed the indicator reliability and internal consistency of the measurement model (Table A1). Additionally, average variance extracted values (> 0.7) (Table A1), the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Table A2), and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (Table A3) supported the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs.

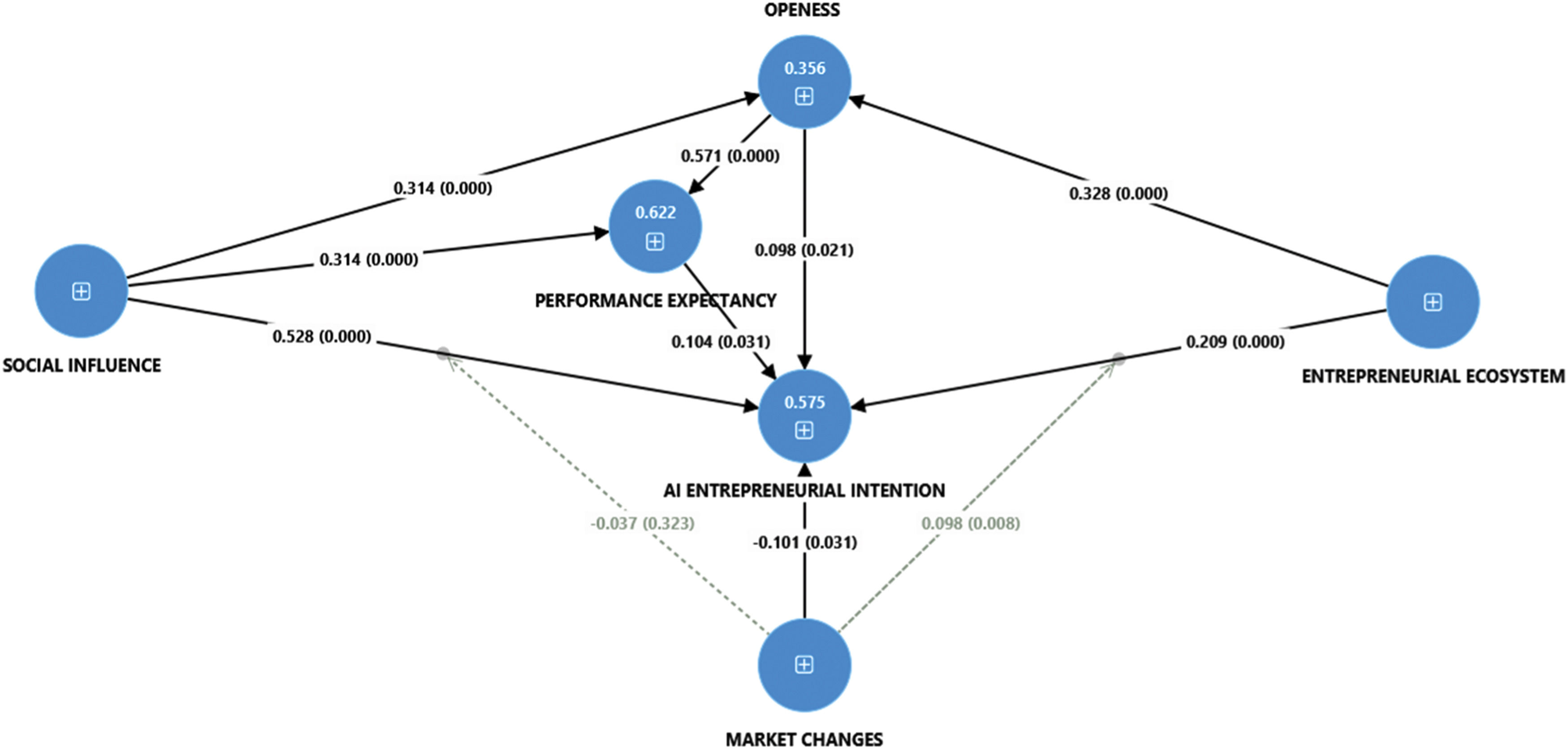

The structural model (Fig. 3) was first examined for collinearity, with no variance inflation factor values indicating concern. In-sample explanatory power was evaluated using the coefficients of determination, which showed moderate explanatory power for OPEN (R2=0.356) and high explanatory power for PERFEX (R2=0.622)and AIEI (R2=0.575)(Hair et al., 2019). Out-of-sample predictive power was assessed using the PLSpredict procedure (Shmueli et al., 2019) with 10 folds and 10 repetitions. Focusing on the AIEI target construct, all indicators had QPredict2 values greater than zero, and the PLS-SEM model produced smaller prediction errors than the linear model for one indicator based on root mean square error (RMSE) and for three indicators based on mean absolute error. These results indicate that the PLS path model outperforms the naïve benchmark and demonstrates low to medium out-of-sample predictive power.

Structural model. Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

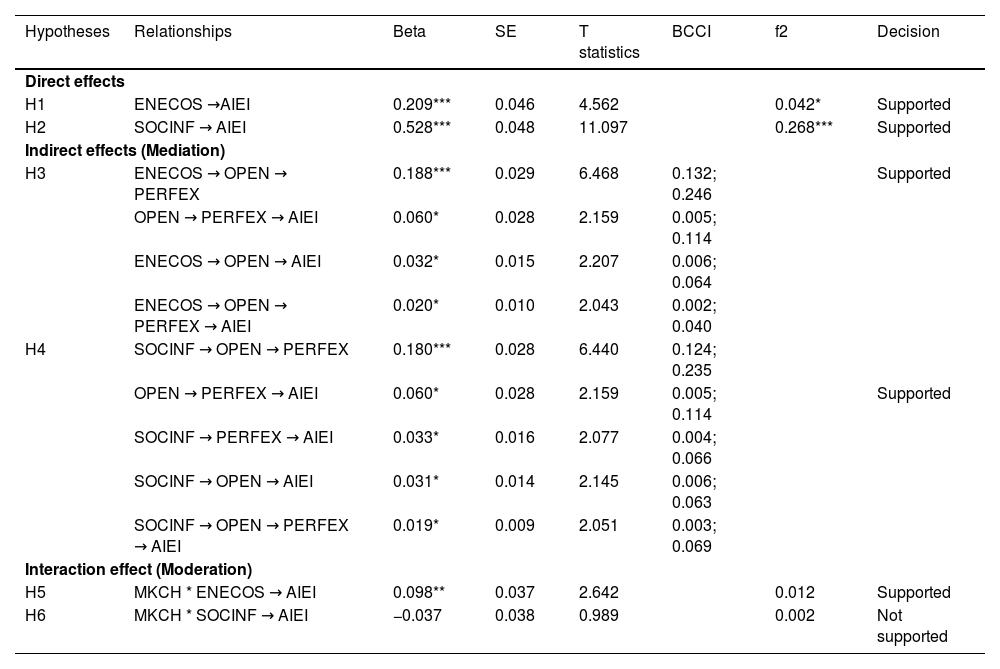

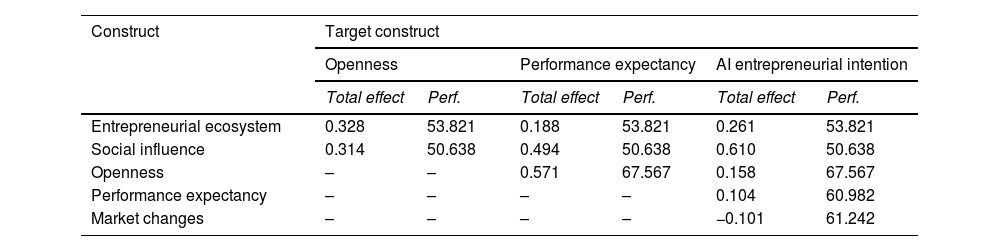

All path coefficients (direct relationships) between the constructs of the structural model were statistically significant, allowing them to be interpreted and used to validate the research hypotheses. Table 2 shows that ENECOS and SOCINF have positive effects on AIEI, confirming H1 and H2. These results indicate that even modest improvements in ecosystem quality or social influence can lead to meaningful increases in the likelihood of launching an AI-based venture, particularly when applied across the entrepreneurial population.

Direct, indirect, and moderated effects.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

Moreover, the significant specific indirect effects, estimated using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples, together with the direct effects, support the complex complementary mediation of OPEN and PERFEX in the ENECOS → AIEI and SOCINF → AIEI relationships, thus confirming H3 and H4 (Nitzl et al., 2016). Regarding the final two hypotheses, MKCH positively moderates the ENECOS → AIEI relationship, such that higher levels of MKCH strengthen the positive effect of ENECOS on AIEI. However, although MKCH appears to weaken the effect of SOCINF on AIEI, this moderation effect is not statistically significant. In other words, when social influence is already high, additional variability from market dynamics does not substantially alter entrepreneurial intentions. Consequently, H5 is supported, whereas H6 is not.

Combined IPMA and NCA analysisA construct-level IPMA was conducted by comparing the rescaled scores of AI ecosystem dimensions, derived from PLS-SEM, with their total effects on AI entrepreneurial intention, thereby identifying areas with potential for improvement (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 4(a), (b), and (c), managerial interventions aimed at fostering AI entrepreneurial intention should prioritize social influences and the entrepreneurial ecosystem, which exhibit high importance (total effect) but relatively low performance, indicating room for improvement. Strengthening social influence can also enhance performance expectations regarding AI entrepreneurship. Additionally, the IPMA results suggest that the current approaches to performance expectancy and entrepreneurs’ openness, as well as to the entrepreneurial ecosystem, should be maintained.

Importance-performance analysis for the full model.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

cIPMA.

● = not necessary; ◯ = necessary. Bubble sizes represent the percentage of cases that do not meet the necessary condition for achieving 85 % of the target construct.

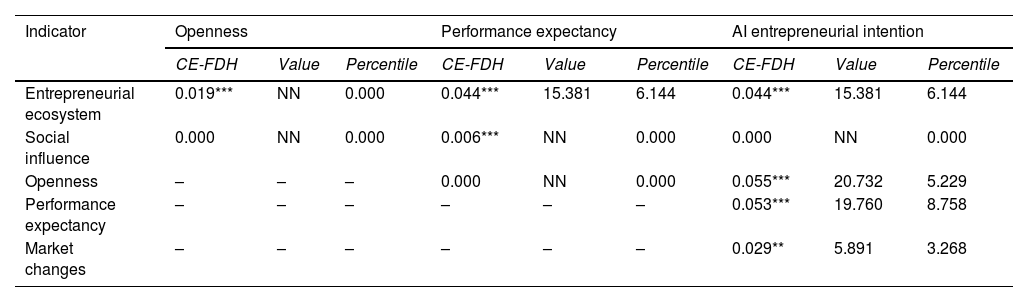

Regarding RQ3 (What dimensions of the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem condition AI entrepreneurial intention?), the rescaled scores of the latent PLS-SEM constructs were used to create bottleneck tables and identify the set of conditions necessary to achieve 85 % of each target construct (on a 0–100 scale). The percentiles indicate the proportion of cases not meeting these conditions, and the necessity effect size was computed using the CE-FDH technique (Richter et al., 2020). Table 4 shows that, to reach 85 % AI entrepreneurial intention, four conditions must be satisfied: ENECOS, OPEN, PERFEX, and MKCH, with minimum values of 15.381, 20.732, 19.760, and 5.891, respectively, on a 1–100 scale. For a performance expectancy of 85 %, ENECOS must reach at least 15.381, while OPEN does not have a necessary threshold. Although these necessary conditions must be met to guarantee 85 % performance expectancy and AI entrepreneurial intention, the proportion of cases not meeting these levels was relatively low, ranging from 3.268 % for MKCH to 8.758 % for PERFEX.

Necessary conditions analysis for the full model.

Source: Authors' calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

Integrating the percentile values from the NCA into the four-quadrant IPMA matrix (Hauff et al., 2024; Sarstedt et al., 2024) (Fig. 4 (a–c)) enhances the interpretation of the findings. For example, even though ENECOS has a low priority in fostering performance expectancy (Fig. 4b), a minimum level of 15.381 is a necessary condition, which 6.144 % of the cases do not meet. Similarly, while the IPMA suggests that OPEN, PERFEX, and MKCH may exceed the level required for AI entrepreneurial intention (Fig. 4c), a minimum level of each is still required. While SOCINF has no required threshold, the IPMA results indicate that managers should focus on improving its performance to enhance both performance expectancy (Fig. 4b) and AI entrepreneurial intention (Fig. 4c).

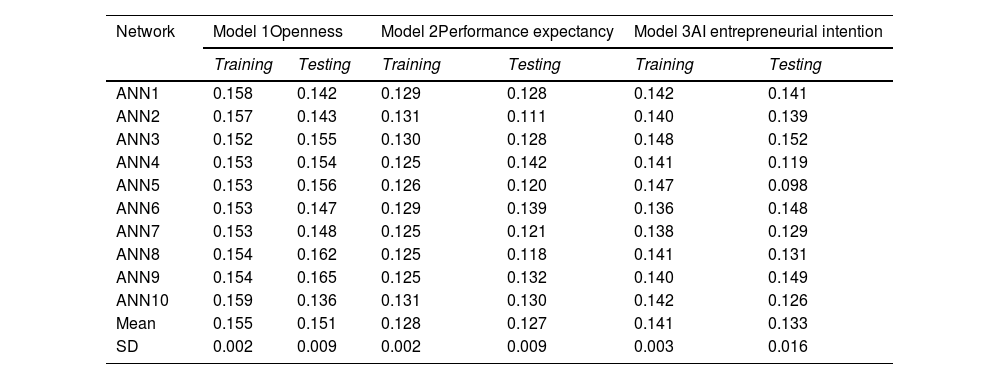

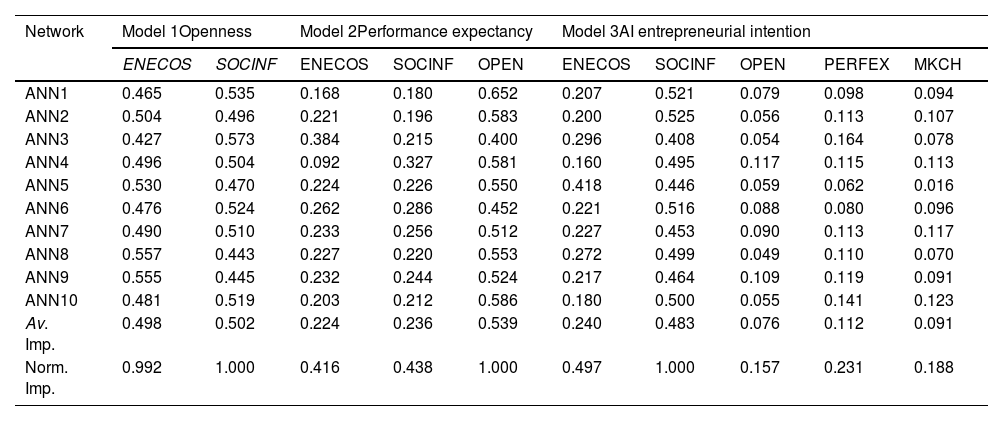

Artificial neural networks analysisThree ANN models were developed, each corresponding to one of the three target variables considered in the cIPMA stage: Model 1 – openness, Model 2 – performance expectancy, and Model 3 – AI entrepreneurial intention (Fig. 5 (a–c)). Following established guidelines (Mkedder & Özata, 2024; Sharma et al., 2021), a feed-forward backpropagation multilayer training algorithm with a sigmoid activation function was applied to both the hidden and output layers, with the hidden neuron layer created automatically. Additionally, 90 % of the data points were used for training, and the remaining 10 % were reserved for testing (Kumar et al., 2023).

To validate the ANN models, RMSE accuracy measures were computed for ten networks, representing the errors in both training and testing. RMSE values for Models 1–3 are presented in Table A4 for the training and testing subsamples. The small mean RMSE values (ranging from 0.126 to 0.155), low variation around the mean, and minimal differences between the training and testing subsamples support the reliability of the ANN results (Kumar et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2021).

Each model’s sensitivity analysis was computed based on the normalized average importance of the input variables in predicting the output variables of the ANN models (Models 1–3) (Kumar et al., 2023; Sharma et al., 2021). The results are summarized in Table A5. The sensitivity analysis indicates that ENECOS and SOCINF are both important predictors of OPEN (Model 1), with SOCINF having a slightly higher average importance (0.502 vs. 0.498). For performance expectancy (Model 2), the output is primarily predicted by OPEN (average importance: 0.539), followed by SOCINF (0.236) and ENECOS (0.224). In Model 3, the strongest predictor of AIEI is SOCINF (0.483), followed by ENECOS (0.240) and PERFEX (0.112), while all other predictors have average importance below 0.1.

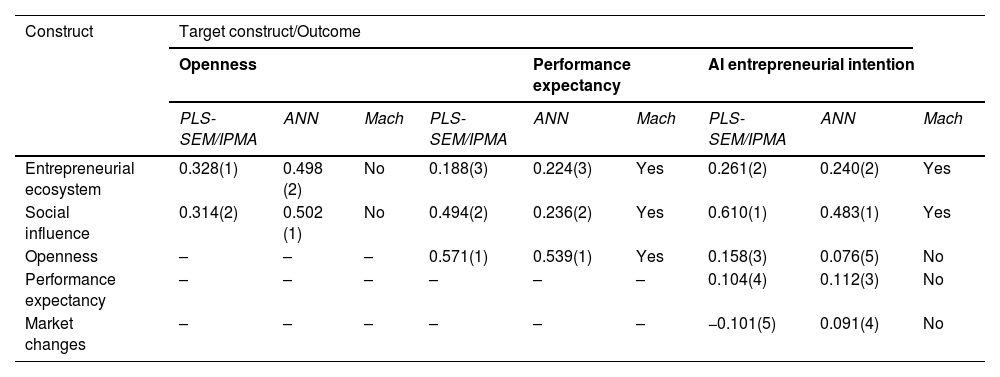

Table 5 compares the ranking of total effects derived from PLS-SEM and IPMA with the average importance of predictors obtained from the ANN for each model. The results show that SOCINF and ENECOS are the most important predictors of AIEI and PERFEX, ranked first and second, respectively. For Model 1, although the predictor rankings did not perfectly align, the differences in total effect (PLS-SEM/IPMA) and average importance (ANN) were minimal. Overall, the ANN analysis validates the PLS-SEM results while also accounting for nonlinear relationships among the constructs (Duc et al., 2023).

Partial least squares structural equation modeling/importance-performance analysis and artificial neural networks ranking importance.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024) and SPSS Statistics v.29.0 (IBM Corp. (2024).

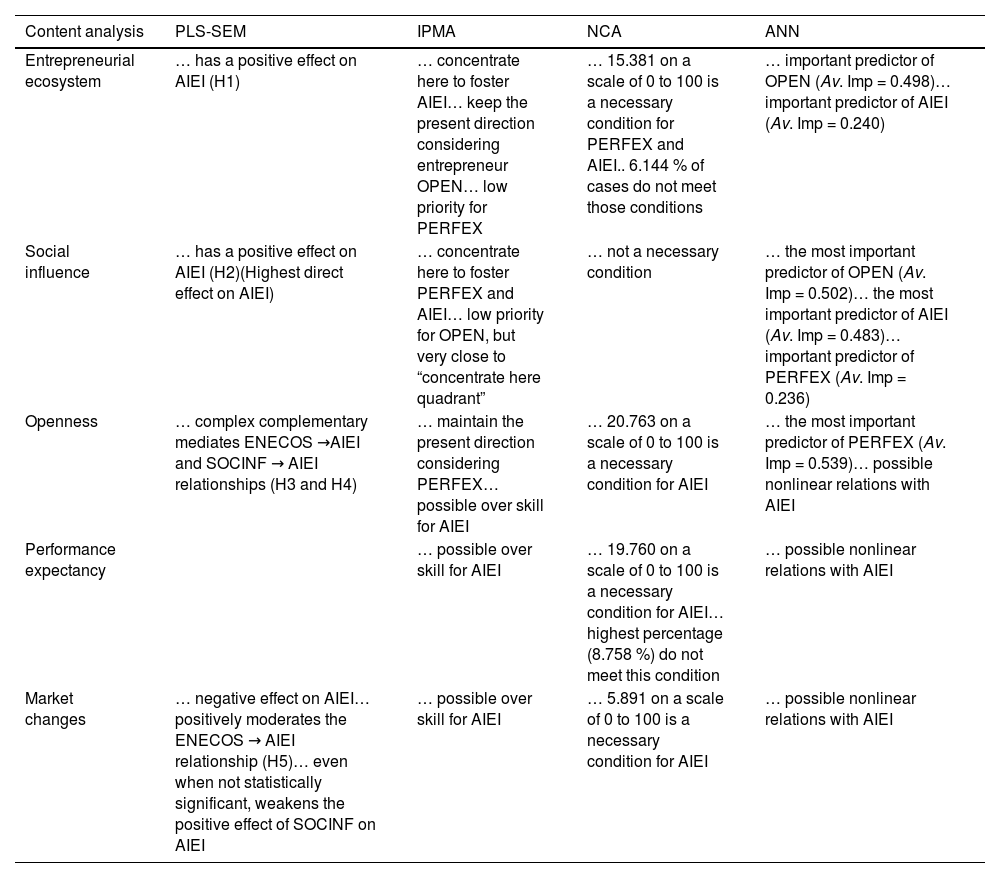

Table 6 presents the results for each dimension of the AI entrepreneurial ecosystem across all methodological approaches.

Main results.

Source: Authors.

The main results indicate that the entrepreneurial ecosystem has a positive effect on AI entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, environmental factors—such as cultural and social norms, government support and policies, openness of the internal market, AI-focused entrepreneurial education and training, and tax support and bureaucracy—positively influence the intention to use AI in starting a business. These findings align with prior studies showing that the entrepreneurial ecosystem, through its determinants, contributes to increased entrepreneurial intentions (Dabbous & Boustani, 2023; Lv et al., 2021; Mammatov et al., 2024; Shi et al., 2020). Moreover, the results underscore that the entrepreneurial ecosystem is a key factor, suggesting that managerial interventions should focus on strengthening the AI entrepreneurial ecosystem. Such interventions are necessary to enhance expected performance in AI use—such as completing tasks faster, improving productivity, reducing errors, and enhancing quality—as well as to increase AI entrepreneurial intention. Additionally, the entrepreneurial ecosystem is an important predictor of both openness and AI entrepreneurial intention. Specifically, the greater the support from factors such as cultural and governmental influences, the higher entrepreneurs’ openness to AI becomes, making them more willing to explore, learn, and adopt AI, while simultaneously boosting their entrepreneurial intention to use it.

Social influence, which includes subjective norms, social factors, and image considerations, was found to have the strongest direct positive impact on entrepreneurial intention to use AI tools when starting a business. These findings reinforce prior research linking social enablers—such as subjective norms, social adroitness, social support, and social norms—to entrepreneurial intentions (Alcívar et al., 2023; Dabbous & Boustani, 2023; Mir et al., 2023; Pratama & Kristanto, 2020; Saraih et al., 2018). The results suggest that managerial interventions should target social influence to enhance expected performance in AI use and AI entrepreneurial intention. Conversely, while social influence is not a necessary condition for other enablers of AI entrepreneurship, it remains the strongest predictor of entrepreneurs’ openness to AI and their intention to adopt it. It is also an important predictor of expected performance in the use and integration of AI technologies.

Openness is another critical enabler of AI entrepreneurship. The results indicate that openness mediates the relationships between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and AI entrepreneurial intention, and between social influence and AI entrepreneurial intention. As social appetite for AI and willingness to adopt new technologies increase, entrepreneurs better understand how the socio-environmental context shapes their decisions, which in turn strengthens their intention to adopt AI. These findings suggest that openness is a necessary condition for increasing AI entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, entrepreneurial openness should be prioritized, as it is the most important predictor and enabler of enhanced performance expectancy when using AI. For example, Sarwar et al. (2023) show that openness to new experiences is a determinant of entrepreneurial intention among students. Similarly, Ștefan et al. (2024) confirm that individuals who are more open to innovative technologies, such as AI, are more likely to integrate these technologies into future entrepreneurial activities.

Another enabler of AI entrepreneurship is performance expectancy, which refers to entrepreneurs’ expectations of the benefits of implementing AI technology in their business, such as faster task completion, higher productivity, improved work quality, fewer errors, and increased efficiency. The findings show that performance expectancy mediates both the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and AI entrepreneurial intention, and between social influence and AI entrepreneurial intention. Moreover, performance expectancy is a necessary condition for enhancing AI entrepreneurial intention. These results are consistent with those of Upadhyay et al. (2022, 2023), who show that high performance expectancy mediates the effects of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and social influence on AI entrepreneurial intention. Thus, the findings support the view that entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the potential benefits of AI must be reinforced by their environment and social pressures, which in turn shape their decisions to integrate AI into entrepreneurial activities.

Market changes—such as increased competition, rapid technological advancements, and shifts in consumer preferences—are also considered enablers of AI entrepreneurship. The results indicate that market changes have a negative direct effect on AI entrepreneurial intention but positively moderate the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and entrepreneurial intention to use AI technologies. However, the hypothesized moderation between social influence and AI entrepreneurial intention (H6) was not statistically supported. One possible explanation is that this study’s measurement of “market changes” captured a broad and heterogeneous set of environmental shifts, which may have diluted its specific interaction with social influence. Another plausible explanation lies in the contextual characteristics of the Romanian entrepreneurial environment, where social endorsement and interpersonal networks may retain their influence regardless of external market fluctuations. Additionally, the moderating effect may require a longer temporal horizon to emerge, as short-term market dynamics may not significantly alter the role of social influence in shaping AI-related intentions.

Nonetheless, although market changes negatively affect entrepreneurial intention directly, the NCA results indicate that they represent a necessary condition for increasing the likelihood of adopting AI tools when starting a business. This suggests that awareness of competitive and technological shifts is crucial for entrepreneurs to recognize the urgency of AI adoption, even if such changes initially seem disruptive. These findings are consistent with prior research: Wang et al. (2022) argue that market changes, while often perceived negatively owing to the uncertainty they generate, can enhance firms’ resilience and agility, enabling them to adapt to evolving customer demands and remain competitive. Similarly, Dwivedi et al. (2021) emphasize that external pressures can act as catalysts for technological integration when firms possess the capabilities to respond effectively.

Theoretical contributionsThis study addresses a knowledge gap by integrating entrepreneurial ecosystem theory (Stam & Spigel, 2016) with technology adoption perspectives (Upadhyay et al., 2022), two streams of research that have largely developed independently. The findings show that this integration occurs through openness and performance expectancy, offering a meaningful conceptual bridge. Additionally, the persistence of social influence even in turbulent markets reveals a boundary condition that challenges the common assumption in environmental dynamism research that external change diminishes normative factors of intention. This result extends existing theory by suggesting that, in emerging contexts, interpersonal trust and normative approval can counteract volatility, thereby stabilizing entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, integrating dynamic capabilities theory (Teece, 2018) with ecosystem perspectives underscores that enabling conditions alone are insufficient; entrepreneurs must also be able to reconfigure practices and experiment with AI to realize AI-driven entrepreneurial intentions.

Moreover, by combining PLS-SEM, IPMA, NCA, and ANN, the study demonstrates how the logic of sufficiency and necessity can be applied in entrepreneurial research. This multi-method approach enhances validity and offers a model capable of uncovering complex, context-dependent mechanisms for future studies.

Practical implicationsThis study’s findings offer actionable guidance for multiple stakeholders. For policymakers, the priority is to strengthen support for the AI ecosystem by funding targeted training programs, streamlining regulations, and introducing tax incentives or co-financing schemes for AI startups. For accelerators and incubators, the strong influence of social factors suggests investing in mutual learning, promoting visible role models, and developing mentoring networks that legitimize AI entrepreneurship. For entrepreneurs, the results emphasize the importance of cultivating openness and trust through hands-on experimentation, which can be facilitated by digital entrepreneurship labs, pilot projects, and rapid prototyping facilities.

The findings also indicate that market turbulence, although negatively associated with intention, can be reframed as an opportunity. Incubators and support programs can contribute by showcasing AI projects that have succeeded under uncertainty, thereby normalizing turbulence as an integral part of innovation rather than a barrier.

While the data are drawn from Romania, these results are transferable to other emerging ecosystems where digital infrastructure is developing but AI adoption remains uneven. Consequently, the framework and conclusions provide practical insights for international contexts facing similar challenges.

ConclusionsThis study makes a theoretical contribution by identifying the enablers of AI entrepreneurship and demonstrating how the component factors of the AI entrepreneurial ecosystem shape entrepreneurial intentions to use AI.

The first question addresses the components of the AI entrepreneurship ecosystem. The content analysis identified five determinants that promote AI entrepreneurial intention: the entrepreneurial ecosystem, social influence, openness to adopting innovative technologies, expected AI performance, and market changes.

Using the PLS-SEM approach, the entrepreneurial ecosystem and social influence were found to have significant direct effects on AI entrepreneurial intention. Openness to AI and performance expectancy emerged as mediating mechanisms that amplify these effects, indicating that favorable environmental conditions alone are insufficient without individual willingness to embrace AI. While market changes negatively influenced AI entrepreneurial intention directly, they positively moderated the relationship between the entrepreneurial ecosystem and intention, suggesting a potential adaptive response under competitive or volatile conditions. These findings extend prior literature by revealing a dual mediation pattern and highlighting the complex, context-dependent role of market dynamics.

The combined PLS-SEM–IPMA–NCA analysis showed that the entrepreneurial ecosystem, openness, social influence, and performance expectancy are necessary conditions for fostering AI entrepreneurial intention. IPMA results underscored the strategic importance of the entrepreneurial ecosystem and social influence, despite their relatively low performance levels. The ANN analysis further confirmed the robustness of these predictors, identifying social influence, entrepreneurial ecosystem, and performance expectancy as the most influential drivers of AI entrepreneurial intentions.

Limitations and future directionsRomania provides a lens for examining AI entrepreneurship within an emerging digital ecosystem. Although the sample is skewed toward younger and more educated respondents, this demographic corresponds to the typical profile of early AI adopters and aligns with methodological approaches in similar entrepreneurship research. Nonetheless, broader samples could improve the external validity of the findings. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, thus, future research would benefit from longitudinal studies to track the evolution of AI entrepreneurial intention over time. Comparative analyses across countries with varying levels of ecosystem maturity and digital readiness could further assess the framework’s generalizability. Additionally, exploring non-linear effects and more complex moderating relationships—particularly in relation to market changes—may provide deeper insights into the contingencies shaping AI entrepreneurship. Finally, this study did not distinguish between types of AI applications, such as generative AI, predictive analytics, or automation tools. Future research could examine whether different technologies elicit distinct patterns of entrepreneurial intention, openness, and dependence on ecosystem support, providing a more nuanced understanding of AI adoption dynamics.

CRediT authorship contribution statementSimona Cătălina Ștefan: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ion Popa: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Andreea Breazu: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis.

Authors declare no competing interests

The research presented in this paper was partially funded by the Academy of Romanian Scientists within the research project competition for young researchers „AOȘR-TEAMS-III”, 2024–2025 edition, project "Challenges and perspectives of organization management in the new paradigm of digital transformation". The present study was partially conducted within the framework of the doctoral programs in the Management field, at Bucharest University of Economic Studies.

Measurement model reliability and validity.

| Construct | Indicator | Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | rho_a | rho_c | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI entrepreneurial intention (AIEI) | AIEI1 | 0.891 | 0.966 | 0.968 | 0.972 | 0.834 |

| AIEI2 | 0.933 | |||||

| AIEI3 | 0.941 | |||||

| AIEI4 | 0.943 | |||||

| AIEI5 | 0.939 | |||||

| AIEI6 | 0.921 | |||||

| AIEI7 | 0.815 | |||||

| Entrepreneurial ecosystem* | AIED | 0.937 | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.962 | 0.895 |

| CSNORMS | 0.940 | |||||

| GOVSUP | 0.836 | |||||

| MOP | 0.921 | |||||

| TAXB | 0.775 | |||||

| Cultural and social norms (CSNORMS) | CSNORMS1 | 0.901 | 0.901 | 0.901 | 0.931 | 0.771 |

| CSNORMS2 | 0.870 | |||||

| CSNORMS3 | 0.878 | |||||

| CSNORMS4 | 0.862 | |||||

| Governmental support and policies (GOVSUP) | GOVSUP1 | 0.916 | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.960 | 0.856 |

| GOVSUP2 | 0.931 | |||||

| GOVSUP3 | 0.926 | |||||

| GOVSUP4 | 0.927 | |||||

| Internal market openness | MOP1 | 0.882 | 0.891 | 0.893 | 0.932 | 0.821 |

| MOP2 | 0.927 | |||||

| MOP3 | 0.909 | |||||

| AI Entrepreneurial education and training (AIED) | AIED1 | 0.902 | 0.877 | 0.880 | 0.924 | 0.803 |

| AIED2 | 0.905 | |||||

| AIED4 | 0.881 | |||||

| Taxes and bureaucracy (TAXB) | TAXB2 | 0.939 | 0.941 | 0.942 | 0.962 | 0.895 |

| TAXB3 | 0.950 | |||||

| TAXB4 | 0.949 | |||||

| Social influence* | IMG | 0.906 | 0.931 | 0.933 | 0.931 | 0.819 |

| NORMS | 0.945 | |||||

| SOCF | 0.861 | |||||

| Subjective norm (NORMS) | NORMS1 | 0.942 | 0.938 | 0.938 | 0.960 | 0.889 |

| NORMS2 | 0.952 | |||||

| NORMS3 | 0.935 | |||||

| Social factor (SOCF) | SOCF1 | 0.919 | 0.911 | 0.912 | 0.944 | 0.849 |

| SOCF2 | 0.931 | |||||

| SOCF3 | 0.915 | |||||

| Image (IMG) | IMG1 | 0.929 | 0.933 | 0.933 | 0.957 | 0.882 |

| IMG2 | 0.946 | |||||

| IMG3 | 0.942 | |||||

| Market changes (MKCH) | MKCH1 | 0.903 | 0.938 | 0.939 | 0.956 | 0.844 |

| MKCH2 | 0.935 | |||||

| MKCH3 | 0.921 | |||||

| MKCH4 | 0.916 | |||||

| Openness (OPEN) | OPEN1 | 0.900 | 0.966 | 0.967 | 0.972 | 0.854 |

| OPEN2 | 0.927 | |||||

| OPEN3 | 0.938 | |||||

| OPEN4 | 0.930 | |||||

| OPEN5 | 0.921 | |||||

| OPEN6 | 0.929 | |||||

| Performance expectancy (PERFEX) | PERFEX1 | 0.871 | 0.966 | 0.967 | 0.972 | 0.854 |

| PERFEX2 | 0.929 | |||||

| PERFEX3 | 0.941 | |||||

| PERFEX4 | 0.932 | |||||

| PERFEX5 | 0.923 |

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

Fornell-Larcker criterion.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

Heterotrait-monotrait ratio - Matrix.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SmartPLS 4 (Ringle et al., 2024).

RMSE values for ANN Models.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SPSS Statistics v.29.0 (IBM Corp. (2024).

RMSE values for ANN Models.

Source: Authors’ calculations using SPSS Statistics v.29.0 (IBM Corp. (2024).