Technological advancements are forcing firms to innovate quickly to sustain a competitive advantage. However, despite theoretical arguments and empirical findings, the mechanisms that influence the speed of innovation and firms’ international performance are surprisingly unexplored in the international business literature. Therefore, this study offers theoretical rigor through the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities framework to improve our understanding of how firms can achieve international performance. This study develops a conceptual model to investigate the joint effects of international open innovation, international dynamic capabilities, and the speed of innovation on firms’ international performance. This study empirically examines a conceptual model using 303 valid responses from marble manufacturers in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) Pakistan. The results confirm that international open innovation has a positive and significant effect on the international performance of marble manufacturers. The findings also suggest that international open innovation and international dynamic capabilities together influence the speed of innovation and the international performance of marble manufacturers. This study concludes that strong dynamic international capabilities can turn open international innovation into a source of international performance for manufacturers through the speed of innovation. Several theoretical and policy implications are discussed.

Firms operating in dynamic environments are often under pressure to accelerate innovation and gain access to international markets (Fu et al., 2024; Jie et al., 2024; Zahoor et al., 2023; Toroslu et al., 2023). For example, undertaking too many activities within a short time in a dynamic environment may lead to new inefficiencies (Hilmersson et al., 2023, p. 183; Hilmersson et al., 2022). Thus, to manage the complexities of internationalization in dynamic environments and address the challenges posed by time compression diseconomies (TCD), a well-defined strategic approach is required (Srikanth et al., 2021; Cool et al., 2016). TCD refers to the situation in which rapid innovation results in diminishing returns, inefficiency, and compromised performance. Research indicates that firms exporting from emerging economies are particularly affected by TCD as they face resource constraints, regulatory complexities, and challenges in market adaptation, among other issues (Hilmersson et al., 2023, p. 183; Hilmersson et al., 2022). Do et al. (2023) argue that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) often rely on their social networks to achieve international performance with limited resources in dynamic environments. They further asserted that social networks and openness to innovation are critical for acquiring new market knowledge. Freixanet (2014) acknowledges that the internationalization process is not static but dynamic, and over time, SMEs must redefine their reasons for operating in international markets. We argue that firms operating in international markets face uncertainties that require distinct innovation strategies. One such strategy is open innovation, which has been studied extensively in domestic settings. Open innovation involves engaging key stakeholders to facilitate the flow of knowledge from diverse sources (Chabbouh & Boujelbene, 2023). Firms achieve open innovation through two main approaches: outside-in and inside-out. Lipp et al. (2022) found that organizations embracing open innovation experienced 59 % higher revenue growth than those that did not. While domestic openness to innovation may not necessarily accelerate innovation, openness to international innovation via global knowledge networks, collaborations, and technological exchanges can enhance organizational agility, mitigate the negative effects of TCD, and foster more effective innovation cycles. Thus, openness to international innovation may be a win-win strategy for improving international business performance. However, the role of openness to international innovation in influencing innovation speed and international business performance remains underexplored, particularly for firms in emerging economies (Zahoor et al., 2022). This gap highlights a critical area that may offer valuable insights into how firms can optimize their innovation strategies in resource-constrained and dynamic environments.

This gap is both significant and timely in light of recent calls for further investigation. For instance, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between open innovation and firms’ international performance in dynamic environments, Du et al. (2023, p. 1238) recommend that future research consider the temporal aspect of innovation. Similarly, Van-Criekingenv (2020, p. 710) argues that an analysis of time-based innovation could yield significant insights, as little attention has been paid to this topic in the existing literature. Additionally, understanding time compression problems in internationalization is crucial because a close relationship exists between innovation speed and international business performance (Hilmerson et al., 2023; Du et al., 2023; Do et al., 2023). Despite these calls, there is a lack of comprehensive studies that explicitly address whether openness to international innovation can truly accelerate innovation and ultimately enhance international performance. Thus, to address these shortcomings, we argue that the relationship between openness to international innovation, speed of innovation, and international business performance in dynamic business environments is complex but can be understood through the lens of the resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capabilities framework (Teece, 2020; Chesbrough, 2017; Barney, 1991). We propose that a firm's dynamic capabilities consolidate internal and external knowledge and reconfigure processes and routines, which not only affect its international performance but also enable continuous innovation. Thus, international dynamic capabilities and the pace of innovation may moderate the relationship between international open innovation and international performance. Specifically, a firm's international sensing capability identifies internationalization gaps, and knowledge of these gaps is collected through international inbound open innovation. Firms with international reconfiguration capabilities recombine their internal and external knowledge, enabling them to innovate more rapidly. As a result, international open innovation and dynamic international capabilities may predict international performance together.

This study contributes to the international business literature in several ways. First, it highlights the unexplored relationship between innovation speed and international business performance in a dynamic environment. Second, it addresses the previously neglected joint effects of international open innovation, the pace of innovation, and international performance. Third, it provides a more comprehensive understanding of causal mechanisms through the RBV and dynamic capabilities perspectives, which, according to Chabbouh and Boujelbene (2023, p. 11), require further exploration. Fourth, this study merges the RBV and dynamic capabilities framework, thereby expanding the scope of both theories within international business literature.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2.1 provides the theoretical background underpinning the current study, followed by a review of the literature on the hypothesized relationships, including the conceptual framework. Section 3 explains the research design followed by a detailed presentation of the data analysis and results. The paper concludes with a discussion of the implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

Literature reviewTheoretical backgroundDrawing on dynamic capabilities theory and the RBV (Teece, 2020; Barney, 1991), this study suggests that international open innovation enables firms to access external resources and develop new capabilities essential for achieving international performance. From the RBV, international open innovation enhances a firm's resource base by enabling the acquisition of implicit and explicit knowledge from diverse sources (Chesbrough, 2017, 2003). However, acquiring new resources from external sources can slow the innovation process if dynamic capabilities are not in place (Teece, 2020). Firms with strong dynamic capabilities can sense external opportunities, seize them to accelerate innovation, and reorganize their organizational resources in response to market changes (Yamin & Kurt, 2018; Pinho et al., 2016; Ciravegna, 2011). Taken together, these arguments suggest that firms practicing international open innovation not only expand their resource base, but also develop the agility required to innovate rapidly and sustain strong performance in international markets (see Fig. 1). To summarize, the configuration of organizational resource availability, pace of innovation, and market responsiveness provide a comprehensive explanation of how open innovation drives international performance.

International open innovation and international performanceDo et al. (2023) explore the relationship between innovation and international performance in Vietnamese SMEs and find that innovation is a crucial determinant of internationalization. However, the literature on whether innovation leads to internationalization leads to innovation is inconsistent and controversial (Du et al., 2023, p. 1216; Shin et al., 2022; Freixanet, 2014; Zhou et al., 2007). Aw et al. (2009) identify the relationship between internationalization and innovation in Taiwan. On the other hand, scholars such as Pittiglio et al. (2009), Kiriyama (2012), and Aw et al. (2001) advocate a learning-by-exporting view. Authors who favor internationalization and innovation (e.g., Ding et al., 2021; Pattnaik et al., 2021; Chan & Pattnaik, 2021; Nuruzzaman et al., 2019; Lynch & Jin, 2016; Lamotte & Colovovic, 2010; Rios-Morales & Brennan, 2009; Becker & Egger, 2013; and Kafouros et al., 2008) argue that internationalization creates opportunities for newness. They further contend that contextual differences across countries may compel firms to innovate. Conversely, scholars who support the positive relationship between innovation and internationalization argue that “product innovation is a key factor for successful market entry,” “SMEs engaged in product or process innovation are more likely to internationalize,” “innovation and internationalization are complementary strategies for small businesses,” and “innovation is a critical factor for internationalization,” and “internationalization is the result of product innovation.” Comparatively, the relationship between innovation and international performance is unanimous in the literature (Orero-Blat et al., 2021; Freixanet, 2014, p. 62). According to Zahoor et al. (2022), organizations operating in international markets demand open innovation; however, their impact on international business performance remains unexplored.

Therefore, to paint a more comprehensive picture of the factor(s) leading to firms’ international performance, we theorize that international open innovation is an effective strategy for improving international performance because firms that collaborate with key stakeholders may reduce trepidation related to international expansion. Open innovation itself is not innovation but an innovation management strategy that accelerates internal innovation processes by acquiring knowledge from diverse sources and expanding the market for external use of innovation (Chesbrough et al., 2014; Chesbrough, 2003). Open innovation takes two forms: outside-in and inside-out (Audretsch & Belitski, 2023). Outside open innovation, firms acquire knowledge by creating networks with external parties to develop new products, processes, or technologies. In inside-out open innovation, firms transfer knowledge to support external entities. Thus, open innovation is a sustainable model of innovation because the relevant knowledge can be sourced from anywhere in the world and applied to any geographical context (Moreno-Menéndez & Casillas, 2014, p. 86). Bernal et al. (2022), Edeh et al. (2020), and Gaur et al. (2019) find that collaboration with external stakeholders positively influences export performance. Similarly, Pinho and Prange (2016) report that social networks positively and significantly affect the international performance of Portuguese SMEs. Conroy et al. (2023) conclude that sourcing knowledge from external sources and transferring it across multinational enterprise (MNE) networks enhances innovative capacity. Do et al. (2023, p. 17) identify a positive and significant relationship between innovation and internationalization in the presence of inter-organizational social networks. Based on these findings, we hypothesized that:

H1: There is a positive and significant relationship between international open innovation and international performance.

Open innovation, pace of innovation, and international performanceThe literature on openness to innovation and time-based innovation in the context of internationalization is limited and inconsistent (Du et al., 2023, p. 1216). For example, Salge et al. (2013) found that search openness is positively and significantly related to the success of new product development. However, they argue that this relationship is more effective at the ideation stage for explorative projects. Measuring the direct link between engaging in research and development (R&D) collaborations and the completion of product development, as well as joining industry associations and the completion of product development, Toroslu et al. (2023, p. 8) found that engaging in R&D has a slowdown effect on product development. In contrast, joining industry associations has a positive impact on the speed of product development. Owing to the operationalization of the construct “speed of innovation” (i.e., product development vs. product launching) and its measurement in different units of analysis, the literature to date remains inconclusive (Milan et al., 2020, p. 5). However, a descriptive report from the Capgemini Research Institute (2023) stated that 55 % (550 executives) confirmed that open innovation increased organizations' speed of innovation. Firms collaborating with key stakeholders to develop new products or services gain lead time advantages (Van Criekingen, 2020, p. 711), which affect internationalization (Donbesuur et al., 2020; Pinho & Prange, 2016). The acquisition of new knowledge not only supports innovation and internationalization but also enables firms to innovate continuously (Do et al., 2023, p. 17). Firms strive to acquire and integrate new knowledge (Cassiman & Veugelers, 2006) to innovate quickly and regularly. Innovation is defined as a firm's ability to launch new products or services before competitors or soon thereafter (Mareno-Moya & Munuera-Aleman, 2016; Cankurtaran et al., 2013; Allocca & Kessler, 2006). Innovation speed allows firms to gain a first-mover advantage.

Several antecedents of innovation speed have been identified in the literature, for example, faculty-inventors’ participation (McCarthy & Ruckman, 2017), formalization (Chen, Damanpour & Reilly, 2010), knowledge sourcing (Van Criekingen, 2020), top management support, goal clarity, and team leadership (Chen et al., 2010, p. 19), among others. According to Toroslu et al. (2023), firms that develop their innovations in collaboration with external parties benefit from better appropriation through lead time advantages. Understanding the speed of innovation in this era of technological advancement is critical because technological progress has shortened product lifecycles, forcing firms to innovate more rapidly. The ability to innovate quickly has become a key success factor (Do et al., 2023; Toroslu et al., 2023). Innovation speed is a significant source of competitive advantage. For example, whether as first movers or fast followers, firms acquire new competencies that differentiate them from key players in the market, leading to a competitive advantage. Innovation speed can translate into firm profitability through timely product entry, response to market demand, and satisfying impatient customer wants (Chen et al., 2010, p. 8). In the context of international business, Hilmersson et al. (2023, p. 196) find that a high speed of internationalization is the result of rapid innovation. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2: International openness to innovation is positively and significantly related to international performance via speed of innovation.

Moderated-mediation of international dynamic capabilities and speed of innovationIn practice, the relationship between open innovation and a firm's international performance is complex, and empirical research on moderated-mediating mechanisms remains scarce. For this reason, Do et al. (2023, p. 4), Zhang and Liu (2023), and Ding et al. (2021) emphasize the need for further research on how and when social networks influence firms’ international performance. For example, open innovation is a necessary but insufficient condition for firms’ international performance because the rapid pace of technological advancement has shortened product life cycles, thereby forcing firms to innovate quickly. Thus, addressing time compression problems in internationalization is critical, as there is a close relationship between the speed of innovation and a firm's international performance (Do et al., 2023; Du et al., 2023). Hilmersson et al. (2023) argue that faster internationalization is the result of a fast pace of innovation. Conversely, Toroslu et al. (2023) pointed out that engaging in R&D can slow the speed of innovation for new ventures. However, Hamersson et al. (2023, p. 195) found that “newness is not a liability, but the advantage that drives and accelerates internationalization.” Toroslu et al.'s (2023) explanation overlooks the fact that acquiring new knowledge from external sources could potentially slow the innovation process when dynamic capabilities are not in place (Milan et al., 2020; Elango & Pattnaik, 2007). This viewpoint aligns with Chesbrough's (2017) findings, which suggest that companies must invest adequately in building dynamic capabilities among employees to generate new products, processes, and technologies as early as possible. According to Teece (2020, p. 156), “dynamic capabilities are a firm's ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure its internal and external competences in response to environmental uncertainty.” Recent findings suggest that firms employing an open innovation strategy for knowledge acquisition must develop dynamic capabilities (Meuric, 2025; Teece, 2020; Zhou et al., 2019; Xin et al., 2018; Wang & Wang, 2012). Thus, international open innovation and dynamic international capabilities together influence the speed of innovation and firms’ international performance.

For instance, knowledge that falls beyond a firm's access may be overlooked because the firm cannot easily comprehend it (Zhou et al., 2019, p. 733–735). However, a firm with openness to innovation and strong international dynamic capabilities, such as international sensing, international integration, and international reconfiguration capabilities, can better understand international markets, which may lead to constant innovation (Brock & Hitt, 2024; Sadeghi et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2016). We argue that strong international dynamic capabilities can transform international open innovation into a source of internationalization through innovation speed. Thus, firms must develop dynamic international capabilities to fully benefit from open international innovation. Sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring at the international level enables firms to respond to diverse environmental opportunities, thereby accelerating innovation. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

H3: The relationship between international open innovation and international performance is moderated and mediated by firm international dynamic capabilities and the firm's speed of innovation.

MethodologySampling design and data collectionThe current study was conducted on the relatively less understood marble manufacturing SMEs in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), Pakistan. This sample offers several advantages. Pakistan is the 6th largest marble extractor in the world and has significant reserves of high-quality marble. Despite this, the overall performance of the sector has not fully realized its export potential (Ahmad et al., 2022; Saadat, 2016). Pakistan is estimated to have 300 billion tons of marble and onyx reserves, 78 % of which are located in the KP province, with 601 manufacturers. The province provides diverse types of marble at competitive prices, with growing demand in international markets. The sector demonstrates high potential for growth, as marble is of export quality (Nehal, 2024). However, no significant recent improvements have been made in this sector (SMEDA, 2020).

For this study, the measurement items were adapted from existing literature. Whenever possible, modifications were made to align the scales with the marble manufacturing context. The survey questionnaire explicitly included selection criteria, whereby marble manufacturers were asked to provide primary data regarding their engagement in internationalization activities, innovation activities, and international networks. Only the marble manufacturers that met the specified criteria were included in this study. Consequently, 370 of 601 units qualified, ensuring the robustness and relevance of the sample. The respondents included business and export managers. Data were collected via a self-administered questionnaire from marble manufacturers at a single time. A total of 303 valid responses were analyzed using SmartPLS version 4.0.1.1. This study follows SMEDA's definition of an SMEs (fewer than 250 employees and annual sales of 250 million PKR). To address potential single-rater bias, Harman's single-factor test for common method bias (CMB) was conducted. The results showed that a single factor explained 23 % of the variance, indicating that the data did not suffer from CMB.

Measurement instrumentsThe international performance of marble manufacturing SMEs was measured using the scale developed by Donbesuur et al. (2020, p. 6). The owners/managers of marble manufacturers were asked to rate their international performance on a five-point Likert scale (anchored by 1 = much lower to 5 = much higher) compared to similar manufacturers that had internationalized. The items included: “international sales growth,” “return on investment from international business,” “market share in international markets,” “international profitability,” and “overall international performance.” The international open innovation construct was measured using a scale adapted from Zahoor et al. (2022, p. 765) with the necessary rewording to suit the study context. Owners and managers were asked to indicate to what extent their firm: “builds relationships with new international alliance partners (suppliers, marble manufacturers, customers, consultants) for inbound open innovation;” “builds relationships with new international alliance partners (suppliers, marble manufacturers, customers, consultants) for outbound open innovation;” “purchases intellectual property from international alliance partners;” “sells novel information and knowledge to international alliance partners;” and “offers royalty agreements to other international alliance partners to better benefit from our innovation efforts.” The measures of international dynamic capabilities were adapted from Xin et al. (2018, p. 85) and Pinho and Prange (2016, p. 7). Respondents were asked to rate their perception on a five-point scale regarding how quickly: “the unit identifies changes in technology and the market environment;” “the unit enhances understanding of overseas customer requirements;” “the unit acquires export market related information about new products;” “the firm integrates international market and customer knowledge with knowledge of emerging technologies;” and “the firm quickly updates and adjusts existing organizational knowledge to meet the demands of international customers.” The speed of innovation was measured using a five-point scale adapted from Wang et al. (2016) and Wang and Wang (2012) with necessary changes to align with the study context. Respondents were asked to indicate agreement or disagreement with the following statements: “The manufacturing unit comes up with novel ideas faster than key competitors,” “The unit launches new products faster than key competitors,” “The unit develops new products faster than key competitors,” “The unit implements new processes faster than key competitors,” and “The marble manufacturing unit solves problems faster than key competitors.” For further details, see Table 1.

Reliability and validity of constructs.

| Item description | Loading |

|---|---|

| International open Innovation adapted fromZahoor et al. (2022, p. 765)(a=0.870; CR = 0.908; AVE = 0.664) | |

| “Our manufacturing unit builds relationships with new international alliance partners (suppliers, marble manufacturers, customers, consultants) for inbound open innovation” | 0.828 |

| “Our manufacturing unit builds relationships with new international alliance partners (suppliers, marble manufacturers, customers, consultants) outbound open innovation” | 0.621 |

| “When required, our manufacturing unit purchases intellectual property from international alliance partners” | 0.749 |

| “Our manufacturing unit sells novel information and knowledge with international alliance partners” | 0.920 |

| “Our manufacturing unit offers royalty agreements to other international alliance partners to better benefit from our innovation efforts” | 0.918 |

| Speed of Innovation adapted fromWang et al. (2016)andWang and Wang (2012)(a=0.858; CR = 0.900; AVE = 0.651) | |

| “Our manufacturing unit comes up with novel ideas faster than key competitors” | 0.641 |

| “Our manufacturing unit launches new products faster than key competitors” | 0.923 |

| “Our manufacturing unit develops new products faster than key competitors” | 0.628 |

| “Our manufacturing unit implements new processes faster than key competitors” | 0.893 |

| “Our manufacturing unit is faster to solve problems than key competitors” | 0.893 |

| International dynamic capabilities adapted fromXin et al. (2018, p. 85)andPinho and Prange (2016, p. 7)(a=0.918; CR = 0.936; AVE = 0.762) | |

| “Our manufacturing unit can quickly identify the changes in technology and the market environment” | 0.960 |

| “Our manufacturing unit enhances understanding of overseas customer requirements” | 0.890 |

| “Our manufacturing unit acquires export market related information about new product” | 0.687 |

| “Our manufacturing unit can integrate international market and customer knowledge together with knowledge of emerging technologies” | 0.834 |

| “Our manufacturing unit can quickly update and adjust existing organization knowledge to meet demand of international customers” | 0.964 |

| International performance adapted fromDonbesuur et al. (2020, p. 6)(a=0.952; CR = 0.953; AVE = 0.840) | |

| International sales growth | 0.905 |

| Return on investment from international business | 0.888 |

| Market share in international markets | 0.929 |

| International profitability | 0.928 |

| Overall, international performance | 0.934 |

Source: compiled by the authors.

The reliability of the constructs was assessed by measuring Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR) values, and construct validity was established by assessing convergent validity using the average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 1, the Cronbach's alpha values ranged from 0.858 to 0.952 and the CR values ranged from 0.900 to 0.953, both exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. This confirmed the reliability of the measurement instrument. Additionally, convergent validity was assessed to establish the construct validity of all the measures. The standardized factor loadings converged on their relevant constructs, which was further confirmed using Fornell and Larcker's (1981) AVE. As Table 1 shows, all the AVE values were above the recommended threshold of 0.50, ranging from 0.651 to 0.840.

Table 2 reports the direct and indirect results of the hypothesized structural relationships between international dynamic capabilities, international open innovation, speed of innovation, and international performance. This study argues that a close relationship exists between international open innovation and international performance (H1). The findings support this hypothesis, showing that international open innovation, or collaboration with external stakeholders, positively and significantly affects international performance (β = 0.476, t > 1.96, p < 0.05, with a lower limit of 0.412 and an upper limit of 0.540).

Path Coefficients, t-values, and p-values.

Source: author's calculations.

The relationship between international open innovation and speed of innovation, as well as the relationship between speed of innovation and international performance, is also significant. The moderating role of international dynamic capabilities in the relationship between international open innovation and speed of innovation is positive and significant at the 5 % level (t = 4.42, p < 0.05). This finding indicates that acquiring international knowledge accelerates the innovation process in the presence of dynamic international capabilities (see Table 2).

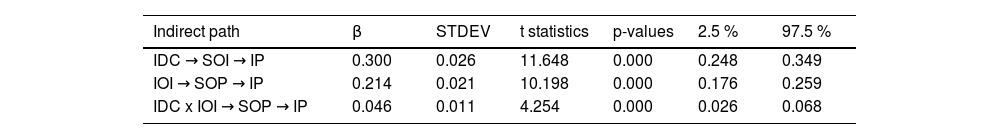

Regarding H2, this study argues that the relationship between international open innovation and the international performance of marble manufacturers is indirect, with innovation speed acting as the mediating mechanism. As shown in Table 3, the findings support H2, indicating that speed of innovation is the underlying mechanism linking international open innovation and international performance (β = 0.214, t > 1.96, p < 0.05, with lower and upper limits of 0.176 and 0.259, respectively).

For H3, we argue that strong international dynamic capabilities can transform open innovation into international performance through the speed of innovation. The study findings fully support H3 (β = 0.046, t > 1.96, p < 0.05, with a lower limit of 0.026 and an upper limit of 0.068). These results suggest that marble manufacturers with both international open innovation and dynamic international capabilities comprehend international markets better, which positively influences continuous innovation. Thus, the combination of international open innovation and international dynamic capabilities significantly impacts the speed of innovation, and consequently, international performance (see Fig. 2).

Discussion and conclusionThis study aimed to address two critical issues in the innovation management and international business literature. Some scholars posit that the relationship between innovation and international performance is causal, while others argue that reciprocal causation exists between innovation and internationalization. We agree with the latter perspective, arguing that internationalization offers opportunities for newness. However, engaging in too many activities in new markets with limited resources can lead to inefficiency. To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the former relationship, this study theorizes that international open innovation could be an effective, yet insufficient, strategy for improving the performance of marble manufacturers. This insufficiency arises because the rapid rate of technological advancement has shortened product lifecycles, forcing firms to innovate quickly. To explore this phenomenon, we introduce international dynamic capabilities and speed of innovation into the relationship between international open innovation and the international performance of marble manufacturers. We argue that strong international dynamic capabilities in marble manufacturers can transform open innovation into a source of international performance through the speed of innovation.

The results confirmed that international open innovation has a positive and significant relationship with the international performance of marble manufacturing businesses (β = 0.476, t > 1.96, and p < 0.05, with a lower limit of 0.412 and an upper limit of 0.540). This finding is consistent with that of Zahoor et al. (2022, p. 774), who demonstrate that international open innovation enables firms to integrate international market and customer knowledge with knowledge of emerging technologies, thereby updating existing organizational knowledge to meet the demands of international customers and ultimately enhancing international business performance. This finding also aligns with the theoretical perspectives of RBV and social networks (Do et al., 2023; Yamin & Kurt, 2018; Chesbrough, 2017; Pinho et al., 2016; Chesbrough, 2003; Barney, 1991), suggesting that integrating international knowledge supports firms’ international performance.

The study results further confirm that speed of innovation mediates the relationship between international open innovation and international performance for marble manufacturers (β = 0.214, t > 1.96, and p < 0.05, with a lower limit of 0.176 and an upper limit of 0.259). This finding aligns with that of Van Criekingen (2020, p. 719), who states that external knowledge sourcing acts as a catalyst for innovative performance through a lead time advantage. The result also aligns with Milan et al. (2020, p. 23) and Romero‐Martínez et al. (2017), who find that inbound international open innovation activities support firms in acquiring new knowledge that is essential for constant innovation and improved organizational performance. This result helps reconcile the association between innovation and international performance, contributing to the existing literature by clarifying how innovation leads to international performance.

Furthermore, insights from previous research also provide potential explanations for our findings, particularly that international open innovation is necessary but insufficient for the pace of innovation and international performance in a dynamic business environment (Teece, 2020). To address this gap, we argue that the acquisition of external knowledge, as suggested by Chesbrough (2017), could potentially slow the innovation process if a company lacks strong international dynamic capabilities to process the influx. To test this, we examined the third hypothesis: international dynamic capabilities moderate the mediated relationship between international open innovation and international performance via the speed of innovation. The findings support this hypothesis (β = 0.046, t > 1.96, and p < 0.05, with a lower and upper limit of 0.026 and 0.068, respectively). These results suggest that international open innovation and dynamic international capabilities together influence the speed of innovation and the international performance of marble manufacturers. The buffering effect of international dynamic capabilities reduces the negative impact of environmental uncertainty, transforming international open innovation into improved international performance through innovation speed. This finding is consistent with Teece (2020), who suggests that firms that implement open innovation strategies for knowledge acquisition require dynamic capabilities. Thus, firms must possess strong international dynamic capabilities to fully benefit from open innovation. This result is also in line with Brock and Hitt's (2024) study, which finds that firms with international dynamic capabilities and international open innovation are better positioned to understand international markets, enabling continuous innovation and enhancing international performance. In summary, this study finds that strong international dynamic capabilities can transform open innovation into a source of international performance for marble manufacturers through the speed of innovation.

Theoretical implicationsThis study provides a novel perspective on a potential relationship that has been overlooked thus far, namely the impact of international open innovation on the international performance of marble manufacturers. These findings contribute to the understanding of the relationship between innovation and international performance by elucidating how international open innovation influences international performance. In addition, this study sheds light on the mechanisms underlying this relationship, particularly in the context of marble manufacturing. Furthermore, this study integrates two prominent frameworks–the RBV and dynamic capabilities–into a single cohesive structure, thereby expanding their scope within international business literature. We argue that open international innovation and dynamic international capabilities play complementary roles in accelerating innovation and enhancing access to international markets. By doing so, this study not only advances the theoretical discourse but also contributes to the emerging and understudied marble manufacturing sector. Despite its potential for significant growth, this sector has seen only a few recent improvements (SMEDA, 2020).

Practical implicationsThese results highlight the fact that international open innovation is crucial to the international performance of marble manufacturers. Therefore, marble manufacturers should focus on forming formal strategic alliances with international partners. This study encourages these units to consider both international dynamic capabilities and international open innovation as means of improving their innovation speed. This is because strong dynamic international capabilities can transform open innovation into a driver of innovation speed. To accelerate both innovation and internationalization, our findings suggest that marble manufacturers should concurrently manage international open innovation and dynamic capabilities. We recommend that marble manufacturing unit managers invest in developing dynamic international capabilities to effectively collaborate with external stakeholders. This approach enables them to align their internal capabilities with external knowledge flow. By doing so, managers can optimize resource allocation, foster a culture of continuous improvement, and enhance flexibility in response to environmental dynamics.

Additionally, our findings provide strategic insights for decision-makers and policymakers to unlock the full export potential of Pakistani marble. They should prioritize investments in innovation infrastructure and human capital development to enhance the speed of innovation and the international performance of marble manufacturers. Firms that leverage international networks to acquire new knowledge develop capabilities that contribute to a sustainable competitive advantage. This study also offers a comprehensive guide for entrepreneurs and managers on accelerating innovation in marble manufacturers operating in dynamic environments, thereby improving international performance.

Limitations and future research directionsSimilar to other studies, this study has some limitations; therefore, the findings should be interpreted with caution. The generalizability of the findings is limited because the sampling was restricted to marble manufacturers in KP, Pakistan. Future research could test the conceptual framework developed in this study across dynamic industries and regions. While this study contributes to the understanding of the relationship between innovation and internationalization from the perspectives of open innovation and the pace of innovation, further exploration of the complex interaction between internationalization and innovation is required. Moreover, this study focuses on traditional manufacturers. Building on the current research, future studies could examine these relationships in the digital and high-tech sectors. The data for this study were collected at a single point in time, which limited the ability to capture changes over time. Future research could adopt longitudinal designs to track data across different periods. Another interesting avenue for future research is to explore the three-way interaction between firm age and intangible resources on the relationship between international open innovation and the speed of innovation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementNoor Ul Hadi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Imtiaz Ali: Investigation, Data curation.