This study examines the impact of a commitment to Sustainable Development Goal 9 (SDG 9) objectives by exploring sectoral and regional disparities in how companies aligned with this goal leverage digital technologies and knowledge, foster innovation ecosystems, and deliver measurable contributions to sustainable infrastructure development. Using the SDG-aligned revenue share as the main metric for SDGs commitment across 5,323 global companies provided by the Upright platform, we employed a machine-learning-based k-means clustering algorithm to detect patterns of net impacts created across the Society, Knowledge, Health, and Environment (SKHE) dimensions. We also uncovered sectoral and geographical patterns of the companies investigated. Our findings show that alignment with SDG 9 (Industry, Knowledge, and Innovation) is associated with corporate commitment to SKHE dimensions, as well as sectoral and, to some extent, geographical scope. The results offer practical implications for investors, policymakers designing regulations and guidelines to improve sustainability disclosure, and company executives who are developing sustainability strategies.

The adoption of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 marked a significant milestone toward global sustainability. A set of 17 global objectives, broken down into 169 specific targets, was released as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (Desai et al., 2018; Soltau, 2021; Srivastava, 2022). These targets aim to foster sustainable development and growth while addressing a wide range of global challenges around the three pillars of sustainability: economic sustainability, social sustainability, and environmental sustainability (Ferrari et al., 2024; Parotto & Pablos-Méndez, 2023).

Sustainable Development Goal 9 (SDG 9), which promotes resilient infrastructure, sustainable industrialization, and innovation, has gained significant attention in corporate sustainability strategies and reporting. This is driven by the recognition that private sector alignment is vital for achieving long-term sustainability in global infrastructure and innovation development (Leonavičienė et al., 2024). SDG 9 encompasses a set of eight targets focusing on infrastructure development, industrialization, financial access for enterprises, sustainable industry upgrading, scientific research enhancement, and universal Information and Communication Technology (ICT) access (Desai et al., 2018; UNDP, 2024). Although assessing this objective is challenging, it is one of the most widely discussed SDGs in the academic literature alongside SDG 3 and SDG 6, which focus on good health, clean water, and sanitation together with affordable and clean energy (Philip et al., 2024; Schmutzhard & Pfausler, 2021; Meier, 2023).

Despite the extensive coverage of SDG 9, the existing literature has several limitations that prevent a comprehensive understanding of corporate engagement in this area. First, the multidimensional nature of infrastructure, innovation, and industrialization requires sophisticated measurement frameworks that capture both quantitative and qualitative aspects of corporate contributions (Arjaliès & Mundy, 2013). Data availability and consistent indicators are often cited as challenges in measuring SDG 9 alignment; manufacturing companies typically have more direct metrics for industrialization targets, whereas service sectors struggle with quantifying their infrastructure contributions (Di Tommaso et al., 2017; Huang & Badurdeen, 2018). Similarly, technology companies benefit from the availability of digital metrics but face challenges in demonstrating the impact of global development (Rosamartina et al., 2022; Stephenson, 2021).

Although a stronger commitment to SDG 9 enhances innovation capacity while promoting sustainable practices (Cabaleiro-Cerviño & Mendi, 2024; Hambali, 2024; Nechita et al., 2020), improved coordination and deeper integration are required for meaningful progress. Schramade (2017) found that companies demonstrating authentic commitment typically select fewer targets but provide more comprehensive reporting and measurement, while an earlier study conducted by Khan et al. (2016) suggests that companies focusing on material sustainability issues perform better financially and have improved levels of stakeholder engagement. Nevertheless, a genuine commitment to SDG 9, especially when paired with innovation and robust sustainability strategies, is associated with improved corporate sustainability and performance; moreover, this impact is maximized when such commitments are substantive, well-reported, and supported by strong leadership and favorable organizational contexts (Khalad, 2021; Rahman et al., 2023; Rosamartina et al., 2022).

Second, prior research on SDG 9 has predominantly focused on policy analysis, disclosure practices, or single-sector case studies, leaving a significant gap in data-enhanced explorations of how companies align their business models with SDG 9 targets (Sachs et al., 2022; Van Der Waal & Thijssens, 2020). Moreover, given that much of the existing empirical evidence relies on secondary reporting sources (McGill, 2018), there are concerns about potential greenwashing practices and our understanding of the actual sustainability impact of corporate operations remains limited.

At the same time, it is evident that companies are increasingly adopting and reporting on SDG 9 practices due to a combination of internal organizational factors, external pressures, and strategic motivations. Key driving factors include company size, commitment to sustainability frameworks, board characteristics, economic performance, and the pursuit of legitimacy and stakeholder trust, in addition to regulatory requirements and investor pressure to improve ESG performance (Rosati & Faria, 2019; Hambali, 2024). Internal factors such as board characteristics and composition, sustainability-dedicated governance, and executive compensation schemes linked to SDG metrics have also been shown to influence corporate engagement regarding SDG 9 (Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2025; Harjoto et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2023; Flammer et al., 2019). However, existing studies have often disregarded sectoral and regional differences in corporate strategies and very few have explored the impact of this heterogeneity on innovation and knowledge creation.

The present study aims to address these limitations and fill an important research gap by examining corporate alignment with SDG 9 using a comprehensive dataset of 5,323 global companies. Our approach is differentiated from prior research in three important ways. First, we examine SDG alignment using revenue-based metrics from the Upright platform, which directly link companies’ products and services to sustainability outcomes rather than relying on self-reported disclosures. Second, departing from traditional regression-based models, we employ a machine learning-based k-means clustering approach to reveal patterns in corporate engagement toward SDG 9. Third, we investigate sectoral and geographical variations in SDG 9 alignment versus misalignment and analyze their relationship with other knowledge and sustainability dimensions.

Our study makes five main contributions to the literature. Firstly, by analyzing a large dataset of 5,323 global companies using a machine learning-based k-means clustering methodology, it moves beyond traditional modelling approaches based on panel regressions with the aim of uncovering complex patterns in corporate alignment with SDG 9. Secondly, from an empirical perspective, the current research addresses sustainability measurement challenges by relying on revenue-based SDG alignment metrics provided by the Upright platform, which connects concrete business activities to sustainability commitment instead of relying on corporate disclosures that may be prone to greenwashing or purpose-washing. Thirdly, from a conceptual and theoretical perspective, the work contributes to understanding heterogeneous patterns in corporate sustainability by demonstrating that firms follow distinct strategic paths to impact the different components of sustainability. Fourthly, by employing a multidimensional impact framework across the Society, Knowledge, Health, and Environment (SKHE) dimensions, this study advances a more nuanced understanding of how corporate adoption of innovation, as reflected in the products and services offered to the market, creates impact and value beyond traditional financial metrics. Finally, the identification of sectoral and geographical patterns in alignment with SDG 9 and sustainability impact provides valuable insights for investors seeking genuine sustainability performance, policymakers designing targeted regulatory frameworks, and corporate managers who are challenged to develop sustainability strategies.

The following section reviews the most important findings advanced in the literature with respect to variations in SDG commitment and reporting across sectors and regions. It also delves into the positive impacts of companies aligned with SDG 9 in terms of both innovation and knowledge creation and financial performance, an area that has gained significant attention from both researchers and practitioners. The third section outlines the research methodology and is followed by a section that presents our findings. The final part of the chapter concludes and indicates directions for future research.

Literature reviewAlthough companies worldwide have aligned their strategies and reporting practices toward SDG integration in recent years, the extent and depth of this alignment vary across sectors and regions (Donkor et al., 2025; Raman et al., 2023). For example, in an exploration of banking sector practices, Scholtens (2017) shows that development banks, rather than traditional commercial banks, pursue more conclusive and consistent SDG 9 alignment strategies in terms of infrastructure financing and innovation funding. Furthermore, recent research by Mirza et al. (2023) and Dou et al. (2025) highlights that sustainable banking funding has a positive impact on the financial performance of banks, coupled with a negative relationship between green lending and default risk. This leads to the conclusion that commitment to both ESG and the SDGs can act as a competitive advantage in the banking sector.

Industry-specific benchmarks, developed to better understand sectoral variations in SDG 9 commitment, show that technology and ICT companies, together with infrastructure and energy companies, particularly those in renewable energy, demonstrate the strongest commitment to SDG 9 through mature integration practices (Kazan et al., 2025). Similar findings have been advanced by Vázquez et al. (2024), who conclude that funds with portfolios diversified among technology and healthcare companies with high Sustainalytics ESG scores display increased profitability and lower risk. In a similar vein, Horobet et al. (2023) reveal that capital market investors evaluate fintech and technology companies based on their ESG performance. Environmental and governance-related initiatives at the corporate level are the most important factors in this process.

These results are unsurprising given that telecommunications companies operate under specific universal service obligations (USOs) that aim to ensure access to essential communication services for all citizens (Garcia Calvo, 2012) and therefore align with Target 9.C; in contrast, manufacturing companies are subject to industrial policy frameworks that influence their innovation and infrastructure reporting approaches (Garcia-Macia & Sollaci, 2024). Numerous studies showcase the manufacturing sector’s commitment to innovation aspects of SDG 9 due to its direct relevance to industrialization and innovation targets. Existing research demonstrates that manufacturing companies achieve SDG 9 targets and create value toward innovation management through industrial efficiency improvements, coupled with technology upgrading initiatives and R&D investment metrics (Setyadi et al., 2025). With respect to the energy sector, an earlier study conducted by Johnstone et al. (2017) indicates a strong commitment to SDG 9 innovation targets among renewable energy companies, primarily as a result of digital transformation and clean technology innovation. Traditional energy companies, in contrast, struggle with transitional alignment. Geels et al. (2017) support this conclusion, with their results suggesting that technical enhancements in energy systems create opportunities for SDG 9 transitional alignment through innovation ecosystem development.

In terms of regional variation, the majority of studies indicate that U.S. companies display strong innovation alignment but weaker infrastructure development commitment compared to their European counterparts (Agyemang et al., 2025; Reid & Toffel, 2009). However, a comprehensive study involving 500 North American companies undertaken by Ioannou and Serafeim (2023) reveals significant cross-border variations, with Canadian companies showing 23 % stronger SDG 9 commitment compared to U.S. companies. This is primarily due to different regulatory frameworks and stakeholder expectations. Asian companies also demonstrate strong variations across subregions, with high levels of commitment to innovation among Japanese companies and Chinese companies showing stronger alignment to SDG 9 targets through infrastructure-related projects (Yang & Rivers, 2009). According to an analysis of SDG commitments among 1,200 Chinese companies by Li et al. (2021), ownership structure plays a major role in SDG 9 commitment; state-owned companies show 89 % higher SDG 9 alignment compared to private companies, mainly due to alignment requirements on government policy.

SDG reporting has developed significantly since the introduction of these goals. The existing literature has advanced several comprehensive standardized frameworks that facilitate greater information sharing at the level of SDG commitments for both countries and organizations (Calabrese et al., 2021; Wernecke et al., 2021; Benedek et al., 2021). Pioneering work on the challenges of integrating SDGs into corporate reporting was undertaken by the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG indicators (IAEG-SDG), which created 231 unique indicators spread across all 169 targets. These indicators were adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission in March 2017. The global indicator framework on social, economic, and environmental issues, which counts for all sustainability pillars, was subsequently adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017 (Kim, 2023). More recently, as companies struggled with mapping business activities to SDG targets due to the lack of sector-specific guidance, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) emerged as the most advanced and widely adopted reporting framework among both academics and practitioners (Urbieta, 2024).

From a corporate perspective, reporting on SDGs is critical in building legitimacy and trust with stakeholders, investors, and the broader public. There has been a surge in sustainability reporting linked to SDG 9 since the creation of the SDGs in 2015, although the depth of integration varies (Li et al., 2018; Al-Qudah & Houcine, 2023). In some regions SDG 9 is one of the most commonly disclosed goals, yet these disclosures often remain superficial and are treated as add-ons rather than integrated strategies (Kazan et al., 2025). The practice of exaggerating innovation practices and engaging in deceptive marketing tactics by amplifying minor SDG 9 commitments rather than pursuing substantive commitments has been described as innovation washing by Xing et al. (2024). Their study shows that, in the Chinese capital market, green innovation has been implemented as a symbolic environmental activity that has failed to lead to innovation efficiency or quality, revealing an accentuated greenwashing behavior (Xing et al., 2024).

Van der Waal and Thijssens (2020) documented this early phase in corporate engagement with SDGs in a longitudinal study, which revealed that only 23 % of Fortune 500 companies made specific commitments to SDG 9 targets during their 2016–2017 reporting cycles. Based on these results, the authors concluded that SDG reporting was mostly symbolic in this time period, focusing on alignment claims rather than substantive integration (Van der Waal & Thijssens, 2020). Furthermore, an earlier study developed by Kolk et al. (2017) concluded that corporations’ initial commitment to SDGs was limited to cherry-picking strategies. Companies selected goals that aligned with existing activities rather than transforming their business patterns. In terms of SDG 9 alignment, incentivized by the positive relationship between sustainability disclosure and firm performance, they emphasized existing R&D activities without necessarily connecting them to broader infrastructure and innovation priorities (Ahsan & Qureshi, 2021).

Moreover, organizations aiming to disclose their alignment with sustainable goals and targets have tended to conclude that traditional accounting practices are insufficient for capturing the complex interdependencies inherent in sustainable development challenges (Bebbington & Unerman, 2018). Moreover, stakeholders and regulators face challenges in addressing greenwashing and ensuring consistency, homogeneity, and comparability of data across different regions and sectors due to large volumes of disclosed information, coupled with the lack of uniform and comparable inputs (Arena et al., 2023; Sopact, 2024). To overcome these shortages, researchers have advocated for the use of Artificial intelligence (AI) systems (Boedijanto & Delina, 2024; Moodaley & Telukdarie, 2023). Machine learning models are enhanced in the context of analyzing CSR reports to identify SDG-related content (Hacihasanoğlu et al., 2024; Rinaldi et al., 2024), while Gunawan et al. (2024) argue that advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques can achieve high predictive accuracy in assessing corporate alignment with SDGs.

Recent trends in sustainability reporting show that leading companies across various sectors are moving toward integrated reporting approaches that combine financial and sustainability metrics, reflecting the recognition that SDG impact assessments will enhance stakeholders’ legitimacy and strengthen their accountability (UN Global Compact, 2024). This evolution is particularly evident in sectors with direct SDG 9 alignment, such as telecommunications and manufacturing, where infrastructure investments directly correlate with both financial performance and sustainability outcomes (Hambali, 2024).

The relationship between innovation investment, sustainability alignment, and financial performance has gained significant attention from both researchers and practitioners, with empirical literature predominantly supporting a positive relationship between SDG 9 alignment and financial performance (Ielasi et al., 2018; Sebastian et al., 2017). Li and Pang (2023) demonstrate that companies aligned with SDG 9 have superior operational efficiency due to systematic approaches to innovation and infrastructure development; moreover; Zhou et al., (2022) explain that ESG-aligned companies employ superior risk diversification strategies, leading to lower capital costs and improved financial stability. According to Mirza et al. (2024), companies with improved scores in the environmental pillar have lower levels of default risk and firms investing in technology projects display superior credit resilience, while Horobet et al. (2025) suggest that European banking institutions with improved performance in the environmental and social pillars are characterized by lower beta coefficients and higher Return on Equity (ROE).

By employing Return on Assets (ROA) as the primary financial performance metric and panel regression analysis with two-stage least squares estimation to address endogeneity concerns, Saha et al. (2024) found that SDG alignment has a positive impact on financial performance across their sample of 100 companies spanning the finance, manufacturing, and technology sectors. Further research reveals that this relationship is strongest when companies move beyond disclosure to actual operational integration of SDG 9 principles into their business models, focusing on sustainable infrastructure, innovation, and inclusive industrialization (Jaruzelski et al., 2018).

Research has also explored the positive impacts of SDG 9 alignment on innovation ecosystems and knowledge creation, with numerous studies concluding that such alignment improves knowledge via technological innovation, sustainability reporting, and transferring knowledge to industry, which further enhances organizational learning (Giri & Chaparro, 2023; Pizzi et al., 2020; Raman et al., 2023; Zanten & Tulder, 2021). A further study undertaken by Denoncourt (2019) found that innovation in Spanish wine cooperatives, measured through digital presence and product diversification, has been a key factor in both SDG alignment and improved business performance (Denoncourt, 2019). Companies committed to SDG 9 objectives create substantial positive impacts in innovation and knowledge by fostering innovation ecosystems, facilitating knowledge transfer and capacity building, investing in R&D, developing digital infrastructure, and generating cross-sectoral spillovers (Denoncourt, 2019; Lehoux et al., 2018; Li et al., 2023). A more in-depth understanding of this process requires primary information sources and a more comprehensive research framework, facilitating a better understanding of the impact of SDG 9 in the innovation and knowledge fields (McGill, 2018).

The primary issues with existing research are the inconclusive results on the net impact of alignment or non-alignment with SDG 9 (Donkor et al., 2025; Yu et al., 2023), coupled with limited research on knowledge spillovers created by corporate innovation commitment and the critical gaps in standardized measurement of SDG 9 alignment across larger sets of companies which share heterogenous characteristics (Buil et al., 2024). We believe that the present study will enrich the existing literature on business alignment with innovation and infrastructure development by using SDG-aligned revenue share metrics as a consistent measure of SDG commitment across 5,323 unique companies, computed according to the methodology employed by Upright (details are provided in the Research design section).

Furthermore, our analysis overcomes the tendency for companies to report SDG 9 commitments on a more symbolic rather than substantive scale, which is one of the most preeminent SDG washing controversies (Waal et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2024). Companies tend to report on various SDG indicators without meaningfully integrating them with specific company goals or strategies; consequently, they do not connect their sustainability performance with either the services or products they offer, or the processes and business models used to produce them (Ferrero-Ferrero, 2023; Hachasanoğlu et al., 2024). In this respect, the SDG-aligned revenue share metrics employed in this study constitute an indicator computed at the company level by connecting the company’s product mix (i.e., revenue shares by product) with information on the SDG alignment classes of its products, according to the methodology employed by Upright.

A more detailed overview of all the metrics and indicators employed in our analysis is presented in the next section, which frames the research design and methodology of our study on SDG 9 alignment.

Research designOur research goal is to identify sectoral and geographical tendencies in organizations’ adherence to SDG 9. In this context, we exploited data from the Upright platform (https://uprightplatform.com) concerning 10,144 enterprises worldwide (Upright version 1.5.0). After aligning the company names from the Upright database with their primary sectors of activity and country of headquarters from the Orbis database, a total of 5,323 unique companies were incorporated in the analysis. All of these organizations are publicly traded on at least one stock exchange. The companies operate in all economic sectors, but the best represented sectors in the sample (the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) economic classification of sectors was used) are Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery with 702 companies (13.19 %), Business Services with 580 companies (10.90 %), and Banking, Insurance & Financial Services with 521 companies (9.79 % of the total). The countries with the most representation in terms of headquarters are the United States (1900 companies or 35.69 %), Japan (460 companies or 8.64 %), and China (357 companies or 6.71 %).

Upright offers data on companies’ alignment or misalignment with each of the 17 SDGs (further information on Upright’s methodology can be found at https://docs.uprightplatform.com/). This alignment or misalignment is provided by Upright as the share of revenues that is SDG-aligned or SDG-misaligned; therefore, depending on the products and services offered, it is possible for a company to be included in both categories.

The Total SDG-aligned revenue share (SDG_TA) and Total SDG-misaligned revenue share (SDG_TM) metrics are computed by Upright at the company level by combining the company’s product mix (i.e., revenue shares by product) with information on the SDG alignment classes of its products. The level of (mis)alignment is measured using a three-level scale (strong/moderate/weak) and the specific SDG target(s) it relates to are considered for each product. According to the Upright methodology, when computing the metrics related to the SDG_TA, strongly aligned products generally have a clear direct impact on the SDG in question. In contrast, moderately aligned and weakly aligned products have a lesser direct or indirect impact. This rule also applies to the SDG_TM; these metrics are displayed as a summary percentage, which is a weighted sum of the revenue share of products that are aligned or misaligned with the SDG. As shown in Eq. (1), there is a higher weight on strong misalignment or alignment depending on the case.

As mentioned above, a company may be included in either the aligned or misaligned categories, as well as in both, depending on the products and services offered, their degree of alignment with a specific SDG, and the share of these products and services in the company’s revenue.

For the current analysis, we calculated the net alignment of each company as the difference between SDG_TA and SDG_TM for SDG 9, which varies between -0.5 and 1. We further divided these companies in four main categories for analysis based on the level of net alignment: (1) strongly aligned companies (SA) with net alignment between 0.5 and 1 (565 companies); (2) moderately aligned companies (MA) with net alignment between 0.001 and 0.499 (2,534 companies); (3) not aligned companies (NA) with net alignment of 0 (1,909 companies); and (4) misaligned companies (MS) with net alignment below 0 (315 companies). These figures reveal that most firms in our sample are either moderately aligned or not aligned with SDG 9. It is important to note that none of the non-aligned companies have any revenue shares, either aligned or misaligned with SDG 9.

We used the impact on Society (S), Knowledge (K), Health (H), and Environment (E), collectively known as SKHE, and calculated by Upright for one of the years 2020 to 2024, to note that this calculation covers only one of the five years considered.

The impact on society (S) is measured through five main impact subcategories: jobs (S1), taxes (S2), societal infrastructure (S3), societal stability (S4), and equality and human rights (S5). Positive impacts are created under this dimension by companies that promote racial, economic, or gender equality or enhance human rights, while negative impacts refer to decreasing understanding among people or enabling armed conflict. In order to account for knowledge creation (K), Upright employs four subcategories: knowledge infrastructure (K1), creating knowledge (K2), distributing knowledge (K3), and scarce human capital (K4). Companies whose products and services enhance the creation, distribution, and maintenance of knowledge, information, and data are considered to have a positive impact, while negative impacts relate to the distribution of untrue or misleading information regarding the KI–K3 subcategories and a lack of staff members with rare skills and capabilities for the K4 subcategory. The health (H) dimension has five subcategories: physical diseases (H1), mental diseases (H2), nutrition (H3), relationships (H4), and meaning & joy (H5). Positive impacts across these subcategories are identified in the case of companies whose products and services contribute to treating, preventing, or contributing toward the treatment or prevention of diseases and food security, while also improving the quality of human relationships and sense of meaning. Negative impacts relate to causing diseases or injuries and worsening the quality of human relationships and experiences of joy. Finally, five subcategories are used for the environmental (E) dimension: emissions (E1), non-GHG emissions (E2), scarce natural resources (E3), biodiversity (E4), and waste (E5). Positive impacts are created via products and services that contribute toward the reduction of GHG emissions or water, land, and air pollution, saving or increasing the amount of highly scarce natural resources, or protecting biodiversity and animal welfare. Negative impacts refer to all types of waste, especially GHG emissions and contributions to water, land, or air pollution.

These categories are mutually exclusive, so each one incorporates impact indicators on specific benefits and costs. The total impact per category is obtained by extracting costs (negative impacts) from benefits (positive impacts); examples of costs include GHG emissions by a car factory or damage to human health caused by sugar-sweetened beverages, while benefits include improvements in health caused by a cancer medicine or pollution removed by a catalytic converter. For instance, to calculate the net impact a company has on creating knowledge (K2) as a subcategory of the Knowledge dimension (K), the following formula is used:

The impact values for each category are expressed in impact cents per dollar of revenue, which allows for comparability between impact categories as well as between companies. The cents represent the impact a company has in a particular category relative to its size.

The impact is calculated by Upright separately for all four dimensions using individual and aggregated SKHE scores. Further, the total net impact of a company is the net sum of costs and benefits that the company creates across all categories, leading to the Net Impact Sum (NIS):

Complementarily, the Net Impact Ratio (NIR) is calculated as follows:

Using these SKHE categories, we applied an advanced k-means clustering algorithm based on unsupervised machine learning to classify companies into homogeneous groups within the SA, MA, NA, and MS categories. The general objective of k-means clustering is to create groups that are as similar as possible to other entities (companies, in our case) included in the same group but also as dissimilar as possible from entities included in the other groups. This process produces a classification of entities that maximizes the similarity of entities that are included in a specific group.

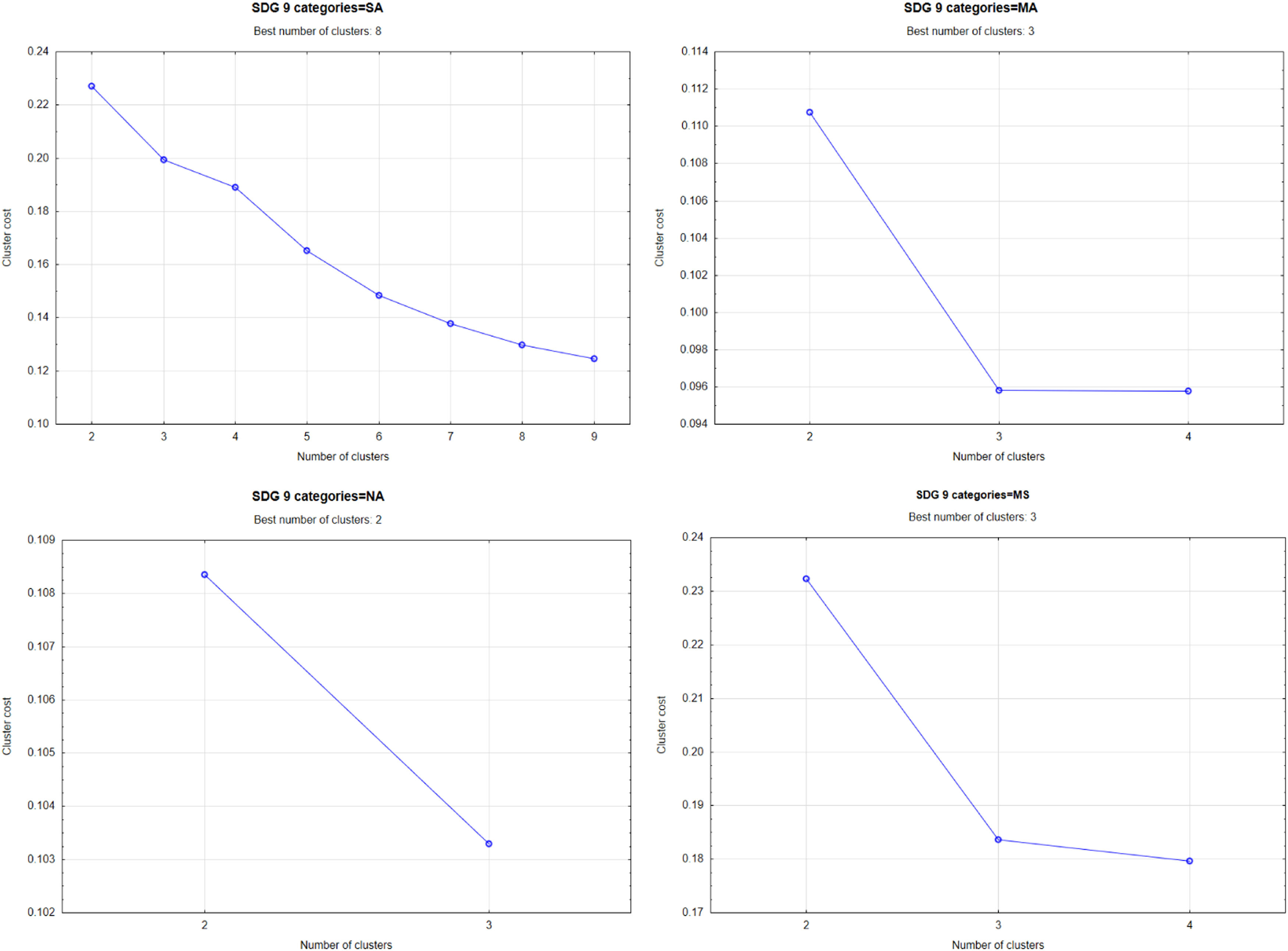

The k-means clustering algorithm used in the current research was implemented in Tibco Statistica and is grounded on the traditional k-means methodology proposed by Hartigan (2001). However, the algorithm uses Lloyd’s (1982) expected maximization (EM) method to form the clusters, embedded in the Generalized EM & k-Means Cluster Analysis module of Tibco Statistica. This extended approach has several advantages. First, compared to the traditional assignment of cases to clusters, the EM algorithm calculates probabilities of cases belonging to clusters that are found in one or more probability distributions, which maximizes the probability that a case will be included in a cluster. This procedure is based on maximum likelihood estimation and leads to an improved clustering solution, particularly when data distributions differ across clusters. Second, instead of the a priori specification of the number of clusters to be identified in the traditional k-means algorithm, which is a common limitation of the method, this approach uses a v-fold validation scheme built in Tibco Statistica to determine the optimal number of clusters based on the data provided and predictive performance. Specifically, the procedure repeatedly divides the data into v disjoint subsets (or folds) and for each candidate number of clusters within a predefined range (for our model, the range was 2 to 50), the clustering is performed on the remaining v-1 subsets (training data). The model is then assessed on the test data. Further, the process is iterated across all data subsets, and the average negative log-likelihood (the performance metric employed in this procedure) is aggregated across all iterations. The final number of clusters is determined when subsequent increases in the number do not return a statistically significant improvement in the model fit (for this study, the minimum decline in the error function between successive numbers of clusters was set at 5 %). Consequently, this EM-based methodology provides a data-driven and objective basis for identifying the optimal number of clusters without relying on a priori assumptions. A further benefit is that both continuous and categorical variables can be included in the clustering algorithm, whereas the traditional algorithm can only accommodate continuous variables. This algorithm has been applied to different fields in several scholarly papers, for example, Egerová and Nosková (2019), Steffelbauer et al. (2021), and Ammar et al. (2023).

Clusters were formed using Euclidean distance, which is the geometric distance in a multidimensional space. This is a popular distance metric that considers the dissimilarity between cases as follows:

where ED represents the Euclidean distance between x and y vectors (cases or companies in the present study), while xi and yi are the coordinates of the vectors x and y (the SKHE impact levels for each firm). Due to the scale homogeneity of the SKHE variables (coordinates), Euclidean distance is suitable for our data. In line with standard practice, all coordinates were standardized before being introduced to the clustering algorithm.For our linking approach we employed the Ward method, which minimizes the variance within clusters and begins cluster formation by considering that each case represents its own cluster (see Murtagh & Legendre, 2014). Iteratively, the method merges clusters that lead to the smallest increase in the within-cluster sum of squares. The resulting minimization of the within-cluster variance is one of the key advantages of this method compared to other linkage methods, such as single linkage or complete linkage. The Ward method is also more robust to outliers and noise and is highly compatible with the use of Euclidean distances (Jaeger & Banks, 2023).

For each category or alignment/misalignment with SDG 9 (SA, MA, NA, and MS), we applied the k-means clustering algorithm using the SKHE coordinates (as variables). To identify the patterns in each company’s alignment, the resulting clusters were further analyzed from the following perspectives: (1) the impact on each of the four SKHE coordinates (dimensions); (2) the countries in which the companies are headquartered; and (3) the main sector of the economy in which the companies operate. This assessment of clusters’ members is comprehensive and permits the identification of patterns in relation to both the specific levels of alignment with SDG 9 and the impact on the SKHE dimensions. We used the ANOVA methodology to test the statistical significance of the identified clusters and to understand the contribution of each coordinate to the result.

Considering the research gaps and research questions that are the foundation of our research, as well as the nature of the data, four main hypotheses were formulated:

H1: Higher SDG 9 alignment is associated with higher SKHE impact.

H2: SKHE impact profiles differ across sectors.

H3: SKHE impact profiles differ across regions.

H4: Distinct SKHE impact profiles emerge within SDG 9 alignment categories.

Fig. 1 presents the conceptual framework of our analysis and outlines the research hypotheses. It is important to note that, given the k-means clustering methodology employed, these hypotheses refer to associations rather than cause-and-effect relationships.

Results and discussionPreliminary resultsBefore presenting the results of the cluster analysis, it is necessary to provide an overview of the main company categories in relation to SDG 9 alignment. First, in terms of the division across the four main categories, the largest number of firms are found in the MA category (2,534 companies, or 10.61 % of the total), followed by NA (1,909 companies, 35.86 %), SA (565 companies, 10.61 %), and MS (315 companies, 5.92 %). Although the MS category is the smallest in terms of the number of companies, we note that there is no record of alignment with SDG 9 for a substantial number of companies. Second, in all categories, the largest number of companies are headquartered in the United States; however, their share of the total number of companies within each category varies considerably (46.4 % in SA, 35.4 % in MA, 34.1 % in NA, 28.3 % in MA). All statistics are presented in Table A1 in the appendix. Moreover, the majority of U.S.-based companies can be found within the MA and NA categories (898 and 651, respectively, 81.5 % of the total number of companies with headquarters in the United States), and only 13.7 % of them are included in the SA category. This pattern is observable for all other countries that are well represented in the sample (more than 100): the percentage of firms in the MA and NA categories varies between 73 % for Taiwan and 91.9 % for Finland. At the same time, there are several countries that are more strongly represented in the SA category, including Taiwan (24.6 %), Denmark (21.9 %), Norway (18.8 %), and Spain (18.2 %). As these countries are frequently cited in the literature as encouraging innovation and knowledge, a higher percentage of companies that are strongly aligned with SDG 9 compared to their country peers is expected (Hajighasemi et al., 2022; Soto, 2025; Yang, 2022).

Third, the distribution of companies across the 29 industries included in the analysis mimics the geographical distribution for all of the SDG 9 categories (see Table A2 in the appendix), with the exception of two firms that are entirely contained within the MA and NA categories. The shares of these two categories add up to 100 % for Textiles & Clothing Manufacturing and Printing & Publishing and decrease to 54 % for Mining & Extraction; however, the latter industry is the “leader” in the share of misaligned companies, with a share of 43 %. The exception is Biotechnology & Life Sciences; only 26 % of companies in the sample (129 firms) are included in the MA and NA categories, and 74 % of them are strongly aligned with SDG 9. Similarly, 75 % of the companies in the Waste Management & Treatment industry are included in the SA category. An interesting industry is Utilities, where only 43 % of firms are moderately aligned or not aligned with SDG 9, but most of the remaining firms are distributed in the MS category (32 % of the total), and 25 % are part of the SA category.

Existing research shows that knowledge creation is primarily concentrated in the financial services, business services, and industrial machinery sectors, with the United States, China, and Japan leading due to their strong innovation ecosystems and robust R&D investment (Campanella et al., 2019; Nguyen, 2024). The transportation and metals industries exhibit moderate knowledge creation with regional differences, such as India outperforming China in metals knowledge despite China’s larger export volume (Selamat et al., 2020). This trend highlights the role of deliberate innovation efforts beyond production scale. Industries such as food, tobacco, and retail display minimal systematic knowledge creation; this is often due to limited focus on R&D and organizational learning at the leadership level, which constrains their innovation potential despite their significant economic size (Gupta et al., 2022; Lagorio & Pinto, 2020). Resource-intensive sectors, such as mining, chemicals, and metals, emphasize capital and operational efficiency over knowledge-driven innovation, reflecting structural barriers that limit their strategic engagement with knowledge creation (Marín et al., 2015). These patterns highlight how leadership, sector characteristics, and national innovation capacities influence companies’ contributions to knowledge creation and alignment with SDG 9.

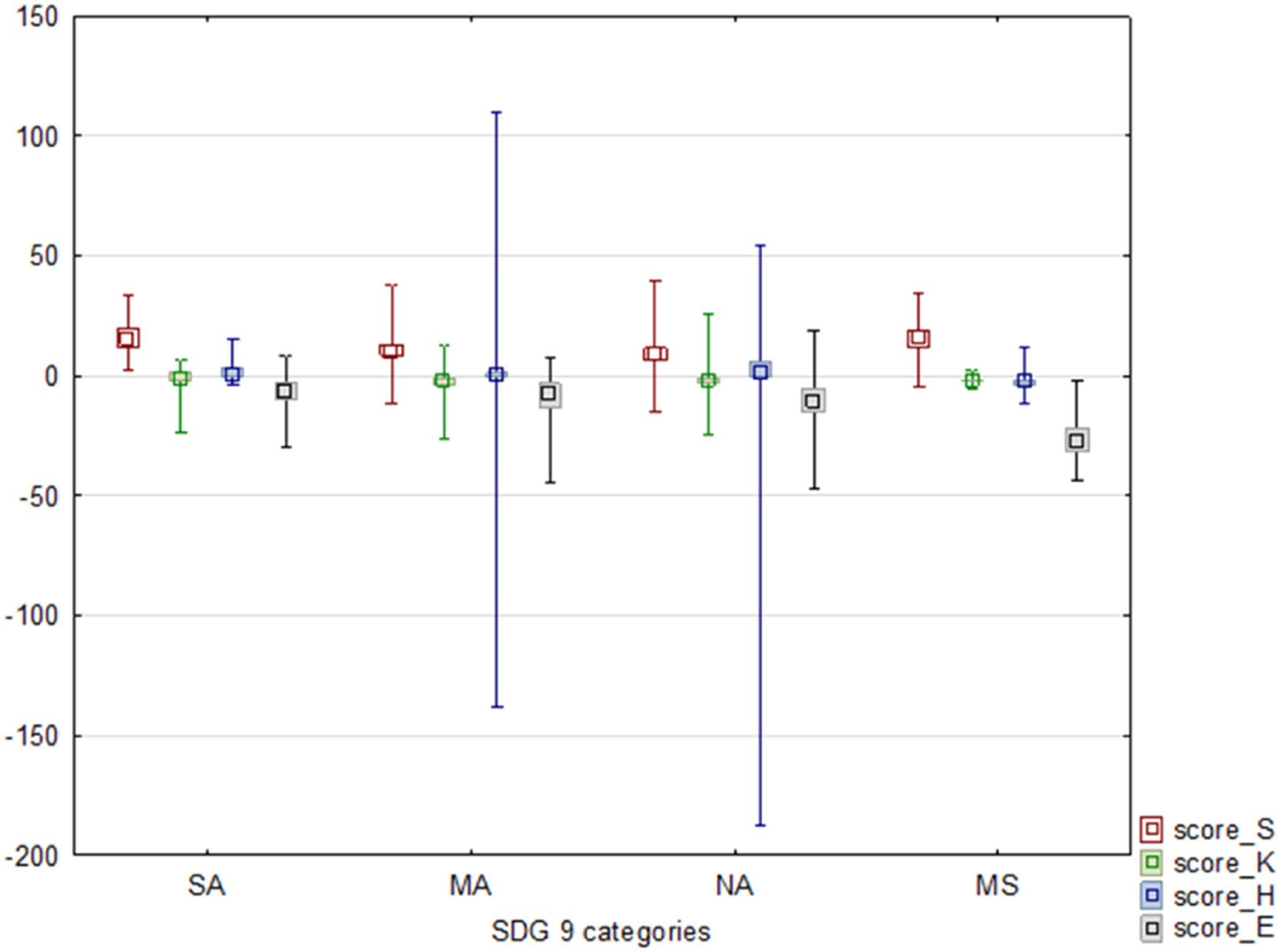

Companies included in the four categories also differ along the SKHE dimensions, as well as in terms of NIS and NIR. Fig. 2 presents the boxplots of the SKHE categories for each SDG 9 alignment category, and Table A3 in the appendix supplements them with descriptive statistics. When the SKHE dimensions are considered, all categories show a mean positive impact on society (S). Interestingly, the biggest means are for strongly aligned and misaligned firms. Moreover, three out of four categories (SA, MA, and NA) display a mean positive impact on health (H): the largest figure is for SA (2.90) and the lowest is for MA (1.32). For the MS category, we note a negative mean impact on H (-2.80). In the case of K and E dimensions, all mean impacts across SDG 9 categories are negative; this signals that, on average, the companies in our sample are not able to contribute to improving health and have a damaging effect on the environment. For the E dimension, the largest negative mean impact originates from the NA category (-26.60); this finding suggests that the lack of innovation and knowledge in business processes may go hand in hand with harming the environment, a conclusion also advanced in previous studies (Meidute-Kavaliauskiene et al., 2021; Horbach & Rammer, 2025).

In addition, the highest negative mean for the K dimension is recorded by firms in the MA category. This finding suggests that not being fully aligned with SDG 9 companies creates negative impacts in terms of knowledge, which is not a surprising result because SDG 9 fosters innovation and creates value in terms of digital technologies and knowledge. Moreover, this result has to be read in conjunction with the fact that our analysis does not consider interactions or (mis)alignment with other SDGs in exploring corporations’ impact across SKHE dimensions, which may provide valuable insights on important trade-offs across sustainable goals and negative impact creation. Another possible explanation for this negative mean could be the fact that declarative and superficial commitments to SDG 9, as opposed to integrated innovation strategies in business patterns, do not lead to innovation efficiency or knowledge creation (Kolk et al., 2017; Kazan et al., 2025; Van der Waal & Thijssens, 2020; Xing et al., 2024).

At the same time, there is a significant level of variation for some dimensions and SDG 9 categories. By far the largest ranges and standard deviations of impacts are shown by firms in the MA and NA categories in the H dimension, while the variation tends to be much smaller for the other dimensions.

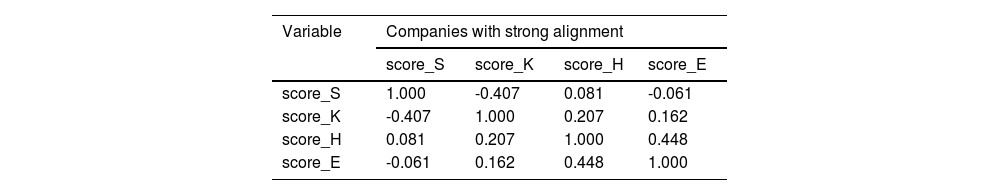

Finally, it is worth exploring the correlations between the different scores and dimensions depending on SDG 9 categories (see Table A4 in the appendix). The average correlations between the SKHE dimensions are positive for the SA, NA, and MS categories (0.072 and 0.015, respectively) and negative for the MA and MS categories (-0.050 and -0.055, respectively), which does not suggest a particular connection at a collective level across the four dimensions. At the pairwise correlation level, however, several higher and statistically significant correlations are evident: 0.689 and 0.448 between the E and H dimensions for misaligned and strongly aligned companies, respectively.

Cluster analysis resultsIn this section of the paper, we present the main findings regarding the patterns of corporate impact on the SKHE dimensions and the K1–K4 sub-dimensions of knowledge. As outlined in the Research Design section, we implemented EM based k-means clustering algorithms for each SDG 9 alignment category, producing four amalgamations overall.

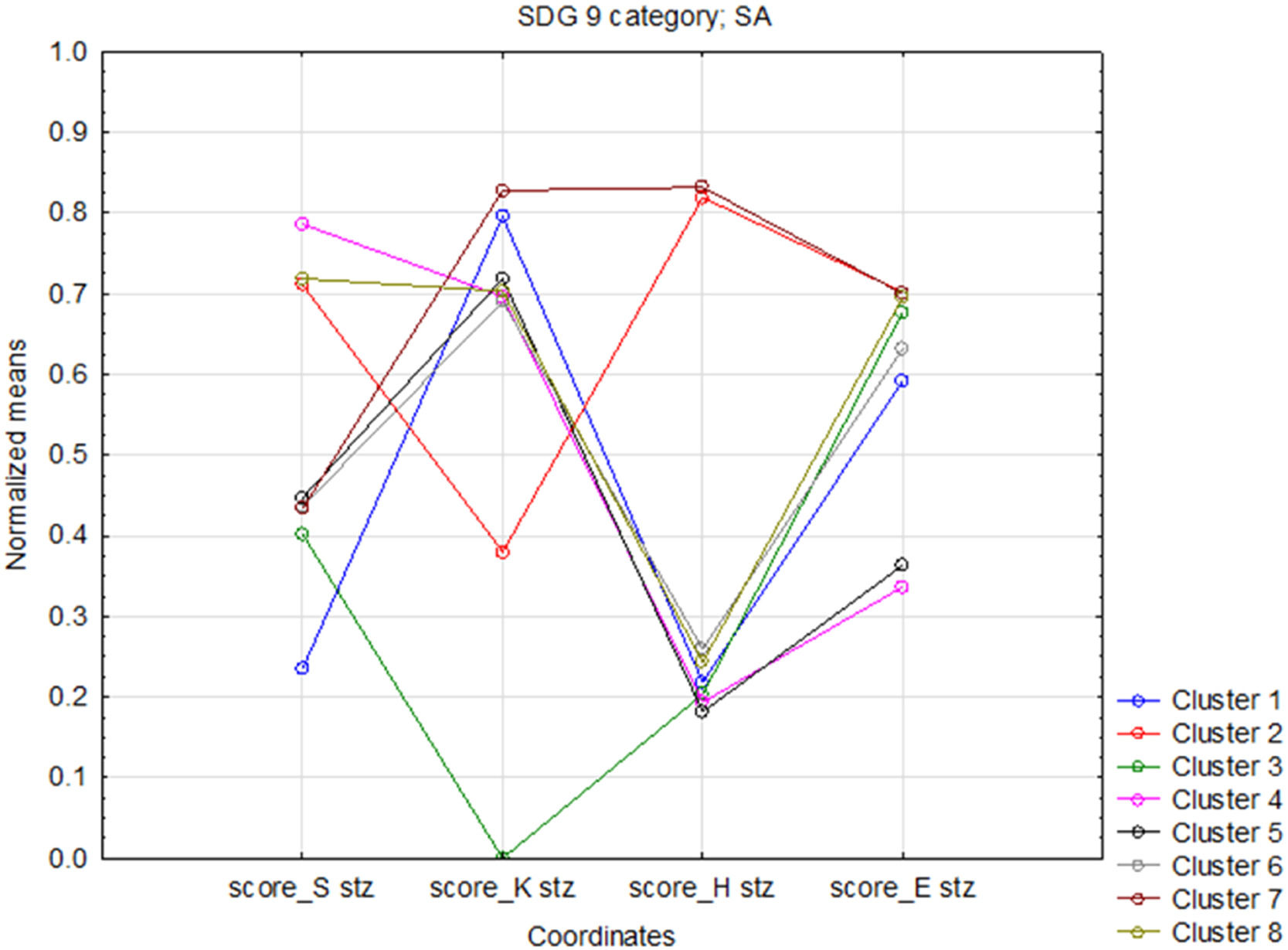

Table 1 shows the values of centroids for all clusters identified in the amalgamation within each SDG 9 alignment category. The highest number of clusters (eight) was found in the SA category, while three clusters were identified for MA and MS, and two were found for NA (Fig. A1 in the appendix presents the graphs of cost sequence for each amalgamation and the optimal number of clusters identified by the v-fold procedure). This suggests a higher heterogeneity of firms that are aligned with SDG 9 compared to those that are moderately aligned, not aligned, or misaligned. The average distances between centroids also point to increased heterogeneity for the clusters in the SA category; these distances vary between 0.167 for the NA category and 0.624 for the SA category. We present and discuss the results of the k-means clustering for each category of SDG 9 alignment throughout the remainder of this section.

Centroids for k-means clustering (standardized values).

Source: Authors’ work in Tibco Statistica

The eight clusters identified in the amalgamation showcase companies that are strongly aligned with SDG 9. Most firms belong to Cluster 1 (163 or 28.8 % of the firms in this category), Cluster 7 (116 or 20.5 %), and Cluster 6 (103 firms or 18.2 %). Cluster 3 includes only one firm, and this can be treated as an outlier. The remaining clusters range from 12 firms (Cluster 2) and 75 firms (Cluster 5).

Fig. 3 shows the means for the SKHE coordinates for each of the eight clusters in the SA category (data was standardized before clustering, hence the use of “stz” after coordinates names in the graph). There is a clear variation between clusters for all SKHE dimensions, and each cluster is differentiated from the others in at least one dimension, with no cluster showing a clear dominance. This shows that companies in this strong alignment category have different approaches to SDG 9 implementation. Most notably, Clusters 2 and 7 demonstrate the highest relative performance, with Cluster 2 being particularly strong in the S, H, and E dimensions (mean scores of 2.439, 1.047, and 0.957, respectively), while Cluster 7 shows companies that excel (on average) in the K, H, and E dimensions (scores of 1.402, 1.072 and 0.949, respectively). Cluster 2 primarily includes companies from two sectors: Biotechnology & Life Sciences (50 % of firms) and Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (33.3 %). They are accompanied by companies from the Wholesale and Transport, Freight & Storage sectors, each with a share of 8.33 %. From a geographical perspective, the companies in this cluster are headquartered in the United States (11 out of 12) and Finland (1 out of 12). For Cluster 7, which is much larger than Cluster 2 (116 companies), 76.7 % of firms come from the Biotechnology & Life Sciences sector, 19.8 % from Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic, and the remaining firms from Food & Tobacco Manufacturing, Business Services, and Public Administration, Education, Health, & Social Services sectors. The vast majority of these companies are headquartered in the United States (90.5 %), with other countries located in Sweden and Canada (2 firms each), and Singapore, Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, and India (1 firm each).

The largest cluster (Cluster 1, representing 28.8 % of strongly aligned companies) exhibits moderate performance across the K, H, and E dimensions; however, it also has the lowest performance in the S dimension of all clusters (-0.299). This indicates that many strongly aligned companies engage in a balanced but not necessarily exceptional approach toward SDG 9, a result that reflects existing evidence that companies emphasize existing R&D activities without necessarily connecting them to broader infrastructure and innovation priorities (Kolk et al., 2017; Ahsan & Qureshi, 2021; Kazan et al., 2025). A larger number of sectors are represented in this cluster, though none are particularly dominant. Five sectors have more than 10 companies: Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (56 companies or 34.4 %), Communications (37 companies or 22.7 %), Property Services (13 companies or 7.98 %), and Computer Hardware (12 companies or 7.36 %). Other sectors represented in the cluster include Metals & Metal Products and Wholesale (8 firms each), Transport, Freight & Storage and Computer Software (5 firms each), Construction (4 firms), Business Services, Banking, Insurance & Financial Services, and Media & Broadcasting (3 firms each), as well as Utilities, Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic, Mining & Extraction, Travel, Personal & Leisure, Leather, Stone, Clay & Glass products, and Retail (1 firm each). The majority of these firms are headquartered in the United States (57 firms or 35 %), Taiwan (22 firms or 13.5 %), and China (13 firms or 7.98 %), with other countries represented including the Cayman Islands (8 firms), Japan (7 firms), Israel (5 firms) Germany, and France (4 firms each), Australia, Bermuda, Finland, South Korea, and South Africa (3 firms each), Belgium, Switzerland, Denmark, the United Kingdom, India, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Sweden, and Singapore (2 firms each), and Canada, Egypt, Spain, Hong Kong, Kenya, and Mexico (1 firm each).

Meanwhile, smaller clusters like Cluster 4 (31 companies or 5.78 % of firms in the SA category) represent companies with highly specialized strategies that focus on the S dimension (the highest mean score is 2.870). A large proportion of companies allocated to this cluster come from Transport, Freight & Storage (11 firms or 35.48 %), Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (6 firms or 19.4 %), and Construction (5 firms or 16.13 %). Other sectors included in this cluster are Utilities (three companies), Business Services (2 firms), and Banking, Insurance & Financial Services, Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic, Transport Manufacturing, and Mining & Extraction (two companies each). Firms in Cluster 4 are headquartered in many countries, mostly in the United States (6 firms or 19.35 %), and China and South Korea (3 firms or 9.7 % each). Other represented countries are Germany, the Marshall Islands, Thailand, and Taiwan (2 firms or 6.5 % each), and the United Arab Emirates, Australia, Bermuda, Switzerland, Spain, France, Israel, India, Italy, the Cayman Islands, and Norway (one firm or 3.23 % each). Another interesting example is Cluster 8, which has the third-highest relative performance in the S and E dimensions among all clusters. The firms in this cluster have a strong alignment with SDG 9 and focus on society and the environment in their activities. This may also mean that innovation and knowledge are used as a lever in creating a positive impact on these dimensions. The firms in this cluster are from various sectors, including Utilities (29 firms or 45.3 % of the total) and Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (15 firms or 23.4 %), as well as Transport Manufacturing (4 firms), Business Services, Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic, and Mining & Extraction (2 firms each), and Communications, Banking, Insurance & Financial Services, Biotechnology & Life Sciences, Food & Tobacco Manufacturing, and Construction (one firm each).

The varying cluster sizes and performance patterns suggest that a one-size-fits-all corporate approach toward innovation and impact on the SKHE dimensions is less realistic. However, multiple strategic approaches are the norm for firms that are strongly aligned with SDG 9, ranging from a focus on particular dimensions to more balanced cross-dimensional strategies. At the same time, the sectoral concentration patterns provide important evidence for industry-specific approaches to sustainable development. The dominance of Biotechnology & Life Sciences firms in the high-performing Clusters 2 and 7, alongside their higher performance in the health and environmental dimensions, reflects the natural and expected alignment between this sector’s core activities and SDG 9 objectives. Additionally, the wider sectoral representation in Cluster 1, which demonstrates moderate overall performance across the four dimensions, indicates that diverse industries may propose balanced approaches to sustainability; this does, however, come at the cost of superior performance in a single dimension. Geographically, the overwhelming concentration of high-performing firms in the United States (particularly in the more dimension-specialized Clusters 2 and 7) suggests the presence of important institutional and contextual drivers that facilitate superior SDG 9 alignment. The geographical clustering of firms that are strongly aligned with SDG 9 may be the result of the support provided to sustainability strategies by regulatory frameworks, innovation ecosystems, and capital market structures. This result, which contrasts with existing studies indicating that EU companies exhibit higher SDG 9 alignment scores compared to global averages (Hahn & Kühnen, 2013; Kraemer et al., 2022), has important implications regarding the prominent role of regulators and supervisory authorities in providing a strong regulatory framework that further creates institutional pressures in terms of SDG alignment.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the heterogeneity across clusters is complemented by within-cluster heterogeneity. All four SKHE dimensions exhibit substantial ranges for some clusters, which reinforces the heterogeneity in corporate approaches to SDG 9 implementation evidenced by the differences between clusters. The K (knowledge) dimension appears to display the highest variation, with the lowest minimum value in Cluster 3 and some of the highest positive scores, suggesting this may be the most discriminant factor among clusters. The ANOVA methodology applied to the k-means clustering confirms this, while also indicating that all four dimensions are strong differentiators between clusters (see Table A5 in the appendix). On the other hand, the H (health) and E (environment) dimensions have more moderate ranges across the majority of clusters, indicating that firms with strong alignment with SDG 9 in these dimensions have a more homogeneous impact. This clustering pattern supports the finding that firms do not adhere to a dominant integrated approach to SDG 9 alignment; instead, they pursue specific strategies that address particular dimensions while underperforming in others.

These findings align with existing research on corporate sustainability strategy heterogeneity (Satar et al., 2024; Horobet et al., 2024), which shows that firms adopt differentiated approaches based on their tangible and intangible assets, capabilities, competitive position, and stakeholder pressures. The observed patterns also support the resource-based view perspective that sustainable competitive advantages emerge from unique combinations of resources and capabilities rather than standardized practices (Hart & Dowell, 2011). These processes encourage competition among the major economic players (the United States, China, and Japan, or the American economy versus the Asian economies). An economy can maintain its leading status by constantly establishing new technologies and innovating through knowledge creation (Hana, 2013).

Clustering results for moderately aligned companiesThe k-means algorithm distributed the 2,534 firms that are moderately aligned with SDG 9 in just three clusters. As shown in Table 1, the highest number of companies is included in Cluster 2 (1,109 or 43.8 % of the total), followed by Cluster 3 (784 companies or 30.9 %), and Cluster 1 (641 companies or 25.3 %). The means of the SKHE clustering coordinates are shown in Fig. 5.

The SKHE centroids portray a differentiation between clusters that is dominated by the E (environment) dimension, followed by the S (society) and K (knowledge) dimensions, while almost no differentiation is observable in the H (health) dimension. Similar to the SA category, no cluster outperforms the others in all dimensions. However, each cluster excels in one or two dimensions: Cluster 1 has the strongest mean performance in terms of S (score of 0.0643), Cluster 2 performs well in terms of K and H (scores of 0.454 and 0.132, respectively), and Cluster 3 has a strong E score (0.948). At the same time, Cluster 1 records the worst relative performance on H and E (scores of -0.243 and -0.974, respectively), while Cluster 3 demonstrates the worst performance in terms of S and K (-0.575 and -0.936, respectively). Conversely, Cluster 2 displays moderate performance for the S and E dimensions.

Compared to the SA category, the sectoral and geographical distribution of firms in the MA category is more balanced. Cluster 1, which displays the best performance in terms of S, moderate K scores, and weaker H and E scores, includes firms from 22 sectors. The dominant sectors are Transport, Freight & Storage (104 firms or 16.22 %), Transport Manufacturing (90 firms or 14.04 %), Metals & Metal Products (76 firms or 11.86 %), and Utilities (53 firms or 8.27 %). Other well represented sectors include Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (53 firms), Construction (45 firms), Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (41 firms), Retail (30 firms), Wholesale (28 firms), Business Services (20 firms), Leather, Stone, Clay & Glass products (19 firms), Food & Tobacco Manufacturing (12 firms), and Travel, Personal & Leisure (10 firms). All other sectors are represented by fewer than 10 firms in this cluster. Geographically, companies in Cluster 1 are mostly headquartered in the United States (120 firms or 18.7 %), Japan (112 firms or 17.5 %), China (63 firms or 9.83 %), South Korea (27 firms), and India (22 firms or 3.43 %). All other countries in this country have fewer than 20 firms, with the best represented being Taiwan (18 firms), Australia (17 firms), Canada and Finland (16 firms each), Germany (14 firms), Brazil, France, and the United Kingdom (13 firms each), and Norway, Sweden, and Singapore (each with 10 firms).

Cluster 2, which performs moderately in the S, H, and E dimensions yet displays the best performance in the K dimension, also consists of firms from 22 sectors; however, the distribution is different compared to Cluster 1. Most firms operate in the Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery sector (292 or 26.33 % of the total), followed by Property Services (114 firms or 10.28 %), Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (105 firms or 9.47 %), Business Services (93 firms or 8.39 %), and Communications (87 firms or 7.84 %). This result, which implies that firms operating in these industries create significant knowledge value when they are aligned with the SDG 9 goals, is particularly significant for corporate managers aiming to pursue efficient business practices to facilitate the innovation and knowledge that will eventually enhance their firms’ financial performance.

In fact, the sectoral distribution in this cluster is in line with previous results showing that technology and telecommunications companies, together with manufacturing firms, demonstrate the strongest commitment to SDG 9 through mature integration practices that enhance innovation and knowledge (Garcia-Macia & Sollaci, 2024; Kazan et al., 2025; Vázquez et al., 2024). A particular example is the ICT Sustainable Development Goals Benchmark, developed by Huawei; in an assessment of how the firm’s ICT solutions promote SDG goals, this benchmark identified SDG 9 as having the biggest correlation with ICT sectors alongside SDG 3 and SDG 4 (Huawei Annual Report, 2023).

Other well-represented sectors in Cluster 2 are Computer Software (40 firms), Wholesale (39 firms), Transport Manufacturing (37 firms), Metals & Metal Products (34 firms), and Retail (30 firms). Other sectors have fewer than 30 firms in this cluster. From a geographical perspective, a significant percentage are based in the United States (404 firms or 36.4 % of the total), followed by Japan (126 firms or 11.36 %), China (65 firms or 5.96 %), Sweden (44 firms or 3.97 %), Germany and Finland (40 firms or 3.61 % each), the United Kingdom (38 firms or 3.43 %), and Australia (31 firms or 2.8 %). The remaining countries have fewer than 30 firms in this cluster. Similar results regarding how SDG 9-aligned companies create knowledge spillovers in these particular markets have been obtained by Audretsch and Belitski (2022), who analyzed 15,430 firms in the United Kingdom from 2002 to 2014 and concluded that SDG 9-aligned companies primarily create knowledge and innovation externalities via R&D investment.

For Cluster 3, the best performer in E, the sectoral distribution of companies is skewed toward Banking, Insurance & Financial Services (333 firms or 42.47 % of the total) and Business Services (312 firms or 39.8 %). Both are service sectors, and similar results have been reported in the literature. In the banking sector, Zanten and Tulder (2021) show that Indonesian banks have intensified their SDG 9-related strategies, particularly in supporting micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in innovative projects, even though integration of technology and innovation into core strategies remains limited. Furthermore, Migliorelli (2021)) highlights the upward trend of green landing in SDG 9-aligned projects by concluding that green bonds and sustainability-linked loans increasingly target SDG 9-related projects, which may explain the enhanced performance in the E dimension within our study. Other important sectors in this cluster include Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (42 firms or 5.36 %), Computer Software (18 firms or 2.3 %), Communications (12 firms or 1.53 %), and Utilities and Property Services (11 firms or 1.4 % each).

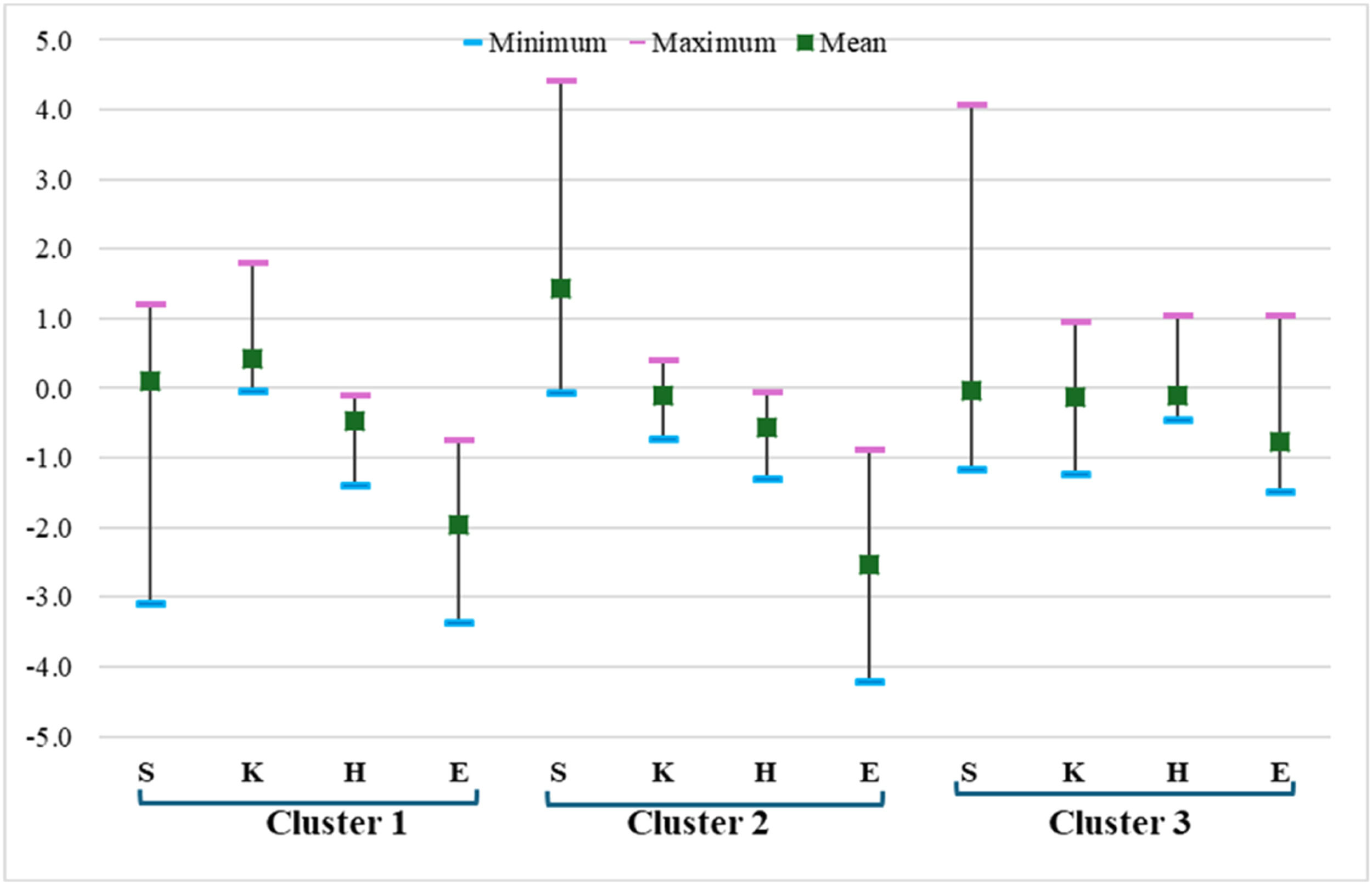

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the within-cluster variation for moderately aligned firms is different across the four dimensions. The H and K dimensions display the highest range in Clusters 2 and 3, but the smallest in Cluster 1; this indicates a higher homogeneity of firms in Cluster 1 with respect to these two dimensions. Interestingly, the within-cluster variation is the smallest in all three clusters for the E dimension, while the S dimension has moderate variation. The ANOVA methodology confirms these variations and shows that all dimensions have differentiating power across clusters (see Table A5 in the appendix).

The clustering analysis of moderately aligned companies reveals a distinct landscape compared to strongly aligned firms, featuring reduced complexity and clearer trade-offs across the SKHE dimensions. The presence of only three clusters, compared to the eight observed in the SA category, suggests that firms in this category have more constrained impact options and can deploy a less sophisticated level of sustainability engagement. The dominance of the E dimension as a differentiator among the MA clusters indicates the precedence of E considerations as visible and measurable aspects of sustainable development connected to innovation adoption. Similar results are evident in the literature (Meidute-Kavaliauskiene et al., 2021; Horbach & Rammer, 2025). At the same time, the relative lack of differentiation in the H dimension points to health impacts as secondary concerns or issues requiring advanced capabilities that moderately aligned firms have yet to develop. The sectoral patterns identified in the MA clusters, with a concentration of manufacturing and industrial sectors in Cluster 1 (focused on societal impact) and service sectors in Cluster 3 (displaying the best environmental performance), suggest that sectoral characteristics have a significant influence on the dimensions companies can impact. This aligns well with the resource-based theory, indicating that firms use their existing capabilities and competitive positions when developing sustainability strategies (Barney, 1991). It also aligns with further research that points to the sector or industry of activity as a strong determinant of sustainable or ESG corporate commitment (Martiny et al., 2024).

The more balanced geographical distribution of misaligned firms compared to strongly aligned companies implies that although sustainability performance is globally compatible with a moderate commitment to SDG 9, a supportive institutional framework may be required to achieve superior performance in innovation. This may also indicate a wider availability of basic capabilities related to sustainability; however, the higher performance in terms of sustainability remains concentrated in particular countries.

Clustering results for non-aligned companiesThe k-means clustering algorithm applied to the firms not aligned with SDG 9 shows the highest homogeneity of companies that are distributed in two clusters (see Fig. 7). More than half of the 1,909 companies can be found in Cluster 1 (1,011 firms or 53 % of the total), while the remaining 898 firms (47 %) are included in Cluster 2. There are substantial differences in the E coordinate between the two clusters, with normalized means of 0.615 for Cluster 2 and -0.782 for Cluster 1. This indicates superior performance for companies in Cluster 2. A weaker but still statistically significant differentiator between the two clusters is the H dimension, with Cluster 2 again performing better. The other two dimensions do not have a significant discriminant power (see Table A5 in the appendix for ANOVA results), indicating a high level of similarity between the two clusters.

Considering all SKHE dimensions, Cluster 2 records a higher impact compared to Cluster 1. The firms included in Cluster 2 operate in all 29 sectors included in the sample, with strong representation in the Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (176 firms or 17.4 % of the total), Banking, Insurance & Financial Services (138 firms or 13.6 %), Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (117 firms or 11.6 %), and Business Services (104 firms or 10.3 %) sectors. Other well-represented sectors include Public Administration, Education, Health, & Social Services (77 firms), Property Services (72 firms), Travel, Personal & Leisure (52 firms), Wholesale (42 firms), and Media & Broadcasting (36 firms). All other sectors have fewer than 20 firms in this cluster. Most firms have their headquarters in the United States (407 firms or 40.3 %), Japan (69 firms or 6.8 %), and China (55 firms or 5.44 %). Countries with more than 20 but fewer than 50 headquartered firms include Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Cayman Islands, Finland, Sweden, and France, while the remaining countries are represented by fewer than 20 firms. Comparatively, most Cluster 1 companies are distributed in the Retail (122 firms or 13.5 %), Food & Tobacco Manufacturing (121 firms or 13.5 %), Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic (89 firms or 9.9 %), Mining & Extraction (85 firms or 9.5 %), and Metals & Metal Products (80 firms or 8.9 %). A further 11 sectors have between 20 and 79 firms, while the remaining sectors contain fewer than 20 firms (seven sectors are not represented in this cluster). The country distribution of firms in the two clusters follows a clear pattern in line with the clusters in the previous categories; the United States is ranked first, although with a higher relative presence in Cluster 2 (244 firms or 27.7 % of firms in Cluster 1 and 407 firms or 40.3 % in Cluster 2). China is ranked second in Cluster 1 (86 firms or 9.2 % of firms) and Japan in Cluster 2 (69 firms or 6.8 %). Other countries with a substantial presence in Cluster 1 include Japan (77 firms), Australia (50 firms), the United Kingdom (40 firms), and India (38 firms) in, while in Cluster 2 China (55 firms), the United Kingdom (49 firms), Sweden (42 firms), and the Cayman Islands (39 firms) are well represented.

Fig. 8 shows the within-cluster variation among the SKHE dimensions for companies not aligned with SDG 9. Clearly, there is higher heterogeneity among firms in Cluster 2 in the S, K, and H dimensions, while the variation is similar for E.

Briefly, the resulting amalgamation of non-aligned companies exposes the simplest impact structure within the SKHE dimensions, with a binary classification of firms differentiated primarily by environmental performance. The considerable environmental impact differential between the two clusters (0.615 versus -0.782) highlights an important divide between firms that do not have products or services incorporating the features relevant to innovation and knowledge and those that do. Sectoral patterns point to sustainability engagement barriers that are sector-specific, with traditional sectors such as retail and manufacturing concentrated in the lower-performing Cluster 1. Similar to moderately aligned companies, the higher U.S. representation in Cluster 2 implies an institutional impact on sustainability performance. This result reflects the findings of previous studies such as Rahi et al. (2023 and Azam et al. (2021).

Clustering results for misaligned companiesMisaligned companies were grouped into three clusters, with the majority in Cluster 2 (170 or 54 %), 91 firms in Cluster 1 (29 %), and the remaining 54 firms in Cluster 3 (17 %). As shown in Fig. 9, Cluster 1 is well differentiated from the other two in all dimensions, while Clusters 2 and 3 are clearly differentiated in the S, H, and E dimensions but are very similar in terms of the K dimension. As is the case for the SA and MA categories, no cluster dominates in all four dimensions.

The distribution of different sectors in the three clusters shows distinct patterns. In Cluster 1, the majority of firms are from Mining & Extraction (50 firms or 55 % of the total), accompanied by companies in the Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic sector (16 firms or 17.6 %) and Metals & Metal Products (6 firms or 6.6 %). Other sectors with at least one company included in this cluster include Industrial, Electric & Electronic Machinery (5 firms), Transport, Freight & Storage, Utilities, Business Services, Wholesale, and Leather, Stone, Clay & Glass products (2 firms each), and Communications, Banking, Insurance & Financial Services, Transport Manufacturing, and Miscellaneous Manufacturing (each with one firm). More than half of firms in Cluster 2 operate in the Utilities and Mining & Extraction sectors (31 % and 25.3 % of firms, respectively), followed by Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic with 18.2 % of companies. The remaining sectors represented in this cluster have at most 10 firms included: Wholesale, Business Services, Retail, Banking, Insurance & Financial Services, Food & Tobacco Manufacturing, Property Services, Construction, Metals & Metal Products, Leather, Stone, Clay & Glass products, Retail, and Wood, Furniture & Paper Manufacturing. The Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic sector clearly dominates Cluster 3 with 25 firms (46.3 %). Other important sectors in this cluster include Retail (5 firms) and Business Services (4 firms), while eight other sectors have fewer than 4 firms. From a geographical perspective, the United States is dominant with 36.3 % in Cluster 1, 25.9 % in Cluster 2, and 22.2 % in Cluster 3. Other well-represented countries include Japan (9 firms in Cluster 3 and 12 firms in Cluster 2), China (18 firms in Cluster 2 and 9 firms in Cluster 1), and the United Kingdom (7 firms in Cluster 1).

Given that these are clusters of firms that are misaligned with SDG 9, these distributions direct us toward the industries and regions that struggle most with innovation alignment. The concentration of extractive and resource-intensive industries in all three clusters suggests that traditional industrial sectors are facing considerable challenges in adopting innovation as well as transitioning toward sustainable practices. Moreover, the dominance of Mining & Extraction firms in Cluster 1 and their significant presence in Cluster 2 (25.3 %) indicates that this sector faces difficulties in terms of alignment with SDG 9’s innovation and sustainability objectives, likely connected with business models that prioritize short-term profits over long-term sustainability and environmental engagement (Azmat et al., 2023; Baninla et al., 2025). Similarly, the large representation of Chemicals, Petroleum, Rubber & Plastic in all clusters points to the multifaceted challenge of transforming carbon-intensive industries (Saraji & Streimikiene, 2023). Further, the significant presence of traditional industries in the MA category suggests limited knowledge transfers from more progressive sectors in terms of innovation, potentially indicating a need for targeted policy interventions and the identification of industry-specific sustainability transition pathways (Amegboleza & Ülkü, 2025; Mani et al., 2024).

The geographic concentration of firms in the United States in all three clusters suggests that corporate and sectoral resistance to SDG 9 alignment remains high, even in developed economies with advanced institutional frameworks. This pattern may reflect specific business models, regulatory inertia, or market structures that preserve unsustainable practices despite the availability of innovation-related resources and capabilities (Benito & Meyer, 2024; Hamdouna & Khmelyarchuk, 2025).

The within-cluster variation presented in Fig. 10 highlights the significant disparity among firms in the S dimension for all clusters. According to the ANOVA, this dimension is the most important differentiator of clusters (see Table A5 in the appendix). In second place is the E dimension with important variations in all clusters, while the K and H dimensions have relatively low levels of variation. In connection with the fact that these are companies misaligned with SDG 9, these results indicate that societal impact is the primary area in which innovation and knowledge-misaligned firms diverge most considerably. They also suggest that social responsibility might represent the most important challenge for these companies. Moreover, the substantial variation in the E impact indicates inconsistent corporate approaches to sustainability among these firms.

Policy implicationsThe heterogeneity in corporate SDG 9 alignment across regions and industries suggests that universal policy interventions may not be sufficient. Rather, policymakers should develop sectoral approaches based on variable innovation and digitalization capabilities. For example, biotechnology and life sciences, with high alignment levels and higher SKHE effects, can take advantage of R&D tax schemes and knowledge transfer programs, whereas the mining and extractive sectors may benefit from more stringent regulatory requirements and transition sustainability methods (Grodzicki & Jankiewicz, 2024; Liang et al., 2023). Furthermore, the integration of Industry 5.0 and cutting-edge technologies (e.g., AI, IoT, VR) with industrial and services segments can promote the objectives of SDG 9. Nonetheless, implementation costs and skills gaps remain key hindrances. Public policies should include upskilling programs, financing for small and medium companies, and technology diffusion incentives in order to expand access to innovation infrastructure (Bhuyan et al., 2025; Costa, 2024).

At the country level, high-performing countries such as the United States, Finland, and Denmark, which have high firm-level compliance with SDG 9, enjoy stable national innovation systems and beneficial institutional arrangements. In contrast, governments of emerging economies must invest in higher education, patent facilities, and public–private research studies to upgrade national innovation systems and shift companies from moderate to high compliance with SGD 9 (Ahmed et al., 2024; Burhan, 2023).

The study shows that misaligned and moderately aligned firms commonly have harmful effects on both knowledge and the environment, which might be due to superficial or symbolic SDG commitments or even innovation washing. Therefore, transparency and a common SDG audit criterion must be imposed on the sustainability reporting process to prevent greenwashing and innovation washing and ensure that alignments with SDG 9 are substantiated with concrete actions (Denoncourt, 2019; Kazan, Kocamış & Öker, 2025).

The evidence that several companies perform well in all four SKHE dimensions indicates that the integration of SDG into ESG assessments may prove valuable in terms of capital allocation decisions. In this vein, capital market authorities should work with stock exchanges to integrate SDG-compliant disclosures into ESG ratings, thereby incentivizing investors and encouraging sustainable financial flows (Gunawan et al., 2024). Policy intervention is particularly essential in resource-intensive industries (e.g., mining, chemicals) and in regions with underdeveloped innovation ecosystems. Transition pathways must be delineated for these sectors, encompassing green subsidies, the expansion of digital infrastructure, and collaborations between industries and universities to enhance innovative capabilities (Edbais & Hossain, 2025; Soliyev & Makhmudov, 2024).

ConclusionsThis study explores sectoral and regional disparities in terms of business alignment with SDG 9, which challenges innovation and infrastructure development while contrasting impact and value creation in relation to the four SKHE dimensions. By using SDG-aligned revenue share metrics as a consistent measure of SDG alignment across 5,323 listed companies, our analysis addresses the most pre-eminent issues in this area in terms of measurement complexities regarding sustainability engagement and high heterogeneity in reporting among companies and industries.