This study aims for an in-depth exploration into the effects of digital transformation on firms’ financial performance and how this impact can be measured. The research employs a two-stage method to evaluate firms’ digitalization processes. In the first stage, keywords related to digitalization are extracted from annual reports through text mining, and digital transformation strategies in five different sectors are analyzed. Based on these analyses, the return of digitalization (ROD) ratio is developed to assess the effects of digital transformation. In the second stage, a panel data analysis is conducted to examine the impact of digitalization and the ROD ratio on a firm’s performance. The research findings clearly indicate that digital transformation generates positive effects on firms’ financial performance. It also appears that digitalization provides a competitive advantage, particularly in areas such as operational efficiency and brand value. Firms with a high ROD ratio, which can be used as an indicator of digital transformation investments, demonstrate stronger financial performance. The ROD ratio has emerged as a critical indicator that effectively measures the financial outcomes of digital transformation.

Over the past two decades, digital technologies have made significant advancements, leading to the emergence of various next-generation devices, platforms/infrastructures, and applications. The increasing use of these technologies has transformed many activities in daily life as well as profoundly altering the business world. Digital transformation and the accompanying next-generation technologies have fundamentally changed consumer expectations and behaviors, forcing traditional business practices to adapt. Digitalization has further enhanced the interaction between firms and consumers, making transformation imperative by reshaping the way businesses operate. Today, firms across almost every sector are striving to adopt new digital technologies and leverage their advantages. In this context, firms are introducing new business models, products, and services in an effort to maintain and enhance their competitive edge. Indeed, the United Nations (UN) declared in 2015 that digitization is one of the most critical factors in achieving sustainable development goals (SDGs). The declaration emphasizes that ensuring economic sustainability and solving environmental issues can only be realized through the digital transformation of firms (United Nations, 2024). Furthermore, the World Economic Forum launched the Digital Transformation Initiative in 2015, predicting that digital transformation would contribute $100 trillion to business and society (World Economic Forum, 2024). This initiative aims to encourage existing firms to embrace a transformation based on digital technologies that are reshaping how people live and work. The rapid and widespread adoption of digital transformation philosophies across various sectors has been driven not only by the support of international organizations and public sectors but also by firms’ reflexes to maintain competitive advantages over their rivals (Laffi & Lenzi, 2021). Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data, the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud technologies, metaverse, mobile technologies, social networks, and blockchain, which form the core of the digital transformation philosophy, are highly popular today. Indeed, firms are planning to implement these technologies to bring significant changes to their operations, production processes, and organizational structures.

From a business perspective, digitalization fundamentally refers to the integration of advanced digital technologies into a firm’s operations. Considering the costs and benefits this process brings to a firm, it is expected to result in either positive or negative financial performance outcomes. Firms that undergo a successful transformation process and optimize their production processes to increase efficiency can make a significant step toward improving their financial performance (Wamba et al., 2017). Indeed, several studies in the literature suggest that firms that actively invest in digital technologies tend to perform more effectively in the market and outperform others (Dubey et al., 2019; Yasmin et al., 2020). However, Kohtamäki et al. (2020) point out that digital transformation incurs know-how costs, while Liu et al. (2019) argue that these costs place a significant burden on firms during the transformation process. In particular, firms with less accumulated digital leadership may face difficulties due to these costs, thus negatively impacting their financial performance. As a result, the impact of digitalization on a firm’s performance, whether positive or negative, presents significant uncertainty for businesses. This uncertainty is referred to in the literature as the “digital transformation paradox,” “Solow paradox,” or “productivity paradox” (Solow, 1987; Zeng et al., 2022).

The concept of the productivity paradox refers to the disproportion between investments in digital technologies and productivity growth at the firm level. Indeed, existing studies show that despite intensive investments in digital technologies, firms are unable to achieve the expected level of productivity increase (Posti & Maiti, 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). This proportion highlights a persistent disconnect between the two concepts, commonly referred to as the “productivity paradox” in the literature (Zheng & Dai, 2025). Although firms have attempted to adopt digital technologies intensively in recent years, they have struggled to convert these investments into performance gains. Numerous studies have revealed that this difficulty stems from factors such as in-house knowledge management, organizational incompatibility, leadership competencies, and inadequate process integration (Prakash et al., 2024; Gao et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the productivity paradox remains an unresolved challenge, particularly for firms undergoing digitalization.

Despite the growing volume of research on digital transformation, there remains a significant and underexplored gap in developing firm-level quantitative metrics that can reliably assess digital transformation’s financial impact. Prior studies have predominantly utilized qualitative methodologies, such as surveys, interviews, or case studies (e.g., Kohtamäki et al., 2020; Truant et al., 2021), which, although valuable for capturing managerial perceptions, are inherently limited in terms of scalability, objectivity, and temporal consistency. Furthermore, existing indicators often fail to provide sector-level comparability or longitudinal insights, making it difficult to generalize findings across industries or track performance over time. More importantly, there is a notable lack of computational frameworks that directly connect firms’ digital transformation efforts with their financial outcomes. This methodological shortcoming limits academic understanding and managerial decision-making regarding the return on digital investment.

In this context, there is a growing need for new empirical evidence and more in-depth research on digital transformation. Responding to this need, this study aims to clarify the relationship between digitalization and a firm’s performance, offering a reasonable explanation for the “digital transformation paradox.”

This study introduces the return on digitalization (ROD) ratio, i.e., a novel, computation-based metric that captures the intensity of digital transformation activities embedded in firms’ official disclosures and relates them to financial performance over time. The ROD ratio not only improves upon prior approaches by offering a replicable and scalable measure but also enables cross-sectoral benchmarking and dynamic analysis of digital transformation’s impact. As such, it provides a rigorous empirical tool to bridge the disconnect between firms’ digital strategies and measurable financial outcomes.

This study contributes to the digitalization literature in several ways. First, it presents a new perspective on measuring the extent of a firm’s digitalization. Previous studies have collected data on digitalization through surveys or interviews (De Luca et al., 2021; Kohtamäki et al., 2020; Martínez-Caro et al., 2020; Ribeiro-Navarrete et al., 2021; Truant et al., 2021; Abou-Foul et al., 2021; Stacho et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). However, it is challenging to fully measure the degree of digitalization through surveys alone, as these methods may have limitations in terms of data availability and comprehensiveness. This study primarily seeks to understand what the concept of digitalization means for firms by utilizing text-mining methods, based on their digitalization strategies, intentions, and activities.

The research examines the digital transformation processes of firms operating in the technology, finance, retail, energy, and automotive sectors and assesses the impact of these processes on financial performance. By referencing the digital transformation paradoxes in the literature, we aim to shed light on existing uncertainties and demonstrate how this study can serve as a guide for firms in their strategic decision-making.

In the study, the annual reports periodically published by firms in the five sectors are analyzed through text mining to identify the common understanding of digital transformation among these firms. Based on the findings from this analysis, we aim to develop a measurement approach to understand the impact of the digitalization strategies implemented by these firms on their performance.

The study’s findings will help firms better understand which areas they should focus on when developing their digital transformation strategies and how these strategies affect financial performance. Moreover, by comparing the impact of digital transformation practices across different sectors, the study will contribute to understanding sectoral dynamics and developing sector-specific strategies. In this regard, the research aims to provide firms with the necessary information and analyses to make more effective strategies and decisions during their digital transformation processes.

The manuscript is structured into the following sections: First, the relevant literature is comprehensively reviewed, and the conceptual framework of the study is established. Then, the definition of the ROD ratio and the development of research hypotheses are given. In the following section, the methodological approach to panel data analysis is detailed, and the model used, as well as the diagnostic tests applied, are explained. The empirical findings are then presented, and their meaning is discussed. In the next section, the results obtained are discussed in depth, both theoretically and practically. The study concludes by summarizing the main insights obtained, stating the study’s limitations, and presenting suggestions for future studies.

Theoretical framework: Linking innovation, capabilities, and institutional pressures in digital transformationThis section outlines the theoretical framework guiding the study, grounded in Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction, Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation, and the resource-based view, with a particular focus on dynamic capabilities theory. These perspectives collectively inform the strategic implications of digital transformation.

Creative destruction and disruptive innovationTechnological innovations are one of the fundamental driving forces that set the market economy in motion and keep it dynamic. The market economy not only regulates the prices of goods and services but also continuously transforms industries and firms, creating a cycle by eliminating the old and introducing the new. This cycle is a cornerstone of Schumpeter’s (2013) theory of “creative destruction,” which refers to the disruption and eventual elimination of existing activities by innovative products or services entering the market. In particular, new digital technologies present opportunities to change the rules of the game and existential threats for large and established firms in the industry. Consequently, these firms are investing in new technologies to maintain their competitive edge in digital economies (Galindo-Martín et al., 2019). In recent years, “digitally born” firms like Meta (formerly Facebook), Google, Spotify, and Steam have become successful examples of Schumpeter’s renowned theory.

These examples overlap with Christensen’s (2015) theory of disruptive innovation, which posits that new technologies redefine customer value and bring about radical changes in markets dominated by existing firms. There is an important complementarity between Schumpeter’s concept of creative destruction and Christensen’s theory of disruptive innovation. While Schumpeter explains how technological changes transform economies, Christensen reveals the dynamics and strategic effects of this transformation at the firm level (Gupta et al. 2024). This study frames digital transformation as a strategic opportunity and an existential threat for firms, addressing the intersection of the concept of creative destruction and the theory of disruptive innovation.

Technological milestones of digital transformationWhen digital transformation is examined from a technological perspective, the revolutionary changes in technology over the past fifty years stand out. In the 1970s, computer technology began to develop, enabling the automation of some simple tasks. The invention of the Internet, which made online information-sharing possible, along with the significant advancements in information and communication technologies, were among the most important milestones in the digitalization process (Legner et al., 2017; Heavin & Power, 2018). In the era of Web 3.0, technologies such as social media, mobile phones, analytics, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things (SMACIT) have gained prominence. The current literature projects the use of blockchain (and smart contracts), robotics, artificial intelligence, and cognitive and quantum computing (BRAICQ) technologies as the future trajectory of digitalization (Chanias, 2017; Legner et al., 2017; Vial, 2021; Verhoef et al., 2021; Schwab, 2024).

Digital transformation and firm performance uncertaintyAlthough the literature examines the relationship between digitalization and a firm’s performance within the framework of the digital transformation paradox, to our best knowledge, there is no consensus on the nature of this relationship. While some studies have concluded that digital technologies positively impact firm performance and market value (Huang et al., 2020; Yasmin et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022), other studies argue that investments in digitalization merely impose financial burdens on firms (Ho & Mallick, 2010; Chae et al., 2014). Although significant findings have been obtained regarding the productivity and efficiency gains of digitalization, the overall impact of digital transformation on firm financial performance remains uncertain. One reason for this uncertainty is the ambiguity associated with the digital transformation paradox; another significant factor, however, is the cost of such investments.

McKinsey & Company (2024) found that the firms analyzed in the United States had only digitalized up to 30% of their operations and production processes. Consequently, it was revealed that approximately 70% of these firms’ digital transformation initiatives had failed. The same study highlighted that around 17% of the revenues of these firms were derived from digital products and services. Considering the share of e-commerce revenues in total revenues, the uncertainty surrounding the financial effects of digital transformation is seen as a significant constraint, preventing firms from making swift decisions regarding transformation efforts (McKinsey & Company, 2024). Similarly, Zeng et al. (2022), which examined the digital transformation efforts of more than 16,000 firms operating solely in China, concluded that only 16% of these firms succeeded, meaning that 84% of them failed.

Conceptual ambiguity in the literatureThe fact that nearly 80% of firms attempting digital transformation fail is, in fact, not surprising. Current studies present hundreds of different views regarding the definition, scope, and process of digital transformation. Because debates continue about what digitalization means, what processes it covers, and its scope, this uncertainty makes it challenging to understand digitalization and digital transformation. Vial (2021) analyzed 282 studies focused on digital transformation and identified three main frameworks in which the concept is defined in the literature. The first framework consists of studies that limit digital transformation to the activities firms undertake within their own organizational structures. The second framework relates to studies that link digital transformation to the types of technologies firms invest in. Last, the third framework focuses on studies that directly examine the effects of digital technologies on everyday life and sectors (Vial, 2021).

According to Gong and Ribiere (2021), 134 studies attempted to define the concept of digital transformation were reviewed. The authors found that the studies predominantly focused on strategies and regulations that firms could apply during the transformation process, thus offering various definitions. Indeed, the existing literature reveals no universal or comprehensive definition of digital transformation (Haffke et al., 2016; Morakanyane et al., 2017; Gray & Rumpe, 2017; van Veldhoven & Vanthienen, 2019; Vial, 2021).

Stock and Boyer (2009) emphasized that a concept without a unified definition cannot be developed in theory or practice in the long-term. While agreeing with Stock and Boyer’s (2009) viewpoint, Riedl et al. (2017) argued that scientific progress and the accumulation of cumulative knowledge can be achieved through presenting different perspectives without leading to further complexity (Mertens & Wiener, 2018). As researchers have noted, the complexity of the literature may be a factor that hinders the success of digitalization and digital transformation.

Resource-based view and dynamic capabilitiesThe resource-based view (RBV) states that sustainable competitive advantage stems from firms’ ability to acquire, develop, and effectively use valuable, rare, nonimitable, and nonsubstitutable (VRIN) strategic resources (Barney, 1991; Peteraf, 1993). In order for firms to achieve competitive advantage, they not only have the capabilities in question but also the ability to restructure them in a way that can respond to environmental changes (Teece et al., 1997; Teece, 2018).

In the age of digital transformation, these capabilities emerge as dynamic capabilities such as data integration at the corporate level, organizational agility, adaptable information technology architectures, and organizational learning processes (Teece, 2007; Li et al., 2018; Warner & Wäger, 2019; Chaudhuri et al., 2022).

According to Teece et al., (1997), these capabilities develop in three stages: sensing opportunities in the environment; seizing; and restructuring internal resources (reconfiguring). Existing studies reveal that such intangible dynamic capabilities are not only a supporting element for firms but also fundamental strategic differentiators in markets shaped by digitalization and uncertainty (Li et al., 2018; Warner & Wäger, 2019; Chaudhuri et al., 2022). Recent studies also emphasize that dynamic capabilities play a role in the process of transforming firms’ internal resources (e.g., human capital) into innovative outputs (Ali et al., 2021; Mehralian et al., 2023; Edgar et al., 2024; Tatlı, 2024).

Institutional Theory and Digital TransformationInstitutional theory suggests that firms shape their strategic decisions during the digital transformation process not only by internal dynamics but also by institutional pressures from the external environment. According to this perspective, digital transformation strategies are formed in response to compelling, normative, and imitative pressures, such as regulatory requirements, industry norms, and the actions of competitors (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2008). Firms respond to such environmental expectations by turning to digital transformation initiatives to maintain or strengthen their legitimacy. However, these initiatives may not always reflect a fundamental transformation; in some cases, they may remain at a more symbolic level in order to adapt to the external environment (Meyer & Rowan, 1977).

Recent studies reveal that this transformation process is not only determined by external pressures but also by the interaction among a firm’s internal resources, technological capabilities, organizational routines, and institutional dynamics (Kulp & Mrożewski, 2025; Purnawan, 2025; Poszytek, 2025). In this context, digital transformation is evaluated in two ways within the framework of institutional theory: as a strategic response to environmental legitimacy pressures; and as a response of internal structures to the transformation.

Failure rates and the need for strategic reassessmentFor a firm, financial status acts as a constraint and a driving force. Firms can improve their performance at the end of a successful transformation process. However, the transformation process itself imposes a cost on the firm. Firms that lack the financial resources to cover these costs may find themselves excluded from the transformation process. Additionally, if the transformation is unsuccessful, the expenses incurred during the process may place financial pressure on the firm. Therefore, for a digital transformation strategy to succeed, it is essential to establish independent strategies aligned with the firm’s goals, considering both internal and external factors (Matt et al., 2015; Bican & Brem, 2020; Kim & Kim, 2022).

The approximately 80% failure rate in digital transformation initiatives encountered by firms in the U.S. and China underscores the importance of properly designing a digital transformation strategy. Existing studies frequently focus on firms’ digital transformation efforts, industry-specific characteristics, the challenges of the transformation process, the motivation for transformation, and the causes of failure (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Kane et al., 2015; Hess et al., 2016; Ismail et al., 2017; Tekic & Koroteev, 2019). This situation highlights the surprisingly low performance of the business world in leading digital transformation. Notably, the failures experienced by industry giants such as General Electric, Ford, and Proctor & Gamble (P&G) due to disruptions in their transformation processes serve as significant examples, thus demonstrating the need for a reassessment and redesign of digital transformation strategies (Siebel, 2019).

Current studies address the failures experienced in the digital transformation process from a broader perspective. for example, emphasized the importance of digital leadership in the digital transformation process. Research findings emphasize that companies without chief digital officers (CDOs) are more prone to strategic disorientation, which can disrupt interdepartmental coordination and jeopardize the implementation of targeted strategies within the firm. Poláková-Kersten et al. (2023) further stated that digital transformation failures are generally caused by the rigidity between innovation-oriented change and efforts to preserve corporate identity. Moreover, recent empirical findings also indicate that digital transformation can yield contradictory outcomes for companies (Guo & Xu, 2021; Zhao et al., 2024; Yavuz, 2024). Li et al. (2025) found that, although companies’ digital initiatives can increase economic performance, environmental performance can deteriorate under high market turbulence. In this context, companies should consider the context in which they operate when creating their digital transformation strategies and make informed decisions by questioning the suitability of the strategies they develop for environmental and economic sustainability. Accordingly, current studies indicate that the reason for companies’ digital transformation failures is not solely the result of poor investment decisions or technological immaturity. In addition, factors such as incompatible leadership, institutional inertia, and corporate identity frictions also lead companies to failure. Therefore, it is essential for companies seeking to execute a successful digital transformation process to consider these factors in the strategies they develop.

Methodological frameworkMeasuring digital transformation in firms and data collectionAnnual reports reflect the current business status, trends, and strategies of firms. Therefore, evaluating a firm’s digitalization through text mining is scientifically valid and reasonable (Zeng et al., 2022; Chen & Srinivasan, 2024). In this study, a text-mining method was adopted to extract keywords related to digitalization from the annual reports of firms, and, based on the extraction results, a “digital” keyword pool was created for the firms.

The steps involved in creating the data for the analysis process are as follows.

First, starting from the annual reports of listed firms between 2009 and 2021, all words beginning with the keyword “digital” such as digital assistants, digital application, digital content, digital advertising, digital agenda, digital platform, and digital innovation, which are related to the concept of digitalization, were identified to form the keyword pool. The frequency of their usage in the reports was then measured. Words starting with “digital” that were unrelated to digitalization were excluded from the data set.

Second, all the words in the keyword pool generated from the firms’ annual reports were distributed according to the sectors the firms belong to, and the overlapped or commonly words used across five sectors were identified.

As a result of the research, eight words commonly used across these five sectors are shown in Fig. 1.

Intersecting keywords indicate the areas within a sector where digitalization is most pronounced and where strategic investments are concentrated. For example, if terms like “digital commerce” and “digital advertising” are frequently used in the retail sector, it suggests that this sector places significant importance on digital commerce and advertising strategies. Additionally, these keywords reflect how firms use technology and the potential for this usage to provide a competitive advantage. For instance, if the term “digital after-sales services” is often mentioned in the automotive sector, it indicates that digitalization strategies in customer service and after-sales services are prominent in this sector. This demonstrates the investments made by firms in technology to enhance customer satisfaction and maintain competitiveness in the market. Therefore, examining sectors within a holistic framework will be a crucial point in understanding the business world’s approach to digitalization.

The technology, retail, energy, finance, and automotive sectors addressed in this study represent significant portions of the global economy. Therefore, the eight keywords obtained from annual reports and commonly used, reflecting these sectors’ approaches and trends toward digitalization, will be useful in revealing what the business world understands by the concept of “digital transformation,” in contrast to academic studies. Fig. 2 presents a visual representation of these intersecting eight keywords in terms of their meaning and content.

Examining Fig. 2 reveals that a firm’s understanding of digital transformation is a comprehensive process that extends from digital capabilities through strategic planning and innovative approaches to digital tools, platforms, services, and applications. To better express what sectors understand by digital transformation, the following key elements emerge (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Reis et al., 2018; Vial, 2021):

- •

Digital Capability: The initial step in the digital transformation process for firms is to assess and develop their existing digital capabilities. These capabilities include the skills and knowledge required to use digital technologies.

- •

Digital Strategy: Developing a digital strategy based on digital capabilities outlines the roadmap for digital transformation. This strategy defines digitalization goals and the paths to achieve these goals.

- •

Digital Innovation: Another crucial element supporting the digital strategy is digital innovation. Firms strive to develop new products, services, and business models using digital technologies.

- •

Digital Tools: Technological tools required during the digital transformation process are also of great importance. These tools make business processes more efficient and facilitate the implementation of digital strategies.

- •

Digital Platform: Digital platforms supported by digital tools create firms’ digital ecosystems. These platforms enable data management, customer relationship management, and integration of operational processes.

- •

Digital Service: Digital services provided on digital platforms enhance the customer experience and optimize business processes. Firms can respond more quickly and effectively to customer demands through digital services.

- •

Digital Application: The final stage of digital transformation involves digital applications. These applications make a firm’s business processes, products, and services more accessible and usable in the digital environment.

- •

Digital Transformation: The integration of these elements constitutes digital transformation. Digital transformation is the process by which firms use digital technologies to transform their business models, processes, and customer relationships. This process enables firms to succeed in the digital world and gain a competitive advantage.

The integration of these nine elements enables sectors to better understand and apply the concept of digital transformation. This process, which begins with digital capabilities and ends with digital transformation, encompasses strategy, innovation, tools, platforms, services, and applications, forming the general framework for digital transformation in the sectors examined. In summary, digital transformation for sectors is a comprehensive process that involves using digital tools based on digital capabilities and strategies and conducting sales through digital platforms, services, and applications. In this process, firms assess and develop their digital capabilities and then create a digital strategy based on these capabilities. In accordance with this strategy, digital innovations and technological tools are used to establish digital platforms, which then offer various digital services and applications. Consequently, through the digital transformation process, firms strategically focus on digital tools, conduct sales through digital platforms, services, or applications, and adapt their business models to the digital world. Therefore, “sales” is one of the most significant outcomes of digital transformation for firms.

Another outcome is the creation of digital process innovations to optimize organizational and operational processes during the digital transformation process. In this context, firms can achieve reduced operational and/or organizational costs by leveraging digital process innovations, such as providing improved service quality (e.g., through digital communication channels) and new production capabilities (e.g., 3D printing). Accordingly, firms often turn to digital technologies for automating existing business processes (Wiesböck & Hess, 2020). Indeed, higher productivity associated with the introduction of new digital technologies often leads to lower employment levels (Pianta, 2009). Thus, the emergence of new digital technologies reduces the demand for lower- and middle-level employees performing routine manual and cognitive tasks (Bertani et al., 2020; Wiesböck & Hess, 2020; He et al., 2022; Du & Jiang, 2022). In this context, optimizing organizational and operational processes through digitalization, along with automating many processes, will significantly impact the number of personnel.

Thus, it is possible to examine the effects of digital transformation on firms through two primary outcomes: sales and personnel count. This approach is grounded in prior research, which highlights these variables as practical performance metrics and as reflective of firms’ ability to convert strategic initiatives into economic output. In particular, studies have shown that variations in these indicators can reliably capture changes in organizational efficiency and productivity following structural or technological shifts (Bartel, 1994; Becchetti et al., 2008; Ataullah et al., 2014; Sun & Yu, 2015). Considering these two themes, we conclude that the ratio outlined below could be used as an appropriate measure for evaluating the impact of digital transformation on firms:

ROD can clearly illustrate the impact of digital transformation on a firm’s efficiency and the contribution of digital strategies to sales. Specifically, this ratio correlates the net increase in sales achieved during the digital transformation process with the changes in personnel count during the same period. The net sales per employee ratio, on the one hand, demonstrates the extent to which a firm has realized the economic benefits of digital transformation and, on the other hand, reflects how the firm has achieved organizational efficiency gains during this process. This ratio is a critical indicator for quantitatively assessing the productivity improvements brought about by digital transformation and its effects on the workforce (Bartel, 1994; Ataullah et al., 2014; Sun & Yu, 2015).

In digital transformation processes, the adoption and implementation of digital technologies by firms typically lead to productivity increases and significant sales growth (Gao et al., 2025). However, these increases are not always directly associated with changes in personnel count (Zheng & Dai, 2025). Many studies show that, despite intensive investments in digital technologies, firms often struggle to convert these investments into proportional productivity gains, a phenomenon known as the “productivity paradox” (Zhang et al., 2024; Posti & Maiti, 2024; Chen & Zhang, 2024).

The ROD ratio can also be used for sectoral comparisons. For example, digital transformation is often adopted more rapidly in technology and service sectors, while it may progress more slowly in traditional manufacturing or energy sectors. These sectoral variations stem from differences in digital readiness, organizational flexibility, and resource allocation strategies (Becchetti et al., 2008; Sun & Yu, 2015). Such sectoral differences can be more clearly understood through comparisons of ROD ratios. These comparisons can reveal how firms in different sectors manage their digital transformation processes and optimize the economic outcomes of these processes.

Additionally, the ROD ratio can reflect the impact of digital transformation on a firm’s overall financial health. An increase in net sales typically indicates that the firm has successfully implemented its digital strategies; however, changes in personnel count during this process may result from organizational restructuring or improvements in operational efficiency (Pianta, 2009; Wiesböck & Hess, 2020; He et al., 2022). Therefore, the ROD ratio is important for analyzing not only the effects on sales but also the implications for the workforce.

Conceptualization and hypothesis developmentBased on the conceptualization of the digital transformation process outlined above, this study examines the digital maturity of firms and the outputs they achieve in three key dimensions: ROD; brand value; and digital activity. These variables were selected as tangible (e.g., operational efficiency) and intangible (e.g., corporate reputation) manifestations of digital transformation. Empirical models were developed to assess the impact of digital investment efficiency, represented by the ROD ratio, on the link between digital transformation indicators and firm performance.

Brand value and firm performanceBrand value, considered one of the intangible outputs of digital transformation in the research, encompasses elements such as consumer trust, perceived quality, and customer loyalty. According to the signal theory, strong brands reduce information asymmetry by sending signals to market actors about a firm’s reliability, product quality, and strategic reputation. This effect can directly impact a firm’s value by influencing investor perception and consumer behavior (Aaker, 2012; Keller, 2013). Existing studies support the view that the brand is a strategic value element for firms. Belo et al. (2014) stated that the brand power of firms reduces risk premiums by increasing the market value of firms. Similarly, Kumar et al. (2020) and Kumar et al. (2021) confirmed the direct impact of investments that increase a firm’s brand power on its financial performance, as measured by accounting- and market-based indicators. Wang and Sengupta (2016) revealed that brand equity serves as a strategic bridge between firms’ stakeholder relations and financial performance and that brand equity has a value-creating effect for firms, particularly in markets characterized by high competition. Furthermore, Madathil et al. (2025) stated that brand equity conveys trust and quality signals to the firm’s stakeholders, thereby playing a critical role in the formation of shareholder value.

In this context, the brand value variable was addressed as a result of the reputational gains that firms achieved during the digital transformation process. It was assumed that factors such as increased customer interactions and online visibility, especially with the digitalization initiatives of firms, positively affected the brand value and, accordingly, strengthened firms’ financial performances. Based on this, the research hypotheses developed within the scope of the study are presented below in sequence:

- •

H1: Brand value has a positive and statistically significant effect on Tobin’s Q.

- •

H4: Brand value has a positive and statistically significant effect on ROE.

- •

H7: Brand value has a positive and statistically significant effect on ROA.

The concept of digital activity used in the research refers to firms’ vision of digitalization and the orientations they create in line with the transformation strategies they develop in this direction. In this context, the digital activity variable reveals how firms manage the digital transformation process at the level of communication and institutional narrative.

The fact that firms carry out such discursive activities institutionally can be evaluated within the framework of strategic intent and signaling theory. The discourses in question can significantly impact investor perception, corporate trust, and market value. Li et al. (2023) analyzed the digital discourse level of firms through their annual activity reports, showing that the discourses in question are significantly related to the innovation outputs of firms. The research findings revealed that the frequency of digitally focused statements, in particular, serves as an important signal in terms of innovation and strategic dynamism at the firm level. Similarly, Chen and Zhang (2024) stated that firms express their digital transformation activities through corporate communication and technical investments, and this situation can also impact investor expectations and perceptions of market performance. Moreover, Zhao et al. (2024) and Zhai et al. (2022) emphasized that integrating digital transformation with organizational narratives creates a positive differentiation in the performance outcomes of firms.

Based on previous research results and logical inferences, it is assumed that digital activities will be associated with a firm’s performance. Based on this, the research hypotheses developed within the scope of the study are presented below in sequence.

- •

H3: Digital activity has a positive and statistically significant effect on Tobin’s Q.

- •

H6: Digital activity has a positive and statistically significant effect on ROE.

- •

H9: Digital activity has a positive and statistically significant effect on ROA.

The concept of digitalization can be defined as the integration of digital technologies into a firm’s business processes and strategic decision-making mechanisms. According to the resource-based perspective, digital capabilities are among the strategic resources that can provide sustainable competitive advantage for firms (Bharadwaj et al., 2013; Vial, 2021). However, the transformation of digital investments into financial outputs depends on the extent to which these technologies are used effectively and strategically (Brynjolfsson & Hitt, 1998; Ji et al., 2022).

Existing studies show that digital transformation generally has positive effects on a firm’s performance. For example, Zhai et al. (2022) and Guo and Xu (2021) emphasized that the digitalization activities of well-established firms in China have positive effects on operational efficiency and financial performance. Chen and Zhang (2024) stated that this effect becomes more pronounced, especially in the long term, while Zhao et al. (2024) stated that this effect varies depending on the firm size and technology intensity. On the other hand, Zhai et al. (2022) and Yavuz (2024) emphasized that the effect of digital investments on firm performance depends not only on the use of technology but also on the degree to which firms’ digital competencies are compatible with their corporate strategies. Ji et al. (2022) stated that the effect of digitalization on financial performance may emerge with a delay in time and therefore it is difficult to predict this effect in the short term.

In this context, the level of digitalization and the impact of firm performance on accounting-based (ROE, ROA) and market-based (Tobin’s Q) indicators were analyzed. In the study, the effect of digitalization on firm performance was measured through the ROD ratio, and the extent to which digitalization investments transformed this relationship was examined. Based on this, the research hypotheses developed within the scope of this study are presented as follows:

- •

H2: ROD has a positive and statistically significant effect on Tobin’s Q.

- •

H5: ROD has a positive and statistically significant effect on return on equity.

- •

H8: ROD has a positive and statistically significant effect on return on assets.

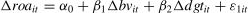

The research hypotheses are tested through the models provided in Eqs. (1-6).

The conceptual model of the research, developed based on the hypotheses, is presented in Fig. 3. According to the figure, in the first stage, the effect of digital activities and brand value on firm performance (ROA, ROE, Tobin’s Q) is examined. In the second step, ROD is added to the model, and the results are obtained. The impact of digitalization on firm performance was measured through the ROD ratio. Thus, the extent to which digitalization investments transformed this relationship was examined.

Variable descriptionsOur research data set was constructed from various sources. First, financial performance metrics for the firms under study, covering the period from 2009 to 2021 on an annual basis, were obtained from the Thomson Reuters Eikon database. Data on brand value were sourced from Statista and Brand Finance databases and published reports (Statista, 2024; Brand Finance, 2024). The keyword pool created to understand digital transformation in firms was developed from the annual reports of the firms from 2009 to 2021, with the frequency of keyword usage in the reports being measured.

Dependent variablesFinancial performance reflects how effectively a firm uses its resources to generate returns. Evaluating a firm’s financial performance is critical to understanding its capacity to generate value, allocate resources efficiently, and achieve sustainable growth. Consistent with previous literature, this study uses return on assets (ROA), return on equity (ROE), and Tobin’s Q to assess firm performance from accounting- and market-based perspectives. ROA captures operational efficiency by relating net income to total assets, while ROE indicates how effectively equity is used to generate profits. Tobin’s Q provides important insights into a firm’s market valuation relative to its asset base. These metrics have been widely used in numerous studies examining the financial performance of firms and are well-established in the literature. Moreover, they maintain their validity in current research analyzing firm performance in the context of strategic and technological transformations (Rosikah et al., 2018; Sudiyatno et al., 2020; Li & Wan, 2021; Stankevičienė & Valtoraitė, 2024; Al Azizah & Haron, 2025). In this context, ROA, ROE, and Tobin’s Q have been selected as the dependent variables for the study.

Independent variablesThe independent variables of the study aim to measure tangible and intangible aspects of digital transformation. First, ROD, a basic variable, was calculated by dividing a firm’s net sales by the number of employees and was used as a quantitative indicator reflecting the economic return on digital transformation investments. Second, brand value was considered as a strategic element representing a firm’s reputation and intangible assets. Third, digital activity, which reflects a firms’ discursive tendencies toward digitalization, was measured using the text mining method through the frequency of keywords starting with the root “digital” in their annual activity reports. Together, these three variables enable a multidimensional analysis of the investments firms make in digital transformation processes and the effects of these investments on financial performance.

MethodologyAccording to the conceptual framework of the study, it is posited that digitalization has a statistically significant effect on firm performance, and part of this effect is captured through the ROD indicator. The methodological approach of the study is structured into several sequential steps to ensure the validity and robustness of the empirical results.

Testing for cross-sectional dependenceBefore testing for unit roots or estimating regression coefficients, it is essential to examine cross-sectional dependence (CSD) in panel data. CSD refers to the correlation of variables across different cross-sectional units (e.g., firms). If unaccounted for, such dependencies can lead to biased estimates and incorrect inference. To identify the presence of CSD at the variable level, a series of tests were conducted, including the Breusch-Pagan LM, Pesaran scaled LM, bias-corrected scaled LM, and Pesaran CD tests. These tests confirmed statistically significant cross-sectional dependence across all variables used in the models. Therefore, appropriate second-generation methods and robust estimators were used in the subsequent stages of the analysis.

Unit root testingAfter confirming cross-sectional dependence, the Pesaran (2007) CIPS test was employed to assess the stationarity of the panel data. This test is appropriate for unbalanced panels and is robust to both T > N and N > T cases. If the null hypothesis of a unit root is rejected, the series is considered stationary. In this study, the test results provided evidence supporting the stationarity of the series.

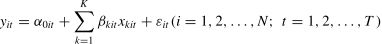

Model specification and estimationThe general panel regression model used in the study is presented in Eq. (1).

In Eq. (1), i represents the unit, t denotes the time period, yit is the dependent variable, xkit is the explanatory variable, βkit is the parameter associated with the explanatory variable, and εit is the error term. When working with a large number of units in panel data analysis, the likelihood of econometric assumption issues increases. In such cases, predictions made without considering issues such as changing variance, autocorrelation, or cross-sectional dependence can adversely affect the effectiveness of the results obtained (Un, 2015). Therefore, in this study, new estimates are made using estimators developed by Arellano (1987), Froot (1989), and Rogers (1993), which can produce robust standard errors when the error term is correlated within units but uncorrelated between units. These estimators minimize errors due to autocorrelation in panel data by producing robust standard errors (Yerdelen Tatoglu, 2012).

To address these concerns, robust standard error estimators developed by Arellano (1987), Froot (1989), and Rogers (1993) were employed. These estimators are particularly effective when error terms are autocorrelated within units but uncorrelated across units (Yerdelen Tatoglu, 2012), thus enhancing the accuracy of the model estimates. Model selection was performed using standard diagnostics: the F-test (for fixed effects vs. pooled OLS), the Breusch-Pagan LM test (for random effects vs. pooled OLS), and the Hausman test (for fixed vs. random effects). The results favored the use of random effects (RE) estimators across all models, as shown in Table 5.

Post-estimation diagnostic checksFollowing model estimation, diagnostic tests were conducted to evaluate core econometric assumptions: The Levene-Brown-Forsythe test was used to test for heteroskedasticity, and the results suggested unequal variances in several models. The Baltagi-Wu LBI test was used to test for autocorrelation, and some models showed signs of serial correlation. To detect residual-based cross-sectional dependence, the Friedman rank correlation test (Friedman, 1937) was applied. Although the Friedman test was originally designed for T > N panels, it was retained in this study as a nonparametric robustness check due to its rank-based structure. This characteristic makes it particularly suitable for data sets that exhibit outliers, high variance, and skewed distributions, which were clearly present in this study, e.g., ROE ranged from -24.89 to 281.62. The Friedman test results indicated no significant residual cross-sectional dependence, suggesting that the RE models effectively accounted for such dependencies.

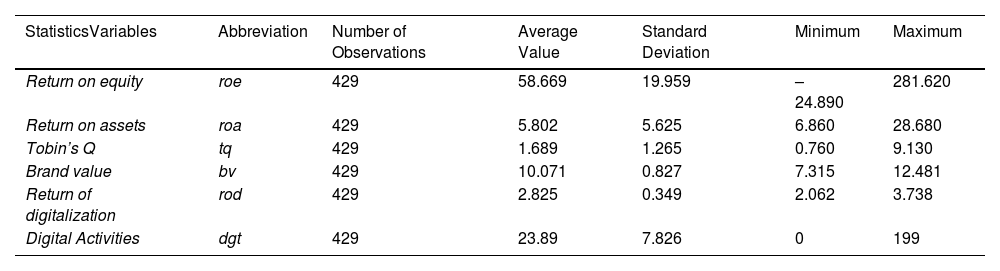

FindingsSummary statistics for the sample of 33 firms from the technology, retail, energy, finance, and automotive sectors covering the years 2009–2021 are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

Note: The term “digital activities-dgt” in Table 1 refers to the frequency of words related to digitalization that begin with the keyword “digital” in the firms’ annual reports, such as digital assistants, digital applications, digital content, digital advertising, digital agenda, digital platforms, and digital innovations.

ROE and ROA are used to measure financial performance, while ROD provides information about the returns on digitalization investments. The minimum and maximum values of ROD are quite broad, indicating significant differences among firms. When examining the frequency of the term “digital” (based on how many times this term appeared in the firms’ annual reports from 2009 to 2021), it is found to vary widely. Some firms’ reports did not use any words starting with the digital keyword, while others used them frequently. The high standard deviation indicates variability in the frequency of the term “digital.” This variability reflects the importance firms place on digitalization and their activities in this area. The variable allows for a quantitative assessment of firms’ levels of digitalization. The average level of digitalization is 2.825, showing a narrow range of variation. Therefore, it can be said that the returns on digitalization are largely similar among the firms studied. The average value for brand equity is 10.071 with a standard deviation of 0.827, indicating relatively less fluctuation in brand values. The low standard deviation suggests that brand values are concentrated around the mean and do not show large differences.

The line graph (Fig. 4) depicting ROD, a metric measuring the return of digitalization investments on firm performance, was examined to assess the average of firms over the 13 year period.

ROD (green dots) values represent the 13 year average for firms and show a wide distribution among firms. This indicates that digitalization investments have varying performance effects across different firms. The RODMean, represented by the red line, denotes the average ROD value for each firm. It is observed that the average ROD value follows the trend of individual ROD values. This smooths out individual fluctuations to reveal the overall trend. High RODMean values generally suggest a positive effect of digitalization investments on firms. The graph shows that RODMean values typically range between 2.5 and 3.5, indicating that digitalization generally provides a positive return. Table 2 presents the correlation matrix, which a priori expresses the relationship and direction among the variables.

According to Table 2, there is a statistically significant negative relationship between dgt and ROD. This indicates that as ROD increases, the frequency of using the term “digital” decreases. Additionally, a significant positive correlation is observed between dgt and bv, suggesting that firms with more frequent use of digital-related terms generally have higher brand value. Furthermore, brand value shows an overall positive correlation with other variables, especially with Tobin’s Q, ROA, and ROE, indicating a strong relationship. These relationships suggest that digitalization plays an important role in enhancing brand image, which, in turn, is reflected in firms’ brand values.

These findings underscore the positive correlation of digitalization and branding on firms’ financial performance. They demonstrate that firms can improve their brand value and financial performance by effectively utilizing digitalization strategies and brand management. In this context, considering digitalization and branding together is critical for firms’ long-term success. Panel regression analysis has been applied to further explore the relationships between variables, taking into account the correlation among units.

Since it is necessary to examine cross-sectional dependence before determining the stationarity of the series, the results related to cross-sectional dependence are presented in Table 3.

Cross-sectional dependence.

Note: Horizontal sections are independent of each other. CD∼N(0,1). Additionally, the values in parentheses indicate the p-value of the test statistic.

As a result of rejecting the null hypothesis for all variables, cross-sectional dependence, i.e., correlation among the cross-sections (firms) in the data set, has been detected. For series with cross-sectional dependence, the results obtained using the Pesaran (2007) CADF test, one of the second-generation unit root tests used to address this issue, are presented in Table 4.

Unit root test results.

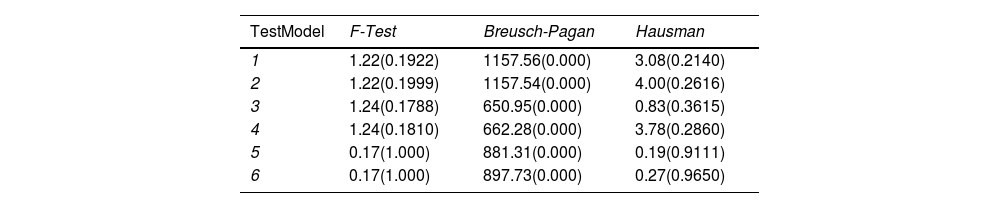

Based on the findings from the stationarity analysis, no stationarity was observed at the levels of all variables. Therefore, first, differences of the series were taken, and they were tested again at the same significance level, confirming that they became stationary. For the series that were made stationary, the F-test, Breusch-Pagan test, and Hausman test were applied to select the appropriate model for panel data models. The results obtained are presented in Table 5.

Model selection.

Note: The values in parentheses show the p-probability values of the relevant test statistic.

Model 1-2

Model 3-4

Model 5-6

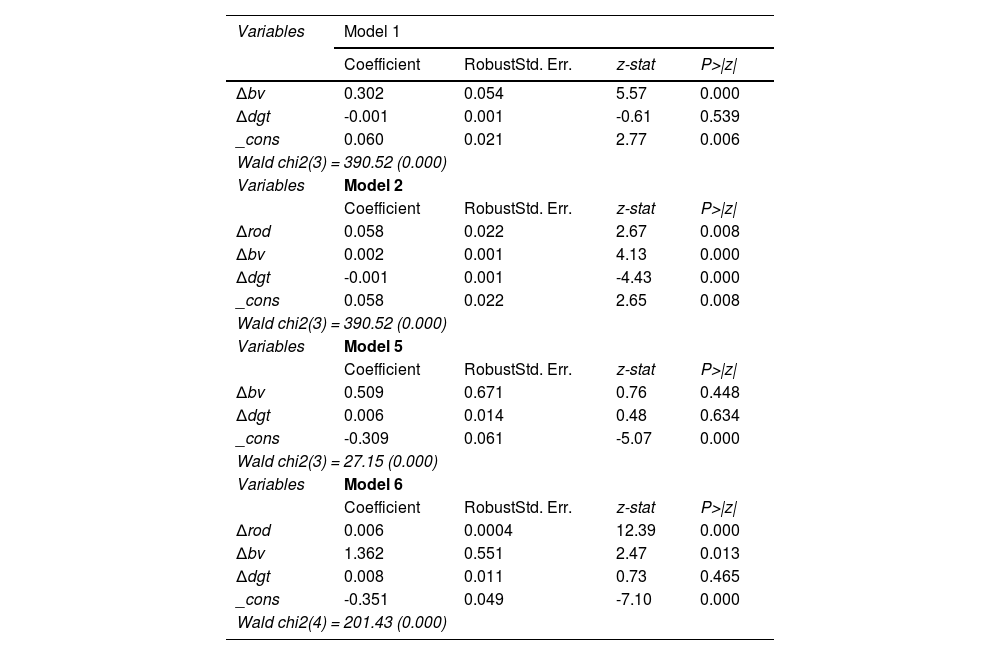

By comparing model specifications with and without the inclusion of the ROD variable, the empirical analysis enables an in-depth examination of whether the efficiency of digital investments significantly influences financial outcomes. This comparative structure not only tests the direct effects of digital activity (Δdgt) and brand value (Δbv) on performance indicators such as return on equity (Δroe) and return on assets (Δroa) but also isolates the contribution of ROD as a measure of how effectively digital strategies are converted into financial gains.

According to the results presented in Table 5, a restricted F-test was conducted to compare the classical model with the fixed effects model. The null hypothesis H0 that assumes unit and/or time effects are zero was not rejected. This indicates that there are no fixed effects and the classical model is appropriate. To decide between the classical model and the random effects model, the Breusch-Pagan test was applied. The null hypothesis H0that the variance of the unit effect is zero was rejected in all models. This suggests that the variance of the unit effects is significantly different from zero, indicating that the classical model is not suitable. According to the Hausman test results, the null hypothesis H0was not rejected in any of the models, leading to the conclusion that the random effects estimator is effective and valid. Given that the assumptions of the linear least squares models need to be examined, the relevant results are presented in Table 6.

Diagnostic tests.

Independence between cross-sections, which is one of the critical assumptions in panel data analysis, was evaluated with the Friedman rank correlation test (Friedman, 1937) applied to the residuals of the random effects models estimated in this study. This test is a nonparametric method based on Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient and provides reliable results especially in cases where the normal distribution assumption is not met or extreme values are present (Yerdelen Tatoglu, 2021). The firms included in the study belong to different sectors (technology, retail, energy, finance, and automotive), and, due to this diversity, financial data should be carefully evaluated in terms of sectoral heterogeneity and openness to extreme values. The rank-based structure of the Friedman test provides an advantage in such cases because the test statistic is calculated over the average of the rank correlations between the residuals of the cross-section units and is evaluated with the chi-square (χ²) distribution with T−1 degree of freedom.

Moreover, the p-values obtained in the applied Friedman test remained above the 5% significance level; therefore, the null hypothesis could not be rejected. This result shows that there is no significant cross-sectional dependence in the model residuals and therefore the Random Effects estimators used maintain their validity. This indicates that the units are independent of each other. To test the assumption of constant variance in random effects models, Levene, Brown, and Forsythe’s tests (Brown & Forsythe, 1974) were applied. The null hypothesis stating that the variances of the units are equal was rejected in all models except for Model 3 and Model 4. This suggests that the assumption of constant variance holds for Model 3 and Model 4, while the other models exhibit a problem of varying variance. For testing the assumption of autocorrelation in the research models, Baltagi et al.’s (1999) local best invariant tests were applied. Autocorrelation issues were detected in all models except Model 3 and Model 4, where the null hypothesis was rejected.

The diagnostic tests presented in Table 6 show different assumption violations among the models. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation were detected in models 1, 2, 5, and 6; therefore, these models were analyzed with the robust standard error estimators developed by Arellano, Froot, and Rogers. However, since these assumptions were met in models 3 and 4, the classical random effects model was accepted as valid, and the standard estimation method was used. Thus, each model was analyzed with the estimation method that best fits the data structure.

Based on the primary objective of the study, the goal was to understand the impact of digitalization on firm performance and to use the ROD variable to explain part of these effects. The results obtained from this method aim to emphasize the strategic importance of digitalization and contribute to optimizing firms’ digital transformation strategies. Therefore, predictions conducted to determine the role of the ROD variable in the model and how its inclusion enhances the model’s explanatory power are presented in Table 7. New predictions were performed using the adaptation of the random effects model to the estimator developed by Arellano (1987), Froot (1989), and Rogers (1993), which produces robust standard errors when the error term is correlated within units but uncorrelated between units. However, since no assumption violations were detected in the diagnostic tests applied to Model 3 and Model 4, standard estimation results were examined.

Arellano, froot, and rogers model estimation results.

The Wald test results for all estimated models indicate that they are statistically significant. The effect of ROD on Tobin’s Q and ROA dependent variables is found to be significant. This suggests that strategies related to digitalization have a substantial impact on performance. Brand value also generally has a significant effect. In Model 1, the effect of brand value is significant; in Model 2, it is also significant but with a small effect size. In Model 5, brand value is not significant, whereas in Model 6, it is significant and has a larger effect.

The effect of digital activity is generally found to be insignificant. This suggests that digital activity may not have a direct effect on the dependent variable, or that its impact on performance might occur through indirect channels. Furthermore, while the digital variable has a negative but statistically insignificant effect in Model 1, the inclusion of the ROD variable in Model 2 results in a change in the direction of the relationship to negative and statistically significant findings. Therefore, it is possible to argue that ROD plays an intervening role. It has been determined that the level of digitalization, in conjunction with ROD, has a positive effect on Tobin’s Q. In other words, as digitalization and ROD increase, a positive effect on Tobin’s Q is observed. While digitalization alone does not have a significant impact, its interaction with ROD generates a meaningful effect. The shift from a negative to a positive effect of digitalization on Tobin’s Q with the inclusion of ROD indicates that the interaction between digitalization and ROD creates a positive impact and plays a significant role in firm valuation. Thus, it can be concluded that firms should align their digitalization strategies with the objective of enhancing ROD. Maximizing the return on investments made during the digitalization process emerges as a crucial factor in improving firm performance.

In summary, these models indicate that ROD acts as an important factor in the relationship between digitalization and firm performance, with brand value playing a significant role in this process. However, the effect of digital activity alone has not been found to be significant. ROD and brand value, especially in models 2 and 6, highlight the potential to enhance firm performance significantly. Firms should aim to increase net sales per employee while implementing digitalization strategies. This will maximize the impact of digitalization on profitability. Specifically, increasing net sales per employee is crucial for maximizing the profitability effects of digitalization investments. This strategy can help firms achieve a sustainable competitive advantage and improve their financial performance. The results of the random effects regression predictions for Model 3 and Model 4 are presented in Table 8.

Random effects model estimation results.

Model 4 has a higher explanatory coefficient (R² = 0.2217) compared to Model 3 (R² = 0.1450). This indicates that the inclusion of the ROD variable has improved the model’s explanatory power. Therefore, it can be said that Model 4 has a better explanatory capacity than Model 3. The analysis results show that changes in brand value have a specific impact on ROE. In other words, an increase in a firm’s brand value generally has a positive effect on ROE. For firms, this suggests that marketing and brand management strategies are effective and that there is a strong connection between customer loyalty and financial success. However, the effect of digital activity has been found to be statistically insignificant in both models. Brand value and ROD have significant and positive effects on ROE (Model 4). The effect of digital activity on ROE is not significant, indicating that this variable does not have a pronounced direct effect on financial performance.

According to the findings of the study, the research hypotheses are evaluated as follows: In Model 1 and Model 2, the effect of brand value on Tobin’s Q is found to be significant, and therefore the hypothesis regarding brand value is supported. The effect of digitalization on Tobin’s Q (Model 1) is not statistically significant; therefore, the hypothesis regarding digitalization is rejected. However, when the ROD variable is added (Model 2), its effect on Tobin’s Q becomes positive and significant. This shows that ROD has a significant effect on firm value and supports the ROD hypothesis. Similarly, in Model 3 and Model 4, brand value has a significant and positive effect on ROE; this shows that the brand value hypothesis is supported. The effect of digitalization on ROE is not significant; therefore, this hypothesis is rejected. However, in Model 4, the effect of ROD on ROE is found to be significant and positive; therefore, the ROD hypothesis is supported here as well. Brand value is not found to be significant in Model 5 but is found to be significant and positive in Model 6; therefore, the hypothesis regarding brand value is partially supported. On the other hand, the effect of digitalization on ROA is not significant and therefore rejected. On the other hand, the effect of the ROD variable on ROA is found to be positive and significant in Model 6, which supports the hypothesis regarding the effect of ROD on ROA.

DiscussionThe research aims to comprehensively analyze the financial effects of digital transformation. Specifically, the goal is to deeply examine the impact of digital transformation on firms’ financial performance and investigate how this impact can be measured. The findings reveal that digitalization creates differences among firms and that there is a negative relationship between ROD and the frequency of words indicating digital activities in firms’ reports. Additionally, the frequent use of these words is positively related to a firm’s brand value, supporting the potential of digitalization to enhance brand value. The results indicate that digitalization plays a critical role in helping firms gain a competitive advantage. In particular, the positive impact of digitalization on brand value shows that digitalization not only provides operational efficiency but also increases a firm’s perceived value. The results demonstrate that firms need to manage their digitalization strategies effectively, as these strategies have significant effects not only on internal processes but also on external perception and brand value. Indeed, these findings are supported by existing studies (Matt et al., 2015; Siebel, 2019; Bican & Brem, 2020; Kim & Kim, 2022).

Our other findings reveal that digitalization generally has a positive effect on firms’ financial performance. Indeed, this result aligns with some studies in the existing literature (Huang et al., 2020; Yasmin et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Chen & Srinivasan, 2024). However, unlike other studies, our findings suggest that, while the ROD variable, proposed as a ratio to measure the return on digitalization investments, positively impacts firms’ financial performance, this effect varies from firm to firm. Specifically, it has been observed that firms with a high ROD ratio use digitalization-related terms less frequently in their annual reports. This could indicate that digitalization has become a routine part of these firms’ daily operations and thus is less emphasized in reports. Additionally, it was found that firms with a high ROD ratio also experience positive effects on their financial performance.

The positive relationship between ROD and brand value is consistent with the literature suggesting that digitalization investments strengthen brand image and potentially have a positive impact on firms’ long-term financial performance (Wang & Sengupta, 2016). The strong effect of digitalization on brand value and financial performance underscores that firms’ digital strategies can create significant impacts not only on internal operational improvements but also on brand management and consumer perception. This finding contrasts with the views of Ho and Mallick (2010) and Chae et al. (2014), indicating that digitalization should not only be seen as a cost factor but also as a long-term investment.

Moreover, the negative relationship between the frequency of using digital keywords and ROD provides evidence that firms need to use digitalization investments more effectively, treating digital transformation not merely as a slogan but as a genuine value-creation tool. This situation suggests that firms should review their digital strategies and adopt more sophisticated approaches to enhance the effectiveness of these strategies.

The ROD ratio emerges as a critical indicator for measuring the effects of digital transformation on firms. This ratio directly reflects the efficiency gains provided by digitalization, offering a valuable tool for assessing the success of firms’ digital strategies. Our study demonstrates that firms with a high ROD ratio achieve digital transformation more effectively and that this transformation positively impacts their financial performance.

Additionally, these findings reveal that digital transformation enhances not only operational efficiency but also a firm’s overall competitive strength. Firms with a high ROD ratio obtain a stronger market position and achieve sustainable growth. This underscores that digital transformation investments provide not just short-term cost savings but also long-term strategic advantages.

In conclusion, considering the ROD ratio when evaluating the effects of digital transformation processes on financial performance is crucial for firms to optimize their digital strategies and gain a competitive advantage. In this context, future research is recommended to explore the ROD ratio in more detail and examine the effects of digital transformation on sectoral and regional differences.

ConclusionThis study aims to comprehensively address the effects of digital transformation on firms’ financial performance and the role of the ROD ratio in measuring these effects. The findings of the research demonstrate that digital transformation yields positive financial outcomes, particularly in terms of sales and personnel productivity, and that the ROD ratio emerges as a critical tool in evaluating these effects.

Digital transformation and financial performanceThe research results provide strong evidence that digital transformation processes enhance firms’ financial performance. Firms have improved their operational efficiency and customer experiences by investing in digital technologies. This has led to tangible financial benefits in the form of cost savings and revenue increases. Specifically, the impact of digital transformation projects on sales volume and net profit provides compelling evidence that digital strategies have become an integral part of business strategies.

Role of the ROD ratioThe ROD ratio has been evaluated as a crucial tool for measuring the financial effects of digital transformation. The use of the ROD ratio has enabled the quantitative measurement of the financial impacts of digital transformation and facilitated a detailed analysis of these effects. This ratio serves as an important indicator for more meaningful evaluation of the financial outputs of digital transformation and helps firms monitor the effectiveness of their digital strategies.

ImplicationsThe research findings reveal that companies should prioritize brand management and human resources efficiency elements in their strategic management practices. The positive impact of brand value on firm performance shows that investments made in the brand directly affect not only customer perception but also financial performance. In this context, firm management should strengthen its emphasis on digitalization and digital transformation, thereby sending positive signals to stakeholders.

Additionally, the impact of ROD on firm performance is significant. Since productivity per employee contributes to the firm’s positive performance, the digital competencies of employees are becoming increasingly important. Therefore, firm management should enhance the digital competencies of employees, prioritize digital transformation at a higher level, and thereby facilitate employees’ adaptation to digital innovations. Training, information meetings, and technical support will be helpful for adaptation.

From the perspective of dynamic capabilities, the perception of sectoral dynamics, a firm’s ability to seize opportunities, and the restructuring of the resource base will be related to the effectiveness of the digital transformation and digitalization process. Thus, companies will have the chance to anticipate and take action on new trends in the sector. This may be vital for a firm to achieve and maintain its competitive advantage. Therefore, it would be beneficial to establish monitoring mechanisms at all levels of a firm.

From an institutional theory perspective, efforts to adapt to sectoral trends will prevent a firm from becoming rigid and ensure its flexibility. In this context, it is essential to closely monitor the activities of policymaking and regulatory institutions and develop a clear understanding of the incentives and institutional pressures they apply in the context of digitalization. This ensures that digital transformation occurs not just symbolically but in a concrete and operational sense. This adaptation both legitimizes a firm and enables it to compete. Companies need to have experts to follow institutional developments.

Limitations and future researchWhile the findings of our study provide valuable insights, certain limitations should be considered. The ROD ratio used in the study is an important tool for measuring the impact of digital transformation on efficiency. However, this ratio may not fully reflect all aspects of digital transformation or a firm’s digital maturity. One important limitation of this study pertains to the operationalization of the ROD metric. Due to the unavailability of consistent and comprehensive firm-level disclosures on digital-specific revenues, investments, or operational costs, this study employs the net sales-per-employee ratio as a proxy for digital productivity. While this measure is widely used in the empirical literature as an indicator of overall firm efficiency, it does not directly isolate financial outcomes attributable solely to digital transformation initiatives. Therefore, ROD should be interpreted as a broad proxy for firm-level output efficiency in a digitalizing environment rather than a precise measurement of digital returns. Future research could enhance the specificity of this metric by integrating proprietary data sets or firm-disclosed financial statements that detail digital revenue streams, digital investment intensity, or cost savings related to automation and technological adoption.

The research focuses on firms within a specific sector or geographical region. Given that digital transformation processes can vary significantly across sectors and regions, caution should be exercised when generalizing these findings to other sectors or regions. Therefore, conducting similar research in different sectors and regions could enhance the generalizability of the findings.

In digital transformation processes, the human factor plays a significant role alongside technology. The study does not address aspects such as employees’ adaptation to these processes, training needs, or resistance to change. This omission may result in overlooking a crucial dimension that could impact the success of digital transformation.

Future research should aim to validate the findings of this study in a broader context by examining various sectors and regions. Utilizing long-term and comprehensive data sets to conduct in-depth analyses of the financial impacts of digital transformation is essential. Additionally, understanding the effects of digital transformation on firm performance would benefit from considering human factors, levels of digital maturity, and sectoral dynamics. Such research could provide more comprehensive insights into enhancing the effectiveness of digital transformation strategies and improving financial performance. Ultimately, understanding the positive effects of digital transformation on financial performance is a critical step for strategic decision-making in firms. The ROD ratio emerges as an effective tool for measuring these effects, and evaluating this area from a broader perspective can provide valuable contributions to academic literature and practical applications.

Funding statementThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of generative AI useDuring the preparation of this work, generative AI tools were used to enhance language clarity and strengthen the writing quality. The authors reviewed and edited the content thoroughly and take full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMelih Sefa Yavuz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Visualization. Hasan Sadık Tatlı: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Conceptualization, Visualization. Gözde Bozkurt: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology.

The authors declare no competing interests.