Anxious depression (AD), a common neurophysiological subtype of major depressive disorder (MDD), is often accompanied by immune dysregulation and volumetric alterations in brain structures. However, the intrinsic relationships between inflammatory markers and brain structural changes in AD patients remain unclear.

MethodsParticipants were categorized into three groups: the AD group (n = 43), the non-anxious depression group (NAD, n = 68), and healthy controls (HC, n = 53), matched for age, sex, and education level. Serum levels of interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were measured across the groups. All participants underwent T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis was performed to assess gray matter volume (GMV). Correlation analyses were conducted to investigate potential associations between inflammatory markers and GMV in the AD group.

ResultsCompared to HCs, patients with MDD exhibited significantly elevated serum IL-6 levels. Additionally, AD patients demonstrated reduced GMV in the right putamen, right superior temporal gyrus (STG), and right cuneus compared to both NAD and HC groups. Notably, reduced GMV in the right STG was significantly correlated with serum IL-1β levels and depression severity within the AD group.

ConclusionsThese findings provide preliminary psychoradiological evidence for the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying this MDD subtype and possible explanations for the differences in clinical features and prognosis between AD and NAD.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common mental illness that is typically characterized by persistent low mood, loss of interest in activities, and cognitive impairments (Gnanavel & Robert, 2013). MDD is highly prevalent, affecting over 322 million individuals globally (Friedrich, 2017). According to a World Health Organization’s (WHO) report, MDD is projected to become the leading cause of global disease burden by 2030 (Organization, 2008). Despite its widespread impact, the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of MDD remain challenging due to its poorly understood etiology.

In recent decades, there have been considerable progresses in elucidating the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying depression. The pathogenesis of MDD is multifaceted, with a variety of factors potentially leading to the development of depression in individuals (Cui et al., 2024; Malhi & Mann, 2018). Briefly, previous studies have reported that the occurrence of MDD is always accompanied by immune dysregulation (Leonard, 2018; Setiawan et al., 2015; Sforzini et al., 2025) and volumetric alterations in brain structures (Schmaal et al., 2017). However, due to the diverse clinical manifestations of MDD, current hypotheses or findings cannot satisfactorily account for all aspects of the disease. Within this context, previous functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies have identified several neurophysiological subtypes corresponding to different clinical symptom profiles (Drysdale et al., 2017; Tozzi et al., 2024), among which anxious depression (AD) is a common subtype (Gaspersz et al., 2018). It has been estimated that 50–75 % of patients with MDD meet the DSM-5 criteria for AD (Hopwood, 2023). Compared to non-anxious depression (NAD), patients with AD have worse psychosocial functioning (Zimmerman et al., 2014), lower quality of life (Braverman et al., 2024), more severe symptoms (Goldberg et al., 2014), poor antidepressant treatment outcomes (Fava et al., 2008), and a higher risk of suicide (Gaspersz et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2024). Therefore, patients with AD may have different pathophysiological mechanisms from those with NAD. Exploring these unique pathophysiological mechanisms is expected to provide a theoretical foundation and potential therapeutic targets for individualized diagnosis and precise treatment.

Previous studies have demonstrated the relationship between inflammation and AD. Animal studies have shown that mice with induced inflammation exhibit anxiety- and depressive-like behavior (He et al., 2023; Ji et al., 2022; Matsumoto et al., 2021). Similarly, a study in rats found that pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), would confer susceptibility or vulnerability to depression and anxiety (Rebai, Jasmin & Boudah, 2021). Further, a large cohort study of 150,383 participants from the UK Biobank and NESDA demonstrated that elevated levels of C-reactive protein were associated with depression and anxiety symptoms (Milaneschi et al., 2021). Another study reported that patients with AD had reduced basophil subfraction compared to NAD, and the reduced basophil subfraction was significantly negatively correlated with Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) anxiety/somatization factor scores (Baek et al., 2016). These findings collectively suggest the involvement of inflammation in the development of AD.

Meanwhile, neuroimaging studies have indicated structural abnormalities in AD patients. Structural MRI studies revealed that AD patients displayed gray matter volume (GMV) changes in the cortical-limbic loops, including the superior frontal gyrus, orbital frontal gyrus, postcentral gyrus, superior temporal gyrus, cuneus, hippocampus, and the caudate nuclei (Juan et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2017). In a non-clinical population, GMV of the prefrontal-parietal, temporal, visual, hippocampus, and putamen could predict depressive and anxiety symptom scores (Zhang et al., 2024). In addition, these brain structural alterations have a shared genetic architecture with depression and anxiety phenotypes (Harrewijn et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2024).

In summary, this evidence indicated that both inflammation and structural abnormalities in the brain contribute to the onset and development of AD. However, most studies to date have only examined the inflammation or brain structures in the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD. Few studies have investigated the intrinsic relationships between the aberrant inflammatory cytokine levels and structural brain changes in AD. Peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines could cross the blood-brain barrier and act directly on neurons and supporting cells (e.g., astrocytes and microglia) to affect brain structures (Miller & Raison, 2016). Although limited, several studies have begun to explore the relationship between inflammatory cytokines and brain structural alterations in depression. For instance, a study with large-scale evidence found an association between low-grade peripheral inflammation and brain structural alterations in patients with MDD, especially in the anterior cingulate cortex and prefrontal regions (Opel et al., 2019). Similarly, a recent review reported that peripheral inflammatory markers are related to reduced cortical gray matter and subcortical volumes and cortical thinning within depression-related neural loops (Han & Ham, 2021). These findings suggest that peripheral inflammation may contribute to neuroanatomical alterations in depression, supporting the hypothesis that immune dysregulation and brain structural changes are interconnected in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. In this context, we measured three serum pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and performed unbiased whole-brain voxel-based morphometry (VBM) analysis. The concentrations of serum cytokines and GMV were compared among the AD, NAD, and healthy controls (HC). Finally, we explored the potential association between these biological determinants within the AD group. Combined with previous neuroimaging studies, we hypothesized that there could be a relationship between increased inflammatory cytokines and brain structural atrophy within the AD group.

Materials and methodsParticipants126 patients with MDD were recruited from Beijing Huilongguan Hospital, and 66 HC participants were recruited from the local community. Experienced psychiatrists conducted psychiatric diagnoses of the MDD patients using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV-TR) criteria (Sheehan et al., 1998). On the day of the experiment, symptom severity of MDD was evaluated with the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD-17) (Hamilton, 1967). The inclusion criteria for MDD patients were as follows: (1) age in the range of 18 to 55 years old; (2) drug-naïve patients with first-episode depression or recurrent depression with continued withdrawal of > 14 days; (3) a total score ≥ 14 on the HAMD-17. According to the score for the anxiety/somatic factor of the HAMD-17, the MDD patients were divided into two groups: the AD group and the NAD group. AD was defined as a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of MDD plus a HAMD-17 anxiety/somatic factor score ≥ 7, as previously detailed in the literature (Ionescu et al., 2013; Juan et al., 2024; Peng et al., 2019). The anxiety/somatization factor, which encompasses psychic anxiety (Item 10), somatic anxiety (Item 11), gastrointestinal somatic symptoms (Item 12), general somatic symptoms (Item 13), hypochondriasis (Item 15), and insight (Item 17), has been demonstrated to possess robust reliability in differentiating AD from other mood and anxiety disorders (Ionescu et al., 2013). HC participants were recruited via online advertisements. The inclusion criteria for HC participants were as follows: (1) age in the range of 18 to 55 years old; (2) no history of psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria. The exclusion criteria for all participants were as follows: (1) brain injury; (2) the existence of a neurological disorder; (3) serious medical illness; (4) pregnancy, breastfeeding, or preparing for pregnancy; (5) a history of substance abuse or dependence; and (6) any MRI-related contraindications. This study was approved by the independent Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital and the Human Ethics Committee of Beijing Huilongguan Hospital and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was acquired from all participants.

Serum pro-inflammatory cytokines measurementBlood samples were collected in standard coagulation tubes and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min, with harvested serum frozen at −80 °C for later analysis. Three pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) were measured by RayBiotech Company (Georgia, USA) in China. The clinical information was blinded in all procedures. Logarithmic transformations were used to standardize the data in order to lessen the impact of outliers.

Imaging acquisition and preprocessingAll MRI data were acquired on a 3.0 T Siemens Magnetom Prisma system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) at Beijing Huilongguan Hospital. High-resolution T1-weighted structural images were collected with a magnetization-prepared rapidly acquired gradient-echo (MPRAGE) sequence (slice thickness/gap = 1/0 mm, repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.28 ms, flip angle (FA) = 9°, matrix = 256 × 256, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm × 256 mm, 192 slices). All participants were asked to keep their eyes closed, lie still, and avoid dozing off during the scan.

We used the VBM 8 toolbox based on SPM 12 software for the preprocessing of structural images. T1-weighted structural images were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) standard brain template using diffeomorphic anatomical registration through exponentiated lie (DARTEL) algebra. Then, the normalized images were segmented into three tissue components, including the gray matter, the white matter, and the cerebrospinal fluid. Subsequently, we performed quality checks and nonlinear modulation for the segmented images. Finally, the images were smoothed with a 4-mm full width at half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian kernel (Lehmann et al., 2021; Salmond et al., 2002; Si et al., 2024). Among the initial 192 participants, 5 participants were excluded due to their unwillingness to provide blood samples, 9 participants were excluded due to incompleteness of the clinical data and MRI scan, 8 participants were excluded due to poor image quality, and 6 participants were excluded due to excessive head movement. After these exclusions, 164 participants remained, including 43 AD patients, 68 NAD patients, and 53 HC participants. The sample size calculation was conducted using G*Power Win 3.1, with an effect size f of 0.25, α err prob of 0.05, and power (1 – β err prob) of 0.8. The required sample size was determined to be 159 participants.

Statistical analysesThe normal distribution tests were performed for continuous variables. To analyze the demographic, clinical, and biochemical data, we performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Kruskal-Wallis analysis for normally distributed variables and skewed distributed variables, respectively. Two-sample t tests were used to compare the HAMD-17 score and anxiety/somatic factor score between the AD and NAD groups. The chi-square test was used to assess categorical variables differences among the three groups.

DPABI v 8.1 was applied to test intergroup differences. We performed one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc correction to compare the GMV among the three groups with age, sex, years of education, total internal volume (TIV), and mean FD covariates. The Gaussian random field (GRF) theory was used to correct for multiple comparisons (voxel significance: p < 0.001, cluster p < 0.05). Partial correlation analyses were performed to determine the potential relationship between the pro-inflammatory cytokine levels and GMV changes within the AD group, controlling for age, sex, years of education, total internal volume (TIV), and mean FD. The significant level was set as p < 0.05, and the false discovery rate (FDR) was used to correct for multiple comparisons.

In addition, we performed a direct comparison between the combined patient group (AD + NAD) and the HC group to strengthen the clinical relevance of the findings (Supplementary Table 1 and Table 2).

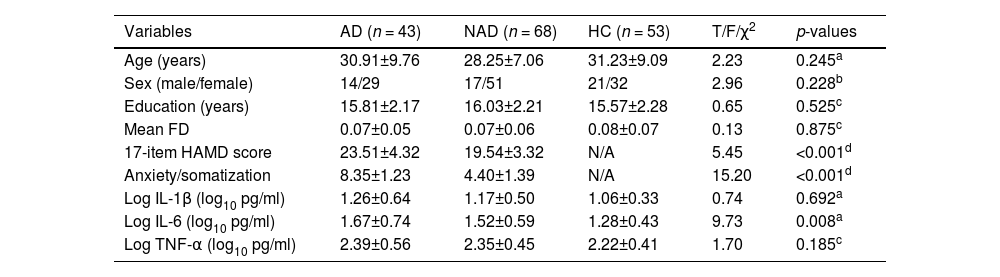

ResultsDemographic and clinical dataThe demographic and clinical data of all participants are shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age (p = 0.245), sex (p = 0.228), years of education (p = 0.525), and mean FD (p = 0.875) among the three groups. AD group showed increased HAMD-17 score and anxiety/somatic factor relative to NAD group (p < 0.001).

Demographic, clinical characteristics, and pro-inflammatory cytokines of participants.

| Variables | AD (n = 43) | NAD (n = 68) | HC (n = 53) | T/F/χ2 | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.91±9.76 | 28.25±7.06 | 31.23±9.09 | 2.23 | 0.245a |

| Sex (male/female) | 14/29 | 17/51 | 21/32 | 2.96 | 0.228b |

| Education (years) | 15.81±2.17 | 16.03±2.21 | 15.57±2.28 | 0.65 | 0.525c |

| Mean FD | 0.07±0.05 | 0.07±0.06 | 0.08±0.07 | 0.13 | 0.875c |

| 17-item HAMD score | 23.51±4.32 | 19.54±3.32 | N/A | 5.45 | <0.001d |

| Anxiety/somatization | 8.35±1.23 | 4.40±1.39 | N/A | 15.20 | <0.001d |

| Log IL-1β (log10 pg/ml) | 1.26±0.64 | 1.17±0.50 | 1.06±0.33 | 0.74 | 0.692a |

| Log IL-6 (log10 pg/ml) | 1.67±0.74 | 1.52±0.59 | 1.28±0.43 | 9.73 | 0.008a |

| Log TNF-α (log10 pg/ml) | 2.39±0.56 | 2.35±0.45 | 2.22±0.41 | 1.70 | 0.185c |

Abbreviations: AD, anxious depression; NAD, non-anxious depression; HC, healthy controls; FD, framewise displacement; HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IL, Interleukin; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor.

Table 1 presents the serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines for the three groups. Serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines were measured in 43 AD patients, 68 NAD patients, and 53 HCs. We observed significant differences in serum levels of IL-6 among the three groups (p = 0.008). The AD and NAD groups exhibited significantly higher serum levels of IL-6 compared with the HC group (p < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in serum levels of IL-6 between the AD and NAD groups. No significant differences in serum levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were observed among the three groups.

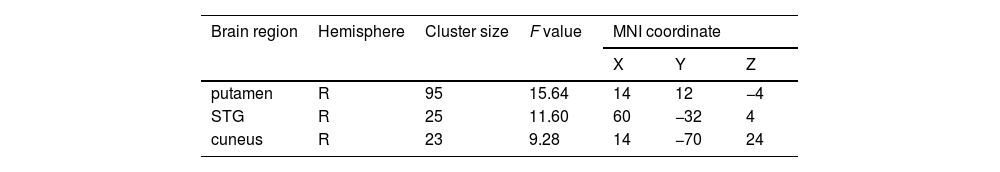

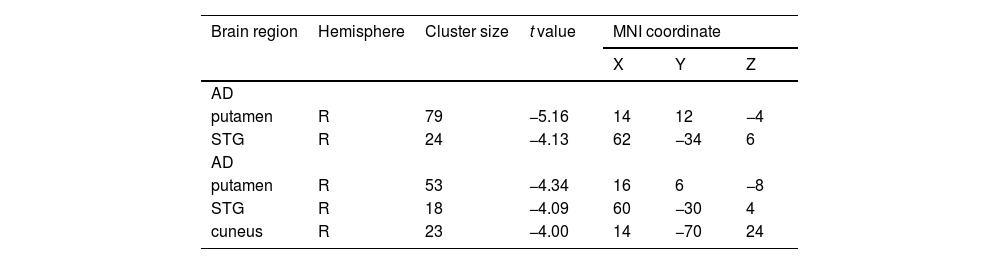

Gray matter volume differences among the three groupsAs shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2, we observed significant GMV differences in the right putamen, right superior temporal gyrus (STG), and right cuneus among the three groups. The post hoc analysis revealed that the AD group exhibited decreased GMV in the right putamen and right STG compared with the NAD group (Fig. 2 and Table 3). The AD group exhibited decreased GMV in the right putamen, right STG, and right cuneus compared with the HC group (Fig. 3 and Table 3). No significant GMV differences were observed between the NAD and HC groups.

Brain regions showing significant structural differences among three groups (voxel p < 0.001, cluster p < 0.05, GRF corrected).

| Brain region | Hemisphere | Cluster size | F value | MNI coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| putamen | R | 95 | 15.64 | 14 | 12 | −4 |

| STG | R | 25 | 11.60 | 60 | −32 | 4 |

| cuneus | R | 23 | 9.28 | 14 | −70 | 24 |

Abbreviations: MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; R, right; STG, superior temporal gyrus.

Brain region showing inter-group structural differences based on the results of ANCOVA (voxel p < 0.001, cluster p < 0.05, GRF corrected).

| Brain region | Hemisphere | Cluster size | t value | MNI coordinate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | Y | Z | ||||

| AD | ||||||

| putamen | R | 79 | −5.16 | 14 | 12 | −4 |

| STG | R | 24 | −4.13 | 62 | −34 | 6 |

| AD | ||||||

| putamen | R | 53 | −4.34 | 16 | 6 | −8 |

| STG | R | 18 | −4.09 | 60 | −30 | 4 |

| cuneus | R | 23 | −4.00 | 14 | −70 | 24 |

Abbreviations: MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; AD, anxious depression; NAD, non-anxious depression; HC, healthy controls; R, right; STG, superior temporal gyrus.

As shown in Fig. 4, the GMV in the right STG was positively correlated with the serum level of IL-1β in the AD group (r = 0.391, p < 0.05, FDR corrected). The GMV in the right STG was negatively correlated with the HAMD-17 in the AD group (r = −0.354, p < 0.05, FDR corrected) (Fig. 4). These associations were not significant in the other two groups (Supplementary Figure 1).

DiscussionTo our best knowledge, this is the first study to explore the intrinsic relationships between the serum concentrations of inflammatory markers and brain structural alterations in AD patients. Findings from the current study revealed increased peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokine and brain structural atrophies in the AD patients and indicated the relationships between the peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations and GMV changes. These findings suggest the involvement of inflammation and brain structural alterations in the pathogenesis of AD.

In this study, both AD and NAD groups exhibited elevated serum concentrations of IL-6 compared to HCs, which was in line with previous studies investigating the association between depression and inflammation (Furtado & Katzman, 2015; Roohi, Jaafari & Hashemian, 2021; Ting, Yang & Tsai, 2020). For example, Elgellaie et al. found that plasma IL-6 levels were higher in MDD compared with HC and correlated with the severity of depression and anxiety (Elgellaie et al., 2023). Similarly, a large-sample, longitudinal study found that IL-6 levels were significantly related to individuals' current symptoms of depression and anxiety (Lee, 2020). IL-6 is a well-known pro-inflammatory cytokine that plays a crucial role throughout the body's early phase of inflammation. Immune dysregulation and systemic inflammation are risk factors for mood disorders, including MDD and anxiety disorders. Depressive and anxiety symptoms are brought on in part by elevated IL-6 concentrations, as they trigger increased oxidative stress and hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Soygur et al., 2007). In addition, increased IL-6 activity could be a biological effect of psychological stress, which is the root cause of depression and anxiety (Butterweck, Prinz & Schwaninger, 2003). Although IL-6 levels were elevated in both AD/NAD groups, it was not significantly associated with GMV, which may suggest that IL-6 affects clinical symptoms through alternative, non-structural pathways. Potential mechanisms could include neurotransmitter regulation (particularly serotonin and dopamine systems) or functional neural network alterations rather than volumetric changes (Felger & Lotrich, 2013; Miller, Haroon & Felger, 2017). This interpretation aligns with emerging evidence suggesting that inflammatory markers may affect mood regulation through multiple distinct biological pathways (Paganin & Signorini, 2024; Yirmiya, 2024).

With respect to the neuroimaging findings in this study, AD patients exhibited significantly decreased GMV in the right STG relative to NAD and HC. The right STG is involved in emotional regulation (Narumoto et al., 2001), social cognition (Li et al., 2013), and spatial perceptual processing (Ellison et al., 2004). Previous structural MRI studies have demonstrated a reduction in the GMV of the right STG in patients with MDD (Kandilarova et al., 2019; Takahashi et al., 2010). Additionally, similar reductions in the GMV of the right STG have been observed in studies of anxiety disorders (Atmaca et al., 2021; Jianying et al., 2019). It can be speculated that the structure of the right STG is impaired in both depression and anxiety, which may support our current findings regarding individuals with AD showing lower GMV in the right STG compared to those with NAD. More interestingly, decreased GMV in the right STG was significantly correlated with the serum concentration of IL-1β and depression severity in the AD group. While no significant differences in IL-1β levels were observed across groups, the correlation of IL-1β and STG atrophy within AD may indicate a specific inflammatory-neuroplastic interaction in this group. IL-1β plays a critical role in neural plasticity, as it is involved in both inflammatory responses and the regulation of neuronal survival, synaptic pruning, synaptic transmission, and overall neural plasticity (Lima, 2023). Therefore, our findings indicate that inflammatory markers may impact neuroplasticity in specific subtypes of depression, and such impact could be realized through a variety of mechanisms. Notably, the observed positive correlation between IL-1β levels and GMV in AD appears paradoxical given previous reports of IL-1β's neurotoxic properties. IL-1β has been shown to modulate the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a neurotrophic that plays a pivotal role in neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity (Harsanyi et al., 2022). In the context of AD, elevated IL-1β levels might be part of a compensatory response aimed at enhancing neuroplasticity to counteract the detrimental effects of chronic stress and depression; that is, individuals with high IL-1β levels actually have less atrophied GMV.

Moreover, AD patients also showed significantly decreased GMV in the right putamen relative to NAD and HC. One previous positron emission tomography study supported our findings by showing the abnormal dopamine D2/3 receptor availability in the right putamen and its association with anxiety symptoms in MDD patients (Peciña et al., 2017). The putamen is involved in reward and fear processing via integrating inputs from the prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex (Haber & Knutson, 2010), and several “limbic” brain regions (Fudge, Breitbart & McClain, 2004; Shammah-Lagnado, Alheid & Heimer, 2001). The reward circuit plays an important role in the pathogenesis of depression, while the fear circuit is closely related to the generation of anxiety. Therefore, we speculate that the putamen of patients with AD may be more severely damaged compared to those with NAD. Taken together, it can be inferred that the putamen alterations could be an important and specific contributor to the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying AD. Similarly, AD patients exhibited decreased GMV in the right cuneus compared to HC, a brain region involved in social functioning and emotional facial processing (Parker, Zalusky & Kirbas, 2014). Weaker negative connections between the cuneus and median prefrontal cortex have been linked to impaired facial expression processing in patients with social anxiety disorder (Ding et al., 2011). A brain electromagnetic tomography study has reported that, compared with HC, patients with anxiety disorders showed abnormal activity in the cuneus, which underlies the processing of fearful faces (Yoon et al., 2016). Thus, our results of decreased GMV in the cuneus may be the structural basis for abnormal functions in this region (Wu, Zhang et al., 2024) and could explain deficits in social interaction and visual perception of AD patients, especially facial emotion.

There are several limitations to our study. First, as a cross-sectional study, we were unable to examine the dynamic changes in inflammatory markers and brain structure. Further longitudinal studies are expected to explore their causal relationship. Second, this is a preliminary study due to the small sample size. Future studies with larger sample sizes are essential to validate these findings. Third, we measured only three pro-inflammatory cytokines—IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α—resulting in a limited understanding of the inflammatory characteristics in patients with AD. Fourth, this study began prior to the release of the Chinese version of DSM-5. Therefore, when designing the experiment, the diagnostic criterion DSM-IV-TR, which was commonly used at that time, was adopted. However, the use of DSM-IV-TR may reduce comparability with the latest international research. Future study should use the DSM-5 or DSM-5-TR to ensure the timeliness and international comparability of the research results. Fifth, our study encompassed both first-episode, drug-naïve patients and relapsed patients who had been off medication for >14 days to minimize the acute effects of antidepressants on brain structure and inflammation. A washout period of at least 14 days is commonly used in neuroimaging studies to mitigate the acute pharmacological effects of antidepressants (Korgaonkar et al., 2020; Wu, Su et al., 2024), but long-term effects may persist. Future studies with longitudinal designs (tracking GMV and inflammation pre-/post-treatment) would be essential to clarify the causality. Sixth, this study only investigated gray matter. Future research should further combine free water imaging to explore its relationship with inflammation (Cao et al., 2025).

In this study, we observed elevated serum concentrations of IL-6 in patients with MDD and reduced GMV in the putamen, STG, and cuneus in AD patients. Furthermore, reduced GMV in the right STG was correlated with the serum concentration of IL-1β and depression severity in the AD group. These findings provide preliminary psychoradiological evidence for the pathophysiological mechanisms of this MDD subtype and possible explanations for the differences in clinical features and prognosis between AD and NAD, suggesting that both inflammation and brain structural changes are involved in the abnormal reward and fear processing, emotional dysregulation, and social functioning deficits of AD.

Declaration of generative AI in scientific writingIn order to improve the article's language and correct grammatical errors, the authors employed ChatGPT and QuillBot when preparing this work. Following the use of this tool or service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and took full responsibility for the publication's content.

Data availabilityThe data utilized in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethical standardsThis study was approved by the independent Ethics Committee of Peking University Sixth Hospital and the Human Ethics Committee of Beijing Huilongguan Hospital and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this experiment.

CRediT authorship contribution statementZhihui Lan: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Ji-Tao Li: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Project administration. Lin-lin Zhu: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration. Yankun Wu: Data curation, Investigation. Tian Shen: Data curation, Investigation. Youran Dai: Data curation, Investigation. Yun-Ai Su: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration. Tianmei Si: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization, Supervision, Validation, Project administration.

The authors declare no competing interests.

The authors thank the funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers: 82371530, 82271569, 82171529, and 82471544), Capital Foundation of Medicine Research and Development (grant number: 2022-1-4111), and the National Key Technology R&D Program (grant number: 2015BAI13B01).