In today's fast-paced digital landscape, the importance of human factors in cybersecurity has become increasingly evident yet is often overlooked. This research employs the Delphi method to achieve expert consensus on the managerial actions that enhance cybersecurity by leveraging human factors. The study offers 16 key managerial actions, highlighting the shift from viewing humans as sources of vulnerability to acknowledging them as essential components of cybersecurity solutions. The findings suggest developing an organizational culture that values cybersecurity, delineating clear roles and responsibilities, and fostering continuous learning. This approach emphasizes the importance for organizations to recalibrate their cybersecurity strategies and provides a roadmap for implementing the suggested managerial actions. The study contributes to the socio-technical debate with a particular focus on human factors and provides practical guidance for organizations to improve their future cybersecurity posture.

In today's hyper-connected environment, there has been a remarkable increase in productivity, efficiency, and system integration, ushering in a new era of digital evolution. However, this unprecedented connectivity has also introduced several potential risks (Corallo et al., 2020). Rapid digital transformation has made organizations highly dependent on data and information within their integrated systems, opening the door to new risk scenarios (Buck et al., 2023; Carroll et al., 2023). This dependency amplifies the impact of cyber threats, putting business continuity, confidentiality, and reputation at risk.

The latest European Digital SME Report reveals a significant escalation in ransomware attacks in 2023 and highlights the publication of 7772 new potential issues in the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database, further illustrating the dynamic and ever-changing nature of cyber vulnerabilities (European Digital, 2023). Mitnick and Simon (2003) noted that humans have become the most vulnerable aspect of systems. This statement remains relevant today due to the prevalence of cyber incidents driven by human involvement. According to Verizon's 2023 Data Breaches Investigations Report (Verizon, 2023), 72 % of data breaches involved a human element, including incidents related to social engineering attacks, errors, and misuse. IBM's 2023 Cost of a Data Breach Report (Cost of a data breach Report, 2023) identified human error as the cause of the most expensive forms of data breaches. The available data show a significant increase in incidents caused by inattention as the primary factor. In many cases, however, attributing incidents merely to oversight fails to fully capture the situation, because such incidents are often the result of a combination of human characteristics, workplace conditions (Donalds & Osei-Bryson, 2020; Neigel et al., 2020), and skill gaps (Aljohani et al., 2022). For years, organizations have relied on highly technical approaches that have only marginally considered human integration in their cybersecurity strategies. Investigations following numerous cyber incidents have consistently pointed to human error or negligence, identifying users as the weak link in establishing secure environments, with limited consideration given to end users' cognitive characteristics, needs, and motivations (Abzakh & Althunibat, 2023).

In this context, there is a growing interest in addressing the human aspects of cybersecurity by fostering an informed and proactive workforce (Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019). The field of study of human factors is defined as the "scientific discipline concerned with the understanding of the interactions among humans and elements of a system” (Bridger, 2018). As key aspects of cybersecurity, human factors are attracting increasing interest in this domain, due to their potential to frame humans as either a problem or a key part of the solution for cybersecurity (Desolda et al., 2021a). This focus has moved beyond a purely technological perspective, embracing a human-centric cybersecurity approach that prioritizes the design of security systems around user needs and behaviors while enhancing usability and reducing cognitive load (Warkentin et al., 2016). Additionally, through the socio-technical systems perspective, the technological aspects have been integrated with the social ones, enabling the analysis of the social, environmental, and technical aspects of cybersecurity and offering a multidimensional viewpoint (Malatji et al., 2019).

The intersection of human factors in cybersecurity and behavioral security theory offers valuable insights for mitigating risks by taking human behavior into account, ultimately improving overall security outcomes (Balozian et al., 2023; Chowdhury et al., 2019; Corradini, 2020a; Crossler et al., 2013; Donalds & Osei-Bryson, 2020; McIlwraith, 2021). Human factors also relate to human-computer interaction theory, which focuses on designing intuitive systems to enhance usability and reduce user errors by creating user-friendly security tools that fit seamlessly into workflows (Norman, 2017). The need to address the individual, organizational, and technological challenges posed by human factors in cybersecurity, as identified by Pollini et al. (2022), along with the recognition of human factors as key to unlocking the human potential in cybersecurity (Desolda et al., 2021a; Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019), underscores the importance of implementing managerial actions to increase cybersecurity. The objective of the study is to identify those managerial actions that enhance cybersecurity by leveraging the role of human factors. Accordingly, the study presents three main contributions. First, it compiles a set of managerial actions that leverage human factors in cybersecurity based on the existing literature. Second, it uses the Delphi method to reach a consensus on the key actions to undertake. Third, the actions that organizations should implement in the future have been ranked and prioritized with the guidance of experts, who recommended tools and best practices that should be adopted to enhance the potential of these managerial actions.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section "Background" provides an analysis of the theoretical background on managerial actions. In Section "Research design", the research design and methodological approach of a Delphi study are described. Section "Results" presents the results and the experts' perceptions regarding the future role of humans in cybersecurity management. Section "Discussion" discusses the contributions of the study. Section "Conclusions and future steps" concludes and offers ideas for future research.

BackgroundHuman factors in cybersecurityThe field of human factors aims to enhance the interaction between individuals and technology. Extensive exploration of human factors has occurred in diverse fields, notably in health and aviation (Wiegmann & Shappell, 2017), with the aviation sector introducing notable frameworks such as “The Dirty Dozen,” proposed by Dupont in 2009 (Dupont, 2009; Wiegmann & Shappell, 2017) and subsequently adopted in other fields such as healthcare (Poller et al., 2020), and cybersecurity (Desolda et al., 2021b).

Focusing on human factors in cybersecurity research, various classifications, ontologies, or simple reflections on which aspects of human character most influence cybersecurity have been proposed over the years. Specifically, a characterization of human factors, including human behavior, is necessary to understand how the actions of users, defenders (IT personnel), and attackers affect cybersecurity risk. A significant contribution comes from Oltramari et al. (2015), who presented the Human Factors Ontology (HUFO) focusing on trust. HUFO categorizes risk characteristics related to human factors, categorizing them into attackers, defenders, and users interacting with computer networks. The goal is to provide a tool for risk assessment and prioritization in cyber operations. In another comprehensive work (Desolda et al., 2021b), the authors conducted a systematic review of the key research on human factors and phishing. They used the well-known Dupont factors as classification categories and describe the misbehavior of individuals concerning phishing phenomena. Another contribution (Gratian et al., 2018) examined how risk-taking preferences, decision-making styles, demographics, and personality traits all influence individual security behaviors regarding securing devices, creating passwords, proactive awareness, and updating.

Finally, an interesting paper by the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors (CIEHF, 2022) compiled a list of risky human behaviors and correlates them with cybersecurity issues and vulnerabilities.

Other contributions have examined the correlation between human characteristics and cybersecurity behavioral intentions, as well as their impact on compliance with cybersecurity procedures. These studies have focused on specific personality traits or types of attacks, such as social engineering. For example, Williams et al. (2018) investigated employees’ susceptibility to phishing attacks and their responses to emails emphasizing authority and urgency. Similarly, Uebelacker and Quiel (2014) examined the role of the big five personality traits in susceptibility to social engineering. Finally, to provide a holistic method of measuring information security awareness, Parsons et al. (2017) developed the HAIS-Q questionnaire, a 63-item instrument assessing seven focus areas, each divided into knowledge, attitude, and behavior. Recently, Pollini et al. (2022) presented a holistic approach integrating the HAIS-Q model by classifying human factors into individual, organizational, and technological. They applied this framework to pilot healthcare organizations to analyze how HF vulnerabilities may impact cybersecurity risks (Bridger, 2018). Human factors in cybersecurity are analyzed from two main perspectives: the human-centric cybersecurity perspective and the socio-technical systems perspective. The human-centric cybersecurity approach places the user at the center of security design and practices (Pawlicka et al., 2022). This concept emphasizes understanding user needs, behaviors, and experiences to create security measures that are not only effective but also user-friendly. By focusing on the human element, organizations can develop systems that encourage secure behaviors and reduce users’ cognitive load (Pinzone et al., 2020). This approach recognizes that technology alone cannot solve cybersecurity challenges. Instead, a deep understanding of human behavior is essential for crafting solutions that engage users and promote active participation in security practices (Warkentin et al., 2016).

Socio-technical systems theory offers a holistic framework for understanding the interplay between social and technical elements in organizations. This approach has led to the conceptualization of cyber socio-technical systems (Colabianchi et al., 2021; Patriarca et al., 2021) and a risk assessment framework that considers individual, organizational, and technological challenges posed by human factors in cybersecurity (Pollini et al., 2022). It argues that effective cybersecurity depends not only on technology but also on the human and organizational context in which these systems function. This theory emphasizes the need for collaborative efforts among technical teams, management, and users to create effective security solutions (Checkland & Scholes, 1999). By acknowledging the complex interactions between people, processes, and technology, socio-technical systems theory enriches the understanding of human factors in cybersecurity. It promoted a comprehensive approach to designing security systems that accommodate human behavior while addressing technical vulnerabilities (Malatji et al., 2019).

Several theories, including behavioral security and human-computer interaction theories, are crucial for understanding human factors. The behavioral security theory explores psychological and social influences on individuals’ security-related behaviors. It aims to identify the motivations, attitudes, and decision-making processes that drive user behavior in cybersecurity contexts. For example, risk perception and social norms affect how individuals respond to security measures (Herath & Rao, 2009). By applying insights from behavioral security theory, organizations can develop targeted interventions that encourage positive security behaviors, such as adherence to password policies or timely reporting of phishing attempts. This understanding is critical to fostering a culture of proactive security within organizations (Corradini, 2020b).

Human-computer interaction theory examines how people interact with computers and technology. It focuses on designing interfaces that enhance usability and user experience. In cybersecurity, human-computer interaction principles can guide the creation of intuitive security systems that reduce user error and improve compliance with security protocols (Carroll, 1997). Effective human-computer interaction design considers factors such as cognitive load, user feedback, and the overall user journey, ensuring that security measures are seamlessly integrated into users’ workflows (Norman, 2017).

Managerial actions to improve cybersecurity by enabling the positive role of human factorsAccording to the above-mentioned theories, the role of human factors in cybersecurity can be either negative or positive, depending on various aspects. Based on a combination of knowledge, attitude, and behavior (Parsons et al., 2017), people can either pose a threat or contribute to cybersecurity solutions (Desolda et al., 2021b; Ferro et al., 2022). Several actions have been identified in the literature to ensure that human factors play a positive role in enhancing the cybersecurity of the organization. To provide a complete understanding of these managerial actions, current research on the influence of human factors in cybersecurity, as well as sources describing the impact of one of the “The Dirty Dozen” human factors (i.e., Lack of Communication, Complacency, Lack of Knowledge, Distraction, Fatigue, Lack of Resources, Pressure, Lack of Assertiveness, Stress, Lack of Awareness, Norms) on cybersecurity were analyzed.

Initially, a general search was conducted using the broad terms (1) “human factors” and “cybersecurity,” and (2) “human error” and “cybersecurity.” We then refined our search by individually combining Dupont's factors with the term “cybersecurity” (e.g., “communication” and “cybersecurity” or “complacency” and “cybersecurity”). The bibliographical references provided are not exhaustive but rather serve as a starting point for the Delphi study, establishing a link between human factors and cybersecurity issues. The literature identified actions that can mitigate or improve certain human factors, ultimately benefiting cybersecurity. Table 1 presents the intervention actions, their descriptions, linked human factors, and references. When considering the Dupont human factors, the following actions have been identified:

- •

“Encouraging personal responsibility” can mitigate Complacency by increasing Knowledge;

- •

“Reducing cognitive fatigue” can mitigate Fatigue, Pressure, and Stress, and allow better usage of Resources and Norms;

- •

“Workload balance” can help reduce Distraction, Fatigue, Pressure, and Stress, and ensure better allocation of Resources;

- •

“Adopting models and standards” can allow better organizational Resource management;

- •

“Awareness campaigns” can increase the level of Awareness and the understanding of Norms;

- •

“Cybersecurity training” can increase Knowledge, Communication, and the understanding of Norms;

- •

“Dedicating staff to cybersecurity training” can raise Awareness and allow better Resource allocation;

- •

“Defining roles and responsibilities” can have a critical role in Communication;

- •

“Developing a cybersecurity-oriented culture” can improve Communication, Knowledge, Teamwork, and Awareness;

- •

“Encouraging feedback and peer learning” can improve Communication, Knowledge, Teamwork, and Awareness;

- •

“Scheduling cybersecurity activities” can increase Knowledge;

- •

“Sharing success stories” can have a positive effect on Communication, Awareness, and Knowledge;

- •

“Simplifying procedures” may result in working with a lower level of Pressure and Stress;

- •

“Team-level cybersecurity management” can have a positive effect on many factors including Communication, Knowledge, Teamwork, Stress, and Assertiveness;

- •

“Adequacy of technical resources” can improve the management of all the organizational Resources;

- •

“Incident reporting” can improve Communication and Teamwork;

- •

“Remote work cybersecurity” can mitigate Distraction;

- •

“Simulation of cyber incidents” can mitigate Complacency by increasing Knowledge and Awareness;

- •

“Understanding the limitations of cybersecurity devices” can mitigate Distraction and Complacency by increasing Knowledge.

Managerial actions.

| Managerial actions description | Human Factors involved | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| A1. Encouraging personal responsibilityThis action addresses the tendency of individuals to feel insecure and avoid engaging in cybersecurity procedures. Individuals often rely on devices or people, mistakenly believing that these are the sole responsible for system security. Increasing awareness of individual responsibility in cybersecurity is critical to promoting a proactive approach to protecting corporate data and systems. | Complacency; Knowledge | (Fard Bahreini et al., 2023; Henshel et al., 2015; Nwankpa & Datta, 2023) |

| A2. Reducing cognitive fatigue:Cognitive fatigue represents the maximum number of cognitive resources an individual can devote to security issues. Multiple policies and procedures can cause fatigue in employees who may feel stressed and exhausted due to excessive pressure and oversight in the workplace. Cognitive fatigue and associated cyber risks can be mitigated by properly balancing the number of norms when they are brought to the attention of employees (e.g., password changes). | Fatigue; Norms; Pressure; Resource; Stress | (Chowdhury et al., 2022; Corradini, 2020a; D'Arcy et al., 2009; Majumdar & Ramteke, 2022; Nobles, 2022; Nthala & Flechais, 2017; Reeves et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2012; Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019) |

| A3. Workload balance:The importance of workload management and effective scheduling of activities is emphasized to improve organizational cybersecurity. In situations of high mental stress or intense workload, employees are more likely to make mistakes due to distraction. Therefore, it is essential to balance workloads and plan activities wisely to ensure a more secure organizational environment. | Distraction; Fatigue; Pressure; Resource; Stress | (Chowdhury et al., 2022; Dekker & Hollnagel, 2004; Nobles, 2022; Nthala & Flechais, 2017; Wang et al., 2012) |

| A4. Adopting models and standards:The adoption and sharing of certain tools, such as recognized cybersecurity management frameworks and standards, will enable the organization to guide and manage its resources. | Resource | (Sarker, 2023; Taherdoost, 2022; Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019) |

| A5. Awareness campaigns:Awareness campaigns contribute to effective cybersecurity by making people aware of the risks involved. In addition, these campaigns explain the rationale behind the policies, procedures, and practices in place. They may include informational materials, workshops, and specialized training. | Awareness; Norms | (Mailloux et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2022; Young et al., 2018) |

| A6. Cybersecurity training:Training increases knowledge for more effective cybersecurity. Employees, when trained, can be the main driver of more effective cybersecurity. Innovative approaches to training (e.g., VR, games, chatbots) were found to be slightly more effective in raising cybersecurity awareness. | Communication; Knowledge; Norms | (Akter et al., 2022; Kruger & Kearney, 2006; Mailloux et al., 2019; McIlwraith, 2021; Olivares Rojas et al., 2022; Triplett, 2022) |

| A7. Dedicating staff to cybersecurity training:Most organizations suffer from a lack of staff dedicated to cybersecurity awareness programs. Resources responsible for awareness programs are often involved in other activities and areas, which limits their ability to fully commit to employee training. | Awareness; Resource | (Alahmari & Duncan, 2020; Chowdhury et al., 2019; Kompaso & Sridevi, 2010) |

| A8. Defining roles and responsibilities:It is essential to define the roles and responsibilities of each employee, regardless of their areas of expertise, in cybersecurity plans and policies. This process includes the assignment and explanation of the required tasks, functions, and activities. | Communication | (Yukl, 2013) |

| A9. Developing a cybersecurity-oriented culture:Developing a cybersecurity-oriented organizational culture involves the sharing of strategic goals and the communication of cybersecurity standards by linking them to corporate strategy. | Awareness; Communication; Knowledge; Teamwork | (Röcker, 2012) |

| A10. Encouraging feedback and peer learning:In the context of cybersecurity, fostering a culture of feedback and peer learning is critical to creating a secure business environment. This exchange of mutual assessments can help to quickly address a cyber threat and establish a culture of security awareness among all employees. | Awareness; Communication; Knowledge; Teamwork | (Kompaso & Sridevi, 2010) |

| A11. Scheduling cybersecurity activities:Organizations that adopt multiple IT applications and devices do not often include specific cybersecurity training associated with them. Scheduling time for this activity will make the use of these devices more effective and secure. | Knowledge | (European Union Agency for Network and Information Security, 2018) |

| A12. Sharing success stories:The term "success stories" identifies those events where cybersecurity information sharing has made a significant difference. These include situations where participants prevented harm by sharing incident reports and information on previous attacks. Promoting and communicating such "success stories" means recognizing those employees who identify potential attacks and/or report them to colleagues. | Awareness; Communication; Knowledge | (NIST, 2018) |

| A13. Simplifying procedures:Security policies and procedures are often filled with technical language and information that can be difficult to understand. This complexity requires employees to invest time and effort into becoming familiar with these policies. Simplified communication of these procedures by the organization may reduce the burden on employees and improve the effectiveness of the policies themselves. | Pressure; Stress | (D'Arcy et al., 2009; Gale et al., 2022; Proudfoot et al., 2024) |

| A14. Team-level cybersecurity management:Aligning cybersecurity objectives at team level is crucial. A stronger team culture is suggested, where cybersecurity-related Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are defined, incidents and difficulties communicated and cybersecurity is integrated into daily team activities. | Assertiveness; Communication; Knowledge; Stress; Teamwork | (Bao et al., 2016; Bassanino et al., 2014; Cavanaugh et al., 2000; Kompaso & Sridevi, 2010; Pinzone et al., 2020; Rogers & Ashforth, 2017; Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019) |

| A15. Adequacy of technical resources:It is essential that the organization takes responsibility for ensuring that staff have access to all the information, financial and material resources needed to do their jobs. In the context of cybersecurity, this includes maintaining all systems to ensure effective defense against cyber-attacks. The availability of adequate technical resources and their proper allocation and maintenance are critical to enabling individuals to maintain a sound cybersecurity posture. | Resource | (Alahmari & Duncan, 2020; Chowdhury et al., 2019; Kompaso & Sridevi, 2010; Zarreh et al., 2019) |

| A16. Incident reporting:An organization's cybersecurity can be significantly improved by changing the perspective on incident reporting, viewing it as a virtuous act rather than a source of shame for causing the incident. Creating an environment where incident reporting is encouraged and treated confidentially can help identify and mitigate vulnerabilities, thereby protecting the organization from potentially greater harm. | Communication; Teamwork | (Kompaso & Sridevi, 2010) |

| A17. Remote work cybersecurity:The proliferation of remote working requires organizations to rethink their training programs. In particular, companies need to supplement cybersecurity training with procedures specific to remote work. | Distraction | (Bergefurt et al., 2021; Miarmi & DeBono, 2007) |

| A18. Simulation of cyber incidents:People's lack of attention to cyber threats is often due to a lack of direct experience of significant cyber incidents that have disrupted critical services. A training process that provides employees with direct experience or that simulates a cyber-attack may improve skills and raise awareness. | Awareness; Complacency; Knowledge | (Akter et al., 2022; Frey, 2018; Jalali et al., 2019; Maalem Lahcen et al., 2020) |

| A19. Understanding the limitations of cybersecurity devices:A lack of understanding of cybersecurity devices leads individuals to overestimate the effectiveness of these devices in providing complete protection and to overlook the need for human oversight. Improving the understanding of such devices will contribute to more effective cybersecurity management and active oversight. | Distraction; Complacency; Knowledge | (Fard Bahreini et al., 2023; Henshel et al., 2015; Nwankpa & Datta, 2023) |

The Delphi approach was employed to validate the managerial actions needed to enhance the human role in cybersecurity management and to prioritize them based on resource investment. This method provides a systematic way to assess alternative future perspectives and collect reliable data for scientific purposes based on the experts' views. Since its first appearance, the Delphi approach has undergone numerous revisions. It has been adapted not only to align with the nature and objectives of the research but also to meet specific goals, such as shortening the process and ensuring participant involvement throughout the rounds (Yusuwan et al., 2021). Despite some variations, the main characteristics of the Delphi method are consensual, including expert anonymity, controlled feedback, and repeated interactions. Typically, two to four rounds are required to reach a consensus (Avella, 2016; Chang et al., 2020; Demlehner et al., 2021).

Fig. 1 presents an overview of the Delphi method and research design adopted in this study. Specifically, a version of the Delphi method also known as the modified or hybrid Delphi method was adopted (Avella, 2016; Disconzi & Saurin, 2022; Landeta et al., 2011; Luoma et al., 2022). Unlike the traditional Delphi technique, the modified Delphi method does not rely on the expert panel to generate an initial response. Instead, the researcher first compiles responses from various sources, such as a comprehensive literature review, to develop a preliminary set of statements. This curated list is then provided to the expert panel at the start of the Delphi process (Avella, 2016). This approach reduces the cognitive load on experts during the initial phase while ensuring that the content reviewed is grounded in existing evidence and theory. While maintaining the flexibility of the traditional Delphi method by allowing experts to add, remove, or amend statements, the modified Delphi approach enhances the efficiency of the consensus-building process and ensures that the initial framework is comprehensive and research-based. Previous studies have used the Delphi method similarly. Nayak et al. (2021) designed a questionnaire to identify organizational factors influencing competitive advantage in health insurance firms, integrating them with structured interviews. Sillman et al. (2023) identified transaction factors in the Finnish energy systems through a workshop instead of asking open-ended questions to panelists, while the researchers in the work by Berbel-Vera et al. (2022) proposed their initial conceptualization of statements related to key Chief Digital Office functions and then had them validated with support from literature and workshops. Luoma et al. (2022) proposed the first-round questionnaire based on a systematic review of the literature on the role of data in the circular economy, whereas Disconzi and Saurin (2022) started with a literature review of human factors to collect the principles of design for resilient performance. Similarly, the Delphi method has been used in further studies for the identification of human factors (Foster et al., 2020; Kelly et al., 2023). Nowadays, areas such as IT & cybersecurity increasingly require careful planning for a future that integrates research and organizations (Chowdhury et al., 2022).

Research Design adapted from Kluge et al. (2020), Luoma et al. (2022), Schmalz et al. (2021).

In the following paragraphs, each stage of the research design is detailed.

Development of future projectionsThe conceptual background described in Section "Background" and the hypothetical statements for the First round questionnaire instrument were developed based on a systematic review of the literature on the role of humans in cybersecurity. This review was supplemented by recent research on human factors in cybersecurity and analyses of recent cyber incidents. The identified dimensions were integrated into the questionnaire items, which were formulated as statements for estimation tasks. A draft of the projections and questionnaire was then prepared. To ensure relevance, coverage, and a reasonable number of items, the wording was refined through an iterative process with the research group and pilot respondents during a pilot test (Rowe & Wright, 2001). The final questionnaire (Appendix A) for the First round of the Delphi process consisted of 19 statements, each offering the opportunity to recommend tools and best practices for future implementation, two open-ended questions, and a series of questions designed to profile the respondents.

Selection of panelistsThe Delphi method facilitates meaningful assessments and predictions about potential future developments by experts (Tiberius et al., 2022). Therefore, selecting knowledgeable, experienced experts willing to participate throughout the study and able to articulate their views effectively is crucial (Disconzi & Saurin, 2022). Based on these premises, the experts were invited according to the following criteria:

- (i)

scholars specializing in cybersecurity, particularly those interested in human factors and vulnerabilities, who have published at least one article in peer-reviewed journals on these topics. Their expertise was verified using Scopus, a leading academic database with over 90 million records across 29,000 journals, sourced from more than 7000 publishers (RELX, 2023);

- (ii)

practitioners working in areas such as risk management, IT systems, human resources, and business management, who have been involved in at least one cybersecurity-related project (e.g., cybersecurity training for employees). These individuals were identified using LinkedIn, a prominent professional networking platform (Iqbal & Ahmad, 2019). While years of cybersecurity experience were not a primary criterion, all experts were required to have at least three years of general experience, either in research or practice. This minimum experience requirement recognizes the evolving nature of the field and the value of recent entrants' perspectives. These experts were contacted via email.

All selected experts were invited to complete the First round of the questionnaire online. To clarify the study's objectives, all participants were provided with an introduction to the Delphi technique and the research objectives. The introduction can be found in Appendix A. Following the introduction, the experts rated all 19 statements quantitatively based on the perceived importance of the interventions. In addition, for each statement and using an open-ended question, the participants were asked to indicate any personal experiences, tools, and best practices that can be used to implement each specific action. Finally, some open-ended questions allowed the participants to suggest additional actions that they felt had not been addressed by the 19 suggested statements.

An interim analysis followed the execution of the First round of the questionnaire, summarizing and aggregating the responses, for example, by identifying common new actions. The summarized responses were then reported back to the First round participants, along with an invitation to participate in the Second round of the questionnaire. This Second round included only the questions that had not reached consensus previously. For each of these questions, participants were provided with feedback on the group's mean responses, standard deviation, and median, as detailed in Appendix B. This feedback allowed participants to see how the overall group responses were distributed over each specific action, providing context for further evaluation. Participants also received a report containing both quantitative and qualitative results from the First round, including information on the statements that had reached a consensus. Studies have shown that informing participants about the aggregated opinions of others can improve the decision quality of the Delphi method (Berbel-Vera et al., 2022). They were then asked to score the importance of the actions using the same Likert scale.

Analysis of resultsThe analysis of the results began with a descriptive analysis of the responses collected, followed by an identification of those managerial actions that the experts had prioritized. As mentioned for quantitative analysis, the questions focused on the level of importance per action and the suggestions of best practices and tools. In line with previous studies (Berbel-Vera et al., 2022; Yusuwan et al., 2021), in each statement the respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they felt investing resources was important for the future on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not Important) to 5 (Very Important). The mean, together with standard deviation analysis, was used to determine a priority system for the intervention actions. The interquartile range was used as an indicator of consistency, with a threshold calculated based on the number of levels of the Likert scale. To calculate the threshold, the approach proposed by Tiberius et al. (2022), which consists of multiplying the number of Likert scale levels by 0.25, was followed. Thus, for a 5-point Likert scale, 25 % of 5 is equal to 1.25. If the interquartile range exceeds this threshold, it indicates a lack of agreement on that item and, conversely, disagreement. The panel consensus was then assessed. The degree of consensus and degree of convergence were calculated through Eqs. (1) and (2), where Q1 and Q3 are the first quartiles and the third quartile coefficients, respectively.

To judge the agreement among the experts, a degree of consensus greater than 75 % and a degree of convergence lower than 50 % was considered (Berbel-Vera et al., 2022). Furthermore, a two-round process was defined to reach a consensus, in line with the suggestion by Mullen (2003) that no more than two rounds may be necessary when the sample is small. However, for further completeness, the content validity ratio (CVR) developed by Lawshe (1975) was calculated. The CVR is defined as the degree to which a sample of items taken together constitutes an adequate operational definition of a construct (Chang et al., 2020). The CVR was calculated according to Eq. (3), where N refers to the total number of experts and ne refers to the number of experts who indicate that the item is essential (experts who selected “4 points” or “5 points”).

A CVR value greater than zero indicates that more than 50 % of the panel members have agreed that an item is essential. However, according to Lawshe (1975), it is important to define a CVRcritical to be used in the research. In this study, the number of experts was 29, which resulted in a CVRcritical of 0.33.

Finally, the qualitative responses related to the formulation of tools and best practices shared by the experts were analyzed.

Managerial insightsIn this last phase, the values for the managerial actions, as well as the new actions proposed by the experts, are discussed, and theoretical implications are derived. Moreover a cross-analysis of the tools and proposed best practices leads to the identification of practical implications to guide organizations in managing cybersecurity and to support them in their decision-making processes and in the future path of integrating people, processes, and technologies in cybersecurity.

ResultsThis section presents the results of the First and Second rounds of the Delphi study. Two rounds were considered sufficient to reach consensus, in line with previous studies involving small sample sizes as discussed in Section "Analysis of results". The presentation of results begins with an overview of the First Delphi round, outlining the composition of the expert panel and summarizing the initial findings. In this phase, consensus was achieved on 12 statements. Subsequently, the outcomes of the Second round are detailed, where consensus was reached on an additional five statements, while two statements remained without consensus. The final section (Section "Consensus on managerial actions") presents the experts' opinions on implementing the interventions, including the dissemination of tools and best practices for advancing cybersecurity management.

Descriptive statistics of participantsA total of 30 experts were invited to the initial round, with 29 submitting their responses. The Second round questionnaire was sent to these 29 respondents, and 26 participated in this subsequent phase of the Delphi process. Table 2 details the panelists' backgrounds as reported in the First round. The panel was composed of senior professors in the field of information security, researchers in the same field, experienced managers, and other personnel with industrial work experience covering organizational, IT, or risk management roles. The experts interviewed are part of international professional and academic networks operating across both the private and public sectors. While all the experts were based in Italy, the organizations involved in the study were also primarily Italian, but a few cases included Spanish, American, Swiss, and British companies. As for the other variables, there were 23 male and 6 female experts. The age range of the experts was evenly spread between 26 and 62 years. Nearly 70 % of the experts had been working for more than 10 years, with at least six years’ experience in cybersecurity.

Panel demographics.

| Characteristics | N = 29 | |

|---|---|---|

| n | % | |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 6 | 21 % |

| Male | 23 | 79 % |

| Age | ||

| Under 30 | 6 | 21 % |

| 30–39 | 9 | 31 % |

| 40–49 | 5 | 17 % |

| 50–59 | 7 | 24 % |

| Over 60 | 2 | 7 % |

| Work experience | ||

| Less than 5 years | 5 | 17 % |

| 5–9 years | 4 | 14 % |

| 10–19 years | 9 | 31 % |

| More than 20 years | 11 | 38 % |

| Cybersecurity experience | ||

| Less than 5 years | 3 | 10 % |

| 5–9 years | 13 | 45 % |

| 10–19 years | 7 | 24 % |

| More than 20 years | 6 | 21 % |

| Industry | ||

| Academia | 3 | 10 % |

| Banking, and Insurance | 3 | 10 % |

| Chemistry & Pharmaceuticals | 1 | 3 % |

| Consultancy | 1 | 3 % |

| Oil & Gas | 1 | 3 % |

| Transportation | 3 | 10 % |

| Information Technology | 9 | 31 % |

| Logistics | 1 | 3 % |

| Media & Entertainment | 1 | 3 % |

| Social Security | 4 | 14 % |

| Public Administration & Defense | 2 | 7 % |

| Area of Expertise* | ||

| Business Strategy | 5 | – |

| Information Technology | 10 | – |

| Operations Management | 4 | – |

| Cybersecurity | 11 | – |

| Risk management | 5 | – |

| Business size | ||

| Micro (less than 10 employees) | 3 | 10 % |

| Small (10 to 49 employees) | 1 | 3 % |

| Medium (50 to 249 employees) | 2 | 7 % |

| Large (at least 250 employees) | 23 | 79 % |

| Job Title | ||

| Chief Executive Officer | 1 | 3 % |

| Chief Information Officer / Chief Technology Officer / Chief Information Security Officer | 5 | 17 % |

| Cybersecurity / IT / Operations / Digital Strategy Manager | 8 | 28 % |

| Cybersecurity / System / Risk Senior Consultant | 3 | 10 % |

| Cybersecurity Junior Consultant / IT Junior Consultant | 2 | 7 % |

| Cybersecurity Engineer / Cyber Threat Analyst / Cybersecurity Penetration Tester | 6 | 21 % |

| Cybersecurity Professor | 1 | 3 % |

| Software and Systems Security / Visual Analytics for Cyber Security / Cybersecurity Researcher | 3 | 10 % |

Data analysis was conducted using values of the average, median, standard deviation, CVR, as well as the calculated change in these values between Round 1 and Round 2.

The First round was completed in 20 days (from December 11th to December 31st 2023). Consensus of agreement was reached on 12 statements (see Table 3). Specifically, 75 % of our experts agreed on 12 out of 19 statements. No consensus of disagreement was obtained. As noted earlier, comparisons between degrees of convergence, consensus, and critical CVR were made to assess the level of agreement. These analyses indicated that seven statements did not reach consensus, necessitating a second round. Furthermore, the experts reported that two statements overlapped. The expert panel suggested merging Statements 2 and 3 into one because they address both reducing cognitive fatigue and improving workload balance. They also suggested combining Statements 6 and 18 into one category because the latter is considered an instrument of the former. Finally, the experts proposed a new statement called “Responsible use of personal social network,” scheduled for evaluation in the Second round.

Round 1 results.

The Second round was completed in 15 days, from February 12 to 26, 2024. Consensus was reached on five out of seven remaining statements (see Table 4). Therefore, overall, the study achieved consensus on 16 statements. Additionally, the experts agreed that the statement “Sharing success stories” was not essential. The action received a low score of importance and did not reach a consensus. As for “Dedicating staff to cybersecurity training,” the experts did not reach a consensus, but their answers were sparse, reporting a greater interquartile range.

Round 2 results.

Finally, Table 5 displays the statements that have achieved consensus, listed in order of importance. For each action, the best practices and tools suggested by the experts in the open-ended responses that are useful for the dissemination of these interventions are shown in the right column.

Tools and best practices suggested by experts for each action.

Encouraging personal responsibility is an important driver to improve cybersecurity by promoting a culture of vigilance together with proactive engagement in safeguarding it. Several practices and tools identified in the Delphi study can be leveraged to introduce these principles. A primary focus should be on implementing fear mitigation practices, which entails avoiding disciplinary methods following incidents that may breed resentment or foster disengagement. Instead, incentivizing incident reporting with rewards can encourage proactive engagement in sharing essential information. Practical training initiatives such as phishing simulations, and the introduction of gamified approaches, including competitions and gaming elements, are recommended. These methods inject dynamism and motivation into cybersecurity awareness efforts. Specifically, phishing attack simulations emerged as prominent strategies for enhancing preparedness and responsiveness without prior warning. Moreover, cybersecurity must not be viewed as a mere obligation but rather as a golden opportunity for personal and organizational growth, integrating mandatory training with spontaneous practice tests. A multifaceted approach encompassing education, simulation, gamification, and incentivization is recommended to encourage personal responsibility for cybersecurity.

Workload balanceBecause the effectiveness of security practices depends on their integration with user workflows, several practices are suggested. One prominent approach involves aligning cybersecurity protocols with user convenience, exemplified by the adoption of biometric authentication as a user-friendly alternative to complex password requirements. Initiatives such as pre-alerting password change requests and the incorporation of physical device authentication help achieve a balance between security and usability. Additionally, centralizing strong authentication mechanisms and implementing Privileged Account Management simplifies security practices while ensuring robust protection of sensitive assets. Role-specific security standards, including differentiated approaches for top management and general staff, further contribute to workload balance by tailoring security measures to individual roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, the automation of vulnerability management processes and the implementation of specialized human resources reduce the burden on individual users while strengthening organizational defenses. Effective scheduling and workload distribution, facilitated by collaboration between IT departments and other managerial stakeholders, ensure that cybersecurity activities are integrated into existing workflows, as “effective planning reduces mental stress and heavy workloads (as a consequence of workload balancing) on one hand, and on the other, it tends to mitigate cyber risks (stemming from high mental stress situations)” (cybersecurity manager). In essence, the use of automation and a wise allocation of security measures emphasize the importance of harmonizing security measures with user workflows to achieve optimal cybersecurity outcomes.

Adopting models and standardsCybersecurity models and standards represent desirable actions for effective cybersecurity management. These tools include community-developed websites such as OWASP and CWE for software development and vulnerability identification, respectively, and internationally recognized standards such as ISO 27001 for cybersecurity management systems. Additionally, the experts highlighted the role of AI technologies such as Darktrace in enhancing security. Moreover, frameworks such as COBIT were emphasized for their effectiveness in managing cybersecurity risks. Next-generation antivirus solutions, along with endpoint detection and response systems, were identified as essential for proactive threat detection and mitigation. Overall, the consensus among respondents emphasizes the importance of adhering to established standards, leveraging advanced technologies, and implementing robust management systems to bolster cybersecurity posture. However, as a cybersecurity researcher stated, "I believe model and standards adoption is important, but only in cases where the right standard is applied to the right context.”

Awareness campaignsAwareness campaigns represent another effective means to improve organizational cybersecurity. Owing to the ineffectiveness of universal approaches, the experts recommended tailoring awareness campaigns to specific target audiences. Moreover, the experts advocated for mandatory training with final tests to ensure comprehension, alongside interactive sessions such as tabletop exercises and simulations, which should leverage tools such as visors for enhanced engagement. Internal communications, including videos and group challenges, are recommended to reinforce cybersecurity messages. Additionally, specialized professional training is deemed essential to boost employee confidence and enthusiasm. Real-world anecdotes about phishing tools and procedures are recommended, with dedicated sessions led by experienced speakers to captivate the audience. Hence, the need for ongoing or permanent campaigns has been emphasized, and the experts agreed that the more these campaigns engage participants, the greater their impact.

Cybersecurity trainingThe experts provided valuable insights into effective tools and best practices for cybersecurity training, emphasizing the importance of authentic engagement and interaction as opposed to mere obligation. Interactive experiences such as escape rooms, simulations, phishing campaigns, and gaming activities were suggested as particularly effective methods for cybersecurity education. The participants noted that ongoing training efforts within organizations were producing substantial improvements in user attitude toward cybersecurity. They emphasized the need for training to be engaging, contextualized, and applicable outside the workplace. As a cyber threat analyst stated, "the important thing is interactivity—something that truly engages personnel in a defense mindset and creates ‘suspicion’ in everyday activities that could conceal malicious actions.” Role-playing games have been suggested to educate employees on proper responses to cyberattacks, underscoring the interactive nature of effective training. Crisis management exercises, capture-the-flag competitions, and interactive simulations were recommended to enhance cybersecurity awareness and preparedness. Innovative approaches such as cartoons and interactive platforms were noted to improve training effectiveness, even though practical constraints such as budget and time must be considered. Participants agreed that these innovative approaches are more effective than traditional methods.

Additionally, the participants stressed the importance of frequent, in-person training sessions to ensure employee attention and information retention, cautioning against over-reliance on virtual tools such as VR, games, and chatbots. Red Teaming, penetration tests, tabletop exercises, and phishing simulations were highlighted as valuable contributions to cybersecurity training, emphasizing the importance of hands-on practice and real-world scenarios. Overall, the consensus among respondents underscores the need for dynamic, engaging, and interactive training methods to train employees about cybersecurity threats and best practices effectively.

Defining roles and responsibilitiesAccording to the experts, defining roles and responsibilities is another important action to be taken to enhance cybersecurity within organizations. The proposed practices encompass the application of the ISO 27,001 standard at an organizational level, ensuring a structured framework for delineating roles and responsibilities. Dedicated sessions aimed at explaining policies and clarifying defined roles were suggested to facilitate better understanding and adherence. These seminars are designed to establish a clear and shared operational model, fostering a culture of accountability and awareness across the organization. Additionally, periodic simulations of cybersecurity scenarios were recommended to assess individuals' adherence to the roles and responsibilities as outlined in security plans and policies. Importantly, the process of defining roles extends beyond the cybersecurity team to include members of other functions within the organization, emphasizing the importance of cross-functional collaboration in cybersecurity efforts. By presenting case studies of cyberattacks resulting from individual negligence and their repercussions, employees can gain awareness of the cascading effects of lapses in cybersecurity responsibilities. Overall, a standard reference system of roles and responsibilities, combined with ongoing seminars on its understanding and simulations of its implementation, are effective practices for defining roles and responsibilities in cybersecurity management.

Developing a cybersecurity-oriented cultureThe experts agreed that developing a cybersecurity-oriented culture is essential for enhancing overall cybersecurity within organizations. Implementing an Information Security Management System (ISMS) based on the ISO 27,001 standard serves as a foundational step in fostering such a culture, as it provides a structured framework for cybersecurity practices and principles. Additionally, promoting transparency and clarity regarding cybersecurity matters and encouraging a shift towards sharing cyber incident stories with all personnel can significantly contribute to shaping a cybersecurity-focused culture. This entails periodic cyber risk assessments to assess organizational vulnerabilities as well as the endorsement of cybersecurity initiatives by top management through emails and newsletters, which would demonstrate leadership commitment to cybersecurity priorities. Moreover, targeted seminars and specialized professional training, facilitated by external cybersecurity experts, offer employees valuable opportunities to enhance their knowledge and skills, fostering a proactive and informed approach to cybersecurity. Engaging leadership, particularly at the board of directors level, in discussions on cybersecurity strategies and risk management further reinforces the organizational commitment to cybersecurity and cultivates a culture of accountability and vigilance. Through awareness campaigns, training, and ongoing communication efforts, organizations can instill a sense of responsibility for cybersecurity in employees and foster a culture where cybersecurity is integrated into every aspect of operations and decision-making processes.

Encouraging feedback and peer learningEncouraging feedback and peer learning is recognized as a desirable action to enhance cybersecurity within organizations. The respondents suggest implementing evaluation tests with the opportunity for employees to provide suggestions on the improvement of cybersecurity practices. Additionally, facilitating team discussion on cybersecurity best practices allows for peer-to-peer knowledge sharing and learning from common security incidents. Sharing incident stories and providing personalized post-evaluation or post-incident feedback help employees understand the impact of errors and learn from their mistakes, encouraging a culture of responsibility. Importantly, feedback should always be constructive and positive, focusing on actions and incidents rather than blaming individuals. The participants advised against penalizing employees for falling victim to cyberattacks, but recommend encouraging and rewarding the reporting of incidents, which promotes transparency and a proactive cybersecurity mindset across the organization. More specifically, negative feedback should be given constructively and individually, while positive feedback can be shared with the team (or, in special cases, with the organization). As a cybersecurity analyst and penetration tester stated, “it is very important not to condemn the employee who unintentionally facilitated a breach or data leak (provided their innocence has been verified……), but it is equally important to hold them accountable for the future by informing them of how they should have acted. In fact, the way feedback is given in such cases is a very delicate matter.” Overall, practicing open communication, continuous learning, and supportive feedback mechanisms empowers employees to actively contribute to cybersecurity efforts.

Scheduling cybersecurity activitiesThe experts recognized the strategic importance of scheduling cybersecurity activities in the enhancement of cybersecurity within organizations. They advocated for the establishment of a comprehensive process of risk management that encompasses measures such as software design, implementation of security countermeasures, effectiveness monitoring, and vulnerability remediation. Furthermore, they emphasized the necessity of integrating cybersecurity activities into broader organizational strategies, elevating their significance to the level of strategic industrial planning. This entails incorporating cybersecurity education and implementing key frameworks, such as SecOps, for secure development practices. Establishing a Control Tower or Project Management Office (PMO) dedicated to overseeing cybersecurity initiatives ensures centralized supervision and coordination. Penetration testing planning and dedicated calendar blocks for cybersecurity-focused events are also recommended strategies. While acknowledging the challenges posed by the scale of operations in larger organizations, the participants underscored the importance of both targeted education and the exploitation of technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the optimization of resource allocation towards cybersecurity awareness and training efforts. Moreover, it is recognized that “there is a need to include the security-by-design approach in all company processes” (cybersecurity senior consultant and visual analytics for cyber security researcher). By embedding security-by-design principles and limiting employee exposure to unsafe actions, organizations can proactively mitigate risks and foster a culture of cybersecurity awareness and readiness across all levels, making security one of the main drivers in the formulation of a company's architectural, infrastructural, and organizational policies.

Simplifying proceduresThe experts emphasized the importance of simplifying procedures as a strategic action to enhance cybersecurity within organizations. Recognizing that technical jargon and complex language can pose challenges to non-technical personnel, participants advocated for the elimination of anglicisms and the use of clear, concise instructions in the local language, preferably with accompanying illustrative visuals. They stressed the need for specialized training to familiarize employees with the appropriate cybersecurity terminology, alongside dedicated sessions aimed at explaining procedures in an accessible manner. Furthermore, participants recommended incorporating role-playing exercises and simulations of real-life scenarios to provide practical experience in navigating cybersecurity processes. Regular audits and reviews of security procedures are also recommended to identify areas for improvement and streamline governance models. While some caution against oversimplification, emphasizing the importance of precise communication, others underscore the need for user-friendly procedures tailored to the needs of diverse stakeholders. Ultimately, by simplifying procedures and fostering a culture of accessibility and clarity, organizations can empower employees to effectively adhere to cybersecurity protocols, thereby strengthening overall resilience against cyber threats.

Team-level cybersecurity managementTeam-level cybersecurity management is considered a pivotal action for cybersecurity reinforcement. Central to this approach is the adoption and implementation of the ISO 27,001 standard, as it provides a structured framework for information security risks management. Participants advocated for the tailoring of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) to assess the performance and effectiveness of cybersecurity functions at team level. Regular monitoring of these metrics enables teams to track their cybersecurity posture over time, identify areas for improvement, and respond promptly to cyber events. Moreover, the participants emphasized the necessity of ongoing engagement and training initiatives including workshops, seminars, and team-based exercises, to ensure that cybersecurity remains a continual focus for all team members. Dedicated cybersecurity teams or task forces are also recommended to provide specialized support and expertise and to foster a culture of collaboration and reliability. By establishing clear KPIs, implementing escalation procedures for incident response, and fostering a collaborative team environment, organizations can strengthen their cybersecurity resilience and mitigate risks effectively.

Adequacy of technical resourcesThe experts agreed that ensuring the adequacy of technical resources is a key action in the enhancement of cybersecurity. Central to this approach is the implementation of robust security management systems, such as the ISO 27,001 standard, which provides a structured framework for safeguarding information assets. The participants highlighted the importance of leveraging advanced technologies, including AI, to bolster security measures. AI-powered solutions offer the capability to analyze network behavior and detect anomalous activities, enabling timely alerts to security personnel for further investigation and response. Additionally, participants advocated for the establishment of dedicated roles, such as security architects, who should be responsible for the design and maintenance of security infrastructure in collaboration with external analysts from Security Operations Centers (SOC) and Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERT). Meanwhile, the adoption of Secure System Development Life Cycle (SSDLC) principles ensures that security considerations are integrated into all stages of technology deployment and development processes. Technical resources such as AI, antivirus software, and other tools are essential because, without these, personnel would struggle to manage cybersecurity effectively. Merely relying on individual abilities does not suffice: employees also need adequate technical resources and proper training on how to use them.

Incident reportingThe experts underscored the pivotal role of incident reporting in fortifying cybersecurity. They advocated for a multifaceted approach to incident reporting, emphasizing the importance of timely communication and structured documentation throughout the process. A key aspect is the conditionality of incident reporting based on the severity of vulnerabilities or the actual impact of the attack on the system. This nuanced approach ensures that resources are allocated appropriately and critical security threats are addressed effectively. Furthermore, the incorporation of post-incident analysis, such as post-mortem and lessons-learned documents, facilitates continuous improvement and knowledge sharing within the organization. The participants also stressed the importance of confidentiality in incident reporting, ensuring that employees feel empowered to report incidents without fear of repercussions. This entails implementing secure reporting channels and limiting access to sensitive information to authorized personnel only. Additionally, the integration of incident reporting mechanisms with Security Operations Centers (SOC) and Computer Emergency Response Teams (CERT) streamlines response efforts and facilitates collaboration among relevant stakeholders. Regular reporting of incidents, coupled with periodic reviews and revision of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), enables organizations to monitor their cybersecurity posture effectively and refine incident response strategies over time. Ultimately, incident reporting serves as a cornerstone in fostering a proactive cybersecurity culture, promoting transparency, accountability, and collective resilience against evolving cyber threats.

Remote work cybersecurityAccording to our experts, addressing remote work cybersecurity is an action to be undertaken to support the overall cybersecurity posture. The unanticipated widespread adoption of remote work due to the COVID-19 pandemic compelled millions of employees to operate in environments and with tools that might not have always met optimal security standards. While organizations invest in technologies and processes to safeguard their information assets, individuals can apply these measures effectively, which will ultimately make a difference. Key solutions and best practices identified by the participants include implementing stringent system hardening measures, such as VPN with multifactor authentication and USB restrictions, to secure remote connections. Moreover, centralized management of Virtual Desktop Infrastructure (VDI) and enhanced monitoring by Security Operations Centers (SOC) using technologies such as Machine Learning to detect anomalous user behavior contribute to a more secure remote work environment. Mandatory training on cyber vulnerabilities related to remote working along with the requirement for remote access certification highlights the high level of attention organizations dedicate to remote work security. The implementation of Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA) and the utilization of technologies such as Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR), web filtering, and email security further fortify remote work environments. The emphasis on sharing best practices and providing straightforward instructions to users, coupled with the deployment of appropriate remote work technologies, forms a holistic approach to enhancing remote work cybersecurity. By integrating these strategies, organizations can mitigate risks and ensure the security and productivity of remote work arrangements.

Understanding the limitations of cybersecurity devicesThe experts recognized that understanding the limitations of cybersecurity devices is crucial in the enhancement of overall cybersecurity. The widespread adoption of remote work has highlighted the necessity for organizations to deploy robust security measures tailored to the unique challenges of remote environments. While organizations invest in technologies and processes to protect their information assets, stakeholders must comprehend the inherent limitations of these cybersecurity devices. This understanding enables organizations to effectively evaluate the efficacy of existing security measures and identify areas for improvement. Key solutions and best practices identified by the participants include implementing stringent system hardening measures, such as VPN with multifactor authentication and USB restrictions, to secure remote connections. By acknowledging and addressing the limitations of cybersecurity devices, organizations can develop more resilient cybersecurity strategies and prevent employees from over-trusting these devices.

Responsible use of personal social networksThe theme of social networks and cybersecurity is becoming increasingly relevant due to the widespread use of platforms and the growing user base, who begin at a younger age. It is therefore important to incorporate security topics into training and prevention programs to address potential cyberattacks. Implementing rules and templates for whatever can be shared on social networks is crucial. Sensitization (and awareness) campaigns with realistic practical examples are essential to truly convey the devastating impact of cyberattacks. There is often a lack of awareness of the implications of sharing personal information on social networks, especially concerning the security of the organization one works for. Attention should also be given to regulatory aspects, particularly regarding the use of social media in the workplace. Although this may be more relevant for companies with mobile devices operating on corporate VPNs, it is still important to consider the consequences for all companies. Social networks serve as abundant sources of information for conducting attacks such as business email compromise (BEC). Thus, web filtering systems are essential, as evidenced by their inclusion in the 2022 version of ISO27001. As reported by a Chief Information Security Officer, “One of the attacks observed in the past originated directly from LinkedIn, through a fabricated job position and the exchange of a Word document containing an infostealer. However, our XDR solution successfully prevented the execution of the malware, enabling us to reconstruct all events of the attack. Social networks are integral parts of our lives and pose an increasing cyber risk, amplified by the introduction of AI. Corporate training should encompass the risks and behaviors to adopt on these platforms. Several colleagues have highlighted how this training has significantly benefited their personal sphere as well.”

DiscussionAt the end of the Delphi study, the experts reached a consensus on 16 critical managerial actions to be taken to enhance the role of humans in cybersecurity management. This confirms a significant paradigm shift over recent years (Edeh, 2023; Pawlicka et al., 2022; Rahman et al., 2021). The research presents several insights, which can be categorized into theoretical and practical contributions.

Theoretical contributionsThe managerial actions that emerged from the study, qualitatively described in Section "Consensus on managerial actions", contribute to the ongoing debate regarding the role of people in cybersecurity–whether as a source of threat or as solutions to cybersecurity vulnerabilities (Desolda et al., 2021b; Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019). Specifically, the actions aim to enhance cybersecurity by using human factors potential, which addresses the research objective.

Viewed through the lens of socio-technical systems theory (Malatji et al., 2019; Patriarca et al., 2021), and in line with Pollini et al. (2022), the proposed actions are categorized into three perspectives: individual, organizational, and technological.

Therefore, the managerial actions identified contribute to both behavioral security theory and human-computer interaction theory, offering a socio-technical perspective on the actions needed to leverage human factors in improving cybersecurity.

Table 6 outlines the above-mentioned perspectives, the suggested actions, the human factors involved, and the tools and best practices that can facilitate the implementation of the actions.

Managerial actions transforming human factors from threat to opportunity.

The experts offered several takeaways for organizations dealing with emerging cybersecurity issues and agree that practitioners and scholars should view humans as integral solutions to cybersecurity challenges rather than vulnerabilities (Zimmermann & Renaud, 2019). In addition, the experts established a prioritization hierarchy for resource allocation to these interventions, acknowledging the financial and temporal constraints organizations face when implementing effective cybersecurity strategies (Annarelli et al., 2021; Chidukwani et al., 2022). By answering open-ended questions, the participants shared their insights and experiences, highlighting tools and best practices that can help organizations overcome future cybersecurity challenges.

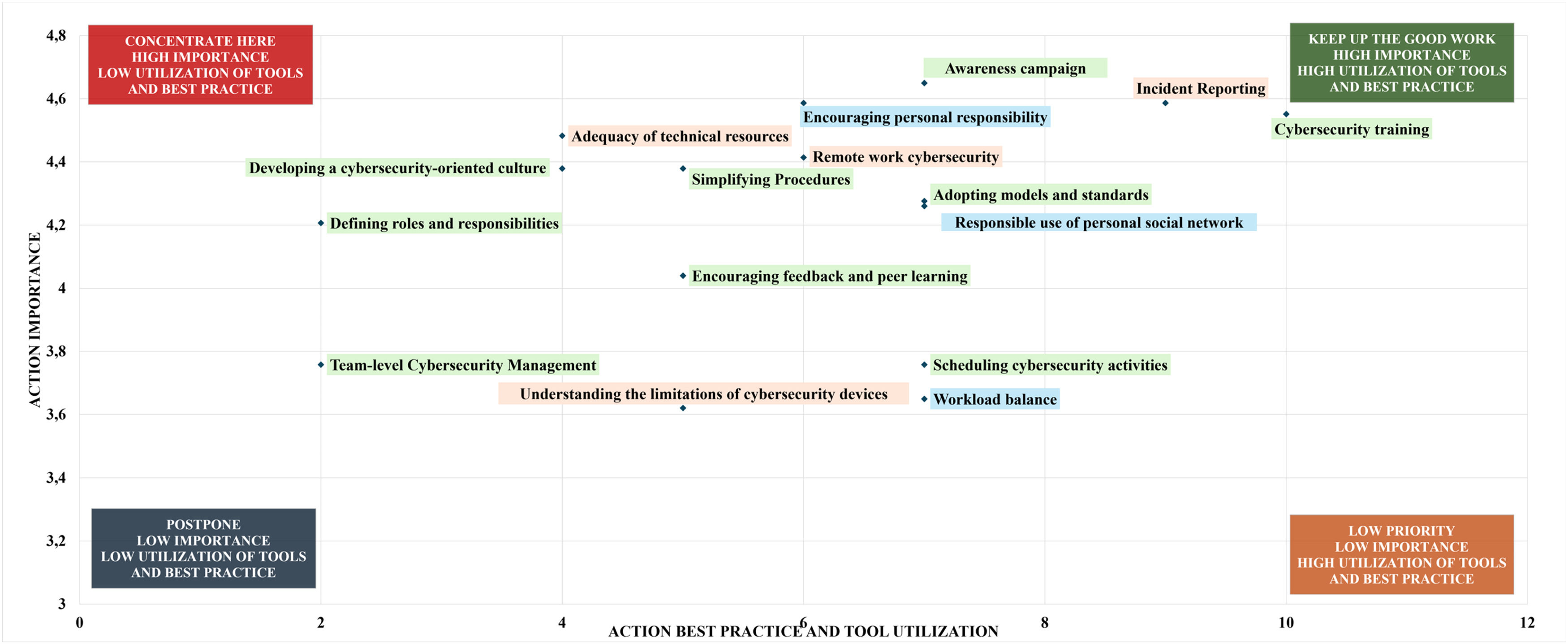

Fig. 2 categorizes these intervention actions based on the urgency of investment (y-axis) and the availability of supporting tools or best practices (x-axis). The y-axis, labeled “Action Importance,” represents the experts’ ratings of each intervention action on a scale of 1 to 5, indicating how critical they consider it to prioritize or invest in the corresponding business objectives. The x-axis, labeled “Action Best Practice and Tool Utilization,” indicates the number of tools and best practices recommended by the experts for each action. A higher value on this axis suggests that these actions are already being extensively addressed and implemented by practitioners through the use of specific tools and best practices. The diagram displays four separate quadrants. The first quadrant, “Concentrate here,” highlights the need for urgent attention to high-priority actions with limited support, such as fostering a cybersecurity-inclusive organizational culture and clarifying cybersecurity roles and responsibilities. These actions have limited tools or best practices available, which makes them a critical focus for the cybersecurity community. The second quadrant, “Keep up the good work,” emphasizes sustaining momentum on actions already supported by effective tools, such as ongoing cybersecurity training and incident reporting mechanisms. Effective tools identified for cybersecurity training include simulation exercises, gaming, role-specific training, tabletop exercises, and competitions (Fig. 2). For incident reporting, the experts suggested tools include lessons learned documents, incident response plans, web portals, post-mortem analysis, and SOC (Security Operations Center) reporting (Appendix C). The framework also identifies lower-priority areas, labeled “Postpone” and “Low Priority,” which may require future investment. These actions encompass team-level cybersecurity management, fostering feedback and peer learning and maintaining workload balance. They are especially crucial for SMEs, where priorities must be carefully managed (Armenia et al., 2021). The framework serves as a strategic guide for both established entities looking to improve their cybersecurity investments and nascent firms navigating initial resource allocation.

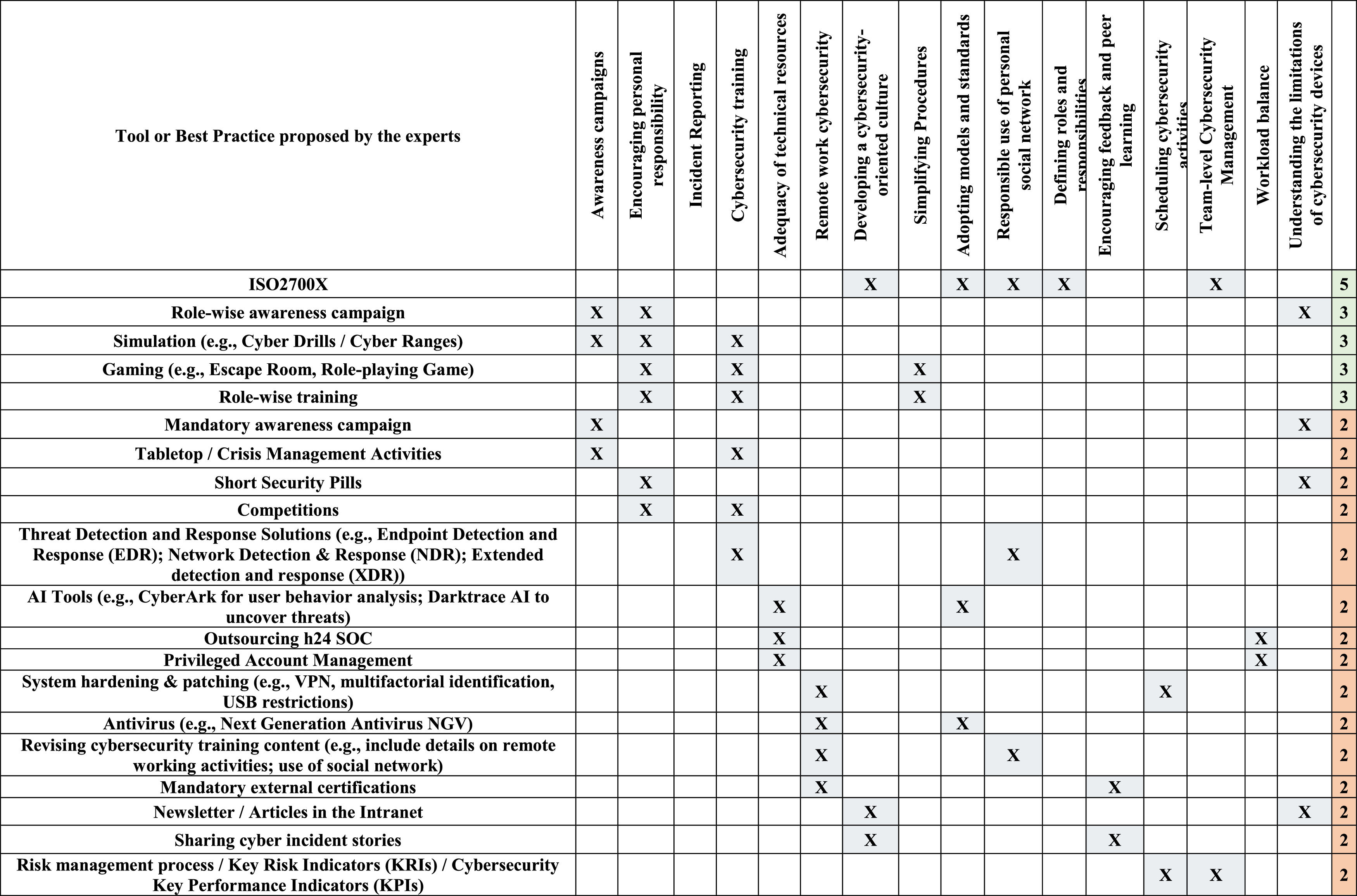

A subsequent visualization, Table 7 (Table 7 is an extraction of the full table (Table C. 1) that can be found in Appendix C) details the 44 tools and 26 best practices identified by the experts, highlighting a balanced approach that goes beyond technical solutions to include mindsets and procedural shifts (Blair et al., 2019; Jeong et al., 2019). Notable examples include the ISO27000 series and innovative engagement methods such as role-wise and skill-specific gamification and simulations, which are effective in fostering a cybersecurity culture. Furthermore, effective knowledge transfer is achieved through role-specific and skill-specific campaigns and training. When addressing complex topics like this, it is essential to engage individuals by tailoring the proposal to their skills (Dincelli & Chengalur-Smith, 2020; Erdogan et al., 2021). Continuous learning is necessary due to the constant emergence of news on cybersecurity, new threats, and attack techniques (Annarelli et al., 2020; Prümmer et al., 2024). Short security training sessions, small-scale training, or periodic communications (e.g., short security pills) are recommended. Moreover, the findings suggest a holistic approach to cybersecurity, advocating for the integration of technology-driven solutions such as AI for behavior analysis and attack detection within a broader framework that prioritizes human-centric strategies and continuous skill development. A comprehensive table of tools and practices (Table C.1) illustrates potential synergies across multiple intervention actions, offering a roadmap for targeted and efficient future investments in cybersecurity.

A practice that emerged from the study is the use of simulation and gamification to drive engagement and facilitate learning. This observation, corroborated by the experts, aligns seamlessly with existing literature. Engagement stands out as a strength of the game and simulation-based training programs, albeit requiring regular updates to address new threats and vulnerabilities, and often targeting specific user groups and roles (Jayakrishnan et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2018; Nagarajan et al., 2012; Sheng et al., 2007; Tonkin et al., 2023). While not groundbreaking, this insight underscores the relevance and contemporary perspective of our experts, demonstrating alignment with current best practices. An innovative practice identified involves the optimal way to provide feedback on cybersecurity, encouraging incident reporting and knowledge sharing. By enabling individuals to report incidents privately, receive feedback individually, and communicate anonymously within the company, it is possible to reduce the stigma associated with being a cybersecurity incident victim. Furthermore, it is possible to incentivize the sharing of positive experiences (e.g., an avoided attack) by collectively giving positive feedback and prizes. These mechanisms induce organization members to collaborate in reporting positive and negative experiences. By means of intra- and inter-company networks, the experiences can be used internally and externally to prevent adverse events and behaviors. Another key insight pertains to the necessity of targeting cybersecurity resources and processes according to specific roles to ensure effectiveness. Simplified language for non-experts, role-specific training, and access to targeted information and technologies can streamline cognitive information processing and mitigate risky behaviors, effectively distributing responsibility. By implementing these strategies, organizations can empower employees to play an active role in cybersecurity and transform threats into opportunities.

Conclusions and future stepsThis research marks a significant advance in understanding the critical role of humans in enhancing cybersecurity management within organizations. The Delphi method facilitated expert consensus on 16 key intervention actions that represent a paradigm shift in the cybersecurity domain. This shift recognizes humans as essential components of cybersecurity solutions, rather than merely as sources of vulnerabilities. The findings underscore the need for a comprehensive, human-centered approach that integrates technological tools with strategic human interventions to foster a robust cybersecurity culture. The analysis presents a prioritized roadmap for organizations to effectively implement human-focused interventions and defend their information systems. It highlights the importance of continuous learning, the development of a cybersecurity-inclusive organizational culture, and the clarification of roles and responsibilities within the cybersecurity framework (Tejay & Mohammed, 2023).

Despite its contributions, this study has certain limitations and offers directions for future research. Increasing the sample size of experts involved in the Delphi study could enhance the robustness of the findings. Moreover, practical assessments are essential to guide companies in implementing the identified intervention strategies effectively. Future research should also focus on developing conceptual frameworks or models that organizations can use to integrate human factors into their cybersecurity strategies efficiently.