Based on the provincial panel data of 31 provinces in China from 2003 to 2022, this study constructed an evaluation system for the resilience of the food industry. We used the ordinary least squares model to empirically analyse the impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. Furthermore, we applied the spatial Durbin model with spatiotemporal double fixed effects to investigate the potential spatial spillover effects of technological innovation in food production on industry resilience. The results indicate the following key points: (1) Technological innovation in food production has a positive influence on the resilience of the food industry, as well as on its risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability. However, this long-term impact exhibits a distinctly diminishing marginal character. (2) Technological innovations in food production increase the resilience of the food industry by optimising the employment structure. (3) Digital inclusive finance and its associated credit and payment services can enhance the positive impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. Notably, digital inclusive finance is characterised by significant gradient differences and diminishing margins. (4) Technological innovation has a significant siphoning effect on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces. (5) Analyses of heterogeneity indicate that technological innovation has a significant siphoning effect on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces in the eastern, central and western regions. Meanwhile, a significant spillover effect is evident in the north-eastern region. This study’s main contribution is providing empirical evidence to inform regionally differentiated policies aimed at improving the level of agrotechnological innovation and the resilience of the food industry.

Food security is closely linked to people’s well-being and social stability, a goal that various countries have long pursued (Gao & Yao, 2022). However, the current external situation has worsened because of geopolitical conflicts, public health events and climate change. Supply shocks, such as resource and environmental constraints and structural contradictions, have also persisted. These challenges pose serious risks to global food security (Albert, 2023). For example, global food insecurity peaked at 11.9 % between 2020 and 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic (World Bank, 2023). Furthermore, 2024 was the hottest year on record (WMO, 2025). Climate change has intensified extreme weather events, significantly affecting the global food industry (Li & Song, 2022). If trends remain unchanged, the Sustainable Development Goal of ending hunger by 2030 will not be achieved (FAO et al., 2023). With government policy support for food security, China has completed two consecutive decades of increased grain production as of 2024. However, because China has a low level of agricultural mechanisation and agricultural technology, the international competitiveness of most agricultural products is insufficient and the resilience of the food industry is low (Lee et al., 2024). The urgent need to develop a resilient and competitive food industry system in China is now a pressing concern.

In recent years, the concept of resilience, developed in ecology, has provided a new perspective for the sustainable development of the modern food industry (FAO, 2021). Food industry resilience refers to the ability of a food system to withstand external shocks, recover quickly from shocks and shift to new growth paths through internal structural adjustments (Zuo & Ye, 2024). Scholars and organisations have conducted numerous studies on the resilience of the food industry, including its connotations (FAO, 2021), evaluation criteria (FAO, 2021) and influencing factors (Hamilton et al., 2024; Marrero, 2022). The Strategic Framework 2022–31 issued by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations also proposes focusing on building a more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable agricultural food system (FAO, 2021). Therefore, enhancing the resilience of the food industry has become a priority for ensuring global food security.

Technological innovation in the form of spillovers allows for incremental rewards and is a necessary ingredient for sustained economic development (Parubets, 2022). Technological innovation in food production involves introducing new factors and upgrading management methods, which can improve land quality and increase food output. Furthermore, it can optimise labour structures and industrial layouts, promoting the sustainable development of the food industry. For this reason, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2022) published its Science and Innovation Strategy, which aims to harness science and innovation to contribute to more efficient, inclusive, resilient and sustainable agrifood systems. Many researchers have also demonstrated that increasing food production and achieving high-quality agricultural development are closely linked to technological innovation (Le, 2005; Shi et al., 2024; Sharma et al., 2025). In recent years, China has faced several food security challenges, including high agricultural production costs (Wang et al., 2020), limited arable land and water resources (Song et al., 2023) and the unsustainable practice of high-intensity chemical agriculture (Wang et al., 2019; Xiong & Zhao, 2024). The promotion of agricultural transformation through technological innovation and the narrowing of regional gaps in agricultural productivity through the diffusion of agricultural technology are crucial. Therefore, this study uses provincial panel data from 31 provinces in China from 2003 to 2022 to construct a food industry resilience evaluation system, examines how technological innovation in food production affects the resilience of the food industry, and explores whether there is a spatial spillover effect related to this impact. This study provides empirical evidence for optimising food security policies and promoting high-quality food industry development.

This study is committed to possible marginal innovations in the following aspects. First, the concept of resilience is introduced into the food system to analyse the scientific connotation and constituent elements of resilience. This is an expansion of resilience research. Second, this study constructs a comprehensive framework for the resilience of the food industry, encompassing risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability, which serves as a refinement of the resilience evaluation criteria. Third, this study innovatively explores the mechanism by which technological innovation affects the resilience of the food industry by examining the influence path through a multidimensional mechanism analysis. Fourth, the spatial Durbin model is used to examine the spatial effects of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry, providing empirical support for the promotion of integrated and coordinated development of the resilience of the inter-regional food system.

Literature reviewResilience of the food industryThe term resilience, first coined in the field of ecology by Holling (1973), refers to an ecosystem’s ability to return to a steady state or equilibrium following disturbances caused by natural hazards. In many cases, resilience is associated with a system’s ability to withstand and adapt to disturbances (Fan et al., 2014), as well as its rate of recovery after a disturbance occurs (Holling, 1996). For example, MacGillivray and Grime (1995) used the rate of recovery of plant systems from natural disasters to study the resilience of such systems. The concepts of stability, robustness and vulnerability have been studied separately in the existing literature (Huyghe et al., 2016). However, these factors serve as subtle indicators of how a subject’s dynamic processes respond to shocks. In contrast, resilience is a pragmatic, overarching structure that denotes a subject’s ability to withstand disturbances (Bullock et al., 2017). Subsequently, scholars such as Fujita and Thisse (2002) introduced the concept of resilience into economics and used this endogenous ability to restore homeostasis after disturbances to explain the intrinsic mechanisms of economic activities. Numerous scholars have since developed a unified understanding of the connotations of economic resilience. It is defined as the ability of an economic system to withstand external shocks, maintain its structure and functions and recover quickly through diverse response measures (Cellini & Torrisi, 2014). As research has progressed, studies on agricultural resilience have emerged. Agricultural economic resilience is an agricultural system’s ability to maintain its original characteristics and core functions after experiencing a shock (Folke, 2006). Research on the measurement (Belsare et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2019), influencing factors (Birthal & Hazrana, 2019) and realisation paths (Marrero et al., 2022) of the resilience of the agricultural economy has gradually emerged, providing practical solutions for its high-quality development.

Resilience thinking can significantly contribute to food security and sustainable development in the food industry (Naylor, 2009; Prosperi et al., 2015). Current research on resilience in the food industry has focused on three key areas. The first is the definition of resilience in the food industry. The food industry’s resilience refers to its ability to withstand unanticipated shocks (e.g. natural disasters, policy directions and market changes) while maintaining system stability and providing sufficient, appropriate and accessible food for all. Food system resilience interacts across scales and has a temporal dimension with threshold effects (Tendall et al., 2015). The State of Food and Agriculture 2021, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, suggests that resilience is the ability of the food industry to withstand disruptive factors, ensure access to adequate, safe and nutritious food on a long-term and sustainable basis, and sustain the livelihoods of food industry participants (FAO, 2021). The second is the evaluation criteria for the resilience of the food industry. The evaluation criteria for food industry resilience are derived from the measurement of economic resilience. Zobel and Khansa (2014) introduced robustness to shocks and rapidity of the recovery process to visualise resilience and used different combinations of these two metrics as a guide to decision-making. Martin (2012) proposed that the process of economic resilience to recessionary shocks consists of resistance, recovery, restructuring and renewal, based on which most scholars have conducted numerous studies. In their evaluation of agricultural resilience, Cabell and Oelofse (2012) compiled 13 indicators that encompass various attributes of the agricultural system, including the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of the landscape and the human resources available on the farm. Miranda et al. (2019) constructed measures of robustness, adaptability and transformability to assess agricultural system resilience. There are fewer studies on the evaluation of food industry resilience. Yang and Xu (2015) constructed four dimensions—robustness, redundancy, resourcefulness and rapidity—to measure food industry resilience. Government assistance was introduced as a recovery method for food processors during the recovery phase. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2021) developed a set of indicators to evaluate the resilience of the food industry at the country level. These indicators focus on four dimensions: agricultural primary production, agricultural trade, dietary sources and transportation networks. They help assess how well a national agrifood system can withstand shocks and stresses. The third is the factors affecting food industry resilience. Numerous studies have demonstrated that crop variety, diversity of production patterns and diversification of trading partners contribute to improved food industry resilience (Eder et al., 2024; Marrero, 2022). For example, engaging in various economic activities helps mitigate shock risks and enhance economic resilience (Frenken et al., 2007). Increases in labour productivity are central to shaping the response of food security systems to shocks (Segbefia et al., 2023). These improvements are linked to the economic size of food producers (Cheng et al., 2019), the composition of inputs used (Ansari et al., 2023; Hamilton et al., 2024), the adoption of technology (Yuko et al., 2018) and the training of farmers (Carlisle, 2014; Pelletier et al., 2016). Healthy agroecosystems are fundamental to building resilience in the food industry. They play a crucial role in improving soil conditions (Marrero et al., 2022; Rivest et al., 2013) and in maintaining the diversity of wild bees, which provide pollination services (Potts et al., 2016). Furthermore, well-connected food supply chains and transport networks (Yu & Zhang, 2019) and strong human capital (Kabbar et al., 2020) contribute to the overall resilience of the food industry.

Technological innovation spilloverA growing number of studies have captured and measured the spillovers of technological innovations. Uurluay and Kirikkaleli (2022) concluded that technological innovation increases the availability of cutting-edge technology in high-income economies, with co-integrating associations with education, public funding and life expectancy. Marchesi and Tweed (2021) and Aydin and Degirmenci (2024) both concluded that innovation promotes circular economy development and sustainable development. Meanwhile, the spatial agglomeration of technology leads to spatial distance differences in technological innovation spillovers (Davelaar & Nijkamp, 1986). For example, Keller and Wolfgang (2002) used innovation data from OECD member countries from 1970 to 1995 to study the spillover effects of geographically based R&D expenditures. They noted that innovation spillovers increased as geographic distance decreased. Bottazzi and Peri (2003), using the same technique, calculated that technological spillovers in the European region between 1977 and 1995 existed only within a distance of 300 km. Tang et al. (2022) demonstrated that urban hierarchy and geographical proximity have effects on knowledge spillovers, whereas administrative boundaries have the strongest inhibiting effect on knowledge spillovers. Radmehr et al. (2024) studied the spatial spillover effect of green technology innovation and concluded that such innovation is more inclined towards promoting domestic ecological sustainability. The study by Ding et al. (2024) on China reached the same conclusion: technological innovation plays a significant role in driving green development in the middle and upper reaches of the Yangtze River Economic Belt. In addition, existing studies have highlighted that the obstruction of inter-regional factor flows is a significant contributor to economic disparity (Lessmann, 2014). It is necessary to break down barriers to factor flows and promote cross-regional sharing of technological factors to narrow regional economic gaps.

Impact of technological innovation on food industry resilienceTechnological innovation is a key driver of industrial structural adaptation. Numerous studies have shown that technological innovation is a crucial driver of sustained growth in food production (Sarfraz et al., 2023) and is closely linked to food industry resilience. For example, technological innovations such as the cultivation of high-quality germplasm, the establishment of germplasm repositories and soil testing and formulation technologies can help crops resist pests, diseases, adversity and climate change (Birthal et al., 2015). Technological innovations in food mechanisation and automation have promoted the substitution of machines for human labour (Peng et al., 2021), which can improve the adaptability and productivity of food crops. Some scholars have also noted that technological innovation facilitates the rational allocation of resources, which can promote grain production to reduce costs, increase efficiency and enhance the total-factor productivity of grain (Zheng et al., 2023). Furthermore, technological innovation can reduce the carbon emission intensity of food production and promote green production transformation and sustainable development of the food industry. For example, Li and Li (2022) concluded that technological innovation can mitigate the impact of climate change on water resources for agriculture and food production. Shi et al. (2024) argued that technological innovations can effectively increase agricultural carbon productivity. In addition, Gong et al. (2023) also found that specialty seed innovation can promote green food production.

The research on agricultural science, technology and innovation and economic resilience is extensive and provides important insights for this study. However, some limitations exist. First, few studies have focused on technological innovation in the food industry. Meanwhile, research on industrial resilience has primarily focused on resource-based cities or industries with prominent conflicts. The research content mainly focused on industrial resilience assessment and optimisation strategies, with limited empirical research on food system resilience. In addition, although research on the spatial spillovers of agricultural technological innovations has gradually emerged, the impact of such spatial spillovers on the resilience of the food industry requires further exploration. Second, existing studies on food system resilience have primarily been conducted at production, supply chain, and ecological levels and they lack a holistic view of the food system. A system of indicators for assessing the resilience of the food industry has not yet been widely agreed upon. Third, there are fewer horizontal and vertical comparisons and correlation analyses of provincial food industry resilience and industrial resilience. This study constructs a provincial food industry resilience evaluation index system to measure the role mechanism and spatial spillover effect of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry, providing decision-making support to enhance the capacity for technological innovation in the food industry and advance its resilience.

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesesThe connotation of food industry resilience serves as the starting point for studying the mechanism by which technological innovation affects food industry resilience. Starting from the region’s theory of the adaptive cycle, Martin (2012) categorised the internal mechanisms of economic resilience into four processes: resistance, recovery, restructuring and renewal. Resistance refers to a region’s ability to mitigate losses after a crisis, and its strength reflects the economy’s sensitivity and vulnerability to external shocks. Recovery is the ability to self-adjust and recover after a crisis. Restructuring is the ability of an economy to reallocate its internal resources and optimise its economic structure after self-regulation. Renewal is the ability of an economy to discover new sustainable development paths following policy guidance, resource integration and optimisation of economic structures. Based on Martin’s theory of economic resilience, combined with the characteristics of food production, this study divides the resilience of the food industry into risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability.

Technological innovation can enhance the risk resistance of the food industry. The economic system can self-organise, and the size of its self-organising ability, to some extent, affects the system’s ability to withstand shocks. First, food productivity can be increased through the development and use of good seeds, medicines, fertilisers and technologies (e.g. mechanical equipment and biotechnology). Second, technological innovation can improve the efficiency of inputs and the quality of outputs, thereby contributing to the growth of food production and the transformation of the food industry. Third, increased technological innovation has led to the differentiation of new sectors. A refined division of labour can increase the degree of specialisation in the food industry, leading to a greater diversification of food varieties and reducing the production risks associated with uncertainties in the external environment of agricultural production.

Technological innovation can enhance the adjustment and recovery of the food industry. From a micro-perspective, the ability to innovate in technology reduces production costs by optimising the allocation of resources, which improves organisational management efficiency and stabilises organisational development. From a macro-perspective, the emergence of new technologies and processes alters the demand and supply structure of society, promoting enrichment of the industrial structure and industrial-scale expansion. Furthermore, technological innovation can lead to the continuous improvement of food products and services, the promotion of market competition and the improvement of the food market. In short, technological innovation can stabilise the food industry at multiple levels, making it easier for countries to quickly adapt and restore the status quo after external shocks.

Technological innovation can enhance the sustainability of the food industry. Schumpeter’s theory of innovation states that innovation involves building new organisations on old ones. This self-renewal ability corresponds to the ability of the food industry to discover new sustainable development paths after resource consolidation and structural optimisation. In the food industry, abandonment of the original traditional production model with high-factor inputs and a shift to a sustainable production model that upholds the concept of green production and adopts green production technology represents a renewal process. In this process, support for scientific and technological innovation is crucial, including soil testing and formulation technology, water-saving irrigation technology and other green agricultural technologies that can reduce carbon emissions from food production and surface source pollution. In the context of sustainable development, the food industry faces reduced resource and environmental constraints, leading to lower levels of environmental pollution during food production. This shift promotes the sustainable growth of the food industry. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 1 as follows:

H1: Technological innovation in food production positively impacts food industry resilience.

H1a: Technological innovations in food production positively impact risk resistance in the food industry.

H1b: Technological innovation in food production positively impacts the adjustment and resilience of the food industry.

H1c: Technological innovation in food production positively impacts food industry sustainability.

Scholars such as Acemoglu (1998, 2002) proposed the concept of skill-biased technical change (SBTC). As demonstrated by the fact that technological progress is biased more in favour of increased demand for skills and higher income changes (Acemoglu, 2002), SBTC raises the relative marginal output of technology. Subsequently, a significant increase in the supply of skilled labour leads to a rapid decline in the short-term skill premium. This provides incentives for producers to invest in additional equipment that complements skilled labour more effectively, thereby contributing to the occurrence of SBTC (Acemoglu, 2002). According to SBTC, agricultural technological innovation promotes the transformation of low-skilled jobs into high-skilled ones, improves employees’ digital literacy and skill levels and establishes a new employment pattern that involves skill upgrading and job creation. This indicates that technological innovation can enhance human capital structures by increasing the marginal productivity of highly skilled labour. SBTC influences food industry resilience by optimising the employment structure in three ways. First, agricultural technology has a displacement innovation effect. The increased use of agricultural machinery has reduced the demand for unskilled labour in traditional seeding and harvesting, thus increasing the elasticity of substitution for traditional jobs. This has prompted farmers to upgrade their skills through vocational training, which is more likely to enhance the marginal output of technological factors. Second, SBTC exhibits a bias towards skilled labour (Krusell et al., 1997). Technological innovations in agriculture have increased the demand in the food industry for highly skilled personnel (e.g. agricultural data analysts and farm machinery maintenance engineers). Furthermore, the skill premium incentivises the industry to invest in human capital. Highly skilled labour is typically better able to adapt to innovation, thereby reducing the marginal adjustment costs associated with adopting technology (Caselli & Coleman, 2006). Furthermore, they can drive technological innovation and process optimisation within the industry, thereby enhancing the ability to adopt technological innovations locally and improving industry resilience. Third, the optimisation of the employment structure promoted by SBTC will also attract more capital, innovative resources and high-quality labour, creating a positive feedback loop of industrial resilience. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 2 as follows:

H2: Changes in employment structures mediate the role of technological innovation in food production and the resilience of the food industry.

Based on the dynamic capability theory and resource dependence perspective, food import dependence plays a key mediating role in the relationship between technological innovation in food production and industrial resilience. Technological innovation, as a dynamic capability reconfiguration element of the industry, can change the resource dependency structure by upgrading localised productive capacities. Specifically, agricultural technological innovations, such as vertical farming, modular planting systems, green grain storage technologies and high-standard warehousing facilities, have significantly enhanced local production capacity and warehousing ability, leading to a gradual breakthrough in spatial and temporal constraints on food supply and reducing dependence on external food sources. As the mediating variable of food import dependency declines, the impact of trade policy uncertainty on the local market weakens, the risk of cross-border supply chain disruptions is mitigated and the food system’s resilience to external shocks is significantly enhanced. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3 as follows:

H3: Food import dependence has a mediating effect on the relationship between technological innovation in food production and food industry resilience.

Based on the dual perspective of financial constraint theory and innovation diffusion theory, digital inclusive finance creates a positive moderating mechanism between technological innovation in food production and industrial resilience by reconfiguring the transmission constraints of technological innovation. There is a significant credit rationing imbalance in the traditional rural financial market, resulting in small- and medium-sized farmers and new business entities generally facing financial barriers to the adoption of technological innovation. Digital inclusive finance uses the internet, big data, artificial intelligence, blockchain and other technologies to optimise inclusive financial service models and improve credit approval and risk management models. Thus, it can enhance the availability and quality of financial services for agricultural business entities, improve agricultural crop insurance coverage and protection levels and crack the bottleneck of financial constraints introduced by technology. Specifically, first, digital inclusive finance reduces the marginal cost of capital-intensive agricultural technology investments, such as vertical farming systems, by increasing credit availability. The innovation and proliferation of digital financial tools, such as internet insurance, can mitigate the risks associated with the adoption of agricultural technology. Both pathways can facilitate the adoption of agricultural technology, promote the transformation and upgrading of the food industry and improve the food industry’s ability to withstand risks. Second, the ease of use and speed of digital financial inclusion can enable agricultural enterprises to respond to external shocks in a timely manner, thereby improving the food industry’s ability to adjust and recover. Based on mobile payments, smart contracts and other technological tools, digital inclusive finance significantly reduces the time it takes to obtain financing and pay off insurance and lowers the decision threshold for farmers to adopt the technology. This allows them to dynamically optimise the reallocation of resources during key operational cycles (e.g. planting windows and peak disaster relief periods) and improves the food industry’s ability to adapt and recover despite external shocks. Third, digital financial inclusion can use big data models to study the direction of market trends and help the industry better respond to market changes and technological challenges, providing strong support for the sustainable development of the food industry. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 4 as follows:

H4: Digital financial inclusion plays a positive moderating role in the positive impact of technological innovation in food production on food industry resilience.

The impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry has spatial spillover effects based on the endogeneity of market size constraints and the exogeneity of communication and transportation development. Market size constraints are intrinsic motivation for the spatial spillover effect of technological innovation on the enhancement of food industry resilience. Because of the constraints of the market size of the service object, food production service industry enterprises cannot provide localised services and usually seek more distant services, thus generating a spatial spillover effect. The development of communication technology and transportation infrastructure is the external driving force behind the spatial spillover effects of technological innovation on food industry resilience. The development of communication technology and transportation infrastructure enables more frequent exchanges of factors such as talent, knowledge, technology and information, thus reducing costs and increasing the frequency of exchanges. Technological innovation can not only provide productive services for the development of the local food industry and improve its productivity but can also enhance the productivity of the neighbouring food industry through spatial spillover effects. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 5 as follows:

H5: The impact of technological innovations in food production on the resilience of the food industry has spatial spillover effects.

Methodology and research designData sourcesThe original provincial panel data used in this study were obtained from China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, the website of the National Bureau of Statistics, China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook, and the statistical yearbooks of each province between 2003 and 2022. This study also used the Peking University Inclusive Finance Index (2011–2022) released by the Digital Finance Research Center at Peking University to reflect the development level of inclusive finance in each province during the study period. Data used in this study were all published by official statistical agencies, which are highly authoritative and reliable. Given the availability and completeness of the data, this study identified the study population as 31 provinces in China, excluding Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan. This study used standardised data processing methods, including data cleaning, data integration and data validation, to ensure data accuracy and consistency. Furthermore, we used a linear interpolation method to handle missing data to ensure data integrity.

ModellingEntropy methodTo reduce the bias in the indicator measurement, this study uses the relatively objective and scientific entropy value method to make an objective assignment. The entropy value method is used to determine weights through a combination of mathematical and computer simulations by assessing the degree of dispersion of the indicators. The greater the degree of dispersion of the entropy value, the greater the impact of the indicator on the comprehensive evaluation. Therefore, according to the degree of variability of the indicators, the information entropy can be used as a tool to calculate the weight of each indicator, providing a basis for the comprehensive evaluation of multiple indicators. The specific steps of the entropy method are as follows:

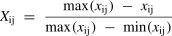

(1) Standardise indicators. To exclude the influence of different data’s quantitative outlines on the evaluation results, the data of the selected indicators were made dimensionless, and the raw data were standardised.

Positive indicators:

Negative indicators:

where Xij represents the standardised data for indicatorj for year i, xij represents the raw data for indicator j for yeari, max(xij) is the maximum value for indicator j for all years and min(xij) is the minimum value for indicator j for all years.(2) Determine the entropy value of thejth indicator using the following equation:

where Sj denotes the entropy value of the jth indicator,Yij denotes the weight of the jth sample and n is the number of evaluation samples.(3) Determine indicator weights using the following equation:

whereWj represents the weight of indicator j and m denotes the number of indicators.(4) Calculate the composite index. After obtaining the weights of the jth indicator, the score of the jth indicator in the ith year can be calculated as follows: Yij=WjXij. The composite index for each year is calculated using the following linear weighting method: Yi=∑j=1mYij. The value of the composite index Yi ranges from 0 to 1, with a higher value of Yi indicating a more resilient food industry.

Ordinary least square modelTo verify the hypothesis concerning the impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry, this study constructs a panel ordinary least squares (OLS) regression model as follows:

where Yit denotes the regional food industry resilience index, Xi,t denotes the food science and technology innovation, i is the province (district), t is the year, Controli,t is a series of control variables and a and εi,t denote the constant and random disturbance terms, respectively.Mechanism verification modelsTo further examine the pathways through which technological innovation in grain production affects the resilience of the grain industry, this study follows the approach of Jiang (2022) and employs a two-step method to test the mediating effect of the mechanism variables. Based on Eq. (5), the following regression model is constructed:

where Z represents the mediating variables in this study, which include employment structure and grain import dependence. The meanings of the other symbols are consistent with the previous text, and this study mainly estimates the coefficients b′.Furthermore, to verify the moderating role of inclusive finance in the impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry, the following moderating effect model is constructed:

where M represents the mediating variable of inclusive finance. The definitions of the other symbols are consistent with the previous text. β is the coefficient of the interaction term between X and M. If β is significant, then M has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between X and Y.Spatial Durbin modelGiven the spatial relevance of technological innovation, food industry resilience and other factors that flow between provinces, this study constructs the following spatial Durbin model to test the spatial impact of technological innovation on food industry resilience:

whereρ is the spatial autoregressive coefficient, which indicates the impact of the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces on that province. Wij is the spatial weight matrix, describing the spatial characteristics of each province. φ1 and φ2 are the spatial interaction coefficients.This study further employs the partial differential estimation method of the spatial regression model to decompose the spatial effect into direct, indirect and total effects. The specific process is as follows:

where In is a unit matrix of order n, ln is the order of the n×1 matrix, k denotes the number of independent variables in the equation, β1m denotes the regression coefficient of the mth variable in the independent variable X and β2m denotes the regression coefficient of the mth variable in WX. To analyse the role of Hr(W) in the econometric model, this study extends Eq. (11) from one region to n regions, whose corresponding matrices take the following forms:The mth variable in Eq. (15) in the explanatory variables for the other regions is deflected and deformed to obtain Eq. (16), and the mth variable in the explanatory variables within the region is deflected to obtain Eq. (17):

In Eq. (16), Hm(W)ij denotes the effect of the mth independent variable in region j on the dependent variable in region i, i.e. the indirect (spillover) effect. In Eq. (17), Hm(W)ii denotes the effect of the mth independent variable of region i on the explanatory variables of the region, i.e. the direct effect. The total effect is the sum of the direct and indirect effects. In this study, the direct effect refers to the impact of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry in a specific province, whereas the indirect effect represents the spatial effect of local technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry in other provinces.

Selection of variablesExplanatory variable: resilience of the food industryBased on China’s reality, this study defines the resilience of the food industry from the perspective of food security as the ability of the food system to withstand external shocks, recover quickly from shocks and achieve adaptive development by shifting to a new growth path. Referring to Hao and Tan (2023), Zhao et al. (2023) and Zuo and Ye (2024), this study constructs an economic resilience evaluation index system from risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability, as shown in Table 1. Risk resistance refers to the ability of the food industry to reduce losses under external shocks, adjustment and recovery refers to the self-adjustment and recovery ability of the food industry after encountering a crisis and sustainability refers to the green production and sustainable development ability of the food industry.

Food industry resilience indicator system.

With reference to the study by Jiang and Zhou (2022), this study uses the number of food patents granted as a measure of technological innovation, which is logarithmically processed to eliminate the effect of heteroskedasticity.

Mechanism variablesThis study examines two categories of mechanism variables. The first category includes the mediating variables, which include employment structure and food import dependence. The employment structure refers to the proportion of high-skilled labour force (Hsl), whereas food import dependence (Gid) is calculated using the ratio of grain imports to total food production. the second category includes the moderating variable. In this study, digital inclusive finance is selected as the mediating variable, which includes three indicators: the level of digital inclusive finance (Dfi), payment services (Pay) and credit services (Credit). The level of digital inclusive finance is represented by the total index of digital inclusive finance. Payment services are primarily assessed based on the actual usage frequency of these services by users, whereas credit services are evaluated based on the actual usage frequency of these services by users.

Control variablesTo ensure the accuracy of the regression results, considering that the resilience of the food industry is also affected by other factors, referring to the existing literature, this study uses five variables as control variables: economic level (lngdp), urbanisation rate (urban), level of human capital (firm), rural electricity consumption per capita (elec) and rural road network accessibility (road). The detailed definitions are given in Table 2.

List of variable definitions.

This study empirically examined the impact of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry using an OLS fixed-effects model. Table 3 presents the regression results of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry and its different dimensions without considering spatial effects. Column (1) presents the regression results of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry. Technological innovation has a significant positive impact on the resilience of the food industry at the 1 % statistical level, indicating that technological innovation in food production has a positive effect on the resilience of the food industry. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 of this study can be verified. Columns (2) to (4) show the results of the regression of technological innovation on the risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability of the food industry, respectively. The results show that the coefficients of technological innovation are all positive and statistically significant at the 1 % level, demonstrating that technological innovation in food production has a positive impact on the risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability of the food industry. Hypotheses 1a–1c have been verified.

Regression results of the OLS model.

Note: Values in parentheses are standard errors, and ***, **, and * denote P < 0.01, P < 0.05, and P < 0.1, respectively, below.

The research findings suggest that technological innovation can enhance the resilience and recovery of food production systems, making them more robust against external shocks, such as natural disasters and market fluctuations. For instance, the advancement of agricultural mechanisation can improve the efficiency and stability of food production, reducing reliance on external labour and strengthening the resilience of food production systems. Technological innovation also directly reduces the use of inputs, thereby lowering the marginal costs of agricultural production. In addition, agricultural technological innovation promotes the use of environmentally friendly technologies (e.g. soil testing and formulation technology and smart irrigation systems) that not only reduce the use of pesticides and chemical fertilisers but also improve the efficiency of water use, thereby reducing the negative impact on the environment and increasing the sustainability of food production.

To further validate the long-term effects of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry, this study proposed a staged tracking plan with data updates every 5 years to comprehensively analyse the dynamic effects of technological innovation. The sample was divided into four 5-year periods, and regression analyses were conducted for each period. The results are presented in Table 4. In Period 1 (2003–2007), the coefficient of the variable Innovate was 0.0003 and significant at the 5 % level, indicating a significant positive effect of technological innovation on food industry resilience. In Period 2 (2008–2012), the coefficient of Innovate increased to 0.0004 and was significant at the 1 % level, suggesting that the positive impact of technological innovation on food industry resilience further strengthened during this period. In Period 3 (2013–2017), the coefficient of Innovate decreased to 0.0001 and was significant at the 10 % level, indicating a weakening of the positive effect of technological innovation on food industry resilience. In Period 4 (2018–2022), the coefficient of Innovate failed to pass the significance test, suggesting that the impact of technological innovation on food industry resilience was no longer statistically significant during this stage. The results demonstrate that the long-term effects of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry exhibit distinct stage characteristics. The impact is stronger in the early stages but diminishes over time because of the maturation of technology adoption and changes in external environments. Eventually, the marginal effects may become insignificant, indicating that the long-term effects of technological innovation may have certain limitations.

Different stages of regression results.

This study used three main approaches to robustness testing. Table 5 presents the robustness results. Column (1) presents the regression results after bilateral trimming of variables at a 1 % significance level. Technological innovation still has a significant positive impact on the resilience of the food industry, which is consistent with the benchmark regression results. Furthermore, the extreme event of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in late 2019 and early 2020 may have resulted in significant differences in the data for that year compared with other years, thus distorting the overall trend. To avoid distortions due to sample selection bias, the 2020 sample was excluded from this study for robustness testing. The results are presented in Column (2). Technological innovation still has a significant positive impact on the resilience of the food industry. Moreover, to address potential model selection bias, this study employed a panel Tobit model for robustness testing. Column (3) presents the results of the Tobit model, in which the positive effect of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry passed the significance test, again confirming the robustness of the estimates.

The results of the robustness test.

Although we controlled for factors that may affect technological innovation and food industry resilience, the empirical results may still be affected by some unobservable factors. Such omitted-variable bias could lead to biased coefficient estimates in our analysis. Furthermore, a reverse causality concern may exist because enhanced resilience in the grain industry inherently generates greater demand for technological innovation. To alleviate the endogeneity problem caused by omitted variables, measurement error or reverse causality, this study used the instrumental variable (IV) approach and selected local fiscal expenditure on science and technology as the instrumental variable. This policy-driven instrument satisfies the relevance condition through its direct impact on agricultural technology R&D and diffusion, thereby exhibiting a strong correlation with grain production innovation. Concurrently, it meets the exclusion restriction because local fiscal allocations for scientific expenditures are primarily determined by government budgetary planning mechanisms that remain exogenous to the micro-level dynamics of grain-industry resilience. As presented in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 6, the IV estimation results demonstrate statistical validity. The first-stage regression revealed that the instrumental variable significantly predicts endogenous technological innovation at the 1 % confidence level, with an F-statistic of 33.12, which exceeds the critical threshold of 10, thereby eliminating concerns about weak instruments. The Hansen J statistic was 2.594, with a p-value of 0.1073, which exceeds the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, we did not reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the selected instrumental variables are valid. The second-stage results confirm the absence of severe endogeneity through a Wald test (Prob > chi2 = 0) while maintaining a statistically significant positive correlation (at the 1 % level) between technological innovation and food industry resilience. These findings robustly corroborate our primary research conclusions.

The results of the endogeneity test.

Note: The values in parentheses are robust standard errors.

In addition, this study incorporated the one-period lag of technological innovation into the benchmark regression model to examine the lagged effect of previous technological innovation on the current resilience of the food industry. Moreover, the current food industry’s resilience is unlikely to impact the technological innovation of the previous period; therefore, this approach also mitigates the endogeneity problem due to reverse causality. As shown in Column (3), both the coefficients of Innovate and L. Innovate were significantly positive at the 1 % level, indicating a significant positive impact of previous technological innovation on the current food industry’s resilience. Thus, technological innovation has a lagged and long-term effect on food industry resilience.

Mechanism testing of the impact of technological innovation on food industry resilienceMediating effect test resultsThe aforementioned research confirms that technological innovation in grain production can significantly enhance the resilience of the food industry. Building on the theoretical analysis in the previous sections and drawing on the mechanism testing approach by Jiang (2022), this study examined the mediating effects of employment structure and food import dependence to verify Hypotheses 2 and 3. To address potential endogeneity issues arising from reverse causality, this study employed an IV approach, using local government expenditure on science and technology as the instrument. The regression results are presented in Table 7. Column (1) displays the second-stage regression results, with the proportion of high-skilled labour as the mediating variable. The regression coefficient of technological innovation in food production on the proportion of high-skilled labour was positive and statistically significant at the 5 % level. Column (2) presents the regression results after controlling for regional human capital stock, as in Column (1). The regression coefficient of agricultural technological innovation on the share of highly skilled labour was positive and significant at the 1 % level. These findings indicate that after mitigating potential endogeneity and further controlling for regional human capital stock, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed. These results indicate that technological innovations in food production have altered employment structures. They have created new jobs and increased the demand for high-skilled positions.

The results of the mediating effect.

Note: The values in parentheses are robust standard errors.

However, it is difficult to capture the heterogeneous responses of small- and medium-sized farmers and large enterprises using provincial panel data. To supplement the limitations of the macro-analysis, we analysed the cases of a large-scale agricultural reclamation enterprise (Hongxinglong branch of the Beidahuang Group) and a small-farmer agglomeration (Dezhou’s agricultural technology service centres) to deconstruct the differential transmission paths of employment structure in the impact of technological innovations on the resilience of the food industry.

Beidahuang Group is the largest japonica rice production base in China, with its Hongxinglong branch boasting more than 8 million mu of arable land. Agricultural technology innovation has become a good tradition for the Hongxinglong branch. For example, the Hongqiling Farm, which is under the jurisdiction of the Hongxinglong branch, implemented a project to popularise intelligent agricultural machinery, achieving unmanned operation and intelligent irrigation in 3300 mu of paddy fields. Youyi Farm uses satellite navigation for unmanned rice planting and satellite remote sensing to spray fertiliser precisely. In recent years, the Hongxinglong branch has cultivated several local agrotechnical experts and established a high-level scientific research cooperation platform that leverages the advantages of technological innovation and application. This has significantly enhanced an enterprise’s human capital. For example, Youyi Farm has attracted high-quality research resources from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences and China Agricultural University, as well as other research institutes. It has participated in nearly 100 major research projects and has declared 23 patents. Furthermore, it has established a pool of 225 farm talent echelons and 118 outstanding reserve talents, providing robust scientific, technological and talent support for development. Stable and high-grain production in this branch is now the result of strong innovation dynamics and continuous optimisation of human capital. By the end of 2022, the contribution of agricultural science and technology to the Hongxinglong branch reached 78 %, with an annual increase in grain production capacity of 5 %. This phenomenon of labour replacement due to technological progress echoes the improved employment structure revealed by provincial panel data.

Such pathways have also been demonstrated in the case of smallholder farmers. Dezhou is a key area for the rotation of wheat and corn in China, characterised by significant land fragmentation. To address the challenges of adopting mechanisation technology, the Dezhou government and agricultural organisations have established agricultural technology service centres. These centres provide various services, including agricultural supply, soil testing and fertilisation, machinery operation and production trusteeship. As of 2024, a total of 72 service centres have been established in Dezhou to provide agricultural hosting services to villagers. The adoption of agricultural technology and the implementation of agricultural hosting have contributed to the optimisation of human capital. First, Dezhou’s agricultural technology service centres have employed agricultural experts to provide technical guidance. Second, Dezhou’s agricultural technology service centres have innovatively established farmland administration roles, with each administrator managing between 300 and 500 acres of land. This measure promotes efficient management of farmland and cultivates agricultural talent. Third, Dezhou’s agricultural technology service centres have established a professional farmer partnership model. This forms a stable, profit-sharing mechanism between farmers, village collectives and supply and marketing cooperatives. It also guarantees sustained benefits for farmers and village collectives. The effective integration of inter-regional resources for agricultural socialisation services through the innovation and adoption of technology enhances local human capital and employment structure, thus improving the resilience of the agricultural industry. In 2023, agricultural technology service centres in Texas reduced the use of fertiliser and pesticides by more than 20 %. They saved 3.32 million yuan through reduced water, electricity and fertiliser use; increased grain production by 4.26 million pounds; and helped farmers increase their incomes by 8.17 million yuan.

These cases confirm that the transmission logic of technology-induced structural optimisation of employment at the micro-organisational level is consistent with the macro-impact mechanism. However, large enterprises are more capable of accelerating the structural transformation of the labour force by virtue of their capital accumulation advantages (e.g. up-front investment capacity for the acquisition of smart agricultural machinery) and technology transformation capacity (e.g. school–enterprise cooperation in the cultivation of proprietary skilled personnel). Smallholder farmers rely on external social service resources (e.g. agricultural hosting) and benefit linkage mechanisms to optimise human capital. The above cases provide a micro-level evidence base for understanding heterogeneity in response to technology shocks of different business entities.

Column (3) presents the regression results with food import dependence as the mediating variable. The coefficient of technological innovation in food production was positive but not significant, indicating that technological innovation in food production does not have a significant impact on food import dependence. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is rejected. This result may be due to a variety of reasons. First, the main objective of technological innovation in food production is to improve domestic production efficiency and quality, and its impact on import dependence may not be direct. For example, technological innovation may increase short-term production costs (e.g. equipment investment), leading to an increase in food prices, which may, in turn, increase the demand for low-priced imported food. Second, the effects of technological innovation in food production often have a lag and may not significantly reduce import dependence in the short term. In addition, technological innovation may mainly affect the production efficiency of certain specific food crops, and its impact on import dependence may vary depending on the structure of imported food.

Moderating effect test resultsTable 8 presents the results of the moderating effect test. Column (1) displays the regression results for the level of digital inclusive finance as the moderating variable. The coefficient of the level of digital inclusive finance was significantly positive at the 1 % statistical level, and the coefficient of the interaction term between the level of digital inclusive finance and technological innovation in food production was also significantly positive at the 1 % level. This indicates that the level of digital inclusive finance has a positive moderating effect on the positive impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. This suggests that the level of digital inclusive finance can enhance the promoting effect of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry. Hypothesis 4 is confirmed.

The results of the moderating effect of digital inclusive finance.

Columns (2) and (3) present the regression results with payment services and credit services as moderating variables, respectively. The coefficients of the interaction terms between payment/credit services and agricultural technological innovation were both statistically significant and positive at the 1 % level. This indicates that the payment and credit services of digital inclusive finance can enhance the positive effect of technological innovation on agricultural resilience. These results suggest that the positive moderating role of digital inclusive finance is primarily reflected in the following two aspects. First, digital inclusive finance effectively reduces financing costs and provides accessible financing channels for market entities, thereby alleviating financial constraints during the initial stages of technology adoption. Concurrently, it enhances credit accessibility, enabling more high-potential enterprises to obtain financial support, which in turn promotes innovation and enterprise development. Second, digital inclusive finance accelerates the diffusion of agricultural technologies through socialised networks, facilitating real-time sharing of production information and the widespread adoption of mobile payments. This mechanism reduces transaction costs, improves resource utilisation efficiency and strengthens the risk resilience of the food industry chain.

The Peking University Inclusive Finance Index categorises China’s 31 provinces into three tiers (ranked from high to low), revealing significant regional disparities in digital inclusive finance development. Our empirical analysis further investigates the differential moderating effects of digital inclusive finance across tiers. Column (4) presents the regression results for Tier 1 provinces, where the moderating effects of digital inclusive finance did not meet statistical significance. In contrast, significant moderating effects were observed in Tiers 2 and 3. These results indicate a significant marginal diminishing and structural threshold effect in the regulatory effect of digital inclusive finance. Two main reasons could explain this phenomenon. First, the marginal effect diminishes with development. In Tier 1 provinces (Beijing, Shanghai and Zhejiang), digital finance penetration is high, deeply integrated into the regional economy, reducing its marginal boost to technological innovation. In contrast, in Tier 2 and 3 provinces, digital finance is at a stage of increasing returns, with each unit of index growth significantly enhancing technological empowerment. Second, there are differences in the substitution effects of market structures. In more developed regions, traditional financial institutions and digital platforms compete with one another, weakening digital finance’s incremental regulatory effect. In contrast, in less developed regions, where traditional financial supply is insufficient, digital finance offers a structural supplement through long-tail coverage.

Spatial measurement estimation resultsThis study employed the spatial Durbin model (SDM), which uses the bias-corrected quasi-maximum likelihood estimator (QMLE) proposed by Lee and Yu (2010) to estimate spatiotemporal double fixed-effects. Table 9 presents the estimation results of the SDM model with double fixed effects in time and space using the geographic–distance spatial weight matrix and the economic–geographic nested weight matrix. Innovate were all significantly positive at the 1 % statistical level, indicating that technological innovation has a significant positive effect on the resilience of the food industry, which once again validates Hypothesis 1. The spatial autoregressive coefficients in the SDM model ρ were all positive and significant at the 1 % statistical level, indicating that the explanatory variable, the resilience of the food industry, has a significant positive spatial spillover effect on itself. In addition, the values of the coefficients ρ under the economic–geographic nested weight matrix were smaller than those under the geographic–distance spatial weight matrix, suggesting that spatial correlation is mainly affected by distance. The coefficients of WxInnovate were all significantly negative at the 1 % statistical level, suggesting that technological innovations have a negative spatial spillover effect, limiting the improvement of the resilience of the food industry in the neighbouring provinces, which is contrary to Hypothesis 5. Further validation is needed.

Regression results of the spatial measurement model.

Lesage and Pace (2008) noted that testing intra-regional and spatial spillover effects should further focus on whether the direct and indirect effects of explanatory variables are significant. Therefore, this study conducted a partial differential decomposition of the regression results to obtain the direct and indirect effects of technological innovation, and the results are shown in Table 10. Under the geographic–distance spatial weight matrix and economic–geographic nested weight matrix, the direct effect of Innovate was significantly positive, indicating that technological innovation can improve the resilience of the food industry in the region. However, the indirect effect of Innovate was significantly negative, which is consistent with the previous regression results and rejects Hypothesis 5. The results indicate that technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces shows an obvious siphon effect. In particular, provinces with a high level of technological innovation can attract labour, financial resources and market share from neighbouring provinces. This leads to an uneven distribution of labour and financial resources, which exacerbates the regional development gap and hinders the strengthening of the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring regions through technological innovation.

Direct and indirect impacts of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry.

To further explore the characteristics of the impact of technological innovation on the resilience of the food industry within different regions, this study divided the sample into eastern, north-eastern, central and western regions according to the division criteria established by the National Bureau of Statistics. The results are shown in Table 11. The coefficients of technological innovation were all significantly positive at the 1 % statistical level, indicating that technological innovation has a significant positive effect on the resilience of the food industry across different provinces in various regions. The coefficient of WxInnovate was significantly negative in the eastern, central and western regions and was significantly positive in the north-eastern region. These results indicate that technological innovation has a significant siphoning effect on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces in the eastern, central and western regions and a significant spillover effect on the resilience of the food industry in the north-eastern region. Possible reasons for these effects include the following. Because of its developed economy and rich scientific and technological resources, the eastern region is often able to attract and gather a large number of high-end talents, advanced technologies, capital and other innovation factors. This has enabled the region to take the lead in technological innovation in the food industry, significantly improving its production efficiency, product quality and market competitiveness, thereby attracting more resources and market share and creating a siphon effect on neighbouring provinces. The western region, with its underdeveloped economy and relatively scarce scientific and technological resources, often faces greater difficulties in technological innovation in its food industry, which may be more dependent on external technical support and resource inputs. When external resources are concentrated in one province, the lack of regional collaboration among provinces may have a dampening effect on the resilience of the food industry in other provinces around that province. The central region, as the interface between the eastern and western parts of the country, is often able to receive industrial transfers and technological spillovers from the eastern part of the country. However, its economic development and technological innovation ability are relatively weak, and its resources and markets are relatively limited. Therefore, its food industry is often in a state of catching up in terms of technological innovation, thus demonstrating a siphon effect on neighbouring provinces.

Spatial econometric regression results of technological innovation on food industry resilience in different regions.

The technological innovation spillover effect in Northeast China’s grain industry mainly stems from two factors: geographical proximity and industrial complementarity. First, geographical proximity facilitates the formation of a technology diffusion network. The tri-provincial region encompassing Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang exhibits homogeneous agroecological conditions and an integrated transportation infrastructure, forming a technology diffusion network. This compact geographical configuration significantly reduces spatial transaction costs for knowledge transfer, facilitating cross-regional mobility of technical expertise, intellectual capital and human resources. The resultant spatial externality enhances the permeability of innovation diffusion across administrative boundaries. Second, industrial complementarity allows for the mutual supplementation of grain production. The three provinces demonstrate strategic complementarities across multiple dimensions of grain production systems. Divergent cropping structures and cultivation techniques among jurisdictions enable an optimised allocation of agricultural resources and collective yield enhancement. In processing and logistics, Heilongjiang’s grain logistics experience, Jilin’s modern warehousing technology and Liaoning’s port logistics advantage form an efficient logistics system. This complementarity enables resource sharing and advantage complementarity in all grain-industry links, driving technological-level upgrading and creating a spillover effect where innovation in one industry boosts related industries. This dual mechanism of spatial agglomeration economies and industrial complementarities establishes a self-reinforcing cycle of technological upgrading and knowledge externalities within the regional innovation system.

Discussion and conclusionsBased on the provincial panel data of 31 provinces in China from 2003 to 2022, this study constructed an evaluation system for the resilience of the food industry. We used OLS to empirically analyse the impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. Furthermore, we applied SDM with spatiotemporal double fixed effects to investigate the potential spatial spillover effects of technological innovation in food production on industry resilience. Five conclusions have been drawn. First, technological innovation in food production has a positive influence on the resilience of the food industry, as well as on its risk resistance, adjustment and recovery and sustainability, which is consistent with the findings of recent studies (Sarfraz et al., 2023; Shi et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2023). Furthermore, technological innovation exerts a long-term effect on the resilience of the food industry. However, this impact exhibits a distinctly diminishing marginal character. Second, technological innovations in food production increase the resilience of the food industry by optimising the employment structure and facilitating the transition of food industry employment demand from low-skilled to high-skilled positions. Third, digital inclusive finance and its associated credit and payment services can enhance the positive impact of technological innovation in food production on the resilience of the food industry. Notably, digital inclusive finance is characterised by significant gradient differences and diminishing margins. Fourth, technological innovation has a significant siphoning effect on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces, which is contrary to the findings of Zhang and Song (2022) but aligns with those of Barata (2019) and Karacay (2018). Provinces with a high level of technological innovation can attract human and financial resources and market share from neighbouring provinces. This limits the ability of the food industry in neighbouring regions to enhance its technological innovation, thus intensifying the regional development gap. Fifth, the analyses of heterogeneity indicate that technological innovation has a significant siphoning effect on the resilience of the food industry in neighbouring provinces in the eastern, central and western regions. Meanwhile, a significant spillover effect is evident in the north-eastern region.

Based on the above findings, the following policy recommendations are put forward.

First, the role of technological innovation in enhancing food industry resilience should be given high priority. Policies should increase support for technological innovation in the food industry and strengthen research on good seeds and the promotion of agricultural technology. Policies should also encourage the exchange of food technology between firms and countries, promote the integration of innovative resources and enhance absorption and transformation capabilities. Furthermore, given that the long-term effects of this impact diminish marginally, a differentiated support system covering the entire technology diffusion cycle should be established. In the early stages of technology adoption, policies should promote technology and reduce adoption barriers through measures such as subsidies, training and insurance, as well as the establishment of agrotechnology extension stations. At the medium stage, policies should focus on improving the efficiency of technology applications. For example, socialisation services for agricultural technologies could be established. In the later stages, policies should encourage the replacement of technology through mandatory measures, the elimination of subsidies, research support and other initiatives.

Second, it is necessary to optimise the employment structure of the food industry. Policies should use modern agricultural industrial technology systems to establish digital agricultural training centres in major grain-producing counties, focusing on cultivating highly skilled personnel in areas such as the operation and maintenance of intelligent agricultural machinery and the Internet of Things in agriculture. In addition, differentiated subsidy policies should be developed to create market-based incentives to optimise the employment structure. For example, agricultural businesses that employ a high proportion of highly skilled labour should receive a rent reduction or exemption for transferred land, as well as a premium for agricultural machinery purchase subsidies.

Third, digital inclusive finance should be accurately regulated based on gradient characteristics. Policies should optimise inclusive financial services and improve credit approval and risk management. This will enhance the accessibility and quality of financial services for food enterprises, individual businesses and farmers. Furthermore, policies should reinforce the role of inclusive finance in promoting technological innovation in food production. For example, governments and banks can develop dynamic assessment systems for technology adoption and provide special low-interest loans to business entities that actively adopt risk-resistant technologies, such as water-saving irrigation and vertical farming. However, this study revealed a significant gradient effect on the moderation of digital inclusive finance. Policies must address the marginal efficiency loss caused by the current one-size-fits-all policy for digital inclusive finance, which can be achieved by establishing differentiated tools on a gradient basis. For example, in first-tier provinces, untechnologically linked inclusive loans should be issued less frequently and supply-side structural reforms in fintech should be deepened. In second- and third-tier provinces, promoting rural digital infrastructure and developing digital financial service systems for villages are essential. In addition, exploring methods to create synergies between technology and finance is crucial. One approach is to dynamically link credit lines to technology adoption.

Fourth, regional synergistic mechanisms for technology should be developed to reduce inter-regional differences in food system resilience. The food industry’s resilience has a significant positive spatial correlation. Technological restrictions and protectionism should be eliminated between provinces and cities, and a mechanism for compensating for technological factors across regions should be established. Policies can encourage regions with resilient food industries to increase the resilience of neighbouring food systems by establishing inter-provincial technology transfer funds, providing foreign technological assistance and cooperating on projects. Regions with low levels of resilience can strengthen their cooperation with more resilient provinces and learn from their advanced practices and experiences. For example, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) strategic programme has established dedicated funds that can be used for environmental, climatic and ecological objectives, as well as to reduce regional imbalances in agricultural development and farm operations. China can refer to the experience of CAP in setting up a cross-regional technology transfer fund and implementing project cooperation and technology exchanges under the framework of East–West twinning. Furthermore, it is crucial to establish an information platform for agricultural technology to enable the exchange of factors and market linkages. For example, Guizhou Aerospace Intelligent Agriculture Co. Ltd. has independently developed a wireless intelligent irrigation system that enables agricultural cultivation to save more than 30 % of human and water resources. The company has implemented more than 220 smart agriculture projects in more than 20 provinces of China, enabling the sharing of information technology resources.

Fifth, differentiated regional strategies for technology diffusion should be developed to balance siphoning and spillover effects. To prevent resource over-concentration, the eastern region should implement technology dividend feedback policies, such as setting up inter-provincial technology transfer funds and establishing inter-provincial supply chains. The region can leverage its technological innovation strengths to promote synergistic development in other provinces by providing technical guidance and collaborating on projects. Technologically backward provinces in the central and western regions should prioritise the optimisation of agricultural equipment and the adoption of agricultural technologies in mountainous regions. One way to achieve this would be to apply differentiated agricultural subsidy rates according to altitude gradients. In addition, the central region should accelerate the construction of a modern grain logistics centre to improve food security. The north-eastern region should seek to strengthen the spillover effects of technological innovation and encourage the sharing of such technology. Leading enterprises in the grain industry in the north-eastern region could be encouraged to provide technical guidance to other provinces. For example, the Beidahuang Group’s green unmanned rice and wheat cultivation technology has been listed as a leading technology by the Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs and promoted in the country’s main rice and wheat production areas.