Green innovation serves as a pivotal approach to address environmental challenges and drive sustainable economic development. Using a sample of companies listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen A-share markets from 2003 to 2024, this study empirically examines how conglomerates affect corporate green innovation. The results show that conglomerates significantly enhance green innovation—particularly in enterprises located in regions with stricter environmental regulations and those with executives possessing stronger environmental awareness. Mechanism tests reveal that the alleviation of “financing constraints” through the internal capital market and the compensation for “knowledge gaps” through the internal knowledge network are key channels through which conglomerates drive green innovation within their member enterprises. These findings not only contribute to the literature on the role of conglomerates in environmental governance but also provide valuable insights for promoting the green transformation and sustainable development of enterprises.

Green innovation is a critical driver of carbon emission reduction and sustainable development. Enterprises, as the primary consumers of natural resources and major carbon emitters, occupy a central role in green innovation. Therefore, determining how to effectively promote green innovation has become an urgent concern. Existing studies on the drivers of green innovation have focused on individual firms, often overlooking the impact of conglomerate organizational structures. A conglomerate is an organizational structure composed of numerous legally independent enterprises, with a pyramid hierarchy based on equity ownership being its predominant form (Khanna & Yafeh, 2007). As a common business form, conglomerates are widespread not only in developed countries such as Germany and Japan but also in emerging economies such as Turkey and Thailand. In China, conglomerates form the backbone of privately listed enterprises. With the ongoing deepening of State-owned enterprise reforms, State-owned conglomerates are also continuously expanding. Therefore, we examine the impact of conglomerates on green innovation and its underlying mechanisms, which is crucial for enhancing green innovation.

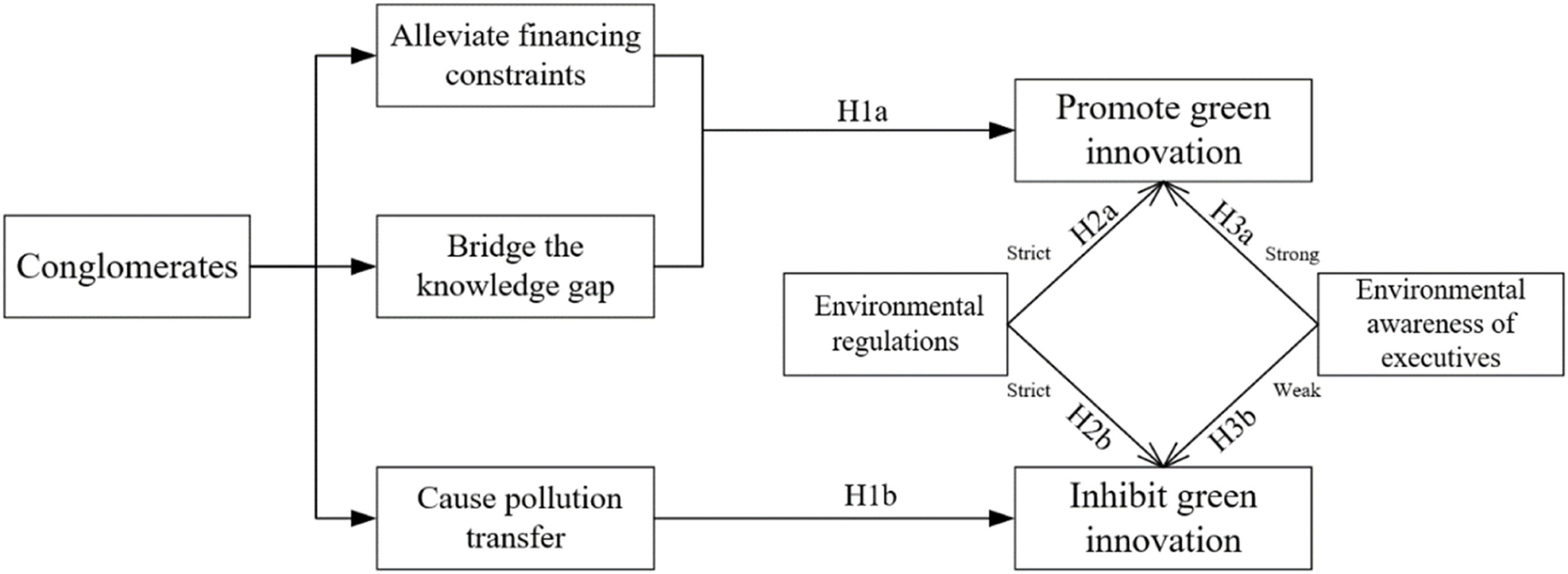

Compared with individual enterprises, conglomerates can establish internal capital markets and internal knowledge networks, providing member enterprises with long-term and stable financial support for investments in green innovation and diverse knowledge on cutting-edge low-carbon technologies, thus helping to promote green innovation of member enterprises. However, conglomerates may also provide member enterprises with room for internal pollution transfer, which further aggravates the “insufficient incentives” for green innovation and inhibits green innovation. Therefore, whether conglomerates can alleviate financing constraints and knowledge shortcomings through internal capital markets and internal knowledge networks and, thus, improve or inhibit enterprise green innovation through internal pollution transfer remains an untested empirical question.

The numerous conglomerates unique to China provide fertile research ground for investigating the effect of conglomerate organizational forms on green innovation. On the one hand, in emerging market economies, the pyramid structure derived from conglomerates can be used as an alternative protection mechanism to reduce government intervention in enterprise operations (Fan et al., 2013). Consequently, China has a fairly large number of conglomerates compared to other countries. On the other hand, China has maintained a State-dominated financial system, with the government overseeing the allocation of financial resources in both the banking sector and the securities market. This government-guided allocation of financial resources tends to favor a select group of large State-owned enterprises that are vital to the country’s economic development and the growth of specific regions. However, securing financing through the State-controlled financial system is a challenge for most non-State-owned enterprises, which often experience significant financial disincentives. In such cases, conglomerates can serve as internal capital markets, helping to alleviate the financial constraints experienced by private enterprises.

Our examination of the impact of conglomerates on corporate green innovation in China reveals that conglomerates significantly promote corporate green innovation. This effect is pronounced in enterprises in regions with higher environmental regulatory intensity and those with executives with higher environmental awareness. The mechanism test reveals that the financing difficulties alleviation of the internal capital market, as well as the knowledge spillover effects of the internal knowledge network, are important channels for conglomerates to promote green innovation among member enterprises.

Our study makes the following contributions. First, we examine the impact of organizational linkages on member enterprises’ green innovation from the perspective of the organizational form of conglomerates, which further enriches the research related to the precedent conditions of enterprises’ green innovation. In-depth discussions about the influencing factors of green innovation have been conducted at the macro- and micro-level, focusing on environmental regulatory policies (Fang et al., 2021), corporate culture (Sengüllendi et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2024), corporate resource capabilities (Xie & Wang, 2025; Zhang et al., 2025), and executive characteristics (Jian et al., 2024; Yang & Liu, 2023) while ignoring the influence of group organizational forms. Second, we enrich the research on the environmental governance effects of conglomerates from the perspective of green innovation. Existing studies have focused on examining the financial characteristics of conglomerates, including operating advantages (Siegel & Choudhury, 2012; Hamelin & Lefebvre, 2025), Financing efficiency (Buchuk et al., 20l4; Almeida et al., 2015), and market valuation (Ducret & Isakov, 2024). However, research on the effectiveness of environmental governance of conglomerates needs to be supplemented. As a key component of environmental strategy, enterprise green innovation can well reflect the environmental governance effect of the enterprise. Third, the research findings have important implications for policy-makers and enterprises. Our findings reveal that conglomerates can promote green innovation, which is intimately related to external environmental regulation and the internal environmental awareness of corporate managers. Therefore, policy-makers should encourage the development of conglomerates and support merging and reorganization among enterprises, per market-oriented principles. They should also promote environmental regulations. Enterprises should form executive teams that possess keen environmental awareness to fully exploit the internal capital market and internal knowledge network of the conglomerate to foster green innovation.

Literature review and research hypothesesEconomic consequences of conglomeratesEnterprise groups, as a type of economic organization that straddles the market and the single enterprise, have attracted significant academic attention, and numerous studies have confirmed the advantages of group-affiliated operations. First, regarding production and operation, conglomerates efficiently organize production for a variety of resource inputs and respond relatively positively to industry shocks (Siegel & Choudhury, 2012). Member firms exhibit a greater number and variety of competitive actions (Kumar & Manikandan, 2024). Additionally, group-affiliated firms invest in more profitable projects after IPO and recover faster during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Larrain et al., 2021; Hamelin & Lefebvre, 2025). Second, regarding financing activities, existing research indicates that the funding recipients within business groups are typically small-scale, high-growth, and capital-intensive firms. After receiving funding, these firms show improved operational performance, confirming the greater efficiency of the group’s internal capital market (Buchuk et al., 2014; Almeida et al., 2015). Kabbach-de-Castro et al. (2022) indicated that when business groups experience financing constraints, the internal capital market allocates funds to firms with better external financing capabilities, thereby enabling larger-scale investments. Moreover, groups provide support to subsidiaries in financial distress to prevent internal bankruptcies (Beaver et al., 2024). Third, in terms of market valuation—owing to compensating for the deficiencies in the external capital, labor, and technology markets—business groups demonstrate significantly better accounting performance and stock returns compared to standalone firms (Khanna & Palepu, 2000). Ducret and Isakov (2024) identified that firms affiliated with large, financially stable, and well-performing business groups are accorded higher valuations. Finally, regarding social responsibility, group-affiliated firms exhibit better corporate social responsibility performance than non-group firms and are less likely to misreport (Choi et al., 2019; Ahn et al., 2025). Kim and Lee (2024) indicated that when business groups have stronger political connections, the probability of committing financial fraud decreases.

However, contrasting research findings do exist. First, business groups suffer from significant agency problems, leading to the prevalence of tunneling behavior (Purkayastha et al., 2022). The controlling shareholder expropriates the interests of minority shareholders through tunneling activities, such as transferring benefits from affiliates where they have lower cash-flow rights to those with higher cash-flow rights, as well as through mergers and acquisitions (Bae et al., 2002; Bertrand et al., 2002). Owing to the existence of tunneling, affiliated firms have significantly higher bond issuance interest rates than unaffiliated firms (Cheng et al., 2022), and experience declining operating performance (Bertrand et al., 2008). Uddin et al. (2024) suggested that the board independence of group-affiliated firms is lower than that of standalone firms, which impedes their financial performance. Furthermore, group affiliation may inhibit member firms’ organizational innovation performance and entrepreneurial orientation (Min et al., 2022; Purkayastha & Gupta, 2023). Second, several studies have identified pollution transfer behavior within business groups. Chen et al. (2025) discovered that in the context of stringent environmental regulations, firms tend to reduce their own output and shift some production to unregulated firms within the same business group, rather than improving their energy efficiency. Dechezleprêtre et al. (2022) investigated pollution transfer within multinational corporate groups and identified that multinational corporations operating in multiple countries tend to shift production to countries with weaker regulations in response to higher environmental regulatory costs in certain countries. Generally, abundant research on conglomerates exists, but the issue of advantages and disadvantages of conglomerations remains controversial. Furthermore, research on the operation of conglomerates from the viewpoint of green innovation remains scarce.

Factors influencing green innovation in enterprisesGreen innovation, as a key support for achieving low-carbon transformation, has become a focal point of academic attention. However, there exists no consensus regarding the definition of green innovation. Hemmelskamp (1997) defined this concept as an innovative activity that prevents or reduces environmental burdens, addresses environmental damage, or diagnoses and monitors environmental issues. Rennings (2000) further expanded the connotation of green innovation, proposing that any behavior capable of decreasing environmental pollution or reducing environmental burden should be regarded as green innovation. A few scholars define green innovation as an innovative practice that adheres to the concepts of ecological design and ecological manufacturing, using environmentally friendly raw materials in the design and manufacturing process of products, and developing sustainable products and processes (Albort-Morant et al., 2016; MacDonald & She, 2015). They emphasize that green innovation is a systematic innovation throughout the entire business cycle, covering the whole process of product design, production, supply, and end-use (Takalo et al., 2021). Oltra and Jean (2009) also hold that any innovation that can benefit the environment and promote environmental sustainability belongs to green innovation, including process, practice, system and product innovation. The World Intellectual Property Organization has proposed the broadest definition, bringing pollutant treatment technologies, technologies for delaying climate change, and green management innovations, all within the scope of green innovation.

Nevertheless, the definitions of green innovation share certain commonalities. Existing literature generally agrees that the core objective of green innovation is to mitigate the adverse impact on the environment, promote sustainable development, and achieve a balance between economic benefits and environmental–ecological benefits. Moreover, the forms of green innovation are diverse, involving multiple dimensions such as products, processes, technologies, services, and management. Based on this, and drawing on the definition by Ben Arfi et al. (2018), this study argues that green innovation is an innovative activity undertaken by enterprises with the goal of sustainable development and environmental protection, achieved through product-technology upgrades and process optimization. It encompasses various aspects such as energy conservation, pollution prevention and control, waste recycling, green product design, and corporate environmental management.

Regarding the driving factors of corporate green innovation, existing research has primarily focused on two factors: external environmental regulations and firm-specific characteristics. While traditional environmental economics suggests that stricter environmental regulations increase enterprise costs, thereby reducing their investment confidence, Porter and Linde (1995) argued that environmental regulations can not only improve environmental outcomes but also enhance resource utilization efficiency within enterprises. They concluded that such regulations enable firms to identify and utilize the opportunities presented by green innovation. Given the complexity of environmental policy institutions and the diversity of regulatory tools, environmental regulations are categorized into three main types: command-and-control, market-based incentives, and public participation (Huang et al., 2016). Command-and-control regulations are characterized by direct government administrative controls, such as mandatory emission reduction targets and standards imposed on enterprises. Fang et al. (2021) noted that these direct administrative controls create positive incentives for companies to engage in green innovation. Market-based environmental regulations, such as carbon emissions trading, sewage fees, and government spending on environmental protection, also play a crucial role. Calel and Dechezleprêtre (2016) identified that carbon emissions trading in the European Union (EU) significantly boosts corporate green innovation, increasing EU patents for green technologies by at least 10 %. Regarding sewage fees and fiscal expenditure on environmental protection, research shows that both can effectively promote corporate green innovation (Ren et al., 2021; Li & Gao, 2022). According to the stakeholder theory, public participation-based environmental regulations primarily influence corporate green innovation (Li et al., 2023).

From the perspective of firm-specific characteristics, first, organizational form influences corporate green innovation performance. Existing studies have indicated that owing to motivations to maintain decision-making control and risk aversion, family firms exhibit lower willingness for green innovation compared to non-family firms (Aiello et al., 2021). Conversely, green strategic alliances between firms encourage them to undertake greater risks, thereby facilitating green innovation (Wang et al., 2025). Government–university–industry alliances enable the sharing of capabilities and resources among different entities, providing crucial support for green innovation (Yang et al., 2021). Digital alliances support firms to access knowledge of advanced information systems, which can also promote green innovation (Bendig et al., 2025). Second, corporate culture and attitudes are key factors affecting green innovation.Ethical leadership contributes to the development of a green organizational culture, thus promoting green innovation (Sengüllendi et al., 2024). Competitive culture also incentivizes firms to increase environmental investment and improve green innovation performance (Tian et al., 2022; Akhtar et al., 2024). In the context of China, traditional Confucianism positively influences innovation by curbing managerial myopia and improving employee-related corporate social responsibility (Huang et al., 2024). However, clan culture reinforces the controlling family’s preference for family control, thereby inhibiting green innovation (Yan et al., 2025). Third, an enterprise’s resource capabilities, financing, and governance mechanisms can also impact its green innovation performance. Digital transformation and digital capabilities facilitate corporate financing and collection of environmental information, thereby promoting green innovation (Zhang et al., 2025; Xie & Wang, 2025). Issuing green bonds can also enhance both the quantity and quality of corporate green innovation (Lian et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2022). Green investors can enhance executives’ green perception while site visits by institutional investors ensure external monitoring—both can foster corporate green innovation (Tang et al., 2024; Wang, 2025). Additionally, studies have examined the influence of corporate management. Myopic behavior by top managers inhibits green innovation, whereas an relevant academic background helps promote it (Jian et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Managers’ environmental awareness also positively impacts a company’s engagement in green innovation (Yang & Liu, 2023). This environmental awareness encompasses both managers’ environmental risk awareness and cost–benefit awareness. Environmental risk awareness refers to the management’s recognition of potential adverse effects that the enterprise may have on the environment. The greater the managers’ awareness of environmental risks, the more likely they are to promote green innovation owing to a sense of social responsibility or profit-seeking motives, thereby reducing the firm’s adverse environmental impact (Gadenne et al., 2009; Kassinis et al., 2016). Environmental cost–benefit awareness refers to the management’s recognition of the cost advantages deriving from superior environmentally friendly practices. Managers with this awareness will focus more on improving existing product lines and developing green products with shorter payback periods and higher visibility (Peng & Liu, 2016). While the existing literature provides a solid theoretical foundation for exploring the drivers of corporate green innovation, the role of conglomerates as an internal driver of green innovation remains underexplored.

Research hypothesesGreen innovation, as an enterprise environmental strategy, is a complex process of continuity and accumulation with an extended cycle and high risk (Quan et al., 2023). Unlike general environmental protection investments, green innovation must focus on addressing challenges in three key areas. First, the financing constraint of green innovation, which involves long-term and high-intensity environmental protection investments. To address this, green innovation must first secure adequate financial support. Owing to the inherently high risks, uncertainties regarding inputs and outputs, many green innovation projects often experience challenges in securing follow-up funding (Huang et al., 2019). Second, the knowledge gap in green innovation. Green innovation requires advanced technologies, knowledge, and skills to address environmental pollution, yet solving environmental issues is not typically the core focus of most enterprises. Thus, acquiring the complex technologies and knowledge necessary for green innovation from within the enterprise becomes challenging (Ben Arfi et al., 2018). Third, insufficient incentives for green innovation. Owing to the externalities associated with green innovation activities and the extended time-frame between “green innovation inputs, outputs, and returns,” enterprises often lack the necessary incentives to invest in green innovation (Li et al., 2023).

Conglomerates can address two major challenges: financing constraints and knowledge gaps, thereby promoting green innovation within enterprises. To overcome financing constraints, conglomerates can leverage the “more money” and “living money” effects of their internal capital markets, encouraging member enterprises to invest in long-term green R&D. By establishing financial enterprises, conglomerates can create internal capital markets to facilitate deposits, loans, settlements, and mutual fund transfers. The effectiveness of conglomerates’ internal capital markets is well-supported by extensive empirical evidence (He et al., 2013). On the one hand, a conglomerate’s internal capital market can enhance the financing capacity of its member enterprises, both by providing direct financial support and by helping them access external capital markets through guarantees. On the other hand, conglomerates can lower financing costs for member enterprises, as shown by the credit services in their Financial Service Agreements, which are priced below domestic commercial bank loan rates.

Considering the knowledge-gap issue, conglomerates can foster information sharing and knowledge spillover within their internal knowledge networks, facilitating the flow of knowledge required for green innovation activities among member enterprises. By establishing R&D subsidiaries, conglomerates can create internal knowledge networks to optimize the allocation of innovation resources within the group. R&D subsidiaries—with their unique advantages in research and development—are more likely to establish connections with research institutions and universities, offering multiple channels for member enterprises to access information, thereby supporting their green innovation efforts. Additionally, the internal knowledge network can help shorten the R&D cycle for green technologies and accelerate green innovation outcomes by leveraging, learning from, and imitating the diverse knowledge.

Notably, conglomerates address the challenge of financing constraints through internal capital markets and mitigate the issue of knowledge shortage through internal knowledge networks, thereby fostering green innovation within their enterprises. Based on this, the following research hypothesis is proposed:

H1a Enterprises affiliated with conglomerates exhibit higher levels of green innovation compared to independent enterprises.

Conglomerates may exacerbate the issue of “insufficient incentives,” thereby hindering corporate green innovation. Conglomerates provide space for pollution transfer from member enterprises. Studies have indicated that pollution transfer is a challenge for enterprises with multiple plants and conglomerates with multiple equity affiliates. When an enterprise with multiple factories is subject to environmental regulation, the enterprise will alleviate the pressure of environmental regulation by transferring production activities to unregulated factories. When a plant is subjected to strict environmental regulation, pollution emissions from unregulated plants within the same enterprise increase significantly (Gibson, 2019). Therefore, conglomerates can capitalize on differences in environmental regulation between regions by shifting highly polluting production activities to enterprises within the same conglomerate with weaker environmental regulations. Consequently, conglomerates can cope with environmental regulations through pollution transfer, and the incentive to undertake green innovation activities is attenuated. Accordingly, we propose the following research hypothesis:

H1b Enterprises affiliated with conglomerates have lower levels of green innovation than independent enterprises.

The impact of conglomerates on green innovation may vary depending on regional environmental regulation. In regions with lower environmental regulatory pressure, enterprises experience fewer incentives to pursue green transformation (Li et al., 2023). In such cases, there may be little to no difference in the level of green innovation between independent enterprises and those that belong to a conglomerate. Conversely, in regions with stricter environmental regulations, enterprises have stronger incentives to adopt green transformation to meet legitimacy requirements. In this context, if the dual effects of capital markets and internal knowledge networks within the conglomerate prevail, subsidiary enterprises are likely to exhibit higher levels of green innovation. However, if pollution transfer within the conglomerate takes precedence, subsidiary enterprises may show lower levels of green innovation than independent enterprises. Based on this, we propose the following opposing hypotheses:

H2a In regions with stricter environmental regulations, conglomerates exert a stronger promoting effect on green innovation.

H2b In regions with stricter environmental regulations, conglomerates exert a stronger suppressive effect on green innovation.

The impact of conglomerates on green innovation may vary depending on the environmental awareness of executives. Enterprises whose executives exhibit low environmental awareness lack the intrinsic motivation to engage in green innovation activities (Wang et al., 2021). In such cases, executives of affiliate firms within a conglomerate are more likely to exploit the conglomerate structure for internal pollution transfer, leading to a lower level of green innovation compared to standalone listed companies. In contrast, enterprises with executives who possess stronger environmental awareness are more intrinsically motivated to pursue green and low-carbon transformations. These executives can leverage the internal capital market to secure long-term, stable, and low-cost financial support for green innovation, while also utilizing the internal knowledge network to absorb diverse, cutting-edge knowledge essential for driving green innovation. Based on this, we propose the following opposing hypotheses:

H3a In enterprises led by executives with stronger environmental awareness, the promoting effect of conglomerates on green innovation is stronger.

H3b In enterprises led by executives with weaker environmental awareness, the inhibitory effect of conglomerates on green innovation is stronger.

Fig. 1 illustrates the relationships between the hypotheses.

Research designSamples and dataThis study takes the annual observations of all Chinese A-share listed companies on the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges from 2003 to 2024 as the initial sample. The year 2003, when conglomerate data disclosure commenced, is chosen as the starting point. Observations from financial industries and those with missing data for the variables are excluded, resulting in 51,053 firm-year observations. Green patent data are drawn from the China Research Data Service Platform (CNRDS). All other data are drawn from the China Securities Market Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). All continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st percentile to mitigate potential influence of outliers.

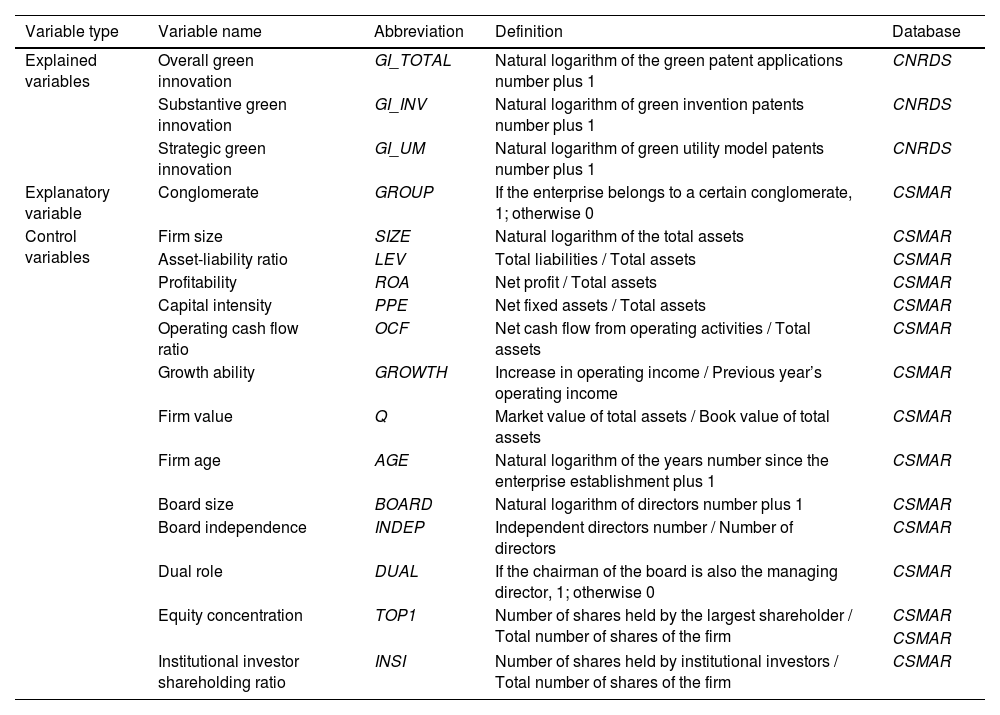

Definition of variablesOur explained variable is corporate green innovation. According to Quan et al. (2023), green innovation of enterprises is measured based on three indicators. First, the overall green innovation level of enterprises (GI_TOTAL), which is equal to the natural logarithm of the green patent applications number plus 1. Second, the substantive green innovation level of enterprises (GI_INV), which is measured as the natural logarithm of green invention patents number plus 1. Third, the strategic green innovation level (GI_UM), which equals the natural logarithm of green utility model patents number plus 1.

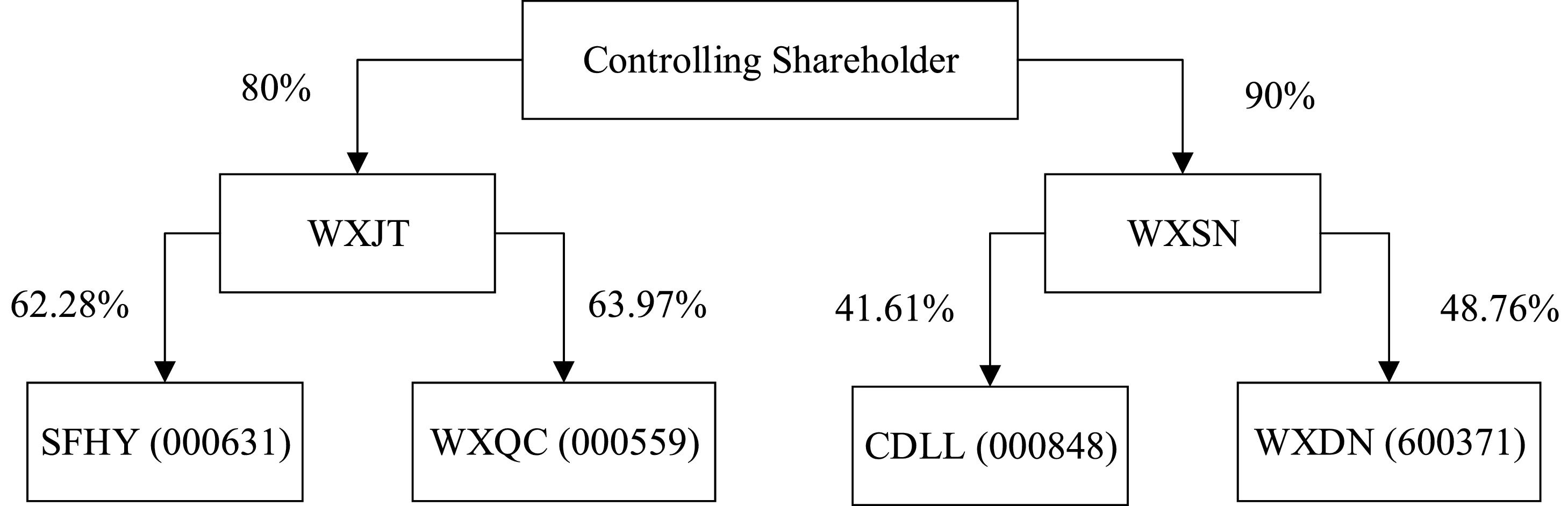

Our explanatory variable is a dummy variable for conglomerate (GROUP), which equals 1 if a listed company is affiliated with a conglomerate, and 0 otherwise. Regarding the definition of a conglomerate, if two or more listed companies share the same ultimate controlling shareholder in a given year, they are affiliated with the same conglomerate; otherwise, they are classified as standalone firms (He et al., 2013). Based on this criterion, we identify the ultimate controlling shareholder by examining the chain of ownership control diagrams. Fig. 2 illustrates a typical organizational structure of a business group.

In Fig. 2, the number on the arrow denotes the shareholding percentage; the capital letter within the box represents the abbreviation of the listed company; and the number in parentheses is the company’s security code. Listed companies SFHY, WXQC, CDLL, and WXDN share the same ultimate controlling shareholder. Therefore, they are defined as member firms of a business group in this study. Accordingly, the GROUP dummy variable is assigned a value of 1. Conversely, if a listed company is independent—that is, it shares no common ultimate controlling shareholder with any other listed company—the GROUP variable is assigned a value of 0. Table 1 presents the control variables.

Definitions of variables.

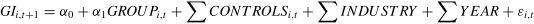

Hypothesis H1 examines the impact of business groups on corporate green innovation. To test H1, we employ panel data regression while controlling for both industry and year fixed effects, and construct the following fixed effects model:

Where GI denotes enterprises’ green innovation level, GROUP denotes whether the enterprise belongs to a certain corporate group, CONTROLS denotes control variables, and INDUSTRY and YEAR represent industry fixed effects and year fixed effects, respectively. Industry fixed effects are employed to control for the influence of industry characteristics on corporate green innovation. Year fixed effects are included to account for macro-economic factors occurring in specific years that may impact firms’ green innovation.Hypothesis H2 examines the moderating effect of regional environmental regulation on the relationship between business group affiliation and corporate green innovation. To test H2, we further add the intersection term of environmental regulations and enterprise groups on the basis of Model (1), and construct the following fixed effects model:

In model (2), ER represents the environmental regulation intensity of the province where the listed company is located. It is calculated as the natural logarithm of the provincial environmental administrative penalty cases number plus 1. A higher value indicates greater external environmental regulatory pressure on the listed company. Our main concern is the coefficient β₃ of the interaction term GROUP × ER. It captures how the impact of business group affiliation on corporate green innovation varies under different levels of regional environmental regulatory pressure.

To test Hypothesis H3, which examines the moderating effect of executives’ environmental awareness on the relationship between business group affiliation and corporate green innovation, we extend model (1) by incorporating an interaction term between executives’ environmental awareness and business group affiliation. The following fixed-effects model is specified:

In Model (3), ENV represents executives’ environmental awareness. It is proxied by a dummy variable indicating whether the top management team has an educational or professional background related to environmental protection. Specifically, an executive is identified as having environmental protection experience if their résumé contains keywords such as “environment,” “environmental protection,” “new energy,” “clean energy,” “ecology,” “low-carbon,” “sustainability,” “energy conservation,” and “green.” Our main concern is the coefficient θ3 of the interaction term GROUP × ENV, which captures how the effect of business group affiliation on corporate green innovation varies depending on the level of executives’ environmental awareness.

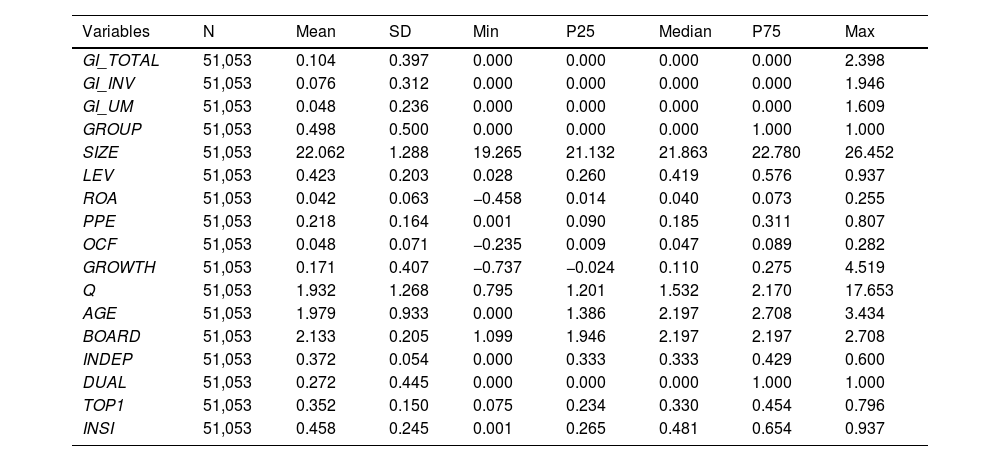

Empirical analysisDescriptive statisticsTable 2 presents the data summary. The average values of enterprises’ green innovation level (GI_TOTAL, GI_INV, GI_UM) are 0.104, 0.076, and 0.048, and the corresponding standard deviations are 0.397, 0.312, and 0.236, respectively. These results indicate significant variation in the green innovation levels across the sample enterprises. The average value of the conglomerate variable (GROUP) is 0.498, indicating that 49.8 % of enterprises belong to conglomerates.

Descriptive statistics.

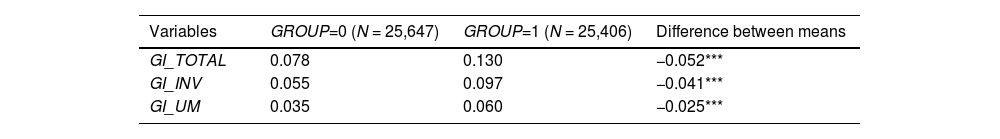

Table 3 reports the test for differences in green innovation in the subsamples of conglomerate member enterprises and independent enterprises. For the subsample of conglomerate member enterprises, the mean values of GI_TOTAL, GI_INV, and GI_UM are 0.130, 0.097, and 0.060, respectively, which are significantly higher than the mean values of the subsample of independent enterprises. Based on this, we can initially judge that the organizational form of conglomerates can promote enterprise green innovation.

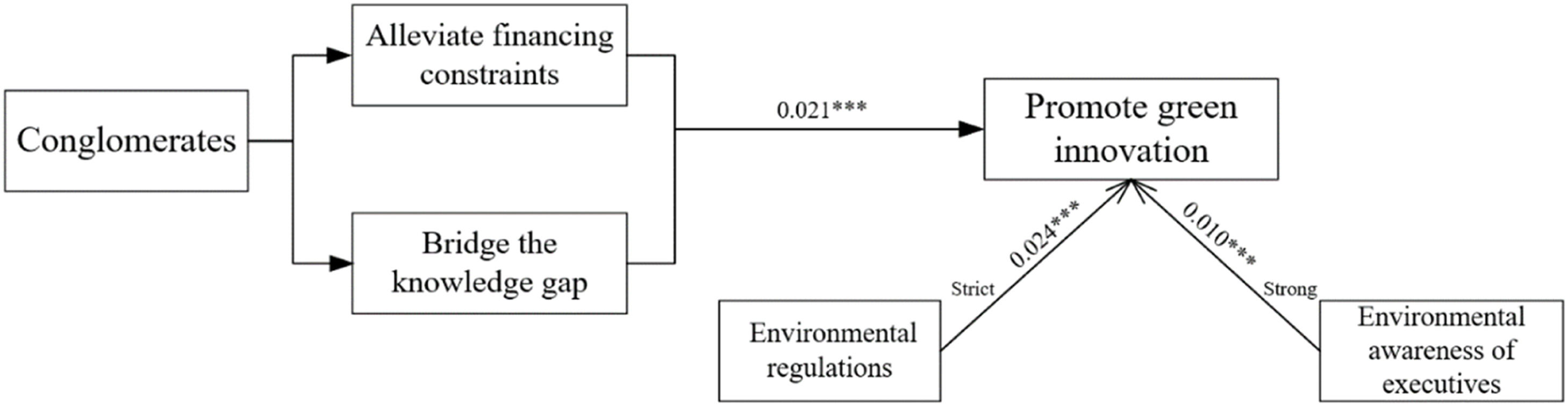

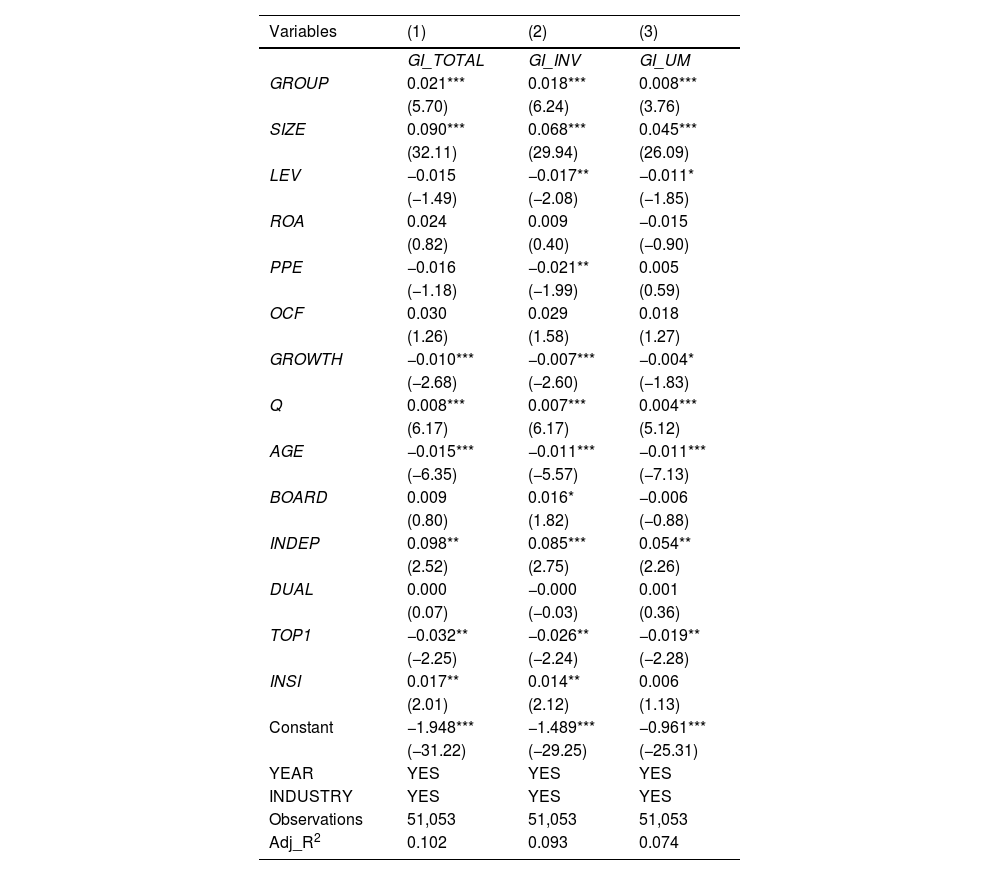

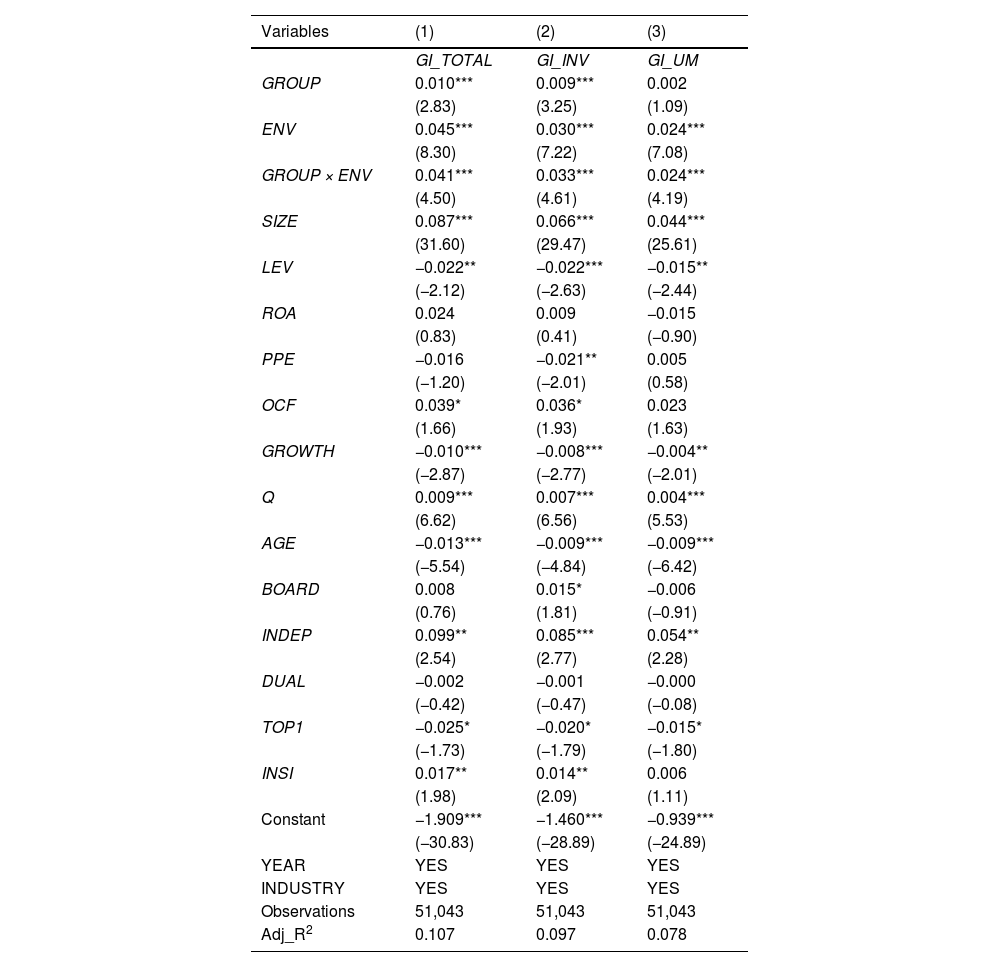

Multiple regression analysisTest of hypothesis H1We adopt model (1) to test the impact of hypothesis H1 in Table 4, which treats the impact of conglomerates on corporate green innovation. In column (1), where the dependent variable is GI_TOTAL, the coefficient of GROUP is 0.021, statistically significant at the 1 % level. In columns (2) and (3), the dependent variables are GI_INV and GI_UM, respectively. The coefficients of GROUP remain significantly positive. This indicates that, relative to independent enterprises, enterprises that are members of a conglomerate exhibit higher levels of green innovation, which supports hypothesis H1a. Our finding provides evidence from an emerging market for research on how organizational forms influence corporate green innovation orientation.

Impact of conglomerates on green innovation.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

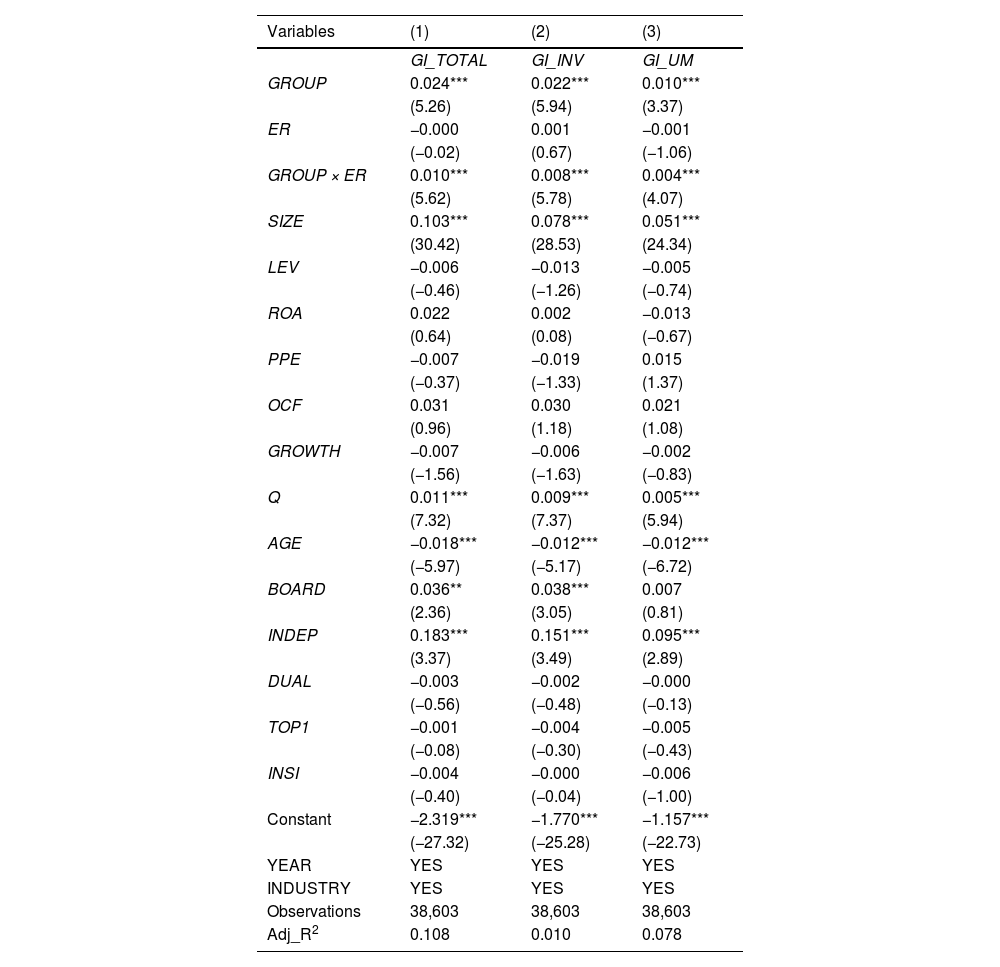

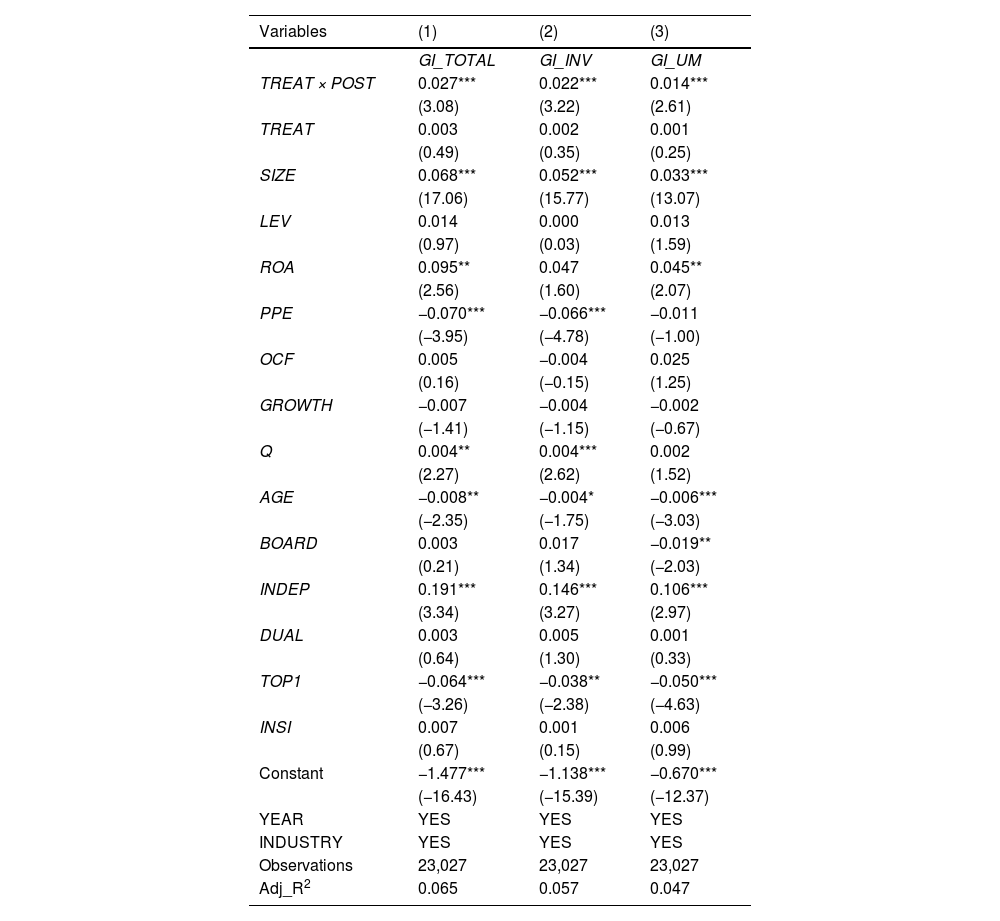

We use model (2) to verify hypothesis H2 in Table 5, which examines the moderating effect of environmental regulation. Regardless of whether the dependent variable is GI_TOTAL, GI_INV, or GI_UM, the coefficient of the interaction term between the business group dummy variable and regional environmental regulation (GROUP × ER) is significantly positive at the 1 % level. The above results indicate that greater regional environmental regulatory pressure promotes the positive effect of business group affiliation on corporate green innovation, thereby supporting Hypothesis H2a. This finding is consistent with the institutional theory and suggests that regulatory authorities should emphasize the role of external environmental regulations to fully leverage the green innovation advantages of business groups.

Environmental regulation, conglomerates and green innovation.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

We use model (3) to test Hypothesis H3, which examines the moderating effect of executives’ environmental awareness; Table 6 presents the results. Regardless of whether the dependent variable is GI_TOTAL, GI_INV, or GI_UM, the coefficient of the interaction term between the business group dummy variable and executives’ environmental awareness (GROUP × ENV) is positive and statistically significant at the 1 % level. This indicates that in enterprises with higher executive environmental awareness, the promotion effect of conglomerates on green innovation is stronger, which supports hypothesis H3a. When executives personally prioritize environmental protection, they are more inclined to proactively leverage the resources and networks provided by the group to promote green innovation. Therefore, environmental awareness can be considered an important criterion in the executive selection process for group-affiliated firms.

Executive environmental awareness, conglomerates and green innovation.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Fig. 3 illustrates the summary results of the research hypothesis tests.

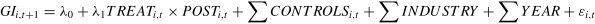

Robustness testsEndogeneity testEnterprises with a higher level of green innovation may attract the entry of other major shareholders, thereby becoming member enterprises of a particular conglomerate. To address the endogeneity challenge induced by reverse causality, we utilize the research scenario of conglomerate status change and adopt a difference-in-differences model (DID).

We consider the scenario of conversion from an independent enterprise to a conglomerate member enterprise. The samples that have transformed from independent enterprises to member enterprises of conglomerates are used as the treatment group, whereas the samples that have remained independent enterprises are used as the control group. The double difference model is as follows:

TREAT is a dummy variable indicating whether the firm belongs to the treatment group, with a value of 1 for the treatment group and 0 otherwise. POST is a variable indicating whether the conglomerate status has changed, with a value of 1 for the year and after the change, and 0 before the change. The coefficients of TREAT × POST reflect the changes in the level of corporate green innovation following the change in conglomerate status. When transitioning from an independent enterprise to a member of a conglomerate, if λ1 is significantly positive, it indicates that the shift from “non-group” to “group” status will enhance corporate green innovation, and vice versa.

Table 7 presents the DID regression results. In columns (1) to (3), the coefficients of TREAT × POST are significantly positive, indicating that green innovation increases significantly after enterprises change from independent enterprises to conglomerate members. This enhances the robustness of our conclusion.

DID.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

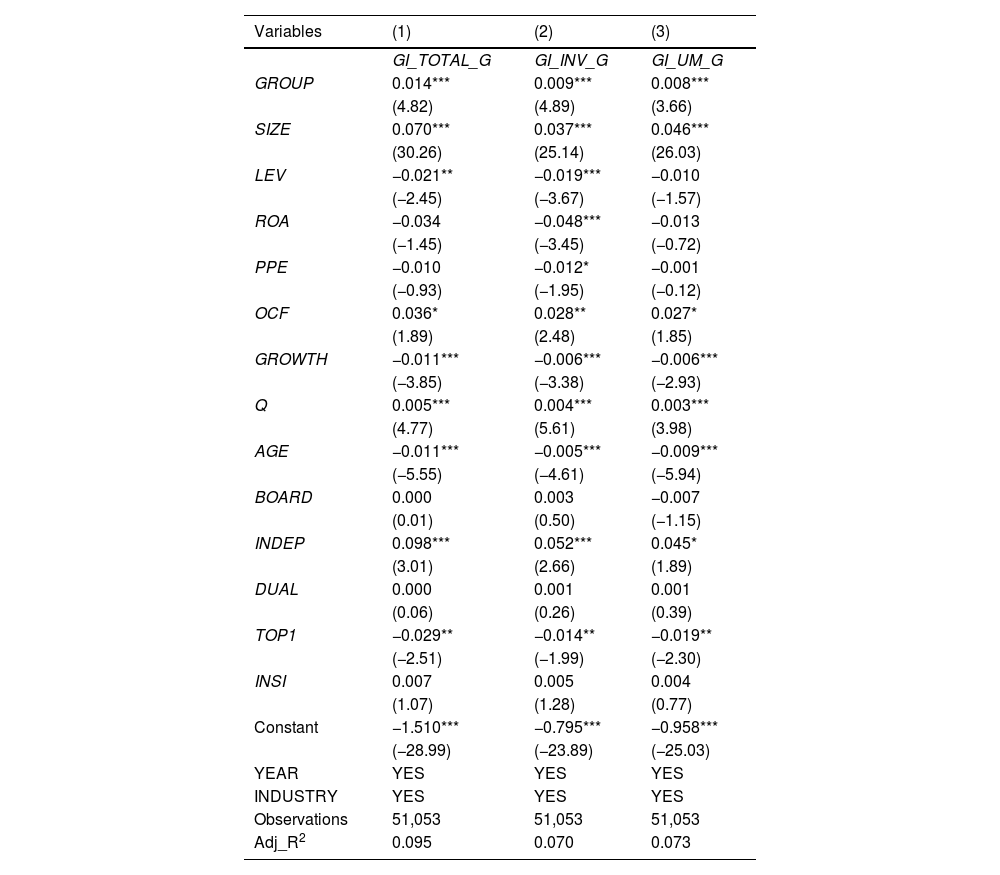

First, we substitute green patent applications with green patent grants (GI_TOTAL_G, GI_INV_G, GI_UM_G) to assess corporate green innovation in Table 8. The coefficient of GROUP is significantly positive, indicating the robustness of our main findings.

Alternative measures for green innovation.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

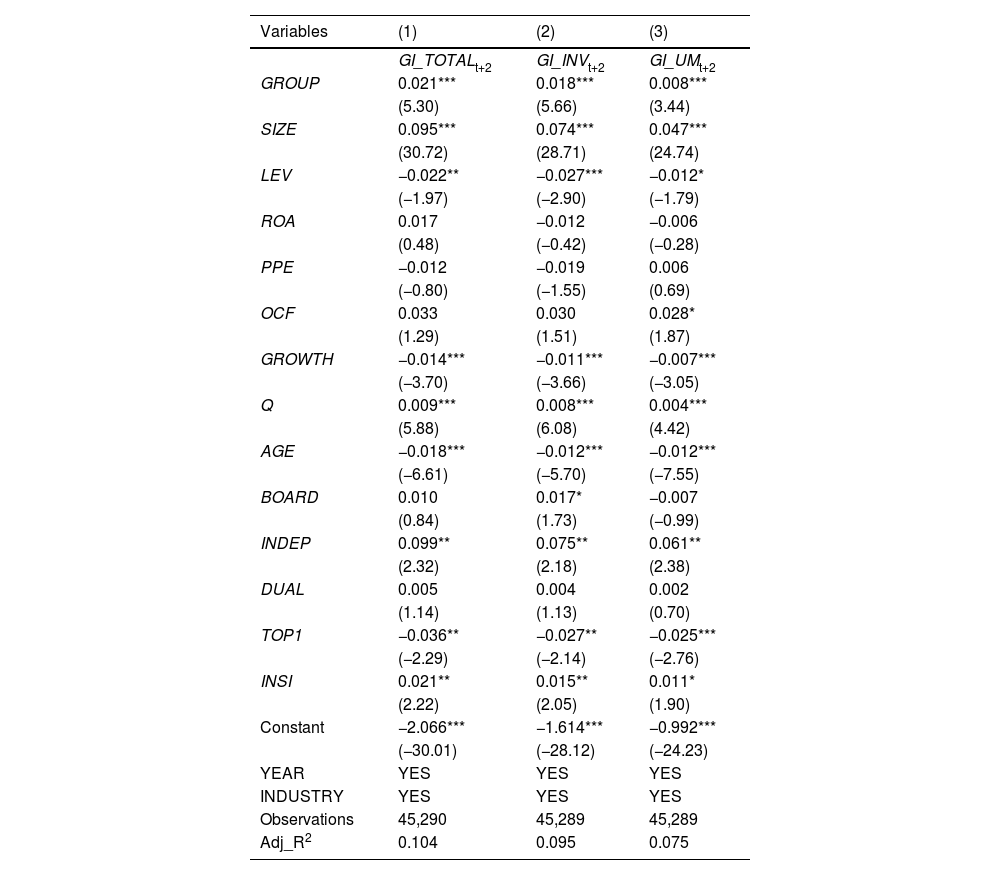

Second, we examine the impact of conglomerates on green innovation over the next two years. Green innovation activities, being a type of innovation, are inherently high-risk and long-term in nature. Therefore, in Table 9, we replace the green innovation level in model (1) from the value in year t + 1 to the value in year t + 2. The coefficient of GROUP is significantly positive, confirming the robustness of our main findings.

Impact on the green innovation in the next two years.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Previous analysis has revealed that conglomerates significantly promote green innovation. Presumably, conglomerates may provide financial support through an internal capital market mechanism and knowledge support through an internal knowledge network, thus improving the green innovation of group member enterprises. Furthermore, we test the above two possible mechanisms.

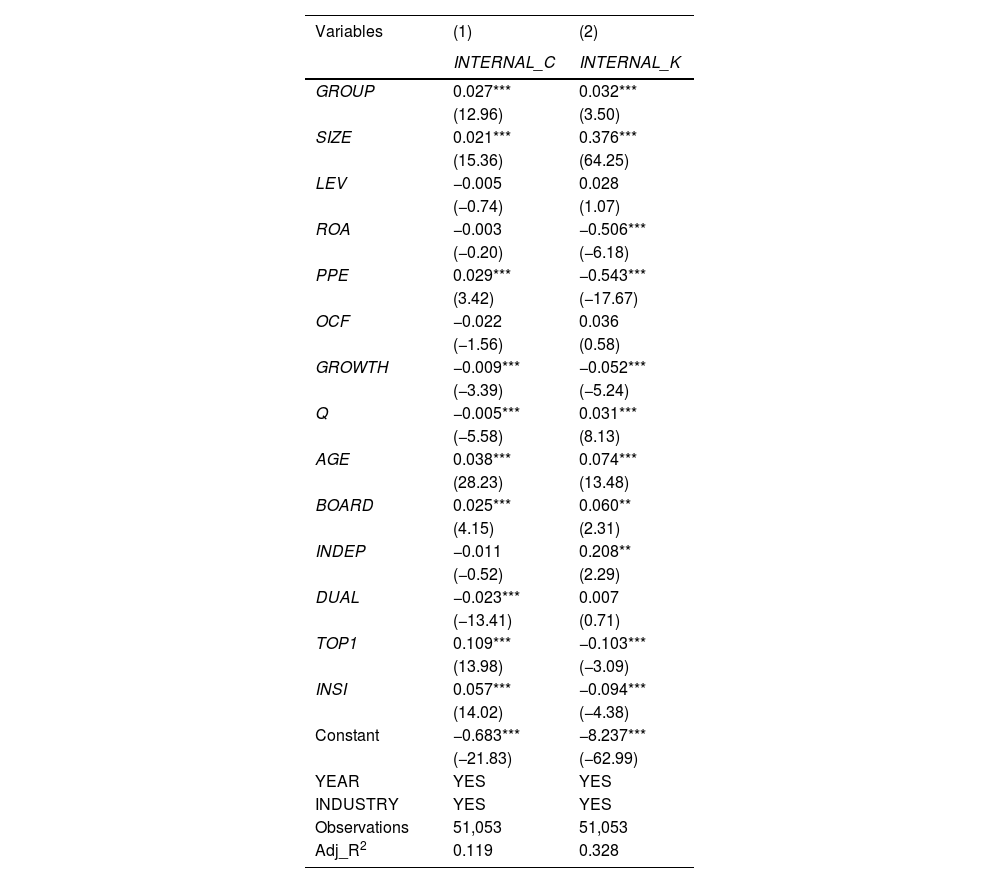

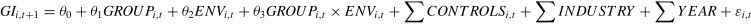

By arranging its subsidiaries to sign Financial Service Agreements with group finance enterprises to build the group’s internal financing market, the conglomerate can allocate funds more effectively. This study considers whether the group finance enterprise has signed the Financial Service Agreement with enterprises to measure whether the conglomerate has constructed the internal financing market for its member enterprises (INTERNAL_C). The dependent variable is INTERNAL_C in Column (1) of Table 10, and the coefficient of GROUP is significantly positive. This indicates that conglomerates can provide financial support to member enterprises by constructing the internal financing market, thus enhancing green innovation.

Mechanism test.

Note: *, **, and *** represent significant at the 10 %, 5 %, and 1 % levels, respectively; t-values based on robust standard errors are in parentheses.

Additionally, the patent citation and cited data between enterprises reflect information sharing and knowledge spillover effects. If an enterprise cites the external patents, the enterprise acquires and absorbs the knowledge of other enterprises (Kim & Steensma, 2017). We measure the internal knowledge network of the conglomerate (INTERNAL_K) by adding 1 to the number of green patents mutually cited within the group and then taking the natural logarithm. A larger value of INTERNAL_K indicates more effective knowledge transfer within the conglomerate. The coefficient of GROUP is significantly positive in column (2) of Table 10, indicating that the conglomerate provides knowledge support to member enterprises to enhance green innovation.

The above tests reveal the dual mechanism through which business groups influence green innovation. On the one hand, via the internal capital market, business groups can provide more stable and lower-cost funding for the green R&D projects of their member firms. On the other hand, through the internal knowledge network, they facilitate the flow and spillover of green technologies and experiences among member firms. Together, these channels secure the necessary resources and capabilities for member firms’ green innovation endeavors.

Conclusions and implicationsResearch conclusionWe explore the impact of conglomerates on green innovation and identify that enterprises within conglomerates exhibit a greater extent of green innovation. This can be attributed to conglomerates easing financing constraints by creating internal capital markets and addressing knowledge gaps through the establishment of internal knowledge networks. The positive effect of conglomerates is more pronounced in regions with stricter environmental regulations and in enterprises led by executives with stronger environmental awareness.

Existing studies have mainly focused on the economic performance of enterprise groups. This pioneering study links enterprise groups with green innovation—a specific environmental governance behavior—and identifies and verifies two key channels through which enterprise groups promote green innovation. This extends the research on the economic consequences of enterprise groups to the field of sustainable development. This research shows that in emerging markets where formal institutions such as financial markets and intellectual property protection may still be imperfect, the internal capital markets and knowledge networks of enterprise groups, as informal institutions, can serve as an effective alternative or complementary mechanism to help member enterprises overcome market failures and engage in green innovation. This expands the application of new institutional economics in the field of environmental governance and provides theoretical insights for understanding the green transformation paths of emerging economies such as China.

Research implicationsThe policy recommendations derived from this study are as follows:

First, regulators should support the development of conglomerates, as this contributes to corporate sustainable transformation. We identified that the organizational structure of conglomerates has a significant positive effect on green innovation. Therefore, regulators should promote policy coordination to support the merger and restructuring of enterprises in line with market-oriented principles. For example, enterprises could be encouraged to pursue asset mergers and acquisitions through external expansion, restructure internally through effective asset reorganization, and foster mergers and alliances between different enterprises.

Second, conglomerates should improve their internal financing markets and internal knowledge networks so that resources can be fully utilized by member enterprises during green transformation. In terms of improving the internal capital market, conglomerates should establish capital pools and set up internal trading platforms to facilitate the coordinated utilization of funds among member enterprises. Regarding the improvement of internal knowledge networks, conglomerates should establish tools and platforms, such as knowledge bases and expert databases, to facilitate the better use of knowledge resources within the organization by member enterprises.

Third, member enterprises should hire executives with strong environmental awareness. This study demonstrates that executives’ environmental awareness has a positive moderating effect on the influence of conglomerates. Therefore, member enterprises committed to green transformation should consider environmental awareness as a key criterion when forming their executive teams.

Limitations and future researchThis study has several limitations, which indicate to avenues for future research.

First, this study mainly examines how conglomerates influence green innovation based on the Chinese context. However, conglomerates in different countries vary greatly in terms of governance structure, culture and resource endowment. For instance, in terms of group governance structure, Chinese business groups are mostly characterized by a pyramid-shaped shareholding structure, while Japanese business groups feature cross-shareholding and a main bank system. This difference in governance structure directly impacts internal resource allocation, decision-making efficiency and risk-taking capacity of the group, which may lead to differences in the impact of enterprise groups on green innovation. From the perspective of the maturity of the capital market, this study identifies that enterprise groups can alleviate financing constraints and promote green innovation through the internal capital market. However, this mechanism may be significantly attenuated in European and American countries with well-developed capital markets. From the perspective of cultural norms, in Chinese collectivist culture, enterprises may be more inclined to respond to the government’s environmental protection policies. However, in the European and American societies dominated by individualism, the environmental protection decisions of enterprises may be more influenced by informal institutional pressures such as individual values and public opinion. This difference may also lead to changes in the impact of enterprise groups on green innovation. In the future, cross-national comparative studies should explore how institutional and cultural factors at the national level interact with the organizational form of enterprise groups to influence green innovation.

Second, this study focuses on the differences in green innovation between group-affiliated enterprises and standalone enterprises, but overlooks the heterogeneity in the governance structure characteristics of business groups themselves. For example, the control mode of business groups over their affiliated enterprises is directly related to the balance between the efficiency of green innovation decision-making and the autonomy of affiliated enterprises. Generally speaking, the operational control mode adopts a high degree of centralization, which is conducive to the unified implementation of green innovation strategies at the group level, but may also restrict the flexibility of affiliated enterprises. The financial control mode, however, overemphasizes the short-term financial returns of affiliated enterprises and may inhibit high-risk, long-cycle green innovation. The strategic control mode, which may possess both strategic orientation and adaptability, is most conducive to promoting green innovation. In the future, multi-case comparative studies should minutely analyze the differences in how business groups influence the green innovation of their affiliated enterprises under different control modes.

Third, while this research primarily analyzes how business groups influence green innovation through internal capital markets and internal knowledge networks, the research perspective can be further enriched by combining the development trends of digital technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence. Digital technologies are reshaping resource allocation and flow within groups, potentially affecting the green innovation behaviors of affiliated firms. Therefore, future studies could, on the one hand, examine whether digital technologies enhance the financing efficiency of internal capital markets for green innovation projects through functions such as precise matching and early risk warning. On the other hand, they could explore how digital technologies break spatiotemporal constraints on knowledge transfer, using tools such as knowledge graphs and intelligent algorithms to accelerate the diffusion and sharing of internal green knowledge, thereby promoting green innovation. Additionally, case studies could be employed to deeply analyze how business groups leverage digital technologies to obtain real-time market and policy information, guiding affiliated firms to promptly adjust their green innovation strategies and enhance their dynamic capabilities for green innovation.

Funding sourcesThis work was supported by the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education (22YJC790026) and Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (2462023YJRC033)

CRediT authorship contribution statementYao Wang: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. Xiaoqing Feng: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. Guangfan Sun: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Supervision. Daosheng Xu: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Investigation.

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

We would like to thank the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of the Ministry of Education (22YJC790026) and Science Foundation of China University of Petroleum, Beijing (2462023YJRC033) for supporting this research.