It is essential to comprehend the feature and improvement path that supports the resilience of innovation networks under multiple crisis shocks. Studies have primarily examined the impact of network features on sustainable innovation outcomes yet overlooked the inter-organisational resilience feature of these networks. This study presents a measurement system to analyse resilience features in China’s new energy vehicle industry (NEVI) cooperative innovation network. To evaluate the evolution of network structures and functionality, this system integrates the static–dynamic framework, capturing static and dynamic impacts. The exponential random graph model is used to investigate the improvement path of innovation network resilience in the NEVI. Findings reveal that, from the perspective of static network resilience, the transportability of the innovation network decreases, while the level of aggregation remains high. From the perspective of dynamic network resilience, nodes with high transitivity and diffusion abilities significantly enhance the efficiency and scale stability of the NEVI’s innovation network. Improved network resilience is influenced by self-organisation, individual attribute, and exogenous network effects. This study enriches the literature on maintaining stability and sustainable development of innovation networks. It illustrates how to measure and improve the resilience of innovation networks to aid recovery from crises.

The innovation network plays a crucial role in addressing complex technical challenges, mitigating innovation risks, and leveraging external relationships for enterprises (Nonaka, 1998). Network research has focused on the investigation of individual characteristics within networks (Boxu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2019) and the impact of exogenous network attributes (Krichene et al., 2019; Liu & Prucha, 2018) on the causal relationship that influences innovation performance results. However, while most studies have focused on the positive results of the innovation network, few have explored the role of innovation networks in crisis situations. In fact, innovation is a high-risk process, affected by many uncertain factors (Gomes et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2022), which hinder the flow and diffusion of innovation elements across organisations. The increasing number of stakeholders makes the innovation network more vulnerable to uncertainties (Zhu et al., 2022). While China’s new energy vehicle industry (NEVI) has made significant progress, it also faces many internal and external challenges.

From the perspective of external risks, challenges such as policy shifts and unforeseen natural disasters can significantly undermine the stability of the knowledge creation network. For example, the ‘double-credit policy’ implemented in 2018 gradually reduced subsidies for new energy vehicles, directly affecting enterprises’ capital flow and market demand (Ou et al., 2018). Additionally, sudden natural disasters may also disrupt supply chains, interrupting production and delivery continuity (Park et al., 2013) and further hindering the coupled development of industrial ecological innovation networks (Liu et al., 2025). Therefore, the knowledge creation network needs to maintain its structural and functional stability and be able to respond quickly to changes, thereby enhancing network resilience.

From the perspective of internal risks, issues such as network embedding inertia, over-embedding, and improper embedding may weaken the innovation network (Granovetter, 1985). For example, excessive reliance on external partners and suppliers can lead to dependency on critical technologies and resources, resulting in technological stagnation and challenges in strategic adaptation when the network faces disruptions (Luo, 2003). The case of JAC Motors illustrates the importance of resilience in innovation networks. Initially focused on traditional fossil fuel vehicle manufacturing, JAC Motors transitioned to the new energy vehicle industry, achieving short-term stable returns through collaboration with NIO (Boxu et al., 2022). However, its entrenched business philosophy rooted in the fossil fuel market led to over-reliance on its external partner, Guoxuan High-tech, and a failure to achieve independent innovation in battery technology. This resource-integrated innovation model created a bottleneck in core technology development, constrained its innovation abilities, and impaired its market performance in a highly competitive environment. Consequently, in the current rapidly changing market environment, companies need to find more flexible and resilient innovation partners to avoid partnership lock-in, remain sensitive to changes in the internal and external environment (Sabatino, 2016; Conz & Magnani, 2020), and effectively mitigate internal risks within the knowledge creation network.

The diffusion of internal embedded risks and disruptions in external innovation resource flows significantly undermines the resilience of the knowledge creation network. These internal and external risks, viewed through the dual-risk perspective, necessitate robust static and dynamic resilience in the design of innovation networks. Static resilience mitigates risks such as internal innovation resource lock-in and the network’s vulnerability to the failure of core organisations (Nair & Howlett, 2016). Dynamic resilience enables adaptation to external environmental changes and unpredictable shocks, ensuring sustained technological innovation and market competitiveness (Kyrdoda et al., 2023). By enhancing static and dynamic resilience within the static–dynamic framework, the knowledge creation network can sustain innovation, adapt strategies, respond to external uncertainties, and provide a foundation for enterprises’ sustainable development (Iturrioz et al., 2015). Through examining the role of structural optimisation in the knowledge creation network, this study seeks to uncover how such adjustments can reinforce network resilience, enhancing its ability to adapt to evolving environments and withstand external shocks.

The structure of innovation networks serves as the primary lens for measuring resilience. Network structure directly affects the adaptability, flexibility and resilience of innovation networks, and is the key to dealing with external disruptions and internal risks (Kim et al., 2015).

First, structural characteristics shape the stability of cooperative relationships (Zeng, Xie, & Tam, 2010). In terms of robustness, characteristics such as network density and clustering coefficient determine the speed of risk diffusion (Gao et al., 2016). Sparse network structures characterised by low clustering demonstrate reduced risk transmission speed, yet they are particularly prone to collapse under targeted attacks. In contrast, dense and modular network structures offer multiple response pathways during external disruptions, reducing the negative impact of disruptions from a single partner (Skipper & Hanna, 2009) and improving the network’s absorptive ability.

Second, network structure governs resource mobility and collaboration efficiency. Well-structured innovation networks enable effective resource mobilisation and allocation, foster technology sharing, accelerate innovation, and bolster network resilience against disruptions (Tsai, 2001). As interactions within innovation networks are typically motivated by the pursuit of complementary heterogeneous resources, organisations prioritise connections with other organisations rich in innovation resources. Consequently, indicators such as node degree and centrality effectively measure enterprises’ embeddedness within the innovation network (Liu & Tang, 2020). Therefore, compared to top-down methodologies, a network structure–based bottom-up approach can more precisely reveal the underlying patterns of network resilience at the micro level from an integrated static–dynamic perspective. This highlights the critical role of the endogenous structure’s dynamic evolutionary process and its driving factors in shaping the resilience of innovation networks.

This study aims to develop a comprehensive measurement system for assessing resilience in the innovation network using complex network tools, grounded in the static–dynamic framework. The broader innovation ecosystem is examined, with a focus on China’s NEVI. By leveraging network dynamics, the analysis investigates how innovative organisations within China’s NEVI effectively maintain stability amidst ongoing disruptions. Furthermore, the driving mechanisms underlying the evolution of innovation network resilience are explored, with particular attention given to the key factors shaping this process.

This study makes several contributions to the fields of innovation network resilience and sustainable development, advancing our theoretical and practical understanding. First, it proposes a novel static–dynamic framework for assessing network resilience features in innovation networks, providing a comprehensive and nuanced perspective on how technological innovation systems respond to crises. Unlike studies that have primarily focused on network embeddedness (Andersen, 2013; Boxu et al., 2022), this research introduces a dual-risk perspective—integrating internal fragility and external shocks—to analyse structural persistence and functional adaptability. This approach enriches network resilience theory and offers a new analytical lens for evaluating the sustainability of industry-specific innovation networks.

This study makes theoretical and practical contributions to the fields of innovation network resilience and sustainable development. First, it introduces a static–dynamic framework, which integrates structural persistence and functional adaptability, offering a more comprehensive understanding of how innovation networks respond to crises from a dual-risk perspective. This framework extends resilience theory beyond traditional embeddedness-based analyses (Andersen, 2013; Boxu et al., 2022), providing an industry-tailored lens for assessing the sustainability of technological innovation systems. Second, it develops a theoretical model of network resilience tailored to the NEVI innovation network. Through stress test simulations and path analysis, it elucidates the mechanisms underpinning the stable operation of the NEVI’s innovation system. The findings demonstrate how static and dynamic resilience interact across different stages, providing empirical validation for theoretical models of network anti-interference capability (Jackson & Pernoud, 2020). Third, key generative mechanisms behind the formation of innovation network resilience are identified by exponential random graph models (ERGM), including the self-organisation, individual attribute, and exogenous network effects. The study demonstrates how different network structures facilitate knowledge integration and brokerage, confirming the insights of Powell et al. (1996) on alliance network evolution while extending them to the context of NEVI industries. Finally, from a practical perspective, this study offers actionable insights for improving innovation efficiency and fostering resilient collaboration within the NEVI innovation network. By identifying core nodes, optimising peripheral–core linkages, and leveraging geographical and organisational proximity, interventions can be designed to enhance resilience, which is essential for long-term industrial sustainability in a volatile global environment.

Literature reviewNetwork resilienceGiven the diverse and complex responses of different systems to disruptions, studies have proposed various definitions and evaluation methods for network resilience. Table 1 summarises research results on static and dynamic resilience in the innovation area. At its core, network resilience can be defined as a system’s ability to absorb, resist, and adapt to internal and external shocks or disturbances.

Research results on static and dynamic innovation network resilience.

| Authors | Static Resilience | Dynamic Resilience | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robustness | Absorptive ability | Transitivity ability | Diffusion ability | |

| Liu et al. (2024) | ✓ | |||

| Dovbischuk. (2022) | ✓ | |||

| Kammouh et al. (2020) | ✓ | |||

| Donnellan et al. (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Hossein et al. (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Francis and Bekera (2014) | ✓ | |||

| Wang et al. (2023) | ✓ | |||

| Liu and Song (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Dobson et al. (2019) | ✓ | |||

| Chen et al. (2022) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Lv et al. (2024) | ✓ | |||

| Elkhidir et al. (2023) | ✓ | |||

| Present study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Static resilience focuses on the ability of a system to maintain structural and functional stability under external shocks, emphasising the system’s resistance to interference. In areas such as transportation, urban infrastructure, and ecological networks, static resilience is used to evaluate the robustness and adaptability of systems (Zhang et al., 2015; Vivek & Conner, 2022; Jenelius, 2018). In innovation networks, static resilience reflects the stability of network structure and function against internal and external risks. It is usually evaluated using network topology indicators, including network density, clustering coefficient, and shortest path length (Liu et al., 2022). Research indicates that stable networks ensure the continuity of knowledge and sustain long-term inter-enterprise cooperation (Zhang et al., 2015; Bai et al., 2023). Robustness and absorptive capacity are the two main components of static resilience (Liu & Song, 2020). Robustness refers to the ability of an innovation network to preserve its core structure and function (Dovbischuk, 2022; Kammouh et al., 2020; Hosseini et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023; Dobson et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2022). Absorptive capacity highlights how the network mitigates the impact of external shocks through internal resources and cooperative mechanisms (Liu et al., 2024; Hosseini et al., 2016; Francis & Bekera, 2014; Liu & Song, 2020; Chen et al., 2022).

Dynamic innovation network resilienceDynamic resilience emphasises the ability to recover from shocks, focusing on structural and functional adjustments (Bhamra et al., 2011). It enables the network to swiftly reorganise and transform after disruptions. Through dynamic resilience, the innovation network can restore or even enhance its innovation abilities by reorganising partnerships, introducing new knowledge, and adjusting innovation strategies (Quax et al., 2013; Gonçalves & Ribeiro, 2020). Dynamic resilience is further categorised into transitivity and diffusion abilities (Donnellan et al., 2007). Transitivity ability refers to the ability of a network to quickly adjust its internal resource allocation to resume operations when it is disturbed (Elkhidir et al., 2023). Diffusion ability refers to the process of accelerating recovery and further enhancing innovation abilities through knowledge sharing and technology spillovers (Donnellan et al., 2007; Lv et al., 2024).

Influencing factors and evolution model of innovation network resilienceThe resilience of innovation networks is shaped by multiple factors, including network self-organisation, individual attribute, and exogenous network effects.

Network self-organisation effectThe network self-organisation effect refers to the process by which nodes in the innovation network form a global structure through spontaneous interaction. This effect significantly affects system resilience through structural redundancy, connection density and topological patterns. Centralised networks enable rapid crisis responses but are vulnerable to cascading risks from key node failures. In contrast, distributed networks show stronger robustness through redundant connections and resource-sharing mechanisms (Borgatti & Li, 2009).

Individual attribute effectsThe heterogeneous characteristics of nodes, including resource endowments, technological capabilities, and knowledge-sharing levels, profoundly shape collaborative patterns within the network (Brennecke & Rank, 2017). Nodes with superior attributes often serve as hubs for knowledge diffusion, with differences in technological potential driving the flow of innovation factors (Wang et al., 2024). In the NEVI, for example, leading enterprises such as Chery Automobile have established technology radiation networks through cross-patent licensing, while startups leverage manufacturing capabilities to embed themselves within the collaborative system. Such asymmetric cooperation accelerates technology diffusion but introduces risks of path dependence (Sun et al., 2018).

Exogenous network effectsExogenous network effects encompass the influence of external environmental factors, including policy changes, market demand fluctuations, and technological advancements, on the structure and behaviour of the network. These factors prompt nodes to adapt their strategies to address new challenges or opportunities (Shipilov & Gawer, 2020). In response to external pressures, innovation networks may use proactive strategies, such as cross-industry collaborations or strategic alliances to enhance network resilience (Ahuja, 2000). Alternatively, passive strategies may involve imitating competitors, securing external financial support, or adjusting product positioning to respond to crises (Deeds et al., 2000).

Evolution modelStudies have used gravity models, multivariate regression quadratic assignment procedures (MRQAP), and ERGM to analyse network evolution. Gravity models are limited by their focus on node degree centrality (Li et al., 2021), while the MRQAP method shows insufficiency in handling estimation bias caused by network dependencies (Dekker et al., 2007; Teng et al., 2021a). In comparison, the ERGM effectively captures the interplay of multiple driving mechanisms by modelling the joint probability distribution of network structure parameters (He et al., 2019). Based on the ERGM framework, this study dynamically analyses the evolution trajectory of China’s NEVI network by focusing on the synergistic effects of technological proximity and geographical agglomeration.

Research methodsNetwork structure and stage divisionDataThe vigorous development of the NEVI relies on sustained technological innovation, with invention patents serving as a direct indicator of innovation output. Given the cross-industry nature of NEVI-related patents, this study identifies relevant patents using International Patent Classification (IPC) codes, guided by the ‘Classification of Strategic Emerging Industries and Reference to International Patent Classification (2021)’ from the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA). It establishes a set of IPC codes, including B60L, B60K, H02J, H01M, and H02K, which encompass core NEVI technologies such as new-energy vehicles, electric vehicles, fuel cell vehicles, plug-in hybrid vehicles, and generators (Xiong & Zhang, 2022). These codes cover the upstream (e.g. lithium, nickel, platinum, rare earth materials, and other raw materials), midstream (e.g. batteries, accessories, motors, controls, and vehicle controls), and downstream (e.g. vehicle manufacturing, distribution, supporting services, and charging infrastructure) segments of the NEVI value chain (Liu, Hao, Cheng, & Zhao, 2018).

Data have been sourced from the PatSnap Global Patent Database, yielding 10,950 cooperative invention patents related to China’s NEVI. The data have been processed as follows: (1) Patents unrelated to NEVI have been excluded based on keywords, such as those involving ‘consumer electronics’, ‘industrial motors’, or ‘household appliances’; (2) To focus on geographical, spatial, and organisational proximity in subsequent analyses, patents involving individuals or organisations from Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan, or foreign organisations have been removed; (3) Each cooperative relationship among patent collaborators has been recorded once. After this screening, the study has identified 43,462 pairs of collaborative relationships among innovation actors, involving 5,565 enterprises, universities, and research institutes.

Stage divisionTo investigate the sustainable development characteristics of China’s NEVI innovation network, this study categorizes the network’s development into three stages: 2011–2014, 2015–2017, and 2018–2021. These stages are determined based on key policy issuances and industrial development status.

Fig. 1 illustrates the development of China’s NEV patent statistics. After being recognised as one of China’s strategic emerging industries in late 2010, the NEVI experienced notable growth. By 2015, China had become the global NEV market leader, surpassing the United States. In 2018, the industry transitioned from rapid growth to high-quality advancement amidst intensified competition. The years 2015 and 2018 marked critical milestones, with surges in patent applications and collaborative patent submissions.

A one-way ANOVA reveals significant differences in network average path length (F = 10.589, p = 0.006) and average clustering coefficient (Welch F = 14.733, p = 0.008) across the three stages. Post-hoc analyses using Tukey’s HSD and Games–Howell tests indicate that the average path length in stage 3 (2018–2021) is significantly longer than that in stage 1 (2011–2014) and stage 2 (2015–2017), reflecting a decline in network transportability over time. Additionally, the average clustering coefficients in stage 1 and stage 2 are significantly higher than in stage 3, suggesting a decline in network aggregation as the innovation network expanded.

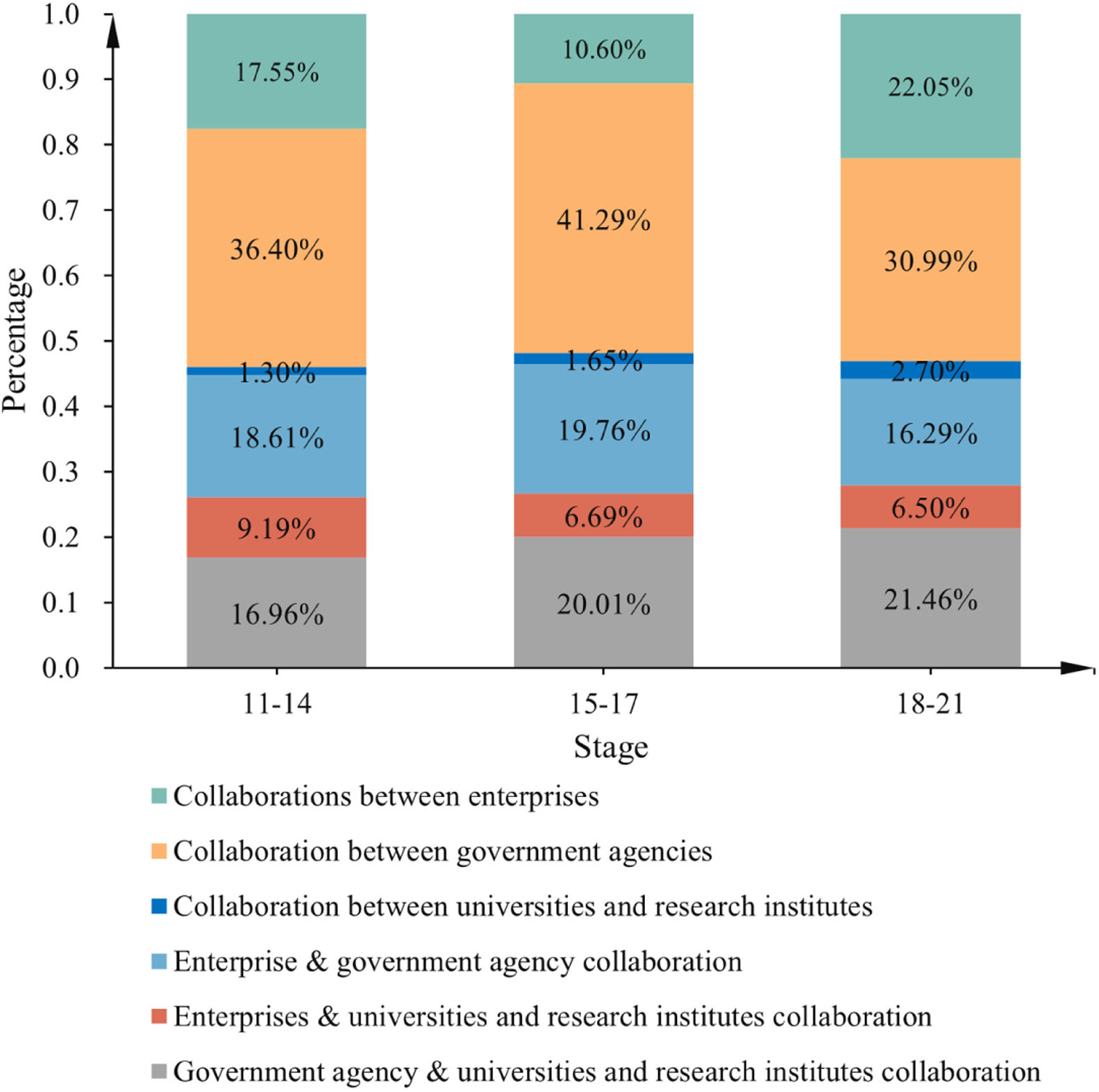

Data screening and processing have yielded 43,462 pairs of collaborative relationships among innovation organisations. The network of NEVI’s collaborative innovation organisations involves a total of 5,565 nodes, which includes 2,983 enterprises, 1,946 government agencies, and 636 universities and research institutes. As shown in Fig. 2, node heterogeneity is addressed by categorising organisations by type (enterprises, government agencies, universities, and research institutes) and analysing their connection distribution and roles within the network. Across the three stages (2011–2014, 2015–2017, and 2018–2021), enterprises account for approximately 50 % of the organisations in the network, with their proportion increasing progressively, indicating a strengthening of their dominant role in the network. Government agencies, comprising approximately 30 % of the total organisations, maintain a stable proportion across all three stages. Universities and research institutes, while experiencing a slight proportional decline over the stages, consistently represent more than 15 % of the network’s organisations.

Fig. 3 shows differences in NEVI innovation network structures over time. In 2011–2014, the network is small and loosely structured, with limited connectivity. In 2015–2017, the NEVI network forms a core–periphery structure centred around core nodes with strong relay and diffusion abilities. As the NEVI industry further develops, relying on node supplementation and chain-building measures, the network transitions from a sustained core–periphery configuration to an emerging periphery–multiple cores model in 2018–2021.

The scale of different types of innovation organisations and the proportion of collaborative innovation activities are calculated based on the classification results of various innovation organisations at different stages. As shown in Fig. 4, during the development of NEVI, enterprises have consistently maintained a leading role in innovation, reinforcing their dominant position in technological advancement. The random, implicit, and cumulative distribution of knowledge and technology resources within the network positions academic and research institutions as a critical structural hole. For instance, Tsinghua University acts as a structural hole by connecting the largest subnetwork of innovators with peripheral innovation groups centred around Chongqing Changan Automobile Co., Ltd. and Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co., Ltd. This connection facilitates the exchange of technology and knowledge between organisations that have significant gaps in their innovation capabilities, reducing the technology search costs for peripheral enterprises within the network.

Network resilience analysisThe resilience of innovation networks manifests itself through structural persistence and functional adaptability. The NEVI network’s resilience is quantified through a dual-dimensional analytical framework encompassing static structural attributes and dynamic evolutionary patterns. This approach addresses two critical dimensions: (1) inherent robustness derived from topological configuration and (2) adaptable ability emerging from node interaction dynamics. The evaluation system in Table 2 operationalises these theoretical constructs through six core indicators, each corresponding to specific resilience mechanisms.

Evaluation system of collaborative innovation network resilience.

Static network resilience reveals patterns of organisational cooperation and enables the evaluation of efficiency and dynamics in the allocation of innovative resources among network actors. It is assessed from two primary dimensions: robustness and absorptive ability. Robustness is evaluated using the average path length and slope of the degree distribution curve, which reflect the network’s ability to maintain structural stability under external shocks. Absorptive ability is measured by the average clustering coefficient, indicating how effectively the network leverages existing knowledge resources to mitigate the impact of external disruptions and minimise losses in innovation capabilities.

The average path length is a metric that quantifies the transportability of a network. When the average path length is reduced, network transmissibility increases, leading to a higher flow rate of innovative resources, among different organisations and higher transmission efficiency. The calculation of the average path length is shown in formula (1):

where i and j denote any two distinct nodes in the network; L represents the average path length; n is the total number of nodes in the network; and dij is the shortest path between nodes i and j.The slope of the degree distribution curve reflects the hierarchical structure of the network. A steeper hierarchy implies greater heterogeneity in the nodes’ ability to collaborate on innovation. For more details, refer to formulas (2) and (3)

where Ki is the degree of node i; C is the constant; Ki*is the degree ranking of node i; and α is the slope of the degree distribution curve.Network aggregation can be quantified using the average clustering coefficient. A higher value suggests stronger local interconnectivity and cooperative behaviour among neighbouring nodes, as indicated by formula (4)

where C represents the average clustering coefficient of the network; ki(ki-1)/2 is the theoretical maximum number of edges formed by node i in the network; and Ei is the number of connected edges actually formed by node i.Dynamic network resilienceThe objective of simulating dynamic network resilience measurement is to quantify the agglomeration that arises from multidimensional embedding. This process identifies nodes with the highest values in transitivity and diffusion ability as key nodes for embeddedness risk within the innovation network. The network stability index is used to evaluate the evolutionary changes in network structure and function when subjected to singular risk impact.

To assess the anti-interference measures of key nodes, simulations of dynamic network resilience in China’s NEVI innovation network used a combination of random node removal and targeted attack strategies. The positions and functional roles of innovation organisations vary due to differences in the number of link relations. Consequently, the failure of a key innovation organisation during simulation disrupts cooperative relationships with other critical nodes. This study evaluates anti-interference capability across two dimensions: transitivity and diffusion abilities.

Transitivity ability. The measurement of transitivity ability using three indicators: degree centrality, proximity centrality, and K-shell. Degree centrality quantifies an innovation organisation’s cohesion within the innovation network, as calculated in formula (5)

where ki represents the degree of node I, and N−1 is the maximum possible degree in the network. Nodes with high proximity centrality access optimal routes for resource acquisition, as computed in formula (6)where dij is the distance between nodes i and j. K-shell method is a coarse-grained decomposition technique that evaluates the significance of nodes by considering their network positions and the overall network structure. Smaller K-shell values indicate peripheral positions, while larger values denote the innermost network core.Diffusion ability. The assessment of diffusion ability employs two indicators: eigenvector centrality and PageRank. The eigenvector centrality of a node depends on the centralities of its neighbouring nodes. Thus, the significance of an innovative entity is determined by the importance of other organisations with cooperative relationships. The calculation formula for eigenvector centrality is presented in formula (7). PageRank is an iterative algorithm that models the movement of random walkers navigating through the graph by visiting nodes. When certain conditions are satisfied, the probabilities of visiting nodes converge to a steady distribution, and the stationary probability value of each node represents its PageRank value, as computed in formula (8):

where A represents the adjacency matrix of the innovation network; λsignifies the corresponding eigenvalue of the adjacency matrix; CPR(ui)i−1 denotes the PageRank value of each node that can link to vi; andCL(ui) represents the number of outgoing links for each node.Stability indices. External attacks affect the realisation of the innovation network functions by altering its structure, destabilising the network. The network stability index quantifies structural changes induced by risk factors, with network efficiency and effective scale as key indicators. Dynamic changes in network efficiency and effective scale reflect the rate of degradation in the innovation network’s structure and function under risk exposure. Specifically, these indicators measure the duration required for the network to collapse or fail under continuous risk exposure. Network efficiency E quantifies the rate of information flow and the cost of resource transmission within the innovation network. Shorter distances between nodes indicate faster information flow, lower costs, and enhanced network stability, as calculated in formula (9). Effective scale S represents the ratio of the maximum connected subgraph’s size to the overall network size, as computed in formula (10):

where dij represents the distance between node i and node j.Perturbation modes and interrupt rules. The innovation network faces external disturbances through two primary strategies: stochastic and deterministic. The stochastic strategy involves randomly removing a designated percentage of nodes to render them non-functional. In contrast, the deterministic strategy targets nodes based on their anti-interference index. In simulations, both strategies apply a node failure rate of 1/15 per time period, with disturbances ceasing once all nodes have failed. The perturbation process is implemented using the NetworkX package in Python, adhering to the specified interrupt rules.

Influencing factors of network resilienceThis study constructs an ERGM to investigate the driving mechanisms of network resilience in the NEVI innovation network, as specified in formula (11):

The probability of connection between different nodes is the explained variable, where Y represents the connection between two different nodes: Y=1 when they are connected and Y=0 otherwise (Robins et al., 2007). Using Markov chain Monte Carlo maximum likelihood estimation (MCMC-MLE), the model determines optimal estimation parameters to assess the impact of variables on the probability of node cooperation. Model goodness of fit is evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), with smaller values indicating superior fit.

The explanatory variables comprise network self-organisation effect, individual attribute effect, and three exogenous network effect variables (Teng et al., 2021a). Table 3 presents the selection of these explanatory variables for ERGM. When analysing the network self-organisation effect, Bonferroni correction is applied to compare results across the three developmental stages due to stage-wise differences in how various network structures influence resilience. This adjustment controls for Type I error inflation caused by multiple comparisons. Bonferroni correction is a method that enhances the robustness of statistical inference by adjusting the significance level, effectively reducing the probability of false positives arising from multiple hypothesis tests (Forstmeier et al., 2017). In contrast, the discussions on individual attribute and exogenous network effects focus more on their direct impacts on network resilience functionality. Individual attributes, although changing over time, do not involve cross-stage comparisons in this study, while exogenous network attributes are relatively fixed in nature. Therefore, these effects exhibit consistent patterns across all three stages, making it unnecessary to apply Bonferroni correction for inter-stage difference analysis.

Network self-organisation effectTo capture the network self-organisation effect and enhance the ERGM’s goodness of fit, this study selects edges, geometrically weighted degree distribution (GWDeg), geometrically weighted edgewise shared partners (GWESP), and geometrically weighted dyad-wise shared partners (GWDSP) as variables. GWESP represents the triangular closure structure formed by innovation organisations, indicating enhanced node cooperation and efficient transfer of innovation resources within the triangle. GWDSP characterises the open triangle structure and the bridging role of intermediary nodes. The way in which network configurations among innovation organisations influence the development of cooperative innovation relationships within the network is examined by incorporating these network self-organisation effect variables.

Individual attribute effectTo assess the impact of individual attributes on cooperation among innovation organisations, this study identifies experience and activeness as key metrics. Individual experience is measured by the duration of an organisation’s presence in the network, while activeness is quantified by the total number of patents the organisation participated in from 2011 to 2021. Early network entry signifies higher experience, indicating a more prominent role. This prominence fosters a preferential connection mechanism, increasing cooperation likelihood and exemplifying the Matthew effect in the network.

Exogenous network effectThis study selects geographical, spatial, and organisational proximity as exogenous network effect variables to identify characteristics that make certain organisations more attractive for collaboration. A preference for cooperation with nearby innovation organisations indicates reliance on geographical proximity for technological collaboration. Similarly, collaboration with organisations in neighbouring cities highlights the role of spatial proximity. Additionally, a tendency to partner with organisations of the same type suggests dependence on organisational proximity. Geographical distance is calculated as the centroid distance between prefecture-level cities. Spatial proximity is assigned a value of 1 for organisations in adjacent prefecture-level cities and 0 otherwise. Organisational proximity is assigned a value of 1 for cooperative relationships between innovation organisations of the same type and 0 otherwise.

Empirical resultsStatic resilience featureTable 4 presents the fundamental characteristics and static resilience feature indices of China’s NEVI innovation network. In stage 1, the network comprises only 537 organisations, forming 565 cooperative relationships and 2,201 connections. In stage 2, the network expands to 1,311 organisations, with 1,712 relationships and 9,193 connections. In stage 3, the network grows significantly to 3,717 organisations, 4,941 cooperative relationships, and 32,068 connections. Across these stages, newly established connections among innovation organisations consistently outnumbers dissolved relationships, indicating sustained network expansion and increasingly robust cooperation among nodes. The average degree increases from 2.10 in stage 1 to 2.61 in stage 2 and 2.66 in stage 3, reflecting a rise in the average number of partners per node and enhanced cooperation within the network. However, network density decreases from 0.004 to 0.001, suggesting sparser connections. This sparsity likely results from the disproportionate growth in the number of innovation organisations relative to their collaborative ties, indicating significant potential for further network expansion.

RobustnessThe average path length shows an increasing trend and increases significantly in the transition from stage 2 to stage 3. This trend indicates that as the innovation network’s scale grows, connectivity diminishes, reducing the efficiency of information and resource transmission and weakening the network’s overall robustness. The influx of numerous innovation organisations introduces instability, limiting the accessibility of certain nodes within the cooperation network. Additionally, as shown in Table 4, the absolute slope of the degree distribution trends upward, signalling a strengthening network hierarchy and increasing heterogeneity. This results in a pronounced distinction between dominant core and peripheral nodes, reinforcing the prominence of core organisations, amplifying the Matthew effect, and highlighting uneven innovation development and varying innovation capacities among nodes. From the perspective of robustness, while the strengthened core–periphery structure enhances the stability of core nodes, it increases the innovation network’s dependence on these nodes, potentially reducing resilience to targeted disruptions.

Absorptive abilityAs shown in Fig. 5, the average clustering coefficient across the three stages of the NEVI innovation network exhibits a slight decline but remains high. This shows that the network has a high degree of aggregation, close connections between nodes, and a low degree of cooperative isolation. A high clustering coefficient reflects stable cooperative relationships among innovation organisations, facilitating knowledge sharing and flow, thereby enhancing the innovation network’s absorptive ability. Furthermore, close collaboration fosters mutual trust, reduces opportunistic behaviour, and strengthens the network’s adaptability to external disruptions. The highly clustered structure ensures that when certain nodes face external shocks, neighbouring innovation organisations provide support through interconnected cooperative networks, maintaining the continuity of innovation activities. Consequently, the elevated average clustering coefficient bolsters the network’s absorptive ability.

Dynamic resilience featureInfluence of anti-interference measuresFig. 6 shows the efficiency changes within the network over the sample period (2011–2020), using five key node identification methods. Network efficiency measures the speed and cost of circulating network resources within the global network. The five intentional attack methods illustrate the significant impact of key node destruction in the network aggregation process. During the initial stage, disruptions reduce network efficiency. Notably, transitivity ability indicators reveal that removing nodes with high centrality values severely impairs network efficiency, while diffusion ability indicators show that targeting nodes with high PageRank values causes the fastest decline. Network efficiency approaches zero when the top 6 % of nodes are removed. Intentional attacks based on high eigenvector centrality and proximity centrality reduce efficiency to near zero after the top 20 % of nodes are removed.

Fig. 7 illustrates variations in the effective scale of the NEVI innovation network from 2011 to 2020. The effective scale represents the flow of information resources within the largest connected subgraph. Similar to network efficiency in Fig. 5, the effective scale declines during initial disruptions. Removing the top 6 % of highly centralised nodes or those with high PageRank values weakens intentional attack strategies, leading to near-complete network structure breakdown. However, attacks targeting nodes with high transitivity ability do not cause complete collapse in the initial stage, with the network retaining approximately 10 % of its size. In contrast, attacks based on high diffusion ability have a lesser impact, with the effective scale reaching zero only after 60 % of nodes are removed.

Fig. 8 illustrates the influence of node anti-interference on the efficiency of the NEVI innovation network across three stages. From 2011 to 2014, the network’s limited scale leads to an immediate drop in efficiency to zero following attacks. From 2015 to 2017, the network demonstrates a retention of approximately 50 % efficiency despite encountering random attacks on 25 % of its nodes. However, intentional attacks on 25 % of the nodes still exhibit a significant impact, indicating that the network has a certain level of resilience against random risks. From 2018 to 2021, network efficiency generally declines under random attacks but occasionally increases, reflecting improved local adaptation to exogenous shocks. Despite the intentional attack strategy, the network efficiency declines persistently, while the impact of different attack strategies on the network remains predominantly unchanged.

Fig. 9 illustrates the impact of node anti-interference on the efficiency of the NEVI innovation network across stages. The effect on effective scale aligns with the effect on efficiency. Intentional attacks targeting nodes with high transitivity and diffusion abilities, particularly those with high centrality and PageRank values, exert a more destructive influence on the effective scale during 2015–2017 and 2018–2021 compared to other strategies, consistent with Fig. 7.

Analysis of random attack trends in Figs. 8 and Fig. 9 reveals a fluctuating pattern, with temporary enhancements occurring within a broader pattern of decline. From 2011 to 2014, the innovation network’s single–core structure leads to immediate disruptions under attacks. From 2015 to 2017, during the industry’s transition from incubation to growth, the average and maximum degree increases significantly. New innovation organisations heavily rely on core nodes, limiting independent innovation and resulting in low adaptation to exogenous risks in terms of network efficiency. From 2018 to 2021, the number of network subgraphs doubles, while the average clustering coefficient exhibits a decrease. Furthermore, innovation organisations have started to transition from the conventional ‘local search’ thinking logic, leading to a wider range of cooperative relationships among these organisations. These changes have contributed to the enhancement of local adaption in terms of network effectiveness. The emergence of a multi-core structure increases innovation opportunities, enabling the effective scale to exhibit strong resilience against random attacks.

Performance of different anti-interference levels of nodesDynamic analysis of the NEVI innovation network indicates that nodes with a high degree centrality and high PageRank have a significant influence on the efficiency and effective scale of the network. Fig. 10 ranks the top–10 innovation organisations based on transitivity and diffusion abilities across three stages.

From the perspective of core nodes of the innovation network, analysis of Figs. 3 and Fig. 10 indicates that the innovation network exhibits a first-order dominant structure with a pronounced polarisation effect, consistently positioning the State Grid Corporation of China as the top-ranked node. During the first two stages, approximately 20 % of nodes establish cooperative relationships with the State Grid Corporation of China, which actively leads enterprises, universities and research institutes to drive the rapid development of the NEVI innovation network. Leveraging its transitivity ability advantage, the State Grid Corporation facilitates technical exchanges and interactions among diverse innovation organisations, extending the innovation chain and promoting network expansion. Consequently, its disruption significantly impairs network efficiency and architecture, underscoring its critical role in sustaining network resilience.

From the perspective of the continuous evolution of the innovation network, the collaborative innovation among industry, academia, and research (IAR) significantly bolsters the enhancement of innovation resilience. The composition of innovation organisations has shifted from a simpler academic–research model to a complex IAR networked model. Research institutes, such as the China Electric Power Research Institute, leverage robust research capabilities and experience to maintain pivotal roles, though their centrality dynamically shifts over time. Leading universities, including Tsinghua University and Southeast University, use their talent pools and research expertise to foster close collaborations, particularly in stage 3, in which nine universities ranked among the top-20 nodes, solidifying their influence as integral network pillars. Enterprises such as Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co., Ltd. and Nanrui Group Co., Ltd., collaborate with research institutes and universities to integrate complementary resources, facilitating the circulation of advanced technologies across innovation organisations.

Improvement paths of network resilienceTable 5 demonstrates that different network configurations have varying effects on the generation of node cooperation at different stages of the NEVI innovation network’s development.

Parameter estimation of the driving factors of resilience of innovation network.

Note: The statistical significance levels for ***, **, and * are 0.1 %, 1 %, and 5 %, respectively, with standard error values in parentheses.

The GWDeg network configuration is significant with a p-value of 0.1 % in stage 1 and 1 % in stage 2, but is not significant in stage 3. Further Bonferroni-corrected comparisons shown in Table 6 reveal statistically significant differences between all three stages, indicating that the cooperation relationships among innovation organisations became increasingly complex as more nodes were added to the network. This evolution suggests a shift from simpler, centralised structures to more diversified configurations, in which multiple nodes play pivotal roles in shaping the network’s topology. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of the network self-organisation effect, particularly during its early and middle development phases. For example, during stage 1, the Power Science Research Institute of Guangdong Power Grid Co., Ltd., establishes a GWDeg network configuration consisting of only four nodes, including Chongqing University. In stage 3, it expands to include many GWDeg structures involving the Guangdong Power Grid Co., Ltd., dispatching control centre, NR Engineering Co., Ltd., and the University of Hong Kong (Shenzhen Institute of Research and Innovation).

Bonferroni-corrected for the network self-organisation effect coefficients.

Note: The coefficient differences across time periods are calculated using Wald tests. Significance levels are adjusted using the Bonferroni correction (αadjusted=0.05/3≈0.0167). Coefficient differences and standard errors are based on Table 5.

The GWESP network configuration is significant with a p-value of 0.1 % across all three stages. Moreover, Bonferroni-corrected results show that the coefficient difference between 2011–2014 and 2018–2021 is statistically significant, suggesting that the propensity for forming closed triangles has strengthened over time. This finding suggests that nodes within the network exhibit a tendency to form a patent cooperation structure characterised by triplet closure. This structure enables the transfer of innovation resources within the triangle, resulting in knowledge integration, increased mutual trust between nodes, and decreased risk and uncertainty in cooperation. Stage 1 features GWESP structures such as the State Grid Corporation of China, XJ Group Corporation and State Grid Beijing Electric Power Company. Stage 2 features GWESP structures such as Tsinghua University, North China Grid Co., Ltd., and China Electric Power Research Institute. Stage 3 features GWESP structures such as Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co., Ltd., Shanxi New Energy Vehicle Industry Co., Ltd., and Zhejiang Geely New Energy Commercial Vehicle Group Co., Ltd.

The GWDSP network configuration is not significant in the first stage but is significant at the 0.1 % level in stages 2 and 3. However, Bonferroni-corrected tests indicate no significant differences between any pair of stages. This result suggests that despite a general trend toward the adoption of open triangular structures—where intermediary nodes act as bridges connecting disparate parts of the network—changes across developmental phases are not statistically distinguishable. Therefore, the observed increase in GWDSP values may reflect a gradual, rather than abrupt, transformation in the network’s ability to mediate innovation flows through brokerage mechanisms. This highlights the need for further investigation into the contextual factors driving the emergence and stabilisation of such intermediary roles over time. In stage 2, multiple GWESP structures are present, including Shanghai Zhongju Jiahua Battery Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai Jiaotong University, Zhoushan Jinqiu Machinery Co., Ltd., Hainan Guangyu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai Jiaotong University, and Shanghai Automotive Group Co., Ltd. Shanghai Jiaotong University functions as an intermediary bridge within this network.

These findings highlight the role that evolving network configurations play in creating intricate structures among innovation organisations, enhancing the innovation network’s ability to withstand and adapt to disruptions, thus promoting sustainable development. Organisations with strong transitivity and diffusion abilities form central and intermediary structures, positioning them at the network’s core, controlling innovation resources, and demonstrating high network resilience.

Individual attribute effectTable 5 shows significantly positive coefficients for individual experience and activeness with a p-value of 0.1 % across all three stages, indicating their critical role in fostering cooperative relationships. Innovation organisations exhibit a preferential attachment mechanism, favouring collaboration with nodes possessing greater experience and higher activeness. This reinforces the core status of advantaged nodes, exemplifying the Matthew effect. Early entrants to the innovation network accumulate significant experience, build strong reputations, establish extensive connections, and readily collaborate with others. Similarly, higher patent activity from 2011 to 2021 signals greater innovativeness and attractiveness. Interactions within the innovation network prioritise acquiring complementary heterogeneous resources, leading innovation organisations to form relationships with resource-rich nodes that have priority access. This contributes to degree–value clustering, explaining why nodes such as the State Grid Corporation of China and China Electric Power Research Institute consistently demonstrate strong transitivity and diffusion abilities, enhancing network resilience.

Exogenous network effectTable 5 also reveals that cooperative relationships depend on geographical, spatial, and organisational proximity. Geographical proximity is positively significant at the 1 % level in stage 1 and remains positively significant at the 0.1 % level in stages 2 and 3. Innovation organisations tend to collaborate with geographically proximate partners, enabling rapid knowledge and technology exchange, reducing communication costs, mitigating risks from information asymmetry (Giuliani, 2013), and enhancing innovation output. This proximity ensures swift resource flow, bolstering network resilience against external disruptions.

Spatial proximity impact varies across stages. In stage 1, it positively influences collaboration, but in stages 2 and 3, its effect becomes negative. Advances in technology and transportation have reduced regional barriers, promoted seamless communication, and enhanced the mobility of innovation cooperation, thereby diminishing reliance on neighbouring cities.

Organisational proximity is statistically significant at the 0.1 % level across all stages, with positive coefficients. Innovation organisations prefer same-type partners, with cooperation probabilities 1.08-fold, 4.25-fold, and 4.67-fold higher for same-type pairs in stages 1, 2, and 3, respectively. Similar organisational structures and incentives foster trust and reduce communication barriers, enabling efficient and cost-effective collaboration, which enhances cooperation likelihood and network resilience.

Comparison of three types of effectsComparing models 1, 2, and 3 reveals that incorporating exogenous network effect variables in Model 2 significantly reduces the AIC and BIC, indicating improved goodness of fit. Adding network self-organisation effect variables in model 3 further enhances fit, suggesting that exogenous network effects exert a stronger influence on node cooperation than self-organisation effects. These findings underscore the critical role of proximity in driving network resilience within the NEVI innovation network.

Conclusion and discussionMain conclusionsFrom a static perspective, rapid industrial development has driven continuous expansion of the NEVI innovation network’s scale and an increase in the number of innovation organisations. However, network transmissibility has gradually declined, indicating challenges to network robustness. Nevertheless, high network aggregation strengthens cooperation among adjacent innovation organisations, thereby enhancing the innovation network’s absorptive ability. The increasing network hierarchy introduces greater heterogeneity, offering diverse cooperation opportunities to innovation organisations. Despite these advancements, the NEVI innovation network retains significant development potential. Future efforts can enhance robustness and absorptive ability by optimising network structure, improving connectivity, and balancing cooperation, thereby bolstering static network resilience.

From a dynamic perspective, the NEVI innovation network’s evolution facilitates knowledge and technology flow, with core nodes playing pivotal roles in transitivity and diffusion processes. However, as the scale of the network expands, the hierarchical structure complicates information transmission, limiting peripheral innovation organisations’ connectivity and reducing overall transitivity ability. Although some high-centrality nodes have promoted the rapid diffusion of technology, the flow of innovation resources in the network is still unbalanced, limiting the breadth and depth of knowledge sharing. To address these challenges, strengthening connections between peripheral and core nodes, optimising information transmission paths, and enhancing network redundancy can improve transitivity and diffusion abilities, thereby reinforcing dynamic network resilience.

From the perspective of an improvement path, the network resilience of the NEVI innovation network has evolved from core-driven resource aggregation to closed collaboration and intermediary diffusion. In the early stage, core nodes such as the State Grid Corporation of China leveraged GWDeg structures to enhance robustness. Subsequently, widespread GWESP structures fostered ternary closed cooperation, improving knowledge integration and collaborative innovation. As the network further developed, the GWDSP structure became prominent, with intermediary nodes enhancing knowledge transfer and diffusion, bolstering adaptability to external shocks. Simultaneously, the individual attribute effect shows that experienced and active innovation organisations are preferred collaboration partners, reflecting the Matthew effect. The exogenous network effect shows that the impact of geographical proximity on innovation cooperation weakens over time, while organisational similarity consistently stabilises cooperative relationships. Overall, network resilience depends on a dynamic optimisation process from resource aggregation to collaborative innovation and efficient diffusion.

Theoretical significanceThis study advances the literature on innovation network resilience and sustainable development through three distinctive theoretical contributions, particularly in the context of crisis response.

First, a static–dynamic framework is proposed to assess innovation network resilience, integrating structural persistence and functional adaptability. Unlike studies that focus on network embeddedness (Andersen, 2013; Boxu et al., 2022), this study employs a dual-risk perspective, considering internal fragility and external shocks, to analyse these dimensions. By differentiating static resilience (encompassing robustness and absorptive capacity) from dynamic resilience (involving transitivity and diffusion ability), the study offers a more nuanced understanding of how innovation networks sustain stability and recover from disruptions. This dual-risk lens enriches network resilience theory (Hong et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024), offering a comprehensive approach to evaluating crisis response in technological innovation networks.

Second, this study extends the conceptualisation of network resilience mechanisms by identifying key structural factors influencing innovation sustainability. It demonstrates that high clustering and modular structures enhance network robustness, facilitating stable knowledge exchange and cooperation among innovation organisations, including enterprises, universities, and government agencies. Conversely, reduced absorptive ability indicates bottlenecks in resource flow, particularly during external shocks such as policy shifts or supply chain disruptions. Dynamically, core nodes with high centrality and PageRank values play critical roles in sustaining network efficiency and scale during recovery, as evidenced by stress test simulations. These findings empirically validate theoretical models of network anti-interference capability (Jackson & Pernoud, 2020) and align with discussions on systemic risk and adaptive capacity in complex systems (Gao et al., 2016).

Third, this study uncovers generative mechanisms driving network resilience formation. The results show that innovation networks evolve through GWESP and GWDSP structures, reinforcing the insights of Powell et al. (1996) on alliance network evolution while extending them to high-tech contexts. Organisational proximity and prior experience significantly shape collaboration preferences, confirming the role of relational embeddedness in sustaining network resilience. This study complements Liu et al. (2024)’s provincial-level analysis of innovation network resilience by elucidating enterprise-level network structures’ impact on resilience dynamics. While Liu et al. (2024) highlight the dominant role of market entities, our findings offer granular insights into enterprise-level cooperation patterns, clarifying how these entities enhance regional network resilience. This advances their framework by revealing micro-level mechanisms for resilience improvement.

Managerial implicationsGovernments should implement a dual-focused strategy for policymakers to bolster the network resilience of NEVI’s innovation networks. First, policymakers should enhance structural awareness by systematically analysing innovation network dynamics to identify and strengthen key nodes that facilitate robust knowledge exchange. By providing targeted incentives, governments can promote the strategic integration of different organisations, optimising local clustering and cross-regional connectivity. This approach requires dismantling administrative barriers to ensure seamless knowledge flows while preserving specialised innovation clusters where geographic proximity enhances collaboration. Second, governments should prioritise the strategic development of core organisations. Policymakers should empower organisations with high transitivity and diffusion abilities to facilitate knowledge transfer across network segments, enabling less advanced participants to access critical technologies. This balanced strategy of strengthening dense clusters while fostering strategic bridges enhances innovation network resilience to withstand disruptions and sustain dynamic adaptability.

Managers should adopt a dual-strategy approach that balances strong and weak ties, thereby strengthening static robustness and dynamic adaptability. Long-term strategic partnerships foster deep knowledge integration, while external connections, such as those established through academic conferences or open-innovation platforms, promote flexibility. Managers should prioritise partnerships with highly active innovators to ensure reliable and stable knowledge exchange. Additionally, innovation managers should actively identify and participate in self-organised collaboration structures, particularly triadic relationships involving enterprises, government agencies, universities, and research institutes. These GWESP-based structures significantly enhance network resilience by promoting knowledge co-evolution and reducing uncertainty in innovation processes. By forming stable triads, enterprises can improve internal coordination and bolster the innovation network’s capacity to absorb and respond to external shocks. To sustain these collaborative models, managers should seek institutional support from government agencies or industry associations, which can establish structured frameworks for long-term cooperation and co-innovation.

Limitations and future workDespite its theoretical and practical contributions, this study has certain limitations. First, while patent collaborations provide quantifiable metrics for formal knowledge exchange, they may not capture informal cooperation, tacit knowledge sharing, or intangible inter-organisational relationships that contribute to innovation. Future research could incorporate textual data to better assess these aspects and enhance network resilience evaluation.

Additionally, the ERGM model operates under the Markovian network evolution assumption, which posits innovation networks as continuously updating processes. However, this assumption proves unrealistic when examining the evolutionary trajectory of NEV innovation networks. In reality, the NEV market has experienced intensified competition due to subsidy reductions and market entry by foreign competitors such as Tesla. This competitive landscape necessitates deeper investigation into how endogenous (internal organisational dynamics) and exogenous factors (external market forces) collectively shape innovation organisations’ embedding behaviour and network structural evolution. Future studies could explore the impact of external factors, such as subsidies, on the NEVI innovation network’s sustainable development by analysing entry and exit dynamics of innovation organisations. Beyond patents, alternative indicators such as research publications, technology contracts, and talent exchanges could measure technological knowledge flow. Establishing a comprehensive innovation network system that integrates these metrics would provide a holistic evaluation of sustainable innovation cooperation by the NEVI.

Funding sourceThis study was supported by grants National Social Science Fund of China (21BGL304).

CRediT authorship contribution statementLongfei Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Junnan Zhang: Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Chao Liu: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Yuyue Guan: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Methodology, Data curation. Wan Kang: Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The authors thank Yuanqing Nie for her insightful comments and discussions, and Keyi Lu for her contributions to the literature review.