Multinational companies are increasingly under pressure to integrate decarbonisation into their business models as a sign of climate leadership and as a strategy for their long-term value. Institutional investors play a key role in this, both directly, by influencing the adoption of decarbonisation strategies, and indirectly, by promoting climate governance mechanisms within companies that facilitate the implementation of decarbonisation initiatives and strategies. Analysing a sample of 4,956 companies from 2015 to 2022, we find that institutional investors positively influence companies' decarbonisation strategies through both direct and indirect channels. Although this is not affected by institutional investors' investment horizon or objectives, some types of institutional investors, in particular cross-holdings, financial institutions and pension funds, strengthen governance frameworks and promote more ambitious climate strategies. These findings underscore the critical role of institutional investors in driving corporate climate action, and highlight the need for policymakers and corporate leaders to consider investor-driven governance structures as a lever for accelerating decarbonisation.

The urgency of tackling climate change has placed multinational companies (MNCs) at the centre of global attention, as they are one of the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions (Atta-Darkua et al., 2023; França et al., 2023; Orazalin et al., 2024). As key players in the global economy, MNCs have not only the ability but also the responsibility to adopt strategies that help mitigate the effects of climate change by returning to pre-industrial levels of emissions, in order to avoid the significant economic and social consequences of continuing with the current development model (Christophers, 2019; Benz et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2023). As a result, they are under increasing pressure to change their business models and operations to reduce their carbon footprint and increase their resilience to climate risks (Aggarwal & Dow, 2012; Fan et al., 2021; França et al., 2023). In addition to physical risks related to the occurrence of extreme climate events that may disrupt their operations (Kim et al., 2023), they face transition risks associated with the shift to a decarbonised economy (Song & Xian, 2024), including regulatory risks arising from the proliferation of climate-related regulations that force them to rethink their business model and operations (Bose et al., 2024), reputational risks, and changes in demand due to increased consumer sensitivity to these issues (Luo et al., 2023). As a result, climate risk management and emissions reduction have become key elements of corporate sustainability and long-term survival (França et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024).

In this context, investors, regulators and other stakeholders are increasingly demanding that companies define clear commitments to reducing emissions and adopt strategies for removing carbon from their business models (Ameli et al., 2020; Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2020; Safiullah et al., 2022; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023). Decarbonisation means working in an ambitious and credible way to reduce emissions (Angelin, 2024). It encompasses all business initiatives that contribute to achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, including both the adoption of climate change mitigation technologies (Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2023) and the transition to a low-carbon business model centred on the use of renewable resources, optimising their use, etc. (Johnson et al., 2023; Kolasa & Sautner, 2024; López-Cabarcos et al., 2024) and the redesign of organisational processes and routines along the value chain, breaking with established practices (França et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2024).

The growing recognition of climate change as a systemic risk has put institutional investors at the forefront of driving corporate climate action (Christophers, 2019; Ameli et al., 2020; Stroebel & Wurgler, 2021; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023). The material impact of climate risks - from physical disruption to regulatory uncertainty - threatens the stability and profitability of investment portfolios (Atta-Darkua et al., 2023). As a result, institutional investors are motivated to ensure that companies adopt robust climate risk management strategies to mitigate potential losses and capitalise on the opportunities presented by the low-carbon transition (Krueger et al., 2020; Safiullah et al., 2022; Angelini, 2024; Drobetz et al., 2024). In addition, these investors are acutely aware of the reputational risks associated with funding companies that are perceived as laggards in climate action (Benz et al., 2020; Benlemlih et al., 2023).

As key stakeholders in global financial markets, institutional investors exert significant influence on corporate decision-making processes and strategies (Ozer et al., 2010; Melis & Nijhof, 2018; Klettner, 2021; Drobetz et al., 2024; McDonnell & Gupta, 2024). Their ability to mobilise large pools of capital enables them to act as stewards of good governance and sustainability (Ameli et al., 2020; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Velte, 2023; Fan et al., 2024). Whether through "exit strategies" (disinvestment) or by using their "voice" through the exercise of voting rights and/or active engagement in corporate governance through the appointment of independent directors, institutional investors have increasingly pushed for the integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues into corporate strategies (García-Sánchez et al., 2020a, 2023b; Benlemlih et al., 2023; Drobetz et al., 2024). By encouraging companies to reduce their carbon footprints and align with international climate goals, institutional investors seek to ensure the resilience and sustainability of their investments while supporting a broader societal shift towards decarbonisation (McDonnell & Gupta, 2024). Investor-led initiatives, such as the Climate Action 100+ coalition, exemplify collective efforts to hold companies accountable for their climate commitments and encourage the adoption of sustainable business models (Atta-Darkua et al., 2023; Kolasa & Sautner, 2024).

As active watchdogs, institutional investors have a considerable influence on the adoption of climate governance mechanisms (Benjamin & Andreadakis, 2019; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2024; García-Sánchez et al., 2024). In the context of climate change, corporate governance mechanisms play a crucial role in the operationalisation of decarbonisation strategies (García-Sánchez et al., 2023a). Effective corporate governance structures are fundamental to managing the risks and capitalising on the opportunities associated with the low-carbon transition. Empirical evidence suggests that companies with robust climate governance frameworks are more likely to achieve significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions (Aggarwal & Dow, 2012; Velte, 2023). Hence, the concept of climate governance has become increasingly popular, as a long-term approach to corporate governance is needed to address the challenges of climate change (Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; García-Sánchez et al., 2024). By embedding sustainability into corporate decision-making, climate governance mechanisms create a structured approach to managing climate risks and opportunities (Bui et al., 2020; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2024). These mechanisms not only facilitate the internal alignment of corporate strategies with climate goals, but also increase the trust by external stakeholders in the company and attract capital from investors seeking to support sustainable practices (Benjamin & Andreadakis, 2019).

Despite the growing research in the role of institutional investors in promoting corporate climate action (Velte, 2023), there is a notable gap in the existing literature. Although much of this research has focused on the direct influence of institutional investors on corporate sustainability (e.g., García-Sánchez et al., 2020a; Aguilera et al., 2021; Bueno-García et al., 2022), highlighting the importance of ESG engagement and shareholder activism, limited attention has been paid to the organisational processes and governance structures that mediate this relationship by translating investor demands into implementable corporate strategies (Benlemlih et al., 2023; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2024).

This study seeks to fill this gap by providing a nuanced understanding of the interplay between the influence of institutional investors, governance mechanisms and corporate climate strategies. Specifically, we examine the influence of institutional investors on corporate decarbonisation strategy and whether their direct influence is complemented by the mediating effect of the development of climate governance within the companies in which they invest. Based on a sample of 4956 companies for the period 2015–2022 (21,914 observations), we find positive direct and indirect effects of institutional investors on the development of a decarbonisation strategy by the companies they have invested in Both effects are unaffected by the investment horizon (long-term or short-term) and objectives (strategic or financial) of the institutional investors. The results also show that some types of institutional investors, specifically cross-holdings, financial institutions and pension funds, strengthen the climate-related governance mechanisms of MNCs and drive more ambitious decarbonisation strategies.

This study makes several important contributions to the literature. First, it explores the role of institutional investors in promoting substantive corporate climate action by showing that they are central to driving corporate decarbonisation strategies through both direct and indirect mechanisms. Second, we advance the theoretical understanding of the mediating role of climate governance by providing empirical evidence on how climate governance mechanisms facilitate the alignment of corporate actions with investor expectations. Third, we show that differences in institutional investors' investment horizons and objectives do not affect their direct and indirect influence on corporate decarbonisation strategies, providing novel evidence on the effect of heterogeneity within the institutional investor landscape on climate-related practices. Finally, by focusing on the specific context of multinational corporations, the research addresses the unique challenges and opportunities associated with aligning investor influence and corporate climate action in complex, globalised environments.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: the next section briefly presents the theoretical framework and the development of hypotheses on the direct and indirect effects of institutional investors on corporate decarbonisation strategies. The research design (sample selection, empirical models and variables) is described in the third section. The results are presented and discussed in the fourth section, while the final section summarises the main conclusions of this study, with a discussion of its theoretical and practical implications, as well as its limitations and some avenues for future research.

Theoretical framework and research hypothesesThe role of institutional investors in corporate decarbonisationThe link between corporate sustainability and institutional ownership has been analysed within different theoretical frameworks, among which agency theory stands out (Ozer et al., 2010; Bebchuk et al., 2017; Velte, 2023). It provides a robust framework for understanding the dynamics between principals (shareholders) and agents (managers) in corporate governance (Melis & Nijhof, 2018). It posits that principal-agent relationships inherently involve competing interests and information asymmetries (Jensen & Meckling, 1976). As agents, managers may prioritise personal or short-term goals over the long-term interests of the shareholders, leading to potential misalignments in firm strategies (Shleifer & Vishny, 1986). To mitigate these conflicts, shareholders use mechanisms such as performance-based incentives, monitoring systems and governance interventions.

When applied to climate change, agency theory highlights the critical role of institutional investors in aligning managerial actions with broader environmental and societal goals (Klettner, 2021). Institutional investors, as principals with significant stakes, are in a unique position to influence managerial behaviour towards the creation of sustainable value (Kolasa & Sautner, 2024). They use their substantial financial resources and reputational influence to overcome managerial inertia and ensure that decarbonisation strategies are not only formulated but also effectively implemented (Ozer et al., 2010). Their ability to monitor corporate performance and advocate transparency reduces information asymmetries and ensures that managerial decisions take ESG factors into account, including the adoption of decarbonisation strategies (Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Angelini, 2024). This highlights the role of institutional investors as both monitors and enablers of corporate climate action, bridging the gap between shareholder interests and management priorities (Klettner, 2021; Benlemlih et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2024).

The growing integration of ESG criteria into investment decision-making underscores their commitment to mitigating climate risks that could threaten portfolio value (Krueger et al., 2020; Angelini, 2024). Moreover, institutional investors have an incentive to advocate decarbonisation, as part of their fiduciary duty to protect beneficiaries from the systemic risks of climate change (Melis & Nijhof, 2018; Ameli et al., 2020; Safiullah et al., 2022; Drobetz et al., 2024). This advocacy manifests itself through mechanisms such as proxy voting, direct engagement, and participation in collaborative initiatives such as the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) or Climate Action 100+ (Klettner, 2021; Atta-Darkua et al., 2023; Benlemlih et al., 2023; Fan et al., 2024). These actions compel corporate managers to adopt science-based emissions targets and invest in green technologies, thereby promoting alignment with global climate goals (Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023).

In sum, by mitigating agency conflicts and championing long-term environmental goals, institutional investors drive the adoption of decarbonisation strategies and align corporate practices with the imperatives of a low-carbon economy (Krueger et al. 2020; Kolasa & Sautner, 2024). Empirical evidence supports the existence of such a stewardship role, with studies finding a positive correlation between the presence of institutional investment in a firm and the adoption of sustainable practices (Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2023; Benlemlih et al., 2023; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Velte, 2023). The following hypothesis is therefore formulated:

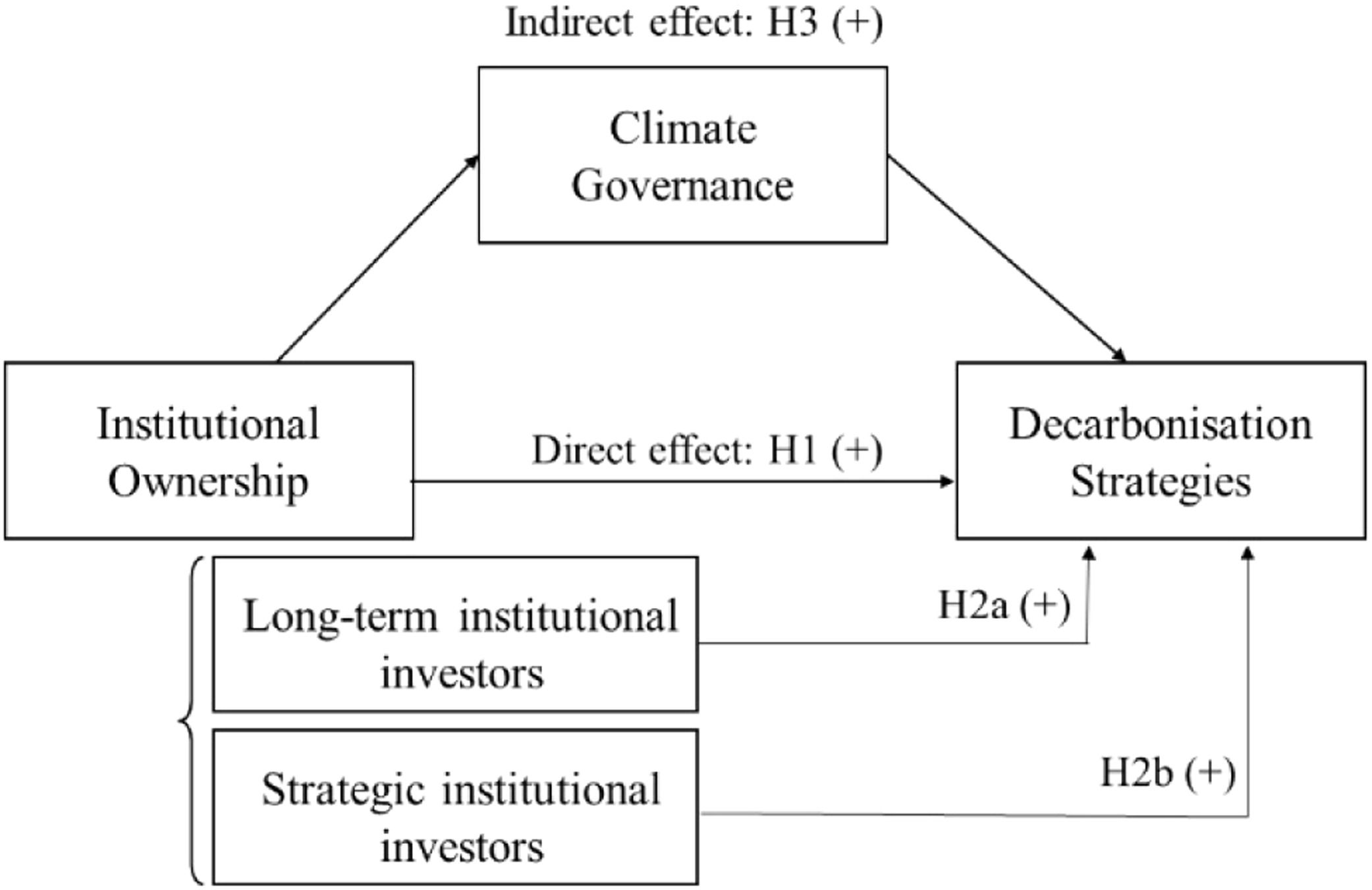

H1: There is a positive association between institutional ownership in a firm and the adoption of decarbonisation strategies.

Previous research has shown that the extent and nature of institutional investors' influence on corporate sustainability strategies, including decarbonisation initiatives, is significantly shaped by their investment horizons (García-Sánchez et al., 2020a, 2022; Safiullah et al., 2022; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2023; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Velte, 2023; Drobetz et al., 2024). Institutional investors with long-term investment horizons, such as pension funds, recognise the financial and reputational risks associated with failing to address climate change and are more likely to advocate robust sustainability measures to mitigate these risks, as they seek to secure the lasting value of their portfolios (Krueger et al., 2020; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Drobetz et al., 2024; Moldovan et al., 2024). Conversely, institutional investors with short-term investment horizons, such as hedge funds, may be less committed to climate action, focusing instead on immediate financial returns and performance (Caby et al., 2022; Christophers, 2019; Ameli et al., 2020; Safiullah et al., 2022; Drobetz et al., 2024). In addition, long-term investors are more likely to engage in sustained engagement with corporate boards and participate in collaborative initiatives such as the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance (McDonnell & Gupta, 2024; Nikolaeva et al., 2024). In contrast, short-term institutional investors may be less motivated to pressure companies to adopt decarbonisation strategies, given the deferred nature of the financial benefits associated with sustainability (García-Sánchez et al., 2020a; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2023; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2022).

On the other hand, according to Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023), the classification of institutional investors according to their investment horizon should be complemented by taking into account the underlying objectives (financial or strategic) of their investment portfolio management (Ozer et al., 2010; Bueno-García et al., 2022), since, as shown by García-Sánchez et al. (2020a), the influence of institutional investors on the environmental strategies of their portfolio companies may differ depending on their objectives.

In light of the above, the following hypotheses are formulated:

H2a: The positive influence of institutional investors on the adoption of corporate decarbonisation strategies depends on their investment horizon, so that only long-term investors will have a positive influence on the adoption of corporate decarbonisation strategies.

H2b: The positive influence of institutional investors on the adoption of corporate decarbonisation strategies depends on their underlying portfolio management objectives, so that only those with strategic investment objectives will have a positive influence on the adoption of corporate decarbonisation strategies.

As stewards of capital with significant stakes in companies' equity, institutional investors use their influence to advocate governance structures that prioritise sustainability (Klettner, 2021; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023). The motivation for institutional investors to engage in climate governance stems from their recognition of the significance of climate risks (Ameli et al., 2020; Krueger et al., 2020; Atta-Darkua et al., 2023; Kolasa & Sautner, 2024; Moldovan et al., 2024), which leads them to demand climate change information (Ilhan et al., 2023; Pham et al., 2024) and penalise companies that fail to disclose it (Matsumura et al., 2024). Their expectations of transparency and accountability are driving the adoption of practices such as ESG-linked compensation and the disclosure and assurance of climate-related information (Haque & Ntim, 2020; García-Sánchez et al., 2022; Velte, 2023). They are also driving the establishment of sustainability committees and the integration of climate-related risks into governance frameworks (Melis & Nijhof, 2018; Basse Mama & Mandaroux, 2022; Aibar-Guzmán et al., 2024). By ensuring that companies adopt robust governance mechanisms aligned with broader environmental goals, such investors not only mitigate the potential for financial losses associated with regulatory changes, reputational damage and the physical consequences of climate change (Angelini, 2024; McDonnell & Gupta, 2024), but also provide a structural and strategic basis for implementing decarbonisation initiatives that reinforce a commitment to the creation of sustainable value (Bui et al., 2020; Goud, 2022; Kavadis & Thomsen, 2023; Orazalin et al., 2024).

From an agency theory perspective, climate governance mechanisms address two key dimensions of the principal-agent problem: information asymmetry and goal alignment. By requiring publicly available, independently assured climate disclosures, climate governance reduces information asymmetry (García-Sánchez et al., 2023a) and enables institutional investors to effectively monitor companies’ progress towards decarbonisation. At the same time, linking executive pay to ESG performance aligns managers’ incentives with the long-term sustainability goals of institutional investors and encourages a commitment to achieving emissions reduction targets (Ludwig & Sassen, 2022). In this way, climate governance mechanisms provide a structured approach to embedding climate change concerns into corporate strategy, ensuring that investor pressure is translated into tangible action (Luo & Tang, 2021; Goud, 2022; Principale & Pizzi, 2023; García-Sánchez et al., 2024). This mediating role is particularly significant in the context of MNCs, where the complexity of operations and stakeholder expectations can dilute the direct influence of institutional investors. Therefore, the following hypothesis is formulated:

H3: Climate governance acts as a mediating mechanism in the relationship between institutional ownership and corporate decarbonisation strategies: institutional investors positively influence climate governance, which in turn facilitates the adoption of decarbonisation initiatives.

Fig. 1 summarises the research model.

MethodSampleTo test the research hypotheses, we selected the main MNCs for which sustainability or ESG information is available in the Refinitiv database. Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023) and García-Sánchez et al. (2023b), among others, confirm that the visibility, size and activity of these companies are strongly associated with a high environmental impact and the availability of the necessary resources and capabilities to carry out a transition to a low-carbon business model, affecting all the links in their value chains. The use of the Refinitiv database has important advantages from an academic point of view, in particular its (i) broad coverage of policies, projects and initiatives in the three ESG dimensions and (ii) continuous availability over time, which favours the dynamic study of corporate commitments and actions in the field of sustainability. It contains information on >15,000 companies located in 76 different geographical areas.

To obtain the sample used to estimate the empirical model, we followed a three-step procedure. In the first step, we identified all MNCs with available information on their public commitment to decarbonisation in the period 2015–2022. To do this, we consider the companies for which the presence (value 1) or absence (value 0) of this commitment is identified. In the second step, we downloaded the necessary information to build the dependent, independent and control variables. We then dropped the MNCs that did not have the data for some of these variables. Finally, we checked whether the information for each MNC was available for at least 5 consecutive years, in order to control for unobservable heterogeneity. We eliminated firms with gaps or with only a few years in the panel. The application of these criteria resulted in an unbalanced panel of 4956 firms and a total of 21,914 observations.

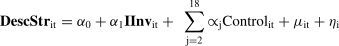

ModelsIn order to test the hypotheses, we will use a four-stage model following Simith et al. (2019), which includes the construction and estimation of three equations and the testing of the mediation effect using the KHB approach of Karlson and Holm (2011). The first equation is designed to analyse the effect that institutional investors (independent variable IInv) have on the climate governance (mediating variable CGov) of the companies in which they have invested. The second equation analyses the direct impact of institutional investors (independent variable IInv) on companies' decarbonisation strategy (dependent variable DescStr). In the third equation, the dependency model determines the effect of institutional investors (independent variable IInv) and climate governance (mediating variable CGov) on corporate decarbonisation strategy (dependent variable DescStr). All equations include a vector of the necessary control variables to avoid biased results.

where i ranges from firms 1 to 4956 and t from 2015 to 2022. β,α and δ are the coefficients from the variables -constant, independent, mediator and control- included in the proposed equations. µ and η refer the decomposition of random error.Regarding our hypotheses H1, H2a and H2b, the existence of a direct effect of institutional investors' influence on companies' decarbonisation strategy requires that ∝1>0 and be statistically significant. Regarding hypothesis H3, the existence of an indirect or mediating effect requires that (i) in the first equation, β1>0, which would imply that institutional investors determine the strength of climate governance, and (ii) in the third equation, the effect of the strength of climate governance, determined by δ2>0, must be econometrically significant, and the effect of institutional investors must be smaller than that observed in Eq. (2), that is, α1>δ1>0. In the case that δ1 is not significant, the impact of CGov corresponds to a total mediation effect, while if it is significant, there is a partial mediation effect. In the latter case, the presence of institutional investors has both a direct and an indirect effect on the decarbonization strategy. These effects will be determined by the KHB approach.

Eq. (1), given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable CGov, is estimated using ordinal regressions for panel data. Eqs. (2) and 3, given the censored nature of DescStr, are estimated using Tobit regressions for panel data. Both approaches control for unobservable heterogeneity through firm-specific effects (η). Causality is corrected by using a time lag as an instrument for the explanatory variables.

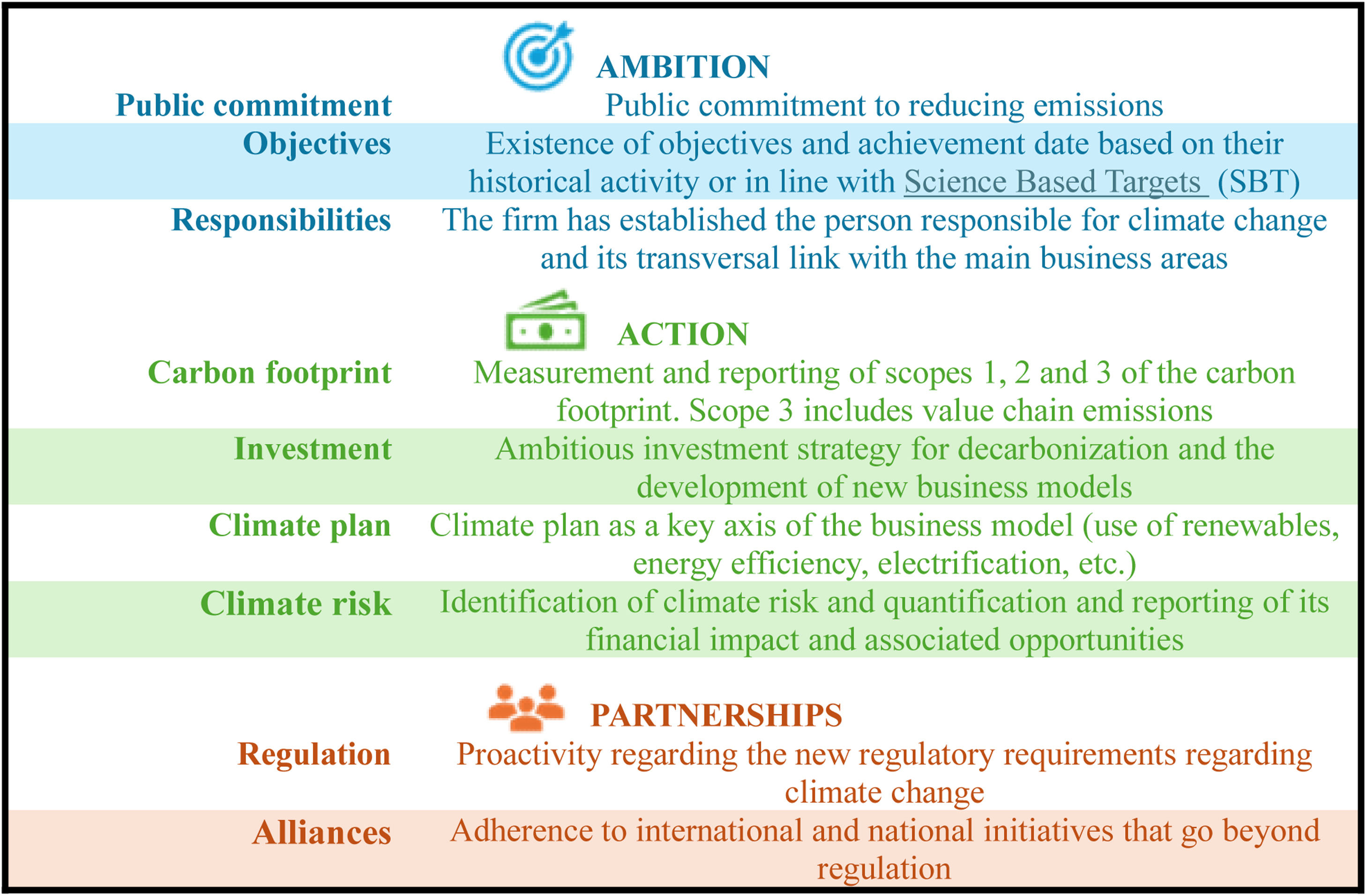

VariablesThe dependent variable DescStr corresponds to a composite indicator that takes values between 0 and 18 to identify the level of development of a company's decarbonisation strategy. Fig. 2 presents its conceptualisation and the items used in its construction.

The independent variable IInv corresponds to the voting rights held by institutional investors with a stake of 5 % or more of the capital. Furthermore, to test hypothesis H2, following Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023), we present additional models in which institutional investors are disaggregated according to the time horizon of their investment and its strategic or non-strategic nature. More specifically, following the proposal of Brossard et al. (2013), García-Sánchez et al. (2020a), and Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2024), the classification of institutional investors according to their investment horizon leads to the variable LTInv, which refers to long-term institutional investors and includes the government, family firms, and pension and endowment funds, and the variable STInv, which refers to short-term institutional investors and includes financial institutions and cross-holdings. Alternatively, in line with Bueno-García et al. (2022), we consider government institutions, cross-holdings and family firms as strategic investors (StrInv) and pension or endowment funds and financial institutions as financial investors (FinInv).

The mediating variable CGov, which represents the strength of climate governance according to Bui et al. (2020), Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2024), García-Sánchez et al. (2023a) and Albitar et al. (2023), is a score taking values between 0 and 5, based on the existence of (1) a sustainability committee, (2) an ESG compensation policy, (3) executive compensation linked to ESG performance, and (4) the availability of public information on climate change prepared according to international standards and (5) assured by an external assurance provider.

The control variables control for the firm's resources and capabilities related to size (fsize), reliance on external financing (lev), return on assets (ROA), dividend policy (div), and tangible and intangible investments (capex, R&D, adv). We also control for various aspects related to board effectiveness, e.g. size (bsize), activity (bmeet), independence (bindep), diversity (bwomen) and CEO duality (duality). The variable UncT takes the value 1 for the period 2020 to 2022, otherwise 0, to control for the disruptive effects of the COVID19 pandemic and the invasion of the Ukraine. In addition, we control for the European constitutional context with the dummy ‘EU’ because of the EU's strong commitment to the environment (García-Sánchez et al., 2023c). Finally, we include ordinal variables to control for sector, country and time effects.

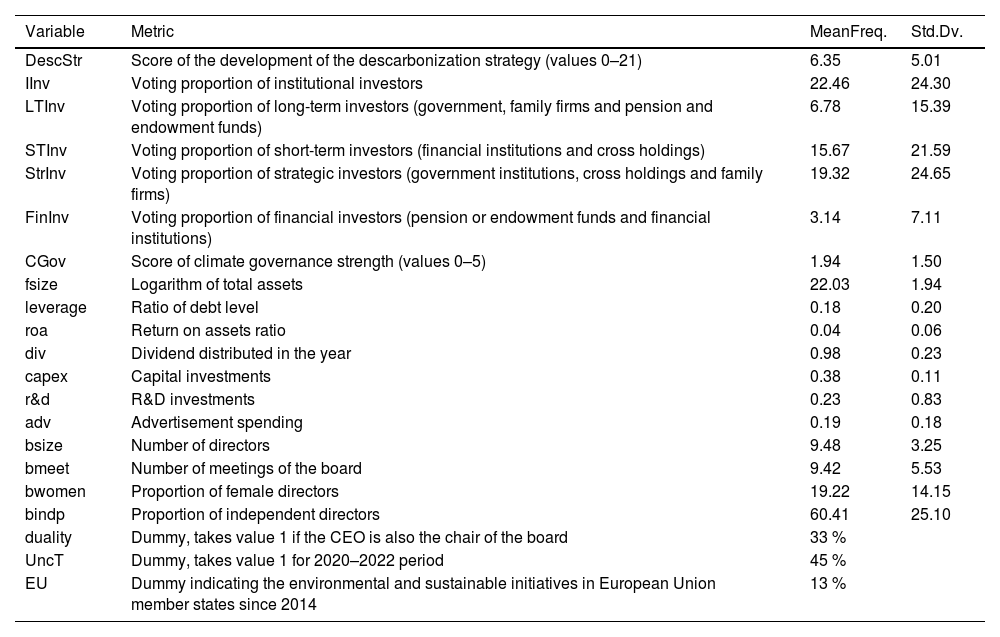

ResultsDescriptivesTable 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables used to test the research hypotheses. It can be seen that the level of development of the company's decarbonisation strategy has an average score of 6 out of a possible 18 points, representing a level of progress of 33 %. Institutional investors hold 22.46 % of the voting rights. The strength of climate governance is also limited, with an average score of 2 out of 5.

Variables.

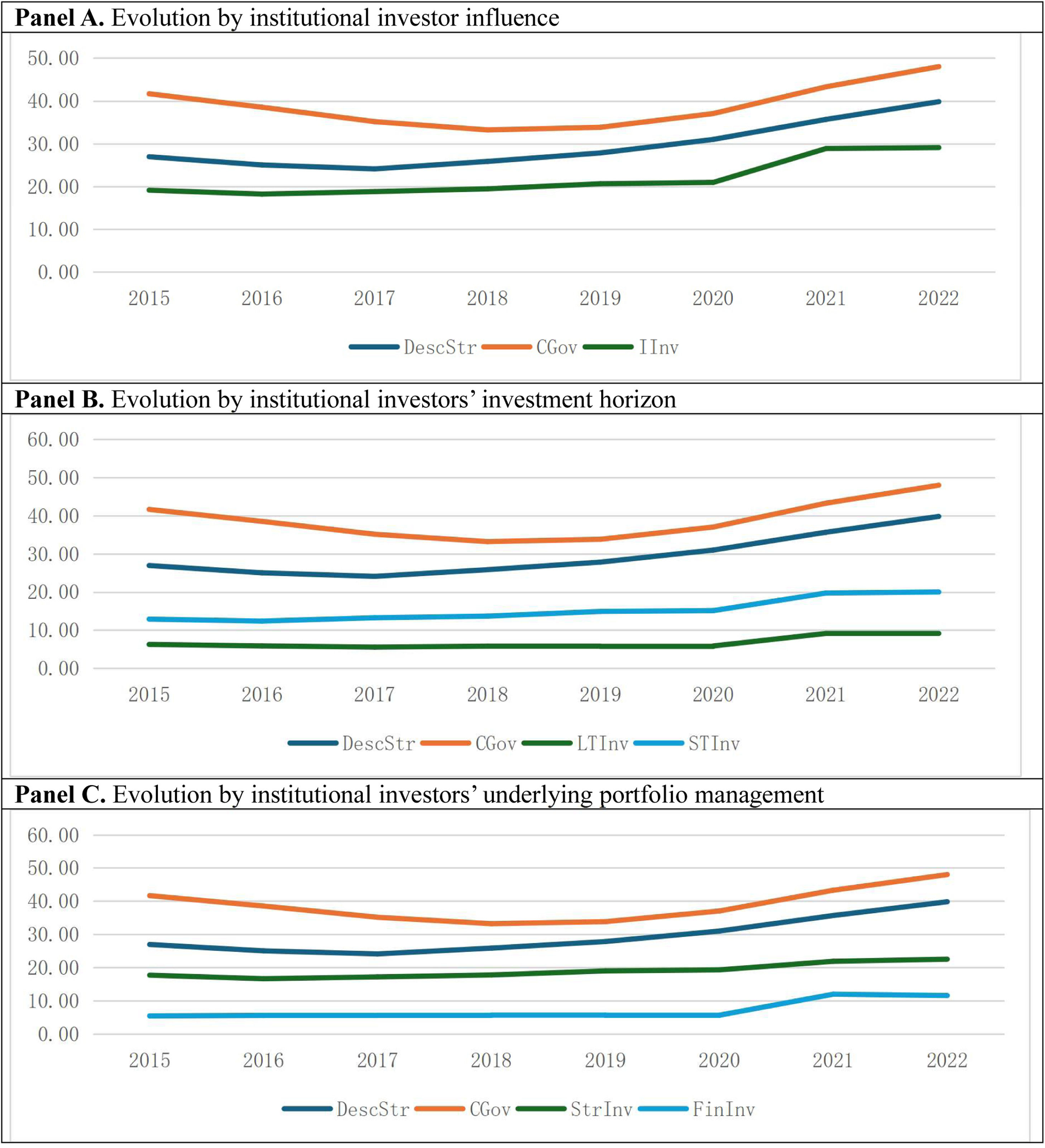

Panels A, B and C of Fig. 3 show the temporal evolution of the degree of development of a company's decarbonisation strategy in terms of its relative value, the strength of climate governance and the degree of influence of institutional investors.

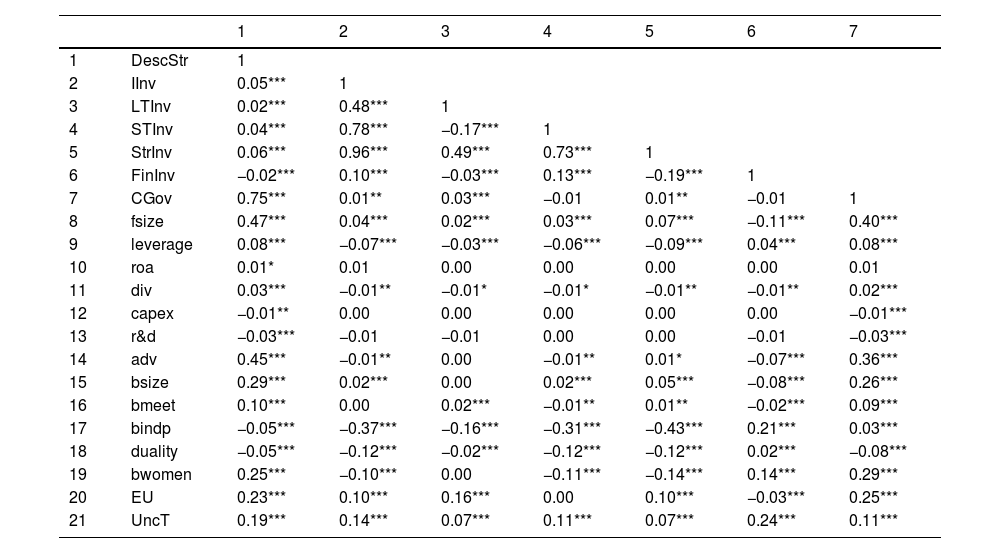

Table 2 shows the bivariate correlations, which allow us to determine the absence of collinearity problems from an analysis of the coefficients.

Bivariate correlations.

*** p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05. * p < 0.1.

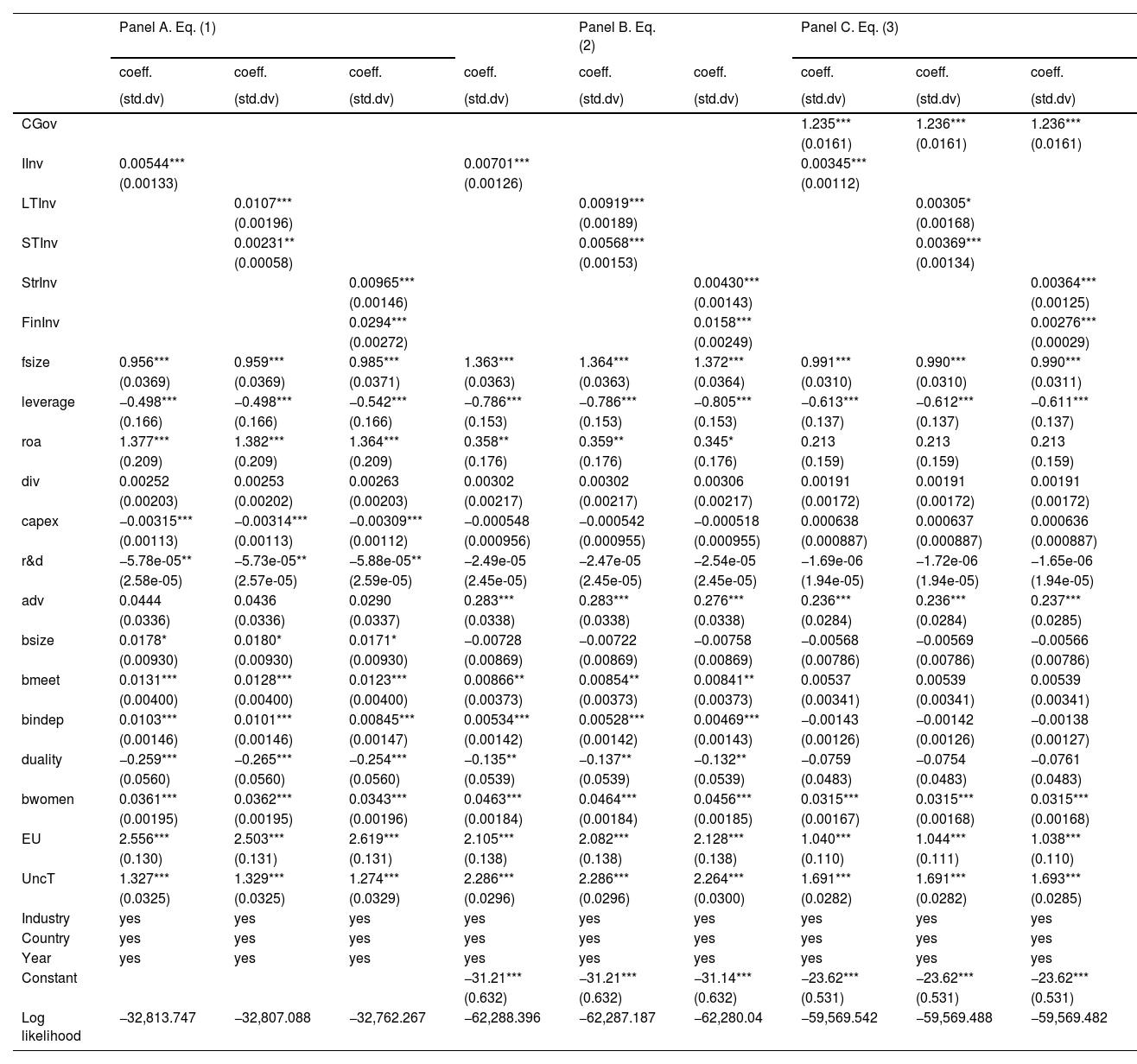

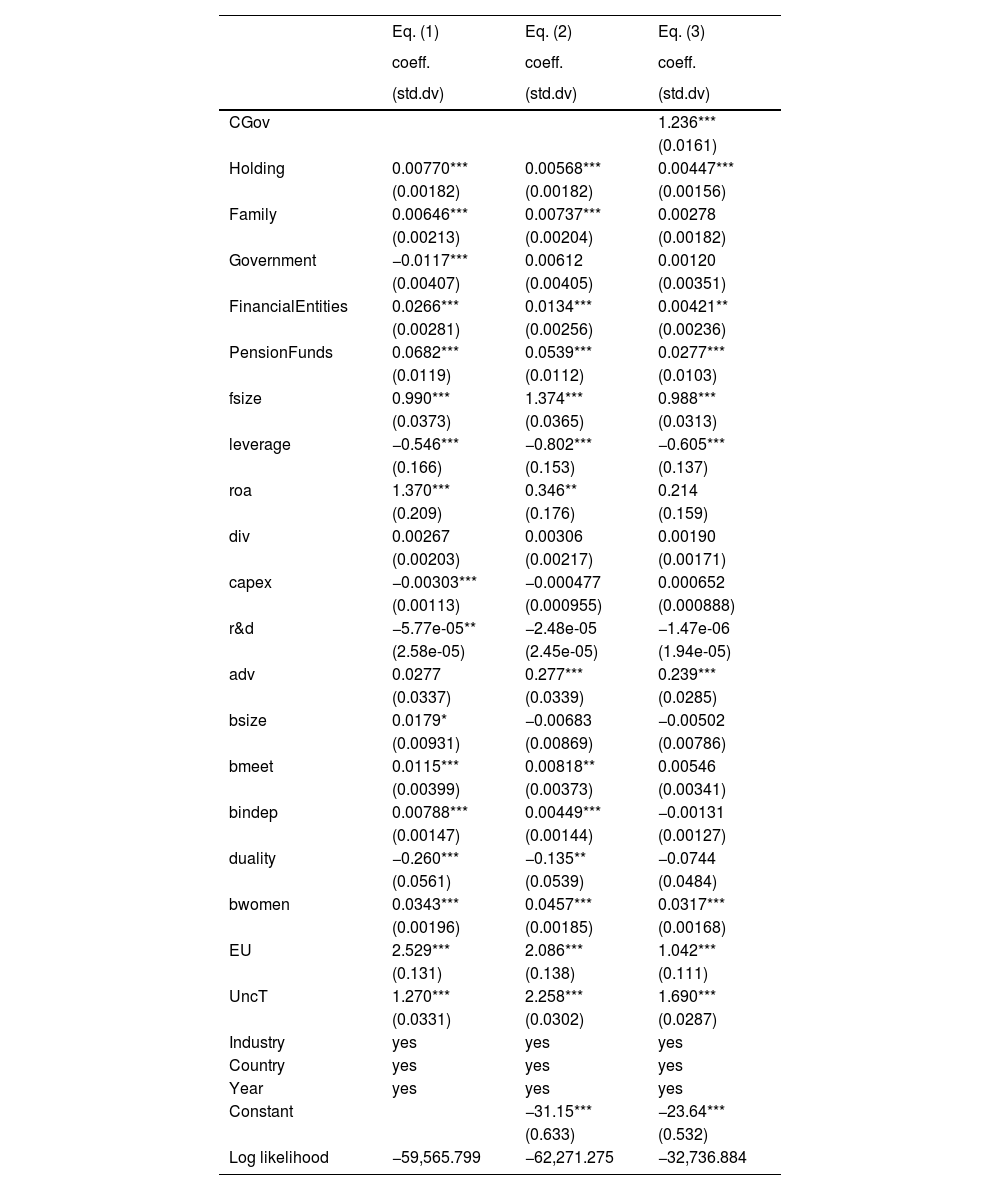

Table 3 presents the results of the estimation of the three equations proposed to test the research hypotheses. The results of all the equations are presented for the basic model, which takes into account the overall influence of institutional investors, and their breakdown according to the two classifications of institutional investors considered in this study.

Main results.

| Panel A. Eq. (1) | Panel B. Eq. (2) | Panel C. Eq. (3) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | |

| (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | |

| CGov | 1.235*** | 1.236*** | 1.236*** | ||||||

| (0.0161) | (0.0161) | (0.0161) | |||||||

| IInv | 0.00544*** | 0.00701*** | 0.00345*** | ||||||

| (0.00133) | (0.00126) | (0.00112) | |||||||

| LTInv | 0.0107*** | 0.00919*** | 0.00305* | ||||||

| (0.00196) | (0.00189) | (0.00168) | |||||||

| STInv | 0.00231** | 0.00568*** | 0.00369*** | ||||||

| (0.00058) | (0.00153) | (0.00134) | |||||||

| StrInv | 0.00965*** | 0.00430*** | 0.00364*** | ||||||

| (0.00146) | (0.00143) | (0.00125) | |||||||

| FinInv | 0.0294*** | 0.0158*** | 0.00276*** | ||||||

| (0.00272) | (0.00249) | (0.00029) | |||||||

| fsize | 0.956*** | 0.959*** | 0.985*** | 1.363*** | 1.364*** | 1.372*** | 0.991*** | 0.990*** | 0.990*** |

| (0.0369) | (0.0369) | (0.0371) | (0.0363) | (0.0363) | (0.0364) | (0.0310) | (0.0310) | (0.0311) | |

| leverage | −0.498*** | −0.498*** | −0.542*** | −0.786*** | −0.786*** | −0.805*** | −0.613*** | −0.612*** | −0.611*** |

| (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.153) | (0.153) | (0.153) | (0.137) | (0.137) | (0.137) | |

| roa | 1.377*** | 1.382*** | 1.364*** | 0.358** | 0.359** | 0.345* | 0.213 | 0.213 | 0.213 |

| (0.209) | (0.209) | (0.209) | (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.176) | (0.159) | (0.159) | (0.159) | |

| div | 0.00252 | 0.00253 | 0.00263 | 0.00302 | 0.00302 | 0.00306 | 0.00191 | 0.00191 | 0.00191 |

| (0.00203) | (0.00202) | (0.00203) | (0.00217) | (0.00217) | (0.00217) | (0.00172) | (0.00172) | (0.00172) | |

| capex | −0.00315*** | −0.00314*** | −0.00309*** | −0.000548 | −0.000542 | −0.000518 | 0.000638 | 0.000637 | 0.000636 |

| (0.00113) | (0.00113) | (0.00112) | (0.000956) | (0.000955) | (0.000955) | (0.000887) | (0.000887) | (0.000887) | |

| r&d | −5.78e-05** | −5.73e-05** | −5.88e-05** | −2.49e-05 | −2.47e-05 | −2.54e-05 | −1.69e-06 | −1.72e-06 | −1.65e-06 |

| (2.58e-05) | (2.57e-05) | (2.59e-05) | (2.45e-05) | (2.45e-05) | (2.45e-05) | (1.94e-05) | (1.94e-05) | (1.94e-05) | |

| adv | 0.0444 | 0.0436 | 0.0290 | 0.283*** | 0.283*** | 0.276*** | 0.236*** | 0.236*** | 0.237*** |

| (0.0336) | (0.0336) | (0.0337) | (0.0338) | (0.0338) | (0.0338) | (0.0284) | (0.0284) | (0.0285) | |

| bsize | 0.0178* | 0.0180* | 0.0171* | −0.00728 | −0.00722 | −0.00758 | −0.00568 | −0.00569 | −0.00566 |

| (0.00930) | (0.00930) | (0.00930) | (0.00869) | (0.00869) | (0.00869) | (0.00786) | (0.00786) | (0.00786) | |

| bmeet | 0.0131*** | 0.0128*** | 0.0123*** | 0.00866** | 0.00854** | 0.00841** | 0.00537 | 0.00539 | 0.00539 |

| (0.00400) | (0.00400) | (0.00400) | (0.00373) | (0.00373) | (0.00373) | (0.00341) | (0.00341) | (0.00341) | |

| bindep | 0.0103*** | 0.0101*** | 0.00845*** | 0.00534*** | 0.00528*** | 0.00469*** | −0.00143 | −0.00142 | −0.00138 |

| (0.00146) | (0.00146) | (0.00147) | (0.00142) | (0.00142) | (0.00143) | (0.00126) | (0.00126) | (0.00127) | |

| duality | −0.259*** | −0.265*** | −0.254*** | −0.135** | −0.137** | −0.132** | −0.0759 | −0.0754 | −0.0761 |

| (0.0560) | (0.0560) | (0.0560) | (0.0539) | (0.0539) | (0.0539) | (0.0483) | (0.0483) | (0.0483) | |

| bwomen | 0.0361*** | 0.0362*** | 0.0343*** | 0.0463*** | 0.0464*** | 0.0456*** | 0.0315*** | 0.0315*** | 0.0315*** |

| (0.00195) | (0.00195) | (0.00196) | (0.00184) | (0.00184) | (0.00185) | (0.00167) | (0.00168) | (0.00168) | |

| EU | 2.556*** | 2.503*** | 2.619*** | 2.105*** | 2.082*** | 2.128*** | 1.040*** | 1.044*** | 1.038*** |

| (0.130) | (0.131) | (0.131) | (0.138) | (0.138) | (0.138) | (0.110) | (0.111) | (0.110) | |

| UncT | 1.327*** | 1.329*** | 1.274*** | 2.286*** | 2.286*** | 2.264*** | 1.691*** | 1.691*** | 1.693*** |

| (0.0325) | (0.0325) | (0.0329) | (0.0296) | (0.0296) | (0.0300) | (0.0282) | (0.0282) | (0.0285) | |

| Industry | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Country | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Year | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Constant | −31.21*** | −31.21*** | −31.14*** | −23.62*** | −23.62*** | −23.62*** | |||

| (0.632) | (0.632) | (0.632) | (0.531) | (0.531) | (0.531) | ||||

| Log likelihood | −32,813.747 | −32,807.088 | −32,762.267 | −62,288.396 | −62,287.187 | −62,280.04 | −59,569.542 | −59,569.488 | −59,569.482 |

*** p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05. * p < 0.1.

The three columns of Panel A show the results obtained for Eq. (1) when considering the overall influence of institutional investors (column 1), their classification according to their investment horizon (column 2), and according to the strategic/financial nature of their investment (column 3). We observe that the influence of institutional investors on the strength of climate governance is β1=0.00544>0, significant at the 99 % confidence level. This positive effect is confirmed for all the proposed classifications of investors, being 0.0107 and 0.00231 for institutional investors with long-term and short-term horizons respectively, and 0.00965 and 0.0294 when their classification takes into account the strategic or financial objectives of their investment. These effects are significant at a 99 % confidence level, except for STInv, which is significant at 95 %.

In the three columns of Panel B, we can see the results obtained in the estimation of Eq. (2) regarding the influence of institutional investors on the development of a company's decarbonisation strategy. Similarly to Eq. (1), three columns are presented according to the overall and disaggregated consideration of institutional investors. The overall influence of institutional investors is α1=0.00701. For their investment horizon, it is 0.00919 for the long-term institutional investors and 0.00568 for the short-term institutional investors. For their investment objectives, it is 0.00430 for strategic investors and 0.0158 for financial investors. All effects are significant at the 99 % confidence level, except for the effect of strategic investors, which is marginal, being only at the 90 % confidence level.

The results obtained for Eq. (3) are presented in Panel C. The first column shows that the mediating variable CGov has an effect of δ2=1.235 on DescStr at a 99 % confidence level. The independent variable IInv has an effect of δ1=0.00345, which is significant at the same confidence level. The effect of this variable is lower than that observed in the estimation of Eq. (2), i.e., α1=0.00701>δ1=0.00345>0.

Therefore, our empirical evidence confirms hypotheses H1 and H3 regarding the existence of a direct and indirect influence of institutional investors on the development of the decarbonisation strategy of the companies in which they invest. The indirect effect occurs through the mediation of the strength of climate governance. But the empirical evidence does not support hypotheses H2a and H2b, as heterogeneity within the institutional investor landscape does not shape their influence on climate-related practices.

Regarding hypothesis H1, our results support a positive relationship between institutional ownership and decarbonisation strategies in that the presence of institutional investors promotes the adoption of decarbonisation strategies. This result is consistent with previous findings by Nishitai and Kokubu (2012), Basse Mama and Mandaroux (2022), Safiullah et al. (2022), Benlemlih et al. (2023), and Kolasa and Sautner (2024) on the influence of institutional ownership on climate change initiatives and performance.

For hypotheses H2a and H2b, our results suggest that neither differences in the investment horizon nor in the objectives of institutional investors affect their influence on the adoption of decarbonisation strategies. This finding contrasts with those of García-Sánchez et al. (2020a), Safiullah et al. (2022), Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2023), Kavadis and Thomsen (2023), and Drobetz et al. (2024). This can be explained by the influence of regulatory frameworks (e.g. the EU Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth) and market and non-market incentives (e.g. carbon taxes), which could play a key role in reconciling the interests of short- and long-term institutional investors (Ameli et al., 2020; Benz et al., 2020; Atta-Darkua et al., 2023).

Regarding hypothesis H3, our results confirm that climate governance mediates a relationship between institutional ownership and corporate decarbonisation strategies by translating pressure by institutional investors into implementable corporate practices. Regarding the influence of institutional investors on climate governance, our result is consistent with Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2024), while regarding the influence of climate governance on decarbonisation strategies and initiatives, our result is consistent with Galbreath (2010), Orazalin (2020)), Luo and Tang (2021), and García-Sánchez et al. (2024). Overall, our empirical results confirm the complementary effect of internal and external corporate governance structures on climate-related initiatives observed by Kavadis and Thomsen (2023) and Aibar-Guzmán et al. (2024).

This evidence is confirmed when Eq. (3) is estimated considering the investment horizon of institutional investors (column 2) and their strategic or financial objectives (column 3). In both estimations, the coefficients are positive and significant at the 99 % confidence level, except in the case of long-term investors, which is marginally econometrically significant (90 % confidence level).

With respect to the control variables, the results show that the highest development of decarbonisation strategies occurs in larger, more profitable and less indebted companies. These companies are also characterised by more active boards, whose meetings are not chaired by the CEO, and by a higher presence of women. These variables also explain climate strength. These findings are consistent with those of García-Sánchez et al. (2023b), who also found a positive influence of firm size, board activity and board gender diversity on climate technology innovation.

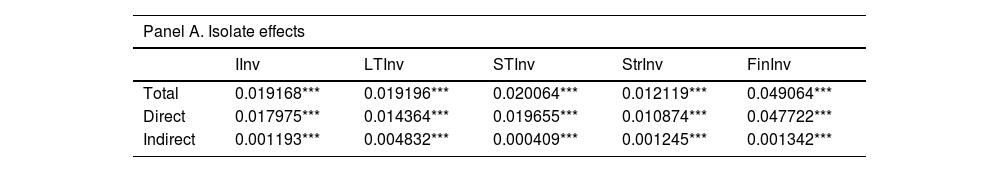

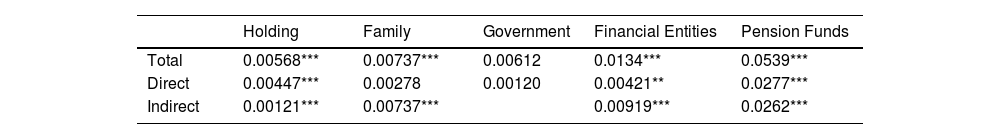

Table 4 shows the total, direct and indirect effects of the different variables used to measure and represent the presence of institutional investors in the shareholding, as well as their classification based on the time horizon of their investment and their underlying portfolio management objectives. When interpreting these effects, it is important to understand that the total effect determines the quantitative change for two companies that differ by one unit in terms of the presence of institutional investors in the decarbonisation strategy. The direct effect estimates how two companies that differ by one unit in the presence of institutional investors, but have similar climate governance practices, change in their decarbonisation strategy. The indirect effect estimates how two companies differ in DescStr through the sequence of causal steps in which the presence of institutional investors affects climate governance, which in turn affects decarbonisation strategy.

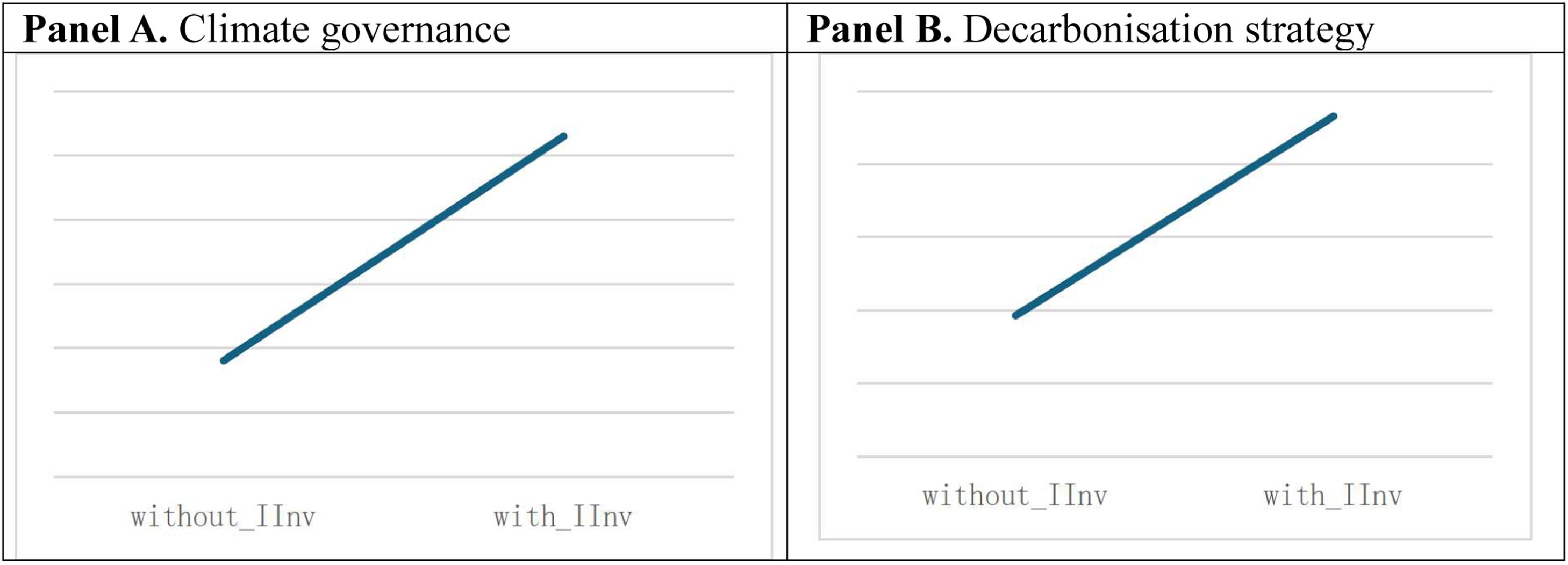

Fig. 4 also shows Trends in decarbonisation strategy and climate change governance according to the presence or absence of institutional investors. Panel A presents the case of climate governance, while Panel B does the same for decarbonisation strategies.

Supplementary analysis: does the type of institutional investor matter?Several studies, such as García-Sánchez et al. (2020b), have observed that the influence of different institutional investors on investment in eco-innovation projects does not always correspond to the academic expectations of their grouping according to the investment horizon. In this respect, Safiullah et al. (2022) argue that grouping institutional investors into broad categories to examine their effect on carbon emissions provides an incomplete picture and call for a more comprehensive examination of the effect of different types of institutional investors on carbon emissions reduction.

Therefore, in order to complement the previous evidence and provide a more accurate understanding of how heterogeneity in institutional ownership affects corporate sustainability (Velte, 2023), we proceeded to estimate the three previous equations with the separate consideration of each type of institutional investor: cross holdings, family firms, financial institutions, government institutions, and pension or endowment funds.

Table 5 shows the findings of this more fine-grained analysis, which confirm the hypotheses of direct and indirect influence of institutional investors, but only for cross-holdings, financial institutions and pension or endowment funds. The total, direct and indirect effects are in Table 6. These results are consistent with those obtained by Benz et al. (2020) for mutual funds, pension funds and insurance companies, although they contrast with the findings of Safiullah et al. (2022), who found that banks and insurance companies have no significant effect on corporate carbon emissions, while pension funds and endowments have a negative effect on carbon emissions.

Individual effect of institutional investors.

| Eq. (1) | Eq. (2) | Eq. (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| coeff. | coeff. | coeff. | |

| (std.dv) | (std.dv) | (std.dv) | |

| CGov | 1.236*** | ||

| (0.0161) | |||

| Holding | 0.00770*** | 0.00568*** | 0.00447*** |

| (0.00182) | (0.00182) | (0.00156) | |

| Family | 0.00646*** | 0.00737*** | 0.00278 |

| (0.00213) | (0.00204) | (0.00182) | |

| Government | −0.0117*** | 0.00612 | 0.00120 |

| (0.00407) | (0.00405) | (0.00351) | |

| FinancialEntities | 0.0266*** | 0.0134*** | 0.00421** |

| (0.00281) | (0.00256) | (0.00236) | |

| PensionFunds | 0.0682*** | 0.0539*** | 0.0277*** |

| (0.0119) | (0.0112) | (0.0103) | |

| fsize | 0.990*** | 1.374*** | 0.988*** |

| (0.0373) | (0.0365) | (0.0313) | |

| leverage | −0.546*** | −0.802*** | −0.605*** |

| (0.166) | (0.153) | (0.137) | |

| roa | 1.370*** | 0.346** | 0.214 |

| (0.209) | (0.176) | (0.159) | |

| div | 0.00267 | 0.00306 | 0.00190 |

| (0.00203) | (0.00217) | (0.00171) | |

| capex | −0.00303*** | −0.000477 | 0.000652 |

| (0.00113) | (0.000955) | (0.000888) | |

| r&d | −5.77e-05** | −2.48e-05 | −1.47e-06 |

| (2.58e-05) | (2.45e-05) | (1.94e-05) | |

| adv | 0.0277 | 0.277*** | 0.239*** |

| (0.0337) | (0.0339) | (0.0285) | |

| bsize | 0.0179* | −0.00683 | −0.00502 |

| (0.00931) | (0.00869) | (0.00786) | |

| bmeet | 0.0115*** | 0.00818** | 0.00546 |

| (0.00399) | (0.00373) | (0.00341) | |

| bindep | 0.00788*** | 0.00449*** | −0.00131 |

| (0.00147) | (0.00144) | (0.00127) | |

| duality | −0.260*** | −0.135** | −0.0744 |

| (0.0561) | (0.0539) | (0.0484) | |

| bwomen | 0.0343*** | 0.0457*** | 0.0317*** |

| (0.00196) | (0.00185) | (0.00168) | |

| EU | 2.529*** | 2.086*** | 1.042*** |

| (0.131) | (0.138) | (0.111) | |

| UncT | 1.270*** | 2.258*** | 1.690*** |

| (0.0331) | (0.0302) | (0.0287) | |

| Industry | yes | yes | yes |

| Country | yes | yes | yes |

| Year | yes | yes | yes |

| Constant | −31.15*** | −23.64*** | |

| (0.633) | (0.532) | ||

| Log likelihood | −59,565.799 | −62,271.275 | −32,736.884 |

*** p < 0.01. ** p < 0.05. * p < 0.1.

This study examines the influence of institutional ownership on a firm's decarbonisation strategy by analysing whether its direct influence is complemented by a mediated effect via the development of climate governance structures within the company. The results for a sample of 4956 MNCs for the period 2015–2022 show a positive direct and indirect effect of institutional investors on the development of the decarbonisation strategy of the company they have invested in, with the latter occurring through the mediation of the strength of climate governance, channelling the pressure of institutional investors into the formulation of corporate climate strategies. Neither effect depends on the investment horizon (long-term or short-term) and objectives (strategic or financial) of the institutional investors, although we observe that some types of institutional investors (cross-holdings, financial institutions and pension funds) improve MNCs’ climate-related governance mechanisms and promote more robust decarbonisation strategies.

This research extends the existing knowledge of the influence of institutional ownership on corporate climate proactivity and the mechanisms through which this influence translates into substantive climate strategies, thereby offering a nuanced understanding of how institutional pressures shape corporate responses to the global challenge of climate change. We have shown that, regardless of their investment horizon and the nature of their investment objectives, institutional investors are effectively acting as catalysts for a global transition to a sustainable economy by directly and indirectly driving corporate decarbonisation efforts. We also show that climate governance –operationalised through sustainability committees, ESG-linked executive compensation and transparent, assured climate disclosure– mediates the relationship between institutional ownership and decarbonisation strategies by ensuring that the influence of institutional investors is effectively channelled into sustainable corporate action. This mediating effect highlights the interconnected nature of governance, investment and sustainability, and illustrates how institutional investors’ engagement and robust governance structures can collectively drive the transition to a low-carbon economy. Indeed, climate-orientated governance mechanisms not only facilitate the adoption of decarbonization strategies but also amplify the influence of institutional investors, creating a virtuous cycle of accountability and climate action.

From a theoretical perspective, our findings support agency theory as a compelling theoretical lens through which to analyse the influence of institutional investors on corporate climate action and the practical dynamics of internal and external corporate governance mechanisms. We show that, by mitigating agency conflicts, institutional investors drive the adoption of decarbonisation strategies and climate governance mechanisms, thereby aligning corporate practices with the imperatives of a low-carbon economy. At the same time, climate governance mechanisms also help to address principal-agent conflicts and provide the structural basis for climate action by amplifying the influence of institutional investors to ensure that their advocacy translates into meaningful progress on decarbonisation.

From a practical perspective, by highlighting how institutional investors are catalysing corporate decarbonisation strategies and strengthening climate governance, our research findings can provide useful insights for companies, regulators, investors and society at large. For companies, the evidence underscores the importance of establishing robust climate governance mechanisms that are aligned with the expectations of institutional investors. MNCs that adopt such mechanisms not only increase their resilience to climate-related risks, but also attract capital and enhance their reputation in increasingly environmentally conscious global markets (López-Cabarcos et al., 2024). In this way, as climate risks and stakeholder expectations continue to evolve, the role of climate governance as a mediator will remain pivotal in shaping corporate responses to the global challenge of decarbonisation. Furthermore, the interplay between institutional investors and climate governance underscores the importance of integrated approaches to corporate sustainability. For regulators, the demonstrated ability of institutional investors to foster internal climate governance mechanisms provides a compelling case for encouraging the ownership of institutional investors in companies and incentivising transparency and compliance with international climate reporting standards. For investors, this research confirms the effectiveness of shareholder engagement and activism in driving corporate alignment with global climate goals, and suggests that institutional investors can maximise their portfolios by prioritising companies with robust climate governance structures, mitigating financial risk while accelerating systemic progress towards decarbonisation. Finally, for society at large, by highlighting the link between investor pressure and corporate climate action, these findings underscore the central role of financial capital in the global transition to a low-carbon economy and suggest that closer collaboration between investors, regulators and civil society could accelerate the implementation of the solutions needed to effectively mitigate climate change.

While this research makes a valuable contribution to the literature, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. Firstly, the analysis focuses on MNCs with high levels of ESG data availability, potentially biasing the results towards companies with greater visibility and resources. This limits the generalisability of the findings to smaller companies or those operating in less transparent markets, such as emerging markets (López-Cabarcos et al., 2024). Second, while the model identifies the direct and indirect influence of institutional investors, it does not fully account for how they exert this influence, i.e. whether they resort to "exit strategies" or use their "voice" through the exercise of voting rights and/or active engagement in corporate governance.

Several avenues for future research building on these findings can be suggested. Future studies could examine how the interaction between institutional ownership and climate governance is different in carbon-intensive sectors, such as energy and transport, than it is in low-emission sectors. They could also explore the extent to which different regulatory frameworks, such as carbon taxation or green finance policies, shape the relationship between institutional ownership and firms' decarbonisation strategies. Finally, future research could analyse the channel through which institutional investors exert their influence, or extend the analysis to assess how changes in the composition of institutional investors (e.g. the growth of ESG-focused funds) influence the adoption and implementation of decarbonisation strategies over time.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIsabel-María García-Sánchez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Cristina Aibar-Guzmán: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. M.Luisa López-Pérez: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Beatriz Aibar-Guzmán: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

None

Open access publishing facilitated by Universidad de Salamanca.