The motives for starting a business among university students represent a current and important topic of scientific research. A key scientific premise of this approach is that significant research has demonstrated the importance of entrepreneurial activities by university-educated entrepreneurs in contributing to economic and social development worldwide. This study aims to identify the key factors that determine the propensity of university students to engage in entrepreneurship in selected Central European countries and to present a comprehensive model. The empirical research, focused on investigating university students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurial opportunities, was conducted in the V4 countries (Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic) between March and June 2024. The research included 2310 respondents, defined as students currently studying at higher education institutions providing economic-social, university, or college education. Data collection was conducted using Google Forms. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to evaluate the statistical hypotheses. The strongest influence on university students’ propensity to engage in entrepreneurship was demonstrated by government support for entrepreneurship. The second most significant factor was the quality of the macroeconomic environment, followed by access to external financing. The final statistically significant factor in the model was the effect of education. Surprisingly, factors such as the quality of the entrepreneurial environment and the perceived advantages and disadvantages of entrepreneurship did not show a statistically significant effect on shaping students’ entrepreneurial inclination. The results of this study are relevant not only for the academic community but also for policymakers and education management, as they reveal considerable gaps in the field. These findings provide clear signals to national government officials that entrepreneurship education receives insufficient attention at universities in the selected Central European countries. Furthermore, a broader societal debate on the importance of entrepreneurship among university-educated individuals should be encouraged, as they are better positioned to ensure sustainable company growth through continuous innovation and the application of sophisticated business management approaches.

The propensity of university students to engage in entrepreneurship can be considered a predisposition, motivation, or interest in starting and developing entrepreneurial activity either during their studies or after graduation. This propensity includes the ability and willingness to be entrepreneurial, as well as the willingness to take risks and invest time, energy, and resources in developing entrepreneurial ideas.

Several diverse factors can determine a student’s propensity for entrepreneurship. Some of the most important factors include personal characteristics (initiative, confidence, ambition, and innovative thinking), upbringing and social environment, education and experience in entrepreneurship, market opportunities, and access to external financing (Cheong & Hoang, 2021; Farhangmehr et al., 2016; Kromidha et al., 2024; Tredevi, 2016).

University-educated entrepreneurs significantly contribute to shaping the economic and social environment. A university education provides knowledge and skills that promote strategic thinking (Gallo et al., 2023), better market orientation, sound knowledge of legal relations, and awareness of international business trends. Universities are often a source of innovation and the latest technologies, which can kick-start innovative entrepreneurship after graduation (Bergmann et al., 2016; Gerstein & Hershey, 2016; Pisica et al., 2024; Tredevi, 2016). University-educated entrepreneurs are better positioned to address major trends in entrepreneurship, such as technological challenges, business sustainability, market globalisation, digitalisation, ethical business practices, and the implementation of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) concepts. Several studies have confirmed that businesses led by individuals with university degrees have a higher probability of long-term success, as these entrepreneurs are more capable of planning, managing resources, and responding effectively to market changes (Belas et al., 2016; Farhangmehr et al., 2016; Khan et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2024).

Based on an analysis of relevant scientific sources, this study defines the key economic and social factors that determine university students’ propensity to engage in entrepreneurship in Central European countries. It aims to present a comprehensive model and quantify the intensity of individual factors within this model based on extensive empirical research. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to evaluate the statistical hypotheses.

Young people are often considered drivers of innovation and change. Therefore, understanding the factors that motivate or discourage them from pursuing entrepreneurship is essential. This study aims to provide empirically based findings to enhance the understanding of future entrepreneurs’ needs. The results can inform the development of targeted policies and programmes to support young entrepreneurs. Through the study, we aim to achieve a holistic understanding of students’ entrepreneurial ambitions using interdisciplinary approaches. The study addresses a research gap through comparative analysis to objectively assess differences and the impact of external conditions on the entrepreneurial ambitions of young people. For the research implementation, countries that have received limited attention on this issue were selected.

Several studies have examined the individual effects of student motivations on entrepreneurial propensity using indices and models (e.g., Dinis, 2024; Dvorsky et al., 2019a; Khuram et al., 2022; Pham et al., 2023). Since a comprehensive view considering various factors and their interactions remains absent in existing literature, this study seeks to fill that gap through a comparative analysis of several Central European countries. The authors’ motivation is to create a unique, comprehensive model of students' entrepreneurial propensity and its significant influencing factors. A complete understanding of the dynamics of the entrepreneurial environment, based on such a view, can lead to more effective support for youth entrepreneurship. Knowledge of the key factors influencing students' entrepreneurship propensity provides a foundation for better understanding and guiding activities for other stakeholders as well. The empirical research in this study aims to provide valuable insights to that end.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the findings of important studies published in this field. Section 3 describes the aim, methodology, and data collection. Section 4 presents the research results and the evaluation of the statistical hypotheses. Section 5 discusses the results, followed by the study’s conclusions.

Theoretical backgroundEngaging in entrepreneurship is a significant decision for young people. The entrepreneurial mindset of university students in Central Europe has become an increasing focus of research in recent years, as their entrepreneurial activity can make a major contribution to economic growth and innovation in the region (Cheng, 2023; Lyu et al., 2023). Entrepreneurship is on the rise, especially in areas where innovation and digitalisation play a major role. Educational institutions, government support, and the development of international networks can all help young people become successful entrepreneurs, thereby contributing to the region’s economic and social development. Entrepreneurship is influenced by several factors, including the structure of the education system (Boldureanu et al., 2024) and the economic, social, and cultural environment (Pyrkosz-Pacyna et al., 2021).

The past and present of entrepreneurial attitudesTo understand the entrepreneurial attitudes of young people today, the socioeconomic background influencing the evolution of these attitudes must be briefly explored. Over the last three decades, young people’s entrepreneurial attitudes have undergone significant changes, shaped by economic, technological, and social processes. Entrepreneurship has been influenced by various factors, such as globalisation, technological development, changes in education, and economic crises. The V4 countries (Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland, and the Slovak Republic) have followed a similar development path since the regime change due to their shared historical background. Therefore, this overview highlights only the features where marked differences exist in their development over the past decades (Ambroziak et al., 2020).

The 1990s were an era of market economies and new opportunities. In East-Central Europe, the emergence of market economies after the regime change brought new prospects for young people. However, entrepreneurial attitudes were not yet widespread, as secure jobs and government employment were the preferred career paths for most. Initially, entrepreneurship was mainly inspired by foreign models and newly available market opportunities, but the regulatory environment and lack of start-up capital posed major obstacles for many young people (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, 2002). In Hungary, the liberalisation and privatisation of the economy facilitated the emergence and development of SMEs. The state supported the creation and operation of enterprises through various programmes. Similar privatisation programmes and financial incentives were launched in the other V4 countries. As part of the transition to a market economy, all four countries reformed their legal and regulatory environments to support entrepreneurship and introduced entrepreneurship programmes into the education system (Kézai & Skala, 2024). In the 1990s, research on university students’ entrepreneurial activities focused on raising awareness of the importance of this issue, as reflected in Anton et al. (1996).

The 2000s were characterised by European Union (EU) accession, SME integration, digitalisation, and the emergence of a start-up culture. Technological advances and the spread of the internet gave a new impetus to young entrepreneurs. The rise of e-commerce, the IT industry, and innovative solutions enabled an increasing number of young people to start businesses. The example of Silicon Valley, with the global success of start-ups such as Google and Facebook, served as inspiration. The education system responded to these changes with the growing inclusion of business and entrepreneurship courses in university curricula. After joining the EU, SMEs gained access to grants and programmes to improve competitiveness. Poland, in particular, benefited from EU structural and cohesion funds. Programmes such as the Innovative Economy Operational Programme (2007–2013) promoted innovation and competitiveness. The state encouraged enterprises to modernise and enter foreign markets, offering tax incentives to support investment. In all four countries, the adoption of EU regulations and legal harmonisation improved the business environment and reduced administrative burdens (Kézai & Skala, 2024). Nevertheless, red tape and tax systems continue to challenge businesses. In Hungary, the education system emphasised lifelong learning and the development of entrepreneurial skills, aligning with EU directives. Polish universities and research institutes developed increasingly close ties with industry. Research during this period focused on the importance of education and the exploitation of the potential of start-ups (Klapper, 2006; Tredevi, 2016).

The 2010s were marked by the aftermath of the economic crisis and a rise in self-employment, prompting an emphasis on stabilisation and digitalisation. The impact of the 2008 economic crisis encouraged many young people to seek alternative sources of income. The uncertain labour market led many towards self-employment and small businesses. At the same time, business incubators, venture capital, and EU subsidies became key opportunities for young entrepreneurs. Social entrepreneurship also gained prominence, aiming not only for profit but also for solving social issues. Increasingly, young people envisioned businesses aligned with sustainability and community values. In Hungary, the state played a significant role in SME financing, notably through the Széchenyi Card Programme and MNB’s growth loan programmes. EU tenders, such as the GINOP (Economic Development and Innovation Operational Programme), provided additional funding. Tax incentives improved SME competitiveness. Multinational companies also strengthened partnerships with local supplier SMEs. In Poland, the ‘Start in Poland’ programme supported innovation and start-up development. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, EU funding was also instrumental. Education reforms introduced dual training in Hungary, prioritised vocational training in Slovakia, and encouraged closer collaboration between research institutions and universities in Poland and the Czech Republic, which have strengthened their links with a focus on STEM fields (Valaskova et al., 2022). Research during this time focused on opportunities arising from the economic crisis, state support, subsidies, and the likelihood of entrepreneurial success (Bekeris, 2012; Belas et al., 2016; Dvorsky et al., 2019).

The 2020s represent the peak of digitalisation. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced new challenges that significantly affected young people’s entrepreneurial attitudes. Teleworking, digital services, and online businesses became more valued, while traditional forms of entrepreneurship have often struggled. Young people have shown increasing interest in e-commerce, influencer marketing, and online consultancy. Members of Generation Z and Alpha, growing up as digital natives, are building businesses rooted in technology, automation, and sustainability. Ethical consumption, environmental protection, and innovation now play a growing role in business decisions (Mari et al., 2024). In all four countries, digitalisation is a strategic priority, alongside ‘green’ programmes and efforts to create sustainable business conditions. In Hungary, inflation and the energy crisis presented new challenges, mirrored by similar issues in Slovakia. Meanwhile, innovation and exports have grown in the Czech Republic, and Poland’s start-up sector continues to develop. However, the energy crisis has impacted all four countries. Education has increasingly focused on digital skills, innovation, and sustainability (Semrádová Zvolánková & Krajčík, 2024). Recent research on business start-ups explores entrepreneurial competencies, sustainability strategies, digital marketing, and artificial intelligence (Bardales-Cárdenas et al., 2024; Pham et al., 2023; Rahaman et al., 2024).

International research has examined factors influencing the entrepreneurial propensity, ideas, and attitudes of young people in the recent past and today. Prasannath et al. (2024) found that different approaches are needed across economic sectors and that sector-specific goals should guide business support policies. Zhang et al. (2022) explored the impact of government support on entrepreneurial competencies, global competencies, self-efficacy, and behaviour among international students, offering a theoretical model to guide entrepreneurship policy aimed at tackling youth unemployment and balancing labour market supply and demand. Public support can enhance the competitiveness of young entrepreneurs both locally and internationally. Grants often fund innovation and research and development (R&D) projects, allowing students to develop new technologies and increase the value of their businesses in global markets. Onileowo (2024) and Onileowo and Muharam (2023) found a positive relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth, catalysed by government policy. Building on this, Kromidha et al. (2024) examined the exploitation of individual innovation aspirations. Using the theory of discursive institutionalism, they analysed the role of policy in shaping entrepreneurial ecosystems. Their findings revealed tensions between collective aspirations and individual goals, leading to the proposal of a generative institutional discourse model to address this issue. Buffart et al. (2020) examined the impact of public resources on entrepreneurial growth and found that policymakers often adopt a ‘picking winners’ approach based on past performance indicators—an approach that may not always foster entrepreneurial motivation.

Impact of macro- and micro-environmentCheong and Hoang (2021) adopted a similar line of thinking to investigate this issue. They investigated the impact of macroeconomic variables and firm-specific factors (firm size, leverage, liquidity, sales growth, and previous year profitability) on firm performance. Their results show that historical profitability, firm size, and leverage directly affect firm performance. Bekeris (2012) investigated the relationship between firms’ financial indicators (such as profitability) and macroeconomic factors. Among the selected macroeconomic indicators—inflation, average wages, number of firms, and monetary base—none were statistically significant or strongly correlated with firm profitability. Issah and Antwi (2017) examined firm performance in relation to other macroeconomic conditions. Their results indicated a clear correlation; however, sector-specific analysis revealed a mixed picture. The relationship between entrepreneurship and other macroeconomic indicators (such as access to credit, the economic confidence index, inflation rate, foreign direct investment, unemployment rate, and industrial production index) has also been the focus of research (Tomak, 2018; Bal-Domańska, 2021). The findings did not always reveal a direct correlation, and researchers reported differing effects, especially concerning unemployment. The above research demonstrates that while many macroeconomic factors affect firms, there is no consistent direction regarding which factors directly influence them.

Entrepreneurship and its functioning are also influenced by the availability of external sources of finance (bank loans, venture capital, public subsidies, and private investment). The extent of access to such financing largely depends on a country’s economic development, financial infrastructure, and government policies. Beltrame et al. (2023) investigated the impact of entrepreneurial orientation (EO) on access to credit for SMEs. Their results show that proactiveness, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness are important constructs that enhance firm competitiveness and, consequently, access to bank finance. Another study found a significant positive effect of financial literacy on access to external finance (Fachrurazi et al., 2023).

Interestingly, Le et al. (2024) found that identifiable intangible assets improve firms’ access to both debt and equity financing. In more developed countries, external financing is more readily available and offered on more favourable terms, while in developing regions, the focus tends to be on alternative solutions and international support.

The importance of educationThe strong role of education is evidenced by studies that have examined the impact of different aspects of education on entrepreneurial competences, preparedness and knowledge. The study by Bardelas-Cárdenas et al. (2024) confirmed that students’ entrepreneurial competencies are significantly and positively related to the development of the local economy. Dinis (2024) evaluated the impact of entrepreneurship curricula on students’ entrepreneurial attitudes, perceptions of social norms, and entrepreneurial intentions in a secondary school setting. The positive correlations in the results suggest that entrepreneurship education should begin before university studies. Pham et al. (2023) tested the role of students’ knowledge and technological innovation skills. Education enhances entrepreneurial motivation, while students’ technological innovativeness moderates the relationship between entrepreneurial motivation and the intention to create a digital venture. Alkaabi and Senghore (2024) investigated the importance of innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactivity in the entrepreneurial motivation of engineering students. Positive effects of education include boosting young people’s self-confidence, developing their skills, encouraging innovation and creativity, facilitating networking and mentoring, developing risk tolerance and resilience, and increasing economic impact and employment (Braunerhjelm & Henrekson, 2024; Wasilczuk & Karyy, 2022). Furthermore, the relationship between students’ emotional competence and entrepreneurial behaviour has been studied. The results showed that emotional intelligence has a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial intention (Nwibe & Ogbuanya, 2024). The distinctive behaviour of Generation Z was analysed by Alkaabi and Senghore (2024), who found that conscientiousness and neuroticism significantly affect their entrepreneurial intention. As more students gain entrepreneurial knowledge and access to necessary mentoring, skills, and networks, the region becomes more competitive and dynamic in the global market. Education not only increases the likelihood of starting new businesses but also ensures the long-term success and stability of existing ones.

Yusof et al. (2018) investigated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and willingness to engage in entrepreneurial practices. The results show that four entrepreneurial education variables—the role of the university, university curriculum, role models, and internship programmes—have a statistically significant relationship with entrepreneurial willingness. Similar research was conducted by Khan et al. (2024), who integrated theories of planned behaviour and human capital to evaluate the effectiveness of university entrepreneurship courses. The results identified three key antecedents of entrepreneurship: concept formation, opportunity identification, and implementation. Conceptualisation emerged as the most important predictor, followed by opportunity identification. The effect of education was the weakest on students’ entrepreneurship (a finding confirmed by the current research).

Entrepreneurship is linked to personal fulfilment and wealth creation, both of which are crucial (Wiklunda et al., 2019). Zhang et al. (2021) showed that entrepreneurial identity induces affective rumination about work, which reduces subjective well-being (Maalaoui et al., 2020; Ammiratoa et al., 2024). Nonetheless, entrepreneurship fosters innovative thinking and the generation of fresh ideas, enabled by creativity and adaptability (Fernández-Bedoya et al., 2023; Thurik et al., 2024). Young entrepreneurs are more willing to take risks and to develop their technological skills, especially digital competencies.

While young people have many advantages in innovation, risk-taking, and technological competence, they may be hampered by a lack of experience, limited financial resources, and challenges in establishing market credibility.

Entrepreneurial education plays a key role in starting a business, according to several authors. On the other hand, the formation of young people's attitudes is more complex in the context of entrepreneurship. Their attitudes are shaped by various stakeholders, such as family, friends, the political situation in the country, entrepreneurial role models, and so on.

Entrepreneurial attitudes of students in the V4 countriesThe attitude of young entrepreneurs in the Visegrad countries (Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia) has been influenced by similar historical and economic factors, although different opportunities and barriers have emerged in each country. Poland has the largest economy among the V4 countries and has shown rapid growth since EU accession (Kézai & Skala). A dynamic economy and well-developed industries provide opportunities for young entrepreneurs. The rapid development of the start-up ecosystem and a favourable tax environment also support them. Poland demonstrates a strong entrepreneurial spirit, with a strong presence of venture capital, as well as numerous incubators and accelerators. The Czech Republic benefits from a strong industrial and technological background, with young people showing significant interest in innovation and international markets. A developed market and direct access to Western markets offer attractive opportunities (Kelemen-Erdos & Szorat, 2025). The Czech government has introduced support measures for start-ups, including low taxes and fast-track start-up processes. The start-up ecosystem is highly developed, with many incubators and ample venture capital, though administrative barriers can pose challenges. Slovakia’s economy has grown since EU accession, but the market for young entrepreneurs is smaller and less dynamic than in Poland or the Czech Republic (Pilkova et al., 2016; Suchánková et al., 2024). Government subsidies and incubator programmes support start-up entrepreneurs, but red tape and market saturation may hinder growth. Despite the smaller market, young entrepreneurs in Slovakia can benefit from the rapid development of sectors such as the digital economy and green energy. Lower competition compared to larger markets creates unique opportunities for young people. Hungary’s economy has grown rapidly since joining the EU, but has experienced some stagnation in recent years (Gubik & Farkas, 2019). EU funds and government support stimulate business, but economic instability and frequent regulatory changes can create uncertainty. The entrepreneurial spirit among young people is not as strong as in neighbouring countries, although the start-up community has been steadily growing. The venture capital market in Hungary remains relatively small, and competition is fierce. The IT and digital sectors offer the greatest opportunities for new ventures. Among the V4 countries, Poland is considered the most entrepreneurial, while in the other countries, various administrative and economic factors can present barriers (Dvouletý & Orel, 2020). Despite their shared historical background, the factors influencing young people’s entrepreneurial ambitions differ in notable ways. The most typical influences (which we have focused on in our practical research) are presented below.

State aid for entrepreneurshipThe role of the state and state support for entrepreneurship is of crucial importance. The EU’s efforts and the support provided by individual countries can have a motivating effect in many ways. Soft loan schemes and grants, such as those available in Hungary for young entrepreneurs, reduce the financial risk of starting a business (Nyikos et al., 2020). Government grants can provide the seed capital needed to launch a business, encouraging students to pursue their entrepreneurial ideas. Public funds are often targeted to support areas such as the environment, health, or digital transformation, thus encouraging students to engage in ventures that align with social and economic goals. These incentives are particularly popular among young people in Central Europe, who are increasingly looking to start socially impactful and purpose-driven businesses (Pilkova et al., 2017). Previous research has shown that the availability of public resources directly impacts entrepreneurial propensity, as they not only offer financial support but also contribute to long-term development opportunities, market competitiveness, and practical knowledge for young entrepreneurs (Makay & Dory, 2023; Onileowo, 2024; Voda et al., 2020). While state aid can be a catalyst for entrepreneurial decision-making, other factors, such as macroeconomic conditions, must also be considered.

Macroeconomic factorsMacroeconomic factors significantly impact the success and growth potential of start-ups. Start-ups are particularly sensitive to changes in the economic environment, as they generally have fewer reserves and less market stability than larger, more established firms. Key influencing factors include economic growth, recession, inflation, financial stability, high unemployment, labour market conditions, interest rates, access to finance, tax incentives and subsidies, the regulatory environment, open trade opportunities, and trade restrictions. Vyrostková and Kádárová (2023) found a significant positive relationship between macroeconomic conditions (GDP per capita, regulatory quality index, and firm market capitalisation) and entrepreneurship. Conversely, there is a statistically significant negative relationship between entrepreneurship and the rule of law and public debt. Mitra et al. (2023) assessed the relationship between firms’ investment decisions and risk and how this affects firm performance. Their results show a significant positive relationship between firm performance and macroeconomic factors. Firm size, age, leverage, sales growth, and operating profit also affect performance. During periods when the economic environment is favourable, entrepreneurship and growth are more likely, while during recessions or unstable conditions, businesses must implement tighter financial controls and conduct more thorough risk analysis to survive. The macroeconomic environment also impacts the quality of the immediate business environment (Dvorsky et al., 2020), which profoundly affects how businesses operate. Therefore, in the following section, we focus on the impact of the business environment.

Direct business environmentThe wider business environment can either support or hinder entrepreneurship. It fundamentally determines how easy or difficult it is to operate, grow, and remain competitive in the market. A positive and supportive business environment stimulates entrepreneurship and enables start-ups to grow, while an unfavourable environment creates barriers to success. The business environment affects enterprises through several key factors, including the legal and regulatory environment, access to finance and capital markets, tax regime and incentives, labour market and education system, infrastructure and digital environment, market competition, and business culture. A supportive, well-regulated, and favourable tax environment with easy access to finance and skilled labour significantly contributes to the growth and competitiveness of start-ups. Conversely, an unfavourable business environment discourages entrepreneurship and increases operational risks, which can lead to start-up failure or limit growth potential. Godlewska and Morawska (2019) investigated the attitudes of Polish local and regional government institutions towards entrepreneurship support. They concluded that geographic location, political power, unemployment levels, area size, or debt levels did not significantly affect local governments’ behaviour in supporting entrepreneurship. Instead, the governance model, the type of local government, and the number of businesses operating within the jurisdiction influenced entrepreneurial support. Dvorsky et al. (2019b) sought to quantify the advantages and disadvantages of significant social environment indicators, including the determinants of entrepreneurial propensity, among university students in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Poland. Their results show that income irregularity and lack of time with family negatively affect entrepreneurial propensity in all three countries, while access to financial resources, better career prospects, and the potential for self-fulfilment have a positive impact. Brixiová et al. (2020) identified a link between access to finance and employment, while Abdalla (2024) confirmed the association between access to external finance and perceived risk. Motta (2020) examined the relationship between access to finance, project quality, and labour productivity. Access to venture capital in CEE countries remains much lower than in advanced economies, although the number of international investors in the region has increased in recent years. Local venture capital investors are emerging but generally operate on a smaller scale and with greater risk aversion. Access to external finance remains one of the key challenges in the EU, prompting the European Commission (EC) to launch several programmes aimed at improving the financial environment (Poderys, 2015). Bank lending often involves stricter conditions, and start-ups—especially those without adequate collateral—can struggle to secure credit. Smaller banking systems tend to have limited risk appetite, pushing start-ups towards alternative financing options, such as microfinance schemes. Several funding opportunities are available to EU countries, particularly grants for R&D and innovation. These grants and domestic incentives are important resources for businesses. In Poland, for example, several state-funded start-up programmes provide seed capital and mentoring to aspiring entrepreneurs (Dvorsky et al., 2019).

The quality of the business environment plays a crucial role in enhancing a country's economic development (Ma & He, 2024). Furthermore, a favourable business environment positively influences the entrepreneurial intentions of female university students in Latin America (Víquez-Paniagua et al., 2023). This factor is also significant in the context of sustainability and the development of the small and medium-sized enterprise sector (Belas et al., 2017).

The significance of educationSeveral studies stress the importance of education as a key driver for entrepreneurship, the development of the start-up ecosystem, and the creation of new innovative businesses. According to the EC, entrepreneurship is a learnable skill—you do not need to be born an entrepreneur to succeed in business. You can become one by developing an entrepreneurial mindset and skills. As Europe needs more entrepreneurs, all EU countries must promote this type of education. As mentioned above, the Central and Eastern European (CEE) region faces challenges such as lower entrepreneurial propensity, higher risk aversion, and more difficult access to finance and venture capital, with education playing a particularly important role in supporting start-ups and building the knowledge base of entrepreneurs. A wealth of education research highlights the relevance and importance of this topic. With the EU’s emphasis on promoting entrepreneurship and young people’s growing willingness to start and develop new businesses (Boldureanu et al., 2024), momentum for entrepreneurship education in the CEE region is building. Efforts are being made not only to foster entrepreneurial attitudes, mindsets, and skills that can lead to business creation and innovation but also to develop transversal skills that will help the future workforce become more resilient and adaptable. The latter is particularly important, as entrepreneurship is not suitable for everyone.

The OECD’s Local Economic and Employment Development Committee supports youth entrepreneurship practices (GEM, 2024), as does Econverse V4—the largest start-up simulation programme—supported by the Visegrad Fund, Aspen Institute CE, Orange, Baker McKenzie, and others. Its mission is to help the next generation of entrepreneurs develop business ideas while supporting international collaboration among young leaders. Econverse bridges the gap between traditional school education and the practical skills needed in today’s fast-paced start-up ecosystem by combining innovative teaching methods with real-world applications. It emphasises experiential learning, where students apply theory to real-world problems. This cross-border collaboration not only fosters a sense of regional unity but also prepares participants for the challenges of launching start-ups in a globalised economy (Blokker & Dallago, 2018). A growing number of universities in Central Europe, including Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, and Poland, are offering entrepreneurship training, incubator programmes and mentoring opportunities to support students in developing entrepreneurial skills. Many students are motivated to start their own businesses by a desire for independence, an interest in innovation, and a receptiveness to market opportunities (Boldureanu, 2024). However, a lack of adequate financial resources, entrepreneurial inexperience, and low risk-taking often act as barriers (GEM, 2024). Education not only increases the likelihood of launching new businesses but also ensures the long-term success and stability of existing ones.

The pros and cons of starting a businessThe definition of entrepreneurship is often debated. There are many advantages and disadvantages to starting a business as a young person, impacting both personal lives and broader economic and social development. These pros and cons are also linked to age, lack of experience, and the specific economic environment. Weighing these factors helps each individual decide what influences matter most in determining their entrepreneurial path. People typically start businesses for personal reasons. The benefits of entrepreneurship include increasing risk-taking among young people and developing technological and digital skills. Entrepreneurship programmes, incubators, and support from universities and public organisations assist during the early stages by offering mentoring, financial assistance, and valuable business contacts (Wang, 2020). Knowledge and innovation play a paramount role, positively impacting all other areas (Kraus et al., 2021; Weligodapola et al., 2023).

Among the difficulties is the lack of experience, often reflected in limited financial and business knowledge and management skills. At the same time, an overly optimistic view of education can have drawbacks (De Sordi et al., 2022). Young entrepreneurs may face difficulties in accessing venture capital (Rahaman et al., 2024). Trust issues, lack of networks, and an inability to manage stress-related tensions (Ziemianski & Golik, 2020) can also hinder progress. Mental strain and fear of failure may affect motivation and self-confidence (Yang et al., 2021). While youth entrepreneurship brings many benefits, particularly in terms of innovation, risk-taking, and digital competence, it is often limited by inexperience, financial challenges, and difficulty establishing credibility. Education programmes, incubators, mentoring, and public support can significantly help young people become successful entrepreneurs and strengthen the entrepreneurship landscape in the CEE region (Hartmann et al., 2022; Thurik et al., 2024).

Entrepreneurship willingnessUnderstanding the external environment and the factors associated with entrepreneurship—both positive and negative—is key to assessing the willingness of young people to become entrepreneurs. More and more young people are showing interest in entrepreneurship, especially in technology and online business models. New technologies, the spread of start-up culture, and digitalisation offer them opportunities to realise their ideas and access global markets. Although youth entrepreneurship in Central Europe has been growing, it still lags behind Western Europe in both levels of entrepreneurship and the number of businesses. The most important factors on entrepreneurial propensity among young people in Central Europe are higher education and access to public funding (Belas et al., 2017). This is confirmed by studies from Dvorsky and colleagues (Dvorsky et al., 2019a, 2021), conducted among students in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Their findings show that Czech students rated state support and education quality higher than Slovak students, but reported lower entrepreneurial propensity. Although more universities now offer entrepreneurship programmes, many students are unaware of the steps and challenges involved in launching a business. This is particularly true regarding financial and legal knowledge, often lacking among young entrepreneurs and causing difficulties in the early stages. Attention should be paid to public and EU support, incubators, accelerators and innovation hubs, especially in technology industries, which depend on young people’s creativity and digital skills. The rise in entrepreneurship is characterised by caution and risk aversion, likely due to social and economic uncertainty, and the lack of family or financial support. Martín-Navarro et al. (2023) also studied entrepreneurial propensity among Slovak and Czech students. Their results align with earlier research: Czech students have more confidence in state support, the macroeconomic environment, and the educational quality, yet Slovak students show higher optimism and a greater willingness to start businesses after graduation. An interesting correlation was investigated by Khuram et al. (2022), who studied the role of efficiency-oriented motivation in predicting entrepreneurial intention. Their results suggest that efficacy propensity influences entrepreneurial intent and that attitude and perceived behavioural control mediate the relationship between subjective norms and intention. Khattak et al. (2024) investigated how personal characteristics and competencies influence students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Their results show that gender, risk perception, career-related factors, and university education all significantly influence students’ interest and motivation to start a business. Bilan et al. (2019) investigated the impact of the university environment on students’ entrepreneurial propensity. They confirmed that entrepreneurship support programmes, mentoring, and hands-on training encourage entrepreneurship, while incubators and industry partnerships further foster entrepreneurial ambition.

Entrepreneurship among young people in the V4 countries is influenced by various macro- and micro-level factors. Economic stability, the legal and administrative environment, cultural attitudes, and access to entrepreneurial opportunities all determine whether young people are likely to start businesses. Grants, well-developed start-up ecosystems, and opportunities in innovative markets can help aspiring entrepreneurs, but bureaucratic burdens and competition may pose challenges. Our field research aimed to investigate the factors presented above.

Aim, methodology, and data collectionThis study aims to define the significant factors that determine the propensity of university students to engage in entrepreneurship in selected Central European countries—Slovakia (SR), Hungary (HU), Poland (PL), and the Czech Republic (CR)—and to present a comprehensive model.

Fig. 1 presents the action taken by the authors, including a geographic map of the V4 countries.

The empirical research focused on investigating the attitudes of university students towards entrepreneurship opportunities. It was conducted in the V4 countries (Slovakia, Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic) between March and June 2024 (during the summer semester of the academic year 2023/2024). The study comprised 2310 respondents, defined as students currently studying at higher education institutions providing economic-social, university, or college education. For each country, a localised version of the questionnaire was created in the respondents’ national language. Data collection was conducted using Google Forms, with security measures in place to prevent automated responses or computer-generated answers.

The first version of the questionnaire was developed by the research team (academic staff from V4 countries focused on the topic of entrepreneurial education among university students). Equally important was obtaining insights from students. In this phase, a total of 40 students participated (10 students from each country). Based on their feedback, the final version of the questionnaire was created. Several statements were modified to enhance students' comprehension.

The questionnaire consists of several parts. In the first part, questions covered the demographic characteristics of respondents. In the second part, questions were selected randomly. The target group was university students (hereinafter referred to as respondents). Respondents were asked to complete the questionnaire truthfully and were allowed to do so only once.

Data collection was facilitated by participating educational institutions, selected based on the following criteria (using stratified and proportional sampling): (i) geographical location (region of the country); (ii) field of study (economics, humanities, managerial, or technical); and (iii) level of study (bachelor’s, master’s or PhD). Questionnaire distribution was ensured by academic staff from participating universities or colleges. Another key criterion was that each country’s research sample should consist of at least 50 % of students enrolled in economics-focused study programmes. In total, the research sample included students from 34 universities: 16 in Slovakia and 18 in Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland combined.

The structure of respondents (total number, n = 2310) by V4 countries was as follows: Slovakia (SR) – 576 respondents (24.94 %); Poland (PL) – 595 respondents (25.76 %); Hungary (HU) – 527 respondents (22.81 %); and Czech Republic (CR) – 612 respondents (26.49 %). An analysis of the sample size for each country was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics. The results confirmed that the number of respondents exceeded the minimum required sample size by more than 1.2 times (n = 370).

Questionnaire and variablesThe questionnaire comprised 35 questions. Four questions focused on basic respondent identification: institution name, field of study, level of study, and gender. The remaining 31 questions explored respondents’ attitudes towards various defined statements related to willingness to engage in entrepreneurship, considering political, macroeconomic, social, personal, and educational system aspects.

Attitudinal responses were captured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = neutral, 4 = disagree, and 5 = strongly disagree). All questions were mandatory, and only one answer could be selected per question. To ensure consistency in responses, a control question was included. Respondents who answered this question in a significantly contradictory manner were excluded from the sample.

Table 1 shows the exact formulation of the items (Y – Dependent factor; X1, …, X7 – Independent factors).

Formulation of the statements in the questionnaire.

Note: F – Factor; I – Item (or statement); MIN – Minimum value; MAX – Maximum value.

Source: Own data collection.

Based on the results of the qualitative analysis, the following scientific hypotheses were formulated (Table 2).

Formulation of statistical hypotheses.

Source: Own data collection.

The statements for each construct (dependent and independent variables) in the questionnaire were formulated so that positive responses to the independent constructs (X1, …, X7) would lead to positive responses to the dependent variable (Y). The assumption of multivariate normal distribution for the variables (Y, X1, …, X7) was met.

SEM was used to evaluate the statistical hypotheses. Phase 1: Descriptive characteristics of the variables were presented. The reliability and validity of the questionnaire were verified, and the assumption of multivariate normal distribution was tested. Phase 2: Relationships between the statements and latent factors were verified using factor analysis, conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software. Phase 3: Causal relationships between the defined factors were evaluated using linear regression modelling.

The significance of the SEM model lies in identifying and quantifying the impact of statistically significant independent constructs (X1, …, X7) on the dependent construct (Y). The final SEM model of relationships between the factors was validated using model fit characteristics and was visually represented using IBM SPSS AMOS software.

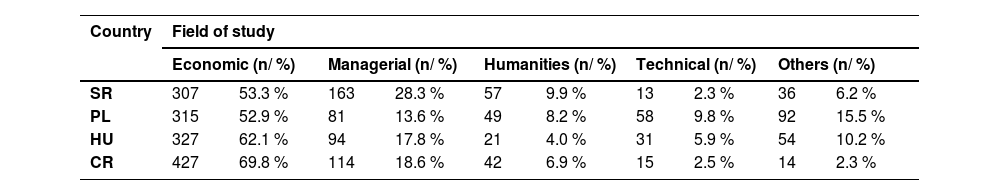

Structure of studentsTable 3 presents the results of the demographic structure of respondents according to the country of study.

Demographic structure of respondents.

Note: SR – Slovak Republic (n = 576); PL – Poland (n = 595); HU – Hungary (n = 527); CR – Czech Republic (n = 612).

Source: Own data collection.

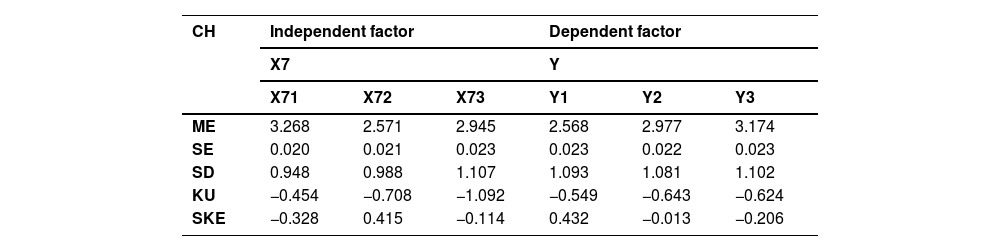

Tables 4, 5, and 6 present the results of the descriptive characteristics (CH – e.g., mean (ME), standard deviation (SD), and so on) of selected statements (X11, …, Y3) formulated in the questionnaire.

Results of descriptive statistics of statements of X1, X2, and X3.

Note: CH – Characteristics; ME – Mean; SE – Standard Error; SD – Standard Deviation; KU – Kurtosis; SKE – Skewness.

Source: Own data collection.

Results of descriptive statistics of statements of X4, X5, and X6.

Note: CH – Characteristics; ME – Mean; SE – Standard Error; SD – Standard Deviation; KU – Kurtosis; SKE – Skewness.

Source: Own data collection.

Results of descriptive statistics of statements of X7 and Y.

Note: CH – Characteristics; ME – Mean; SE – Standard Error; SD – Standard Deviation; KU – Kurtosis; SKE – Skewness.

Source: Own data collection.

The results presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5 show that the factors students agree with the most are the impact of education (X5) and the advantages of entrepreneurship (X6). Conversely, the factors perceived least favourably are the quality of the entrepreneurial environment (X3) and the disadvantages of entrepreneurship (X7). Factor X3 is directly related to state support (X1), the macroeconomic environment (X2), and external financing (X4), which are rated neutrally or slightly unfavourably. The results for factor X7 (tendency to disagree with statements X61, …, X63) are positive in the context of starting a business, as students generally do not perceive a lack of stable income or time for family as significant drawbacks.

Reliability and validity of statements in the questionnaireTable 7 presents the basic results of the reliability, consistency, and validity of the statements (e.g., X11, …, X13) related to the defined factors (e.g., X1).

Reliability and validity of items in the questionnaires.

Note: CA – Cronbach Alfa; FL – Factor Loading; KMO – Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test; CR – Composite Reliability; AVE – Average Variance Extracted; COM – communality; CI-TC – Corrected Item-Total Correlation.

Source: Own research results.

The results (Table 7) confirm that the reliability and validity of factors X3, X6, and X7 are not adequate, because: (i) the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) results are less than 0.6 (borderline acceptable); (ii) the Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) values are less than 0.6 (indicating poor reliability); and (iii) the corrected item-total correlation (CI-TC) values are less than 0.5 (indicating poor correlation between item and factor). Therefore, the values of factor loadings and communalities are not adequate. Based on the results (Table 2), the statistical hypotheses H3, H6, and H7 cannot be verified, as the statements formulated for factors X3, X6, and X7 do not form independent factors. However, the results for the connection between items and other factors are acceptable, based on the KMO, CA, CR, AVE, FL, CI-TC, and COM values.

Confirmation factor analysisThe empirical results of the KMO test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity are presented in Table 8.

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test and Bartlett´s test of sphericity.

| KMO | 0.815 | |

| BTS | Approx. Chi-square | 12,138.9 |

| DF | 105 | |

| SIG | 0.000* | |

Note: BTS - Bartlett’s test of sphericity; SIG – Significance; KMO - Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test; DF – Degrees of Freedom.

The results of the KMO test (Table 8) show a KMO value of 0.815, which exceeds the recommended threshold of 0.6. This indicates that the sampling adequacy is sufficient for conducting factor analysis. A value above 0.8 is considered ‘meritorious’. The approximate chi-square value is 12,138.9 with 105 degrees of freedom (DF), and the significance value (SIG) is 0.000, which is below the commonly used significance level of 0.001. This confirms that the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix, making factor analysis appropriate. These results (Table 8) confirm that relationships exist between variables, validating the factorability of the dataset.

The empirical results of the discriminant validity of the model and rotated factor matrix are presented in Table 9.

The discriminant validity of the model and rotated factor matrix.

Note: Y: Students' entrepreneurial inclination; X1: Importance of state support for entrepreneurship; X2: Influence of macroeconomic factors on starting a business; X4: Access to external financing; X5: Influence of education on entrepreneurship. Extraction method: Maximum Likelihood; Rotation method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalisation; Rotation converged in 5 iterations.

Source: Own research results.

The empirical results (Table 9) confirm that the connection between items and factors is adequate based on the loadings of manifest items. Without the results in Table 4, the results of the total variance explained (TVO) are important. The initial eigenvalues for each factor are as follows: factor X2: total = 4.315, % of variance = 26.968, cumulative % = 26.968; factor Y: total = 2.387, % of variance = 14.920, cumulative % = 41.889; factor X1: total = 1.708, % of variance = 10.677, cumulative % = 52.565; factor X5: total = 1.201, % of variance = 7.507, cumulative % = 60.072; factor X4: total = 1.034, % of variance = 6.464, cumulative % = 66.536. Factor X2 is the most significant contributor to the explained variance, while factor X4, though the smallest, still adds to the cumulative variance. These results indicate that the selected factors (X2, Y, X1, X5, and X4) collectively explain a significant portion (66.536 %) of the total variance in the dataset.

Table 10 presents the results of collinearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF) for manifest items, and the results of communalities for each item, estimated using the maximum likelihood (ML) method.

Empirical results of collinearity and communalities of items.

Note: * VIF coefficient was calculated only for items of independent factors; VIF – Variance inflation factor; COM – Communality.

Source: Own research results.

The results (Table 10) confirm that VIF values for independent factors range from 1.307 to 2.267. These values are below the critical threshold of 5, indicating no severe multicollinearity among the independent variables. Thus, the independent factors do not significantly overlap in their contribution to the model. Additionally, communality values range from 0.647 to 0.807, indicating that a substantial portion of the variance in each item is explained by the factors. The highest communalities are observed for items Y1 (0.807) and Y3 (0.799), suggesting strong relationships between these items and their respective factor Y. Lower communalities (e.g., X13: 0.647) suggest that these items contribute less to the construct, but are still within an acceptable range.

Constructing the SEM model and evaluating statistical hypothesesThe final model of entrepreneurship propensity of university students in Central European countries, constructed using SEM, is shown in Fig. 2.

The results presented in Fig. 2 are interpreted as follows: (i) the most influential factor is state support (X1), which has the strongest effect on Y (β = 0.42), highlighting the importance of government policies and support mechanisms in shaping students’ entrepreneurial attitudes; (ii) moderate contributions from macroeconomic factors (X2, β = 0.36) and access to financing (X2, β = 0.28) suggest that external conditions and financial accessibility play significant roles; (iii) the least influence comes from education (X5, β = 0.20), indicating that while education contributes to entrepreneurial inclination, its effect is less pronounced compared to other factors.

The quality results of the achieved SEM model (number of distinct sample moments = 105, number of distinct parameters to be estimated = 31, DF = 74) are summarised in Table 11 based on the fit summary characteristics.

Empirical results of the fit summary.

| Summary FIT | Chi-square p-value | CMIN/DF | RMSEA | GFI | CFI | NFI | RMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEM model | 0.029 | 0.854 | 0.032 | 0.874 | 0.728 | 0.784 | 0.017 |

| AV | <0.05 | <−2.0;2.0> | <0;0.05> | <0.95 | <0.95 | <0.90 | <0;0.05> |

Note: Acceptable values (AV) of Summary Fit Characteristics: GFI - Goodness of Fit; CMIN/DF – The minimum discrepancy; CFI - Comparative Fit index; RMSEA - Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; NFI - Normed Fit index.

Source: Own research results.

The SEM model with fit summary (Table 11 and Fig. 2) has the following types of variables: total number of variables = 33; number of observed variables = 14; number of unobserved variables = 19; number of exogenous variables = 18; number of endogenous variables = 15. The summary fit characteristics (Table 11) confirm that the final SEM model is statistically significant, with all values falling within acceptable ranges.

Table 12 presents the results of evaluating the formulated statistical hypotheses, specifically the relationships among the latent factors of the research.

The results from Table 12 are as follows: (i) the most significant factor is X1: Hypothesis 1 was accepted (β = 0.424; p < 0.001); (ii) the moderately significant factors are X2 and X4: macroeconomic factors have a significant effect (β = 0.359; p < 0.001), and access to financing plays a smaller but meaningful role (β = 0.282; p < 0.001); and (iii) education (X5) contributes positively but has the weakest impact (β = 0.202; p < 0.01). The hypotheses regarding the influence of factors X3, X6, and X7 on the propensity to engage in entrepreneurship were rejected.

DiscussionResearch findingsThis study’s empirical results on the entrepreneurship propensity of university students in the V4 countries revealed several interesting findings.

First, the basic evaluation of the statements in the formulated questionnaire indicates that students most strongly agree (M = 2.329) with statements regarding the quality of education they receive at the university. Students also positively perceive the advantages of entrepreneurship, such as enabling better career growth and providing interesting job opportunities (M = 2.336), as well as allowing the full utilisation of their abilities (M = 2.053). Conversely, students least agree with statements regarding state support for entrepreneurship (M = 3.255). The results suggest that students remain uncertain about whether they will pursue entrepreneurship after completing their university education. Arguably, the above factors have failed to effectively support their motivation for entrepreneurship.

Second, factors such as (i) state support, (ii) the macroeconomic environment for starting a business, (iii) access to external financing, and (iv) education on entrepreneurship have a statistically significant and positive effect on the entrepreneurship propensity of university students. Conversely, factors such as (i) the quality of the entrepreneurial environment for starting a business, (ii) advantages of entrepreneurship, and (iii) disadvantages of entrepreneurship cannot be evaluated, as the factor analysis indicates that they do not form separate factors.

Third, the final SEM model of students’ entrepreneurial inclination is statistically significant, explaining more than 66 % of the total variability in students’ attitudes towards the defined statements. However, approximately 33 % of the variability remains unexplained, indicating the presence of additional independent factors not included in this investigation.

Fourth, state support is the most significant driver of students’ entrepreneurial inclination, creating favourable conditions for starting a business and providing financial support. This effect is the strongest (β = 0.42) among all defined factors. Additionally, a positive perception of statements related to factor X1 (state support) positively influences students’ entrepreneurial inclination.

Fifth, macroeconomic factors (β = 0.36) and access to financing (β = 0.28) also have a moderate, positive, and statistically significant effect on students’ entrepreneurship propensity. State support for the macroeconomic environment—through favourable policies and conditions to encourage start-ups—is the most significant indicator forming the macroeconomic environment factor. Support for entrepreneurial activities, such as reasonable credit terms and interest rates from commercial banks, constitutes a factor of access to external financing. These factors play a smaller role than state support.

Sixth, education on entrepreneurship, based on students’ attitudes, is a statistically significant factor with the smallest impact (β = 0.20). It primarily refers to the quality of the educational system at the university and the knowledge acquired, which supports starting a business. In the comparison of the role of state support and education on entrepreneurship, the findings showed that the role of state support (β = 0.42) is more than twice as strong as that entrepreneurship education (β = 0.20).

International context of research resultsThis study confirms that university education aimed at supporting entrepreneurial activities is a statistically significant factor. This primarily concerns the quality of the educational system and the relevant knowledge students acquire, which supports their interest in entrepreneurship. Some signals in our research indicate that entrepreneurship education needs improvement and better adaptation to current market needs. Updating the content of educational programmes and adapting teaching methodologies, such as including real and practical experience, project work, and collaboration with local businesses and start-ups, can potentially increase students’ interest in entrepreneurial activities.

The research also confirms the importance of government support (Buffart et al., 2020; Onileowo & Muharam, 2023; Zhang et al., 2022), the macroeconomic environment (Dvorsky et al., 2020; Issah & Antwi, 2017; Bal-Domańska 2021; Vyrostkovou & Kádárovou, 2023; Mitrom et al., 2023), and access to external financing (Bardelas-Cárdenas et al., 2024; Boldureanu et al., 2024; Braunerhjelm & Henrekson, 2024; Dinis, 2024; Pham et al., 2023; Wasilczuk & Karyy, 2022) in shaping university students’ propensity to become entrepreneurs. Among these, state support is the most influential factor, as confirmed by the highest coefficient in the SEM model. Government measures, such as subsidies, interest-free loans, or tax breaks, have a direct impact on students’ decisions to become entrepreneurs.

Similarly, the quality of the macroeconomic environment plays a significant role. Students expressed that favourable macroeconomic indicators (e.g., GDP, employment rate, inflation) support entrepreneurial activities. Regional differences were also identified in the analysis, setting this study apart from others that often overlook local specificities.

Our findings further suggest that environmental sensitivity and responsible entrepreneurship are key elements, as noted by authors such as Brixi et al. (2020), Kyriakopoulos et al. (2020), and Beltrame et al. (2023), Ntanos et al. (2020), and Abdalla (2024). These confirm the importance of integrating environmental and social aspects into entrepreneurship education. In this context, the study by Al-Fattal (2024) underscores the importance of entrepreneurship education programs incorporating more comprehensive practical experiences, enhancing financial literacy, and providing psychological support to help students overcome these challenges.

Many existing models remain insufficiently explored, especially in the V4 context, where historical and economic factors are influential. Author recommendations on the perceived advantages and disadvantages of entrepreneurship (Fernández-Bedoya et al., 2023; Maalaoui et al., 2020; Thurik et al., 2024; Wiklunda et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2021; Ziemianski & Golik, 2020) are highly relevant to educational processes. Our findings indicate that previously dominant factors may no longer carry the same weight, emphasising the need for a new perspective on entrepreneurial education aligned with modern market needs.

ConclusionThis study aimed to identify significant factors influencing the entrepreneurial inclinations of university students in selected Central European countries and to present a comprehensive model explaining the relationships among those factors.

The findings support the conclusion that constructs such as state support, a favourable macroeconomic environment, and external financing opportunities play a crucial role in shaping students’ entrepreneurial ambitions. University students confirmed that higher education, state support, and suitable macroeconomic conditions positively influence their entrepreneurial attitudes. However, education, while positively evaluated, showed the least intensive effect, suggesting room for improvement in entrepreneurship-focused educational programmes. There are significant opportunities for universities to improve their approach to entrepreneurial education, especially by integrating it into broader economic and social contexts. By doing so, universities can implement educational platforms that support innovation and business growth. Strengthening entrepreneurial education can significantly influence the economic dynamics of society. A long-term vision should aim to create holistic educational approaches that integrate theory with practice, supported by collaboration between the government and the business community.

The study’s results are relevant not only academically but also for policy and management, as they highlight the important factors shaping students’ entrepreneurial tendencies and reveal gaps in the field. These results send a clear message to national policymakers: entrepreneurship education is insufficiently emphasised in Central European universities, despite its importance for long-term economic and social development. Establishing a public discourse around the importance of entrepreneurship for university graduates is necessary, as they are better placed to drive sustainable innovation and sophisticated business practices.

Limitations of this study include its regional focus on the V4 countries, which may limit generalizability to other geographical contexts. Since the research was geographically limited, it is important to acknowledge that these findings may not fully represent the entrepreneurial environments of other regions. Additionally, the quantitative research is limited by the specific cultural (e.g., strong influence of Catholic religion and traditions), economic, and institutional context (e.g., countries neighbouring Ukraine). These characteristics may pose barriers to broader generalisation. Future research should aim to eliminate such geographical constraints and examine students’ attitudes across a wider range of countries.

Future research should also focus on quantifying and comparing students’ attitudes over time and across countries. Both time-invariant and context-sensitive factors should be considered. Our findings confirm that the entrepreneurial ecosystem must evolve in response to societal and global changes. In conclusion, entrepreneurship education is a key factor in strengthening a qualitative-quantitative entrepreneurial community. Governments and universities should collaborate to create favourable conditions that encourage future entrepreneurs and ensure their long-term growth.

As patterns emerge regarding various factors influencing students’ entrepreneurial behaviour, it is important to diversify and deepen research into underexplored areas. One such area is the resilience and motivation that underlie entrepreneurial tendencies. Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches could provide richer insights. Group analyses to identify common themes among both aspiring and risk-averse students can further enhance research.

FundingThe paper is an output of the project VEGA: 1/0109/25 The theoretical model of ESG in the SME segment in the V4 countries.

Data availabilityData will be made available on request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJaroslav Belas: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Data curation. Dalia Streimikiene: Writing – original draft, Supervision, Conceptualization. Jan Dvorsky: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Formal analysis. Martina Jakubcinova: Conceptualization. Andrea Bencsik: Validation, Methodology.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to dependence the work reported in this article.