This study investigates how entrepreneurship education delivered through school cooperatives can reduce early school dropout rates and prevent the NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) phenomenon. Drawing on social capital theory, we address the following research questions: (1) What benefits do school cooperatives provide to young people involved in entrepreneurship education activities?; (2) What factors create a favorable setting for developing entrepreneurship education that can reduce the NEET phenomenon?; and (3) What is the role of local actors in promoting entrepreneurship education to contribute to transforming NEET young people into EET (in Education, Employment, or Training) people? We analyze a case in Italy with pupils aged 8–13. Data was collected from 16 in-depth interviews with educators, teachers, and social enterprise managers. We then employed reflexive thematic analysis and social network analysis to examine benefits, enabling conditions, and relationships among actors. We identify six enabling factors of entrepreneurship education. Teachers operate as brokers, linking schools, social enterprises, and community partners. School governance sustains strong ties and proximity. Institutional support, partnerships with municipalities, nonprofits, and firms, and alignment with local labor market opportunities further reinforce the educational ecosystem. We find that school cooperatives develop both bonding social capital (trust and belonging) and bridging social capital (networks and resources) that foster engagement, skills development, and pathways toward EET. The study concludes that entrepreneurship education grounded in school cooperatives mobilizes local networks to combat the risk of NEET and suggests practical priorities, including strengthening teacher brokerage and governance capacity, formalizing community partnerships, and designing education programs that cultivate both bonding and bridging social capital.

Based on an inclusive development perspective, the United Nations Agenda 2030 highlights the different aspects of poverty and the relevance of the social dimension to sustainable development, particularly focusing on younger generations (e.g., Agasisti et al., 2021). The struggle against poverty cannot be limited to filling the financial gap between different areas of the world or social groups. It requires a holistic process of inclusion that ensures that all people—regardless of their physical, mental, or cultural characteristics—can access educational, social, and healthcare services; enhance their personal and professional skills; and find a job suited to their skills to live independently and in decent conditions (e.g., Heckman & Masterov, 2007).

One of the most evident consequences of educational poverty is the so-called NEET (Not in Education, Employment, or Training) phenomenon (Mussida & Sciulli, 2023), which refers to young people aged 15–29 years who are not engaged in education, training, or employment. While the definition of NEET emerged in the 1980s (Mascherini, 2019), the problem was highlighted by the European Union as a crucial point of development programs beginning with the Europe 2020 flagship initiative Youth on the Move and the 2012–2013 Youth Opportunities Initiative (Eurofound, 2012). The COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the NEET phenomenon (Eurofound, 2021) and reinforced the need for European, national, and local prevention policies. Past research has underlined that the pandemic amplified social isolation (Norvell Gustavsson & Jonsson, 2024) and that young people have suffered serious consequences from the interruption of social contacts and their increased levels of loneliness (Bryan et al., 2024). This dramatic crisis has particularly affected vulnerable groups of young people, such as NEETs (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2021), further limiting their ability to form social relationships. However, as Morrow (1999) emphasized, building a relational context—that is, social capital (Schaefer-McDaniel, 2004)—is crucial for young people’s wellbeing and self-realization. Thus, the present study adopts social capital theory (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998) as a robust theoretical framework to understand how entrepreneurship education can contribute to preventing school dropouts and the development of NEETs by promoting an entrepreneurial mindset and skills.

To prevent the NEET phenomenon, scholars argue the importance of reducing school dropouts during adolescence and youth (De Luca et al., 2020; Khodor et al., 2024; Rahmani et al., 2024). Previous studies have highlighted the organizing role of the educational system (Kaz, 2020) and the importance of implementing innovative educational strategies to promote the engagement of young people in education, training, or employment (Mawn et al., 2017; Filges et al., 2022). The relationship between school dropouts and entrepreneurship education has been investigated mainly in the context of higher education (e.g., Åmo & Åmo, 2013; Efe, 2014; Osgood, 2012). Such research has focused on students’ intentions to develop an enterprise during or after their secondary or university degree (e.g., Åstebro et al., 2012; Isada et al., 2015; Premand et al., 2016). While a large body of literature has focused on entrepreneurial strategies in higher education and the early stage of working experience, also adopting the lens of social capital theory (e.g., Han et al., 2020; Tataw, 2023; Kamle et al., 2025; Pham, 2020; Li, 2024), less attention has been paid to the development of an entrepreneurial mindset during the first stages of education and the effect of entrepreneurship education on preventing school dropouts. Indeed, very few studies have attempted to examine the role of entrepreneurship education in combatting school dropout and the creation of the NEET populations in the earlier stages of education (Liguori et al., 2019). Investing in entrepreneurship education in primary schools is crucial for several reasons; for example, developing cross-cutting skills from an early age (McCallum et al., 2018); promoting an entrepreneurial mindset; reducing the fear of failure (Heinonen & Poikkijoki, 2006); preparing for the challenges of the labor market of the future (Gibb, 2002); and contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (Sheehan et al., 2017). Entrepreneurship education in primary schools enables young people to promote both individual success and socioeconomic progress, creating more entrepreneurs and forming responsible and creative citizens that contribute positively to society.

To fill this identified gap in knowledge, this study considers the importance of investing in entrepreneurship education by examining how entrepreneurship education prevents early school dropouts and the development of NEETs by answering the following three research questions:

RQ1. What benefits do school cooperatives provide to young people involved in entrepreneurship education activities?

RQ2. What factors create a favorable setting for developing entrepreneurship education that can reduce the NEET phenomenon?

RQ3. What is the role of local actors in promoting entrepreneurship education to contribute to transforming NEET young people into EET (in Education, Employment, or Training) people?

We conducted an exploratory study through a single case study approach, employing a mixed-method design that included thematic analysis followed by social network analysis (SNA). The case study analyzed a project entitled “Bell’Impresa!” (“Beautiful Business!” in English) that involved ten primary and secondary schools in Veneto (Italy) for three years in creating school cooperatives, which serve as an entrepreneurship education strategy involving students from primary and lower secondary schools. This case study was chosen because of the objectives of these cooperatives, which were to develop competencies in resource management, ideas, opportunities, and self-entrepreneurship to promote scholastic and professional orientation while helping prevent school dropout.

The contribution of this study is twofold. First, the findings contribute to the academic debate on the role of entrepreneurship education in promoting students’ social capital and counteracting early school dropouts, which can lead to the NEET phenomenon. The research findings reveal the role of school cooperatives as local actors involved in entrepreneurship education; the organizational factors that promote their success to reduce school dropouts and NEETs; and the relational context that supports this educational strategy, focusing on the roles of different stakeholders in promoting and managing school cooperatives. Second, the study offers some suggestions to practitioners and policymakers to avoid the growth of the NEET population by implementing innovative educational practices that promote entrepreneurship.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 examines previous literature on social capital theory, entrepreneurship education, and factors that prevent school dropouts and the NEET phenomenon. Section 3 describes the study methods and context. Sections 4 and 5, respectively, analyze and discuss the results. Section 6 presents the theoretical and practical implications, while the last section notes the study limitations and suggests further avenues of research.

Literature reviewSocial capital theoryAs stated, social capital theory serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The concept of social capital is well established in sociological and economic studies, despite the development of various definitions. Although the idea that social capital is linked to the quantity and quality of social relationships is common to all these definitions, each definition emphasizes a different aspect of this concept. For example, Bourdieu (1986) defined social capital as “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition” (p. 248). In contrast, Coleman (1988) emphasized the individual and functionalist dimension of social capital, and Putnam (1995) underlined the communitarian nature of social capital as a set of “features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit” (p. 67). The extensive body of literature in this field provides insight into the role of social capital in empowering individuals (Coleman, 1988) and communities (Putnam, 2000) to act more effectively and lead better lives. For example, Krishna (2002) linked social capital to social and economic development as a crucial enabling factor.

Given the generative and powerful effects of social capital, this concept has been extensively explored in the management field, particularly in entrepreneurship education studies. The seminal work by Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) explored the role of social capital in developing cooperative logics in firms to favor organizational advantage, while Anderson et al. (2007) highlighted that “it is through social relations, social interaction and social networks that entrepreneurship is actually carried out” (p. 265). Thus, entrepreneurship education should not neglect the powerful opportunity to create collaborative and trustworthy networks to enhance students’ propensity towards entrepreneurial skills and the development of an entrepreneurial mindset. Social capital theory argues that trust-based alliances; shared social and ethical norms; and professional connections are fundamental drivers for promoting access to resources, support, and growth opportunities.

Various scholars have explored entrepreneurship education through the theoretical lens of social capital theory. For example, Han et al. (2020) investigated which social interactions facilitate knowledge sharing among management students at a public university in the United States, while Tataw (2023) examined the teamwork of a sample of university students and the impact of the team on social capital. Kamle et al. (2025) found that engaging with diverse networks enhances students’ entrepreneurial abilities. However, all these studies focused on higher levels of education and ignored the first stages of the education path.

Some research has also addressed the potential of social capital to prevent school dropouts. The relationships that have been more extensively investigated are those of students with teachers (Croninger & Lee, 2001) and students with parents (Cemalcilar & Gökşen, 2012). Research on this topic has also been conducted in rural contexts (Byun et al., 2012). Although there is no research specifically examining social capital theory in the context of early education, social capital theory offers an excellent opportunity to analyze entrepreneurship education contexts, both methodologically (because it allows examination of the external and internal conditions for knowledge exchange and the cooperative development of skills) and in relation to content (given the consolidated role of social capital in entrepreneurial development). Thus, employing the theoretical perspective of social capital is valuable in examining how to combat the issues of school dropouts and NEET.

Entrepreneurship education and factors that prevent school dropouts and the NEET phenomenonEntrepreneurship education is a vast field of research that has been explored from various theoretical and methodological perspectives, including that of social capital theory. Scholars have examined many different aspects of entrepreneurship education. For example, entrepreneurship education influences the entrepreneurial intentions of young people to start a business by contributing to building an entrepreneurial mindset and developing positive personal attitudes toward exercising entrepreneurial behavior (Lee et al., 2006; Martínez-Gregorio et al., 2021; Adeel et al., 2023; Feola et al., 2024; Overwien et al., 2024; Chang et al., 2025). Several studies also highlighted the critical role of higher education institutions (Longva et al., 2020; Lyu et al., 2023; Thaba-Nkadimene et al., 2024), such as universities and research centers, in proposing different initiatives for entrepreneurship education. For example, these institutions have been found to stimulate students who aspire to become entrepreneurs by creating more awareness of entrepreneurial action (Walter et al., 2013) and educating them by organizing courses that enable them to develop the necessary knowledge and specific skills to start a business (Padilla-Meléndez et al., 2014). Some of these institutions act as incubators by providing (technical, human, professional, and financial) support to start-up teams (Marchand & Hermens, 2015). Recent studies have demonstrated that according to the triple helix model of innovation, the involvement of universities, government, and businesses stimulates students’ entrepreneurial intention to engage in start-up activities (e.g., Feola et al., 2019). Helping students launch successful start-ups requires considering various contributions that, when combined, form an ecosystem comprising universities, accelerators, entrepreneurs, supporting actors, and investors (Wright et al., 2017).

Some research has examined the need for entrepreneurship education at university (Tang et al., 2014), revealing that practice-oriented education with engaging teaching methods (Colombelli et al., 2022), such as e-learning (Widjaja et al., 2022) and courses taught by lecturers who are experienced entrepreneurs (Zotov et al., 2019), are most beneficial in promoting students’ future entrepreneurship activities.

Other studies have highlighted the importance of organizing courses on social entrepreneurship to increase students’ propensity to create social enterprises (Hockerts, 2018). However, their development is limited by low level of social entrepreneurship knowledge and reduced access to human capital and financial resources (Rahman et al., 2019). In addition, financial literacy has been found to positively affect entrepreneurial intentions among college students (Tran et al., 2024).

Further, decision of students to pursue entrepreneurship is significantly influenced by access to finance (Saoula et al., 2024). Research by Rusu et al. (2022) indicates that support from family and friends positively affects young people’s entrepreneurial intentions, and Ghiță-Mitrescu and Antohi (2023) emphasized a preference among aspiring entrepreneurs for nonreimbursable financing. In this context, crowdfunding can be important because it fosters knowledge sharing and collaboration among various stakeholders (Presenza et al., 2019; Logue and Grimes, 2022) and can implement match-funding schemes that enhance local decision-making processes (Loots et al., 2023). In Italy, banking foundations are pivotal in the funding process, having allocated 11 % of their total funding—1047.5 million euros—to education and training initiatives (Associazione di Fondazioni e Casse di Risparmio, 2023, p. 12). Such foundations fulfill a dual role by supporting social initiatives and promoting skill transfers, similar to the strategic approach of private equity funds (Boesso et al., 2023).

As stated, less research attention has been paid to entrepreneurship education in primary/elementary and secondary schools. However, previous studies have outlined the importance of introducing entrepreneurship education in national education systems (e.g., Gorenc et al., 2023); examined programs organized by educational institutions to improve the employability of their learners (e.g., Nchu et al., 2015); and highlighted the need to train teachers in the delivery of entrepreneurship education (e.g., Enombo et al., 2015).

In summary, previous research has highlighted the importance of providing entrepreneurship education starting from earlier education through appropriate teaching and content delivery, and with the support of family, the sociocultural environment, and business development programs (Ellikkal & Rajamohan, 2023).

Given the importance of entrepreneurship education in the education system and the limited understanding of its influence in schools, this study seeks to address the existing gap in knowledge by investigating methods of fostering the entrepreneurial spirit in primary school students and thereby contributing to the prevention of NEET populations.

The acronym NEET was first introduced in the late 1980s by the government of the United Kingdom and was later adopted across European countries to refer to people aged 15–29 (Mascherini, 2019) who were not engaged in any form of education, employment, or training. Subsequently, the term developed a broader meaning to include different categories of individuals, and the compulsory school age of different countries also influences the definition of this term. For example, Yates and Payne (2006) proposed a classification of NEETs that consists of three subgroups: (1) “transitional NEET” (i.e., those who are temporarily NEET because of individual circumstances but who can be readily re-engaged in employment, education, or training); (2) “young parents NEET” (i.e., those who decide to quit work, or leave school or training to take care of their children); and (3) “complicated NEET” (i.e., NEET young people who also exhibit several “risk factors” in their lives such as being homeless, engaging in criminal behavior, or having emotional/behavioral problems). People in the third subgroup suffer from “social exclusion” or a “hazy future” (a term used by Ball et al., 1999) because these NEETs have no definitive aspirations and are generally labeled by society as “complicated.” The debate on the appropriateness of the term is still of current interest, and it has been claimed that the extension of the usage of this term has not been accompanied by an increase in knowledge and understanding about the composition and needs of this vast and diverse group of people (Maguire, 2015). There is a large degree of heterogeneity within NEET populations, and policymakers must be conscious of this to define tailored policies accordingly (Redmond & McFadden, 2023).

The topic of NEET young people has been addressed in various research fields, but mainly in social sciences (e.g., De Luca et al., 2020); education (Lőrinc et al., 2020); psychiatry (e.g., Gariepy et al., 2022); public environmental occupational health (e.g., Kingsbury et al., 2025); sociology (Manzoni & Gebel, 2024); and economics (Mussida & Sciulli, 2024). Studies that examine NEET and entrepreneurship are scant (e.g., Zhartay et al., 2020).

Entrepreneurship education has been found to be one of the factors that contribute to decreasing the percentage of NEET young people (e.g., Antohi & Ghiță-Mitrescu, 2022) through developing the inclination of young people towards entrepreneurial initiatives through the enrichment of their knowledge and skills (Fayolle & Gailly, 2015). Entrepreneurship education can help children develop competencies that are valuable twenty-first-century skills, such as critical thinking, creativity, innovativeness, initiative-taking, cooperation, teamwork, and problem-solving—that are crucial to personal and professional success in an increasingly complex and dynamic world (McCallum et al., 2018). The factors that connect NEET young people and entrepreneurship education have been investigated in the past decade by both policymakers and researchers. For example, international institutions such as the OECD or the European Union have examined educational and occupational policies implemented in various countries (e.g., Maguire, 2015) that have introduced entrepreneurship-based programs targeted to NEETs to guide them toward career paths of self-employment and business creation (e.g., Santos-Ortega et al., 2021). However, very few studies have been conducted on entrepreneurship education among NEET populations. Hazenberg et al. (2014) examined the outcome performance of work-integration social enterprises and a for-profit work-integration organization providing employment enhancement programs to NEETs. Their research revealed no significant difference in outcome performance between these organizations. Volkan (2022) proposed a support model of social entrepreneurship for youth in Turkey—a model that can be valuable tool against youth unemployment in developing countries—by highlighting the importance of training programs for NEET youths and suggesting giving financial and consultancy support to those who successfully complete training.

Public social spending plays a critical role in supporting programs aimed at addressing the needs of NEETs. A recent study by Youn and Kang (2023) indicates that increasing public social spending of educational programs can significantly reduce the risk of young people becoming NEET and particularly benefits those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds. The study emphasizes the importance of public expenditure on school-to-work transitions and labor-market initiatives, particularly for young people with lower educational levels; those with parents have limited educational attainment; and females (Youn & Kang, 2023, p. 11). However, budget constraints often restrict interventions from being targeted to specific groups within the broader population (Maguire, 2015).

Some studies have focused on the relationship between early school dropouts and NEET. School dropout has been described as the consequence of young people’s progressive disengagement from school (Ryan et al., 2019). De Luca et al. (2020) analyzed how early school dropouts negatively affect individuals by increasing their probability of becoming NEET in Spain and Italy. Specifically, in Italy, approximately 70 % of women and 45 % of men who are early school leavers become NEETs, demonstrating the influence of early school dropout on NEET. These findings suggest investing more in education to reduce early dropout rates and, therefore, NEET subsequently. Research indicates that certain situations can significantly enhance student engagement in traditional schools and second-chance education programs (Portela Pruaño et al., 2022a, 2022b). Some scholars suggest that integrating theoretical education with education on how to manage real-world challenges and experiences can motivate students effectively, particularly those who do not thrive in conventional teaching contexts (Filges et al., 2022). In such a context, entrepreneurship education can be a valuable tool to address the NEET phenomenon by engaging young individuals, reducing early school dropout rates, and equipping students with practical skills for their entrepreneurial pursuits. Additionally, some researchers advocate for “accelerator interventions” as a strategy to improve retention rates, involving a co-financing approach and the simultaneous management of multiple Sustainable Development Goals (Desmond et al., 2024, p. 169).

Research examining the dynamics of the complex NEET phenomenon has investigated the potential relationship between social capital development, specifically trust and social networks. Marques et al. (2025) emphasized the importance of ongoing local and regional efforts to unite partners, stakeholders, and beneficiaries around shared objectives to foster social capital. NEET young people particularly benefit from social inclusion programs that engage a broader range of participants beyond conventional education and training systems (Marques et al., 2025). Additionally, a study that analyzed data from 103 Italian provinces argues that social capital plays a crucial role as a “putative protective factor for NEET” youth (Ripamonti & Barberis, 2021, p. 13), particularly in Northern Italy, where the influences of economic and cultural capital appear to be less significant. Finally, research has also demonstrated that social capital tied to family dynamics—primarily assessed through family structure and the quality of parent–child communication—plays a crucial role in facilitating a successful transition from school to the workforce (Broschinski et al., 2022).

MethodologyResearch designThis research employs a case study (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Corbin & Strauss, 2015) and adopts an exploratory research design (Yin, 2017) through a mixed-method approach. Specifically, the study employs qualitative—reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) based on asynchronous email interviews—and quantitative (SNA) methods to provide in-depth data on the network fostering entrepreneurship education, which cannot be fully explained by quantitative statistics alone (e.g., Altissimo, 2016).

Considering that the topic of entrepreneurship education as a strategy to reduce early school dropout ratest and prevent NEET development is still an emerging phenomenon that has received limited attention in entrepreneurship literature, the use of a case study was considered appropriate to address the research questions and facilitate an in-depth analysis of the phenomenon in its real-world context (Eisenhardt, 1989; Woodside & Wilson, 2003). Despite the research limitations of using a single case study, this approach is considered acceptable when the case is “unusually revelatory,” “extremely exemplary,” or allows researchers to access unusual information (Yin, 2009; Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). The case study selected for this research (i.e., Bell’Impresa!) was chosen for its relevance and characteristics that can be used to generate insights that are valuable to other similar initiatives.

To examine the impact of entrepreneurship education on reducing school dropout rates and NEETs (RQ1) and to identify the factors that create a favorable setting for developing entrepreneurship education (RQ2), we conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews (via the asynchronous email approach) with members of the Bell’Impresa! project and analyzed the resulting data using RTA (Braun & Clarke, 2012).

To assess the role of local actors in promoting entrepreneurship education (RQ3), a quantitative approach based on SNA across the participants of the Bell’Impresa! project was used. SNA is an appropriate research method for analyzing social relationships from the perspective of social capital theory (e.g., Abbasi et al., 2014). A social network is a collection of social actors (nodes) and their relationships. SNA is a suitable method for analyzing network data because it enables the investigation of social structures using theoretical concepts and techniques based on graph theories (e.g., Otte & Russeau, 2002; Prell, 2012). Generally, relationships or interactions (i.e., ties) that connect actors, people, stakeholders, or groups (i.e., nodes) of the network are graphically represented within visual maps (Scott & Carrington, 2011). For this study, the nodes are the local actors who have contributed to realizing the entrepreneurship education project within the network as designers or managers.

Context of the studyThis study focuses on a case study in Italy, which has one of the largest NEET populations in the European Union. It considers NEET to represent young people who are not employed or in education or training of a broader age range (15–34 years) than that of the European Union. According to Eurostat (2021), in 2020, the Italian NEET population (25.1 %) was 7.5 % higher than the European average (17.6 %), remaining constant at over 20 % over the past five years (Statista, 2021). To face this “lost generation” (as Mario Draghi, past President of the European Central Bank, defined this part of the population in 2016), in 2022, the Italian government adopted a NEET plan (i.e., policy brief formalized by a joint youth labor-policy decree), whose purpose is to reduce the number of NEET population present in Italy, which is >3 million people, the majority of whom are women (1.7 million).

In Italy, young people are required to attend school for 10 years, from the ages of 6 to 16, pursuant to Law No 296 of 27 December 2006. After that age, school attendance or the option of vocational training or work is optional, and therefore, from that age onwards, the NEET phenomenon fully develops. Nonetheless, the antecedents of the problem can be detected before young people are 16 years old, during the lower levels of school.

Among the different educational strategies adopted to prevent school dropouts, the present study explores entrepreneurship education implemented through school cooperatives, which are educational methods designed to promote student entrepreneurship to benefit children and young people as well as the social and economic context in which these programs are delivered. These educational programs are designed to promote students’ personal skills, mainly entrepreneurship. However, they are also considered an effective strategy for enhancing students’ engagement in their school experience and avoiding early dropouts (e.g., Girelli et al., 2021).

As stated, this study analyzes the Bell’Impresa! project, which was proposed and is managed by a consortium of not-for profit organizations with the coordination of Cooperativa Sociale Hermete, a social enterprise mainly devoted to educational services. The program design was based on previous experiences of school cooperative programs managed by the same consortium of not-for-profit organizations and social enterprises involved in Bell’Impresa!, and involved the support of public educational services. Bell’Impresa! was financed by “Con I Bambini,” a social enterprise that operates to combat child educational poverty, which since its launch, has supported 687 projects with >425 million euros. “Con I Bambini” operates through the financial support of Italian banking foundations that created a specific fund for this enterprise as well as through its many partnerships with public and private organizations, such as associations, social cooperatives, schools, universities, research institutions, and local public administrations (Associazione di Fondazioni e Casse di Risparmio, 2023, p. 235).

The aims of the program were to promote entrepreneurial spirit within families, at school, and within the wider educational community; that is, to foster an attitude of personal responsibility, proactiveness, creativity, and initiative among children aged 8 to 13 and their communities. Specifically, the initiative aimed to foster positive social relationships through business simulation activities and “productive branches” (e.g., play workshops, cooperative labs, entrepreneurial projects, guidance programs, residential summer camps, and production of communication materials) in both school and extracurricular settings.

The Bell’Impresa! project was implemented in 10 (primary and secondary) schools located in the province of Verona (Northern Italy). Twenty-five school cooperatives were founded, involving 542 students and supported by 119 teachers. Furthermore, the program conducted 32 meetings with parents and 40 with local partners.

Sampling procedureWe conducted preliminary analysis of secondary data collected from the program website, institutional documentation, and through direct contact with the social enterprise leader of the program (Cooperativa Sociale Hermete) to identify all the organizations that participated in the program. These actors were then contacted via email, informed about the aim of the study, and asked to find available participants for the interview questionnaire among their members who were directly involved in the project. All the people contacted agreed to collaborate and identified relevant respondents who accepted the invitation. These individuals were sent an email explaining the aim of the study and were asked to complete a semi-structured questionnaire created on the LimeSurvey platform. Respondents were ensured anonymity and confidentiality. To involve participants who were centrally embedded network actors due to their role as elite informants (Aguinis & Solarino, 2019), a nominal criterion was employed (i.e., only those who formally occupied a design or management role in the network were interviewed).

Overall, 16 responses were obtained from members of different organizations involved in the program, including local organizations, public education service organizations, social enterprises, schools, and local organizations, as summarized in Table 1.

The respondents’ profile.

We used the asynchronous email interview approach for data collection because this method allows participants to respond in their preferred environment, at a convenient time, and to reflect on the answers before submitting them (Meho, 2006). The questionnaire was developed based on our literature review. It included closed and open-ended questions that focused on the following areas: (a) the intended impact of entrepreneurship education by school cooperatives on school dropout prevention and reduction (RQ1); and (b) the factors facilitating or hindering social cooperatives in promoting entrepreneurship education (RQ2). Participants were also asked if they agreed to leave their contact details for possible follow-up questions.

The interviews were analyzed through RTA, which consists of a subjective and recursive coding process that allows researchers to gain a deep understanding of the data (Braun & Clarke, 2021a). As recommended by Braun and Clarke (2012), a six-step approach was adopted. The first phase included familiarization with the data (i.e., carefully reading the responses and taking notes on data that were particularly relevant to the aim of the study). The second phase consisted of data coding and identifying recurrent topics, while the third phase generated the initial themes. The themes were reviewed and developed in the fourth phase. In the fifth phase, the themes were defined and named using an abductive approach, moving iteratively between the data and the theory (Dubois & Gadde, 2014). The sixth and final phase involved the presentation of the results.

Thematic analysis includes a variety of approaches with different characteristics (Braun & Clarke, 2021a). In RTA, reliability and validity are approached differently from more positivist “coding reliability” forms of thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2021b). Furthermore, in RTA, reliability is not about demonstrating consistency between coders given that the themes derive from recursive and interpretive procedures in which the subjectivity of the researcher(s) plays a key role.

Braun and Clarke (2025) emphasized the importance of the quality of research and frame rigor as methodological congruence and reflexive openness or transparency. We ensured quality through clear documentation of analysis, changes, and reflections in a reflexive journal, ensuring we kept records of how the analysis proceeded through the six phases. Rigor was ensured by maintaining iterative engagement with the dataset, ensuring themes were internally coherent and distinct, as well as by maintaining track of codes, evolving theme maps, memos, and drafts to track the transformation from raw data to final themes. The final themes do not “emerge” from the data but are rather “produced at the intersection of the researcher’s theoretical assumptions, their analytic resources and skill, and the data themselves” (Braun & Clarke, 2019, p. 594).

We present the findings in narrative form by providing selected extracts from the interview texts to ground themes in participants’ experiences, ensuring that each theme is organized around a clear central concept and that the thematic story was logically connected to our research questions (RQ1: What benefits do school cooperatives provide to young people involved in entrepreneurship education activities?; and RQ2: What factors create a favorable setting for developing entrepreneurship education that can reduce this phenomenon?)

Study 2We developed the second study based on SNA through consideration of the data collected from the 16 interviewees who formally occupied a design or management role in the network (RQ3). Specifically, we used the name generator technique to map the existing network. This technique was chosen because it allows the collection of relational data from all network actors. After obtaining information about the categories of actors involved in the entrepreneurship education project through the social network section of the questionnaire we created, each interviewee was asked to respond to the following questions: (1) “Please indicate with which actors in the network you collaborate to develop entrepreneurship education”; and (2) “Please indicate with which actors in the network you think it would be appropriate to collaborate in the future to develop entrepreneurship education.” The first question aimed to investigate the existing network of relationships across actors, while the second question aimed to examine the expected network that could be developed across actors to foster better entrepreneurship education. We used a roster method to gain a clear vision of the design of the expected network (Scott & Carrington, 2011). The complete list (roster) of the actors was presented in bullet point form to the respondents, who were asked to rate each relationship on a five-point scale based on the importance of the actors’ role in developing networks to foster entrepreneurship education. The list of actors was created based on the analysis of the results from Study 1. Specifically, the categories of actors were traced from the interviews, assigning a frequency to each quote. In Study 2, only the actors with a frequency equal to or higher than three were included in the list and therefore considered for the analysis.

Relational data collected through the social network questionnaire was elaborated differently based on the objectives under investigation. To analyze the existing network, data were entered into the adjacency matrix, namely the case*case matrix. It is a square (n*n) matrix, where n is the number of actors in the network, and the cells contain the data on the link between two actors. Next, the adjacency matrix was imported into the UCINET software (Borgatti et al., 2002) to examine the network structure and dynamics.

For the expected network, a bipartite network originated from a rectangular matrix of cases (actors involved in network creation in relation to design or management) for events (actors who would be involved in the network fostering entrepreneurship education). Using the UCINET software, the expected network structure and dynamics were examined.

In both analyses, the matrices of multi-value adjacencies were constructed to express the presence/absence, direction, and intensity of the relationships. Here, the integers were used to indicate the intensity of the relationships between the actors: higher values represented stronger relationship intensity, and lower values represented weaker relationship intensity.

The SNA metrics used in both analyses included the number of nodes; number of connections; network density (which reflects how connected the network is relative to the maximum possible connections, calculated by comparing the number of actual ties to the maximum number of possible ties); and community structures. To identify the most influential actors within the network, individual-level centrality measures were computed because they describe the role or position of a single actor within the network. To achieve this identification, we measured degree centrality (which reflects the number of direct connections a node has); betweenness centrality (which reflects how often a node lies on the shortest paths between others); and closeness centrality (which reflects how quickly a node can reach all other nodes in the network).

FindingsThis section first presents the results from the thematic analysis of the contribution of school cooperatives as essential actors involved in entrepreneurship education to reduce school dropouts and the development of NEETs (RQ1) and the factors that foster entrepreneurship education to reduce the NEET phenomenon (RQ2). Each theme is supported by quotations from the interviews that exemplify the shared meaning underpinning the theme and reflect the diversity of perspectives across participants. Quotations are integrated into the analytic narrative to illustrate how the interpretations are “grounded in the data” and to make transparent the evidential basis of each claim (Braun and Clarke, 2021, p. 6).

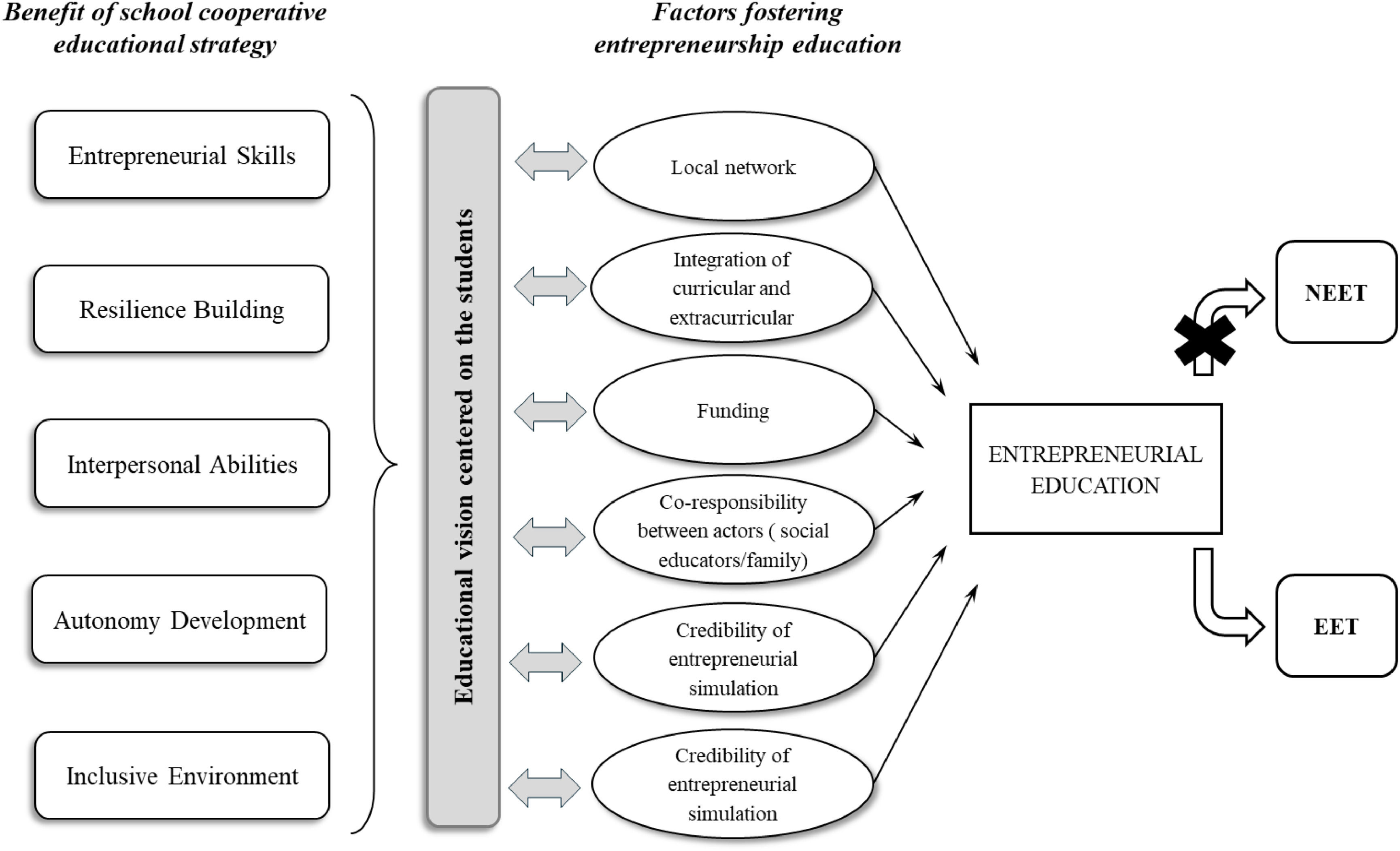

Fig. 1 illustrates the significant benefits entrepreneurship education offers young people and highlights the multiple factors that align with a student-focused educational vision.

Subsequently, the relationships among local actors within the local network, identified as a key element in promoting the development of entrepreneurship education, are analyzed using the SNA method.

Benefits for young people involved in entrepreneurship education activities organized by school cooperativesTo respond to RQ1, we employed RTA to identify the opportunities offered to young people by school cooperatives and organized them in five themes: entrepreneurial skills, autonomy development, interpersonal abilities, resilience building, and inclusive environment.

First, founding and managing a cooperative enterprise allows students to face concrete problems and develop entrepreneurial skills such as problem-solving or creativity: School cooperatives promote an experiential learning model based on “learning by doing” and business simulations. Students develop transversal skills such as initiative, creativity, time management, teamwork, and problem-solving through involvement in real activities (e.g., carpentry, redevelopment of public spaces, and production of useful objects). (R6)

Although the organizational design of a school cooperative is simple, students can experiment with the different aspects of entrepreneurship, such as the choice of the product or service they want to deliver; the structure of the governance; or how to finance their enterprise. Consequently, their minds are opened to the multifaced system of competencies typical of real entrepreneurs and managers: The school cooperative allows students to acquire skills in management, organization, and creative and manual aspects. (R11) Thanks to the simulation of a real cooperative and the planning actions implemented to plan the coop’s activities and raise funds. (R9)

Second, school cooperatives promote students’ autonomy development, such as self-analysis and making decisions in a complex context, thus facilitating their autonomy in orienting their life projects without being negatively influenced by other people’s decisions: Students are allowed space for choice, responsibility, and freedom, accompanied by moments of comparison and reflection. (R13) School cooperatives are potent tools for orientation and discovering one’s aptitudes. In the educational path, strategic pre-work and work skills for one’s future are tested. (R15)

School cooperatives engage students and adults in an intergenerational relationship that develops mutual trust and enables students to make autonomous decisions: They allow kids to choose and act autonomously, making them acquire responsibility. [In most contexts, they] have few opportunities to experience the opportunities and challenges that come with making project choices; often, adults intervene without leaving room for discovery and error. (R2)

Third, school cooperatives’ entrepreneurship education requires students’ interpersonal abilities, including mutual recognition of the skills of oneself and of other, as well as the ability to have an overall vision of problems. Teamwork skills help students face complex issues and contexts similar to those they will find in higher levels of education or the real-life work context: School cooperatives guide children to make frequent decisions consciously. They represent one of the few opportunities for students to define a project to be realized collectively. They face the need to analyze the project’s feasibility based on available resources, which forces them to differentiate roles and tasks. This is achieved not by imposing adult roles, but by considering the strengths of the group members. (R5)

The need to find a professional placement within the simulated cooperative enterprise pushes students to develop an awareness of their own skills and those of others: School cooperatives allow everyone to participate using their skills. They make them feel they have value and that they can make their contribution. The activation of each person’s skills is an element that pushes them towards the awareness of their potential, and also to improve in the “difficult” and critical moments of life. (R1)

Fourth, experiencing cooperative entrepreneurship during their time at school helps students’ resilience building through learning how to accept the possibility of making mistakes, learn from them, and find individual or collective solutions. From the experience of simulated failure, students understand the nonlinearity of entrepreneurial (and personal) development paths and strengthen their resilience: [Participating in cooperatives gives] children and young people the opportunity to test themselves, even to be able to “make mistakes” in a protected and controlled way. (R10)

Fifth, entrepreneurship education activities organized by school cooperatives lay the groundwork for developing inclusive environments. These initiatives provide vulnerable students who find participating in traditional teaching activities challenging with new opportunities to engage and express their potential: The active participation of all allows working effectively, both with “excellent” students and with “fragile” students and/or with “educational poverty.” The inclusion of all in a common project and the enthusiasm for its realization are certainly important factors in preventing the phenomenon of school dropout. (R12)

To respond to RQ2, we employed RTA to identify the organizational factors that foster the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education initiatives in preventing early school dropouts and avoiding the NEET phenomenon. First, we highlight a student-focused educational vision as a cross-cutting prerequisite of organizational factors. That is, entrepreneurship education works if it is rooted in a clear educational vision centered on students and on the development of their life project: Administrative, financial, and even cultural challenges can be overcome when people believe in the project. The difference arises when teaching becomes normal in a way that makes the student the central figure, helping them view school as a place that values them and supports their growth, fostering a vision of the community and its key players as allies in their development. (R1) Another factor influencing the experience is whether the school supports cooperatives’ “parallel” work. This involves considering children and young people as growing individuals who need diverse stimuli to discover themselves, learn, and find their path. (R4)

In addition to this prerequisite factor, we identified six major themes, each of which refers to an organizational factor. The first organizational factor we identified in related to the creation of a broad and cohesive local network around the school that involves several stakeholders who can contribute to different competencies and provide opportunities for developing the entrepreneurial ideas of students: The connection with the local community: when students have opportunities and visibility beyond the school context, it strengthens their motivation and sense of belonging. (R2) Collaboration with local services and institutions enhances the impact and support of the students’ activities, recognizing their demonstrated skills. (R3) When the community responds to the cooperative’s initiatives truthfully and meaningfully or stimulates the cooperative with relevant requests and relationships, positive conditions are created. (R8)

A second crucial factor is related to the integration of curricular and extracurricular activities in a unitary educational project. The creation of a simulated student cooperative enterprise is more effective in developing skills if it opens the educational environment and provides new opportunities for nonformal learning: The opportunity to simulate a cooperative using an experiential method within a protected environment allows students to experiment with guidance and support from adults. (R11)

Implementing school cooperatives as a strategy for entrepreneurship education and reducing the risk of dropout is time-consuming and requires human, infrastructural, and financial resources in addition to the essential equipment of the school system. For this reason, the third crucial organizational factor is funding. Two pivotal roles are played in raising and managing financial resources: the provider of financial resources (e.g., private or banking foundations) and the project’s designer, who acts as a hub for the engaged players. The role of funding is highly strategically important: One cannot ignore the fact that a school cooperative requires resources (primarily the time of social educators and planning efforts). Thus, it is crucial to establish connections with financial entities (foundations or other organizations) to build stable partnerships that support school cooperatives over time. (R14)

One respondent identified lack of funding as an obstacle to the project’s development: The difficulty in finding funding entities often poses a significant obstacle to the success and sustainability of school cooperatives. (R4)

The fourth factor is the co-responsibility between actors (e.g., social educators, teachers, families, and local institutions) that occurs through engaging in the cooperative logics of the educational community in the delivery of entrepreneurship education. Collaboration between different actors means that entrepreneurship education does not have to be limited to the time devoted to the simulated cooperative, but can also be delivered through different formal and informal activities: The commitment of school leaders to the project must go beyond formal endorsement, requiring daily collaboration with and among teachers. This includes integrating innovative methodologies (such as business simulation and service-learning) into teaching. It also involves engaging families and the local community in the projects. (R6) By itself, a school cooperative is merely a tool, and its potential remains untapped unless it is integrated into a broader educational framework involving various stakeholders from the educational community (teachers, the school institution, and families). (R14)

In one interviewee’s opinion, cooperation is needed not only in the operative phases of the project but also in its design: Conversely, the absence of teachers in the cooperative’s development team limits the project’s potential. (R15)

The fifth factor is the importance of the credibility of entrepreneurial simulation, which allows students to experience real-life situations: The accuracy in structuring and managing the cooperative model within the target group is essential. A “real” connection with the local community (e.g., external clients and real suppliers) enhances the project’s effectiveness. (R15)

Teachers and social educators may have to rely on other stakeholders to create realistic business simulations. For this reason, one of the respondents notes how the contribution of skills and experience offered by external actors (e.g., managers and entrepreneurs who provide help in designing and developing the ideas of student businesses) is fundamental: The credibility of the cooperative as a “simulated enterprise”: depends on this realism, supported by contacts with local entities, particularly businesses, and entrepreneurs, who can act as mentors, tutors, or even funders of the initiative. (R14)

The sixth factor is the need for critical analysis of the experience. In the early stages of their education, students need to be helped to develop a consciousness of their competencies, and this consciousness can be fostered by entrepreneurial experience. Without this reflective phase, the dispersion of experience is a concrete risk among the many contradictory stimuli that young people often receive: An additional important element is initiating reflection and meta-reflection on the actions and learning experiences within the cooperative activities. (R4)

This subsection of the research responds to RQ3 by explicitly discussing the local network that fosters entrepreneurship education and examining the structure of this network and the role of the network’s actors. The results of this study from the application of SNA reveal that the local network is composed of five nodes, which are the five actors involved in the project: local organizations, public education service organizations, school governance, social enterprises, and teachers, and these are joined through 15 ties (Fig. 2).

This network presents a high-density value (0.75), which measures the proportion of connections present versus the maximum possible number of connections in a network. Precisely, 75 % of the possible ties in the network are present. These data suggest the existence of a highly interconnected network, with most actors having a direct relationship with other actors. Given that no node in the network presents only one connection (all actors have at least two connections), there are no pendant actors within the network. In addition, no actor is wholly disconnected from the network; thus, there are no isolated actors.

One only community forms this network given that the connections between and among actors do not form distinct and autonomous clusters/subgroups. This emerges from the negative value of network modularity (−0.028), which indicates how the network forms a single, cohesive structure, where ties are evenly distributed across actors, and no well-defined communities are present.

Table 2 proposes the centrality metrics of the local network from which it is possible to identify the network’s structure and the role of individual nodes.

Centrality metrics of the local network.

In the network, teachers have the highest degree centrality (2.0), demonstrating that they are the most connected nodes in the network and the most active, both for incoming and outgoing relationships. Teachers are followed by public education service organizations, school governance, and social enterprises, which present intermediate values (1.5). Local organizations have the lowest value (1.0), indicating their marginal role compared with the other actors.

Teachers and school governance have the highest value of in-degree centrality (4), demonstrating that they receive more connections than others; accordingly, they are perceived as key actors. Teachers also have the maximum value of out-degree centrality (4), demonstrating that they send most connections. School governance has the lowest value (2), indicating a lower activity as an information transmitter.

Although the network is strongly connected without clearly defined subgroups, this network has some liaison actors (i.e., actors that act as bridges between and among different groups in the network) that facilitate the flow of information or resources. Teachers have the highest betweenness centrality value (about 0.319), demonstrating that they act as key liaison actors, connecting other actors and acting as a critical bridge for information flow. In contrast, public education service organizations (about 0.042); school governance (about 0.028); and social enterprises (about 0.028) play a minor but significant role as liaison actors. Local organizations have no bridge role in the network (their value is 0).

Teachers and school governance have the highest value of closeness centrality (1.0), demonstrating that they are the nodes closest to all others and, therefore, their role is strategic for quickly reaching all other network actors and rapidly disseminating information or resources. In contrast, local organizations have the lowest value (about 0.571), suggesting they have a more distant and less integrated role in the network.

Teachers emerge from this analysis as actors playing a central and dominant role in fostering entrepreneurship education in the network because they also have the most connections overall. They are defined as egocentric actors because they determine the possibility of potentially influencing the flow of information and relationships between and among different parts of the network. This egocentric position is determined by the high degree centrality (i.e., the node has many direct connections) and the high betweenness centrality (i.e., the node controls many key connections in the network). Based on the high number of connections in the network, the teachers also emerge as star actors. Their role is determined by the high degree centrality (i.e., this node is significantly more connected with many direct connections than are the other nodes) and the dominating interactions with other actors.

Using a predefined list, the five actors involved in the project were also asked to identify those who could contribute to the development of entrepreneurship education, thus creating a hypothetical network that could be realized in the future. The analysis conducted reveals that this expected network consists of ten nodes (specifically, families, firms, granters, local organizations, public education service organizations, network design, network management, school governance, social enterprises, and teachers), joined by 13 ties (Fig. 3).

The network has a very high density (0.8125) because almost all nodes are connected to many others: network management is a particularly dominant node that acts as a hub in connection with many other nodes, and there are other nodes with limited connections.

Network management is also a node that is fundamental to maintaining the network’s connectivity: if it were removed, it would fragment the network into disconnected subgroups. Therefore, it is called a “cutpoint” node. Firms, granters, and local organizations, which are pendant actors because they have only one connection in the network, are connected to network management.

There are no isolated nodes, given that each node is connected to at least one other node, contributing to the cohesion of the network.

Table 3 proposes the centrality metrics of the expected local network. In-degree and out-degree centralities are not proposed in this table because any direction toward individual actors is possible in an undirected graph, as seen in Fig. 3, where it is assumed that the connections are reciprocal.

Centrality metrics of the expected local network.

Network management has the highest degree centrality (about 0.889), being directly connected to almost all other nodes and playing a significant role in the network. Network design plays an important but less central role than network management does, with an intermediate degree centrality value (approximately 0.556) given that it connects to more than half of the nodes. Families, public education service organizations, school management, social enterprises, and teachers have a low degree centrality (about 0.222), indicating their limited influence in the network. The other actors (firms, granters, and local organizations) are less central and have little impact on the different actors in the network.

The betweenness centrality analysis suggests that network management is the leading liaison actor (approximately 0.722), connecting nodes otherwise weakly connected, such as firms, granters, and local organizations. Network design has an intermediate betweenness centrality (approximately 0.139), which refers to nodes that contribute to the network as a middleware in some connections but are not critical. That is, network design is essential for connecting some nodes, but the network remains connected even without it.

Network management is not only a key intermediary but, based on its closeness centrality (0.9), it is also the most accessible and integrated node in the network.

DiscussionThe findings of this study provide fresh insights into the role of school cooperatives as vehicles for entrepreneurship education aimed at preventing early school leaving and reducing the incidence of NEETs. By focusing on primary and secondary schools, the study extends prior research that largely concentrated on higher education or interventions for already disengaged youth. The results demonstrate that entrepreneurial education can serve as an early preventive mechanism, suggesting that policies to counter dropout and NEET risks should integrate cooperative-based initiatives at earlier stages of the educational system. This evidence confirms previous pioneering research showing that school cooperatives foster collaboration and inclusion (Girelli et al., 2021) and contribute to avoiding individualism in schools (Zimnoch, 2018). In particular, the creation of school cooperatives in the early years strengthens students’ social capital, allowing them to participate in inclusive networks of trust, reciprocity, and collaboration (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000). The findings deepen the existing studies on the relationship between educational strategies, soft skills seasoning, and social capital accumulation by analyzing the school cooperative educational strategy as a facilitator of relational competencies. These relational resources support the development of autonomy, resilience, interpersonal skills, and inclusion, which act as protective factors against school dropouts. This extends prior research linking social capital to educational attainment and youth transitions by providing evidence at earlier stages of education.

In addressing RQ1, this study also highlights that entrepreneurship education delivered through cooperatives generates broad developmental benefits that go beyond entrepreneurial intentions or business creation. Students develop transversal skills such as teamwork, problem solving, and creativity, as well as resilience, decision-making ability, and social inclusion. This highlights entrepreneurship education as a comprehensive educational tool that supports students’ life projects, particularly those who struggle to follow traditional school curricula. In this sense, cooperative-based entrepreneurship education contributes to the development of personal competencies (Singh et al., 2020) that are applicable throughout schooling and beyond.

In addressing RQ2, the study revealed that entrepreneurial initiatives alone are insufficient unless supported by crucial organizational factors: a student-centered educational vision, stable funding, integration of curricular and extracurricular activities, co-responsibility among actors, credibility of the simulation, and, especially, the quality of the local network (the actors involved and their relationships). This reinforces and specifies what the literature has only broadly suggested in general terms; namely, that social networks and local collaborations are central to the success of such initiatives. The original contribution of this research work is the concrete mapping through SNA of the network structure, the most central nodes (teachers and school governance)—a delineation that aligns with the results of Hardie et al. (2022), who highlighted the importance of school leadership in developing entrepreneurship education programs—and the potential nodes to be further developed (network management, families, funding bodies). In the light of social capital theory, the analysis also highlights the importance of local networks in developing school cooperatives, consistent with Thomassen et al. (2020), who stressed the role of context, and with Thomas (2023), who underlined the need for broad partnerships. The study further confirms that access to finance in the form of a broader group of investors engaged in long-term relationships is also critical for successful entrepreneurship education—a finding that supports previous research results (Wright et al., 2017; Rusu et al., 2022; Saoula et al., 2024). In this context, banking foundations are acknowledged as highly relevant financial partners, engaging in strategic philanthropy through private equity funds (Boesso et al., 2023) that support the delivery of entrepreneurship education.

In addressing RQ3, the SNA revealed that teachers are pivotal bridging actors, coordinating and connecting different stakeholders in the network. They act as key intermediaries who facilitate interaction, a role consistent with prior research on teacher networks in fostering entrepreneurial culture (Wraae et al., 2021; Wasim et al., 2024), effective educational programs (Syed et al., 2024) and cross-cutting entrepreneurship skills, such as critical thinking, creativity, and teamwork among students (e.g., Joensuu-Salo et al., 2021; Machali et al., 2021). School governance was found to be another critical network actor fostering entrepreneurship education, as also identified in previous studies (e.g., Cerit, 2020), particularly in establishing a supportive ecosystem that nurtures the development of students’ entrepreneurial skills. We found that school governance plays a pivotal role in building strong connections and maintaining proximity to other actors within the network, such as public educational service organizations. Past research has demonstrated that an important node in the network is local organizations, which can support teachers by providing resources and creating a favorable environment for entrepreneurship education in schools (Impedovo & Khatoon Malik, 2021); support entrepreneurship education programs in schools (Zollet & Monsen, 2023); and act as a bridge between theoretical and practical knowledge (Serpente et al., 2025). However, this study found that local organizations are less involved in the network and play a marginal role in connecting with network actors to foster entrepreneurship education. Thus, their contribution could be strengthened in the context in which we conducted our research.

Finally, the study examined the expected network envisioned by respondents and found that network management is expected to act as the central hub, connecting otherwise weakly linked actors such as families, funders, and local organizations. This reflects a top–down structure, where coordination and decision-making flow primarily through a centralized authority (Perry et al., 2012). By contrast, the existing network operates in a more bottom–up manner, with teachers holding the highest closeness centrality and driving daily interactions. This mismatch between expected and actual dynamics highlights a potential disconnect between formal coordination structures and operational realities. It also underscores the need to formally recognize and resource the bridging role of teachers, aligning governance and support systems with the actors who actually sustain cohesion and interaction within the network.

ImplicationsTheoretical implicationsThis study has several theoretical implications that confirm findings of existing literature (e.g., De Luca et al., 2020; Liguori et al., 2019) by supporting the importance of entrepreneurship education in fostering business intentions and preventing early school dropout and NEET development and expand on previous findings by extending the study context to earlier stages of education. That is, while previous research has generally explored entrepreneurship education primarily in higher education (e.g., Åmo & Åmo, 2013; Premand et al., 2016), this research highlights the importance of introducing entrepreneurship education at the primary and lower secondary school levels to build competencies early, such as creativity, problem-solving, and decision-making (McCallum et al., 2018). Thus, our study expands current theoretical understanding by positioning entrepreneurship education as an early intervention mechanism rather than merely a tool for business creation.

The study also contributes to the existing literature that analyzes entrepreneurship education through the theoretical lens of social capital theory. In particular, the study expands on experiences already examined in other research settings by highlighting the potential of school cooperatives to strengthen the skills of younger students (Han et al., 2020), promoting school inclusion and the creation of networks of generative relationships (Tataw, 2023; Kamle et al., 2025).

In addition, while previous literature has emphasized the role of universities, businesses, and incubators in supporting entrepreneurship education (e.g., Longva et al., 2020), our findings emphasize the crucial role of local ecosystems, including schools, public institutions, social enterprises, and families, in effectively promoting entrepreneurship education at a younger age. The findings align with the triple helix model (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, 2000) by demonstrating that community-based entrepreneurship education can create long-term engagement and skills building for young people at risk of early school dropout and its negative consequences.

Moreover, while traditional entrepreneurship education literature (e.g., Nchu et al., 2015; Feola et al., 2019) has primarily focused on the economic benefits of such education, for example, fostering start-up creation or enhancing employability, our study suggests that entrepreneurship education also produces critical social outcomes, such as increased social inclusion and personal empowerment among young people, who can develop new hard and soft skills, as well as improve their resilience by learning from their mistakes. The study reinforces the idea that entrepreneurship education should not be considered solely as a vocational training tool but as a holistic tool for social inclusion, thus aligning with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Sheehan et al., 2017).

Finally, our findings validate many theories on social networks (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1992) and offer new perspectives that demonstrate that well-structured networks can foster more inclusive and dynamic ecosystems (Stam, 2015) that can respond to educational and social challenges in the entrepreneurship field.

Practical implicationsThis study also has important practical implications. We found that teachers and school governance are key actors of the local network in fostering entrepreneurship education. This result suggests concentrating resources, training, and strategic responsibilities on these actors to optimize the flow of information and improve network efficiency. Thus, given that teachers connect actors who would not otherwise be directly linked and serve as bridges in communication and partnerships between different actors (e.g., school and families, school and local institutions, school and cooperatives), this study suggests creating educational programs for teachers to enable them to deliver entrepreneurship education and therefore entrepreneurial skills among students more effectively. To achieve this, we recommend recognizing and enhancing the role of teachers in the design of educational and social networks by formally involving them in working groups, agreements, and co-design processes.

Compared with previous practical experiences identified in the literature, local organizations are underutilized or poorly integrated within the local network investigated in our case study. This comparison suggests involving local organizations in entrepreneurship education through focused initiatives, such as events, partnerships, or workshops, to increase their inclusion in the network and leverage their potential to further develop entrepreneurship education. For example, local authorities could make entrepreneurship education more accessible and targeted.

The presence of more actors in the network (e.g., school governance, local organizations, and social enterprises) suggests the creation of collaborative ecosystems. For this reason, schools should invest more in programs that continue to promote interdisciplinary projects and partnerships across different actors to broaden the influence of educational initiatives in the entrepreneurship field. In creating this ecosystem, other financial partners should be considered to create more stable relationships. Implementing match-funding schemes between public and private finance is fundamental for engaging local communities and financially supporting multiple goals aimed at reducing school dropout rates.

The examination of the expected local network suggests that it would be beneficial to entrepreneurship education to broaden the number of actors belonging to the local network and identify actors that design and manage the network. For example, in the educational field, network management could be performed by a school or school governance coordinating entrepreneurial activities. For this purpose, its stability and operational capability must be a priority for the success of the network. In addition, we identify the benefit of assessing the strategic importance of existing connections to identify those that can be optimized or strengthened. Thus, local organizations, firms, and granters should be more involved through strategic partnerships, collaborative projects, or incentives because they can embed entrepreneurship educational activities in the local context and, thus, ensure that projects are relevant to the territory and have a lasting impact. Partnerships between public educational service organizations and firms could be developed to offer practical experience and mentoring. Further, families should be actively involved professionally or personally in educational programs, workshops, or seminars because they can support children in developing entrepreneurial skills that are useful to start a business and improve their problem-solving skills.

In brief, this study recommends strengthening the role of the network designer and manager and involving more peripheral actors to exploit resources and expertise that are not yet fully utilized.

The study, therefore, suggests undertaking further SNA to provide data to design strategic initiatives and policies to strengthen partnerships across actors. Furthermore, given the pivotal role played by schools in defining and continuing entrepreneurship educational programs, government policies could include incentives for the implementation of educational programs focused on entrepreneurship, school–business collaboration, and the creation of local hubs and support for social cooperatives. Finally, to limit the differences between territories that prevent good practices from being disseminated, education policies could aim to create more direct links between peripheral and central actors to reduce their marginality.

ConclusionsDrawing on the lens of social capital theory, this research investigated the role of entrepreneurship education in reducing school dropouts and preventing the development of NEET young people through promoting the development of key competencies for lifelong learning proposed by the European Union (European Commission, 2019). The findings revealed that establishing school cooperatives in early education enhances students’ social capital, enabling them to engage in a network of inclusive relationships. The research also identified factors that support entrepreneurship education, particularly in addressing early school dropout rates and the development of NEETs. In addition, it emphasizes the importance of establishing a strong and extensive relational network in which teachers and school governance play a key role in creating a supportive ecosystem, reflecting a more distributed, bottom–up structure. In contrast, the expected network anticipates a top–down network structure dominated by network management, suggesting a misalignment between formal governance and actual operational dynamics.