This study examines how psychological mechanisms shape entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities. Specifically, it investigates the relationships among self-stigma, resilience, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial motivation, and how these factors interact under conditions of systemic exclusion. Drawing on survey data, this study employs binary structural equation modeling using Mplus. The results reveal that entrepreneurial self-efficacy negatively affects entrepreneurial motivation in this context, contrary to dominant theoretical assumptions. Notably, entrepreneurial self-efficacy has no significant effect on entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities, while entrepreneurial motivation serves as a key driver. Resilience, while undermining self-efficacy, significantly enhances motivation, and self-stigma exerts an indirect positive influence on entrepreneurial motivation. These findings indicate that the psychological mechanisms assumed to be universal in mainstream entrepreneurship theories might not apply in the same way to individuals with disabilities. Under conditions of structural inequality and social exclusion, psychological traits operate differently—and sometimes paradoxically—shaping entrepreneurial behavior in ways that diverge from conventional models. The findings suggest that disability entrepreneurship is not merely an extension of existing theories but a distinct domain requiring alternative analytical frameworks and theoretical reorientation.

Entrepreneurship provides individuals with a powerful pathway to economic empowerment and personal fulfillment. This holds particular significance for individuals with disabilities, for whom entrepreneurship can serve as a critical means of achieving financial independence and self-determination (Norstedt & Germundsson, 2023). With limited opportunities in traditional employment, stemming from systemic discrimination and structural accessibility barriers, entrepreneurship is a viable alternative for fostering self-sufficiency and facilitating economic inclusion (Ashalatha et al., 2024). Understanding and supporting the unique experiences of entrepreneurs with disabilities has become an increasingly important topic in entrepreneurship research (Hidegh et al., 2023). Promoting entrepreneurial engagement among individuals with disabilities is not only essential for their personal advancement but also contributes to the broader socio-economic development of more inclusive and equitable societies (Vargas-Zeledon & Lee, 2024). Although inclusive entrepreneurship research has made progress with groups such as women and racial minorities, notable differences remain in entrepreneurial mechanisms across disadvantaged groups (Bruton et al., 2021; Hidegh et al., 2023). For instance, although gender and racial discrimination negatively impact entrepreneurship, individuals with disabilities differ from other disadvantaged groups in the traditional labor market. They often face significant barriers to stable employment owing to physical or psychological constraints, making necessity-driven entrepreneurship a common alternative (Lim et al., 2024). There is limited research on how entrepreneurs with disabilities overcome obstacles arising from psychological and external challenges. A deeper exploration of their entrepreneurial journeys would offer systematic insights into the barriers and opportunities they face while contributing to social and economic inclusion.

Recent research increasingly highlights that the physical, psychological, and social characteristics of individuals with disabilities can serve as vital resources for facilitating entrepreneurial engagement and success (Ashalatha et al., 2024; Hsieh et al., 2019; Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017). Many individuals with disabilities demonstrate traits such as high risk tolerance, perseverance, and ambition (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017), along with a strong motivation for self-actualization and personal growth (Nikolaev et al., 2020). In some cases, disabilities may enhance creativity, adaptability, and other socio-technical skills that are particularly valuable in entrepreneurial contexts. Notably, studies have identified a positive association between certain mental health conditions, such as ADHD, and entrepreneurial tendencies (Greidanus & Liao, 2021). However, traditional entrepreneurship theories often overlook these unique challenges and additional constraints. Research explicitly addressing the distinct psychological and societal barriers faced by entrepreneurs with disabilities, such as self-stigma and limited access to social capital, remains scarce (Bakker & McMullen, 2023). Moreover, much of the existing literature tends to focus narrowly on entrepreneurial intentions rather than actual entrepreneurial behaviors, and frequently examines psychological and structural barriers in isolation rather than as interconnected and mutually reinforcing factors.

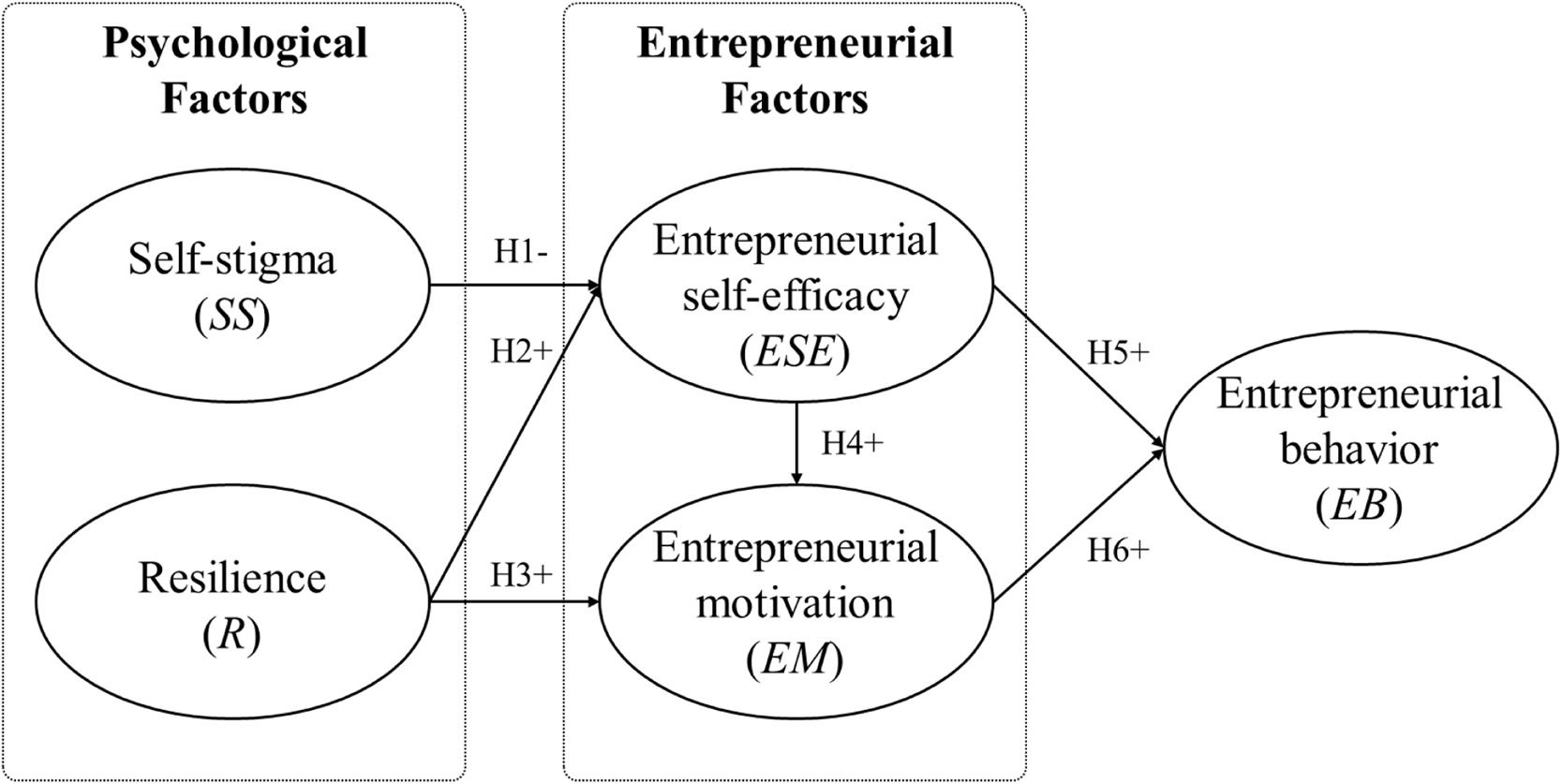

By addressing this gap, this study draws upon established theoretical frameworks, such as the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 2002) and social cognitive theory (Schmitt et al., 2018), to systematically examine the mechanisms underlying entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities. Specifically, it explores how psychological factors shape entrepreneurial engagement within this marginalized group. It focuses on the relationships and interaction effects among self-stigma, psychological resilience, self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial motivation. Using survey data from individuals with disabilities, this study employs a five-point Likert scale to measure key constructs and tests the proposed hypotheses through a binary structural equation modeling (SEM) approach using Mplus. The findings reveal that entrepreneurial self-efficacy, although widely viewed as a positive trait in mainstream research, may function differently in marginalized contexts. Among individuals with disabilities, higher levels of self-efficacy may amplify awareness of structural barriers, thereby reducing entrepreneurial motivation. By contrast, resilience plays a dual role: it weakens self-efficacy while significantly enhancing motivation. Additionally, self-stigma indirectly fosters entrepreneurial motivation through mediating pathways.

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature and advances the field of disability entrepreneurship by extending the theoretical and empirical understanding of entrepreneurial processes among individuals with disabilities. In addition, it offers practical insights for policymakers and entrepreneurship support programs. The findings may inform the design of inclusive entrepreneurship policies that address not only financial constraints but also psychological barriers, such as self-stigma and lack of self-efficacy. Additionally, this study provides recommendations for tailored interventions, including mentorship programs and network-building initiatives, to foster sustainable entrepreneurial engagement among individuals with disabilities.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background and reviews the relevant literature. Section 3 outlines the hypotheses and research model. Section 4 describes the research design, including data collection and measurement. Section 5 presents the results of the analysis. Section 6 discusses the findings based on existing research. Finally, Section 7 concludes by highlighting theoretical and practical implications, as well as directions for future research.

Background and literature reviewDisability entrepreneurshipAlthough research on disability and entrepreneurship has gained traction in recent years, much of the existing literature continues to adopt mainstream entrepreneurship theories without critical adaptation. These traditional frameworks typically portray entrepreneurs as autonomous, opportunity-seeking individuals who mobilize resources and respond flexibly to market conditions (Al-Mamary & Alshallaqi, 2022). However, whether this applies to entrepreneurs with disabilities remains unclear. Individuals with disabilities face distinct structural disadvantages, such as institutional discrimination, limited access to resources, and social stigma (Hsieh et al., 2019), which are often overlooked in mainstream entrepreneurship theories. Given the significant differences in experience, identity, and access between entrepreneurs with disabilities and those without (Jammaers & Williams, 2023), it is necessary to reassess the universality of these theories and explore whether they adequately capture the entrepreneurial realities of this marginalized group.

In response to these limitations, an emerging body of research has begun to challenge traditional assumptions and propose more inclusive and intersectional frameworks. For instance, Jammaers and Williams (2023) introduced the concept of “anomalous bodily capital,” which reconceptualizes disability not only as a limitation but also as a unique resource that can be leveraged in entrepreneurial activity. Similarly, research has increasingly positioned disability entrepreneurship within the broader paradigms of social and inclusive entrepreneurship, highlighting not only economic motives but also deeper drivers, such as autonomy, self-empowerment, and social inclusion (Norstedt & Germundsson, 2023; Vargas-Zeledon & Lee, 2024).

Contemporary studies in this field focus on several interrelated themes. First, the importance of policy and institutional support has been continuously emphasized. Scholars argue that the entrepreneurial participation of individuals with disabilities should be effectively promoted by establishing inclusive entrepreneurial projects, improving barrier-free infrastructure, and building a multi-level social support network (Norstedt & Germundsson, 2023). Second, the intersectionality of identities is receiving increased attention. Hidegh et al. (2023) argued that entrepreneurial identity among individuals with disabilities is shaped not only by disability itself but also by the interplay of gender, race, class, and other social categories, which together influence how individuals experience and respond to structural biases, such as ableism. Third, adaptive psychological mechanisms—such as resilience and self-efficacy—along with social support systems, have been identified as crucial factors enabling entrepreneurs with disabilities to overcome institutional barriers (Bagheri & Abbariki, 2017; Hsieh et al., 2019).

Given the importance of psychological adaptation mechanisms among individuals with disabilities—such as resilience, self-efficacy, and coping strategies—and the substantial differences in lived experience, access to opportunity, and identity formation between entrepreneurs with disabilities and those without, it becomes increasingly essential to scrutinize the assumptions underlying mainstream entrepreneurship research. Specifically, further empirical investigation is needed to determine whether the psychological factors widely considered to promote or hinder entrepreneurial behavior in the general population function in the same way for individuals with disabilities. Without such differentiated analysis, there is a risk of oversimplifying or misapplying theoretical constructs, which would fail to account for the structural inequalities, social stigma, and chronic uncertainty that uniquely shape the entrepreneurial trajectories of individuals with disabilities.

Entrepreneurial driveEntrepreneurial drive, which encompasses entrepreneurial self-efficacy and motivation, plays a pivotal role in shaping entrepreneurial behavior at the individual level (Kiani et al., 2023; McGee & Peterson, 2019; Schmutzler et al., 2019). While firm-level constructs, such as entrepreneurial orientation, emphasize strategic behaviors such as innovativeness, risk-taking, and proactiveness, entrepreneurial drive captures the internal psychological mechanisms that enable individuals to act on entrepreneurial opportunities (Kim & Jin, 2024; Kim & Zhao, 2024). These two perspectives complement one another by linking strategic orientation with individual agency in complex and dynamic environments.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy, defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to perform entrepreneurial tasks, is widely recognized as a core determinant of entrepreneurial intention and behavior (McGee & Terry, 2024). Rooted in social cognitive theory (Bullough et al., 2014), self-efficacy influences how individuals interpret opportunities, regulate emotional responses, and persist through challenges. High self-efficacy enhances individuals’ ability to manage uncertainty, devise innovative strategies, and sustain goal-directed action even under resource constraints (Santoro et al., 2020). It fosters positive affect and strengthens self-regulation by enabling individuals to recall prior successes and envision favorable outcomes, thereby reinforcing motivation and behavioral persistence (Cardon & Kirk, 2015; Kiani et al., 2023).

Entrepreneurial motivation, in turn, reflects the internalized drive that propels individuals toward entrepreneurial goals. According to the theory of planned behavior, motivation bridges the gap between intention and action, serving as the cognitive and emotional energy behind entrepreneurial engagement (Ajzen, 2002; Caliendo et al., 2023). Motivation is shaped by a constellation of personal and contextual factors, including goal clarity, self-regulation, and perceived opportunity structures. It transforms abstract aspirations into deliberate entrepreneurial behaviors and is widely acknowledged as a catalyst for opportunity exploitation and venture creation (Mahto & McDowell, 2018; Schmitt et al., 2018).

This study extends existing theory by investigating whether these relationships persist in the context of disability. Specifically, it examines whether higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy among individuals with disabilities consistently enhances motivation—or whether, under conditions of systemic constraint, heightened self-awareness of barriers may paradoxically reduce the drive to act. By exploring these dynamics, this research advances a more nuanced understanding of entrepreneurial drive and its boundary conditions in disadvantaged contexts.

Psychological resilience with disabilitiesWhile entrepreneurial drive is commonly understood as the core engine of entrepreneurial action, it does not operate in isolation—particularly for individuals facing systemic disadvantage. For them, psychological resilience often emerges as a critical factor that interacts with and potentially reshapes the mechanisms of entrepreneurial engagement.

Psychological resilience, defined as an individual’s capacity to maintain or regain mental health despite adversity, is a critical construct for understanding how individuals with disabilities navigate structural and psychological barriers (Ahmed et al., 2022; Nikolaev et al., 2020). Resilience is typically characterized by positive adaptation to stress, the ability to maintain a sense of purpose, and continued engagement in meaningful life activities (Bullough et al., 2014). While resilience is often viewed as a driver of entrepreneurial intention, its effects may differ in marginalized populations owing to persistent exposure to societal stigma, limited opportunities, and chronic marginalization (Miller & Le Breton-Miller, 2017; Renko et al., 2021). For instance, individuals who have developed high resilience over time may simultaneously possess an acute awareness of structural limitations that could temper their perceptions of entrepreneurial capability or increase risk aversion. In such cases, resilience may support emotional regulation and coping without translating into the confidence necessary for entrepreneurial action.

Individuals with disabilities often face multiple overlapping barriers, including physical limitations, institutional discrimination, and systemic exclusion. These conditions contribute to heightened psychological vulnerability, often manifested as self-stigma, which can both hinder and paradoxically stimulate entrepreneurial motivation (Lewis & Crabbe, 2024). As Trani et al. (2020) noted, the internalization of negative social perceptions—known as self-stigma—can erode self-worth, heighten depressive symptoms, and diminish the perceived capability to engage in goal-directed behavior (Langford et al., 2022). This psychological distress is compounded by limited access to supportive structures in education, employment, and healthcare systems, further inhibiting participation and opportunity-seeking behavior (Renko et al., 2016). Although self-stigma is generally perceived as a negative factor, in the context of disability it may paradoxically function as a “reverse mobilization mechanism” that stimulates intrinsic entrepreneurial drive. For instance, entrepreneurs with disabilities often develop a strong sense of goal orientation and self-empowerment to “prove themselves” and demonstrate their value and capabilities.

Hypotheses and research modelSelf-stigma refers to the internalization of negative societal beliefs and stereotypes, often resulting in shame, diminished self-worth, and behavioral withdrawal. For individuals with disabilities, self-stigma is frequently triggered by perceived injustice and discrimination in key life domains such as education, employment, and healthcare. This internalized stigma not only exacerbates psychological distress but also impairs cognitive and motivational functioning (Yu et al., 2023), which are crucial for entrepreneurial engagement. In the entrepreneurial context, self-stigma undermines confidence in one’s abilities, thereby reducing perceived entrepreneurial self-efficacy (Martin & Honig, 2020). Accordingly, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1) Self-stigma negatively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy in individuals with disabilities.

Psychological resilience, broadly defined as the capacity to adapt positively in the face of adversity, is widely acknowledged as a foundational psychological resource that enhances entrepreneurial cognition and behavior (Ahmed et al., 2022). For individuals with disabilities, resilience supports emotional stability, tolerance for ambiguity, and perseverance when faced with structural barriers (Yeshi et al., 2024). These adaptive traits are particularly vital for entrepreneurship, where uncertainty and setbacks are common. Existing research suggests that resilient individuals develop strong coping strategies, exhibit cognitive flexibility, and display enhanced problem-solving abilities—factors that bolster confidence in their capacity to pursue entrepreneurial action (Padilla-Meléndez et al., 2022). Resilience also contributes to entrepreneurial motivation by fostering optimism and goal persistence, even amid discrimination or resource scarcity (Hartmann et al., 2022). Based on this literature, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2H2 Resilience positively affects entrepreneurial self-efficacy in individuals with disabilities.

Hypothesis 3H3 Resilience positively affects entrepreneurial motivation in individuals with disabilities.

Social cognitive theory posits that individuals with high self-efficacy are more likely to pursue goals, persist in challenging environments, and maintain motivational focus due to their belief in successful task completion (Bullough et al., 2014). Within entrepreneurial settings, self-efficacy enhances opportunity recognition, risk management, and resilience under pressure (Santoro et al., 2020). Moreover, high self-efficacy facilitates positive affect, bolsters past-success recall, and enhances goal regulation, which, in turn, increases motivational intensity (Cardon & Kirk, 2015; Galindo-Martín et al., 2023). Self-efficacy is widely regarded as a precursor to entrepreneurial motivation and intention (Hsu et al., 2019; Neneh, 2022). Therefore, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 4H4 Entrepreneurial self-efficacy positively influences entrepreneurial motivation among individuals with disabilities.

Entrepreneurial motivation is a central psychological driver that propels individuals from intention toward action (Alam et al., 2019). Especially in marginalized contexts, motivation enables persistence, learning orientation, and proactive opportunity recognition, even in resource-constrained environments (Mahto & McDowell, 2018). Motivated individuals are more likely to engage in knowledge acquisition, goal setting, and iterative business development, which are essential for new venture creation. Previous research has consistently demonstrated that entrepreneurial motivation predicts actual entrepreneurial behavior by sustaining individuals’ engagement with entrepreneurial tasks and decision-making over time. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 5H5 Entrepreneurial self-efficacy positively influences entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities.

Hypothesis 6H6 Entrepreneurial motivation positively affects entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities.

These hypotheses are integrated into a unified research model, as depicted in Fig. 1, which outlines the theorized relationships guiding this study.

Methodology and research designSample and measurementThis study draws on data from the Disability Entrepreneurship Survey, a nationally representative dataset conducted in March 2024 and archived by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (Fan, 2024). The survey was designed to examine the entrepreneurial experiences and intentions of individuals with disabilities and captured responses from 318 participants. Respondents provided comprehensive information on demographic attributes, psychological constructs, and contextual variables. The variables included were entrepreneurial self-efficacy, resilience, entrepreneurial motivation, self-stigma, and family support—factors central to the theoretical framework guiding this study.

Because the primary aim of this research is to investigate psychological and environmental mechanisms underpinning entrepreneurial behavior—rather than disability-type-specific effects—participants were not categorized based on their type of disability. This approach enhances the generalizability of the findings by avoiding diagnostic sub-grouping, which could obscure broader psychological patterns. A rigorous cleaning process was employed to ensure data quality. Survey items that did not align with the theoretical framework were excluded to preserve conceptual clarity and measurement validity. Additionally, cases with missing responses were excluded, resulting in a dataset comprising exclusively complete cases. Following prior research indicating that entrepreneurial activity is most prevalent among individuals aged 30–44 years (Bosma et al., 2012), the sample was further restricted to respondents aged between 20 and 50 years. This criterion was employed to capture younger adults exploring entrepreneurial entry and mid-career individuals with relevant experience, yielding a refined analytic sample of 292 valid responses.

Entrepreneurial behavior was operationalized as a binary variable indicating the presence or absence of entrepreneurial activity. The four psychological predictors—entrepreneurial self-efficacy, resilience, entrepreneurial motivation, and self-stigma—were measured using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” These constructs were selected based on their theoretical relevance and empirical significance in prior entrepreneurship and disability studies. In particular, self-stigma—defined as the internalization of negative societal beliefs—has been shown to diminish self-worth and erode confidence in entrepreneurial capability (Lillis et al., 2010). This construct is particularly critical for understanding the psychological barriers that can deter entrepreneurial engagement among marginalized individuals. Conversely, resilience, conceptualized as the ability to adapt and persist despite adversity, has been positively associated with entrepreneurial persistence and adaptability, especially under conditions of uncertainty (Shore et al., 2024). The resilience scale assessed respondents’ capacity to cope with business setbacks, manage change, and maintain motivation in the face of challenges.

Analytical approachBy integrating these psychological constructs into a unified empirical framework, the research design allows for a nuanced analysis of how self-stigma and resilience affect entrepreneurial self-efficacy, motivation, and behavior among individuals with disabilities. This approach facilitates a more precise understanding of whether entrepreneurial self-efficacy functions as a universally enabling factor or, under certain conditions, may suppress motivation or inhibit entrepreneurial action. Moreover, the binary operationalization of entrepreneurial behavior provides a clear analytic distinction between those who have engaged in entrepreneurial activity and those who have not, thus enhancing the explanatory power of the model. Through this design, the study contributes to theoretical refinement and policy-oriented insights for supporting inclusive and equitable entrepreneurial ecosystems.

To examine the complex psychological processes that shape entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities, this study employs SEM, which is a robust statistical technique well suited for simultaneously estimating direct and indirect effects among latent constructs. For this study, SEM is particularly advantageous because it allows for the incorporation of mediating relationships—such as the role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy—while accounting for the binary nature of the dependent variable, entrepreneurial behavior (EB), through a logistic regression extension. Entrepreneurial behavior is modeled as a dichotomous outcome, where EB = 1 indicates engagement in entrepreneurial activity and EB = 0 indicates its absence. The probability of entrepreneurial behavior is modeled using a logit function:

where Xi represents the explanatory variables—self-stigma (SS), resilience (R), entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE), and entrepreneurial motivation (EM); β0 is the intercept, and βi are the estimated coefficients for each variable. This formulation enables a robust estimation of the relationship between psychological factors and the likelihood of engaging in entrepreneurial activity.Within the structural model, entrepreneurial self-efficacy is positioned as a central mediating construct that bridges psychological antecedents (self-stigma and resilience) and entrepreneurial outcomes. Self-efficacy reflects individuals’ beliefs in their capacity to execute entrepreneurial tasks, and its formation is theorized to be influenced by the negative internalization of stigma and the positive psychological resource of resilience. Accordingly, self-efficacy is modeled as a function of self-stigma and resilience as follows:

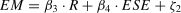

where SS denotes self-stigma, R denotes resilience, and ζ1 captures the residual variance unexplained by these two predictors. The coefficients β1 and β2 quantify the extent to which these psychological factors influence perceived entrepreneurial capability. This equation enables an empirical test of whether stigma undermines confidence and whether resilience enhances it, as commonly theorized in the entrepreneurship literature.Entrepreneurial motivation, another core psychological construct, represents the internal drive that sustains entrepreneurial intention and action. In this model, motivation is hypothesized to be influenced by resilience and self-efficacy, aligning with existing frameworks in social cognitive theory. This relationship is expressed as:

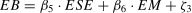

where β3 represents the strength of the direct relationship between resilience and motivation, while β4 captures the mediating role of self-efficacy in enhancing or weakening motivational drive. ζ2 accounts for the portion of entrepreneurial motivation not explained by these predictors. This formulation reflects the belief—prevalent in the literature—that resilience and self-efficacy are foundational for fostering sustained entrepreneurial ambition, particularly under challenging conditions.Finally, this study theorizes that entrepreneurial behavior, the ultimate dependent variable, is driven by entrepreneurial self-efficacy and motivation. In line with previous research, these two factors are positioned as the final mediators that translate psychological traits into entrepreneurial action. This is formalized as follows:

In this specification, β5 and β6 quantify the relative contributions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and motivation to entrepreneurial behavior, while ζ3 represents residual variance not captured by the model. Through this path analysis, the model enables the decomposition of total effects into direct and indirect components, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of how psychological barriers (e.g., self-stigma) and enablers (e.g., resilience) influence entrepreneurial behavior through mediating psychological mechanisms.

By integrating these components into a unified analytical framework, the study provides a theory-driven, empirically testable model of entrepreneurial behavior in a marginalized population. This approach allows for the exploration of whether self-efficacy universally enables entrepreneurial engagement or whether, under certain structural conditions, it may reduce motivation and hinder action. The SEM framework thus facilitates a deeper understanding of the interplay between psychological traits and entrepreneurial outcomes, offering insights that are theoretically grounded and methodologically rigorous.

Empirical resultsData analysisTo assess the psychometric properties of the constructs and evaluate the structural model, a combination of descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis, and SEM was employed. Descriptive and preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS 27, while confirmatory and structural modeling procedures were executed in Mplus 8.3. This analytical strategy allowed for a robust evaluation of measurement reliability and the hypothesized relationships between psychological and behavioral variables.

As Table 1 shows, descriptive statistics support the assumption of approximate normality, with skewness values below 2 and kurtosis values below 7 (West et al., 1995). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy exhibited relatively low means (2.49, 2.29, and 2.29), whereas resilience (3.55, 3.54, and 3.57) and entrepreneurial motivation (3.68, 3.71, and 3.86) were substantially higher. These patterns suggest that although individuals with disabilities may express limited self-confidence in entrepreneurial tasks, they possess strong adaptive and motivational capacities—factors that may serve as critical psychological resources in the entrepreneurial process.

Descriptive statistics of latent variables among individuals with disabilities.

To examine the dimensionality and internal consistency of the scales, an EFA was conducted (Table 2). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was 0.842, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ² = 2092.66, df = 66, p < 0.001), confirming sampling adequacy. As Table 2 reports, four latent factors emerged, which were consistent with the theoretical structure, and all factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70. Internal reliability was confirmed with Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.791 to 0.899, indicating satisfactory consistency across all constructs.

Exploratory factor analysis.

The confirmatory factor analysis results indicate a well-fitting measurement model (see Table 3). The chi-square value was 85.978 (df = 48, p = 0.0006). Although the chi-square test is significant, it is sensitive to large sample sizes; thus, additional fit indexes are considered. The RMSEA value of 0.052 (90 % CI: 0.034–0.070), along with the CFI (0.982), TLI (0.975), and SRMR (0.031), confirms an excellent fit between the measurement model and the observed data. The baseline model’s chi-square value of 2135.317 (df = 66, p < 0.001) further supports the adequacy of the measurement model. Factor loadings demonstrated strong item–construct relationships, with most exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7. Composite reliability values exceeded 0.7, and average variance extracted values surpassed 0.5 for all constructs, confirming internal consistency (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

Confirmatory factor analysis.

SEM was used to examine the relationships between psychological antecedents and entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities. The proposed model demonstrated excellent fit to the data (χ² = 75.589, df = 59, p = 0.0716; RMSEA = 0.031; CFI = 0.966; TLI = 0.956; SRMR = 0.033), indicating that the hypothesized relationships among constructs—self-stigma, resilience, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, entrepreneurial motivation, and entrepreneurial behavior—were statistically robust and conceptually well aligned. As Table 4 and Fig. 2 show, the results partially confirm theoretical expectations and reveal significant departures that call for further conceptual reflection.

Standardized path coefficients and hypotheses acceptance/rejection outcomes.

Self-stigma was found to significantly reduce entrepreneurial self-efficacy (H1: β = −0.111, p = 0.009), reaffirming prior findings that internalized social stigma negatively affects individuals’ belief in their entrepreneurial capabilities. As expected, resilience positively influenced entrepreneurial motivation (H3: β = 0.369, p < 0.001), highlighting its function as a psychological resource that supports persistent entrepreneurial intent despite adversity. However, entrepreneurial self-efficacy did not have a statistically significant direct effect on entrepreneurial behavior (H5: β = −0.113, p = 0.319), suggesting that capability beliefs alone might not be sufficient to translate into entrepreneurial engagement under conditions of structural constraint. In contrast, entrepreneurial motivation had a significant positive effect on entrepreneurial behavior (H6: β = 0.243, p = 0.037), indicating that motivational drive, rather than perceived ability, is more directly linked to entrepreneurial action in this population.

Notably, this study identified two unexpected yet theoretically significant findings. Contrary to the initial hypothesis, resilience was negatively associated with entrepreneurial self-efficacy (H2: β = −0.604, p < 0.001), suggesting that while individuals may develop resilience to cope with adversity, this adaptive capacity does not necessarily translate into enhanced self-confidence in entrepreneurial contexts. Instead, resilience may amplify awareness of systemic limitations, leading to a more realistic but potentially discouraging assessment of entrepreneurial viability. Similarly, entrepreneurial self-efficacy exerted a negative effect on entrepreneurial motivation (H4: β = −0.467, p < 0.001), challenging conventional models that treat self-efficacy as a universally motivating force. This counterintuitive outcome may reflect a heightened sensitivity to institutional barriers and risk, particularly among those who feel more capable and attuned to the limitations they must confront. These results challenge the generalizability of prevailing entrepreneurial psychology frameworks and underscore the need for more context-sensitive theoretical models that consider the unique psychological dynamics of marginalized groups.

DiscussionThis study examined the psychological underpinnings of entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities, drawing on established constructs such as self-stigma, resilience, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and motivation. The tested structural model provides empirical confirmation of some canonical relationships and novel theoretical insights that challenge the generalizability of conventional entrepreneurship models. Psychological research in entrepreneurship often assumes a universal model in which internal capacities directly translate into behavioral outcomes; this study investigates whether such assumptions hold under persistent structural exclusion. By focusing on a marginalized population, this research provides a critical opportunity to explore how context shapes cognition and how internal traits may function differently when filtered through adversity and discrimination.

The findings show that self-stigma significantly reduces entrepreneurial self-efficacy (H1), which aligns with social cognitive theory and stigma research (Martin & Honig, 2020). This supports the interpretation that internalized negative perceptions impair an individual’s belief in their capacity to act. For individuals with disabilities, this relationship is particularly consequential, as systemic discrimination and negative societal attitudes often form the background conditions that shape daily interactions. Over time, the internalization of such signals can lead to chronic self-doubt and risk aversion, undermining the confidence required to initiate or sustain entrepreneurial action. Similarly, consistent with prior studies (Ahmed et al., 2022; Bullough et al., 2014; Nikolaev et al., 2020), this finding supports the conceptualization of resilience as a psychological enabler of entrepreneurial motivation (H3), reaffirming that resilience acts as an adaptive resource that sustains psychological drive amid adversity. Resilient individuals often maintain a long-term orientation and can better cope with the ambiguity and instability associated with entrepreneurship. Additionally, consistent with the established assumption in the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 2002; Caliendo et al., 2023), motivation acts as a proximal determinant of entrepreneurial behavior, even within the context of individuals with disabilities (H6). In challenging environments, motivation can function as an affective bridge between intention and action, empowering individuals to persevere despite external barriers. By fostering psychological resilience and reinforcing goal commitment, motivation enables people to translate entrepreneurial intent into sustained action, even when faced with limited resources, societal stigma, or institutional exclusion.

Interestingly—contrary to prior findings in general entrepreneurship research and social cognitive theory (Bullough et al., 2014; Neneh, 2022)—entrepreneurial self-efficacy did not directly predict entrepreneurial behavior (H5). This finding suggests that confidence alone is insufficient to catalyze action under structural exclusion, even if necessary. These results confirm that while some psychological processes operate similarly across populations, their effects are shaped and sometimes muted by external realities in marginalized contexts. This divergence calls for a more context-sensitive interpretation of self-efficacy, in which structural limitations, rather than individual beliefs alone, critically determine whether psychological intentions translate into behavioral outcomes.

Additionally, two findings diverged significantly from the established theoretical expectations. First, contrary to the prevailing findings (Bullough et al., 2014; Chadwick & Raver, 2020), resilience does not always exhibit a positive relationship with entrepreneurial self-efficacy (H2). In highly challenging entrepreneurial environments, resilience may be negatively associated with entrepreneurial self-efficacy. A plausible explanation for this can be found in the lived experiences of individuals with disabilities. Prolonged exposure to challenging environments may lead them to develop resilience as an adaptive mechanism. However, this process may also increase their sensitivity to external barriers—such as bureaucratic hurdles, social discrimination, and inadequate institutional support—which, in turn, may erode their confidence in their entrepreneurial capacity. Another possible explanation is that, despite possessing strong resilience, individuals with disabilities who remain in a prolonged state of negative emotion may experience emotional exhaustion, gradually diminishing their belief in their own abilities (Cabrera-Aguilar et al., 2023). Therefore, along with resilience, a supportive policy environment and promotion of mental well-being are crucial.

Second, challenging the findings of most prior entrepreneurship studies based on social cognitive theory (Bullough et al., 2014; Neneh, 2022), this study reveals that higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy may suppress entrepreneurial motivation (H4). A plausible explanation for this is that elevated self-efficacy often entails heightened sensitivity to both opportunities and risks. In marginalized entrepreneurial contexts, this acute risk awareness can trigger a fear of failure, resulting in more cautious and hesitant behavior (Galindo-Martín et al., 2023). In other words, although individuals perceive themselves as highly capable, their heightened awareness of potential threats in the entrepreneurial process may undermine their willingness to act and weaken their intrinsic drive—making high entrepreneurial self-efficacy a potential barrier to entrepreneurial motivation. These unexpected outcomes point to a deeper theoretical tension: the same psychological resources that are meant to empower may also constrain when filtered through structural disadvantage.

The findings of this study present a significant challenge to the assumptions established within mainstream psychological models of entrepreneurship. First, psychological resources such as resilience and self-efficacy do not operate in a vacuum; their functions are profoundly shaped by structural exclusion and identity-based marginalization. Thus, directly applying conventional psychological mechanisms to the context of entrepreneurs with disabilities may result in theoretical bias and practical misinterpretation. Second, compared with entrepreneurial motivation, self-efficacy demonstrates clear limitations in predicting entrepreneurial behavior among individuals with disabilities. This suggests that efforts to foster entrepreneurship in this population should prioritize the stimulation of intrinsic motivation rather than merely enhancing perceived capability. Finally, while internalized stigma negatively affects self-efficacy, it can indirectly exert a positive influence on entrepreneurial motivation. This mechanism reveals that the motivation of entrepreneurs with disabilities may stem less from confidence in their abilities and more from the drive to prove themselves. Taken together, these findings underscore the need for a more context-sensitive theoretical approach to entrepreneurship—one that can account for how identity, environment, and perceived constraints interact to shape entrepreneurial behavior among marginalized groups.

ConclusionThis study makes several significant contributions to the theory and practice of entrepreneurship among individuals with disabilities. Theoretically, it challenges the assumption of the universal applicability of psychological mechanisms embedded in dominant frameworks such as the theory of planned behavior and social cognitive theory. Our findings indicate that these theories have limited explanatory power in contexts shaped by systemic constraints, thus contributing to critical streams of inclusive and disability-oriented entrepreneurship research. By situating entrepreneurial behavior within the lived realities of marginalized groups, this study underscores the need to incorporate contextual diversity into entrepreneurship theory.

Moreover, this research sheds new light on the complex role of psychological constructs—particularly self-stigma, resilience, and motivation—in the entrepreneurial decision-making processes of individuals with disabilities. Contrary to conventional assumptions, we find that resilience might not always correlate positively with entrepreneurial self-efficacy and that high self-efficacy does not necessarily lead to greater motivation. These nuanced insights deepen the understanding of how identity is formed and maintained in the face of social stigma, structural exclusion, and psychological strain. By reframing these constructs within a context-sensitive analytical framework, this study lays the groundwork for more inclusive, realistic models of entrepreneurial behavior that respond to systemic inequality and social structural constraints.

In practice, our findings call for a fundamental shift in the design and delivery of entrepreneurial support for individuals with disabilities. Rather than assuming a direct link between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial action, support programs should prioritize the cultivation of intrinsic motivation as the core driver of entrepreneurial behavior. Policymakers and practitioners must move beyond surface-level assessments of capability and implement systems that foster sustained engagement and self-determined participation. This includes targeted psychological support mechanisms to help entrepreneurs manage frustration, fear of failure, and emotional stress resulting from persistent uncertainty and social exclusion.

Additionally, structural interventions—such as safe exit strategies and re-employment guarantees—can alleviate the psychological risks associated with entrepreneurship and enhance long-term commitment. To translate psychological readiness into concrete action, it is essential to offer customized training, access to financial and informational resources, and networking opportunities tailored to the unique needs of entrepreneurs with disabilities. Institutionalizing this support through integrated policy frameworks would promote resource coordination, enable greater participation, and foster a more inclusive and equitable entrepreneurial ecosystem. Ultimately, these efforts would contribute to building a diverse and socially responsive economy that values the contributions of all members.

Limitations and future research directionsThis study offers new insights into the psychological dynamics of entrepreneurship among individuals with disabilities. However, it has some limitations. The cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw conclusions about changes over time, and the national scope of the sample may constrain generalizability. Future research would benefit from longitudinal and cross-cultural approaches exploring how different disability types and contextual factors shape entrepreneurial experiences. Despite these limitations, this study lays the foundation for more inclusive and context-sensitive entrepreneurship research.

Building on this foundation, future studies could further investigate how individual psychological mechanisms interact with institutional environments, such as welfare policies, support programs, and societal attitudes toward disability. In particular, examining whether the relationships observed in this study—such as the non-linear dynamics between resilience, self-efficacy, and motivation—persist across varying institutional or policy contexts would enhance theoretical robustness. Additionally, qualitative or mixed-methods approaches could offer richer accounts of how self-stigma and psychological strain are experienced and managed over time, thus complementing the quantitative findings of this study. Such extensions would not only validate and elaborate on the current model but also contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how individuals with disabilities navigate entrepreneurial pathways under structural constraints.

CRediT authorship contribution statementHuan Meng: Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Junic Kim: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) under the metaverse support program to nurture the best talents (IITP-2024-RS-2023–00256615) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT).