Firms face many obstacles in their pursuit of innovation. However, the mechanisms that enable firms to surmount these challenges and foster innovation are less understood. This study thus investigates whether the better performance of firms with higher human capital is due to their increased ability to overcome obstacles to innovation. Our estimation strategy accounts for the fact that facing obstacles is endogenous by correcting for the sample selection bias that is involved in determining which firms face obstacles. It appropriately estimates the impact of firms’ skill intensity on their propensity to innovate under two sets of circumstances—facing obstacles or not. Using a combination of rich survey and register data from over 2000 Danish firms for the period of 2006 to 2018, we also address several other biases that could affect our estimation of the impact of skill intensity on overcoming obstacles. Our results provide strong evidence that firms facing challenges in their innovation process are more likely to succeed when they have higher skill intensity. This applies to large and small firms as well as to firms in the service and manufacturing sectors, and it applies regardless of the type of innovation and, to some extent, which obstacles they face. Interestingly, we find that increasing skill intensity has no impact on the likelihood of innovation for firms that do not face obstacles. In contrast, firms that face obstacles can increase their likelihood of innovation by up to 25 %-points through higher skill intensity.

There is broad agreement that innovation is an important measure of firms’ performance (Griliches, 1958; Crepon et al., 1998; Ugur et al., 2016) and is linked to firms’ competitiveness (Porter, 2008). This consensus explains why this view is often supported by policymakers and industry associations. At the same time, innovation is also difficult due to all kinds of financial, cost, knowledge, and/or market obstacles (Savignac, 2008; Blanchard et al., 2013). However, some firms are much better at dealing with these obstacles than others. This paper aims to examine whether factors exist that can help firms overcome obstacles.

Previous studies have shown that higher skill intensity through training or formal education increases firms’ propensity to innovate (Dostie, 2018; Kromann & Sørensen, 2024). It is believed that more skilled workers are better able to generate and apply knowledge and techniques to create ideas for novel innovations, thereby making crucial contributions to their firms’ efficiency and competitive advantage (Hewitt-Dundas, 2006; Joshi & Jackson, 2003). A well-educated workforce also tends to be better equipped to turn ideas into practical solutions that can be brought to market. Finally, it is believed that educated workers are often more adaptable and flexible in their thinking, which enables them to better anticipate and respond to market changes (Leiponen, 2005; Baldwin & Lin, 2002; Gibbons & Johnston, 1974; Barth et al., 2018). This article examines whether better skills can help firms facing obstacles to overcome them, thus leading to better innovation outcomes.

Radas and Bozic (2012) were the first researchers to empirically address the issue of which factors enable firms to successfully overcome obstacles and innovate. They concluded that among the firms that encountered delays or abandonment of their innovation projects, the firms that collaborated or had former innovations were more likely to create innovative products. They simultaneously estimated a system of equations, accounting for the interdependence between the innovation equation and an equation for whether a project was delayed. However, they had no information on workers’ skills. Another difference was that unlike our research, they did not treat the facing of obstacles as a sample selection problem.

D'Este et al. (2014) were the first researchers to analyze whether workers’ skills have an impact on their likelihood of facing obstacles. They found that human capital has a negative impact on the likelihood of facing knowledge and market obstacles but that it has no impact on the likelihood of facing cost obstacles. They came to the conclusion that human capital has a significant impact on reducing obstacles to innovation by only examining obstacles and not examining whether firms overcome them and innovate. Our empirical model, presented in "Empirical Strategy", includes both innovation and facing obstacles as firm-level outcomes.

Other studies use a similar strategy as D'Este et al. (2014), exploring how different firm characteristics determine whether firms face obstacles. Pellegrino (2018) examined how firms’ age, impact if facing seven different obstacles in the areas of cost, knowledge, and market. Pellegrino found a negative association between a firm's age and its assessment of both internal and external shortages of financial resources. Baldwin and Lin (2002) focused on technology and concluded that information on obstacles in technological surveys should not be interpreted as impenetrable barriers that prevent technology adoption. Rather, these surveys describe areas in which successful firms face and solve problems. Tourigny and Le (2004) hypothesized that obstacles to innovation can vary depending on factors such as technological intensity, novelty, location, impact of government support programs, competitive environment, and firm size. They concluded that firms that face intense competition, operate in high-tech industries, and are medium- or large-sized are more likely to report themselves as facing obstacles to innovation. Their results also show that firms are seemingly able to overcome most obstacles to innovation. However, these studies do not examine the mechanisms at play.

Another recent stream of research considers the facing of obstacles to be a determinant of firms’ innovation activities. For example, Arza and Lopez (2021) studied how obstacles to innovation affect firms of different sizes. They concluded that small firms are more affected by obstacles, including cost obstacles in particular, compared to larger firms. While the innovation model created by Arza and Lopez (2021) considers the selection of R&D activities, it does not allow for the direct identification of factors that help firms overcome obstacles. Arza and Lopez (2021) also focused on innovation activities, while we use the richness of our data to study more relevant innovation outcomes. Finally, compared to Arza and Lopez (2021), we have more detailed measures of skill intensity. They used the proportion of workers in professional and technical roles as a proxy for skills as a control variable in their regressions, while we have information on all workers’ education levels.

To study the relationship between overcoming obstacles and workers’ skill intensity, as obtained from their formal education, we have employed longitudinal linked Danish register and survey data from the period of 2006 to 2018. This data is especially rich, as it contains detailed information on three types of innovation, ten possible obstacles to innovation, and more detailed education information at the worker level. We also have information on many firm characteristics that could affect its’ innovation performance, such as their age, industry, financial vulnerability, and import and export status. Our information on linked workers also includes their age and seniority.

Our empirical strategy takes full advantage of this detailed data to tackle the four main challenges faced by researchers who are trying to estimate the link between workers’ skills and how firms that face obstacles can innovate. First, it should be recognized that there is a large element of randomness in determining which firms face obstacles, as some firms may be lucky while others may simply be unlucky. However, firms that pursue certain types of innovation, such as riskier types, are certainly more likely to face obstacles. This means that facing obstacles is endogenous to firms’ decisions on the types of innovation they pursue and the level of resources they allocate to the innovation process, which are linked to these firms’ internal characteristics. Our empirical strategy explicitly tackles this problem by correcting for the sample selection bias that shows up when determining which firms face obstacles. We aim to appropriately estimate the impact of firms’ skill intensity on their propensity to innovate under these two sets of circumstances—facing obstacles or not. Our results show that the failure to account for sample selection will lead to biased estimates.

Second, the data's longitudinal structure enables us to predate the educational information and other firm characteristics to before our data on the firms’ innovations and obstacles. This allows us to alleviate simultaneity bias, through which firms’ innovation performance can affect which workers are hired. Third, the detailed data allows us to identify and focus our analysis on firms that are willing to innovate, thus alleviating an additional selection bias. Finally, the availability of information on innovation outcomes allows us to avoid using innovation activities as a proxy for this information, as many previous studies have done. Our data indicates that some firms do not report their innovation activities, possibly because innovation is built into their everyday activities.

The data shows that 72 % of Danish firms faced at least one obstacle to innovation, while 26 % faced more than three obstacles to innovation. Interestingly, the likelihood of innovation increases with skill intensity, but only for firms that face obstacles. For a firm that does not face obstacles, the average likelihood of innovation is 50 %. This does not vary based on the level of education of its workforce. For a firm that faces obstacles, the firm's propensity to innovate increases from 58 % to 83 % when its skill intensity increases from below 12 % to above 50 %.

Our results provide strong overall evidence that firms that face challenges in their innovation process are more likely to succeed when they have higher skill intensity. This applies to large and small firms, to firms in the service and manufacturing sectors, and to high- and low-tech firms, and it also applies regardless of their form of innovation and which obstacles they face. Our results thus highlight one additional channel through which a more educated workforce helps firms to innovate. Namely, better educated workers can directly influence innovation performance and can also lead to more innovation, as educated workers are better able to overcome obstacles to innovation. These results are important for companies that grapple with obstacles to innovation as well as for politicians who are striving to enhance innovation in society.

Data and summary statisticsWe are using data from Statistics Denmark. Our information on innovation activities and obstacles comes from the Community Innovation Survey (CIS). This is a mandatory innovation survey that is sent each year to a new group of firms that is selected by Statistics Denmark as a representative sample of all Danish firms. The CIS provides detailed information on firms’ products, services, and processes innovation activities (see details in Table 2 and Appendix 1). In 2018, the CIS also included information on whether firms encountered obstacles affecting their innovation levels. Their questionnaire distinguished between three different categories of obstacles—money, knowledge, and market (see details in Table 1 and Appendix 1). Our main focus is on firms’ innovation outcomes from the 2018 wave of the CIS, which reports on innovation and obstacles from the period of 2016 to 2018. However, we also use information on firms’ innovation activities for the period of 2006 to 2015, using CIS data for earlier periods in our empirical strategy.1

Obstacle questions in CIS divided by obstacle types.

Notes: Each question is answered on a scale taking four values: 1 Great importance. 2 Some importance, 3 Little importance, 4 Not relevant. Data on Danish manufacturing and service firms in the period 2016–2018. The table shows the percentage of firms in each cell.

In line with previous work (e.g., D'Este et al., 2014; Arza & Lopez, 2021; Holzl & Janger, 2012), we first excluded firms with no declared intention to innovate from our sample. This was done to correct for the sample selection bias that would arise from asking firms that were not willing to innovate about their obstacles to innovation.2 This was implemented by using two questions from the survey. The first question asks whether the firm has encountered any obstacles to innovation, including money, knowledge, and market-related obstacles (see Appendix for details). The second asks whether the firm has been involved in any innovation activities, including product, service, and process innovations, within the last ten survey years (see Appendix for the questionnaire).

Using these two types of questions, we classified a firm as not being interested in innovation if the following two criteria were met:

- •

No innovation activities or obstacles were reported in the period of 2016 to 2018.

- •

No innovation activities were reported in the period of 2006 to 2018.

Applying these criteria, we excluded 12 % of our original sample and were left with a sample of 2604 firms. Previous studies excluded 31 % (D'Este et al., 2014) and 25 % (Savignac, 2008) of their samples, respectively, due to some of their sample firms not undertaking any innovation activities. If we only use the first of these criteria, in line with earlier studies, we can exclude a similar percentage of 27 %. However, we believe that too many firms were excluded from these studies, as information on their earlier innovation activities was not available. Finally, firms were excluded if they lacked educational information or other information that was used in the empirical analysis, leaving us with a sample of 2223 firms.

The firms’ innovation outcomes were measured by a dichotomous variable that indicated whether the firm engaged in innovation. This variable was conditional on whether the firm faced obstacles in the innovation process. We further explored the links between innovation and obstacles by disaggregating the results according to innovation type (product, process, and service) and obstacle type (money, knowledge, and market). However, most of our results group these obstacles together, as they tend to be complementary (Galia & Legros, 2004).

Table 1 presents the share of firms who stated in their responses that each obstacle was of great importance (1), some importance (2), little importance (3), and not relevant (4). The obstacles are divided into three types, a division that closely follows the one suggested by the Oslo Manual. For each question, we first created dichotomous variables, taking the value of 1 if the firm reported at least one of the obstacles to have great importance or some importance (values 1 or 2) and otherwise taking the value of 0. Next, we created a dichotomous variable for each of the three types of obstacles—money, knowledge, and market. They took the value of 1 if the company reported at least one of the obstacles to have great importance or some importance and otherwise took the value of 0. Finally, we created an overall indicator, taking the value of 1 if the company reported at least one of the 9 obstacles and otherwise taking the value of 0. Table 1 shows that most firms reported that they struggle with “costs too high,” “too much competition in the company's market,” and “lack of access to external knowledge.” However, “lack of credit/equity” and “public subsidies” are among the least reported struggles of some importance or great importance. All three types of obstacles are generally of concern to these firms.

Table 2 presents the share of firms that innovated in an overall sense or within three different categories—product, service, and process. The innovation variables are constructed from nine survey questions into dichotomous variables that take the value of 1 if the firms have innovated within each respective innovation type, otherwise taking the value of 0. The exact wording of the questions is listed in Appendix 1. The summary statistics are shown for the entire sample in column 1, for firms that are innovators in column 2, and for firms that have no innovation activities in column 3. Innovation activities are defined as reporting positive R&D and/or innovation expenses (56 % of respondents). Finally, column 4 shows summary statistics for firms with no innovation activities (44 % of respondents).

Summary statistics for innovation.

Notes: The table presents the share of firms that are innovative. Column 2: if a firm succeeded with being innovative in the period 2016–2018. Column 4: If a firm used money on R&D or innovation in the period 2016–2018. The sample only includes firms that are interested in being innovative.

Column 1 of Table 2 shows that 64 % of the respondent firms are innovative, with process innovation being the most prevalent form (55 %). Surprisingly, 45 % of firms that don't have innovation activities are innovative, and of these, 89 % achieve process innovation. This could indicate an issue where some firms are not reporting their innovation activities. This may occur because innovation is integrated into these firms’ processes and is thus difficult to separate from their other operational activities. This is one of the main reasons why we use innovation outcomes rather than innovation activities as our outcome variable in our empirical analysis.

Fig. 1 reports the relationship between innovation outcomes and facing obstacles (see also Table A3). Interestingly, the likelihood of innovation, regardless of its type, increases with the number of obstacles that the firm faces. This illustrates the importance of accounting for selection biases in facing obstacles to innovation.

Fig. 1 also shows that firms have the hardest time overcoming obstacles and innovating when they only face market obstacles. For service innovation, firms appear to be most successful at overcoming obstacles and innovating when they face money and knowledge obstacles and least successful when they face market obstacles. The pattern is similar for product innovation, while for process innovation, firms seem to more easily overcome obstacles and innovate when they face all three types of obstacles.

Registry dataWe have enriched the previously described survey data by using firm and worker identifiers to merge it with registry data. This gives us additional information on firms and workers that could be linked to their innovation performance. More specifically, we use registry data information on the firms’ number of employees, export shares, age, market power, industry, geographic area, financial vulnerability, and workforce education. To avoid simultaneity bias, these additional variables are from 2015, the year preceding the years covered by the data on innovation outcomes from the CIS 2018.

The next few tables analyze the correlations between innovation, obstacles, and skill intensity. In Table 3, the firms are categorized into four groups based on their skill intensity (the share of workers with at least 14 years of education). For example, around 25 % of these firms have a skill intensity of 12 % or less. Each row of Table 3 then shows the likelihood of innovation, depending on whether these firms face any obstacles, and if so, which types of obstacles they face.

Likelihood of being innovative depending on faced obstacles and skill intensity.

Notes: The table shows the share of firms innovating in each cell.

For example, the first row shows that the likelihood of innovation increases with skill intensity for the group of firms that do not face obstacles. There is a 46 % likelihood of innovation in the low-skilled group, increasing to 53 % in the higher-skilled group. This positive relationship grows steeper when we look at firms that face obstacles, and it is especially pronounced when examining firms that face two or three types of obstacles. For example, firms facing all three types of obstacles have a 58 % likelihood of being innovative for firms with the lowest skill intensity compared to 83 % for firms with the highest skill intensity. This potentially indicates that there is a positive relationship between overcoming obstacles and having higher skill intensity. It remains to be seen whether this relationship persists in a more robust statistical modeling of the relationship between skill intensity, facing obstacles, and innovation outcomes.

Given that different types of innovation involve very different innovation processes, a well-educated workforce may find it easier to overcome obstacles to certain types of innovation compared to others. Fig. 2 shows the relationship between the skill intensity levels for three different types of innovation. For product and process innovation, Fig. 2 implies that the greatest impacts occur at low to medium skill intensity levels. However, for product innovation, the influence of skill intensity appears to diminish at higher skill intensity levels, while for process innovation, the effects remain the same at medium and higher skill intensity levels. For service innovation, the impact is greatest when moving from medium to high skill intensity. An initial visual impression thus shows that more skill-intensive firms are better at overcoming obstacles to innovation, regardless of the type of innovation involved (see also Table A4).

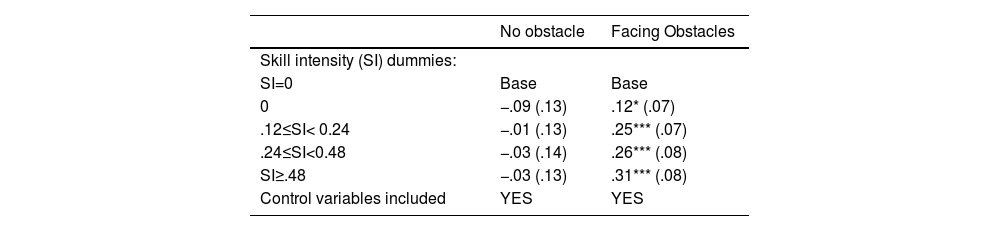

Another interesting question is whether there is a particular area or length of tertiary education that is better able to overcome obstacles to innovation. Table 4 shows that the propensity to innovate among firms that do not face obstacles is around 50 %, a number that is very similar across all types of education. However, in firms that face obstacles, the propensity to innovate increases significantly with higher skill intensity, from around 60 % for firms with a skill intensity level close to zero to 80 % for firms with a skill intensity level above 12 %. It is worth noting that the greatest impact appears to occur at lower skill intensity levels. A similar pattern can be seen in Table 5 across different lengths of educational experience. All this evidence thus suggests that skill-intensive firms are better able to overcome obstacles to innovation, regardless of each employee's speciality or length of tertiary education.

Likelihood of being innovative for education types depending on faced obstacles and skill intensity.

Notes: The table shows the share of firms innovating in each cell. Within each education type, firms have been divided into four equal sized groups.

Likelihood of being innovative for education length depending on faced obstacles and skill intensity.

Notes: The table shows the share of firms innovating in each cell. Within each education length, firms have been divided into four equal sized groups.

Our study investigates whether skills help firms overcome obstacles to innovation, using a novel approach that accounts for the fact that facing obstacles is not random. Firms encounter obstacles due to specific characteristics and behaviors, which makes it essential to treat this as an endogenous process. To address this, we estimate a system of three interconnected equations. This allows us to simultaneously analyze the innovation outcomes for firms that face obstacles, the innovation outcomes for firms that do not, and the probability of facing obstacles in the first place.

The dependent variable in our first two equations is the innovation outcomes (innoit), a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if firm i at time t had product, service, and/or process innovation. For firms facing obstacles, the likelihood of innovation is modeled as:

For firms not facing obstacles, the likelihood of innovation is given by:

These two equations allow us to distinguish how innovation drivers differ between firms that encounter obstacles and those that do not.

These equations incorporate firm-specific factors such as skill intensity (skillit−3), which is measured as the share of workers with at least 14 years of education, a dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the firm uses external resources to carry out R&D (rd_externalit). As well as R&D costs per employee (inno_costit); collaboration on innovation with customers and suppliers (collabCit,collabSit); firm size dummies (sizeit−3); export share of sales (exportit−3); diversity in the employees’ ages and tenures, measured as standard deviations of their respective means (age_sdit−3,tenure_sdit−3); the resources available within each firm, measured as return on assets (roait−3); and industry dummies (Iit−3′). Finally, there is the Herfindahl–Hirschman index of market concentration (hhiit−3), which is calculated as the square of the marked share of sales in Denmark within the industry that they operate in.3 For this equation, εit is the residual error term.

By using lagged explanatory variables (e.g., skill intensity, firm size, export activity, and market concentration), we reduce simultaneity bias, ensuring that our estimates are more likely to reflect causal relationships.

The originality of our approach lies in the third equation, which models the probability of facing obstacles as an endogenous process:

The independent variables that determine each firm's probability of facing obstacles are assumed to be the log of sales (ln_sales); the Lerner index, which is included as 9 dummies (competitionit−3) to allow for a non-linear relation to capture each firm's market power; and collaboration on innovation with universities and consultancies (collabUit,collabKit). Competition is included in both the obstacle and innovation equations, while in the innovation equation, it is included as the Herfindahl–Hirschman index.4 The following variables that also appear in the innovation equation are included as determinants of facing obstacles: rd_costitrd_externalit, and skillit−3,agesdit−3,tenuresdit−3,sizeit−3.5

Our estimation strategy relies on accounting for the self-selection bias in Eqs. (1) and (2) due to the non-randomness involved in facing obstacles. This is achieved by estimating both equations simultaneously with Eq. (3) and, more importantly, allowing the covariance between εit1 and uitand the covariance between εit0 and uit to be non-zero:

In effect, we are thus estimating an endogenous switching regression model (Lokshin & Sajaia, 2004), in which we expect σ1u<0 and σ0u<0. This means that a higher probability of facing obstacles is associated with lower innovation and a lower probability of facing obstacles is associated with higher innovation.6 Estimation can be achieved by using full-information maximum likelihood methods or by taking advantage of the two-stage specification method outlined by Heckman (1979). This method involves first estimating Eq. (3) as a probit model based on the probability of facing obstacles and then constructing the corresponding inverse Mills ratio, which is to be added as an explanatory variable in the appropriate versions of Eqs. (1) and (2).

Our primary interest lies in the role of skills, with a particular focus on the coefficients α01 and α00 for skill intensity. If the impact of skills is greater for firms that face obstacles (i.e., α01>α00), this suggests that skilled workers are especially effective in helping firms overcome barriers to innovation. By integrating these relationships into a unified framework, our methodology provides a deeper understanding of how firms navigate challenges. It also highlights the importance of targeted policies that support innovation in more constrained environments.

Empirical findingsThe results section first examines the role of tertiary education in overcoming obstacles to innovation, including robustness checks in "The Role of Tertiary Education in Overcoming Obstacles". "Tertiary Education and Different Types of Obstacles" digs deeper and examines the role of tertiary education in overcoming specific types of obstacles, whereas "Tertiary Education and Types of Innovations" focuses on different types of innovations. "Tertiary Education Field and Length, Obstacles, and Innovation Outcomes" returns to overall innovation outcomes and obstacles and examines whether the type and length of tertiary education is important. Finally, "Tertiary Education Diversity, Obstacles, and Innovation Outcomes" explores whether educational diversity is important for overcoming obstacles and innovating.

The role of tertiary education in overcoming obstaclesIn this subsection, we use the empirical strategy presented in "Empirical Strategy" to analyze whether firms that overcome obstacles are more likely to be skill intensive. Tertiary degrees are considered to be an important source of firm-level heterogeneity, explaining differences in innovation success, profitability, and many other market-related variables (Watson et al., 1993; Berliant & Fujita, 2008; Drach-Zahavy & Somech, 2001; Hong & Page, 2001; Lazear, 1999; Osborne, 2000). However, little is known about their effects on overcoming obstacles to innovation. Educated workers tend to be better able to generate and implement new ideas and recognize new opportunities or approaches, and they are also more likely to build professional networks (Hewitt-Dundas, 2006; Joshi & Jackson, 2003; Barth et al., 2018; Cohen & Levinthal, 2000; Leiponen, 2005).

Table 6 presents coefficient estimates from the endogenous switching regression model (Eqs. (1) to (3)), allowing the coefficients to differ between the firms that face obstacles (column 2) and the firms that do not (column 1). The coefficient of interest shows that skill intensity has a positive impact on the probability of innovation for both types of firms. However, the coefficient is only statistically different from zero for firms that face obstacles. This suggests that only firms that face obstacles to innovation receive positive returns from a higher proportion of educated workers. Firms that overcome obstacles to innovation are thus more likely to be skill intensive.

Endogenous switching regression model: coefficient estimates from the innovation equation.

Notes: The model is estimated using an endogenous switching regression, where the selection equation is facing obstacles or not. The coefficients from the first regression are shown in the Appendix Table A5. The model is estimated using the two-step consistent estimator. The findings are the same if using the full maximum likelihood estimator.

The estimated results show that the residuals in the obstacles and in the innovation outcome equations are correlated, thus demonstrating the need to correct for selection biases. The estimated correlations between the residuals are σ1u=−0.22 and σ0u=-0.38, respectively, for firms with and without obstacles. This fits our prior finding that a higher probability of facing obstacles is linked to lower innovation performance. If we estimate a linear probability model for the selection equation, the results show that 30 % of the variation in facing obstacles is explained by this model.

To confirm whether the pattern in Table 3 still holds after controlling for other firm characteristics, we reran the regression in Table 6 including four skill intensity dummies, using firms with no educated workers as the base. These figures are listed in the appendix in Table A6. As in Table 3, the firms are divided into groups of similar size, depending on the share of the workforce being educated. We did this to find out whether all the firms increased their likelihood of innovation by increasing their educational share. This result confirms that all the firms facing obstacles benefit from having more educated workers to successfully innovate. The higher their share of educated workers, the more likely the firm is to be innovative when facing obstacles.

As anticipated from Table 3, the regression results in Table A6 further confirm that, regardless of the share of the workforce being educated, having more educated workers does not boost the chances of innovation for firms that do not face obstacles.

The results from Table 6 allow us to conclude that firms facing obstacles increase their likelihood of innovation when they hire more educated workers. However, firms that do not face obstacles do not increase their likelihood of innovation when they hire more educated workers.

Robustness checksTo check the robustness of the previous results, we have re-estimated our model from Table 6 for different sub-samples. We also loosened up the definition of “facing obstacles” by including firms that answered that an obstacle was of great importance, some importance, or low importance. Tables 7, 8, and A7 report the corresponding results.7

Robustness check of Table 6.

| Innovation | Manu-facturing | Service | Low tech | Publishing | Medium & high tech |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill intensity: | |||||

| No obstacles | .14 (0.16) | .09 (0.20) | −0.10 (0.20) | .42 (0.39) | .24 (0.19) |

| Facing obstacles | .27***(0.09) | .26**(0.13) | .28** (0.14) | .74** (0.31) | .22** (0.14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables incl. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| # of firms | 973 | 1250 | 974 | 107 | 1142 |

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. * indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level. The firms are divided into low and medium to high technology firms using Eurostat indicators on high-tech industry and knowledge-intensive services. The Publishing industry that includes movie, tv and music production and radio- and tv-stations is considered a high knowledge-intensive service in the definition used, but it is an industry that is creative, which is normally not considered as high technology, why we have included the industry on its own as an in-between industry.

Robustness check of Table 6.

| Innovation | Sale≤45mio | Sale>45mio | # emp≤30 | # emp>30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skill intensity: | ||||

| No obstacles | .01(0.27) | .20(0.14) | −0.01 (0.21) | .25 (0.16) |

| Facing obstacles | .46***(0.13) | .19**(0.09) | .35***(0.12) | .23**(0.10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables included | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| # of firms | 537 | 1686 | 616 | 1607 |

| Share of the population | 50 % | 50 % | 50 % | 50 % |

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

In columns 1 and 2 of Table 7, we estimate the model separately for firms in the manufacturing and service sectors, since these sectors are often assumed to have different innovation processes. The results show that firms in both sectors that face innovation obstacles are more likely to overcome them and innovate with higher skill intensities. Likewise, in columns 3 to 5 of Table 7, we estimate the model separately for firms based on their industry's technological level. Once more, the findings are similar to those in Table 6.

In columns 1 and 2 of Table 8, we split firms by their sales volume, using a threshold of 45 million DKK. The results for the two groups of firms are similar. In columns 3 and 4 of Table 8, the sample is split into smaller and larger firms, using a threshold of 30 employees. Again, skill intensity coefficients are positively statistically different from zero only in the case of firms that face obstacles, thus confirming that neither group is driving these results. For both sales and employment, the smaller firms on average have a higher return on their skill intensity. We believe that this is due to two factors. First, smaller firms generally have fewer educated workers. Second, smaller firms may be more likely to report something as an obstacle than larger firms, and these obstacles may therefore be easier to overcome. The benefit to hiring an additional educated worker is thus higher for smaller firms.8

Finally, in Appendix Table A7, we show that our results are also robust to the specific sample being used and the construction of the obstacle variable. Consistent with the existing literature, firms that were unwilling to innovate were removed from Table 6. In the first column of Table A7, we show that regardless of whether these firms are included, it does not matter to our results. In column 2, we deleted firms that reported no innovation from 2008 to 2018, ignoring whether the firms’ faced obstacles. In columns 3 and 4, we changed the way in which the dichotomous obstacle variable was constructed, depending on whether the firms reported their obstacles as having great, some, or low importance. See the notes for Table A7 for details. All the cases lead to the same findings on the impact of skill intensity on overcoming obstacles to innovation.

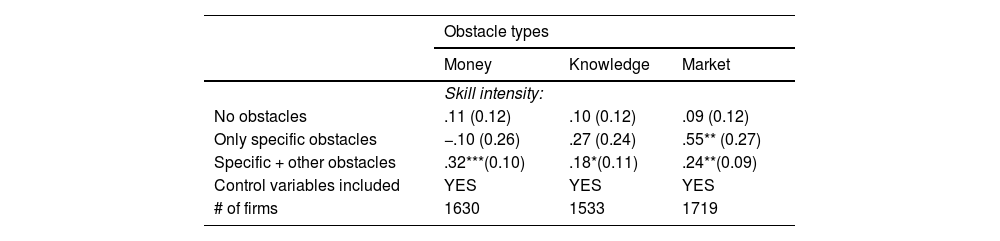

Tertiary education and different types of obstaclesIn recent articles (e.g., Arza & Lopez, 2021; Jaureguy et al., 2023), the obstacles faced by firms are often broken down into three categories—first, cost and financial obstacles, second knowledge obstacles and third, market obstacles. Another interesting research question is thus whether firms with higher skill intensities are better able to overcome certain types of obstacles.

When examining cost and financial obstacles, several studies have shown that these costs can deter innovation (c; Savignac, 2008; Alvarez & Crespi, 2015; Bond et al., 2005; Mohnen et al., 2008). One could argue that until the innovation process starts, it may be difficult to identify knowledge and market obstacles. However, when a firm's innovation process is underway, it may reveal knowledge gaps that were previously concealed (Chesbrough, 2010). The existing literature on both cost and financial obstacles as well as knowledge and market obstacles has been silent on the role of higher skill intensity in overcoming these obstacles.

We have modified our endogenous switching model to allow the probability of innovation to depend on whether each firm faces a specific type of obstacle, and if so, whether it is facing it alone or together with other obstacles. The dependent variable in Eq. (2) began as a binary variable that takes the value 1 when a firm faces obstacles to innovation and 0 when it does not. It has now changed to an ordered variable that takes the following values:

- •

0: Firms not facing any obstacles to innovation.

- •

1: Firms facing obstacles only within a specific obstacle type. For example, a firm in this group could only face market obstacles.

- •

2: Firms facing obstacles both within one specific obstacle type and at least one of the other obstacle types. For example, a firm in this group both face the specific obstacle type e.g. market obstacles and also faces knowledge and/or money obstacles.

- •

(missing): Firms only facing obstacles outside a specific obstacle type. For example, a firm in this group do not face the specific obstacle e.g. market obstacles, but face obstacles other than market obstacles. These firms are left out of the analysis.

Summary statistics on these newly constructed variables can be found in Appendix Table A8. The proportion of firms facing only one obstacle type is around 7 % across all three obstacle types. Whereas the proportion of firms facing at least two obstacles is around 38 %.

Table 9 shows the results for the skill intensity variable from the innovation outcome regressions, where the coefficients of the independent variables are allowed to vary between the different groups. Column 1 focuses on money obstacles, column 2 focuses on knowledge obstacles, and column 3 focuses on market obstacles. The dependent variable is the same in all three columns—the innovation outcome as in Eq. (1).

Estimation coefficients for skill intensity for different obstacle types.

Notes: The estimation method and control variables are the same as in Table 6. Firms that only face obstacles other than the one in focus in the column were removed from the sample. For example, for column 1, we deleted firms that only face obstacles other than money/financial obstacles. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

Focusing on money obstacles, the results show that only firms that report a minimum of two types of obstacles gain from having educated workers. This result is similar to that of D'Este et al. (2014), who found that having educated workers does not help firms overcome money obstacles.

The result is similar for knowledge obstacles. For market obstacles, having an educated workforce increases the likelihood that firms will overcome these obstacles and innovate. Fig. 1 shows that firms that only face market obstacles have the lowest likelihood of innovation out of all firms that face obstacles. This indicates that market obstacles are harder to overcome. However, firms with educated workers are more likely to overcome these obstacles and innovate. This finding is also similar to the conclusion that D'Este et al. (2014) made by using obstacles as the dependent variable.

We can thus conclude that a higher share of workers with a tertiary education increases the likelihood of overcoming obstacles only when struggling with market obstacles alone or in combination with other obstacles. Higher skill intensity does not help firms that only face knowledge obstacles.

Tertiary education and types of innovationsNijssen et al. (2006) point out that there are differences in the development processes for various types of innovation. That implies that a well-educated workforce may find it easier to overcome obstacles for certain types of innovation than for others. We thus divide innovation into three types: product, service, and process. According to the review by Toner (2011), workforce skills are a prerequisite for continuous product and service improvements. Educated workers can also provide leadership and project management expertise to ensure that process innovation initiatives are implemented effectively and stay on budget. Carvache-Franco et al. (2022) state that the main obstacle to process innovation is a lack of funds. However, there is no information on whether skill intensity plays a role in a firm's likelihood of overcoming these obstacles. In this section, we thus examine whether firms that overcome obstacles to innovation are more likely to be skill intensive.

Table 10 shows the results for the three innovation types listed in columns 1, 2, and 3. The dependent variable for product innovation takes the value 1 if the firm has introduced product innovation and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any innovation activities. For service and process innovation, the dependent variables are constructed in a similar way.

Estimation coefficients for skill intensity for different innovation types.

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. The dependent variable for product innovation takes the value 1 if the firm has introduced product innovations and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any innovation activities. For service and process innovations, the dependent variables are constructed in a similar way. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

The results are very similar across the different types of innovation. Firms that do not face obstacles to innovation thus do not increase their likelihood of innovation through higher skill intensity, while firms that face obstacles increase it. This applies to all three innovation types and is consistent with Fig. 1. Regardless of the type of innovation, firms with higher skill intensity are more likely to overcome obstacles and innovate.

To better understand the relationship between obstacles, skill intensity, and innovation type, Table 11 divides the innovative firms according to their innovation strategies.9 In column 1, the dependent variable takes the value 1 if a firm has introduced only one type of innovation and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any other innovation activities. Similarly, in column 2, the dependent variable takes the value 1 if a firm has introduced product and service innovations and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any other innovation activities. Interestingly, the table shows that higher skill intensity can help overcome obstacles if the firm either introduces one or all three types of innovation or if it has an innovation strategy that includes product and process innovation. The only innovation strategies that did not benefit from higher skill intensity are thus the ones having two types of innovation, including service innovations.

Estimation coefficients for skill intensity for different innovation strategies.

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. In column 1, the dependent variable takes the value 1 if a firm has introduced only one type of innovation and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any innovation activities. Similarly, for column 2, the dependent variable takes the value 1 if a firm has introduced product and service innovations and 0 if the firm has not undertaken any innovation activities. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

We saw earlier that firms with higher skill intensity are more likely to overcome obstacles to innovation, regardless of the innovation type. In this section, we examine whether field and length of tertiary education matter.

Innovation often requires a multidisciplinary approach that involves the integration of diverse sets of knowledge and skills from different fields, such as engineering, social sciences, natural sciences, and design. The interaction of workers with different knowledge bases increases their ability to engage in problem solving and complex non-routine tasks (Chandrasekaran & Linderman, 2015). It is also believed that a diverse team of workers can positively influence the types of solutions being produced due to the workers’ different perspectives and opinions. This stimulates discussions and creates more creative solutions (Jackson & Joshi, 2004; Sollner, 2010; Faems & Subramanian, 2013).

In order to examine if field of tertiary education matters three groups were formed:

- •

Technical education, including engineering education.

- •

Social sciences, including business education.

- •

Other education, including arts, media and communications, educational, and health education.

The distribution of the skill intensity in each of the three fields of education is similar across the various firms (see Appendix Table A10). However, the near-zero correlation coefficient across these categories indicates that firms do not generally hire workers across different educational fields. Instead, they tend to favor one type of educational background over others. This specialization is evident in industries like manufacturing, where technical workers are preferred, and in travel agencies, where business backgrounds are preferred. Note that controlling for industry in our regressions already accounts for unobserved industry-specific differences that could be related to both skill intensity and innovation.

Table 12 shows the coefficients for six different skill intensity variables, still allowing the effects of skill intensity to vary between firms that face obstacles and firms that do not across three different educational fields. In column 1, the dependent variable is whether the firm is innovative, followed by specific types of innovations in columns 2 to 4. On the one hand, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that firms not facing obstacles do not increase their propensity to innovate by employing workers with tertiary degrees in engineering, social sciences and business, or other fields at a 1 % significant level. On the other hand, we find that firms facing obstacles can overcome them and innovate more easily if they have a workforce with a tertiary degree in engineering, social sciences (including business), and/or other fields (column 1). Since the estimated coefficients are significant across the different educational fields, we conclude that the field of study matters less as long as the firms have educated workers. However, it should be noted that the estimated effect is twice as large for social sciences, including business education, compared to the two other educational fields.

Estimation coefficients for skill intensity across education field for different innovation types1.

| Innovation type: | All | Product | Service | Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical educational background | ||||

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | .12 (.17) | .17(.16) | .03 (.16) | .01 (.18) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .49*** (.16) | .74*** (.19) | .63*** (.20) | .53*** (.17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Other educational background | ||||

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | .19 (.17) | .10 (.18) | −.12 (.17) | .12 (.19) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .23**(.11) | .19(.14) | .21 (.14) | .24**(.12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables included | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of firms | 2223 | 1528 | 1272 | 2040 |

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

1The conclusions from Table 12 holds when estimating the model separately for the service and manufacturing sectors.

If we look at the different types of innovation separately, we obtained similar results for process innovation. However, for product and service innovation, only having more workers with a tertiary degree in social sciences, including business education, results in firms being able to overcome obstacles and innovate more easily. We expected workers with a technical education to be able to help overcome obstacles that arise when struggling with process innovation, which has proven to be the case. However, we also expected workers with degrees in social sciences or business to be able to help overcome financial barriers to all types of innovation as well as market barriers to product and service innovation. Again, the result was as expected, with a positive significant coefficient for all three types of innovation but with the most pronounced effects on product and service innovation. Finally, we expected workers with an education in arts, media, communications, education, or health education (defined here as other education) to primarily be skilled at overcoming obstacles in the creative process when developing new products or services. However, only the coefficient in the regression for process innovation is significant here, although both the coefficient values and the standard deviations are similar in all three regressions. The general conclusion is thus that all types of education are good for innovation and that having an education within the social sciences, including business, has the greatest effect.

Finally, we looked at the length of the tertiary education. We split higher education into three categories based on length:

- •

Short-cycle tertiary education, 1–2 years post-secondary, college types.

- •

Medium-cycle tertiary education, 3–4 years post-secondary, bachelor's types.

- •

Long-cycle tertiary education, 4 or more years post-secondary, master's and PhD types.

Table 13 is structured analogously to Table 12, and it shows the coefficients for the skill intensity coefficient for different educational lengths. For short-, medium-, and long-cycle tertiary education, the coefficients are not statistically significant for firms that do not face obstacles, while they are positively statistically significant for firms that face at least one obstacle. The magnitude of the coefficients is highest for short-cycle tertiary education and lowest for long-cycle tertiary education.

Estimation coefficients for skill intensity across education length for different innovation types.

| Innovation type: | All | Product | Service | Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-cycle tertiary education | ||||

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | −.30 (.31) | −.23 (.31) | −.23 (.30) | −.54* (.33) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .37** (.18) | .60***(.22) | .46* (.24) | .43** (.20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-cycle tertiary education | ||||

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | .17 (.20) | .21 (.21) | −.13 (.19) | .04 (.21) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .29** (.13) | .31** (.15) | .36** (.16) | .33** (.13) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-cycle tertiary education | ||||

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | .13 (.16) | .06 (.17) | .13 (.14) | .09 (.17) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .22** (.10) | .22* (.13) | .22* (.13) | .23** (.11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables included | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of firms | 2223 | 1528 | 1272 | 2040 |

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

If we examine the different types of innovation separately, the coefficients for firms that do not face any obstacles with all three education lengths are still not statistically different from zero. For firms that face obstacles, the skill intensity coefficient is statistically significant at the 10 % level. Across the three innovation types, the skill intensity coefficient is around 0.22 for long-cycle degrees, 0.33 for medium-cycle degrees, and 0.50 for short-cycle degrees.

These skill-intensive firms are better able to overcome obstacles to innovation, regardless of the field or the length of the workers’ tertiary degrees, as all types of education help to overcome obstacles. An increase in the share of the workers with a tertiary education is ultimately what matters. However, it is also interesting to note that the coefficients decline with higher degrees of tertiary education. This may occur because too much specialization makes it difficult to collaborate to overcome obstacles.

The greatest difference across various education lengths is seen for product innovation. Product innovation is no longer limited to R&D teams but is an integrated effort across the entire supply chain, including workers, customers, and material and packaging suppliers. Obstacles to innovation can thus arise both in production and in R&D laboratories. This could explain our findings, as a 2023 quantitative study (Uddannelses- og Forskningsstyrelsen, 2023) found that workers with long-cycle tertiary education are better able to solve complex tasks and long-term challenges, while workers with short- or medium-cycle tertiary education are more capable of solving everyday tasks and operations.

Up until now, we have examined how varying lengths and types of education influence the likelihood of different types of innovation. However, it is possible that certain obstacles are more easily overcome with specific types or lengths of education. This is a topic that we explore further in Appendix Tables A12 and A13. We conclude from these tables that it is mainly workers with degrees in social sciences or business and those with short- or long-cycle tertiary education who help to overcome obstacles to innovation.

Tertiary education diversity, obstacles, and innovation outcomesFinally, in this subsection, we explore whether educational diversity within firms, specifically including horizontal diversity (education types) and vertical diversity (education lengths), plays a crucial role in overcoming obstacles and creating innovation. To estimate the impact of educational diversity on innovation, we first need to build diversity indices (see Kromann & Sørensen, 2024). This is commonly measured using the Hirschman–Herfindal index (Hirschman, 1964):

In this equation, pist is the proportion of workers in firm i for category s at time t, while S indicates the number of educational categories (vertical or horizontal, respectively). Low index values indicate less diversity, while high values indicate greater diversity.

With respect to educational background (horizontal educational diversity), we use similar categories as before: engineering/technical, business/economics (social sciences), natural sciences, and humanities. We do the same with education length (vertical educational diversity), distinguishing between unskilled, skilled, and short- (14 years), medium- (15–17 years) and long-term (18 years or more) education.

The horizontal educational diversity index shows whether firms tend to have employees with similar educational backgrounds (low index value) or with different educational backgrounds (high index value). This allows for an examination of whether mainly having employees with diverse educational backgrounds or with similar knowledge bases helps more in overcoming obstacles to innovation. The vertical educational diversity index is used to determine whether it is more advantageous to predominantly employ workers with the same educational level or with different educational levels to overcome obstacles to innovation.

Table 14 shows the results. For horizontal educational diversity, the coefficient values are positively statistically different from zero for overcoming obstacles and for innovation in general. However, when we disaggregate by type of innovation, we find that this is the case only for product innovation. When examining vertical educational diversity, the coefficient values are positive and statistically different from zero in overcoming obstacles and innovating for product, service, and process innovation. To overcome obstacles and ensure innovation, it is thus important that a company has employees with varying lengths of education. This finding is interesting, as we previously concluded that the length of education is less important. However, this result shows that mixing together workers with different lengths of education has a significant positive effect on overcoming obstacles and promoting innovation.

Estimation coefficients for horizontal and vertical skill diversity for different innovation types.

| Innovation type: | All | Product | Service | Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horizontal skill diversity | ||||

| No obstacles: skill diversity | .10 (.15) | .13 (.15) | −.03 (.14) | .18 (.16) |

| Facing obstacles: skill diversity | .17* (.09) | .26**(.11) | .18 (.12) | .13 (.09) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertical skill diversity | ||||

| No obstacles: skill diversity | −0.12 (0.19) | −0.00 (0.20) | −0.19 (0.20) | −0.14 (0.20) |

| Facing obstacles: skill diversity | .38*** (.12) | .58***(.14) | .44*** (.16) | .40*** (.12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables included | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| # of firms | 2223 | 1528 | 1272 | 2040 |

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

This study contributes to our understanding of how firms can overcome obstacles to innovation by focusing on the role of a skilled workforce. Our findings confirm that firms with higher skill intensity are better equipped to address the obstacles they face in the innovation process. This effect is consistent across different types of innovation (product, service, and process) and, to a certain extent, across different types of obstacles (financial, knowledge, and market). A better-educated workforce proves to be particularly effective in overcoming market-related obstacles. This aligns with the existing literature on the importance of skills in managing market complexity (e.g., D'Este et al., 2014). Studies examining the relationship between educational attainment and firms’ capacity to overcome obstacles to innovation are still rare. We have thus drawn inspiration from other studies that highlight the benefits of having an educated workforce.

First, due to their increased technical knowledge, enhanced critical thinking skills, improved capacity for creative thought, improved group collaboration, enhanced communication abilities, and enhanced problem-solving abilities, educated workers are more capable of tackling complex challenges to innovation (Mumford & Gustafson, 1988; Mumford et al., 2017; Anderson et al., 2014; Wang & Rode, 2010; Edmondson, 1999; Edmondson & Harvey, 2018; Grant, 1996; Foss & Pedersen, 2019).

Second, educated workers are more adept at anticipating and understanding customers’ changing needs, preferences, and pain points. This is a crucial ability for identifying new opportunities and tactics to boost performance in innovation (Barth et al., 2018; Teece, 2018; Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004).

Third, they are better at identifying cost-saving opportunities and seeking funding sources to support innovation initiatives. They are also more capable of managing the financial risks associated with innovation by employing sophisticated financial analysis and modeling techniques (Teece, 2018).

Fourth, they are able to create wider social and professional networks, including ties to businesses, academic institutions, and research centers. These networks can offer more resources and experience to help get past challenges (Cohen & Levinthal, 2000; Leiponen, 2005).

Finally, an educated workforce promotes a mindset of continuous learning and improvement. This helps companies improve their innovation processes over time and more easily adopt new methods and technologies, as they are more aware of new trends and developments (Argyris & Schön, 1997; Bresnahan et al., 2002; Ciriaci et al., 2016). According to Toner (2011), skills also have network externalities. This means that each worker's productivity is increased both by their own skill level and by the average skill level of their coworkers.

Based on these points, more skill-intensive firms are expected to be better able to drive successful innovation efforts and overcome barriers to innovation, as found in this article.

Our results further highlight that skill intensity becomes crucial when firms face significant obstacles. For firms without obstacles, skill intensity does not influence the likelihood of innovation. This finding expands upon earlier research that suggests that skills act as a contingency factor rather than a universal driver of innovation. By distinguishing between firms with and without obstacles, this study offers a nuanced perspective, underscoring that a skilled workforce can help firms unlock their innovation potential under adverse conditions.

Theoretical contributions and implicationsThis research offers several contributions to the theoretical understanding of innovation obstacles and the role of skills. First, it integrates the concept of endogenous obstacles into the analysis of innovation. This addresses a gap in the existing literature, as the non-random nature of facing obstacles has been underexplored. By employing a switching model that simultaneously estimates the likelihood of facing obstacles and the likelihood of innovation, we are advancing the theoretical approaches to studying firm-level innovation processes.

Second, our findings refine the understanding of the role of human capital in innovation. While prior studies often focused on the direct link between education and innovation outcomes (Kromann & Sørensen, 2024), we demonstrate that the value of education is especially important in the presence of obstacles. We also identify the relative importance of business education in overcoming challenges, suggesting that different educational backgrounds contribute unequally to firms’ problem-solving capacities. This extends the existing theories of skill heterogeneity and their application in organizational contexts.

Finally, this study contributes to the broader conversation about trade-offs in innovation management. It highlights the nuanced relationship between workforce composition and innovation effectiveness, offering theoretical insights into how firms can balance costs and benefits in their human resource strategies.

Implications for practicesInnovation success for businesses is more crucial than ever in today's competitive business world. Consequently, management may search for strategies to successfully create and implement new ideas. This study therefore has great value, as it sheds light on methods for overcoming innovation obstacles. Our findings thus emphasize the importance of strategic workforce planning for firms that aim to enhance their innovation capabilities. Firms that face significant obstacles should prioritize skill development or hire employees with higher levels of education. This is particularly important in fields such as business, which our analysis identifies as especially valuable for navigating diverse innovation challenges. Managers should recognize that skill intensity is most impactful in adverse conditions, suggesting that investment in education yields the highest returns when obstacles are present.

The study also provides actionable insights into cost-effective workforce strategies. While hiring highly educated workers may seem financially burdensome, our findings indicate that short-cycle tertiary education workers can be particularly effective in overcoming obstacles. This insight can guide firms that are concerned about the trade-offs between labor costs and innovation performance, as they can achieve significant benefits without always resorting to hiring workers with longer and costlier educational backgrounds.

These findings also underline the importance of fostering collaboration between skilled employees and other resources. Firms should consider pairing their human capital investments with external R&D collaborations, customer partnerships, or supplier networks, all of which have been shown to amplify the benefits of a skilled workforce. Managers may also consider training programs targeted at improving the problem-solving capabilities of employees in critical areas such as market analysis and process management.

For policymakers, these findings underscore the need to support educational programs that align with industry needs, particularly in the case of short-cycle tertiary education. By equipping firms with the skilled workforce, they require to navigate challenges, public policies could indirectly support innovation. These policies would be aimed at reducing barriers to skill acquisition and at fostering collaboration between firms and educational institutions.

Limitations and future research directionDespite its contributions, this study has several limitations that future research could address. First, our empirical strategy accounts for potential biases (e.g., selection, simultaneity, and omitted variables). However, by exploiting the structure of our longitudinal survey data matched with registry data, more definitive causal inference could possibly be obtained by using a suitable natural experiment. Future studies could employ field experiments or larger panel datasets to enhance causal understanding.

Second, the dichotomic nature of the dependent variable restricts our analysis to asking whether firms innovate without capturing the scope or magnitude of innovation. For example, we cannot determine the number of new products or services being introduced, the share of sales from these new innovations, or the scale of process improvements. Research that leverages datasets with more granular innovation metrics could offer deeper insights into the link between skill intensity and innovation outcomes.

Third, our study does not differentiate between the stages of the innovation process in which obstacles occur. Understanding whether barriers emerge during the ideation, development, or commercialization phases would provide actionable insights for managers and policymakers. Future studies could explore this dimension by integrating data on the timing and types of obstacles.

Fourth, a larger dataset would allow for a more detailed analysis to uncover the differential impacts of various obstacle types within industries. It would be similarly interesting to examine workforce diversity within firms in more detail. This could be done qualitatively by conducting targeted interviews.

Finally, more detailed information on the resources used to overcome obstacles could refine our understanding of how firms allocate investments to address challenges. For instance, exploring how firms balance internal capabilities with external partnerships in navigating barriers could be a valuable extension of this research.

ConclusionThis article adds to the existing literature on innovation by discussing whether a more educated workforce can help firms overcome obstacles to innovation while also acknowledging that facing obstacles is not random.

Our findings provide strong evidence that companies with higher skill intensity are better able to overcome obstacles when it comes to achieving their innovation goals. This holds true for manufacturing and service companies, high-tech and low-tech firms, and small and large businesses. This also holds true regardless of the type of innovation (product, service, or process) and, to a certain degree, the type of barriers (money, knowledge, and market) that businesses encounter. When distinguishing between different educational fields, business education is found to be especially valuable at overcoming obstacles to all types of innovation compared to technical or other educational backgrounds.

The above findings suggest that firms should carefully consider the trade-offs between the costs of hiring more expensive educated workers and the benefits of having a higher chance of achieving innovation. Our analysis reveals that workers with short-cycle tertiary educations have a greater impact on the likelihood of being innovative when faced with obstacles than workers with longer cycles. This suggests that hiring more costly workers with medium- or long-cycle tertiary educations is not necessary for firms that are worried about the higher cost of hiring educated workers. However, diversity in educational length within a firm positively impacts the firm's likelihood of being innovative when it faces obstacles.

CRediT authorship contribution statementBenoit Dostie: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Formal analysis. Lene Kromann: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation. Anders Sørensen: Writing – review & editing, Resources, Funding acquisition.

1.1 Survey questions regarding innovation activities

Questions used for the different types of innovation for the 2018 survey.

Product innovation:

Service innovation:

Process innovation:

We construct three dummy variables that take value 1 if at least one of the questions within the specific innovation type (product, service or process innovation) is answered yes. Otherwise, the value is 0, implying that the firm's answer is no to all specific innovation type questions. Lastly, we construct an overall innovation dummy that takes value 1 if at least one of the questions across the innovation types is answered with a yes. Otherwise, the value is 0.

For the period 2006–2016 the following questions defined process, organizational and marketing innovation (they were combined into process innovation in the 2018 survey):

Process innovation:

Organizational innovation:

Marketing innovation:

1.2 Control variables

Table A1 provides summary statistics for control variables included as determinants of innovation.

Definition and mean (sd) for control variables included in the innovation equation.

Notes: *The HH index is calculated as the sum over industry of the square of the sales in Denmark within a firm divided by the total sales within the industry in Denmark. An industry is defined here as the 6-digit industry code. An industry with many small firms has a value closer to 0 (perfect competition), while a monopolistic producer has a value of 1. Increases in the HH index indicate a decrease in competition and an increase in market power.

Definition and mean (sd) for extra control variables included in the obstacle equation.

Notes: * The Lerner index is calculated as 1 minus the mean within an industry of results divided by sales. Values of 1 indicate perfect competition, while values below 1 indicate some degree of market power. The Lerner index is therefore more about how close a market is to performing competitively defined as how much a firm earns from its products (profit margin), while the HH index, which is included as control variable in the innovation regression, is more about the distribution of market shares within a given industry.

Likelihood of being innovative across innovation and obstacle types.

Likelihood of being innovative for different innovation types depending on faced obstacles and skill intensity.

Coefficient estimates for the selection equation in the endogenous switching model in Table 6.

Notes: See Table 6.

Endogenous switching regression model: coefficient estimates from the innovation equation.

Notes: See Table 6. The base group consist of 57 firms – 29 innovative firms and 28 that are not innovative.

Robustness check of Table 6.

| Innovation | Full sample | Innovations in 2008–2018 | Other obstacle definition | Other obstacle definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No obstacles: Skill intensity | .06 (.10) | .10 (.12) | .10 (.08) | .10 (.13) |

| Facing obstacles: Skill intensity | .25***(0.07) | .15*** (0.07) | .32***(0.11) | .24*** (0.07) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control variables included | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| # of firms | 2524 | 2027 | 2223 | 2223 |

Notes: The estimation method used, and the control variables included are the same as in Table 6. In the first column we did not delete firms that are not willing to innovate, as is common in the literature and done in Table 6. In the second column, instead of using the criteria in Table 6, we deleted firms that did not report innovations in the period 2008–2018, given they were included in the survey. In column 3, as in D'Este et al. (2014), we defined firms as facing obstacles if they answered that at least one of the obstacles were of great importance, whereas Table 6 also lists firms as facing obstacles if they to at least one of the obstacle questions answered, “somewhat important”. In column 4, we defined firms that face obstacles as those that at least to one of the obstacle questions answered that it was of great, some or low importance. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

Summary statistics of the dependent variable in the selection equation in Table 9.

Obstacle types and education types.

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. Firms that only face obstacles other than the one in focus in the column were removed from the sample. For example, for column 1, we deleted firms that only face obstacles other than money/financial obstacles. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

Obstacle types and education length.

Notes: The estimation method used, and control variables included are the same as in Table 6. Firms that only face obstacles other than the one in focus in the column were removed from the sample. For example, for column 1, we deleted firms that only face obstacles other than money/financial obstacles. * Indicates that the coefficient is significant at the 10 % significant level, ** at the 5 % significant level and *** at the 1 % significant level.

The sample was stratified by firm size, industry, and past R&D expenditure (both level and variance). These variables are included as regression controls.

Savignac (2008) and Blanchard et al. (2013) showed in their studies that the effects of obstacles on innovation performance were sensitive to sampling decisions, with the coefficients turning negative only when the non-innovators were excluded.

The industry classification being used is DB07, which is the national version of the EU's nomenclature (NACE). The first four digits refer to NACE rev. 2, while the last two represent the Danish subdivision. Industries are defined at the six-digit level.

HHI involves the distribution of market shares within an industry, while the Lerner index focuses more on how much money a firm makes on their products (profit margin). We believe that firms operating in markets with high HHI (less competition) are more likely to innovate, but this does not affect whether the firm faces obstacles. However, low profit margins (high Lerner index) are believed to influence whether firms face obstacles, especially in the case of money and financial obstacles.