Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is one of the most common chronic diseases in childhood.1,2

The incidence of childhood T1DM varies markedly around countries2–4; however studies assessing temporal trends have shown a consistent increase in all parts of the world (average relative increase of 3–4% per calendar year).3,4 At the same time, the age at onset is decreasing.4

The age of presentation of childhood-onset T1DM has a bimodal distribution, with one peak at pre-school age and a second in early puberty.5 Approximately 45% of children are diagnosed before 10 years of age.6

Although the majority autoimmune diseases are more common in females, there seems to be no gender difference in the overall incidence of childhood T1DM.1,2 In some studies, a 1.3–2.0-fold male excess in incidence after 15 years of age is observed (similar to the incidence in young adulthood).4,7

The management of children and adolescents with T1DM has unique challenges, requiring monitoring in pediatric departments with expertise in the disease, in order to obtain a truly interdisciplinary care and family support, as needed.8 When caring for children with T1DM, it is important to take into account the age and developmental maturity of the child.

The initial care phase may occur either in the inpatient or ambulatory setting. Over the years, most institutions have moved from prolonged inpatient admissions for newly diagnosed patients to short hospitalizations, day hospital settings or ambulatory management.9

Quality improvement programs in pediatric diabetes, based on the establishment of a system for benchmarking of diabetes treatment, can lead to significant improvements in management and the quality of screening assessments.10

In the pediatrics department of our hospital, children and adolescents with an inaugural episode of T1DM are admitted to the pediatric ward for better medical management, initial diabetes education and self-care training. In order to define an initial management plan and promote shorter periods of hospitalization (ideally 4 days), an integrated care process (ICP) was designed and implemented in 2015. The ICP is a patient-centered, multidisciplinary process that aims to guide attitudes, identify responsibilities and standardize the care provided. This institutional protocol was elaborated according to the 2014 clinical practice consensus guidelines of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD).11

To evaluate the utility of the ICP, we conducted a quality improvement program which intended to assess four previously defined indicators and the rate of compliance to the ICP during hospitalization in a pediatric department of a level II hospital. A target of at least 80% compliance for all 4 indicators was established.

MethodsThis was a retrospective study developed in a level II hospital of the Portuguese National Health Service, based on the clinical records of all the children and adolescents with an inaugural episode of T1DM, over a period of 4.5 years (between January-2015 and July-2019). The pediatric department of this hospital develops its activity in different sectors such as outpatient clinic, pediatric ward (total of 26 beds)/nursery and emergency room, with an average of 1033 admissions per year.

Study variablesThe included variables were: age, gender, length of stay, nursing and medical care, nutritional management, social services evaluation, multidisciplinary team intervention, discharge preparation and compliance with four predefined indicators: 1. >70% of blood glucose 70–180mg/dl at discharge; 2. patient/caregiver knows how to assess capillary glucose; 3. patient/caregiver knows how to administer insulin; 4. patient/caregiver knows how to detect and correct hypoglycemia. For the first indicator, based on available literature,12 we established a target percentage of at least 70% glycemic evaluations during the day within the parameters of glycemic goals (70–180mg/dl). Regarding compliance with indicators 2–4, there were no formal evaluation moments, instead it was a continuous process of increasing autonomy from patients and parents and the nursing staff summarized improvements on routine daily shift notes, which were available for consultation afterwards by the rest of the team.

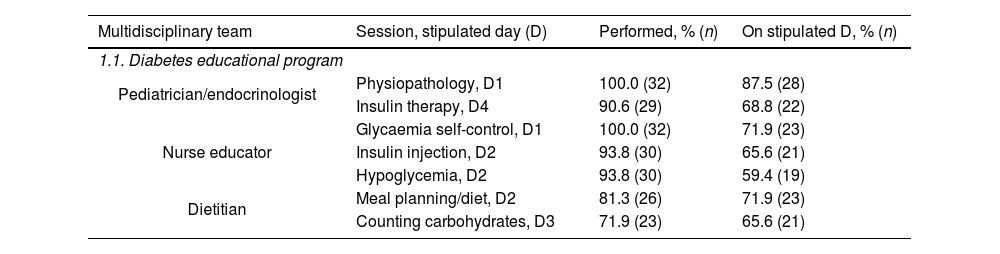

Integrated care processAs part of the ICP program, there are educational periods stipulated in the hospitalization calendar that provide the patient and family with the knowledge and skills needed for routine care. There are seven formal sessions of initial diabetes education and self-care training provided by a multidisciplinary team: pathogenesis of T1DM, insulin therapy, glycaemia control, insulin injection, hypoglycemia, meal planning/dietary counseling and carbohydrates counting.

While preparing the discharge of the patients, several issues were considered and handled by the health care professionals in order to promote the best transition to independent self-management with support from the family and diabetes care team – national database registration, visiting the outpatient clinic, proof of disability for allowance, prescription of Diabetic Guide, information for school, contacting the Health Care Center, providing written therapeutic information, pediatric and dietitian appointments, nurse discharge papers and providing emergency contacts.

The ICP attitudes may not apply in specific situations, such as establishing contact with the family doctor of the primary care center and the school (for example, if the family has recently moved/immigrated to the region and therefore has no family doctor or the child does not attend school yet).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was carried out for all descriptive values. Continuous values were represented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, as appropriate. Discrete variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. The Spearman or Pearson correlation tests were used for continuous variables, as appropriate. All p-values were two tailed and considered significant if <0.05. All analysis were performed in SPSS 22 (IBM).

ResultsWe included 32 children/adolescents hospitalized in the pediatric department with the diagnosis of T1DM – inaugural episode, that represent all the cases observed during the study period in our hospital's area of influence, with a mean incidence of 7.1 cases per year (minimum 4 cases, maximum 8 cases).

From our sample, 22 (69%) were male and the mean age was 10±4.8 years (minimum 23 months old, maximum 17.7 years old). The median length of stay was 5 days (IQR 2 days, range 3–12 days). A correlation was found between age of the patient and length of hospitalization (p=0.004).

The contents of the ICP form implemented in our department and the rate of accomplishment are summarized in Table 1.

Components and results of the integrated care process during hospitalization.

| Multidisciplinary team | Session, stipulated day (D) | Performed, % (n) | On stipulated D, % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1. Diabetes educational program | |||

| Pediatrician/endocrinologist | Physiopathology, D1 | 100.0 (32) | 87.5 (28) |

| Insulin therapy, D4 | 90.6 (29) | 68.8 (22) | |

| Nurse educator | Glycaemia self-control, D1 | 100.0 (32) | 71.9 (23) |

| Insulin injection, D2 | 93.8 (30) | 65.6 (21) | |

| Hypoglycemia, D2 | 93.8 (30) | 59.4 (19) | |

| Dietitian | Meal planning/diet, D2 | 81.3 (26) | 71.9 (23) |

| Counting carbohydrates, D3 | 71.9 (23) | 65.6 (21) | |

| Attitudes, stipulated day (D) | Performed, % (n) | On stipulated D, % (n) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.2. Preparation for clinical discharge | ||

| DOCE registration, D2 | 65.6 (21) | 59.4 (19) |

| Visit to the outpatient clinic, D3 | 96.9 (31) | 62.5 (20) |

| Proof of disability for allowance, D3 | 100.0 (32) | 71.9 (23) |

| Prescription of Diabetic Guide, D3 | 96.9 (31) | 90.6 (29) |

| Information for school (only 29), D3 | 89.7 (26) | 62.1 (18) |

| Contact Health Care Center (only 28), D3 | 85.7 (24) | 60.7 (17) |

| Written therapeutic information, D4 | 93.8 (30) | 65.6 (21) |

| Pediatric and dietitian outpatient appointments, D4 | 96.9 (31) | 68.8 (22) |

| Nurse discharge papers, D4 | 78.1 (25) | 50.0 (16) |

| Emergency contacts, D4 | 78.1 (25) | 59.4 (19) |

| Indicators | % (n) |

|---|---|

| 1.3. Quality ICP indicators | |

| 1. Patient is discharged with >70% of glycaemia values in the range 70–180mg/dL | 84.4 (27) |

| 2. Patient/caregiver knows how to prick the finger and evaluate capillary glucose | 87.5 (28) |

| 3. Patient/caregiver knows how to administer subcutaneous insulin | 87.5 (28) |

| 4. Patient/caregiver can detect and properly correct hypoglycemia | 87.5 (28) |

D: day; D1: first day; D2: second day; D3: third day; D4: fourth day.

DOCE (Diabetes: registO de Crianças e jovEns) – Portuguese national registry of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and youth.

Most of the sessions were performed at some point during hospital stay, but the difference in the number of sessions that were actually held on the day recommended by the ICP is noticeable. A total of 22 sessions out of 224 (9.8%) were not performed, most of them concerning the nutritional part of the program (n=15).

Only 66% (n=21) of the inaugural episodes were reported, during hospital stay, to the national registry of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in children and youth: DOCE (Diabetes: registO de Crianças e jovEns).

Consultation with a dietitian with experience in pediatric nutrition and diabetes is an important component of diabetes care, with around 77% (n=25) dietary inquiries and 59% (n=19) meal planning's performed.

When the health care professionals felt necessary, a social worker was asked to help deal with the new diagnosis and all the socioeconomic implications. This collaboration with the social services was considered unnecessary in 12 cases. Regarding the remaining patients (n=20), only 5 were assisted.

The medical standard of care (conducting the initial clinical interview, writing the medical history and daily clinical records, prescription of therapeutic and its adjustments) was performed in 100% of the cases. Concerning the routines of the nursing staff, reception of patients in the pediatric ward and general care was accomplished in 100% of shifts while specific diabetes practical training was accomplished in 69% of shifts.

Finally, the target goal of >80% compliance to the four indicators was surpassed, with discriminated results in Table 1 (section 1.3).

DiscussionIn our paper, we found that the ICP was correctly implemented and its results are promising, despite there still being room for improvement.

Overall, the health care professionals from our pediatric department had a good performance regarding the key concepts of the ICP. The assessed indicators met the target of at least 80% compliance, reflecting the quality of care provided in our institution.

In the study period, 32 cases of inaugural T1DM were registered, with discrete annual variations. Contrary to other studies,2–4 the results did not show an increase in the incidence rate of the disease in our hospital but our study is not adequately powered to study this effect.

Management of newly diagnosed diabetes in children and adolescents is divided into two phases.13 Our work is focused on the initial phase of T1DM management that begins at the time of diagnosis, when the family begins to understand the disease process and is trained to safely manage diabetes (measure blood glucose concentrations, administer insulin, recognize and treat hypoglycemia). The final assessment of the multidisciplinary teaching sessions in the ward, which originated a great opportunity to educate the patients and their caregivers on several matters, demonstrated a gap regarding the nutritional issues. For instance, as the dietitian team was not available during the weekend, some patients were discharged without attending the nutritional formative sessions. The authors recognize this as a limitation of a smaller hospital, which can be further improved upon. Nevertheless, information about alimentation and carbohydrates counting was transmitted by other healthcare staff.

As a complementary tool for the information in sessions, multimedia support such as website references (support groups for parents and patients with the new diagnosis, associations regarding DMT1 in pediatric population) and PowerPoint presentations prepared by the healthcare team were provided.

For the second phase, a comprehensive management by a pediatric diabetes care team is of the utmost importance, so that the patient and family can get further education and support to optimize glycemic control and long-term self-care. Furthermore, it reduces the number of hospitalizations and emergency room visits and is cost-effective.14,15 In our study, the measures considered in the ICP for discharge preparation are important to promote the transition to the outpatient setting and long term follow-up. Those measures were mostly accomplished in our population. For instance, all patients but one were provided with pediatric and dietitian outpatient appointments as part of their follow-up, which also serve as opportunities to further consolidate their knowledge. However, we believe that some measures can still be implemented to facilitate increased adhesion by the healthcare staff, such as regular sessions about the ICP key points. The Portuguese national registry (DOCE) was filled for 66% of patients and although it is a fundamental part of the ICP for characterization of T1DM prevalence in our country,16 it can be filled at a later appointment.

Even though most ICP's procedures were performed during hospital stay, the percentage of which ones were held on the stipulated day was significantly inferior, leading to hospitalization duration of >4 days. No doubt, length of hospitalization depends on the learning rhythm of the families, which is influenced by non-modifiable factors, such as patient age, cognitive ability, emotional maturity and parents socioeconomic status, and by a series of other variants related to the impact of T1DM diagnosis and the pediatric ward itself, which can be modified to create a supporting and friendlier environment.11 The implemented ICP aims for shortest inpatient periods as possible, standardized attitudes of health care staff, maximized support and guidance to children/adolescents and caregivers in the ward, but it is always adjusting to the particularities of each family and eventual time-limiting barriers.

There are some limitations to our study, such as the reduced sample size and the use of data from clinical records, with inherent biases and missing data. We would like to emphasize that the correct filling of the ICP form was a bureaucratically complex process, so part of the procedures not performed could probably be explained as registration gaps. With this in mind, after the period contemplated in this study, the ICP was reformulated to a check-list form, more intuitive and easier to fill. The authors hope to improve healthcare providers adhesion with this measure.

In conclusion, most of the defined ICP's measures related with the initial management of T1DM in a pediatric ward were achieved in our hospital. The ICP process is essential as hospitalization can be an opportunity to promote good self-care habits to be subsequently maintained at home. Moreover, the positive results obtained encourage the health care team to maintain the good work.

FundingThere were no external funding sources for the realization of this paper.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

PresentationsThe present study was presented as an oral communication on the 20° Congresso Nacional de Pediatria, in November 2019, in Lisbon, Portugal.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest in conducting this work.

To all staff of the pediatric ward that contributed to the study aiding in the ICP measures implementation.