Digitization has reshaped corporate innovation. However, few studies have explored how companies can fully incentivize their human capital in the digital transformation process to improve innovation capabilities. To address this gap, this study proposes a configurational framework that incorporates the degree of digitization and five key incentive mechanisms—namely, executive compensation incentives, executive equity incentives, employee compensation incentives, employee stock ownership plans, and pay gaps. Based on dynamic qualitative comparative analysis and regression analysis, this study utilized balanced data of 1387 listed manufacturing companies in China from 2016 to 2023 to explore the complex causal mechanisms driving high corporate innovation efficiency (IE). We found that no single factor constitutes a necessary condition for high corporate IE, but the necessity of executive and employee compensation incentives increased over time. Moreover, seven configuration paths leading to high corporate innovation efficiency were identified and integrated into four strategic solutions that vary across temporal dimensions, company size, and marginal effects. Our study demonstrates that the key to improving IE in the digital age lies in managing the relationship between digital value creation and human capital value distribution. The results provide important theoretical and practical insights into promoting high-quality innovation development in companies.

Innovation is essential for sustaining a company’s long-term competitive advantage. Digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), big data, cloud computing, and 5 G, are transforming global industries. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2020) states that digital technologies are the primary drivers of innovation for companies and that digitization is reshaping business innovation. Several studies indicate that digital transformation (DT) positively impacts corporate innovation (Gaglio et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2022). In manufacturing, DT further enables green, low-carbon, and sustainable development (Chen et al., 2023; Singh et al., 2025). Manufacturing in China is a central pillar supporting the national economy, and upgrading its value chains has been a major focus of national industrial policy. The government has issued a series of policies to promote DT (Peng & Tao, 2022; Wang et al., 2025). The 14th Five-Year Plan states that new-type industrialization should essentially be achieved by 2035 (The State Council of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). Driven by technological revolutions and industrial policies, DT has become a strategic consensus in manufacturing to promote innovation and sustainable development (Feng et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2023). Numerous companies have begun pursuing DT and achieved breakthroughs in the upper tiers of the industrial value chain. As of 2025, 85 Chinese companies have been recognized as members of the global “Lighthouse Factory” network, representing 45 % of the total and ranking first worldwide (World Economic Forum, 2025). However, the sector’s digital technology foundation remains weak, facing challenges from lengthy industrial chains and complex production processes (Xinhua News Agency, 2024). Most traditional manufacturers are in the early stages of DT and generally remain in the middle and lower tiers of the value chain Bai et al. (2024), with their innovation potential yet to be fully realized (Caputo et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2025a). How manufacturing companies can effectively implement DT and unleash its innovative potential is critical to their survival and China’s high-quality and sustainable economic growth (Liu et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2025).

Essentially, DT is a systematic change wherein organizations introduce digital technologies to reform organizational systems and processes and reconstruct the logic of value creation (Vial, 2019), thereby achieving significant innovation capability. However, most manufacturing companies still face the dilemma of “knowing is easier than doing” (Wu et al., 2022). Owing to fears of failure and caution, most companies tend to adopt a conservative approach, applying digital technologies within their existing production modes and implementing DT only in familiar areas (Jones et al., 2021). According to Accenture (2023), only 2 % of Chinese companies—below the global average of 8 %—have adopted a fully reshaped digital strategy. This reflects methodological reductionism resulting from organizational inertia, which overlooks the emergent innovation of digital technologies. The results cannot be explained by known elements and are difficult to integrate into the existing organizational framework and daily practice. Companies may be uncertain or unwilling to accept these changes, resulting in internal behavioral tendencies of “dare not change” (risk aversion) and “do not want to change” (value doubt) (Sun et al., 2023). Therefore, the existing organizational framework and path dependencies may constrain the value of digital technology innovation (Roecker et al., 2017; Vial, 2019). In this context, companies must identify an appropriate entry point within a complex system.

Both structuration theory (Giddens, 1984; Sassen, 2008; Taylor, 2001) and actor-network theory (Latour, 1996) emphasize the interaction between humans and technology. Structuration theory further asserts that human agency plays a leading role, offering a means to realize the innovative potential of digital technologies, specifically by emphasizing human innovation. While digital technologies and human resources are unified, they also present opposing elements. Human resources are vital for company value creation (Schultz, 1961; Verhoef et al., 2021), and digital technologies have transformed the traditional organizational framework. The value creation process and outcomes of an organization are closely associated with and dependent on the skills and creativity of its human resources (Dremel et al., 2017; Vial, 2019). However, DT introduces new requirements and content for the skills and work of managers and employees (Hess et al., 2016; Yeow et al., 2018), and digitization may, in turn, compromise their interests or job stability. Owing to inertia and interest considerations, they may adopt a conservative or resistant attitude toward digital technologies. Research has demonstrated that approximately 70 % of DT projects fail to meet their targets because internal personnel’s interests and influence are neglected (Tabrizi et al., 2019). The complex interplay of digital technology and human resources reveals the key internal mechanism for successful innovation: the dynamic synergy between digital value creation and value distribution.

However, with the increasing severity and complexity of the global economic situation, most companies have begun to pursue cost reductions and efficiencies and view human capital centers as the core of cost control (Milanez et al., 2025). Consequently, human capital incentives may take a backseat, giving way to digitization strategies (Yang et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2025). Empirical findings suggest that robot adoption reduces employees’ pay (Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2020), resulting in tensions between human capital and digitization (Lin et al., 2025; Milanez et al., 2025; Tarafdar et al., 2015). Under these circumstances, digitization may reduce a company’s innovative capacity (Vial, 2019). Therefore, by building internal incentive systems aligned with new value creation networks, companies can effectively resolve the tension between the rigidity of digital technologies and existing organizational behavioral inertia (Stone et al., 2015). This approach can also reduce employees’ feelings of alienation and insecurity regarding technology and decrease their resistance to transformation (Chen et al., 2023). Moreover, companies can further activate employees’ agency, unleash the value-creating potential of talent, and facilitate the shift of internal members from passive recipients to active contributors in value creation.

The literature has explored the innovative value and mechanisms of DT and incentives for companies, such as the impact of DT on green innovation (Gaglio et al., 2022) and innovation efficiency (IE) (Lin & Xie, 2024). The role of compensation incentives—including equity incentives (Hu & Hong, 2023), positive employee treatment (Mao & Weathers, 2019), and CEO compensation incentives (Sheikh, 2012)—in fostering innovation within companies has also been thoroughly examined. However, most studies have examined the impact of DT or incentive systems on corporate innovation from an isolated perspective (Gaglio, 2022; Tran et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024), lacking a theoretical explanation and discussion of the overall effects from the perspective of interaction and often overlooking the collaboration between DT and incentive systems. Furthermore, existing studies have typically addressed only one or a few incentives, rather than considering the overall effects of the incentive system from a collaborative perspective (Villani et al., 2024). In particular, the dialogue between executive and employee incentives remains relatively fragmented (Faleye et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2024).

Moreover, owing to the emphasis on the independent effects of variables, numerous studies have employed traditional quantitative methods to isolate the “net effects” and mechanisms of factors influencing corporate innovation (Gaglio et al., 2022; Hua, 2025; Peng & Tao, 2022). However, these analytical models, which assume variable independence and average effects, struggle to explain the complex relationships and systemic emergence among multiple variables in innovation systems (Di Paola et al., 2025; Ragin, 2008; Thomann & Maggetti, 2020). Some studies have adopted a holistic approach, applying qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) to investigate how different configurations of conditional variables shape corporate innovation (Ding, 2022; Zheng et al., 2025). Although this approach addresses the limitations of traditional quantitative research, the simplification of causal complexity and lack of temporal analysis in QCA may obscure the dynamic evolution of causal relationships (Du et al., 2021, 2024; García-Castro & Ariño, 2016). To address this issue, García-Castro and Ariño (2016) introduced dynamic QCA, which incorporates a temporal dimension by decomposing consistency parameters and effectively resolves QCA’s limitations in analyzing the temporal sequence of causal relationships. Du et al. (2024) further proposed that mixed methods could be employed, treating configurations as independent or nearly independent subsystems for effect analysis.

Accordingly, this research systematically addresses the question of an effective DT innovation incentive system using a sample of China’s listed manufacturing companies from 2016 to 2023. It employs dynamic QCA and regression methods, combining incentive systems and DT to examine corporate IE. The study aims to address the following questions: (1) How can DT and organizational incentive systems be synergized to achieve high corporate IE? (2) What are the distinctive characteristics of these synergistic paths? This research makes the following three contributions: First, by introducing the concept of imbrication, it bridges previously separate analyses of technological adoption and incentive mechanisms, thereby enhancing the causal understanding of IE. Second, we develop the “DT–incentives” framework to identify multiple equivalent configurations for achieving high-level IE. This framework captures the synergistic interactions among DT, executive and employee incentives, and internal compensation gaps, moving beyond static or single-factor perspectives. Third, this study combines dynamic QCA and regression analysis to examine the innovation system, considering both overall emergence and the independent effects of subsystems. This hybrid approach addresses the limitations of traditional QCA, which is limited to static analysis, and regression analysis, which primarily examines net effects. It broadens the methodological approach to corporate innovation. This approach reveals temporal changes, company size differences, and marginal effects of different configurations on IE, making the study’s conclusions more realistic.

The subsequent sections are organized as follows: "Research framework and theoretical background" outlines the relevant theories, develops the analytical framework, and reviews the literature on each condition’s effects on and mechanisms of corporate innovation. "Data and methodology" describes the methodology, data, and variable definitions. "Dynamic QCA results" and "Regression analysis results" detail the process and results of the dynamic QCA and regression analysis, respectively. "Discussion" discusses the findings and compares them with existing research and theories. "Conclusion" concludes the study and outlines its implications and limitations.

Research framework and theoretical backgroundResearch framework constructionConceptual frameworkRegarding the relationship between human and material agency, structuration theory posits that human agency consistently holds a dominant position, while technology is viewed as a structurally passive tool whose value depends on how human agency adapts to and interprets new technology (Gefen et al., 2024; Giddens, 1984; Pfaff et al., 2023). However, with the continuous advancement of technologies such as AI, the prominence of technological subjectivity has become increasingly evident (D’Amato, 2025). Algorithms can even shape humans’ cognition and value orientation through reward mechanisms (Shani-Narkiss et al., 2025). Thus, structuration theory struggles to accurately depict the mutual influence between human and material agency in digital practices (Xie et al., 2021). Actor–network theory regards humans and technology as equal actors, exploring the communities they form together (Dattathrani & De’, 2023). Some scholars emphasize that technology functions as an active participant and shaper of organizational change instead of functioning merely as a passive tool (Owsley & Greenwood, 2024). However, its fully symmetrical perspective undermines the dominant role and scope of human responsibility in digital practices. Moreover, it fails to accurately depict the relationship between humans and technology (Hajli et al., 2022; Owsley & Greenwood, 2024), such as the excessive control algorithms exert over platform workers (Lin et al., 2025).

To address the limitations of the two theories, Ciborra (2006) and Leonardi (2011) introduced the concept of “imbrication,” which emphasizes both the dominant role of human agency and the active role of material agency, to describe the integration and interdependence of human and material agency. Leonardi (2011) likened this interwoven relationship to the arrangement of roof tiles, in which imbrices and tegulae overlap to form a unified structure. Heyder et al. (2023) further emphasized the interdependence and inseparability of human and material agency in this framework, arguing that neither can create value in isolation. The imbrication process may be antagonistic, reinforcing, or involve one party changing the other. Ultimately, a new balance is realized, which resolves the initial problem and may unlock new ways of working and business models, adding value to companies (Kindermann et al., 2024). For example, Wang et al. (2021) documented how a large casino resort in Macau repeatedly introduced, adapted, and upgraded its customer relations management systems over two decades. In the initial stage, employees leveraged the system’s affordances to optimize customer management; however, as the business expanded, functional limitations gradually constrained new service models. These constraints drove employees to implement a new round of system upgrades, and the upgraded system’s new capabilities reshaped employees’ work processes. This cycle of “humans driving technology → technology acting back on humans → repetition” reflects the entire process of imbrication. Thus, value generation results not only from technological upgrades but also from the ongoing reconstruction within human–technology imbrication (Heyder et al., 2023; Viktorelius et al., 2021).

Therefore, as companies continuously improve the digital level in the DT process, they must involve as many members as possible to integrate digital technology and human capital through reciprocal adaptation. Companies must promote a dynamic cycle of imbrication through incentive mechanisms. In this process, they must fully unleash the innovative value of digital technologies and the innovative potential of human capital, achieving synergistic effects that exceed the sum of individual contributions. Ultimately, this process creates and enhances company value, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Conceptual modelThe most important form of organizational incentive is monetary incentive. In corporate practice, it comprises the following two main components: executive and employee incentives. Executive incentives constitute a component of internal corporate governance and function as a key institutional basis for fostering innovation (Du & Ma, 2022). The two primary categories of executive incentives are those based on equity and compensation. Employee incentives are regarded as an important management practice, with compensation incentives and internal pay equity as key measures. Employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs) are primarily used to incentivize the core workforce in an organization. Notably, the incentives for executives and employees also include implicit incentives, such as on-the-job consumption. However, the considerations underlying these incentives rarely involve corporate innovation, suggesting that they may play a relatively limited role in corporate IE. Therefore, this study constructs a “DT + incentive system” framework from a configuration perspective. This framework explores the causal impact of a combination of six key conditions—namely, the degree of digitization (DD), executive equity incentive (ExeEI), executive compensation incentive (ExeCI), employee compensation incentive (EmpCI), ESOP, and pay gap (PG)—on corporate IE, as depicted in Fig. 2.

Theoretical backgroundDigital transformation and corporate innovationMost studies have demonstrated that DT can promote corporate innovation (Gaglio et al., 2022; Wen et al., 2022). First, digital technologies and technology clusters possess considerable data processing capabilities and can be employed to efficiently utilize and analyze data based on digital models. Accordingly, they mitigate the inherent uncertainty of the innovation process and enhance the efficiency with which resources are allocated and converted (Lin & Xie, 2024; Tang et al., 2023). Digital tools such as generative AI have become efficient work tools for employees (Bankins et al., 2024). Second, digital platforms such as office automation (OA) and enterprise resource planning (ERP) can integrate data from various departments, effectively promoting cooperation and knowledge sharing between research and development (R&D) and other departments (Lin & Xie, 2024). In doing so, they increase access to innovation resources and capabilities previously limited to a certain department (Peng & Tao, 2022). Production factors and information resources can flow quickly and efficiently across departments, considerably improving innovation processes and IE (Sivarajah et al., 2020). A digital platform can also attract participants from all segments of the supply chain. By establishing an innovation cooperation platform, companies, academic institutions, governments, and consumers can share information and technology, generating further correlation, spillover, and collaboration effects (Bereznoy et al., 2021). Consequently, they achieve both internal and external collaborative innovation (Lange et al., 2020). Third, digital inputs in manufacturing production processes can directly promote corporate innovation. Digital resources generated by digital technologies can function as new production factors in company operations. As new means of labor, digital technologies can be integrated into all stages of production, transforming and upgrading the entire process and enabling the creation of more intelligent products (Wang & Shao, 2024).

However, digital technologies do not necessarily result in increased business innovation (Chouaibi et al., 2022). Promoting DT involves significant risk; failure at any stage may result in higher transformation costs or complete failure, causing substantial losses for companies. Additionally, digital technologies must be fully integrated with other production factors to achieve positive outcomes. As previously noted, internal resistance to change exists, including executives’ concerns about transformation failure, employees’ fears of digital displacement, and “panoramic prison-style” assessment and supervision (Bhave et al., 2020). These negative effects may reduce overall organizational effectiveness (Stone et al., 2015).

Incentive system and corporate innovationExecutive incentives. Executives primarily affect innovation performance by shaping corporate governance (Chen et al., 2015). Principal–agent theory suggests that management has substantial discretionary power, and innovative projects with high investment, high risk, and long cycles may cause fluctuations in performance (Finkelstein & Hambrick, 1990; Magerakis, 2022). Consequently, executives may engage in risk-avoiding and prudent investment behaviors based on self-interest considerations (Bebchuk & Stole, 1993). However, innovation remains essential for companies’ long-term growth. Implementing incentive mechanisms that encourage executives to increase their risk tolerance and invest in R&D is fundamental to improving corporate innovation (Huang et al., 2023). Executive incentives primarily contain short-term incentives represented by compensation incentives and long-term incentives represented by equity incentives. Equity incentives offer an effective alliance mechanism by allowing executives to become shareholders, which ensures their participation in profit distribution and power stability. This structure encourages executives to prioritize the company’s long-term development and value enhancement (Balkin et al., 2000). However, the managerial entrenchment hypothesis suggests that when executives hold significant ownership, they may prefer non-innovative, lower-risk projects. Because personal wealth is closely associated with stock prices, executives tend to prioritize short-term market volatility and overlook the sustained value of innovative projects (Wang et al., 2024). Executive compensation incentives also have bidirectional effects under different influencing mechanisms. When executive compensation is linked to corporate performance, these incentives can reduce executives’ risk aversion and encourage participation in risky projects that benefit the company in the long term (Guo et al., 2020), thereby promoting corporate innovation. However, such incentives may also cause managers to prioritize short-term benefits (Cassell et al., 2012), leading them to resist innovative projects with high risk.

Employee incentives. Employees are both direct participants in and facilitators of organizational innovation (Chang et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2020). In China, employee incentives are predominantly derived from compensation (Yuan et al., 2023). Despite the evidence from numerous studies indicating that employee compensation benefits corporate innovation performance (Mao & Weathers, 2019; Villani et al., 2024), excessive incentives may lower innovation ability. Excessive compensation increases the company’s costs, and a compensation incentive system not linked to performance is ineffective for employees (Kachelmeier et al., 2024; Massingham et al., 2015). It may even demotivate active employees because of unfair incentives (Colquitt et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2015; Ye et al., 2023). Moreover, innovation involves considerable uncertainty, and a result-oriented appraisal system may not effectively motivate employees (Holmstrom, 1989). An ESOP is an important incentive mechanism for core employees. It ensures that core employees benefit from the company’s future earnings and enhances their risk tolerance and motivation to engage in innovation while improving teamwork and stability (Gamble, 2000; Liu et al., 2024). Additionally, ESOPs reduce the PG, promoting internal pay equity (Li et al., 2025b). However, ESOPs may lead to free riding (Oyer, 2004), and employees excluded from ESOPs may display negative behaviors due to pay inequity (Hao & Liang, 2022), which can create an innovation incentive environment that does not benefit the company.

Internal pay equity. According to the principle of diminishing marginal utility, a Pareto optimum exists in executive and employee incentive systems, where total returns from incentives are maximized. However, the evidence on the incentive relationship between employees and executives remains inconclusive. Social comparison theory (Adams, 1963) indicates that excessive internal PG can reduce work engagement and productivity by causing employees to perceive unfairness and deprivation, which weakens internal collaboration and lowers organizational productivity and overall performance (Bamberger et al., 2021; Cowherd & Levine, 1992; Han et al., 2024). However, tournament theory suggests that a hierarchical compensation system can also motivate executives and employees to work actively (Connelly et al., 2016). It is further suggested that these two theories can coexist in explaining how the pay gap relates to performance, indicating a nonlinear relationship between the two (Kim & Jang, 2023).

Data and methodologyMethodsThis study uses dynamic QCA and regression analysis to explore the causal relationship between six key antecedents and corporate IE. First, based on the configuration perspective, the research identifies multiple configuration paths that lead to high IE in companies using dynamic QCA. It captures changes in configurations across time and space through pooled, between, and within analyses (García-Castro & Ariño, 2016). Second, following Du et al. (2024) and a reductionist approach, the study treats different configurations as relatively independent subsystems, assigning the minimum membership degree of each case across all antecedent conditions as its value within the configuration. Regression analysis is then used to further assess the effect of different configurations on IE.

Data source and sampleConsistent with QCA data-collection principles, the research objects are China’s A-share listed manufacturing companies with continuous data from 2016 to 2023. The following samples are deleted: (1) those with incomplete data, (2) those labeled ST or *ST, and (3) those with average executive compensation equal to or less than average employee compensation. As IE exhibits a lag, the outcome variables are delayed by one treatment cycle (i.e., the six conditional variables are from 2016 to 2022, and IE is from 2017 to 2023). The data set includes 1387 case companies over eight consecutive years. IE data are from the CNRDS database, and the remaining data are from the CSMAR database.

MeasurementInnovation efficiencyCompared with patent grants and new product sales revenue, patent applications serve as a more accurate indicator of companies’ innovation output owing to their universality, stability, and absence of time lag (Quan & Yin, 2017). In the Chinese patent classification, the level of innovativeness decreases from invention to utility model to industrial design patents. Given the varying importance and contribution of these patents (Li et al., 2025a), this study calculated IE using the method of Quan and Yin (2017)) and Zhou et al. (2023). The number of applications for a company’s invention, utility model, and industrial design patents was weighted 3:2:1 and summed to represent the innovation output. Subsequently, the IE was obtained through Eq. (1):

Additionally, to more accurately assess the reliability of innovation output, we used (1) invention applications, (2) utility model and design applications, and (3) all patent applications as alternative measures of companies’ innovation output in the robustness analysis (Kong et al., 2017).

Degree of digitizationDegree of digitization (DD) refers to the extent of corporate DT. In recent years, Chinese scholars have measured DD using text analysis because DT involves not only technology adoption and data digitization but also a comprehensive strategic transformation of companies’ production and operations. Intuitive indicators, such as telecom expenditure and information investment, do not fully capture DD. Additionally, the annual report presents a company’s strategic position and business philosophy for the reporting year. As a major strategic decision, DT is necessarily reflected in the annual report. Many scholars agree that companies’ DD can be measured using digital word frequency in annual reports. Tu and Yan (2022) noted that, although some information in corporate annual reports may introduce measurement errors due to forward-looking factors, the widespread nature of these issues across most reports constitutes a systematic error. Therefore, we used CSMAR’s “Digital Transformation Research Database of Chinese Listed Companies” as the data source. Following the methodology of Wu et al. (2021), we selected five major digital libraries—AI, blockchain, cloud computing, big data, and digital technology applications—to represent corporate DD by adding 1 to the word frequencies and then taking the logarithm of the sum of these values. To further assess the robustness of this measure, we replaced other scholars’ thesaurus and construction method approaches and adopted the robustness testing method provided by Yuan et al. (2021).

Key incentive indicatorsIn this study, “executive” includes all supervisors, senior managers, and directors. To eliminate the impact of unpaid executives on calculating the average executive compensation, those without compensation are excluded from the management team size (Kong et al., 2017). Chinese listed companies are required to disclose executive and employee compensation in their financial statements (Dai et al., 2017). Therefore, following Kong et al. (2017, 2022), we calculated ExeCI and EmpCI as the total compensation of each group divided by its headcount, with the PG measured as ExeCI divided by EmpCI. The specific formulas are provided in Eqs. (2)–(4).

Additionally, ExeEI was measured as the ratio of executives’ shareholdings to total company shares (Guo & Li, 2025; Li et al., 2024). For ESOP, given the limited number of companies implementing such plans in the sample, we constructed a binary variable set to 1 when a company implemented an ESOP in the current year and 0 otherwise (Kim et al., 2025; Li et al., 2025b).

Calibration and descriptive statisticsAs ESOP is a binary variable, calibration is unnecessary. For the remaining variables, owing to the absence of suitable reference points and to minimize potential subjective bias, we use the direct calibration method (Ragin, 2008). The 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the variable serve as thresholds for full non-membership, crossover, and full membership, respectively. Since a calibrated membership score of 0.5 cannot be directly included in the calculation, all such values are adjusted to 0.501 (Fiss, 2011). See Table 1 for details.

Sample descriptive statistics and calibrations.

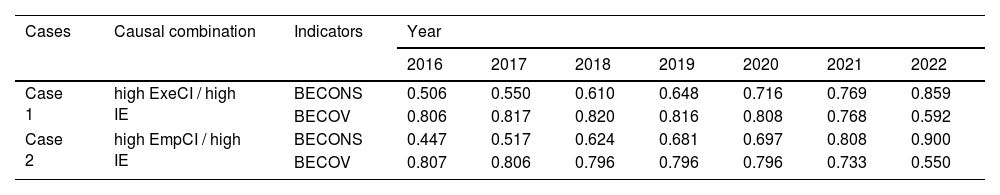

The necessary condition analysis tested whether IE constitutes a subset of a single antecedent condition. If the pooled consistency (POCONS) is greater than 0.9, the condition is considered necessary for IE (García-Castro & Ariño, 2016). As dynamic QCA was applied in this study, we also tested the reliability of consistency using between consistency (BECONS) and within consistency (WICONS), which assess temporal and case-based reliability, respectively. These assessments are based primarily on the adjusted distance of BECONS and WICONS. If the adjusted distance exceeds 0.2, POCONS is deemed unreliable, requiring further analysis. Table 2 shows the results.

Necessary analysis for high corporate IE.

Note: ∼ indicates the condition is absent.

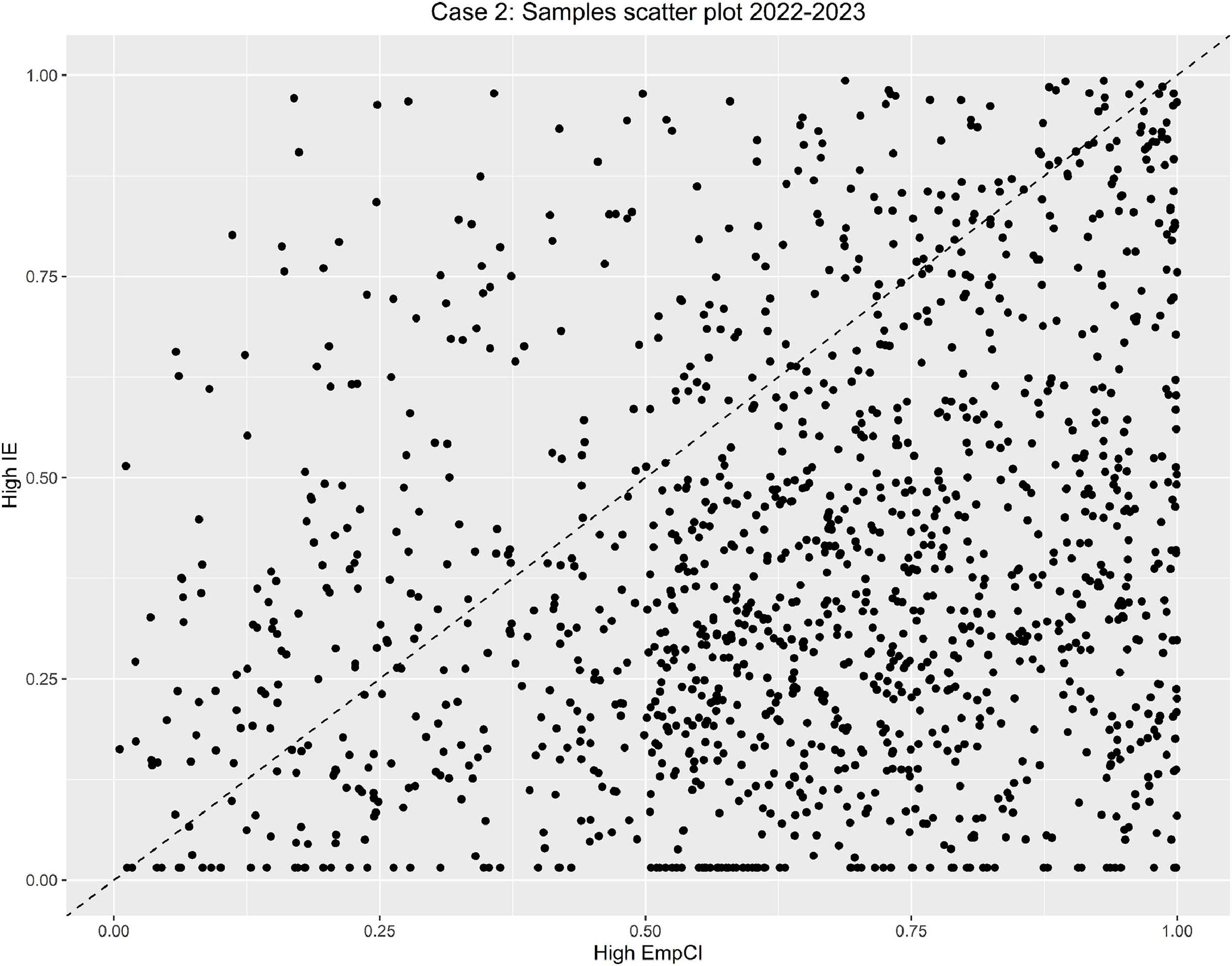

It can be observed that the POCONS of all antecedent conditions were below 0.9, indicating that no condition alone constituted a necessary condition for high IE. However, the BECONS adjusted distances for ExeCI and high EmpCI exceeded 0.2, necessitating further discussion. Table 3 shows the BECONS and between coverage (BECOV) of high ExeCI/high IE and high EmpCI/high IE across different years. The BECONS for high ExeCI/high IE remained below 0.9, indicating that this combination did not meet the necessity criterion. In contrast, the BECONS for high EmpCI/high IE in 2022–2023 exceeded 0.9, and the BECOV was also above 0.5; however, further verification using an X-Y scatter plot (Fig. 3) confirmed that it did not meet the necessity criterion. Fig. 4 illustrates the temporal changes in the BECONS adjusted distance for both cases, suggesting that the necessity of ExeCI and EmpCI for improving corporate IE has increased over time.

Causal combinations with BECONS adjusted distance > 0.2.

The sufficiency analysis is a key step in QCA. It examines whether different configurations constitute a subset of high IE; that is, when the antecedent configurations occur, high IE also occurs. In this study, the consistency threshold was set at 0.8 and the frequency threshold at 4. For the PRI value, Pappas and Woodside (2021) considered 0.5–0.7 to be moderate and acceptable. Following Ding (2022) and Patala et al. (2021), we set the PRI value at 0.6. The constructed truth table covered 9701 cases. The parsimonious solutions served as supplementary references, while intermediate solutions served as the main solutions. Table 4 presents the results.

Configurations for high IE.

Table 4 presents an overall solution consistency of 0.822, with each configuration’s consistency above 0.8. Thus, these configurations can be regarded as sufficient conditions for high IE. This study further categorizes the seven configurations into four solutions: Solution 1 (H1, H2), “executive compensation incentive digital innovation”; Solution 2 (H3), “employee compensation incentive digital innovation”; Solution 3 (H4, H5), “employee competition incentive innovation”; and Solution 4 (H6, H7), “executive–core employee collaborative incentive innovation.” Notably, among the seven configurations resulting in high IE, those with ESOP as a core condition show relatively low coverage. This is primarily attributed to only 1818 cases that implemented ESOP, accounting for a small proportion. In the analysis, the frequency threshold for case inclusion is set to 4, ensuring the stability of all solution configurations.

(1) Solution 1: Executive compensation incentive digital innovation

This solution is defined by the presence of ExeCI and DD as core conditions. In the current environment, DT is a significant trend in corporate innovation, and companies adopting this solution seek to enhance IE through proactive DT. Both DT and innovation activities, as top–down changes, involve considerable risk. Compensation incentives, as short-term measures, directly compensate executives for their current-period risks, reducing their concerns about recent business performance declines. Consequently, executives are more motivated to advance digital innovation. Additionally, high compensation signals shareholder support for digital innovation, allowing executives to access greater managerial power and resources, which further strengthens their commitment to digital innovation. As this solution relies primarily on ExeCI, it may lead to significant internal PGs (H2); however, this issue can be mitigated by increasing employee compensation (H1).

(2) Solution 2: Employee compensation incentive digital innovation

This solution is defined by the presence of EmpCI and DT as core conditions, with the absence of ExeEI and PG as core and peripheral conditions, respectively. This indicates companies’ emphasis on DT and employee engagement in innovation and DT. By providing high EmpCIs and maintaining non-high internal PGs, companies motivate most employees, ensure internal equity, promote positive team collaboration, and create an innovation-oriented environment at the employee level. This approach increases employees’ enthusiasm for corporate DT and improves collaborative efficiency. Furthermore, the low ExeEIs in this solution allow companies to avoid potential financial and operational constraints from long-term incentive plans. They also permit flexible compensation adjustments for executive teams in response to rapidly changing business strategies and market conditions, guiding executives toward effective strategic execution.

(3) Solution 3: Employee competition incentive innovation

This solution is defined by the presence of ESOP and PG as core conditions, and the absence of EmpCI as a peripheral condition, corresponding to configurations H4 and H5. Core employees are essential to corporate innovation, and ESOP incentives allow them to share future innovation benefits. This approach increases enthusiasm and engagement, reduces talent loss, and supports organizational stability. However, most ordinary employees receive relatively low overall compensation, and internal PGs are significant, indicating that companies adopt a hierarchical compensation system. Therefore, employees must engage in moderate competition to achieve higher compensation, which enables companies to utilize innovation resources efficiently. Configuration H4 also includes high DT to strengthen technical support, while configuration H5 adds high ExeEIs to motivate executive teams to promote innovation.

(4) Solution 4: Executive–core employee collaborative incentive innovation

This solution is defined by the presence of ExeEI and ESOP as core conditions, present in configurations H6 and H7. This solution features long-term and collaborative incentive mechanisms. The long-term mechanisms reduce risk aversion among executives and core employees, align their interests with innovation and DT, mitigate agency problems, and prevent negative effects from direct oversight. Collaborative incentives are achieved in two ways. Configuration H6 includes short-term compensation incentives for both groups, generating synergy and compensating for the limited short-term effect of equity incentives. Configuration H7 promotes internal equity through low executive compensation. This configuration also strengthens technical capabilities through high DT, while internal equity facilitates better integration of digital technologies and human capital.

Between resultsThe BECONS reflects the temporal effects of configurations. Table 4 shows that all seven configurations exhibit BECONS adjusted distances below 0.2, indicating no significant temporal effects. Fig. 5 illustrates the temporal consistency trends for each configuration, revealing that trends were relatively consistent across configurations. However, after 2020, consistency declined markedly and collectively across all configurations, rather than as a random shift. This pattern is plausibly attributed to the pandemic, which caused companies to suspend production and adopt conservative investment strategies. Notably, the consistency of configurations H3 and H6 remained above 0.75 during 2022–2023, demonstrating their exceptional applicability and the importance of broad-based incentives and distributive equity during crises.

Within resultsThe WICONS indicates the stability of configuration paths across cases. Table 4 shows that the WICONS adjusted distance for configuration 2 exceeds 0.2, suggesting the need to test the robustness of configurations across cases. As company size may significantly affect DT and incentive system design (Menz et al., 2021), this study measured company size by year-end total assets (Li et al., 2013); classified companies as large, medium, or small; and analyzed the WICONS for each group. As the WICONS for each configuration did not meet the normality assumption, the Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test was used. Table 5 presents the rank–sum test and paired comparison results, which show that configuration paths differ significantly in coverage across company sizes.

Rank-sum test results and paired comparison results.

Note: ***, **, and * correspond to 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % significance levels, respectively. Same as below.

Table 6 shows the coverage means of different configurations across company sizes. The horizontal analysis indicates that the coverage of each configuration across different company sizes is generally consistent with the overall results. However, the vertical analysis reveals significant differences in the same configuration paths across sizes. Large-sized companies show substantially higher coverage in H1 and H2 (corresponding to Solution 1) compared with medium- and small-sized companies. This is mainly because large-sized companies face greater scale and transformation challenges and depend heavily on top management teams to drive organizational change. Consequently, their incentive systems primarily target executives. The lower coverage of large-sized companies in H7 (where ExeCIs are relatively low) further substantiates this view.

Medium-sized companies show higher coverage in H4 and H5 (corresponding to Solution 3), primarily because their advantages are limited, despite having certain resources. Consequently, they rely more on internal competition to achieve efficient resource allocation and adopt long-term incentives to prevent talent loss. Additionally, the comparative results in Table 5 indicate that the difference in coverage between large- and medium-sized companies under this solution is not statistically significant. This suggests that large-sized companies also adopt internal competition–based incentive mechanisms, which primarily aim to mitigate the “big-company syndrome” and maintain organizational vitality.

Moreover, small-sized companies show higher coverage in H3 (corresponding to Solution 3), indicating a stronger focus on broad employee participation in DT. This is mainly because small-sized companies have limited resources and face greater external pressures, which require more emphasis on teamwork and value creation while avoiding fragmentation and resource waste from internal competition. Consequently, their incentive systems emphasize fairness and broad participation. In contrast, large-sized companies demonstrate the lowest coverage in this path, reflecting the excessively high costs of implementing such schemes in these organizations.

Finally, the coverage of H6 and H7 (corresponding to Solution 4) remains relatively consistent across company sizes (except for H7 in large-sized companies), suggesting their broad applicability. This solution demonstrates that combining multiple incentive mechanisms can motivate executives and employees, driving systematic improvements in innovation capacity while balancing costs and avoiding excessive internal competition.

Robustness testThis research uses four methods to test robustness. First, the raw consistency threshold is adjusted to 0.9, yielding outcomes similar to the original conclusions. Second, the PRI values are set to 0.7, resulting in four identical or similar configuration paths. Third, the DT calculation method is replaced with the thesaurus and approach described by Yuan et al. (2021), producing six configuration paths similar to those in this study. Finally, as previously noted, companies’ innovation output is replaced with three patent application measures in the robustness analysis (Kong et al., 2017). After this substitution, eight, five, and six configuration paths identical or similar to those in this study were obtained. Overall, the findings are robust.

Regression analysis resultsRegression analysisThe dynamic QCA identifies the effects of various configurations on high IE from a holistic perspective, but it does not explain the effects of configurations on IE. Therefore, this study examines the effect of different configurations on corporate IE using regression analysis. First, following the value assignment method of Du et al. (2024), the membership degree of each case in the configuration was calculated and used as the independent variable. Second, other conditions were included as control variables, along with state ownership, number of employees, and total assets. All variables were standardized to account for scale differences. Table 7 presents the regression results, which show that all configurations significantly increase IE at the 1 % level. Configurations H1 and H2 exhibit the highest marginal effects, indicating that ExeCI and DT are most effective in increasing IE in the Chinese market, with H3 closely following. H4, H5, H6, and H7 also show significant effects. The results indicate that the system formed by the synergy between DT and organizational incentive mechanisms substantially promotes IE. This effect is not a simple summation of the effects of individual conditions but an emergent systemic effect arising from the synergy of different conditions.

Influence of configurations on corporate IE.

This study uses two approaches to test robustness. First, the measurement of IE is replaced; all patent applications are recorded as innovation output (Quan & Yin, 2017), and the results are reported in Table 8. Second, the research sample is changed. Given the volatility of R&D investment, a 5 % truncation of the sample is conducted based on total R&D investment, with results shown in Table 9. The comprehensive analysis shows that the coefficients and significance of each configuration remain largely unchanged, confirming the robustness of the findings.

Robustness test: replace the calculation method of IE.

Robustness test: truncated treatment.

In recent years, DT has become essential for companies to maintain innovation competitiveness (Vial, 2019). However, achieving successful DT remains a major challenge for policymakers and researchers (Zhu et al., 2021). Many scholars emphasize the importance of DT and organizational incentives in promoting corporate innovation (Konopik et al., 2022; Verma et al., 2023; Vlahović et al., 2025). At the same time, some scholars discuss the “productivity paradox” of DT (Chouaibi et al., 2022; Thrassou et al., 2020) and the “ambivalence of incentives” (Islam et al., 2022; Yun & Linfeng, 2020). Related research also finds that resistance from organizational members is a key reason for DT failure (Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021; Shirish & Batuekueno, 2021; Vial, 2019). How to reconcile human agency and digital technologies has become crucial for unlocking innovation capabilities in DT. Nevertheless, as digital technologies become more intelligent, traditional theories increasingly struggle to explain human–technology interactions. Kim and Lee (2025) argued that future research should apply Leonardi’s (2011) concept of imbrication to clarify the complex relationship between human and digital systems. We build on this and extend the concept by emphasizing that imbrication requires promoting human agency through incentives, thereby creating a virtuous cycle of iterative upgrades. Based on this perspective, we propose a causal framework that captures the interplay between DT and organizational incentive systems in promoting IE. This approach allows for a clearer interpretation of the relationships among various elements, while avoiding reductionist single-mechanism explanations. Our framework aligns with that of Vlahović et al. (2025), who argued that digital technology should be integrated into a broader innovation ecosystem and that strategic management innovation is necessary to convert digital potential into tangible innovation outcomes, rather than treating it as an independent driver.

This study is the first to integrate DT, organizational incentive systems, and IE within a unified framework. The findings reveal that DT alone is insufficient to improve IE. This outcome aligns with the views of Meng et al. (2025), who argue that focusing only on DT does not generate intrinsic value for companies but requires the recognition of the complementarity between DT and other elements. However, this does not negate DT’s positive potential. Among the seven high IE configurations, DT is a core condition in five, indicating that our findings support the positive role of DT in fostering innovation (Gaglio et al., 2022; Lin & Xie, 2024). The study also finds that no single incentive mechanism can enhance innovation capability; however, the necessity of ExeCI and EmpCI in improving IE is increasingly evident. This conclusion contrasts with earlier views that equity incentives are more effective than compensation incentives in promoting innovation (Balkin et al., 2000; Holmstrom, 1989). This difference may be due to external and internal environmental uncertainties and the strong emphasis executives and employees place on short-term returns.

Nonetheless, our analysis indicates that DT is dispensable in configurations H5 and H6; this is mainly because its inherently transformative and disruptive nature (Eller et al., 2020; Ribeiro et al., 2023) may not be beneficial to companies from benefiting from it. Several scholars have identified drawbacks of DT, reporting that it leads to resistance within the organizational sociocultural systems (Cao et al., 2025; Nadkarni & Prügl, 2021; Shirish & Batuekueno, 2021; Vial, 2019). Butt (2024) conducted a qualitative study of three companies and found that digital strategies can cause cultural resistance. Organizational members perceive that these strategies concentrate power and interests at higher hierarchical levels, while threatening their job incentives and security. Moreover, they must bear additional burdens, such as upskilling. Many scholars argue that when safeguards and incentives are weak, organizational members are more inclined to view DT as a threat to their identity and autonomy, thereby provoking internal resistance, strategic failure, and declines in organizational performance (Cao et al., 2025; Frick et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2025b). Therefore, Butt (2024) proposed that, to maintain a competitive advantage, companies must continually update their internal sociotechnical systems to align with their strategy; the study further revealed that a complete incentive system is the prioritized mechanism for building internal consensus. Our research supports this perspective, emphasizing that the negative impacts of DT can be mitigated or offset through incentive systems, thereby unleashing the innovative capabilities of new systems. The regression analysis further shows that these configurational pathways produce systemic emergent effects, significantly improving corporate IE. This indicates that the interests of organizational members and digital systems have attained a new balance and that the new system has achieved human–technology synergy.

Liu et al. (2025), using data from Chinese listed companies (2007–2022), showed that DT has a positive causal effect on environmental innovation capacity, with ExeCI and EmpCI further strengthening this relationship. However, their study paid limited attention to the broader organizational incentive system and lacked a deep discussion of the relationship between incentives and DT, making their conclusions somewhat one-sided. In our study, in the paths emphasizing internal competition (configuration H4) and internal fairness (configuration H7), executive and employee compensation levels were relatively low, but high IE was still achieved through other well-matched incentive mechanisms. That being said, among all configuration paths, those involving the synergy of DT with ExeCI or EmpCI exhibited greater explanatory power, suggesting that compensation incentives are critical in the digital innovation system. Additionally, Yuan et al. (2023) argued that increasing employee compensation is essential for sustaining companies’ core competitiveness, and our results complement this view. The between-group analysis of the seven configurations showed that those achieving employee incentives or internal fairness (configurations H3 and H6) maintained strong IE even during external shocks, sometimes without relying on DT, highlighting the unique value of employee incentives.

We condensed the seven configurations into four solutions and identified company size heterogeneity. Large-sized companies exhibited the highest coverage in Solution 1 (executive compensation incentive digital innovation). Berbel-Vera et al. (2022) noted that many DT failures stem from a lack of top management team (TMT) support. Owing to their scale, large-sized companies require TMT coordination to fully harness the innovative potential of digital technologies; therefore, Solution 1 corroborates the view that TMTs are crucial to DT success (Firk et al., 2022). In contrast, medium-sized companies exhibited the highest coverage in Solution 3 (employee competition incentive innovation). This finding contrasts with Dutta and Fan (2025), who found that internal competition may reduce early-stage innovation motivation and overall innovation output. We suggest that this difference may occur because Solution 3 mitigates the negative effects of competition on core members by introducing equity incentives, which increase their competitive motivation. Moreover, given recent external pressures and internal demands of DT, such companies may prioritize short-term innovation output mechanisms to maximize outcomes. Meanwhile, small-sized companies exhibited the highest coverage in Solution 2. Graham et al. (2002) found that employees in small companies have a stronger influence on performance, leading these companies to rely more on their workforce. Due to their flat structures, these companies also tend to treat employees equally in pay and rewards. Solution 2 supports this perspective and demonstrates that emphasizing EmpCIs and internal fairness in DT processes can enhance digital innovation systems more effectively. Solution 4, which emphasizes universal incentives and fairness, shows no significant variation across company sizes, supporting the fairness theory (Fehr & Schmidt, 1999). Katz et al. (2000) emphasized that even in an era of rapid technological development, human resources remain the key to business success. Zhu et al. (2021) further argued that DT has human-oriented characteristics. Our study finds that even in the contemporary context of increasingly intelligent digital technologies, such technologies alone cannot create value for companies. The value of digital technology relies on human agency for realization, whereas the value of organizational members requires digital technology for further enhancement. The integrated system of digital and incentive mechanisms provides unique explanatory power in improving corporate IE, highlighting its emergent value. Therefore, we recommend a more systematic approach to DT and greater recognition of its synergy with organizational incentives.

ConclusionThis study develops a research framework integrating DT and the five core incentive mechanisms by drawing on panel data of A-share listed manufacturing companies from 2016 to 2023. We systematically examine the causal relationship between the “DT–incentives” system and corporate IE using dynamic QCA and regression analysis. The findings are as follows. First, neither DT nor any single incentive mechanism is necessary for high corporate IE, but the necessity of ExeCIs and EmpCIs has increased over time. Second, the sufficiency analysis identifies seven configurations to achieve high corporate IE, which can be categorized into four solutions: executive compensation incentive digital innovation (Solution 1), employee compensation incentive digital innovation (Solution 2), employee competition incentive innovation (Solution 3), and executive–core employee collaborative incentive innovation (Solution 4). Third, the between-group analysis reveals that configurations H3 and H6 remain robust over time, maintaining high consistency even under external shocks. The within-group analysis reveals that large-, medium-, and small-sized companies have the highest coverage in Solutions 1, 3, and 2, respectively, while coverage for Solution 4 is relatively consistent across company sizes. Fourth, the regression results indicate that all solutions significantly enhance IE, with Solutions 1 and 2 demonstrating the strongest explanatory power, followed by Solutions 3 and 4.

Management implicationsThis study offers three practical suggestions. First, improving IE through DT alone is challenging; companies must supplement DT with suitable incentive mechanisms. In resource allocation, companies should strategically balance DT and organizational incentives, avoiding a one-sided pursuit of transformation that compromises members’ interests. Instead, they should enhance the value-creation capacity of organizational members through digitization. Given the complex and dynamic internal and external environment, compensation incentives, as a direct and immediate incentive mechanism, can often more effectively alleviate executives’ and ordinary employees’ negative emotions and stimulate their enthusiasm.

Second, companies should choose differentiated strategic plans based on their size, particularly focusing on the synergy between DT and key group incentives. Large-sized companies are better suited to Solution 1, where the incentive system should prioritize executive incentives to enhance executives’ roles in overall planning and coordination during the transformation. On this basis, EmpCI can then be added to mobilize broader employee participation. Additionally, introducing moderate internal competition can help maintain organizational vitality. Medium-sized companies are more aligned with Solution 3. Companies can stimulate moderate competition among organizational members through differentiated compensation mechanisms to improve resource utilization and by implementing long-term incentive mechanisms (e.g., ESOPs) to maintain core team stability. Solution 2 is more suitable for small-sized companies. Companies should avoid excessive internal competition in the transformation process and highlight employee motivation and internal fairness, thus fostering the enthusiasm of most members and promoting DT and IE. Furthermore, regardless of size, companies can balance incentive efficiency and transformation costs through diverse combinations of incentive mechanisms (e.g., combining ESOPs with internal distribution fairness) to improve corporate IE.

Finally, companies should recognize that transformation is a continuous process and that the synergy between organizational members and digital technology will continue to evolve. Companies are advised to establish dedicated institutions and key positions, such as Chief Digital Officer, to integrate internal and external resources. This approach can help maintain steady progress in transformation and prevent deviations during implementation. Companies should also implement mechanisms to regularly assess changes in digital technology demand, evaluate the synchronization of incentives with transformation practices, and monitor potential risks in real time. These measures can enable companies to adjust policies promptly, capture emerging opportunities, and support innovation and long-term development.

Limitations and future researchThis study has several limitations. First, in addition to the key incentives mentioned above, other factors, such as paid leave, insurance, and corporate pensions, may also affect IE. However, due to limitations in measurement methodology and data availability, these factors were not included. Future research could develop a more comprehensive analysis system. Second, this study primarily examined internal factors affecting corporate innovation, while external factors were not considered. Future research could incorporate relevant external conditions or further subgroup analyses to identify additional factors influencing corporate innovation. Finally, similar to other studies using QCA, this study faced challenges in conducting more in-depth qualitative analysis. Subsequent research could collect additional information based on QCA and use case studies to analyze the intrinsic mechanisms for achieving high IE, thereby improving the authenticity and reliability of the conclusions.

FundingThis work was supported by Research Center of Intelligent Accounting (23ckzx03), Postgraduate Scientific Research Innovation Project of Changsha University of Science and Technology (CLKYCX24061) and Key Project of National Social Science Foundation of China (24AKS016).

Role of the funding sourceThe funding source only provided financial support.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHaixiong Deng: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Fang Yang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Wei Huang: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.