As the main objective of a low-carbon transition policy is to achieve green and sustainable development and since employment is related to people's livelihoods, will the low-carbon transition affect employment? Based on data from 2000–2022 for prefecture-level cities and above, we use in this paper a multiperiod difference-in-difference approach to assess the employment impacts of two different low-carbon transition policies: the low-carbon city pilot (LCCP) and the carbon emissions trading pilot (CETP). We found that both the LCCP and the CETP have positive effects on urban employment and that the marginal utility of the CETP on employment is greater than that of the LCCP. From the perspective of green sustainability, this paper reveals that the two low-carbon transition policies (LCTPs) increase urban employment through three green mechanisms: the green factor input expansion effect, the green technology creation effect and the green product demand effect. Both LCTPs have distinctly different and complementary employment impacts in different sectors, regions, and cities of different scales. The synergies between the LCTPs and data factors have a more obvious marginal effect on “stabilizing employment” and “stabilizing growth”. This paper's findings provide empirical evidence to better understand the relationship between sustainable development and employment.

The global climate crisis is a serious issue today, and the frequent occurrence of extreme weather events has caused considerable losses to human life and property, posing a severe threat to sustainable development worldwide (Bai et al., 2023; Borck & Mulder, 2024). The Emissions Database for Global Atmospheric Research (EDGAR) report shows that global greenhouse gas emissions trends have shown an increase since the beginning of the 21st century, mainly due to increased CO2 emissions from China and other emerging economies. 2025 Emerging Economies CO2 Emissions report shows that rising energy demand is driving a strong rebound in fossil energy-related carbon emissions in some countries. In 2022, carbon emissions from Myanmar, Pakistan, Cambodia, India, Laos, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, Turkey, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, and China are 28.4mt, 181.1mt, 16.2mt, 2918.8mt, 20.2mt, 134.7mt, 880.5mt, 258.3mt, 396.5mt, 230.8mt, 211.7mt, and 9845.4mt. In this context, China is committed to integrating climate governance into the overall situation of national development. Actively addressing climate change is not only a crucial strategy for China's development but also an important opportunity to promote the transformation of the economy into a new development model (Song et al., 2025), as China's contribution as a responsible power to global climate governance through Chinese wisdom and programs is well known. China is in an important period of comprehensively building a socialist modernization country, and energy demand remains strong; therefore, it is imperative to effectively control GHG emissions and realize a carbon-neutral transition of the economy.

Since 2010, China has adopted two pilot policies aimed at controlling GHG emissions, with the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) issuing the Notice on Launching the Pilot Work of Low-Carbon Provinces, Regions and Cities and the Pilot Work of Carbon Emissions Trading in July 2010 and October 2011. The LCCP was implemented in three batches, expanding from five provinces and eight cities in the first batch to 29 provinces, autonomous regions and municipalities in the second batch and then to 45 cities approved in the third batch. In 2011, the country began deploying the CETP, the first batch of cities authorized to conduct pioneering carbon trading work in seven regions and cities. In 2013, the seven pilot areas began online trading one after another. In 2016, Fujian started the carbon trading market as the second batch of pilot areas. Although the former relies on administrative means to lower CO2 emissions and the latter utilizes market mechanisms to do so, the fundamental objectives of both pilot policies are the same, i.e., to curb and reduce CO2 emissions and to foster a sustainable, low-carbon development model. Inevitably, realizing these LCTPs will reconfigure factors of production and shift economic development from factor-driven to technological innovation-driven (Wang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2025); however, this transformation has a profound influence on the allocation of resources and production patterns in various industries, triggering industrial structural adjustment and changes in the labor market (Yamazaki, 2017). As Schumpeter's innovation theory points out, economic transformation and technological innovation are often accompanied by “creative destruction”, and their impact is not only limited to the upgrading of the industrial structure but also involves a profound change in the employment structure (Acemoglu, 2002).

Employment is related not only to the overall economic situation but also to the well-being of people's livelihoods and is an essential factor for economic growth and social stability. Full employment is an important prerequisite for the maximization of social welfare, which can both promote the growth of consumer demand and enhance the resilience of economic development. The Chinese Government has always attached great importance to employment and has always placed employment at the forefront of its work, making full and high-quality employment a priority goal of economic and social development, and implementing a model of governmental responsibility for employment at all levels. The current complex and severe foreign situation and the impact of multiple expected pressures have led to a more severe employment situation. Coupled with the transformation to low carbon, the shrinkage of traditional industries and the rise of green industries, whether the reallocation of resources brought about by the optimization of the industrial structure will have an adverse effect on employment is a realistic question we are facing. Therefore, it is worthwhile to study the issue of realizing the coordinated development of green transformation and “stabilizing employment”. Chief among these questions is how China's LCTPs, already in place for more than a decade, have impacted employment. If the LCTPs affect employment, through what mechanism do they do so? Furthermore, do the policies affect employment differently in different sectors, regions, and cities of various sizes? As a new factor of production, data are generating far-reaching impacts on economic and social development (Brynjolfsson &McElheran, 2016;Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020; Moravec et al., 2025; Zhu et al., 2025). Can the combination of low-carbon policies and data have a synergistic effect on “stabilizing employment”? At present, China's economic development is facing multiple impacts of unexpected factors and is in the critical period of realizing the goal of “double carbon”; therefore, how to address the balance between green and low-carbon transformation and “stabilizing employment” is of vital practical significance. This paper evaluates the employment effects of the LCCP and CETP in the long run based on city data from 2000 to 2022 using a multiperiod DID approach.

The main marginal contributions of this study are as follows: first, we examined the influences of the LCCP (administrative regulation) and CETP (market mechanism) on employment and found that the roles played by the two pilot policies in various regions and industries are both different and complementary, so empirical evidence can be provided for better handling the roles of the market mechanism and administrative regulation in resource allocation to establish a theoretical basis of a high-level socialist market economy. Second, we analyzed the three mechanisms by which the two LCTPs affect employment, namely, the employment expansion mechanism of green factor inputs, the employment-driven mechanism of technological innovation and the employment-creation mechanism of green product demand, and empirically tested the existence of the effects of the above mechanisms on employment. Third, as a new and extensive factor of production, data also have a powerful impact on employment, so we integrated the data pilot policy with the LCTPs to test the “stabilizing employment” and “stabilizing growth” effects of the “dual-pilot” policy. Fourth, in terms of sample selection, most studies were conducted by 2019, but since 2020, with the utilization of digital technology in various industries, a considerable change in the employment landscape has taken place. This paper provides a systematic assessment of and empirical evidence for the employment impacts of the LCTPs over a longer time span (2000–2022), which is useful for understanding the longevity and effectiveness of low-carbon policies.

Literature reviewRelevant studies on the LCTPs in relation to employmentOne view was that the LCTPs could contribute to increased employment. Using an economic-energy-environmental model, Lehr et al. (2012) evaluated the active influence of green investments on employment in Germany. Markandya et al. (2016) reported that the transformation of the EU's energy mix has significantly increased employment opportunities in both the short and medium terms. Li et al. (2022) found that more than 8000 jobs could be created by RES power plant projects using input-output modeling. Zhang et al. (2024), based on Chinese data from 2007- 2019, reported that LCCP contributed markedly to employment in cities and firms and that such positive impacts varied according to various types of enterprises. Bernardo and D'Alessandro (2016) introduced a modified Lotka-Volterra model in a standard growth framework to compare the outcomes of different combinations of three carbon abatement strategies that can improve energy efficiency. Expanding the deployment of RE directly reduces CO2 emissions, and green investments, in order to satisfy emission reduction targets, can increase employment and labor shares.

Several studies have indicated that environmental regulations have a significant dampening effect on employment (Ferris et al., 2014; Li & Li, 2024; Liu et al., 2021). Yamazaki (2017) used Canada's carbon tax policy implemented in 2008 as an example and found that employment across industries showed obvious differences in sensitivity to the carbon tax, with employment in carbon-related industries and the traded industrial sector markedly lower, whereas employment in the cleaning services sector increased due to the carbon tax, suggesting that there is a marked difference in the extent to which the size of employment in each industry reflects the carbon tax. Walker (2011) reported that environmental regulations resulted in a decrease in firm employment. Yip (2018) estimates the carbon tax's consequences for the UK job market using individual household data and discovered that the policies' adoption had led to a 1.30 % drop in overall employment in the UK. Raff and Earnhart (2019) and Liu et al. (2017) analyzed the impact of environmental regulations on firms' labor demand based on microenterprise data and concluded that environmental regulations severely dampen the labor demanded by firms. Some scholars have also used macro data analysis to argue that environmental protection laws have a negative impact on labor demand in China, while environmental regulation contributes to the improvement of environmental quality and results in greater loss of overall employment, leading to a decline in employment (Li & Li, 2024; Liao & Zhang, 2024).

Other studies have found that environmental protection policies have no or minimal impact on employment (Morgenstern et al., 2002). Martin et al. (2014) assessed the effect of the UK carbon tax on manufacturing employment in 2011 and reported that despite the policy's lowering of energy intensity, it did not affect jobs or enterprise receipts. Ferris et al. (2014) and Hafstead and Williams (2018) examined two different U.S. environmental regulatory policies on the amount of labor demanded in different industries. Ferris et al. (2014) focused on employment changes in energy-intensive power plants, whereas Hafstead and Williams (2018) focused on changes in labor demand across multiple industries. Both studies found that environmental regulation did not significantly change industry labor demand and led to a reallocation of labor across industries. Marin and Vona (2019) examined employment in several industrial sectors in European countries over the period 1995–2011 and found that firms replace manual laborers with technicians. To further confirm this finding, Marin and Vona (2021) used data on manufacturing in France from 1997 to 2015 and found that firms cope with rising energy prices by increasing the capital-to-labor ratio but that there is no significant long-run shift in the demand for labor from manual workers to technicians.

Economic impacts of low-carbon transition policiesFirst, studies have been conducted on the energy conservation and abatement effects of LCTP. Some literatures analyze the results of low-carbon city policies on carbon emissions, and on urban energy efficiency and eco-efficiency (Yu et al., 2021; Song et al., 2020), the PCET effectively reduces carbon emissions. Some literature has analyzed the association of CETP with energy use efficiency, and transformation of energy consumption structure (Hong et al., 2022; Jiang et al., 2022), found that the CETP had performed well in improving and increasing the efficiency of energy utilization. Second, some scholars have analyzed the impact of LCCP on enterprise TFP, green technology innovation from a micro perspective used enterprise data (Chen et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2021); A few scholars have explored the relevance of CETP to the transition of the economy, the transformation of the industrial structure of the manufacturing industry into a green one, the alleviation in poverty of the rural population, etc., either from a macro perspective or from an industrial perspective (Zhang et al., 2020). Other scholars explored the potential benefits of CETP on technological innovation and spillover effects of corporate innovation, corporate productivity, etc., at the micro level (Wu et al., 2022).

In summary, existing studies have mainly discussed the carbon reduction impact of the LCTPs and their effects on energy efficiency, urban green development, industrial transformation, innovation, etc. The existing research results provide the theoretical basis for this work. Few studies have explored the effects of the LCTPs on employment from both administrative and market perspectives. First, since China's LCCP and CETP were implemented almost simultaneously, although both pilot policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions and realizing green and sustainable development, they differ greatly in their intrinsic attributes and theoretical basis; thus, ignoring either of the pilot policies will not allow for an objective and accurate assessment of the real effect of their impact on employment. Second, in terms of research content, the discussion in the current literature still remains focused mainly on environmental and economic impacts, with relatively few studies on social effects. To achieve Chinese-style modernization, we should consider not only the economic and environmental benefits of the policy but also the social benefits. Third, while China is building a high-level socialist market economy, we should be more concerned with the market-oriented policies' impacts, but the current literature lacks studies on the CETP, and the samples are mostly at the provincial level. In contrast, the two pilot policies were implemented mainly at the city level, and the data at the regional level cannot provide enough detailed information. Although some studies have explored the effect of the LCCP on employment at the corporate level, there are limited data on corporations participating in the CETP market. Therefore, this essay examines the effects of the LCCP and CETP on urban employment based on data from prefecture-level cities; moreover, we deeply analyze its mechanism from the perspective of microlevel behavior and the synergistic effect of the combination of the LCTPs and data on “stabilizing growth” and “stabilizing employment”.

Theoretical process and research hypothesesEmployment outreach mechanisms for green factor inputsThe LCCP has increased the importance of relevant city departments, so they will increase subsidies and tax incentives for enterprises to clean, low-carbon and other green projects and impose administrative penalties on enterprises with excessive carbon emissions. Companies will aim to maximize profits and increase green investments proactively. The mechanism of LCCP uses administrative means to drive enterprises to increase green investment. Enterprises facing the supervision of regulatory authorities, in compliance with regulatory standards, inevitably need to increase their green investments to control and reduce CO2 emissions (Zhao et al., 2025). Enterprises also have to face the supervision of the public and media, especially listed enterprises, to avoid negative public opinion on the enterprise caused by carbon emissions, the reputation and image of the company will be affected, which in turn will affect the interests of the company, based on which the company will also take the initiative to increase green investment (Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). CETP Harnessing Market Mechanisms to Promote Enhanced Green Investment by Businesses: the target of enterprises is to maximize profits, and in the production process, if carbon emissions exceed the standard, enterprises must purchase carbon emission rights to continue production, which definitely will bring about higher production costs. Conversely, by engaging in green production, companies can either reduce their carbon emissions or earn more profit by trading their remaining carbon credits on the carbon trading market. Therefore, the direct effect of the LCTPs on employment through increased green investment is manifested as follows: first, the LCTPs increase investment in clean and other green projects, such as the construction of renewable energy facilities and the renovation of urban green infrastructure, and the implementation of these projects directly creates many related jobs (Liang et al., 2025; Ren et al., 2020). Second, the LCTPs prompt high-energy-consuming and high-carbon-emitting enterprises to add green investments (Liu et al., 2021), which leads to some job restructuring in the short term, whereas the low-carbon transition of businesses generates increased demand for employment, which requires jobs in research and development, production, sales and operations. The indirect effect manifests as follows: the extension of the industrial chain leads to the expansion of employment. Increased investment in green industries can drive the relevant industry chain; for example, a new energy industry boom will drive the prosperity of upstream and downstream industries such as battery manufacturing and smart grids, indirectly creating more employment opportunities (Wang et al., 2023). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Low-carbon transition policies lead firms to increase green factor inputs and thus affect employment.

LCCP policies are targeted at cities, which will increase their financial expenditures on low-carbon research and innovation to achieve low-carbon goals, increase financial subsidies for green industries and green enterprises, and incentivize companies to engage in green technological innovations; CETP policies are directed at enterprises, which will strengthen their investment in research on energy efficiency and emission reduction technologies and engage in green technological innovations to reduce the increased costs and expenses due to excessive carbon emissions (Chen et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, under the LCCP→ governments increase R&D fiscal budget expenditures→increase subsidies to enterprises for green technological innovations and support enterprises in embarking on green technological innovations; CETP→Lowering the carbon cost of enterprises→ to maximize profits→ increase investment in green low-carbon-related R&D →green technology innovation. The two LCTPs prompt different economic agents to develop green technological innovations. The mechanism through which the LCTPs affect employment through green technological innovation is as follows: first, to achieve low-carbon goals, cities or enterprises carry out green technological innovation, which in turn requires numerous scientific researchers and technical workers, increasing the demand for high-skilled professionals and directly pulling employment(Jiang et al., 2024). Second, technology diffusion and employment-driven effects are considered. The results of technological innovation by enterprises, through technological diffusion, lead other related industries to technological progress and innovation, creating more jobs of various types and levels and generating an employment-led effect. Research by the World Bank (2012) suggests that for every US $1 added to renewable energy investments, employment in related industries doubles by 0.5–2 times.1 China's photovoltaic industry has grown with more than 4 million installation, operation and maintenance jobs driven by technology iteration (e.g., PERC cell efficiency improvement) .2 Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Low-carbon transition policies motivate firms to innovate with green technologies, which in turn affects employment.

The LCCP strengthens residents' low-carbon awareness, which leads to increased demand for green products and services (Liao & Zhang;, 2024). For example, with the enhancement of consumers' green concept and the increasing demand for new energy vehicles, companies will increase their productivity and their supply to provide consumers with more green products and services, which will drive the expansion of the neoenergy automobile industry. Consequently, more demand for green products increases the sales revenues of enterprises, and to satisfy consumer demand, enterprises expand their production scale, thus creating more employment opportunities related to green consumption (Fu et al., 2024). The growth of the green industry will drive the relevant upstream and downstream industries to expand, indirectly leading to greater demand for labor by firms in related industries, whereas greater demand for green products will directly increase demand for green intermediate products. The 95 % localization of parts in Tesla's Shanghai factory has led to the creation of more than 100,000 new jobs in the Yangtze River Delta.3 Whether it is the LCCP or CETP→enhancement of consumers' green awareness→increasing consumer demand for green products→enabling enterprises to augment their supplies of green products and driving the→development and growth of green industries, thereby→ directly or indirectly creating more jobs related to green products and services. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Low-carbon transition policies affect employment by increasing the demand for green products.

Since the LCCP and the CETP have been implemented for more than 10 years, considering the rationalization of the experimental and control group samples to allow for a systematic assessment of the employment effects of the two LCTPs over even longer time spans, we choose the period of 2000–2022 as the research interval and collected a sample of 285 cities in China at the prefecture level and above. The data for the variables in Eqs. (1) and (2) are from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook and the CSMAR. Because the LCCP was executed in three batches, three batches of LCCP impact years are set as 2010, 2013, and 2017 in this paper, where all participating cities in some provinces are considered pilot cities by default. During the study sample period, there were two batches of CETP in the pilot areas, and the two batches of CETP were identified as the impact years of 2013 and 2017, based on the time when the provinces and cities started to launch the carbon market; similarly, all cities in some of the provincial pilots were designated as pilot cities by default. Table 1 reports the low-carbon city pilot areas and carbon emission trading pilot areas.

List of pilot regions for low-carbon transition.

Note: The list of low-carbon transition pilots in the table was manually compiled by the authors.

Following the above theoretical analysis, we built the following multiperiod DID model to evaluate the employment effects of the LCTPs.

where laborit denotes the number of jobs in city i in year t, expressed as the logarithm of city employment. did1it=lccityi × lcpostt, where lccityi and lcpostt denote the city and time dummy variables for the LCCP, respectively; it is 1 if the city is subject to a policy shock in year t and 0 otherwise. Xit is a set of control variables related to city characteristics. Referring to Fu et al. (2024), we selected foreign direct investment (fdi), per capita GDP of the city (pgdp), the logarithm of the number of enterprises in the city (enter), the per capita wage level of the city (salary), the industrial structure (indus), and the size of the population of the city (people), and the above control variables are in logarithmic form. The terms μi and δt represent time-fixed and individual effects, respectively, ϕ represents another low-carbon pilot policy, whereas εit is the random error term.did2it=cetreati × cepostt, where cetreati and cepostt denote the city and time dummy variables for the CETP, respectively; it is 1 if the city starts the CETP in year t and 0 otherwise. The other variables are the same as those above. Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics of the main variables.Statistics description of the main variables.

Table 3 reports the regression results of the LCTPs on employment. First, both low-carbon policies contribute to employment at the 1 % significance level. Second, Columns (1)- (3) are the effects of the LCCP on employment, indicating that the LCCP notably promotes an increase in urban employment in all cases. While Column (2) still has a significantly positive coefficient estimate of the LCCP with the addition of control variables to Column (1), Column (3) has a coefficient estimate of the LCCP of 0.081 with the addition of the CETP to Column (2), which is a decrease of 2.8 % compared with that when the CETP is not added. Columns (4)- (6) are the effects of the CETP on employment, and the CETP contributes significantly to job creation at the 1 % level in all scenarios. Compared with that in Columns (4) and (5), the coefficient estimate of the CETP on employment with the addition of the control variable with another pilot policy in Column (6) is 0.131, which is 4.1 % lower than the coefficient estimate when considering a pilot policy alone. Consequently, considering only one pilot policy while ignoring the other leads to biased results. Finally, the coefficient value of employment from the CETP is on average 5 % higher than that of the LCCP, indicating that the marginal effect of the CETP is more pronounced.

Benchmark regression results.

Note: ***, **, and * indicate passing the 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance level tests, respectively. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. Year and city fixed effects, control variables and another pilot policy are added below unless otherwise noted. Same as below.

Satisfying the parallel trend test is the fundamental prerequisite of the DID method. Therefore, referring to the event study methodology proposed by Jacobson et al. (1993), we constructed the following equations.

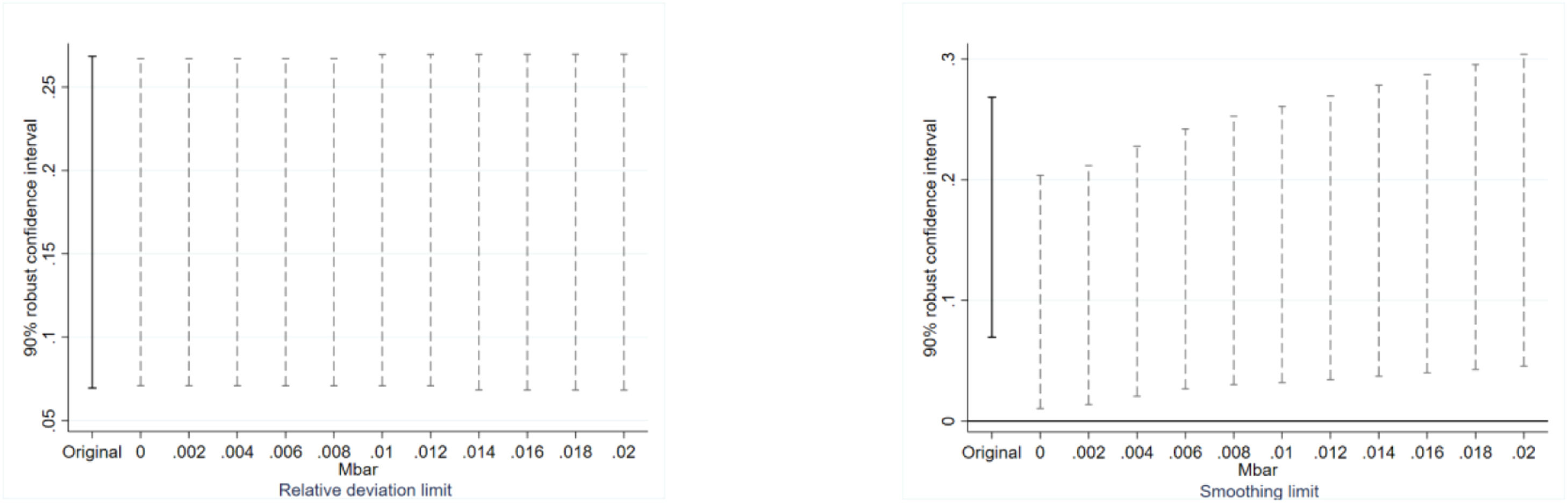

where lowpostt × lowtreati and carbonpostt × carbontreati denote dummy variables for the LCCP and CETP, respectively. If city i has executed a LCCP city or a CETP program in year t, it takes a value of 1. Otherwise, it takes a value of 0. The remaining variables have the same meaning as the symbols in the baseline regression equation. φt in Eq. (3) and ϕi in Eq. (4) are the coefficients that are the focus of this section and denote the changes in employment between pilot and nonpilot areas in year t of the LCCP and the CETP, respectively. Due to the relative incompleteness of the data before six years of policy implementation, we selected data for six years before and after the implementation of these two policies to test for parallel trends. The LCCP and CETP are highly correlated policies, thus, this study controls for the other policy separately to ensure the reliability of the results. This is illustrated in Fig. 1, with no significant difference between the coefficient estimates of (a) and (b) before the policy was implemented, the parallel trend test passes.Sensitivity test of the parallel trend hypothesisConventional pretreatment trend tests alone have the limitation of not being able to fully determine whether a parallel posttreatment trend holds. Rambachan et al. (2023) suggested that sensitivity analyses are needed to analyze postpolicy implementation results when parallel trends may be subject to different biases. First, the maximum deviation from parallel trends (Mbar) is constructed, followed by robust confidence intervals for the processed estimates corresponding to the maximum degree of bias. We refer to Rambachan et al. (2023) and set the maximum degree of bias (Mbar) to one times the standard error. Figs. 2 and 3 depict the processing results of the parallel trend sensitivity test under the relative deviation restriction and the smoothing restriction. As we can see, subject to the relative deviation limits, the employment effects of the two LCTPs are very robust in the year of implementation and remain robust even under the smoothing limit of 80 % deviation. This finding shows that both the LCCP and the CETP significantly contribute to urban employment.

Robustness testingSynthetic difference-in-differences (SDID) testIt is difficult to test the DID methodology because of its strict reliance on the “parallel trends” assumption, and the nonrandom nature of the selection of pilot districts affects the accuracy of the assessment of policy effects. Arkhangelsky et al. (2021) proposed an estimation method, the SDID method, which combines the ideas of DID and synthetic control methods and weakens the dependence on the parallel trend assumption so that the estimation results are more robust and more accurate. By determining the individual and time weights, constructing the synthetic control group and synthetic presynthesis, and then carrying out the double difference estimation, which broadens the SDID estimation's range of use and is more advantageous for robustness and estimation accuracy, we used SDID estimators to assess the employment impacts of the LCCP and CETP. As shown in Table 4, based on the SDID estimator, the mean treatment effects of both the LCCP and the CETP at the 10 % significance level or higher are 0.075 and 0.101, respectively, indicating that both LCTPs effectively contribute to the increase in employment.

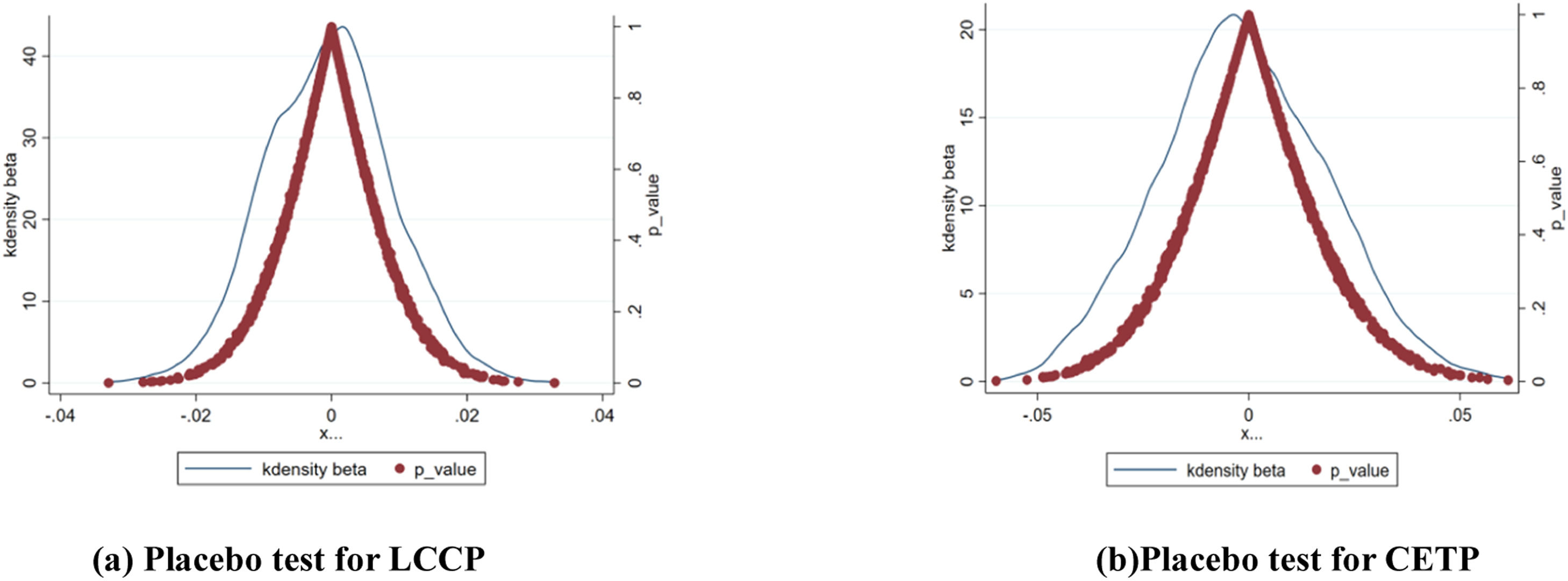

Placebo testTo further disentangle the other unknown factors from the results of the benchmark regressions, 120 cities in the study sample were randomly selected as the virtual experimental group, and the remaining cities were selected as the virtual control group. We repeated the random sampling process 1000 times, regressed the generated new dummy policy variables according to the baseline regression model, and subsequently obtained the coefficient estimates of the effects of the pilot policy on employment and their corresponding p values. As shown in Fig. 4, both the (a) and (b) estimates of the spurious regression coefficients were far from the benchmark regression coefficient values, falling near 0 and obeying a normal distribution, supporting the robustness of the benchmark regression conclusions.

PSM-DID testWe utilized the PSM-DID test in this paper to mitigate the issue of endogeneity due to sample selection bias by using control variables as sample identifying characteristics. Specifically, the probability of entering the treatment group for each sample city was predicted using logit regression; individuals in the treatment and control groups were matched using nearest-neighbor 1:1 matching, followed by DID regression on the metric data. Both the coefficient estimates of the LCCP and the CETP are significantly positive, Table 5 reports that low-carbon policies promote urban employment.

Exclusion of other policy interferencesTo preclude any interference from other contemporary policies. We have identified four related policies that may affect urban employment, namely, the “Ten Atmospheric Rules”, “Environmental Protection Interviews”, “New Energy Demonstration Cities Pilot Program” and “National Innovative Cities Pilot Program”. To address the interference of the above four policies with the baseline regression results, we exiled these policies in our benchmark regressions.

In particular, during the study sample period, the 57 high-target cities included in Atmosphere 10 take a value of 1, otherwise 0; the 73 cities interviewed for environmental protection take a value of 1, otherwise 0; the cities included in the new energy demonstration pilot take a value of 1, otherwise 0; and those selected as a national innovative pilot city take a value of 1, otherwise 0. Then, regressions are run, and the results excluding the above policies conform to the baseline results. Tables 6 and 7 report the regression results after excluding other relevant policies.

Exclusion of contemporaneous interference policy1.

Exclusion of contemporaneous interference policy2.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New energy demonstration cities | National innovative pilot cities | |||

| Low-carbon policies | did1 | did2 | did1 | did2 |

| Variables | labor | labor | labor | labor |

| 0.080⁎⁎⁎ | 0.134⁎⁎⁎ | 0.098⁎⁎⁎ | 0.146⁎⁎⁎ | |

| (0.020) | (0.036) | (0.017) | (0.038) | |

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| City FE | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Another low-carbon policy | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 6555 | 6555 | 5405 | 5405 |

| R2 | 0.856 | 0.856 | 0.813 | 0.813 |

(1) We used province-level clustering of robust standard errors and the wild clustering method proposed by Roodman et al. (2019) to eliminate clustering problems as much as possible. (2) Replace the explained variable. Regression tests were conducted by replacing end-of-year employment with the logarithm of the number of employees on duty. (3) Two methods were used in this study to screen the research sample data. The first was to regress the control variables after shrinking them by 1 % . The second was to shrink the control variables by 5 %. All of these tests were consistent with the baseline regression. Table 8 reports the regression results for other robustness tests.

Other robustness tests.

Under the constraints of the LCTPs, firms substitute the consumption of traditional energy sources such as coal with increasing green factor inputs, which increases the demand for labor as green factor inputs increase. In reference to relevant studies (Wu et al., 2025), we choose the logarithm of the sum of urban environmental governance investment and environmental protection financial expenditure as a measure of green factor input and evaluate whether the two pilot policies affect urban employment through green investment. Table 9 Column (1) reports that the estimated coefficients of the LCCP and CETP on green investment are 0.04 and 0.499, respectively, at the 1 % level of significance, indicating that the LCTPs contributed to an increase in green investment. Columns (2) and (3) are the coefficient estimates of green investment in urban employment, which are 0.046 and 0.056, respectively, at the 1 % level of significance, confirming that the LCTPs markedly increased the growth of green investment, thereby contributing to the improvement of urban employment. The increase in green factor inputs will, on the one hand, promote the development of new industries and create a large number of employment opportunities, for example, the expansion of solar panel production enterprises will increase a large number of employees, including production workers, technicians and so on. On the other hand, it will promote the green transformation and upgrading of traditional industries, which will increase the demand for personnel related to green jobs and drive the growth of employment; from the perspective of industrial linkage, the green transformation of traditional industries will lead to the development of upstream and downstream related industries, which in turn will create more jobs. The employment expansion mechanism of the green factor inputs of the LCTPs has been verified.

Mechanism for driving employment in green technology innovationTo verify the theoretical analysis segment of the green technology innovation mechanism, we gauged green technology innovation using the logarithm of the number of green patented technologies licensed. Table 10 Column (1) reports coefficient estimates of 0.299 and 0.685 for LCCP and CETP, respectively, at the 1 % significance level; Columns (2)- (3) present coefficient values for the influence of green technological innovation on employment, all of which are 0.070, at the 1 % significance level. This means that the two low-carbon pilot policies fostered urban employment by promoting green technological innovation. In order to gain a competitive advantage in the field of green industry, enterprises will increase their R&D efforts, which will attract more researchers, technicians and other high-skilled personnel to devote themselves to green innovation, leading to an increase in employment. Diffusion of technological innovation will produce knowledge spillover effect, other enterprises through learning and imitation of these green technologies, to enhance their own production technology level and innovation capacity. This knowledge spillover will lead to the upgrading of industries and economic prosperity in the whole city, further creating more employment opportunities. The employment-driving mechanism of the green technological innovation of low-carbon policies has been verified.

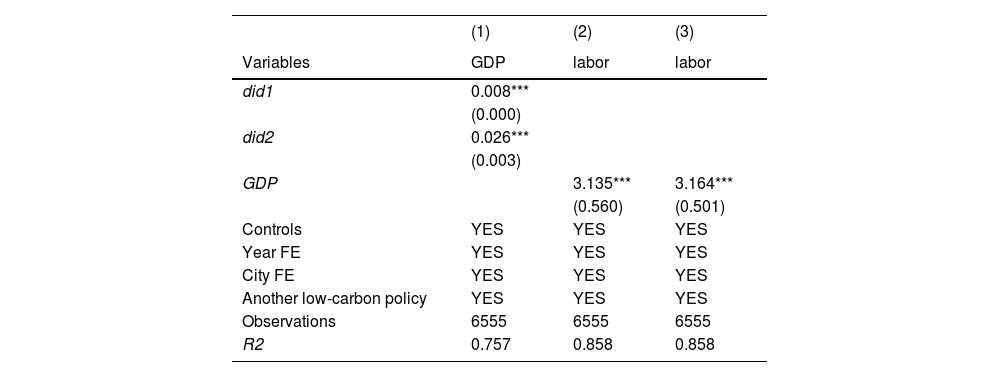

Mechanisms for job creation in the demand for green productsThe scale and cost effects generated by the increased demand for green products stemming from low-carbon pilot policies have varying impacts on employment; if the scale effect is greater than the cost effect, then employment increases, and, conversely, employment decreases. Therefore, we express output in terms of the logarithm of urban GDP. Table 11 Column (1) reports that the estimated coefficient values of the LCCP and CETP on output at the 1 % significance level are 0.008 and 0.026, respectively, and Columns (2) and (3) show that the coefficient values of output on employment at the 1 % significance level are 3.135 and 3.164, respectively. The regression results show that both the LCCP and the CETP promote employment through an increase in output. Satisfying consumers' green demand and expanding employment space. With the enhancement of consumers' awareness of environmental protection, the demand for green products and services is increasing, and the market scale of enterprises can be expanded to create more jobs; from the perspective of market demand pull, enterprises will continue to expand the types of green products and services to meet market demand, thus driving the synergistic development of the upstream and downstream industries, and creating more employment opportunities for the city. The employment creation mechanism of the green product demand of the LCTPs is verified.

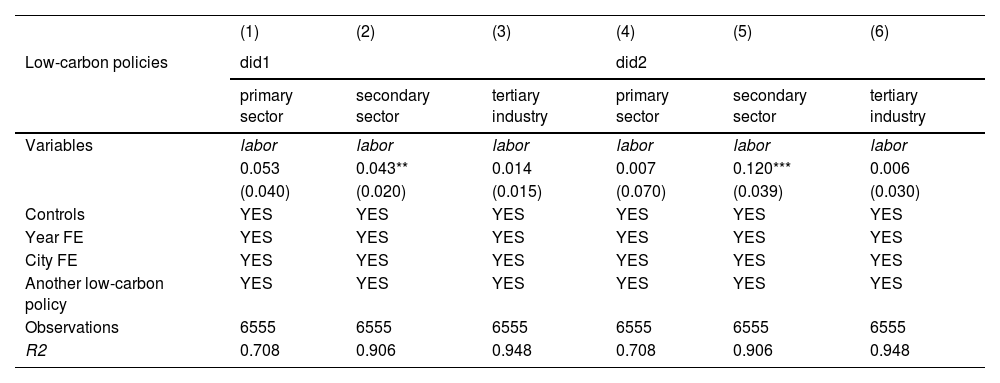

Heterogeneity analysis of the effect of the LCTPs on urban employmentDifferences across industries in citiesConsidering the varying carbon emissions of different industries, low-carbon policies might produce distinct results in terms of employment in the three major industries. Thus, this paper separately analyzes regressions for each of the three industries in the sample data, as shown in Table 12. The two LCTPs exert insignificant effects on employment in the primary and tertiary sectors but significantly more positive effects on employment in the secondary sector; the marginal effect of the CETP on the secondary industry is greater than that of the LCCP. It is likely that because China, as a global manufacturing power, has an absolute advantage in absorbing employment in the secondary industry but is also a major source of carbon emissions, the low-carbon transition has a more profound impact on the promotion of the green transformation of the secondary industry, driving the relevant enterprises to pursue green technological innovations, creating new jobs and leading to an increase in employment. The LCTPs have put more pressure on traditional enterprises to reduce emissions, forcing them to transition to green business, engage in green mergers and acquisitions, and develop green industries, with new industries leading to new employment. The LCCP can reduce carbon emissions effectively in the near term, but it also allows enterprises to bear more pressure; thus, driving employment is not as obvious as promoting the CETP.

Differences in the impact of employment in the various sectors.

Variation in China's location and resource endowment inevitably entails varying levels of employment impacts on the LCTPs. According to the location of the research sample, we refer to the division criteria of the Chinese Bureau of Statistics and classify the sample into three groups, namely, east, center, and west, and then conduct a grouping test. In Table 13, the LCCP positively increased employment in central and western cities, with greater marginal effects in central cities than in western cities and significantly negative effects in eastern cities. The CETP did not have a notable impact on employment in central cities but effectively increased employment in cities in the eastern and western regions, and the marginal effect on employment in western cities was greater than that in eastern cities; the impact of the CETP on employment was greater than that of the LCCP. The reasons for this may be as follows: first, the public in eastern cities is more aware of low-carbon and environmental protection, coupled with the relatively large size of the city itself, and the absorption capacity of employment is close to saturation, accompanied by the implementation of the LCTPs. Most cities will have high-emission industries because the transfer of the promotion of the employment effect is lower than that in the western region. Second, the western regions are rich in natural resources and have taken over some of the traditional industries, and because of the differences in national policies, the employment-led capacity of these regions has increased. Third, compared with the LCCP, the CETP can utilize the market mechanism to guide enterprises to strive for greater technological innovation and facilitate corporate green transformation, making the employment promotion effect of the CETP more obvious. Fourth, the two LCTPs have complementary impacts on employment in different areas, which together contribute to increased employment in cities.

Differences in employment impacts in cities of different regions.

Economic development differences lead to employment differences, as well as potential differences in the employment effects of the LCTPs in cities with varied levels of economic development. This paper measures economic development with GDP per capita; cities with GDP per capita greater than or equal to the median are regarded as developed cities, and the others are regarded as less developed cities. Then, regression is performed by grouping, and the results are shown in Table 14. The LCCP has an insignificant influence on employment in developed cities and a highly beneficial effect on employment in less developed cities. The CETP contributes positively to employment growth in all cities at the 1 % level, but the marginal effect on employment is greater in cities in developed regions than in less developed cities. Collectively, there are greater marginal impacts of the CETP on urban employment. A possible reason is that the LCCP has put enterprises under greater pressure to reduce emissions, and they had to reduce carbon emissions by reducing production or shutting down production, driving down the demand for enterprise labor. Under the CETP, through the market mechanism to regulate the environmental emissions of enterprises, enterprises can buy carbon emission rights for production in the short term. In the long term, in order to achieve sustainable development, enterprises are bound to realize green transformation through green technological innovation, especially in developed cities, where profitability and the willingness to engage in green transformation are greater. As a result, the production of enterprises will not be affected much, while green transformation causes the demand for personnel to increase simultaneously.

Differences in employment impacts in different cities.

City scale also affects the implementation effect of the LCTPs, which is consistent with the findings of relevant studies (Jiang et al., 2024). To categorize cities with resident populations greater than or equal to 5 million as megacities and cities with resident populations less than 5 million as large cities according to the size of the resident population of the cities in this paper, a grouping test is conducted. As shown in Table 15, first, Columns (1)- (2) and (3)- (4) show the impacts of the LCCP and the CETP on the employment of cities of different size classes, respectively. The coefficient estimates of the two LCTPs on the employment of megacities are positive but insignificant, and the coefficient estimates of the employment of large cities by either the LCCP or the CETP are positive at the 1 % level of significance, 0.106 for the former and 0.192 for the latter. Second, the average effect of the CETP on employment in large cities is approximately 8.6 % greater than that of the LCCP. The regression results show that the two LCTPs have had a more pronounced effect on increasing employment in large cities, possibly because megacities such as Shanghai, Guangzhou and some provincial capitals in East and Central China are basically close to saturation in terms of city size, and their absorptive capacity for employment is gradually diminishing. With the implementation of the LCTPs, these large and high-ranking cities have placed greater emphasis on low-carbon transformation than on economic growth targets, and the LCTPs have prompted such cities to relocate industries that have strong job-absorbing capacity but high energy consumption. Second, the implementation of a new national urbanization strategy has facilitated the coherent development of large, medium-sized and small cities, which greatly affects the cultivation of industries, population growth and increases in employment.

Differences in employment impacts in cities of different scale.

As a completely new factor of production, data are listed as one of the five basic factors of production, along with capital, labor, technology and land. Data elements have permeated all fields of the national economy, profoundly affecting and changing production, life and social governance (Kelley et al., 2024; Zhang, 2023). Therefore, can the combination of the LCTPs and data factors have a synergistic effect on employment and growth, and is it more effective in stabilizing employment and the economy? To explore how the combination of the LCTPs and data factors can produce a “synergistic” effect on “stabilizing employment” and “stabilizing growth”, according to the “Outline of Action for Promoting Big Data Development” issued by the State Council on August 31, 2015, the city corresponding to the province included in the national-level comprehensive big data pilot zone (NBPZs) is assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it is 0, and the test is conducted. As shown in Table 16, regardless of whether it is located in NBPZs, the LCCP significantly promotes urban employment at the 1 % level. Both the LCCP and the CETP have greater marginal employment effects in cities located in NBPZs. All these results show that the effective combination of data factors and the LCTPs generates an obvious synergistic effect on municipal employment, which can better contribute to increasing municipal employment.

“Stabilizing employment” effects of synergies between data elements and LCPP.

Taking the logarithm of urban GDP per capita as an explanatory variable, we verify the synergistic effect of the combination of data factors and low-carbon transition policies on economic growth. Table 17 reports the impact of the combination of data factors and the LCTPs on “stabilizing growth”, whether or not in NBPZs. The LCCP promotes economic growth at the 1 % level of significance, and the marginal effect of the LCCP on the growth of cities located in NBPZs is approximately 0.5 % greater than that of cities located in non-NBPZs. The growth effect of the CETP is significantly positive for cities in NBPZs and positive but not significant for cities in non-NBPZs. The above results show that the effective integration of data factors and the LCTPs has obvious synergistic effects on economic growth and that the organic combination of the two can better promote urban economic growth. Hence, it is essential to integrate data factors with the LCTPs to achieve high-quality development. Under the current downward pressure on economic growth, giving full play to the role of data factors is highly important for “stabilizing growth and employment”.

“Stabilizing growth” effects of synergies between data factor and LCPP.

This study examines China's low-carbon transition policies on urban employment using sample data from Chinese cities at the prefecture level and above from 2000 to 2022. We find that the two LCTPs have a proactive effect on stabilizing employment, but there are differences in that the marginal effect of the pilot policy on carbon emissions trading on urban employment is greater than that of the low-carbon city pilot by approximately 5 percentage points. The two LCTPs promote increased employment through the green factor input effect, the green technology creation effect and the green product demand effect. For different industries, both LCTPs significantly contributed to the increase in employment in the secondary sector, whereas there was no significant effect on the number of people employed in the primary and tertiary sectors. Across regions, the LCCP had a beneficial effect on employment in central and western cities, with a greater marginal effect in central cities than in western cities and a markedly dampening effect on employment in eastern cities. The CETP had a pronounced positive effect on employment in cities in the eastern and western regions, with a greater marginal effect on employment in cities in the western region and a negative but nonsignificant effect on employment in cities in the central region. The LCTPs have a nonsignificant influence on employment in developed cities and a highly beneficial effect on employment in less developed cities; the CETP contributes positively to employment growth in all cities at the 1 % level of significance, but the marginal effect on employment is greater in cities in developed regions than in less developed cities. With respect to cities of different sizes, the two LCTPs had a pronounced effect on promoting employment in large cities, whereas no effect was observed in megacities, with the marginal effect of the carbon trading pilot on employment being on average greater than that of the LCCP. The combination of data factors and the LCTPs had a more significant effect on “stabilizing growth” and “stabilizing employment”.

Based on the above findings, this paper draws the following conclusions:

In constructing a high-level socialist market economy, the market mechanism and administrative control are of vital importance, and both have different functions in the allocation of resources, complement each other and are indispensable. As far as the findings of this study are concerned, both the LCCP and the CETP stabilize employment, and the marginal effect of the CETP on urban employment is even greater. However, the market's fundamental role in the allocation of resources is to be brought into full play, and administrative means are a powerful complement to the market mechanism under different circumstances. The effects of the two LCTPs on employment have their own advantages and complement each other.

Second, both the LCCP and the CETP follow China's consistent “pilot first and then promote” approach to progressive reform. This model has proven to be suitable for China's development. This information is important for summarizing the experiences and problems of the LCTPs and avoiding the economic and employment pressures caused by wide-scale reforms. It can be selectively promoted on a pilot basis according to the effects of the two LCTPs in different circumstances.

Third, China's economy is currently facing multiple challenges, such as a complex and severe external environment and rising uncertainty, and multiple internal shocks, such as insufficient effective demand and greater downward pressure on the economy, “stabilizing growth”, and “stabilizing employment”, are the top priorities for achieving high-quality development. Research shows that the LCTPs stabilize employment through green factor inputs and green technological innovation and that technological innovation can improve output and realize scale effects; therefore, regions with these conditions should appropriately increase green investment and develop green industries, increase investment in R&D, emphasize technological innovation, optimize the innovation incentive system, and cultivate a favorable environment for innovation. We should stress the role of the market and give full play to the regulatory function of the government while promoting the green transformation of industries and green technological innovation so that the market and the government can organically combine to collaborate in promoting technological innovation and realizing green development.

Fourth, the secondary and tertiary sectors are increasingly contributing to the economy, but the secondary sector is also a dominant source of carbon and pollutant emissions. so LCPP should be brought into full play to promote the green transformation of the secondary industry, without affecting employment. Continuing to push forward the new urbanization strategy in depth, especially in the case that the scale and employment absorption capacity of special and mega cities are gradually becoming saturated, the new urbanization strategy has made a prominent contribution to fully utilize the large cities in accepting industrial transfers and improving their population absorption capacity and employment drive. Data factor has demonstrated its powerful kinetic energy in promoting economic growth, and it is of great significance to promote the effective combination of data elements and low-carbon transition policies to give full play to the fundamental role of data elements in economic growth and the important role of LCPP in low-carbon transition, and synergistically promote high-quality development.

Declaration Of interestsI have nothing to declare.

Funding sourcesFunding: This work was supported by the Autonomous Region Science and Technology Innovation Strategy Research Special Project (Grant No. 2024B04002–3), the Xinjiang University Outstanding Doctoral Student Innovation Project (Grant No. XJU2024BS020), the Xinjiang University Outstanding Doctoral Student Innovation Project (Grant No. XJU2024BS023), the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. 24EYB007).

CRediT authorship contribution statementYan Wu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Jinye Li: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. Xinfang Deng: Writing – original draft, Resources, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization.

None.

World Bank.(2012). Inclusive Green Growth: The Pathway to Sustainable Development. World Bank Publications.