As digital technologies reshape the global economy, fostering digital entrepreneurial intention (DEI) among university students has become an urgent educational goal. However, empirical research on how entrepreneurship education promotes DEI, particularly through creativity and digital literacy, remains limited. Drawing on survey data from 1188 graduating students at a “double first-class” university in Guangdong, China, this study examines how different forms of entrepreneurship education (theoretical vs. practice-based) influence DEI. To control for selection bias and strengthen causal inference, propensity score matching (PSM) is applied. The results show that practice-oriented education significantly enhances DEI by fostering creativity, which serves as a mediating mechanism. Moreover, digital literacy, particularly growth-oriented social media use, moderates the direct effect of education on DEI, amplifying its impact, while entertainment-oriented use diminishes it. These findings underscore the importance of experiential entrepreneurship curricula that integrate digital skill development and purposeful social media engagement to cultivate entrepreneurial readiness in the digital age.

The global wave of digital transformation, driven by artificial intelligence and emerging technologies, has profoundly reshaped the entrepreneurship landscape. Digital entrepreneurship, which harnesses these technologies to create and deliver value, has become a vital driver of economic growth and industrial renewal. As digital platforms lower traditional barriers to entry, they create new opportunities for young entrepreneurs, especially in emerging markets. Research shows that digital entrepreneurship not only contributes to economic growth but also helps address youth unemployment in developing economies (Aloulou et al., 2024). In China, this trend is particularly evident among university students who are facing increasing employment pressure. According to the 2021 Report on College Students’ Entrepreneurship in China, the internet and IT-related sectors are now the most popular entrepreneurial choices among students, reflecting the transformative influence of digital technologies on career pathways.

As China accelerates its national digital transformation strategy—“Digital China”—igital Chinalerates its national digital transformation nologies skills and mindset needed for success in a digitally driven economy. According to the recent Graduate Employment and Entrepreneurship Report, 20.84% of 2023 graduates expressed interest in pursuing careers or starting ventures in the digital economy. This rising interest underscores the strategic relevance of digital entrepreneurship to national development. However, successful participation in digital entrepreneurship requires more than technological access; it demands core digital competencies. These include applying emerging tools, managing digital risks, and evaluating relevant information streams (Soltanifar et al., 2021). However, many students lack systematic preparation in these areas.

Against this backdrop, digital entrepreneurial intention (DEI), which is students’ intentions to initiate digitally enabled ventures, has emerged as a critical construct for understanding youth innovation in the digital era. While entrepreneurial intention has been widely studied, considerably less attention has been given to DEI, which demands a unique blend of creativity, digital literacy, and opportunity recognition. Although entrepreneurship education is known to shape entrepreneurial intention (Bae et al., 2014; Xu & Song, 2024), its role in specifically fostering DEI has received limited empirical attention.

At the same time, several critical research gaps remain unaddressed. First, existing studies rarely disentangle different components of entrepreneurship education, such as theoretical instruction versus practice-based formats, and their distinct effects on DEI. Second, the role of creativity as a mediating process in the formation of DEI, especially in digital contexts, has received insufficient empirical attention. Third, digital literacy is often regarded as a fixed personal trait rather than as an interactive condition that can moderate the impact of education.

To address these gaps, this study proposes an integrated framework to examine how entrepreneurship education, creativity, and digital literacy jointly influence DEI among university students in China. The following research questions guide the investigation:

RQ1 To what extent does entrepreneurship education influence university students’ DEI?

RQ2 Does creativity mediate the relationship between entrepreneurship education and DEI?

RQ3 Does digital literacy moderate the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in shaping students’ DEI?

Drawing on survey data from 1188 graduating students at a “double first-class” university in Guangdong, China, this study examines how both theoretical and practice-based forms of entrepreneurship education influence students’ DEI outcomes. Additionally, it analyzes the moderating roles of digital competence and social media use, and the mediating role of creativity. To enhance causal inference and control for selection bias, propensity score matching (PSM) is applied, comparing students with and without entrepreneurship education based on observed covariates. The findings are expected to offer valuable insights for universities, policymakers, and educators aiming to improve entrepreneurship education frameworks in the digital era.

In doing so, this study makes several important contributions to the literature on digital entrepreneurship and education.

First, it provides empirical evidence on how creativity and digital literacy jointly shape DEI among university students. While prior studies have examined these constructs separately, this study integrates them into a unified framework grounded in the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and social cognitive career theory (SCCT), offering new theoretical insights.

Second, by distinguishing between theoretical and practical modes of entrepreneurship education, the study reveals that practice-oriented formats, such as competitions and hands-on projects, exert a significantly more substantial influence. This contributes to the growing body of research aimed at enhancing the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in digital environments.

Third, by focusing on Chinese university students, the research applies PSM to isolate better the effects of entrepreneurship education and control for selection bias, addressing a significant methodological gap in prior studies.

Lastly, it advances the literature on digital entrepreneurial ecosystems by examining how social media use types, classified as growth-oriented vs. entertainment-oriented, moderate the educational pathway to digital entrepreneurship. This aligns with recent calls (Sahut et al., 2021; Elia et al., 2020) for universities to serve not only as providers of knowledge but also as ecosystem builders, fostering entrepreneurial readiness through networks, digital tools, and experiential learning opportunities.

The remainder of the manuscript is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature on digital entrepreneurship, entrepreneurship education, creativity, and digital literacy, followed by the development of research hypotheses. Section 3 outlines the research design, including data sources, variable operationalization, and the application of PSM for causal inference. Section 4 reports the empirical findings and robustness checks. Section 5 provides a detailed discussion of the theoretical and practical implications, along with the study’s limitations. Finally, Section 6 presents the concluding remarks and outlines directions for future research.

Literature reviewConceptual definitions and clarificationsEntrepreneurship and digital entrepreneurshipThe rapid proliferation of digital technologies and the rise of platform-based economies have profoundly transformed the entrepreneurial landscape, leading to the emergence of digital entrepreneurship. This form of entrepreneurship is distinct from traditional models in that it relies heavily on the use of digital platforms, online tools, and emerging media technologies to identify, exploit, and scale business opportunities (Bican & Brem, 2020; Sahut et al., 2021).

Digital entrepreneurship encompasses a broad spectrum of activities. These include e-commerce, app development, social media influencing, livestream commerce, and virtual service delivery (Delacroix et al., 2019; Törhönen et al., 2021). Its relatively low capital requirements and broad accessibility allow individuals, particularly students and digital natives, to participate in entrepreneurial activity with fewer resource constraints (Xin & Ma, 2023).

Over time, scholarly definitions of digital entrepreneurship have evolved. Initially, these definitions were primarily centered on technological aspects. For instance, Kollmann & Kuckertz (2006) characterized digital entrepreneurship as the creation of digital goods and services distributed via electronic networks. Later, Nambisan (2017) emphasized the dynamic, innovation-driven nature of digital entrepreneurship, where digital tools shape not only product offerings but also organizational forms and stakeholder interactions. More recently, researchers have examined digital entrepreneurship as a systemic and process-oriented phenomenon, encompassing opportunity recognition, value creation, and venture scaling, all facilitated by digital affordances (Sahut et al., 2021; Kraus et al., 2019).

In line with this progression, the present study defines digital entrepreneurship as the process of identifying and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities through digital technologies, particularly internet-based tools and emerging media, to create and deliver new forms of value (Elnadi & Gheith, 2023). This definition underscores the transformative impact of digitalization in reshaping entrepreneurial logic, from physical to virtual channels, from resource-intensive to lightweight models, and from local to global reach.

Furthermore, the rise of digital entrepreneurship has led to the formation of digital entrepreneurial ecosystems, in which universities serve as key institutional anchors. Universities contribute not only knowledge and infrastructure but also play a central role in shaping students’ entrepreneurial mindsets and digital competencies (Elia et al., 2020). As digital natives, university students are uniquely equipped to harness online environments for entrepreneurial learning and action (Teo, 2016).

Nevertheless, despite growing interest in student entrepreneurship, limited research has systematically examined the mechanisms through which entrepreneurship education fosters DEI. Further, the enabling conditions, such as digital literacy and social media engagement, which shape students’ capacity to engage in digital entrepreneurship, remain underexplored. These gaps underscore the need for a more integrated theoretical account of how cognitive, educational, and contextual factors influence digital entrepreneurship.

Entrepreneurial intention and digital entrepreneurial intentionEntrepreneurial intention refers to an individual’s deliberate commitment and psychological preparedness to start a new business. It is widely regarded as a reliable predictor of actual entrepreneurial behavior (Bae et al., 2014). This construct captures not only motivation but also an individual’s planning orientation and perceived feasibility in launching entrepreneurial ventures (Thompson, 2009). Grounded in cognitive models of planned behavior, entrepreneurial intention reflects the mental process through which individuals develop the desire and formulate strategies to become entrepreneurs.

In the context of the digital economy, traditional entrepreneurial intention has evolved to encompass the use of digital technologies and platforms. DEI extends the core notion of entrepreneurial intention by focusing on how individuals leverage internet-based tools, social media, and digital infrastructures to identify opportunities, design scalable business models, and implement them in online environments (Dutot & Van Horne, 2015; Aloulou et al., 2024). Therefore, DEI captures not only whether an individual intends to start a business, but also whether they intend to do so through digital means.

Mugiono et al. (2021) introduced the notion of “online entrepreneurial intention,” underscoring the role of sustained digital engagement, such as online information search, planning behavior, and platform participation, in supporting entrepreneurial ambition. This aligns with broader definitions of DEI, which emphasize an individual’s capacity and readiness to utilize digital tools for business innovation and value creation (Abaddi, 2024). Importantly, DEI also demonstrates adaptability to rapidly evolving digital environments and the capacity to navigate technological opportunities and constraints.

As digital platforms and tools become increasingly embedded in entrepreneurial processes, understanding DEI becomes essential, particularly for digital-native student populations. It offers a valuable lens to assess how educational programs, cognitive factors such as creativity, and enabling conditions like digital literacy and social media behavior jointly influence students’ entrepreneurial aspirations in digital contexts.

Entrepreneurship education and its evolutionEntrepreneurship education refers to a structured process through which individuals, particularly students, develop entrepreneurial awareness, mindset, and competencies via formal coursework, project-based learning, and hands-on activities (Xiang & Lei, 2014). Traditionally, its core objectives include shaping entrepreneurial cognition (Donckels, 1991) and fostering key capabilities such as opportunity recognition, technological adaptability, and risk tolerance (Li, Bu, Zhang, & Huang, 2024). In today’s digital economy, these goals are increasingly intertwined with the need to prepare students to identify and capitalize on technology-enabled entrepreneurial opportunities (Yami et al., 2021).

Despite its growing relevance, entrepreneurship education continues to face persistent challenges, including outdated curricula, limited university–industry collaboration, and inadequate alignment with the rapidly evolving digital and global business landscape (Ma & Wang, 2023). Traditional programs have often emphasized general business knowledge (Mukesh et al., 2020) while overlooking emerging competencies such as data-driven decision-making and digital platform design (Nowiński et al., 2019). As a result, the field is shifting from a conventional to a digitally integrated paradigm, one that actively incorporates digital tools, platforms, and mindsets into educational design (Ratten & Usmanij, 2021).

This digital shift in entrepreneurship education is evident across three key areas of evolution. First, teaching methods are being reimagined through online platforms, gamification, and blended learning models (Xin & Ma, 2023). Second, the scope of education is expanding to include students from non-business disciplines, emphasizing interdisciplinary and digitally native capabilities (Teo, 2016). Third, experiential learning, via startup incubators, digital simulations, and real-world problem-solving, has become a central pedagogical approach (Henry, 2020).

Through these innovations, education is no longer confined to traditional models of venture creation. Instead, it acts as a catalyst for transforming digital literacy, enhancing creativity, and fostering intention, all of which are critical for navigating the complexities of the digital entrepreneurial landscape (Richter et al., 2017). This conceptual evolution highlights the growing interplay between educational intervention, individual cognition, and the enabling digital environment, an interplay that informs the present study’s analytical model.

Theoretical foundation and research hypothesesIntegrative theoretical frameworkThis study draws on two complementary frameworks—the TPB (Ajzen, 1991) and SCCT (Lent et al., 1994)—to explore the mechanisms linking entrepreneurship education to DEI. These theories have been widely applied to explain entrepreneurial behavior in traditional contexts and provide a strong foundation for understanding intention formation, cognitive mediation, and contextual moderation in the digital age.

According to the TPB, entrepreneurial intention is shaped by three key psychological components: attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Entrepreneurship education can influence these components by reshaping students’ beliefs, equipping them with entrepreneurial knowledge, and enhancing their confidence to act. Within this framework, creativity serves as a cognitive enabler, facilitating students’ capacity to imagine, design, and implement novel entrepreneurial solutions. This aligns with previous studies that emphasize the critical role of creativity in translating education into entrepreneurial outcomes (Shahab et al., 2019).

SCCT emphasizes the interaction of personal agency, learning experiences, and environmental supports in shaping career-related outcomes. Within this framework, digital literacy serves as a boundary condition, affecting how effectively entrepreneurship education is translated into entrepreneurial intention. It enhances students’ capacity to apply acquired knowledge in digital contexts (Yang & Zhou, 2019; Bachmann et al., 2024). By increasing opportunity awareness and reducing implementation barriers, digital literacy enhances the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in fostering students’ intentions to take action.

By integrating these theoretical lenses, this study examines how entrepreneurship education (1) directly influences DEI, (2) operates through creativity as a mediating mechanism, and (3) interacts with digital conditions, specifically digital competence and social media use, to shape entrepreneurial outcomes.

Fig. 1 presents the theoretical framework of this study, which examines the complex mechanisms influencing university students’ DEI and offers both theoretical and empirical foundations for improving the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education in the digital age.

Entrepreneurship education and digital entrepreneurial intentionEntrepreneurship education has long been recognized as a foundational intervention for fostering entrepreneurial intention among university students (Turner & Gianiodis, 2018). Drawing on the TPB, such education can influence intention formation through shaping students’ attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). Acquiring entrepreneurial knowledge and being exposed to entrepreneurial environments enable students to view entrepreneurship as both a desirable and feasible career path, strengthening their intention to pursue it (Alberti et al., 2004; Ye, 2009; Hoang et al., 2020).

In the context of digital transformation, entrepreneurship education has increasingly incorporated digital content, tools, and methods. This digital shift empowers students to identify, evaluate, and exploit entrepreneurial opportunities through digital technologies, strengthening their DEI (Lei & Chen, 2021; Ma & Wang, 2023). This aligns with SCCT’s emphasis on how learning experiences and self-efficacy, especially in technology-mediated environments, can shape goal-directed behaviors (Lent et al., 1994).

Importantly, the structure and content of entrepreneurship education matter. Research has shown that theoretical instruction (e.g., classroom courses) and practical engagement (e.g., startup competitions, business simulations) exert differentiated effects on students’ entrepreneurial mindset and action-readiness (Zhu & Zhang, 2014; Hu, Wang, & Zhang, 2018). Practical formats often foster greater cognitive activation, emotional engagement, and exposure to real-world uncertainty, making them particularly effective in digital contexts (Nowiński et al., 2019; Teo, 2016). A large-scale national survey of 1231 Chinese universities found that students rated practice-based formats (e.g., entrepreneurship competitions) as more influential than purely theoretical courses in enhancing entrepreneurial development (Huang & Huang, 2019).

However, challenges remain. Outdated curricula, a lack of real-world exposure, and insufficient alignment with digital skill demands may limit the transformative impact of entrepreneurship education (Ding, 2007; Mei & Symaco, 2022; Xu & Song, 2024). Educators without entrepreneurial experience may struggle to translate abstract concepts into meaningful entrepreneurial practice (Loi et al., 2022). These gaps underscore the importance of identifying which components of entrepreneurship education are most effective in enhancing entrepreneurial intention within digital contexts.

Based on this literature and the integrated theoretical framework, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1 Entrepreneurship education positively influences university students’ digital entrepreneurial intention.

H1a Theory-oriented entrepreneurship education positively influences digital entrepreneurial intention.

H1b Practice-oriented entrepreneurship education positively influences digital entrepreneurial intention.

Creativity, defined as the ability to produce novel and valuable ideas (Amabile, 2018; Boysen et al., 2020), is widely recognized as a core component of entrepreneurial behavior. It enables individuals to identify opportunities, generate innovative solutions, and adapt to uncertain environments. In entrepreneurship research, creativity has been found to significantly predict entrepreneurial intention, especially when cultivated within structured learning environments(Zampetakis & Moustakis, 2006; Zampetakis et al., 2011).

Entrepreneurship education fosters creativity by promoting divergent thinking, enhancing problem-solving skills, and encouraging experimentation. Through exposure to real-world challenges and interdisciplinary knowledge, students develop both creative self-efficacy and the confidence to act entrepreneurially (Belitski & Desai, 2016). Studies have demonstrated that creativity serves as a key mediating mechanism in this process. For example, Shahab et al. (2019) found that creativity mediates the relationship between entrepreneurial exposure and intention. Similarly, Yar Hamidi et al. (2008) showed that higher creativity scores significantly increased the likelihood of entrepreneurial decision-making.

In the context of digital entrepreneurship, creativity gains renewed significance, not merely as a personal trait, but as a strategic capability that drives innovation amid technological uncertainty. Laguía et al. (2019) redefine creativity in this domain as “a dynamic capability to achieve business innovation using technological resources,” reflecting its critical role in navigating digital environments. Creative individuals are more likely to view digital transformation as an opportunity, develop innovative digital business models, and apply technical tools in original ways (Rodrigues et al., 2019). Moreover, digital entrepreneurship education increasingly relies on project-based learning, such as data-driven product design or platform development, which explicitly connects creativity with digital application (Belitski & Desai, 2016).

These findings align with both the TPB (Ajzen, 1991), which views creativity as a contributor to favorable attitudes and perceived control, and social cognitive theory (SCT; Wood & Bandura, 1989), which emphasizes creativity as a learnable skill reinforced through experiential learning. Therefore, creativity plays a crucial role in mediating the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention.

Based on the above, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2 Creativity mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and digital entrepreneurial intention.

H2a Theory-oriented entrepreneurship education influences digital entrepreneurial intention through creativity.

H2b Practice-oriented entrepreneurship education influences digital entrepreneurial intention through creativity.

Digital literacy has evolved from its original definition, as the ability to locate and organize digital information (Gilster & Pool, 1997) into a more comprehensive construct that encompasses both technical proficiency and critical thinking skills. Contemporary interpretations highlight two major dimensions: (1) digital competence, which is the ability to access, evaluate, and apply digital tools; and (2) social media use, which is the strategic use of interactive platforms for information exchange, collaboration, and entrepreneurial engagement (Yang & Zhou, 2019; Bachmann et al., 2024).

This study conceptualizes digital literacy as a multidimensional construct that empowers individuals to acquire, process, and create knowledge within digital environments. It extends beyond technical proficiency to include cognitive and ethical dimensions such as information filtering, online communication, and responsible platform use. As students engage in increasingly digitalized learning and work contexts, digital literacy becomes a foundational skill set for navigating entrepreneurial opportunities in the digital economy.

Within this broader framework, digital competence serves as a critical enabler, empowering aspiring entrepreneurs to leverage new technologies, manage digital workflows effectively, and identify innovation-driven opportunities (Oggero et al., 2020; Mancha & Shankaranarayanan, 2021). Research has shown that individuals with higher levels of digital competence are more confident, adaptive, and entrepreneurial (Santos et al., 2020; Reis et al., 2021). According to SCT, digital competence enhances self-efficacy and promotes perseverance, which are key attributes in the pursuit of entrepreneurial goals (Wood & Bandura, 1989). However, digital skills alone may not automatically translate into higher intention unless activated through educational stimuli. Therefore, we argue that students with stronger digital competence are better equipped to internalize the benefits of entrepreneurship education, amplifying its impact on DEI.

At the same time, social media has revolutionized the way entrepreneurs generate ideas, test concepts, and market their ventures. Defined as internet-based platforms that enable the creation and exchange of content (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010), social media serves as a space for learning, experimentation, and peer interaction. Entrepreneurs use social media not only for brand visibility but also for business model innovation, customer feedback, and opportunity discovery (Kwon & Wen, 2010; Jacobson et al., 2020). For students, active use of social media can enhance entrepreneurial awareness, provide access to role models, and strengthen perceived behavioral control, an essential determinant in the TPB (Ajzen, 1991). Moreover, social media platforms reduce information asymmetries and help users identify patterns in fast-changing markets, making them valuable complements to formal entrepreneurship education (Gavino et al., 2019; Drummond et al., 2018).

Therefore, both digital competence and social media use are theorized to act as moderating variables, or boundary conditions, that influence the strength of the relationship between entrepreneurship education and DEI. Students with higher levels of digital literacy are likely to benefit more from educational interventions than those with limited digital exposure or skills.

Based on this reasoning, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3 The effect of entrepreneurship education on digital entrepreneurial intention is moderated by digital literacy.

H3a Digital competence moderates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and digital entrepreneurial intention.

H3b Social media use moderates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and digital entrepreneurial intention.

In recent years, China has placed strong emphasis on cultivating entrepreneurial and digital competencies among university students, as reflected in national policy initiatives such as the 2015 State Council’s Guiding Opinions on Deepening Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education Reform in Higher Education Institutions. This policy mandates the integration of innovation and entrepreneurship education into all stages of university curricula to promote practical skills, foster interdisciplinary learning, and support digital transformation. As a result, Chinese college students have become a strategically prioritized group in the national push toward digital entrepreneurship.

Given this context, this study focuses on university students in China as a theoretically and practically significant sample for examining DEI. College students are not only active participants in entrepreneurship education but also among the earliest adopters of digital tools and platforms, making them especially relevant to research in the digital economy.

The empirical data were collected in October 2023 from South China Agricultural University (SCAU), a “double first-class” institution located in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province. Situated in the heart of the Pearl River Delta, one of China’s most economically developed and digitally innovative regions, SCAU provides a representative case for exploring how entrepreneurship education intersects with creativity and digital literacy. The university is located near innovation hubs such as Shenzhen and Hong Kong and has been designated by the Ministry of Education as a model institution for graduate employment.

With over 50,000 students enrolled across 25 academic disciplines, including agriculture, engineering, life sciences, economics, management, humanities, and the arts, SCAU features a multidisciplinary student population that enhances the diversity and generalizability of the findings. Additionally, it is a pilot institution for the national “three alls” educational reform initiative, which promotes holistic student development through integrated faculty engagement, continuous involvement, and interdisciplinary learning.

Participants in this study were recruited using a stratified convenience sampling method, targeting final-year undergraduate and graduate students from a wide range of academic backgrounds, including science, engineering, social sciences, and humanities. The recruitment process was conducted via faculty-managed WeChat groups to ensure broad participation. To encourage honest and complete responses, small monetary incentives (ranging from 1 to 3 CNY) were distributed via WeChat’s “red packet” system. Standard data cleaning procedures were implemented, including logical consistency checks and time threshold filters, to ensure the validity of the responses.

A total of 1262 questionnaires were initially collected. After removing invalid responses, such as those from non-university participants and individuals outside the age range of 14–35 years, the final dataset contained 1188 valid responses, resulting in a high effective response rate of 94.14%. Although the sample is drawn from a single university, its disciplinary and demographic diversity provides a solid foundation for analytical generalization within the broader context of China’s digitally transforming higher education system.

Core variablesDigital entrepreneurial intentionDEI serves as the primary dependent variable in this study and is defined as individuals’ intentions to engage in digital entrepreneurship in the future. Entrepreneurial intention is widely recognized as a key psychological precursor to entrepreneurial behavior (Xu & Song, 2024), and its measurement is often based on individuals’ forward-looking assessments of their entrepreneurial motivation.

Drawing on prior studies (e.g., Thompson, 2009; Jian, Duan, & Zhu, 2010), we used a single-item, 5-point Likert scale to measure this construct: “What is your intention to engage in digital entrepreneurship in the future?” The scale ranges from 1 (“very low”) to 5 (“very strong”). This continuous format captures the nuanced degree of intention more effectively than binary or categorical alternatives. The single-item design was chosen both for its empirical validation in prior research and its practical advantage in minimizing respondent fatigue in large-scale survey contexts.

Entrepreneurship educationEntrepreneurship education is the primary independent variable, operationalized through students’ self-reported participation in educational activities. Building upon Zhu & Zhang (2014), entrepreneurship education is classified into two categories: theory-oriented and practice-oriented. While previous studies have differentiated between institutional-level instructional factors and individual student attitudes (Ning, He, Deng, & Zeng, 2023), this study specifically focuses on the latter by measuring respondents’ participation in various entrepreneurship education activities.

Respondents were asked a multiple-choice question: “Which of the following entrepreneurship-related activities have you participated in?” Options included entrepreneurship courses, competitions, seminars, training programs, simulations, and business plan contests. These were categorized as follows:

- (1)

Theory-oriented education: Includes entrepreneurship courses, seminars, and training programs, which primarily focus on the dissemination of entrepreneurial knowledge.

- (2)

Practice-oriented education: Includes entrepreneurship competitions, simulations, and business plan contests, which emphasize the application of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills.

- (3)

General entrepreneurship education: Participation in any of the above activities.

Binary coding was used to reflect participation (1 = participated; 0 = did not participate). This coding scheme enables us to examine both the overall effect of entrepreneurship education and to compare the distinct influences of theoretical versus practical formats. The resulting binary variables are further incorporated into the PSM procedure, enabling us to construct matched treatment and control groups based on students’ reported participation in various types of entrepreneurship education.

CreativityCreativity functions as a mediating variable in our model, representing the psychological mechanism through which entrepreneurship education may influence DEI.

This construct is measured using a single-item self-assessment, following prior work on self-perceived creativity in entrepreneurship (Gorgievski et al., 2018; Bachmann et al., 2024): “How would you evaluate your creativity?” Responses are recorded on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“very poor”) to 5 (“very good”).

While single-item measures may have limitations regarding construct depth and reliability, they are widely used in entrepreneurship research to efficiently capture core psychological traits, particularly when the construct is clearly defined and respondents can reliably self-assess.

Digital literacyDigital literacy is treated as a moderating variable and is divided into two conceptually related dimensions: digital competence and social media use.

Digital competence refers to individuals’ ability to use digital tools, platforms, and technologies effectively. It is assessed by asking respondents: “How would you rate your digital skills (e.g., proficiency in Office applications, programming, Photoshop, video editing software, online collaboration tools)?” Responses are on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“very poor”) to 5 (“very good”).

Social media use is measured according to participants’ purposes for engaging with social media platforms. Respondents select from the following list: browsing news and current events; interacting with friends and family; joining interest-based groups or forums; learning or developing personal interests and skills; building professional networks or seeking job opportunities; and sharing personal updates or opinions. Each selected purpose is assigned 1 point; the composite index ranges from 0 to 6, reflecting the breadth and engagement level in social media activity. This score captures intentionality in digital interactions rather than mere frequency, providing a more nuanced proxy for functional digital literacy.

Analytical strategyThis study investigates whether entrepreneurship education has a significant impact on creativity and DEI among university students in China. While many Chinese universities, including the one surveyed in this study, have incorporated courses like Fundamentals of Innovation and Entrepreneurship and Entrepreneurship Practice into their curricula, students’ experiences with such education vary widely due to differences in instructional quality, engagement, and perceived value. As a result, students’ likelihood of receiving meaningful entrepreneurship education is systematically linked to their background characteristics, which introduces the potential for selection bias.

To address this challenge and enhance causal inference, we employ PSM, a quasi-experimental technique that constructs statistically equivalent treatment and control groups based on observed covariates. Compared to traditional regression-based approaches, PSM is advantageous in non-randomized settings because it reduces confounding by balancing covariates between groups before outcome analysis.

PSM procedureMatching is conducted on a range of theoretically relevant covariates, including gender, academic discipline, education level, only-child status, family upbringing environment, household economic condition, and the highest parental educational attainment (see Table 1 for details).

Description of covariates.

Following the classification framework proposed by Beecher & Trowler (2008), academic disciplines were categorized into four types: applied soft disciplines (e.g., economics, law, management, education, and military science), applied hard disciplines (e.g., engineering, agriculture, and medicine), pure soft disciplines (e.g., philosophy, literature, history, and the arts), and pure hard disciplines (e.g., natural sciences).

The matching process involves the main steps:

(1) Estimation of Propensity Scores:

First, a logistic regression model is employed to estimate the probability that each individual in the sample receives the intervention (i.e., participates in entrepreneurship education). This estimated probability, known as the propensity score, is divided by P(x) = Pr(T=1∣X), where T indicates whether the individual received entrepreneurship education, and X represents the matrix of covariates. Under the assumptions of unconfoundedness and common support, PSM can achieve covariate balance equivalent to that of traditional matching methods.

(2) Selection of Matching Methods:

To ensure robustness, we apply three widely used matching techniques:

➀ Kernel Matching: All control group observations are included in a weighted matching scheme, where the weights are determined by the distance in propensity scores from the treated observations. The default kernel function and bandwidth parameters are adopted in this analysis.

➁ Radius Matching (Caliper Matching): This method limits the absolute distance between propensity scores of matched pairs to ensure matching precision. The caliper width is set to 0.01 in this study.

➂ Nearest-Neighbor Matching: Each treated unit is matched with control units that have the closest propensity scores. We apply a caliper of 0.01 and set k = 4, meaning each treated unit is matched with four nearest neighbors to minimize the mean squared error.

(3) Estimation of Causal Effects:

After matching, we estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) to quantify the impact of entrepreneurship education on students’ DEI. The ATT is calculated as follows:

Here, Y1i and Y0i represent the potential outcomes for individual i with and without participation in entrepreneurship education, respectively.

Throughout the empirical analyses, kernel matching is employed as the baseline specification because of its efficiency in utilizing the full sample. Additionally, radius matching and nearest-neighbor matching are employed as robustness checks. Unless otherwise stated, all ATT results reported in the primary analysis are based on kernel matching.

Supplementary statistical analysesBeyond PSM, we conducted a series of regression-based analyses to examine further the mechanisms proposed in our conceptual framework.

First, we employed multiple linear regression models to assess the direct effects of entrepreneurship education—general, theoretical, and practical—on DEI.

Second, we tested the mediating role of creativity using the classic Baron & Kenny (1986) approach and Sobel test, followed by bootstrapped indirect effect estimation for robustness.

Third, to explore potential moderation effects, we introduced interaction terms between entrepreneurship education and the two dimensions of digital literacy (digital competence and social media use).

Finally, a set of robustness checks was performed using alternative model specifications, sample subsets, and matching algorithms. These complementary analyses further reinforce the robustness and deepen the explanatory power of the study’s findings.

All statistical analyses are conducted using Stata 17.0. By employing multiple matching methods, this study ensures the robustness of its findings and the validity of causal inferences.

Empirical analysisSample descriptionThe final analytic sample comprises 1188 university students, providing substantial diversity in demographic, academic, and socioeconomic characteristics (see Table 2). The average age is 23.41 years (SD = 1.94), with 54.55% female and 45.45% male participants. In terms of disciplinary background, 57.15% of students are enrolled in hard disciplines (e.g., engineering, computer science, natural sciences), while 42.85% come from soft disciplines (e.g., education, economics, literature). Additionally, students vary in terms of geographic upbringing. Approximately 32.66% were raised in rural areas, 25.42% in towns, 24.83% in small or medium-sized cities, and 17.09% in large urban centers. Only-child students make up 28.20% of the sample, while 71.80% have siblings. Furthermore, family background indicators reflect considerable heterogeneity. A majority of students report modest household financial conditions, and over 85% have parents whose highest education level is below a bachelor’s degree. The diverse regional, educational, and economic profiles increase the representativeness of the sample and reinforce the broader applicability of our findings within China’s digitally transforming higher education system

Sample characteristics.

SD: Standard deviation. Percentages may total > 100% because of rounding.

In this study, students are classified as having received entrepreneurship education if they participated in any form, either theoretical or practical. Table 3 presents a comparison of DEI and creativity between students who participated in entrepreneurship education and those who did not. The results indicate that entrepreneurship education is positively associated with both outcomes, providing initial support for H1 and H2.

Mean comparison of digital entrepreneurial intention and creativity by entrepreneurship education participation.

“Entrepreneurship Education” refers to students who have participated in either theoretical or practical forms of entrepreneurship education, or both. “Theoretical Education” and “Practical Education” represent participation in the respective subtypes. Values in parentheses represent standard deviations. Statistical significance of the differences was assessed using t-tests. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Students exposed to any form of entrepreneurship education reported higher DEI, with an average increase of 0.229 points compared to those without such exposure (p < 0.01). Among subgroups, those who received practical education demonstrated a greater increase (0.232 points) than those who received only theoretical instruction (0.150 points). These results support the notion that hands-on, experiential learning fosters stronger entrepreneurial motivation than purely theoretical instruction.

In terms of creativity, students who participated in practical entrepreneurship education reported significantly higher scores than non-participants (p < 0.01). At the same time, no significant difference was observed for those who received only theoretical education (p > 0.1). This further supports H2 and aligns with the broader finding in entrepreneurial research that creativity is more effectively fostered through active, applied problem-solving contexts than through passive theoretical exposure.

Results of average treatment effect on the treated (ATT)Table 4 presents the ATT estimates, assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education on DEI and creativity using kernel matching. The results show that students who received entrepreneurship education reported significantly higher DEI scores (ATT = 0.266, p < 0.01), providing strong support for H1. This effect is notably more substantial for those who participated in practical education (ATT = 0.257) than for those who only received theoretical instruction (ATT = 0.175), reinforcing the idea that experiential learning more effectively fosters entrepreneurial intent than abstract knowledge alone.

Average treatment effects of entrepreneurship education on digital entrepreneurial intention and creativity.

SE: Standard error. “Entrepreneurship Education” refers to treatment status defined by participation in either theoretical or practical education, or both. “Theoretical Education” and “Practical Education” indicate participation in the respective components. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

In terms of creativity, a key mediating variable, the findings reveal that students exposed to practical entrepreneurship education achieved significantly higher creativity scores (ATT = 0.203, p < 0.01) compared to their untreated peers. However, theoretical education had no statistically significant effect on creativity. These findings provide direct support for H2 and H2b, indicating that creativity functions as a mediating mechanism primarily activated through practice-oriented learning.

To ensure robustness, we employed two additional matching techniques: radius matching and nearest neighbor matching. As shown in Table 3, the results remain consistent across methods, with slight variations in ATT magnitudes but no change in the direction or statistical significance of the effects. This methodological consistency strengthens the validity of our causal claims, especially regarding the unique effectiveness of practical entrepreneurship education in promoting both creativity and DEI.

Validity check of the matching procedureTo evaluate the robustness of our results, we performed a comprehensive validity assessment of the PSM procedure. As shown in Table 4, the estimated ATT remained statistically significant across all three matching methods—kernel, radius, and nearest neighbor—demonstrating that the observed positive effects of entrepreneurship education on DEI and creativity are consistent and not sensitive to the choice of matching algorithm. This consistent methodology enhances the internal validity of the findings.

Further diagnostic checks confirmed improved covariate balance after matching. Specifically, the standardized mean differences of the covariates were significantly reduced, indicating a closer alignment between the treatment and control groups. This improvement helps mitigate potential confounding bias and supports the credibility of the causal interpretation.

Fig. 2 illustrates kernel density plots of the propensity scores before and after matching. The majority of observations fall within the region of common support, indicating that most treated and untreated students can be meaningfully compared. This ensures that treatment effects are estimated within a comparable subpopulation, which is a critical assumption for valid causal inference. Moreover, sharp reductions in pseudo-R² values and likelihood ratio chi-square statistics after matching provide additional evidence that the matching procedure successfully reduced systematic differences between the groups. Taken together, these results confirm the reliability of our matching approach and reinforce the robustness of the estimated treatment effects (see Figs. A1—A3 for further details).

Theoretical or practical dimensions of entrepreneurship educationTo further explore the heterogeneous impact of entrepreneurship education, we analyze the separate and combined effects of theoretical and practical components on students’ DEI and creativity (see Table 5 and Fig. 3). This comparison, based on varying combinations of educational exposure, highlights how different instructional formats influence entrepreneurial outcomes.

Heterogeneous effects of entrepreneurship education (based on education format).

SE: Standard error. Group definitions and corresponding education formats are provided in Table A6. *, **, and *** indicate significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively.

Students who received only theoretical education exhibited a significant increase in DEI (β = 0.175, p < 0.05), supporting H1. However, this group showed a statistically significant decline in creativity (β = −0.043). These results suggest that although theoretical instruction enhances students’ understanding and intentions, it may not effectively promote the divergent thinking required for creativity. The structured nature of theoretical content might limit opportunities for open-ended problem-solving, which is essential in digital entrepreneurship. This pattern aligns with the TPB, where perceived knowledge boosts intention, but a lack of experiential engagement constrains creative output.

In contrast, students who receive only practical education demonstrated a more substantial improvement in DEI (β = 0.260, p < 0.10). However, similar to the theoretical group, the effect on creativity was small and statistically insignificant (β = 0.026). This suggests that while hands-on training effectively promotes action-oriented motivation, it may lack the conceptual scaffolding required for deeper creative development. This observation reflects SCCT, which emphasizes that while mastery experiences enhance self-efficacy, cognitive input is essential for fostering creativity.

The most substantial effects emerged when students were exposed to both theoretical and practical education. This group showed significantly higher DEI (β = 0.371, p < 0.01) and creativity (β = 0.203, p < 0.01), confirming H1 and H2. The complementary strengths of the two formats, cognitive foundations from theory and experiential depth from practice, work together to activate both DEI and its cognitive antecedents, particularly creativity.

Further analysis confirms this complementarity. For students with theoretical education, the addition of practical training led to significant gains in intention (β = 0.200, p < 0.01) and creativity (β = 0.238, p < 0.01). However, adding theoretical instruction to students who had already received practical education did not significantly affect either outcome. This suggests that while practical education can independently drive entrepreneurial outcomes, theoretical instruction enhances its impact primarily when delivered first.

Lastly, when comparing students exposed only to theoretical education versus those with only practical education, the latter group showed stronger effects on intention. However, the difference was not statistically significant, suggesting that both formats make independent contributions. These findings underscore their complementary, rather than substantive, nature.

In summary, practical entrepreneurship education plays a critical role in shaping students’ digital entrepreneurial outcomes, especially when integrated with theoretical instruction. The dual-format model provides the most effective approach for fostering both intentionality and creativity, underscoring the value of experiential learning in digital entrepreneurship contexts.

Empowerment mechanism: the synergistic role of digital literacyTable 6 presents evidence that digital literacy significantly moderates the effect of entrepreneurship education on DEI, confirming H3. Students with higher digital ability benefit more from entrepreneurship education (ATT = 0.382, p < 0.01) than those with lower digital ability (ATT = 0.171, p < 0.10). This finding suggests that digital skills play a vital role in enabling students to absorb and apply entrepreneurship instruction effectively.

Heterogeneous average treatment effects of entrepreneurship education by digital literacy.

Students rating their digital ability as “Good” or “Very Good” were classified as high ability. Social media use was split at the mean score. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Standard errors are in parentheses.

A similar pattern is observed for social media use. Students with high engagement report greater increases in DEI (ATT = 0.315, p < 0.01) than those with lower engagement (ATT = 0.296, p < 0.01). Regular interaction with digital platforms likely increases exposure to entrepreneurial content, peer influence, and opportunity cues, amplifying the impact of formal education. These findings reinforce H3 and are consistent with SCCT, which emphasizes digital self-efficacy and enabling environments.

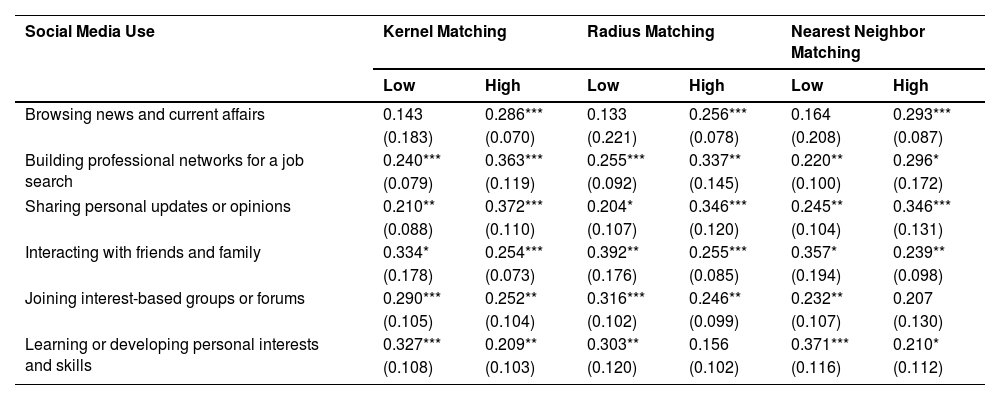

Further analysis explores how the purpose of social media use influences educational outcomes (see Table 7). Students engaging in growth-oriented activities, such as following current events, networking, or sharing insights, experience more substantial benefits from entrepreneurship education. For example, students using social media for professional networking report an ATT of 0.363 (p < 0.01), compared to 0.240 (p < 0.01) for those with lower engagement. Conversely, entertainment-oriented activities (e.g., chatting or joining hobby groups) yield weaker or inconsistent results. These differences support H3b and suggest that strategic, goal-driven digital engagement is equally beneficial in fostering DEI. It is the strategic, goal-directed approach, rather than the frequency alone, that amplifies the effects of entrepreneurship education.

Heterogeneous effects of entrepreneurship education by social media purpose.

The dependent variable is digital entrepreneurial intention. Social media use is categorized as “growth-oriented” (e.g., browsing news, professional networking, sharing updates) and “entertainment-oriented” (e.g., interacting with friends/family, joining interest groups). “Low” and “High” use groups are defined based on the mean value of each specific social media activity. *, **, and *** denote statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively. Standard errors are in parentheses.

To conceptualize these patterns, we classify social media use into two broad types: (1) Growth-oriented use, which includes job searching, professional networking, and informational learning. These activities support entrepreneurial development by enhancing opportunity recognition, resource access, and digital identity building. (2) Entertainment-oriented use: which includes chatting or group participation. While socially enriching, these uses provide less direct value for entrepreneurial learning. This distinction provides valuable guidance for designing entrepreneurship curricula. Incorporating modules that encourage purposeful digital engagement may significantly improve educational effectiveness. Conversely, unstructured social media use may dilute instructional impact.

In conclusion, digital literacy, particularly when purposefully applied, acts as a synergistic enabler of entrepreneurship education. Students with stronger digital abilities and more growth-focused social media habits derive significantly greater benefits from the same educational exposure. These results suggest that effective entrepreneurship education should integrate the development of digital competence and the shaping of digital behavior, alongside both classroom-based and experiential instruction.

Discussion and implicationsDiscussionThe findings of this study offer fresh insights into how entrepreneurship education cultivates DEI among university students, particularly within the context of China’s rapidly evolving digital economy. Grounded in the TPB and SCCT, the study empirically supports a combined mediation and moderation framework that highlights three key mechanisms: (1) the direct impact of entrepreneurship education on intention, (2) the mediating role of creativity, and (3) the moderating effects of digital competence and social media use. These findings contribute to the evolving discourse on digital entrepreneurship education and clarify how digital entrepreneurial ecosystems can be more effectively fostered through higher education interventions.

First, our results confirm the robust positive effect of entrepreneurship education on students’ DEI, reinforcing findings from prior literature (Turner & Gianiodis, 2018; Hoang et al., 2020). However, this study extends earlier work by disentangling theoretical and practice-oriented education, demonstrating that practice-oriented formats exert significantly stronger effects. This reinforces evidence from Nowiński et al. (2019) and Hu, Wang, & Zhang (2018), who found that experiential formats like competitions, incubators, and startup simulations foster deeper engagement and a more accurate perception of entrepreneurial feasibility. These formats not only activate behavioral intentions but also enhance entrepreneurial self-efficacy and foster creative agency.

Second, this study provides empirical validation for creativity as a mediating mechanism. While previous research (e.g., Shahab et al., 2019; Yar Hamidi et al., 2008) established creativity’s positive correlation with entrepreneurial intention, our model clarifies its causal positioning as a conduit between education and intention. Practical education fosters divergent thinking, problem-solving, and an innovative mindset, which are hallmarks of creative competence (Zampetakis & Moustakis, 2006; Belitski & Desai, 2016). This finding is especially relevant in digital entrepreneurship, where creativity is a dynamic capability for navigating technological disruption (Laguía et al., 2019). By framing creativity as both a cognitive and adaptive resource, our study strengthens the theoretical integration of the TPB, SCCT, and entrepreneurship education theory.

Third, this study highlights the moderating roles of digital competence and social media use, elucidating the boundary conditions that either amplify or constrain the influence of education. This echoes prior findings by Bachmann et al. (2024) and Santos et al. (2020), who emphasize that digital skills strengthen entrepreneurial action by enhancing opportunity recognition and reducing perceived barriers. Furthermore, we operationalized digital literacy as a two-dimensional construct—digital competence and social media use—and empirically validated their differential effects (Rodrigues et al., 2019; Jacobson et al., 2020). While digital competence enhances students’ ability to apply educational content in practice, growth-oriented use of social media fosters entrepreneurial awareness, improves access to information, and encourages peer interaction, as theorized by Kaplan & Haenlein (2010) and Teo (2016). In contrast, hedonic or entertainment-based use was shown to diminish this pathway, confirming Ye (2024)’s distinction between cognitive and hedonic media engagement.

Finally, these findings align with recent systematic reviews that advocate for rethinking entrepreneurship education within the context of broader digital entrepreneurial ecosystems. For example, Sahut et al. (2021) and Elia et al. (2020) emphasize that universities must evolve from knowledge providers into ecosystem enablers, which are institutions offering not only instruction but also access to entrepreneurial networks, digital platforms, and collaborative innovation spaces. Similarly, Thai et al. (2023) highlight the importance of integrating educational programs within dynamic digital ecosystems to support opportunity recognition and venture creation. Our results support these perspectives by demonstrating how the interplay of education, creativity, and digital competence enhances students’ readiness for entrepreneurial action in digital contexts. These insights contribute to an emerging consensus that digital entrepreneurship education must be both experiential and ecosystem-embedded to prepare students for entrepreneurial engagement in technology-driven contexts fully (Garcez et al., 2022; Portuguez Castro et al., 2023).

Although this study offers valuable insights into the role of entrepreneurship education, it is not without its limitations.

First, although the sample includes students from diverse disciplinary backgrounds, all data were collected from a single university in Guangdong. This institutional concentration limits the external validity of the findings, as it may not adequately reflect variations across different educational systems or regional cultures. Future research should broaden the sampling frame to include multiple universities from diverse regions or countries.

Second, the study’s cross-sectional design constrains its ability to infer causal relationships or assess long-term effects. Future studies could employ longitudinal or experimental designs, such as randomized controlled trials, to examine the developmental impact of entrepreneurship education more effectively.

Third, creativity was measured using a single-item Likert scale. While this approach can be justified under certain constraints, it may be vulnerable to measurement error and limited construct validity. Future research is encouraged to use validated multi-item scales to enhance reliability and ensure comprehensive conceptual coverage.

Finally, while this study explores the moderating role of social media use, it does not fully unpack the mechanisms through which different types of social media engagement influence DEI. Future research could adopt a mixed-methods approach to investigate the underlying processes, such as information dissemination, peer support, and online networking, which mediate the effects of entrepreneurship education.

Practical implicationsAs the digital economy rapidly reshapes global development, China’s “Digital China” strategy positions university students as central drivers of innovation. Enhancing their DEI is essential for national competitiveness in this new era. Based on our empirical findings, we present actionable implications for higher education institutions, educators, and policymakers aiming to foster digitally competent and creative entrepreneurs.

First, entrepreneurship education must shift from isolated instruction to an ecosystem-oriented, experience-based model. Our study shows that practice-oriented education, such as simulations, entrepreneurial competitions, and startup labs, has a significantly more substantial effect on DEI than theoretical content alone. Therefore, universities should prioritize curriculum reforms that integrate experiential formats, ideally supported by entrepreneurship hubs, tech incubators, or cross-disciplinary projects. To maximize inclusivity, institutions should tailor content delivery based on students’ digital skill levels: those with high digital competence can be offered advanced modules focused on AI-based entrepreneurial strategies or digital platform innovation. In contrast, those with lower competence should first receive foundational digital training.

Second, growth-oriented social media use should be intentionally embedded into course design. Instead of treating social media merely as a communication tool, educators should incorporate platforms like LinkedIn, Xiaohongshu, or Zhihu into entrepreneurship assignments. For example, students may be asked to document their venture progress through professional posts, participate in entrepreneurial communities for feedback, or connect with startup mentors via social platforms. Additionally, universities can create official online spaces (e.g., course hashtags, alumni-led WeChat groups) to promote peer exchange and network building. These growth-oriented practices foster the construction of entrepreneurial identity and the recognition of opportunities, which are factors that are especially crucial in digital contexts.

Third, stronger university-industry collaborations can reinforce real-world applicability. Our findings emphasize the need to connect students with entrepreneurial ecosystems beyond the classroom. Policymakers should support this initiative through targeted incentives such as innovation vouchers, research co-creation grants, or tax deductions for companies that mentor student startups. Universities, in turn, can offer structured co-learning programs where students engage with industry partners to develop real products or services, share outcomes via social media, and receive iterative feedback.

Finally, policy support must explicitly address regional and digital inequalities, as rural and under-resourced institutions often face significant barriers in providing comprehensive entrepreneurship education. National and local governments should allocate targeted funding to build digital infrastructure, provide teacher training, and develop open-access resources on digital entrepreneurship. Additionally, educational performance metrics should begin to include indicators of digital entrepreneurship readiness, such as student startup engagement, digital project outputs, or participation in online innovation communities.

ConclusionThe accelerating wave of digital transformation, fueled by artificial intelligence and platform technologies, has positioned digital entrepreneurship as a core driver of economic innovation and societal change. Drawing on data from 1188 graduating students at a “double first-class” university in China, this study examined how entrepreneurship education shapes DEI through creativity and digital literacy. Our findings indicate that practice-oriented education, such as innovation competitions and startup simulations, has a significant impact on DEI. Creativity serves as a crucial mediating mechanism, while digital literacy, especially growth-oriented social media use, moderates the overall effect of entrepreneurship education on DEI. Students who engage with entrepreneurial content and networks online benefit more from education, while entertainment-oriented use may hinder its impact.

These insights carry significant implications for educators and policymakers. Universities should prioritize experiential learning formats while maintaining strong theoretical foundations and tailor course delivery to students’ levels of digital proficiency. Educators can integrate growth-oriented social media use into curricula by encouraging students to document entrepreneurial projects, participate in digital communities, or connect with mentors through curated platforms such as LinkedIn, Xiaohongshu, or WeChat. Meanwhile, policymakers should support this transition by addressing digital infrastructure gaps, incentivizing university-industry collaborations, and embedding DEI indicators into educational performance evaluations. Together, these efforts can foster robust digital entrepreneurial ecosystems that integrate education, creativity, and digital competence.

While this study offers both theoretical and practical contributions, it has several limitations. Data were collected from a single institution, which limits generalizability, and its cross-sectional design restricts causal inference. Future research should employ longitudinal or experimental designs and expand the sample across more diverse regions. Nonetheless, this study advances an integrated framework of entrepreneurship education that incorporates creativity and digital literacy. It offers concrete strategies for cultivating digitally capable, entrepreneurially minded graduates in an evolving digital economy.

FundingThis work was supported by the Guangdong Province General Philosophy and Social Science Project (GD24CYJ47), the Guangdong Province Educational Science Planning Project (Higher Education Special Program, 2023GXJK241), the Guangdong Province Graduate Education Reform Project (2019GJXM20), the Guangzhou Philosophy and Social Science Development “14th Five-Year Plan” 2022 Co-construction Project (2022GZGJ134), and the South China Agricultural University 2021 School-level Education Reform Project (JG21047).

Ethics approvalEthics approval has been received from College of Economics and Management, South China Agricultural University (Ref. 20231010).

CRediT authorship contribution statementYaoming Liang: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Ruiqi Chen: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Hanhui Hong: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. Sisi Li: Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Data curation. Li Han: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.