Firms are facing a substantial challenge in their journey towards a twin transformation to achieve greater environmental sustainability and digitalization simultaneously. Research lacks a deeper understanding on how firms respond to the need for a twin transformation. This study examines resources and capabilities that drive the green, digital, or twin transformation, in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Utilizing cross-sectional data from a sample of 7531 German firms sourced from the KfW SME panel, we conduct probit analysis to empirically test our hypotheses. Based on the different patterns observed with respect to the strategic orientation of a firm, we identify three distinct clusters: (1) firms solely prioritizing digitalization, which benefit primarily from size (number of employees and investments) and are situated in cities with access to a large number of graduates; (2) those emphasizing sustainability, typically smaller in scale with limited access to graduates and the tendency to be located in less densely populated areas; and (3) firms engaging in twin transformation, exhibiting similar characteristics to those focused on digitalization but possessing more experience and often being older. We find that the presence of college graduates as well as regular innovation activities have a significantly positive impact on digitalization, but a negative one on sustainability. This study contributes to research on understanding the strategic orientation of SMEs choosing between digitalization, environmental sustainability, and twin transformation, focusing on firm size as well as resources and capabilities. JEL Codes: D22, L21, O14, O32, R11

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are fundamental drivers of economic growth and innovation, playing a pivotal role across industries worldwide. In recent years, the business landscape has undergone profound transformations, mainly due to the rapid advancement of digital technologies and an increasing awareness of the imperative of sustainability. Many firms are facing the challenge of implementing a twin transformation—digitalization and environmental sustainability—considered a fundamental element for future business success, which demands updated strategies, action, and innovation (Kürpick et al., 2023). According to the European Union, “Successfully managing the green and digital ‘twin’ transitions is the cornerstone for delivering a sustainable, fair, and competitive future” (Muench et al., 2022, p.5). The two transformations differ in their nature and impact on firms. Digitalization is primarily driven by technological opportunities and competitive pressure, whereas strategies for environmental sustainability are often shaped by regulations and stakeholder expectations. However, both entail challenges requiring strategic adjustments by firms to reshape their innovation strategies, in turn impacting their resource allocation and capability requirements.

Many large firms are equipped with significant resources to sense and monitor relevant opportunities, and tackle both challenges simultaneously. They subsequently devote operational and research and development (R&D) resources to both digitalization and sustainability, and have relevant project management and strategic roadmaps to implement solutions. By contrast, SMEs have to act differently, especially due to their financial limitations, imperfect monitoring of changes in the business environment, and the resultant uncertainty, as they face challenges in deciding and successfully pursuing a strategic orientation towards sustainability, or digitalization, or both in an integrated manner (Smallbone et al., 2012; Denicolai et al., 2021). SMEs (<250 employees and EUR 50 million in revenues) comprise over 99 % of all businesses in Germany (Institut für Mittelstandsforschung Bonn, 2024). Despite their economic significance, many German SMEs face enormous challenges in digital transformation—in finding skilled employees, developing new business models, or transforming existing businesses (Bitkom, 2024). Additionally, ambitious national sustainability goals require these firms to quickly adopt eco-friendly practices (German Federal Government, 2021). However, resource constraints typically force SMEs to prioritize daily business over long-term digital and sustainability investments. Therefore, addressing the twin transformation is crucial for SMEs, as digitalization can improve operational efficiency and sustainability efforts and sustainable practices can open new market opportunities and ensure long-term competitiveness.

Firms’ strategic orientations represent guiding principles for appropriate actions to achieve superior firm performance (Hakala, 2011). The literature focuses on strategic orientations towards digitalization (Kindermann et al., 2021) and sustainability (Danso et al., 2019) separately, and research on the strategic orientation towards twin transformation is scarce. The theory of strategic orientation was applied for the first time to twin transformation by Ardito et al. (2021). The effective integration of digitalization and sustainability transformation could create a competitive advantage and superior performance for firms (Bartolacci et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2022). However, this effect is dependent on firm size, as large firms have the ability to devote greater resources to such projects (Broccardo et al., 2023). In the context of SMEs, Ardito et al. (2021), among the first to distinguish between digitalization and sustainability as strategic orientations of a firm, have analyzed their effect on innovation performance. The literature has also identified different drivers of digitalization and sustainability in SMEs. An empirical analysis by Omrani et al. (2022) established that technology context and existing levels of innovation, followed by corporate regulations, available skills, and financial resources as the primary forces behind digital technology adoption. Similarly, Eller et al. (2020) show that IT resources, employee skills, and a digital strategy have a significantly positive effect on firm digitalization. In terms of sustainability, Yadav et al.’s (2018) literature review lists various external (role of stakeholders and tangibility of the sector) as well as internal (employees, organizational culture, reputation, strategic intent, capabilities and firm size) drivers. A research stream is dedicated to digitalization’s enabling effect to achieve sustainability (for an overview on SMEs, see Guandalini, 2022). Despite the importance of digitalization and sustainability strategies as well as their integration for SMEs, the literature lacks consistent findings and robust patterns. Some key empirical gaps exist, such as whether transformations are addressed in parallel or sequentially, how firms assign resources and build capabilities to successfully implement both transformations simultaneously, how firm size influences strategic orientations, and if a firm's overall innovative capability determines the success of a twin transformation.

The present study aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of the strategic orientation of SMEs towards digitalization and environmental sustainability, focusing on firm size as well as resources and capabilities. Our study leans on and extends Ardito et al.’s (2021) research by exploring the basic strategies of SMEs towards digitalization and sustainability. We believe that these discussions are crucial for managers and policymakers to successfully adapt to the challenges resulting from digitalization and sustainability simultaneously. Accordingly, the main research question is formulated: How do resources and innovation efforts influence the strategic orientation of German SMEs towards digitalization and/or environmental sustainability?

This study focuses on German SMEs because they provide an analytically tractable and policy-relevant setting for twin transformation. First, we leverage access to firm-level microdata from KfW, which offers granular and comparable measures of digitalization and environmental strategies with broad coverage across sectors and size classes, enabling lower measurement errors and enhanced internal validity. Second, Germany’s SME sector is a prototypical snapshot of the European SME landscape. Firms operate under the EU’s common sustainability and digitalization architecture and face similar technology-driven competitive pressures, while spanning a diversified mix of manufacturing and knowledge-intensive services. Studying one EU member state provides constant key institutional features (single-market rules, competition policy and sustainability reporting requirements) and sharpens inferences on the mechanisms through which technology opportunities and regulatory pressures jointly shape firm strategy. Thus, the choice of Germany maximizes external relevance to other member states subject to the same regulatory environment, even if sectoral composition and factor endowments may vary. We acknowledge that external validity beyond Germany (and beyond SMEs) is necessarily limited and that our results should not be mechanically generalized. Nevertheless, by delivering a high-resolution baseline within a representative EU context, this analysis provides a rigorous empirical foundation and a transparent template for subsequent cross-country replication and out-of-sample tests of twin-transformation mechanisms.

We identify three distinct clusters focusing on either sustainability, or digitalization, or both, representing three different strategic orientations with distinct patterns: (1) some firms solely prioritize digitalization – these benefit primarily from size (in number of employees and investments) and are situated in cities with access to a high number of graduates; (2) firms emphasizing sustainability are typically smaller, have limited access to graduates, and tend to be located in less densely populated areas; and (3) firms engaging in twin transformation that exhibit similar characteristics to those focused on digitalization, but possess more experience and are often older.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of challenges and strategic orientation for digital, sustainable, and twin transformation in SMEs, and develops the research hypotheses. Section 3 provides the research methodology, data collection process, and description of variables. Section 4 presents the results of our empirical analysis, Section 5 discusses the key findings and Section 6, the managerial implications. Section 7 outlines the limitations and further research scope and concludes the paper.

Theoretical background and hypothesesA comprehensive theoretical framework to support straightforward empirical analysis of twin transformation processes within SMEs is lacking. Whereas strategic orientations are a well-researched field in management literature (Hakala, 2011), twin transformation is a fragmented field lacking a unified theory and even clear definitions. To address this gap, we synthesize the findings from recent empirical studies on digital transformation, sustainable transformation, and the interplay of these processes. By putting together insights from these diverse research streams, we provide an overview towards a better understanding of twin transformation in SMEs, offering a basis for future theoretical models and empirical analyses.

Based on Ardito et al. (2021), we analyze the transformations towards digitalization or sustainability in SMEs in terms of strategic orientation. Barney (1991) put forth the VRIN model, explaining that the resources of a firm must be valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable to create competitiveness and sustained competitive advantage. Additionally, the theory of dynamic capabilities, introduced by Teece et al. (1997) and Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), emphasizes the importance of a firms’ ability to generate or improve internal and external capabilities to deal with changing environments and achieve superior performance (Fernandes et al., 2024). While dynamic capabilities are measured and collected for large companies, they are more difficult to be identified and measured for SMEs (Arend, 2014; Dangelico et al., 2017). However, recent research highlights the importance and positive effect of dynamic capabilities for digitalization (Münter, 2023) and sustainability (Eikelenboom & de Jong, 2019) in SMEs.

The strategic orientation of a firm—for example, the focus on digitalization or sustainability—represents an intangible resource that depends on a firm’s diverse capabilities (Ardito et al., 2021). Both digital orientation (e.g., Bendig et al., 2023) and environmental sustainability orientation (e.g., Roxas et al., 2017) can lead to improved firm performance. To select and successfully implement a strategic orientation to gain a competitive advantage, firms must further analyze their internal resources and capabilities (Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2003) and focus on the microfoundations to determine interdependencies between individuals and the firm (Zhao & He, 2022).

Knowledge is one asset that firms need to acquire to effectively use other resources within the firm, with knowledge management positively contributing to strategic orientation (Ferraresi et al., 2012). Knowledge-based theory of the firm portrays different dimensions, namely recognition, access, assimilation, transfer and utilization of knowledge (Grant, 1996). To be successful, SMEs must focus on combining external knowledge, typically viewed in terms of absorptive capacity, and internal knowledge created by human resources (Maes & Sels, 2014). Drawing on the resource-based view perspective (Barney, 1991) and dynamic capabilities (Teece et al., 1997), with a focus on knowledge acquisition opportunities, this study analyzes how the geographic location of the firm as well as human capital and innovation activities influence a firms’ strategic orientation towards digitalization, or sustainability, or twin transformation.

SMEs and digitalizationWith the rise of digital technologies (software and devices, e.g., Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence), firms are able to address objectives like efficiency, customer experience, innovation, and competitive advantage through digital transformation (Münter, 2024), a complex, ongoing process that involves integrating digital technology into all aspects of a business (Tang, 2021). It involves the use of new digital technologies to improve customer experience, streamline operations, and create new business models (Vial, 2021). Nevertheless, a consensus regarding the precise definition of digital transformation and the challenges (Gersch & Sundermeier, 2019; Gong & Ribiere, 2021) is absent. Digital transformation is a strategic response to disruptions caused by digital technologies; it requires the development of dynamic capabilities (Warner & Wäger, 2019; Hanelt et al., 2021; AlNuaimi, 2022; Khatami et al., 2024), with implications for organizational structures and performance metrics (Verhoef et al., 2021). Hence, it is not merely about adopting new technologies but reimagining organizations, business processes, culture, and customer experiences in the context of the digital era.

SMEs often face challenges in adopting and integrating digital technologies such as cyber-physical systems, artificial intelligence, IoT, data analytics, and digital multi-sided markets (Kallmuenzer et al., 2024). The transition towards IoT involves significant investments and changes in organizational processes (Schallmo et al., 2017; Münter, 2023). The fourth industrial revolution is essentially driven by knowledge- and technology-based innovations ("science-based" and "technology-push"), that is, academic employees in R&D departments of companies or scientific research institutions, and universities create the basis for innovations (Dosi et al., 2008; OECD, 2019, 2020). Around 90 % of German SMEs describe their digitalization initiatives as being driven by technological opportunities, while only around 30 % argue that they are driven by customer demand (Zimmermann, 2021).

Studies have highlighted the critical role of dynamic digital capabilities, organizational culture, and readiness in driving digital innovation in SMEs (e.g., Wang & Costello, 2009; Münter et al., 2023). These factors are further influenced by market dynamics, resource availability, and innovation orientation (Ramdani et al., 2022; Ćirović et al., 2025). The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs), particularly in intra- and inter-organizational processes, significantly improves innovation performance (Scuotto et al., 2017). Furthermore, the allocation of resources for business model experimentation and strategy implementation can enhance the performance of SMEs undergoing digital transformation (Bouwman et al., 2019). The importance of digital skills, social media engagement, and organizational agility in improving SME performance has also been emphasized (Rozak et al., 2021). Finally, the adoption of digital technologies can enable SMEs to achieve sustainable profitability, as well as environmental sustainability (Philbin et al., 2022).

Research consistently points to a positive relationship between SMEs’ proximity to research institutions and universities and their digital innovations. Sternberg (1999) as well as Ratchukool and Igel (2018) found that spatial and multidimensional proximity play a significant role in establishing innovative linkages. Piterou and Birch (2016) and MacPherson (1998) support this argument, highlighting the benefits of university-based incubators, student internships, and academic-industry linkages in enhancing SME innovation. Lasagni (2012) and Albaladejo and Romjin (2000) emphasize the importance of SMEs' relationships with innovative suppliers, users, customers, laboratories, and research institutes. Molina-Morales et al. (2014) and Scuotto et al. (2017) provide a more detailed view, suggesting that while cognitive proximity and ICTs can enhance innovation performance, an excess of geographical proximity may limit access to new knowledge. Furthermore, regarding the geographic location of a firm, rural SMEs face numerous barriers to adopt new technology (for an overview, see Fanelli 2021). Still, rural SMEs face a digital divide as they continue to lag in adopting state-of-the-art web and social media marketing practices (Richmond et al., 2017).

Digital technologies change the tasks of employees by partially substituting routine assignments and complementing complex activities, which in turn raises demand for human skills in the form of college-educated workers (Autor et al., 2003). However, technology firms require specific skills and employee profiles that are often difficult to find (Goulart et al., 2022). Research is exploring the relevant skills that higher education institutions must convey to students to match the IT job market demands, highlighting the importance of educated employees for successful digital transformation (Rêgo et al., 2023). Cirillo et al. (2021) find that human capital, measured by education attainment levels, has a positive influence on the adoption of digital technology. Similarly, Doms et al. (1997) identify that the adoption of new technologies in the manufacturing sector is positively correlated to a skilled workforce, both pre- and post-adoption. Arendt (2008) finds that for SMEs, the barriers to ICT adoption mostly stem from a lack of knowledge, education, and skills (“skills access”) rather than access to IT (“material access”), in line with research underscoring the importance of digital capabilities for SME digitalization and technology adoption (e.g., Cragg et al., 2011; Southern & Tilley, 2000).

The relationship between innovation and digitalization in firms is dynamic and reciprocal, with digitalization enabling new forms of innovation, and innovation driving the adoption of digital technologies in firms. Empirical research shows that a firm’s innovativeness has a significantly positive relationship with both current and future adoption of digital technologies (Sichoongwe, 2023). Brodny and Tutak (2024) analyze EU-27 countries and find a significant relationship between the innovativeness of firms and their digitalization. Fernández-Portillo et al. (2022) underline that digitalization alone is not enough to increase a firm's financial performance, but must be aligned with a clear innovation strategy. Firms that prioritize innovation tend to be more agile and adaptable, enabling them to respond quickly to changes in technology and market demand (Tidd & Bessant, 2020). Furthermore, embracing innovation often fosters a culture of experimentation within organizations, encouraging employees to explore new digital tools, platforms, and business models, driving digital transformation initiatives (Thomke, 2020).

The digital transformation of SMEs is shaped by various contextual and organizational factors that determine their capacity to adopt and integrate digital technologies. Recapitulating the aforementioned concepts, geographic location (H1), human capital (H2), and innovation activities (H3) emerge as key enablers influencing SMEs’ strategic orientation toward digitalization, yielding the following hypotheses:

H1a SMEs located in urban areas execute more digitalization efforts than SMEs located in rural areas.

H2a Employing graduates has a positive effect on SMEs’ digitalization efforts.

H3a Innovation activities have a positive effect on SMEs’ digitalization efforts.

Sustainability is a complex and multifaceted concept that includes the need to meet present requirements without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same (Giovannoni & Fabietti, 2013). Sharma and Khanna (2014) and Kerekes et al. (2018) highlight the importance of responsible decision-making and the need to balance economic, social, and environmental dimensions. Given the focus of this study, we restrict our analysis to environmental sustainability. Morelli (2011) and Callicott (1997) emphasize the interdependence of human activity and ecological health, with the latter proposing a definition that prioritizes the health of ecosystems.

Firms are increasingly addressing environmental sustainability through dedicated R&D efforts, driven by a combination of market forces and regulatory frameworks (Zhang et al., 2008; Centobelli et al., 2021). These efforts cover a wide range of areas, including renewable energy technologies, sustainable materials, waste reduction strategies, and eco-efficient production processes. By focusing on R&D, firms seek to enhance their environmental performance, reduce their ecological footprint, and gain a competitive edge in markets increasingly oriented towards sustainability. The commitment to environmental sustainability is reinforced by legislation and regulation at both national and supranational levels in Europe. Directives such as the European Union's Renewable Energy Directive, Waste Framework Directive, and Circular Economy Action Plan set ambitious targets and standards for environmental protection, resource efficiency, and carbon reduction. Additionally, expanding the scope of CO2 trading (the EU ETS) significantly impacts firms' environmental sustainability efforts by increasing financial incentives for emissions reduction, and driving innovation in low-carbon technologies (Calel & Dechezleprêtre, 2016; Flori et al., 2024).

SMEs may face challenges in aligning their operations with sustainability goals and coping with evolving environmental standards (Jabbour et al., 2015; Hahn et al., 2015). Recent research finds a mostly positive relationship between sustainability innovation and firm size, with larger firms often benefiting relatively more from external knowledge and green process innovation (Martínez‐Ros & Kunapatarawong, 2019). However, the specific impact of firm size on the relationship between sustainability innovation and firm performance is less clear, with some studies suggesting that smaller firms may benefit more from green innovation investments (Lin et al., 2019), while some others highlight the importance of firm competitiveness in mediating this relationship (Le & Ikram, 2022).

Much research has explored the empirical connection between SMEs and sustainability innovation, specifically the drivers and performance implications. Bos-Brouwers (2010) and Triguero et al. (2016) provide insights into the types of sustainable innovation activities and the factors influencing eco-innovative intensity, respectively. Cuerva et al. (2014) and Triguero et al. (2016) find that technological capabilities are a key factor, with the former also identifying quality management systems and the latter establishing market power and firm-specific networks as determinants. Klewitz and Hansen (2014) and Chen and Liu (2020) focus on the role of different parties and customer participation in green product innovation. Baeshen et al. (2021) underscore the positive influence of green absorptive capacity, sustainable human capital, and organizational support on green innovation, with a stronger relationship in medium-sized firms. Singh et al. (2016) and Jun et al. (2021) emphasize the role of internal and external innovation drivers in different green innovations, with the former finding a significant positive impact on firm performance. Muangmee et al. (2021) bring out the importance of green innovation in the automotive parts industry, with green entrepreneurial orientation significantly influencing green innovation and sustainable business performance. Furthermore, Yacob et al. (2019) find that green initiatives, particularly in energy management, water conservation, and waste management, are positively related to environmental sustainability in Malaysian manufacturing SMEs. While both Le and Ikram (2022) and Rustiarini et al. (2022) highlight the positive impact of sustainability innovation on firm competitiveness and performance, the latter further identify green innovation as a mediator between intellectual capital and SME sustainability as well as financial performance.

For environmental sustainability, absorptive capacity emerges as a robust predictor of sustainable capabilities and green innovation adoption (Pacheco et al., 2018; Aboelmaged & Hashem, 2019). While sustainable human capital shows no significant impact, sustainable orientation and collaboration capabilities are identified as influential determinants and mediators. Albort-Morant et al. (2018) investigate connections among the knowledge base, relationship learning, and green innovation performance, revealing a positive and significant mediating effect of relationship learning on the link between knowledge base and green innovation performance. Therefore, fostering robust relationships with stakeholders is crucial for assimilating, transferring, and adapting new knowledge, ultimately enhancing green innovation performance (Di Vaio et al., 2020). Similarly, collaboration with research institutes (Triguero et al., 2013; Cuerva et al., 2014) and networks (Triguero, 2016) are pivotal for green products. Supporting the discussion on proximity to knowledge, Purwandani and Michaud (2021) find that firms located in urban areas are more accustomed to using green business practices than firms in rural areas.

To successfully implement a sustainability strategy, a firm needs an infrastructure that encourages a corporate culture built on sustainability (Galpin et al., 2015). Aligning the corporate culture with environmental responsibility is strongly influenced by employees' concerns and awareness (Fernández et al., 2003). In CSR initiatives, employees take on a crucial facilitator role, as firms’ actions are mirrored by the attitudes of the workforce (Kallmuenzer et al., 2023). A literature review by Sern et al. (2018) outlines different green skills in demand with various industrial sectors, uncovering three dimensions of green skills: knowledge, skills/abilities, and attitude/values. Universities play an important role in shaping a sustainable economy by creating and developing sustainability competencies in future graduates. Wolf (2013) uncovers a positive relationship between employee qualification for sustainability and firm performance.

The relationship between innovation and sustainability has seen growing interest from the academic research community. Firms largely recognize the importance of innovations being guided by sustainability principles—for example, in the form of sustainability-oriented innovations (Adams et al., 2016). A large-scale meta-analysis conducted by Kuzma et al. (2020) concludes that innovation has a positive impact on firm performance in all three sustainability dimensions: environmental, social, and economic. Islam et al.'s (2018) research revealed a strong and positive correlation between innovation and sustainability, bolstering the claim that firms must innovate, create new products, rethink old ones, and spend money on R&D to achieve their sustainability goals. Bamgbade et al. (2017) show mixed results for construction firms as even though the innovativeness of the manufacturing process has a positive effect on environmental sustainability adoption, this effect could not be confirmed for product innovativeness. For SMEs, all innovation capabilities—namely product, process, service and marketing—have a significantly positive relationship with sustainability (Hanaysha et al., 2022).

The sustainable transformation of SMEs is influenced by a range of contextual and organizational determinants that influence the capacity to adopt and integrate environmental sustainability. Among these, geographic location (H1), human capital (H2), and innovation activities (H3) emerge as key enablers that shape SMEs’ strategic orientation toward sustainability. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1b SMEs located in urban areas execute more sustainability efforts than SMEs located in rural areas.

H2b Employing graduates has a positive effect on SMEs’ sustainability efforts.

H3b Innovation activities have a positive effect on SMEs’ sustainability efforts.

Many SMEs are confronted with the need for twin transformation: strategically aligning with both digitalization and sustainability simultaneously (Christmann et al., 2024). Research emphasizes the importance of the simultaneous integration of both concepts as the potential synergies could enhance different aspects of the economy and society (for a discussion, see Diodato et al., 2023). For firms, this dual trajectory requires digital transformation alongside a commitment to green production methodologies, addressing specific environmental and societal considerations. However, challenges such as resource shortages, increased complexity in innovation projects, and potentially more ambitious capital requirements and investments, amplify the urgency in SMEs for adaptation (Smallbone et al., 2012; Denicolai et al., 2021). Additionally, the impact of organizational realignment becomes more pronounced, affecting aspects such as workforce dynamics, upskilling and training, and operational efficiency.

However, within this transformative endeavor lie significant opportunities. Theoretically, through the strategic integration of digital and sustainability initiatives, SMEs can enhance resilience, bolster market positioning, push innovative capability, and cultivate long-term viability, meeting the expectations of environmentally conscientious stakeholders and consumers (Ardito et al., 2021). Since twin transformation is a relatively new challenge for SMEs, not many empirical studies have detailed the strategies and effects, and results are sparse and partially contradictory. Some studies, set up as literature reviews, investigate the patterns in these publications (e.g., Isensee et al., 2020; Philbin et al., 2022; Charfedinne et al., 2023), identifying as stylized facts that (i) digitalization supports environmental sustainability, (ii) no significant relationship exists between environmental sustainability and digitalization, and (iii) there is no significant or specific sequence of the two transformations.

Studies have also explored the impact of different digitalization aspects on sustainability. Ghobakhloo et al. (2021) investigate how IoT fosters sustainable innovation across integrated corporate functions. IoT facilitates intraorganizational and intrafirm sustainable innovation through cultural and structural openness, promoting cross functional collaboration and learning. Additionally, it enhances the knowledge base and manufacturing competency, supporting green process innovation capacity and eco-friendly product development economically and competitively. He et al. (2024) empirically show that digital transformation influences green innovation by bolstering firm resources and knowledge capabilities, specifically showing a positive effect on green substantive innovations. Gambardella et al. (2021) explore the role of enabling technologies across diverse domains and discuss public policy implications, considering that innovators may capture smaller shares of benefits from enabling technologies compared to discrete and specific ones, including sustainability innovations.

This is supported by Ghobakhloo (2020), who systematically identifies IoT's sustainability functions, highlighting economic sustainability, production efficiency, and business model innovation as immediate outcomes. Ranta et al. (2021) adopt a case study approach to explore circular economy business models empowered by digital technologies—knowledge generation helps in enhancing resource flows and value creation across diverse industries. They introduce a model delineating four key types of business model innovation for the circular economy, elucidating both incremental and radical improvements in resource flows and value creation and capture. Gupta et al. (2021) devise a framework integrating circular economy, sustainable cleaner production, and IoT standards to evaluate sustainability in manufacturing companies. They underscore the significance of circular economy practices, prioritizing them over cleaner production and IoT initiatives for enhancing sustainability. Finally, Khan et al. (2021) map the key drivers of digitalization playing significant roles in sustainable development, focusing on the triple bottom line (social, environmental, and financial performance), sustainable business models, and the circular economy. The findings reveal a concentration on conceptual analysis in sustainability research, with IoT prominently cited for triple-bottom-line benefits.

Research still lacks insights into the underlying drivers and effects of a strategic orientation towards digitalization and sustainability parallelly. Based on the above discussion, we believe that geographic location (H1), human capital (H2), and innovation activities (H3) are strong enablers for a strategic orientation towards twin transformation as well. We test the following three hypotheses:

H1c SMEs located in urban areas execute more simultaneous efforts towards digitalization and sustainability than SMEs located in rural areas.

H2c Employing graduates has a positive effect on simultaneous efforts towards SMEs’ digitalization and sustainability.

H3c Innovation activities have a positive effect on simultaneous efforts towards SMEs’ digitalization and sustainability.

Fig. 1 combines all proposed relationships into a research model for the empirical study.

MethodologyThis section introduces our dataset, dependent and independent variables, and model specifications. We use cross-sectional data to test the hypotheses and derive the findings, which may initially seem an important limitation in light of our research question. However, as the combined analysis of digitalization and sustainability is a relatively new focus, it was difficult to gather longitudinal panel data—to our knowledge, such data are currently not available for German firms. We focus on cross-sectional data instead, a combination of surveys of KfW from 2019 to 2021 on German SMEs’ strategies, which provide us with evidence from a very large sample. However, both digitalization and sustainability questions were introduced into the questionnaire only in 2021. Nevertheless, we consider this research an important foundation as it explores the current situation and empirically tests the concepts in this research stream from a holistic viewpoint. However, future research will benefit from using longitudinal panel data, allowing for a more detailed view.

Data collection and sampleThis study uses the dataset of the KfW SME panel, a representative survey of German SMEs conducted by the KfW Bankengruppe every year. It is a longitudinal dataset covering SMEs of all sizes and across all industries in Germany, providing a valuable source for information on the economic and structural development of this sector. We focus on German SMEs to get valuable insights into innovation management from an established advanced economy such as Germany, also a leader in innovation spending EUR 190.7 billion on new product, services and processes (Rammer et al., 2024), with 1.5 million firms regularly introducing innovations into the market (Zimmermann, 2024).

SMEs play a crucial role in the German economy, contributing significantly to employment, innovation, and economic growth. According to EU Recommendation 2003/361, an enterprise is classified as an SME if it employs no more than 249 individuals and generates an annual turnover of up to EUR 50 million or has a balance sheet total not exceeding EUR 43 million. Based on statistics from IfM Bonn using the EU classification, as of 2021, approximately 99.3 % of all firms in Germany are SMEs, with total revenues of EUR 2.439,26 million (31.3 % revenue share in the total for all German firms), employing 18.97 million people (54.1 % of all employees in Germany), and spending EUR 8.4 billion (8.2 % of all firms in Germany) on R&D (Institut für Mittelstandsforschung Bonn, 2024). Generally, the KfW SME panel contains a set of quantitative questions on companies’ performance, investment activity, financing structure, and innovation and digitalization activity each year. We focus on the 2022 survey wave (reference year 2021), as it offered information on different sustainability topics for the first time. The survey is based on the concepts and definitions of the Oslo Manual (OECD, 2018). For the analysis, following the EU recommendation, the dataset was restricted to include only SMEs with up to 250 employees. The final sample comprises 7531 firms.

VariablesDependent variablesTo create the dependent variables, the firms in the dataset were divided into four groups based on their strategic orientation: firms that execute (a) sustainability only, (b) digitalization only, (c) both digitalization and sustainability, and (d) neither. Digitalization is a dummy variable taking the value of one if a firm declared to have completed any digitalization project in the firm between 2019 and 2021, and zero otherwise. Digitalization projects refer to activities and measures to renew the IT structure or to use new digital applications, digitize products (including services), contact with customers and suppliers as well as measures to build up knowledge, reorganize the workflow in connection with digitization, or develop and introduce new digital marketing/sales concepts. Similarly, sustainability is a dummy variable taking the value of one if the firm declared to have made climate protection investments in Germany in 2021, and zero otherwise. Climate protection investments refer to investments in measures to avoid or reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the firm. These include investments to save energy or increase energy efficiency, measures to utilize renewable energies or investments in climate-friendly transport, such as the purchase of electric vehicles. Last, the variable Digitalization & Sustainability is a dummy variable taking the value of one if a firm engages in both digitalization projects and climate protection investments, and zero otherwise.

Independent variablesThe geographic density of a firm, representing the geographic location, is determined on the basis of four settlement structure district types provided by the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR, 2024). Large cities are independent cities with at least 100,000 inhabitants. Urban areas are a) districts with a population share in large and medium-sized cities of at least 50 % and a population density of at least 150 inhabitants/km², and b) districts with a population density without large and medium-sized cities of at least 150 inhabitants/km². Rural areas are a) districts with a population share in large and medium-sized cities of at least 50 %, but a population density of <150 inhabitants/km², and b) districts with a population share in large and medium-sized cities of <50 % and a population density excluding large and medium-sized cities of at least 100 inhabitants/km². Finally, sparsely-populated areas are districts with a population share in large and medium-sized cities below 50 % and population density excluding large and medium-sized cities below 100 inhabitants/km².

Graduates within the firm, representing human capital, is measured by the percentage of full-time employees, as of December 31, 2021, who are graduates from a university, a university of cooperative education, or of applied science. Respondents self-reported a percentage number or had the option to choose none, that is, 0 percent. Based on this, we define a dummy variable taking the value of one, if the company employed any graduates and zero, if not.

The firm’s innovation activity is included as a dummy variable taking the value of one if the firm declared to have introduced new products or services (at least one) in the three years before the study. Product innovations cover new or improved physical products (including software, digital products) or services (including digital services). Process innovations comprise new or improved (i) production processes, processes for the provision of services or logistical processes, (ii) information processing methods, supporting methods for administration or management, and (iii) methods for organizing business processes, work organization, and marketing.

Control variablesTo improve the reliability of the model, control variables were included. Firm size, measured by the number of full-time employees in 2021, and investments, measured by a dummy variable that takes the value of one if a firm made any investments in 2021, can codetermine the resources available to a firm for digitalization and sustainability strategies (Elsayed, 2006; Del Canto & Gonzalez, 1999). Firm age can have an influence on the strategic orientation as it impacts the growth, experience and improvement of capabilities (Hannan et al., 1998). Industry, where firms are categorized into a manufacturing, construction, wholesale/retail, or services industry, is important as strategic orientations and innovation are susceptible to sectorial influences (Gault, 2018).

Model specificationsThe dependent variables in this study are dichotomous, either taking the value of one, if they belong to the specific group, or taking the value of zero, if they do not belong. For such binary outcomes, the use of ordinary least squares (OLS) is generally discouraged because the linear probability model can yield predicted probabilities outside the [0,1] range, assumes homoscedasticity, and does not account for nonlinearity, although it remains computationally simple and coefficients are directly interpretable. By contrast, probit and logit models are specifically designed for dichotomous outcomes, leading to superior results than OLS regressions in this case (Hoetker, 2007). They constrain predicted probabilities to [0,1], allow for nonlinear relationships, and have strong theoretical foundations in latent variable modeling (probit) or odds-based interpretation (logit). Probit assumes normally distributed errors, which is advantageous for modeling latent constructs and yields slightly thinner tails than the logistic distribution. However, the coefficients are expressed in z-score units, which are less intuitive to interpret than logit coefficients are. Logit offers coefficients interpretable as odds ratios and is more robust to extreme values. However, when the normal distribution assumption is correct, probit may offer marginally better fit and efficiency.

To compare and choose the model with the best fit, the Akaike Information Criterion and Bayesian Information Criterion were calculated (Jose et al., 2020). The results were very similar, providing mostly minimal lower values of both criteria for the probit model. We follow the literature from fields similar to our research (e.g., Ardito et al., 2021) and use probit maximum likelihood regression models with robust standard errors to analyze the data. To establish validity, the analysis was performed with logistic regression models, rendering the same results (Hahn & Soyer, 2005). Given the marginally better fit, only the probit analysis is reported. All models were set up identically, analyzing the same set of independent variables for all dependent variables.

Empirical resultsTable 1 presents the list of variables included in the models of this study and their descriptive statistics. Table 2 provides an overview on the frequencies.

Variables description and summary statistics.

Frequencies.

Table 3 shows the pairwise correlations, indicating that no multicollinearity concerns exist as none of the independent variables are highly correlated (Cohen et al., 2013). Additionally, the variance inflation factors of all constructs were well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5 (Kock, 2015), further suggesting that the latent variables are independent.

Pairwise correlations.

Note: * = p < 0.05; Manufacturing - Industry base level omitted.

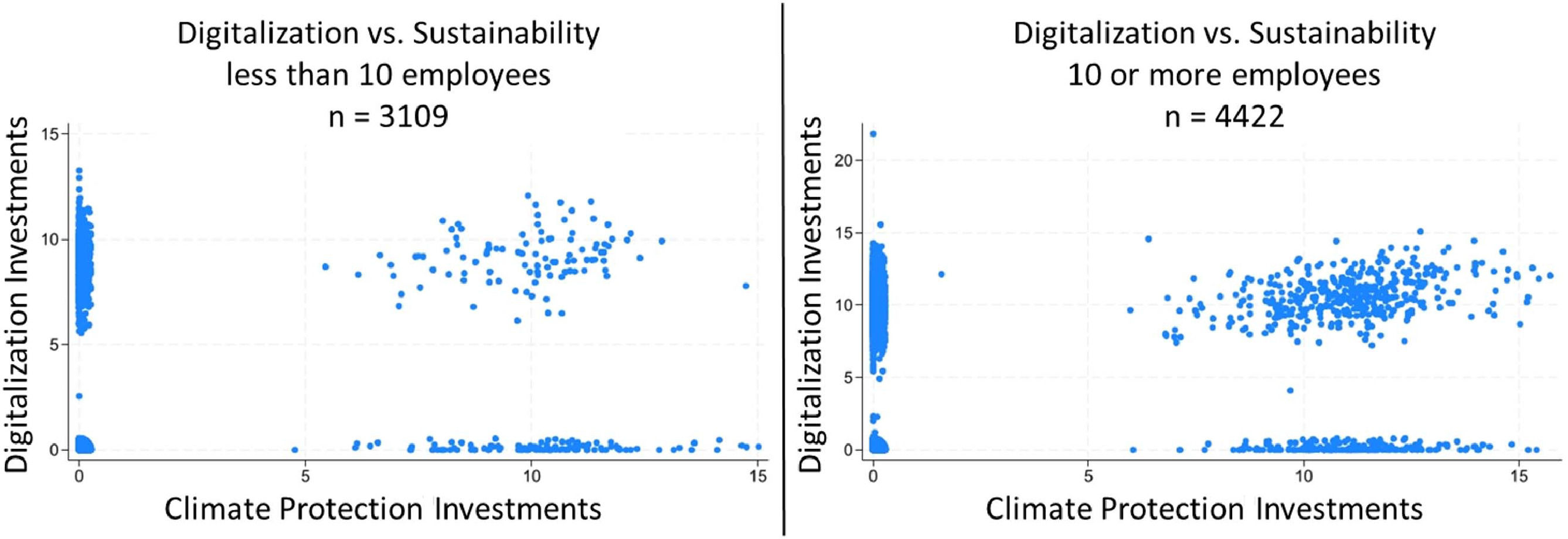

Figs. 2–4 provide a further overview of the data distribution, focusing on firms’ digitalization and sustainability investments. Fig. 2 includes all firms; Fig. 3a and 3b differentiate between firm size (small firms: 0–9 employees; medium firms: 10–249 employees); and Fig. 4a–d distinguish between the geographic density of the firms’ location (large city; urban; rural; sparsely populated).

Table 4a reports the results of the probit model with digitalization as the dependent variable. Model 1a includes only control variables and uncovers that firm size (ß = 0.002, p < 0.01) and investments (ß = 0.404, p < 0.01) have a strongly significant, positive effect on digitalization efforts. For the construction industry (ß = −0.097, p < 0.05) a significantly negative effect is found, whereas for retail/wholesale (ß = 0.136, p < 0.01) and firms in the service sector (ß = 0.153, p < 0.01), the effect is strongly significant and positive. The effect of firm age is not significant, but seems negative (ß = −0.001, p > 0.1). Model 2a includes geographic density and shows a highly significant negative effect (ß = −0.078, p < 0.01). This finding supports H1a, as firms located in urban areas seem to perform more digitalization than firms in less populated areas. Model 3a includes graduates within a firm and reveals a highly significant, positive relationship with digitalization (ß = 0.263, p < 0.01), supporting H2a. Model 4a, which includes innovation activities, shows a highly significant and positive coefficient estimation in favor of digitalization (ß = 0.812, p < 0.01), supporting H3a. Model 5a, the full model, corroborates the previous findings, supporting all hypotheses. However, including all variables changes the effect of firm size on digital orientation, rendering it insignificant.

Probit results (Digitalization effort only, with robust s.e.).

Note: * = p < .1; ** = p < .05; *** = p < .01; Manufacturing - Industry base level omitted.

Table 4b reports the results of the probit model with sustainability as the dependent variable. Model 1b includes only control variables and reveals that both firm size (ß = −0.002. p < 0.01) and firms from the service industry (ß = −0.103, p < 0.05) show a significant negative influence on sustainability effort. Firm age has a highly significant, positive effect (ß = 0.001, p < 0.01) and firms from the construction sector show a marginally significant, positive effect (ß = 0.104, p < 0.1). Firms from the retail/wholesale industry (ß = −0.071, p > 0.1) as well as investments (ß = −0.048, p > 0.1) seem to have a negative influence on sustainability, but the effect is insignificant. Model 2b includes geographic density and shows a highly significant positive effect (ß = 0.050, p < 0.01), rejecting H1b. The less densely the region where the firm is located is populated, the more the sustainability efforts seem to be. Model 3b includes the graduates and rejects H2b, revealing a highly significant, negative relationship (ß = −0.190, p < 0.01). Further, Model 4b, which includes innovation activities, reveals a highly significant negative relationship (ß = −0.463, p < 0.01), rejecting H3b. Model 5b only partially supports previous results as geographic density becomes insignificant as soon as all variables are included. Conversely, investments become significant and show a positive relationship with sustainability efforts (ß = 0.076, p < 0.1).

Probit results (Sustainability effort only, with robust s.e.).

Note: * = p < .1; ** = p < .05; *** = p < .01; Manufacturing - Industry base level omitted.

Table 4c reports the results of the probit model with digitalization&sustainability as the dependent variable. Model 1c includes only control variables and reveals that firm size (ß = 0.004, p < 0.01), investments (ß = 0.596, p < 0.01), and firm age (ß = 0.002, p < 0.01) are positively related to the combined efforts of digitalization and sustainability. Construction firms (ß = −0.158, p < 0.01) have a significantly negative effect, whereas all other industries show insignificant results. Model 2c includes geographic density (ß = 0.003, p > 0.1), showing a positive but insignificant effect, rejecting H1c. Model 3c includes graduates within the firm and reveals a highly significant, positive effect (ß = 0.182, p < 0.01), supporting H2c. Model 4c, which includes innovation activities, shows a highly significant, positive effect (ß = 0.553, p < 0.01), supporting H3c. Model 5c, the full model, confirms the previous findings; however, it alters the effect of geographic density, rendering it marginally significant (ß = 0.035, p < 0.1) and showing a weaker, but still significant effect, for graduates (ß = 0.081, p < 0.1).

Probit results (digitalization & sustainability efforts, with robust s.e.).

Note: * = p < 0.1, ⁎⁎ = p < 0.05, ⁎⁎⁎ = p < 0.01; Manufacturing - Industry base level omitted.

Taking these models together, we observe different patterns with respect to the strategic orientation of a firm and identify three distinct groups: (1) firms solely prioritizing digitalization, which benefit primarily from size (in terms of number of employees and investments) and are located in cities with access to a large number of graduates; (2) those emphasizing sustainability, typically smaller in scale with limited access to graduates and a tendency to be located in less densely populated areas; and (3) firms engaging in twin transformation, exhibiting similar characteristics to those focused on digitalization but possessing more experience and are often older. Furthermore, construction firms prioritize sustainability efforts over digitalization, whereas the opposite effect is observed for firms in the retail/wholesale and services sector. However, the industry-specific factors seem to be dominated when the geographic density, graduates, and innovation activities are taken into account.

While the probit regression results and accompanying graphical analyses provide clear evidence of the direction and statistical significance of the relationships between the dependent and independent variables, we recognize that complementary techniques, such as computing marginal effects or modelling interaction terms, could further enrich their interpretation by translating coefficients into more intuitive probability changes and uncovering conditional dynamics. These extensions would enable a more granular understanding of how each predictor influences the likelihood of firms engaging in digitalization and sustainability activities. Given the scope and constraints of the present study, we intentionally focus on establishing robust baseline estimates and visual patterns, keeping the scope analytically tractable and the results transparent. We view the application of such additional techniques as a logical next step for future research building on our findings, particularly for studies aiming to quantify effect magnitudes in greater detail or to explore heterogeneity across firm types and contexts.

Regarding the relatively low Pseudo R² values across all models, this is common in binary outcome models such as probit and logit regressions, especially when analyzing complex phenomena with multiple unobserved factors influencing the outcome. Unlike the traditional R² in OLS regression, Pseudo R² metrics, such as McFadden’s R² reported here, do not measure explained variance in the same way but rather provide a relative indication of model fit (Veall & Zimmermann, 1994). Moreover, the large sample size employed in this study increases statistical power, enabling the detection of statistically significant effects even when the overall model fit, as indicated by Pseudo R², is modest. The low Pseudo R² values are typical for cross-sectional logit and probit models, and should be interpreted as reflecting the inherent complexity and partial observability of firm-level strategic decision-making, rather than a deficiency in model specification.

DiscussionThis study aimed to explore the influence of a firms' resources and capabilities on the strategic orientation towards SME digitalization and sustainability. By building on resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theories, factors such as the influence of the geographic density of firms’ location, employment of graduates, and innovation activities, all exemplifying knowledge-building opportunities within the firm, were analyzed. Utilizing the KfW SME panel, a representative cross-sectional dataset covering all SMEs in Germany, this study shows that currently not all firms pursue a twin transformation towards digitalization and sustainability, instead some put their efforts in either one or the other. Due to their limited resources and capabilities, SMEs are forced to decide on their focus and adapt their strategic orientation accordingly. While Ardito et al. (2021) analyze product and process performance outcomes, based on the strategic orientation towards digitalization and sustainability, we focused on the general business conditions.

Our results indicate that resource‐ and capability‐related factors—that is, regional knowledge density, graduate employment, and innovation activity—are tightly linked to a digital strategic orientation among German SMEs, but are not systematically associated with a sustainability orientation. This pattern is consistent with our theoretical framing: digitalization is primarily opportunity-driven and depends on absorptive capacity and recombination skills embedded in local knowledge ecosystems and higher-skilled labor, whereas sustainability orientation among SMEs is more often compliance-driven and finance-constrained, such that firms can meet the regulatory thresholds by purchasing mature, off-the-shelf solutions with limited internal capability buildup. The finding that relatively few SMEs pursue a simultaneous twin orientation further suggests that capability bottlenecks and managerial attention constraints force such prioritization. Sectoral heterogeneity, with construction firms skewing toward sustainability and retail/services toward digitalization, is apparent, in line with the differences in regulatory pressure and technology intensity across industries.

Situating these results in the emerging twin-transformation literature (see Christmann et al., 2024), our evidence supports the view that complementarities between digital and green transformations are potential rather than automatic. Conceptual work characterizes twin transformation as a value-adding, bidirectional interplay: digital enables sustainability, sustainability guides digital, and both are implemented through dynamic capabilities that integrate the two logics at “eye level.” However, these capabilities take time and intentionality to build, which helps explain why many SMEs in our sample specialize in a single, instead of twin transformation.

Recent frameworks, as provided by Breiter et al. (2024), go further by mapping capability maturity and pathways. Organizations can climb toward twin maturity from three starting points: “DT experts make DT sustainable,” “ST experts make ST digital,” or “newcomers integrate from scratch.” Each path requires coordinated development across multiple capability dimensions (e.g., technology, products/services, governance, ecosystem). Our cross-sectional analysis reveals that German SMEs with greater experience and age are more likely to adopt twin transformation, consistent with the idea that maturity, slack, and routinized governance help firms orchestrate these interdependent capability investments.

At a broader level, firm and industry studies document links between digital adoption and environmental practices and define twin transitions as mutually reinforcing processes (Siedschlag et al., 2024). However, they also emphasize alignment challenges inside firms. This aligns with our findings on knowledge-based predictors on sustainability. Organizational frictions, financing constraints, and regulation-first adoption might decouple “green” investment from local knowledge access in the short run, especially for SMEs.

Importantly, digitization is not unambiguously green. Case study evidence highlights rebound effects, and the energy intensity of AI and data centers and EU/German rules now push for greener IT (e.g., efficiency benchmarks, renewable power sourcing). These developments make the quality of digitalization (energy-efficient architectures, green cloud, metered emissions) a first-order variable in realizing twin complementarities, again suggesting that twin payoffs depend on specific capability choices, not on going digital per se (Rosenthal & Carreira, 2025; Wilkens & Hinsen, 2024).

Finally, the study setting matters. Germany offers an EU-consistent regulatory environment (CSRD/ESRS, sectoral decarbonization pressures) and a rich SME base. Recent European practice-oriented studies similarly argue that synergy is unlocked when firms treat digital and sustainability as a firm-wide transformation with shared governance levers (with IT and finance as catalysts) and portfolio-level roadmaps. Our evidence complements these insights by showing where synergies are not yet realized among SMEs and by pointing to concrete capability gaps (Bitzer, 2023).

Together, the results detail what we consider prevailing narratives: (i) capability endowments that matter for digitalization do not automatically trigger sustainability strategies in SMEs; (ii) twin transformation requires coordinated, staged capability development that many SMEs have not yet undertaken; and (iii) industry structure and regulatory salience shape which side of the twin firms prioritize.

Managerial implicationsFrom a managerial perspective, our findings provide the following implications. First, given resource constraints, managers should explicitly select one of the three empirically grounded pathways: make DT sustainable, make ST digital or integrate from scratch, and stage investments accordingly. For DT-first firms, prioritize “green-by-design” digital (efficient data pipelines, green cloud, metered compute) and attach sustainability objectives and KPIs to digital programs. For ST-first firms, instrument sustainability initiatives with data platforms to lower measurement and compliance costs and open new digital service models. Using maturity diagnostics to identify gaps across technology, products/services, governance, people/skills, and ecosystems would help (see Breiter et al., 2024).

Second, firms should build dynamic capabilities, not only projects. Twin outcomes hinge on cross-functional routines, such as, environment scanning, portfolio reprioritization, and transformation governance, that integrate digital and sustainability. Therefore, (i) install joint digital–sustainability steering with shared objectives; (ii) embed carbon and circularity metrics into product and process dashboards; and (iii) align capital budgeting so that digital business cases internalize energy and emissions. These measures operationalize the “capabilities body and wings” logic emphasized in the capability frameworks (Christmann et al., 2024).

Third, exploiting near-term synergies with proven use cases is necessary. SMEs should focus on high-leverage bundles: process mining plus energy metering for shop-floor optimization; predictive maintenance to reduce material/energy waste; demand forecasting to cut overproduction; traceability to meet CSRD/EUDR. Evidence from case studies shows that such bundles deliver faster ROI and accelerate capability learning when framed as a single transformation program (e.g., Rosenthal & Carreira, 2025; Bitzer et al., 2023).

Forth, green the digital core early. Because AI and data infrastructure can raise energy demand, SMEs should adopt efficiency guardrails as they scale analytics/AI—migrate to energy-efficient cloud, monitor PUE/renewable coverage, right-size models, and favor scheduling that co-optimizes cost and carbon. New EU and German regulations (e.g., energy-efficiency obligations for data centers or rising renewability/circularity requirements) are guardrails for both risk management and cost control.

Fifth, firms need to sequence twin transformation to the industry context. In construction, prioritize sustainability compliance and operational abatement (materials, site logistics) and then digitalize measurement and reporting. In retail/services, lead with data-driven digitalization (customer analytics, omnichannel) while embedding green IT standards. This sector-contingent sequencing reconciles our heterogeneity findings with the general complementarity claims in the literature (e.g., Tabares, 2025).

Finally, measuring what matters and communicating credibly is crucial. Firms should align disclosure (CSRD/ESRS) with operational data streams to reduce reporting burdens and to surface efficiency opportunities. Twin-related KPIs should be treated as components of the firm’s strategy narrative to investors and employees. The European practice literature emphasizes the role of finance and IT as catalysts for this integration (Bitzer et al., 2023).

These implications are actionable for resource-constrained SMEs because they emphasize path-dependent choice, capability sequencing and synergetic use cases, not simply transformation all at once. The managerial task is to take digital and sustainability efforts from competing “projects” into a unified capability system compounding over time.

Limitations and future research directionsThis study has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, our analysis only considers input factors that impact SME efforts towards sustainability or digitalization. No output measures, such as performance, growth or profitability were considered, and hence, no inferences about the effects of different strategic orientations could be made. Future research building on this study should additionally consider the outcomes of different efforts to provide further insights. Financial performance would be of special interest, as strategic orientations are always tied to investment decisions. Linking strategic choices to financial outcomes could help to assess whether sustainability- or digitalization-driven initiatives translate into measurable performance advantages. Durana et al. (2025) highlight the relevance of financial prediction models, emphasizing how contextual and structural factors shape financial wellbeing of SMEs across the Bucharest Nine countries. Integrating such financial modeling approaches may enable future studies to more comprehensively capture the interplay between strategic orientations, framework conditions, and economic results. In this way, subsequent research could bridge the gap between input-oriented analysis and the financial implications of strategic orientation. Furthermore, the dependent variables we use are binary, perhaps not adequately capturing the complete scope of the measures. The results should be confirmed with a richer measure for digitalization and sustainability, including the various aspects of both strategic orientations (e.g., different areas of sustainability and digitization efforts and their degree).

Second, the present study focuses on German SMEs, gathering insights from a well-established economy with a strong focus on technology and specific sustainability regulations. Replications of the analyses in other countries, especially in less developed regions, and performing cross-country comparisons would be interesting, to further investigate and acquire a more profound understanding of firm strategic orientations towards sustainability and digitalization. Our approach is readily repeatable in other EU contexts because the underlying variables—digitalization, sustainability investment, innovation activity, and firm capabilities—are also consistently available in comparable structure in harmonized surveys such as the EIB Investment Survey (EIBIS) by the European Investment Bank and the Community Innovation Survey (CIS) by Eurostat. These datasets should support estimations across EU-27 firms to create additional validity beyond Germany. Future EU-wide replications could test sequencing and policy heterogeneity using EIBIS panels and CIS innovation items. In summary, the design can be replicated and expanded across EU countries with comparable data and methods, offering a robust framework for cross-national analysis of twin strategic orientations. Similarly, our data did not allow for a regional differentiation within Germany. To gain deeper insights, further analyses on a federal-state level should be conducted. Third, the data only allowed for limited insights into the interplay of digitalization and sustainability, namely the different aspects of a twin (or dual) transformation.

The literature provides mixed evidence on whether firms approach and address digitalization and sustainability sequentially, in parallel, or leverage one as an enabler for the other. Since these effects could be time-dependent, future research should build on the findings and further analyze SME strategies for twin transformation utilizing longitudinal data. In particular, a time series analysis that captures SME dynamism regarding digitalization and sustainability, and tracks sequencing (digital-first vs. green-first) as well as corresponding capability accumulation, is necessary.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNika Hein: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Markus Thomas Münter: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Conceptualization. Volker Zimmermann: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation.

The authors would like to thank the seminar participants at Université de Strasbourg and Universität Witten/Herdecke as well as Marcus Dejardin and Markus Hertrich for the helpful comments on earlier drafts of the paper.