Accumulative evidence has shown that functional heterogeneity exists in subregions of amygdala. Recently, exercise serving as automatic emotion regulation has been observed to induce the altered activation of amygdala associated with mood change. However, the specific role of subregions of amygdala underlying these effects are not fully understood. By using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), this study examined whether the subregions of amygdala play distinct roles in mood improvement induced by acute exercise.

Participants (n = 76) aged 18–22 were recruited and randomly divided into the exercise group and the control group. The exercise group received a 30-minute intervention with moderate-intensity exercise while the control group completed a reading control task at resting state. Whole-brain rs-fMRI scans were conducted before and after the interventions. Moreover, participants’ moods were also assessed using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) and Abbreviated Profile of Mood States. A mixed-effect model was used to analyze the Group × Time interaction on functional connectivity (FC) seeded from medial amygdala (mAmyg) and lateral amygdala (lAmyg) subregions in each hemisphere.

Results revealed that exercise-induced mood improvements were correlated with significant Group × Time interaction effects on FC, showing a notable right-hemispheric predominance. Specifically, enhanced connectivity of the right mAmyg with orbitofrontal cortex, parietal, and cerebellar regions was associated with reduced negative affect and increased self-esteem. Concurrently, enhanced connectivity of the right lAmyg with the orbitofrontal cortex and striatum was linked to a broad spectrum of improvements, including reduced tension and anger, and increased vigor.

These findings suggest that acute exercise improves mood via distinct, lateralized neural pathways centered on different amygdala subregions. The mAmyg and lAmyg play complementary roles in automatic emotion regulation, with the right mAmyg modulating affective valence and self-evaluation, while the right lAmyg appears to regulate a broad spectrum of mood states and enhance positive arousal. This work provides a more nuanced neurobiological model for the therapeutic effects of exercise.

Emotion regulation refers to an individual’s ability to influence emotions in oneself by activating a goal to modify the emotion-generating process (Gross, 1998; Gross et al., 2011). It is crucial for social interaction and mental health in human beings (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005) and could be divided into voluntary (deliberate) and automatic (largely unconscious) components (Phillips et al., 2008). Voluntary regulation requires conscious effort and deliberate control (Gross, 2015). In contrast, automatic regulation operates unconsciously, driving emotional changes without intentional decision-making or focused attention (I. Mauss et al., 2007; I.B. Mauss et al., 2007). It effectively reduces negative emotions, supporting emotional balance in daily life.

Acute aerobic exercise has immediate and short-term effects on mood, by reducing negative mood such as anxiety, depression, tension, and anger (Berger & Motl, 2000; Ensari et al., 2015), and by increasing positive affect like energy and well-being (Bartholomew et al., 2005; Reed & Ones, 2006). Such observations are consistent with the traditional hedonic models of emotion regulation, which focuses on maximizing pleasure (positive states) and minimizing psychic pain (negative states)(Larsen, 2000). Evidently, the mood change induced from acute exercise can serve as an efficient approach of automatic emotion regulation.

An increasing number of studies have focused on exploring the neural mechanisms underlying the mood change associated with acute aerobic exercise. Existing literature have partly identified several brain regions and functional networks influenced by acute exercise. Key brain regions involved include the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (Fumoto et al., 2010), amygdala (Tempest & Parfitt, 2017). Additionally, acute aerobic exercise has been shown to modulate specific functional connectivity (FC), such as the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) -temporal FC (Ligeza et al., 2021), amygdala-insula FC (Schmitt et al., 2020), and amygdala-orbitofrontal cortex FC (Ge et al., 2021). In view of these existed evidence, most studies consistently observed significant functional change in the amygdala. For instance, previous research has suggested that during cognitive reappraisal tasks, resources in the prefrontal region are mobilized to inhibit amygdala activity(Kohn et al., 2014), with some studies indicating that this modulation may be more pronounced with increased aerobic exercise intensity(Tempest & Parfitt, 2017). Additionally, acute aerobic exercise has been suggested to enhance the functional connectivity between the amygdala and other brain regions, such as the prefrontal cortex or insula(Ge et al., 2021; Schmitt et al., 2020), which was also associated with improved emotion regulation and reduced negative mood. Notably, regular aerobic exercise could enhance the plasticity of key emotion regulation pathways, including those involving the amygdala. It is assumed that this plasticity could contribute to better control over emotional responses and improved mood regulation(Wang et al., 2024).

The amygdala, an almond-shaped structure deep within the temporal lobe, assumes responsibility for emotional regulation, implicit emotional learning, emotions-related attention and emotion perception (Phelps & LeDoux, 2005). The amygdala plays a crucial role in processing emotional salience, generally showing increased activity in response to a wide array of emotionally significant stimuli, both negative and positive (Varkevisser et al., 2024). While increased activation is commonly observed, specific affective states, such as romantic love, have been associated with decreased amygdala activity in some fMRI studies (Bartels & Zeki, 2000; Šimić et al., 2021). It is important to note that the amygdala is not a structurally homogeneous entity but rather comprises diverse subregions or nuclei, each holding distinct functions (Bzdok et al., 2013; LeDoux, 2007; Sah et al., 2003). Most of researchers supported that amygdala could be at least parceled into three separate subregions: centromedial, basolateral, and superficial(Bzdok et al., 2013; Roy et al., 2009). Alongside the superficial nucleus, which presumably engages predominantly in olfactory and probably social information processing, both the medial and lateral amygdala are strongly involved in emotion processing, generation, and regulation(Bzdok et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016; Sah et al., 2003). The lateral amygdala being responsible for fear and reward processing coordinates high-level sensory input, while the medial amygdala emerges as the principal output hub, participating in the top-down regulation of negative emotions and influencing motor movement, visceral responses, and attentional reallocation (Adhikari et al., 2015; Bzdok et al., 2013; Janak & Tye, 2015). Functional coupling between the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and the lateral amygdala is associated with higher use of reappraisal, while coupling between the dlPFC and the medial amygdala correlates with higher use of suppression (Gao et al., 2021). Additionally, the medial prefrontal cortex regulates impulse transmission from the lateral amygdala to the medial amygdala, possibly through GABAergic intercalated cells, thereby controlling the expression of conditioned fear (Quirk et al., 2003). Recent studies have utilized Brainnetome Atlas, which provides detailed information on both anatomical and functional connections, to investigate the functional roles of the medial and lateral amygdala subregions in emotion and emotion regulation(Chen et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2022). In sum, there exists functional segregation among the medial and lateral subregions of the amygdala.

While current research has explored the neural mechanisms underlying the altered mood induced by acute aerobic exercise, the specific role of lateral and medial amygdala in this process has not yet been investigated. Furthermore, existing studies have some limitations such as relatively small sample sizes and gender homogeneity in some cases. Therefore, this study aims to utilize resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI) to investigate the functional connectivity (FC) patterns of the amygdala with other brain regions in a larger and more diverse sample following a moderate-intensity acute aerobic exercise intervention. By comparing FC differences between the basolateral and medial amygdala and other brain regions, this study seeks to elucidate the distinct contributions of these amygdala subregions to the neural mechanisms underlying exercise-induced mood changes.

MethodsParticipantsEighty-three college students aged 18–22 years were recruited for the present study. The minimum sample size was determined using G*Power (Version 3.1) for a repeated-measures ANOVA (2 groups × 2 time points, within-between interaction), with α = 0.05, power = 0.95, and an expected moderate effect size of f = 0.25. This analysis yielded a required minimum of 54 participants (27 per group). The inclusion criteria were: (1) right-handedness (classified via Edinburgh Handedness Inventory(Oldfield, 1971); (2) no history of psychological disorders, psychosis, neurological disorders, or head trauma; (3) no familial background of psychosis; (4) no metal implants or claustrophobia.

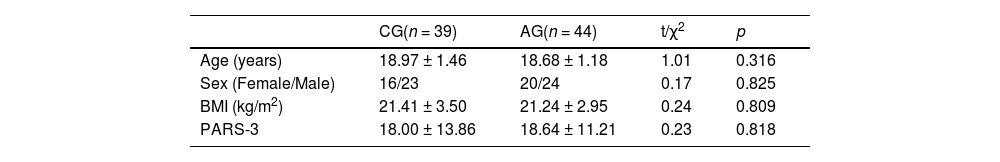

Eligible participants were randomized into an acute aerobic exercise intervention group (AG, n = 44) and a blank control group (CG, n = 39). Notably, there were no significant disparities observed between the groups with respect to age, gender, BMI, and levels of physical activity (Table 1). All data were retained for behavioral analysis. Six participants were excluded due to incomplete or missing imaging data, while one participant was excluded for head movement artifacts. Ultimately, 76 individuals were was subjected to imaging data analysis.

Demographic information of aerobic exercise group and control group.

BMI, body mass index; PARS-3, Physical activity rating scale.

The study protocol was approved by the ethical committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (approval number: H15038). All participants received an explanation of the experimental processes before the study began and provided written informed consent.

MeasurementBasic information questionnaire- (1)

Demographic Information: We collected essential demographic details, encompassing gender, age, academic year, height, and weight.

- (2)

Physical activity rating scale (PARS-3). The 3-item Chinese version(Liang, 1994) of PARS-3(Hashimoto, 1990) was utilized to assess participants' physical activity level based on the frequency, duration, and intensity of their physical activity using a 5-point scale. The overall physical activity score was the product of frequency, duration (minus 1) and intensity. The test–retest reliability of PARS-3 was 0.82(Liang, 1994).

All baseline demographic variables, including gender, age, academic year, and BMI (calculated from height and weight), as well as physical activity level as measured by the PARS-3, were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses.

Emotional measurements- (1)

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). We employed the Chinese version(Huang et al., 2003) of PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) to assess both positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA). The PANAS comprises 20 adjectival descriptors of acute emotional states, with 10 adjectives denoting PA and 10 describing NA. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (very mild) to 5 (very strong). The PANAS has exhibited robust internal consistency reliabilities, with Cronbach's coefficient α values ranging from 0.86 to 0.90 for PA and 0.84 to 0.87 for NA.

- (2)

Abbreviated profile of mood state (A-POMS). The Chinese version(Zhu, 1995) of the 40-item A-POMS (Grove & Prapavessis, 1992) was applied to assess mood states before and after exercise. Derived from the POMS-SF, this scale encompasses seven subscales: “tension”, “depression”, “fatigue”, “vigor”, “confusion”, “anger”, and “esteem-related affect” (reflects feelings of self-worth, confidence, and positive self-evaluation). These subscales can be summed to obtain a “Total Mood Disturbance” (TMD) score, which represents the overall level of negative mood state. All responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). The subscales of A-POMS demonstrated satisfactory reliability, with coefficients ranging from 0.62 to 0.82 (mean = 0.71).

- (1)

Heart rate (HR) monitoring. During exercise and the recovery phase, each participant's HR was monitored using a Polar heart rate monitor (Sport Tester PE 3000, Polar Electro Oy, Finland) at two-minute intervals. To assess exercise intensity, we calculated the age-predicted maximum heart rate (APMHR = 220 - age) for each participant based on their age.

- (2)

Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). The RPE was employed as a subjective measure of exercise intensity, reflecting an individual's perception of their effort level during exercise (Borg, 1998). The RPE scale spans from 6 to 20, with 6 representing "no effort at all" and 20 signifying "maximum effort." For example, a rating of 13 on the RPE scale corresponds to a heart rate of approximately 130 beats per minute, typically indicating moderate-intensity exercise.

Participants were scheduled for a single laboratory visit, during which all experimental procedures were administered over the course of approximately half a day(Ge et al., 2024). Before commencing the study, stringent inclusion criteria were applied, and participants provided informed consent. Subsequently, participants completed the basic information questionnaire. Utilizing random assignment, participants were then allocated to either AG or CG. The study unfolded in three distinct phases: a baseline assessment (pre-test), the aerobic exercise or control intervention, and a concluding assessment (post-test). Both the pre-test and post-test encompassed identical assessments, including emotion assessments and MRI scans, interspersed by a 30-minute exercise intervention or control condition.

The exercise interventions were administered employing a MONARK 834 cycle ergometer (MONARK, Varberg, Sweden). The exercise protocol commenced with a 5-minute warm-up phase, succeeded by 20 min of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise at a controlled work rate and 5-minute cool-down phase. During 20-min exercise phase, the average pedaling rate was maintained at 77 ± 4 rpm. Following the exercise period, a five-minute cool-down phase was implemented, during which participants gradually reduced their pedaling rate and workload to slow down their heart rate and breathing.

The warm-up phase was initiated at a workload corresponding to 60 % of participants' APMHR, approximately yielding a power output of 25 W and a pedaling rate of 50 rpm. The workload was progressively augmented until the exercise intensity reached 60–69 % of the APMHR, as reflected by an average pedaling rate of 77 ± 4 rpm. Throughout the intervention, HR, RPE scales, power output in watts, and revolutions per minute were monitored at 2-minute intervals. After the exercise intervention, participants were instructed to rest until their HR reverted to baseline levels. Only once this criterion was met, the post-test session MRI scan was conducted, ensuring completion within a 10-minute timeframe.

In the control group, participants were tasked with engaging in a 30-minute session of reading neutral textual material without causing mood swings, conducted within a noise-free environment. Throughout this duration, their heart rate was monitored. Notably, the use of cell phones was strictly prohibited during this period.

fMRI data acquisition and analysisAll neuroimaging data were acquired using the Siemens 3T Trio system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The functional images of resting states were obtained using an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence, employing the following scanning parameters: Repetition Time (TR) = 2000 ms, Echo Time (TE) = 30 ms, flip angle (FA) = 90°, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, field of view (FOV) = 200×200 mm2, voxtel-size = 3.4 × 3.4 × 4.0 mm3, 30 axial sections, resulting in a total of 243 brain image data. During the rs-fMRI scan, all participants were instructed to close their eyes, relax, and minimize any movement. High-resolution structural images with a resolution of 1.3 × 1.0 × 1.3 mm were acquired using a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) three-dimensional T1-weighted sequence (TR = 2530 ms, TE = 3.39 ms, FA = 7, slice thickness = 1.33 mm).

For data preprocessing and analysis, the Data Processing & Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI) toolbox was employed (Yan et al., 2016). The preprocessing process includes: (1) converting the data to NIFTI format, (2) discarding the first 10 time points, (3) slice timing correction, (4) motion correction, (5) removal of scalp structures, (6) coregistration of functional images to T1 images, (7) segmentation of images into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, (8) noise and linear drift removal, (9) adjustment of motion parameters using Friston 24, and (10) standardization using DARTEL.

ROIs were selected from the Brainnetome Atlas, a template that divides the entire brain into 246 subregions based on brain structure and connectivity (Fan et al., 2016). In this study, the left medial amygdala, left lateral amygdala, right medial amygdala, and right lateral amygdala were chosen as the four ROIs. Utilizing the DPABI toolbox, functional connectivity (FC) between ROIs and the whole brain voxels was calculated. This involved extracting the average time series for each ROI from individual data and calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) between the ROI time series and the time series of whole brain voxels. The correlation coefficient (r) represents the strength of FC between regions. The obtained correlation coefficients were then transformed using Fisher's r-to-z transformation to obtain normalized functional connectivity.

To specifically assess the impact of the acute exercise intervention on the change in resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC), a whole-brain, voxel-wise mixed-effect analysis was performed for each of the four predefined amygdala subregion ROIs. This analysis was conducted using the mixed-effect analysis module within the DPABI toolbox. For each seed ROI, a model was constructed with FC as the dependent variable. The model included a between-subject factor of Group (Aerobic Exercise vs. Control), a within-subject factor of Time (Pre- vs. Post-intervention), and crucially, the Group × Time interaction term. Our primary analysis focused on the statistical map of this interaction, which identifies brain regions where the change in FC from pre- to post-intervention differed significantly between the two groups. To control for potential artifacts arising from head motion, a critical source of variance in rs-fMRI, the mean Framewise Displacement (FD) value from each scan was included as a time-varying covariate of no interest in the model. The resulting statistical maps for the Group × Time interaction were corrected for multiple comparisons using Gaussian Random Field (GRF) theory. The significance thresholds were set at a voxel-level p < 0.005 and a cluster-level p < 0.05. Significant clusters were visualized using BrainNet Viewer (Xia et al., 2013).

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses for demographic and behavioral data were performed using SPSS (Social Science Statistical Package) version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses unless otherwise specified.

Baseline characteristicsGroup differences in baseline demographics (age, BMI, PARS-3) were tested with independent-sample t-tests; gender with chi-square tests. Baseline mood scores (PANAS, A-POMS) were compared using ANCOVA, with age, gender, BMI, and PARS-3 scores as covariates.

Intervention effects on mood (Behavioral data)Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) assessed Group × Time interactions on mood scores, including age, gender, BMI, and PARS-3 scores as covariates. The GEE model parameters were determined based on model estimation, employing a non-structured working correlation matrix to account for within-subject dependencies. As a sensitivity analysis to further examine the robustness of significant intervention effects on mood, post-intervention mood scores were also analyzed using ANCOVA. In these models, the respective baseline mood score for each dimension, along with age, gender, BMI, and PARS-3 scores, were included as covariates.

Correlation analysesWithin the exercise group (AG), Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to explore the relationship between significant changes in functional connectivity (ΔFC values from brain regions showing significant group differences in the fMRI analysis) and changes in mood scores (ΔMood from PANAS and A-POMS, calculated as post-intervention minus pre-intervention scores).

ResultsBehavioral measurementBaseline data analysis on mood revealed no significant intergroup differences in other emotions except for the positive affect dimension of PANAS and the vigor dimension of A-POMS, where the AG group scored significantly higher than the CG group (see Table S1).

GEE analysis revealed significant time main effects in scores for the NA of PANAS, and all dimensions of A-POMS (Table 2). Group main effects were observed in the PA of PANAS, as well as the vigor, esteem, and TMD dimensions of the POMS scale. Notably, a significant interaction effect was observed in the esteem sub-dimension of the POMS scale (Wald χ² = 4.182, p = 0.041) and TMD total score (Wald χ² = 3.857, p = 0.0497) (Fig. 1). In comparison to the CG group, the AG group exhibited a greater increase in self-esteem related affect and a more pronounced decrease in TMD total scores.

Mood questionnaire scores before and after acute aerobic exercise.

Abbreviations: PA, positive affect; NA, negative affect; TMD, Total Mood Disturbance, the total score of Abbreviated Profile of Mood State scale.

To further validate the robustness of our findings and to account for potential baseline differences that might confound the intervention effects, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a covariance analysis (ANCOVA). In addition to age, gender, BMI, and physical activity level, we included baseline mood scores as covariates in the model to examine the group differences in post-intervention mood scores. The results revealed that the group difference for esteem (F = 4.53, p = 0.037) and TMD total score (F = 4.61, p = 0.035) remained significant even after controlling for baseline mood scores (Table S2). These findings reinforce the robustness of our previous results, suggesting that the observed differences were primarily due to the intervention and not baseline variability.

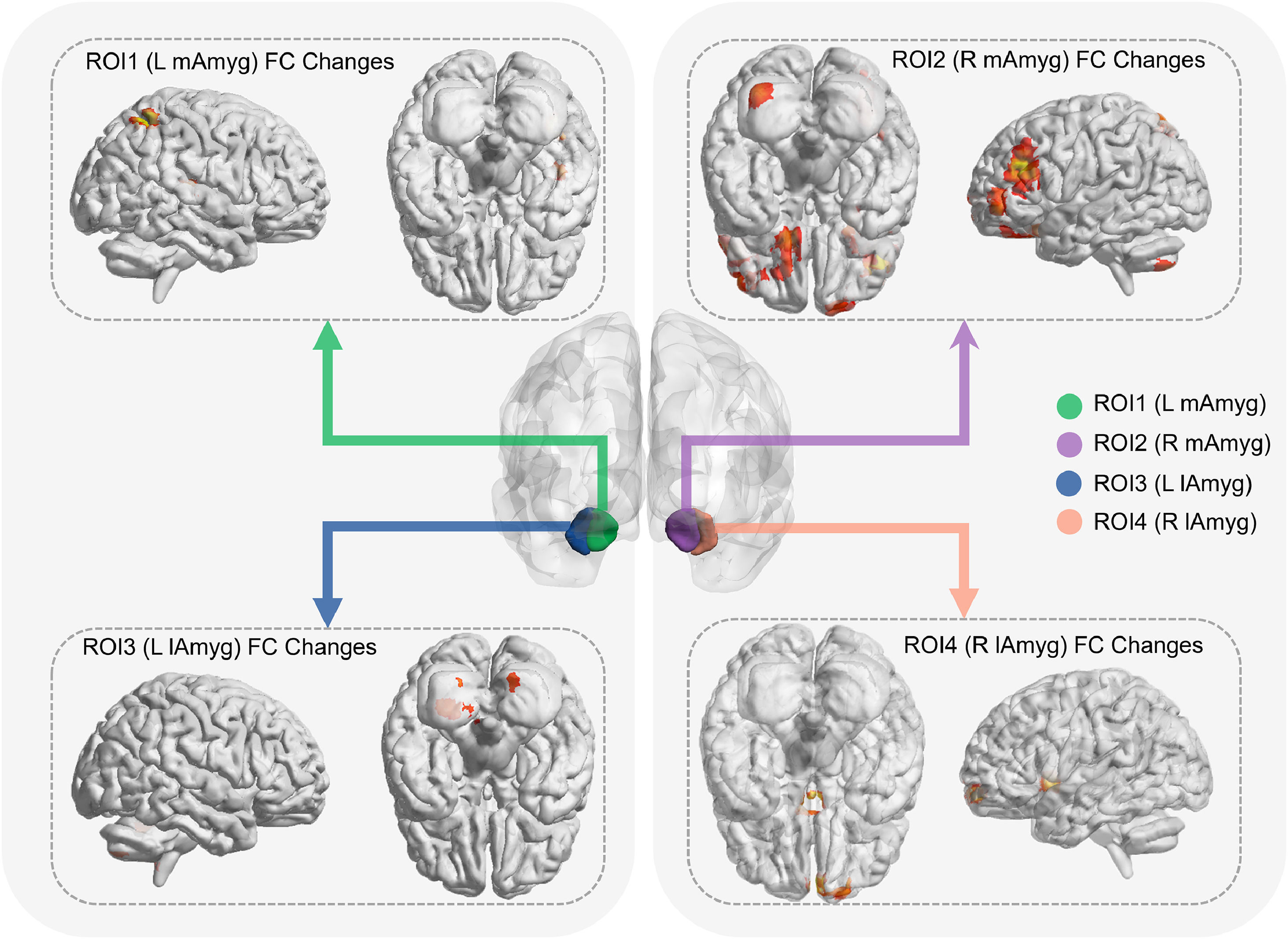

fMRI dataThe whole-brain, ROI-to-voxel analysis revealed significant Group × Time interaction effects on functional connectivity for all four amygdala subregion seeds (See Fig. 2 for visualization and supplementary materials for the full cluster report). This indicated that the exercise intervention differentially modulated amygdala-based network connectivity compared to the control condition.

Effects of acute aerobic exercise on amygdala subregion functional connectivity. The figure illustrates brain regions showing a significant Group (Exercise vs. Control) × Time (Pre- vs. Post-intervention) interaction on resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC), seeded from four distinct amygdala subregions. The central panel shows the four seed ROIs: left medial amygdala (L mAmyg, ROI1), right medial amygdala (R mAmyg, ROI2), left lateral amygdala (L lAmyg, ROI3), and right lateral amygdala (R lAmyg). Arrows indicate the corresponding rs-FC interaction results for each seed, displayed on sagittal and axial views of a standard brain template. Warm colors (red to yellow) represent clusters where the exercise group showed a significantly greater increase in FC compared to the control group. The statistical maps are thresholded at a voxel-level p < 0.005 and a cluster-level p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using Gaussian Random Field (GRF) theory.

Specifically, acute exercise enhanced the left medial amygdala's (mAmyg) connectivity with right superior parietal lobule (SPL) and Heschl's gyrus. For the right mAmyg, the intervention strengthened its FC with multiple large clusters, including the bilateral middle and inferior frontal gyrus, left OFC, left cerebellum (Crus II), right SPL and middle occipital gyrus (MOG). For the left lateral amygdala (lAmyg), we observed significantly increased ∆FC with clusters in the cerebellum (lobules VI, VII, VIII, IX). Finally, the right lateral amygdala (R lAmyg) showed greater increases in ∆FC with the right medial OFC and the left caudate/nucleus accumbens (NAc).

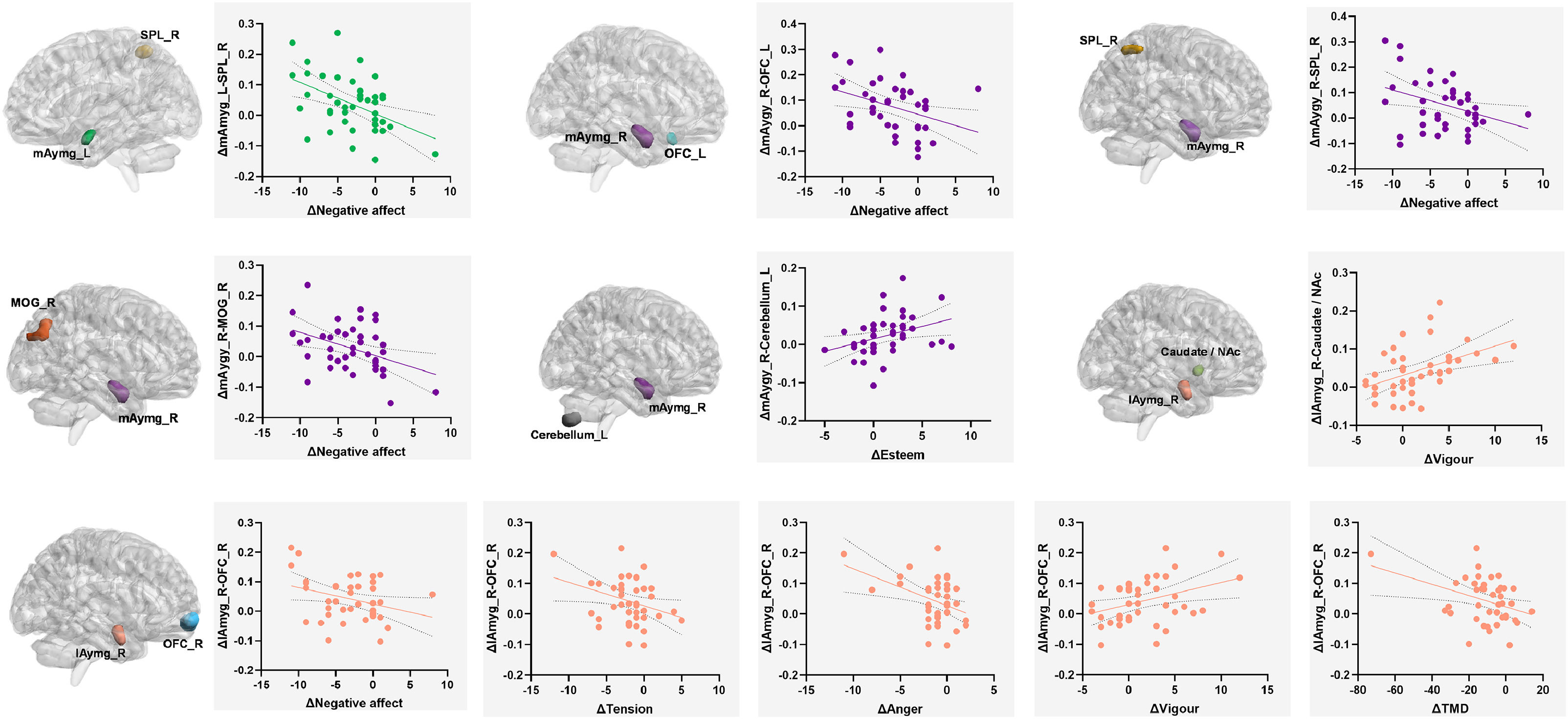

Correlation analysisTo explore the clinical significance of these neural changes, we correlated the ∆FC values with changes in mood scores within the acute aerobic exercise group (Fig. 3).

Correlation analysis of emotional changes and functional connectivity changes in acute aerobic exercise group. Each panel displays a significant correlation found within the aerobic exercise group (n = 44). The left side of each panel shows the seed (e.g., mAmyg_L) and target (e.g., SPL_R) regions of interest for the functional connectivity (FC) pair. The right side shows the corresponding scatter plot. The Y-axis represents the change in FC (∆FC), calculated as the difference in Fisher's z-transformed correlation values (post- minus pre-intervention). The X-axis represents the change in mood scores (∆Mood), calculated as post- minus pre-intervention scores. The solid line indicates the linear regression fit, and the dotted lines represent the 95 % confidence interval of the fit. Abbreviations: mAmyg, medial amygdala; lAmyg, lateral amygdala; SPL_R, right superior parietal lobule; OFC_L, left orbitofrontal cortex; MOG_R, right middle occipital gyrus; NAc, nucleus accumbens; TMD, Total Mood Disturbance.

The enhanced connectivity of the left mAmyg with the right SPL was associated with a greater reduction in Negative Affect (r = −0.459, p = 0.003).

Similarly, enhanced connectivity from the right mAmyg to several regions was also linked to greater reductions in Negative Affect. These regions included the left OFC (r = −0.368, p = 0.018), the right SPL (r = −0.349, p = 0.025), and the right MOG (r = −0.402, p = 0.009). Furthermore, the increased right mAmyg connectivity with the left cerebellum (Crus II) was positively correlated with improved Esteem on the A-POMS scale (r = 0.348, p = 0.026).

The right lAmyg showed associations with a particularly diverse range of mood dimensions. Enhanced connectivity between the right lAmyg and the right OFC was related to decreases across four negative indices: Negative Affect (r = −0.315, p = 0.045), Tension (r = −0.319, p = 0.042), Anger (r = −0.408, p = 0.008), and the Total Mood Disturbance (TMD) score (r = −0.368, p = 0.018). The same right lAmyg-OFC connection was also positively associated with increased Vigour (r = 0.367, p = 0.018). Additionally, the right lAmyg's enhanced connectivity with the caudate/nucleus accumbens showed another strong positive correlation with increased Vigour (r = 0.448, p = 0.003).

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate the distinct roles of amygdala subregions in mood improvements following a single bout of acute aerobic exercise in a large sample of young adults (the published database: doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.14222 (Ge et al., 2023)). The results not only validated previous findings (Ge et al., 2021), but also significantly extend this work. We revealed a key functional dissociation between amygdala subregions. Furthermore, these neuroplastic changes showed a notable right-hemisphere lateralization. Behaviorally, the exercise intervention led to significant improvements in mood, most notably an increase in self-esteem and a decrease in total mood disturbance. These emotional benefits were correlated with extensive changes in functional connectivity originating from both the right medial and right lateral amygdala. The right mAmyg enhanced its connectivity with cortical and cerebellar regions, which was linked to both reduced negative affect and improved self-esteem. Concurrently, the right lAmyg strengthened its pathways to the OFC and striatum. This network was associated with a particularly broad spectrum of emotional benefits, as it related to the alleviation of multiple negative states, such as anger and tension, alongside an increase in vigour. Collectively, these results offer direct neurobiological evidence for the nuanced and lateralized roles of amygdala subregions in exercise-induced emotion regulation and suggest potential new targets for therapeutic interventions.

Firstly, this study has uncovered the critical role of right amygdala-OFC circuits in mediating the mood-enhancing effects of exercise, revealing distinct contributions from medial and lateral subregions. The observed enhancement of amygdala-OFC connectivity is broadly in line with previous work (Ge et al., 2021) and supports the OFC's established role in the automatic, uninstructed regulation of negative emotions (Phillips et al., 2008; Silvers et al., 2015). This process is thought to involve the OFC modulating the internal processing of the amygdala (Ghashghaei & Barbas, 2002), thereby strengthening top-down emotional control. Our results suggest that acute exercise facilitates this crucial regulatory mechanism. Specifically, we found that enhanced connectivity between the right mAmyg and the left OFC was associated with reduced Negative Affect. This may reflect the fundamental process of down-regulating general negative feeling states. Moreover, the enhanced connectivity between the right lAmyg and the right OFC appears to function as a pivotal pathway for comprehensive emotional recalibration. This single pathway was linked not only to reduced Negative Affect, tension, anger and overall Total Mood Disturbance, but also a concurrent increase in vigor. These findings can be understood within the framework of dual-mode theories, which posit that emotional responses to exercise arise from continuous interactions between cognitive factors (e.g., prefrontal regulation) and interoceptive signals (Tempest & Parfitt, 2017). By strengthening the amygdala-OFC pathways, exercise may enhance the ability to down-regulate negative emotions generated by aversive internal or external cues (Lee et al., 2012; Ochsner et al., 2012). This strengthening of prefrontal-amygdala regulation, occurring without conscious instruction, provides strong evidence for an “automatic regulatory mechanism” at play. The association with increased vigor, in particular, points towards the engagement of the brain's core motivation and reward systems

A notable finding of this study was the elucidation of the neural mechanisms underlying the increase in exercise-induced vigor. Vigor is conceptualized not merely as a simple positive mood, but as a multifaceted state of positive arousal encompassing feelings of physical strength, emotional energy, and cognitive liveliness (Shirom, 2011). Our findings compellingly map this rich psychological construct onto key nodes of the brain's core motivation and reward systems (Balleine & O'Doherty, 2010; Haber & Knutson, 2010). We found that enhanced connectivity between the right lAmyg and both the striatum (caudate / NAc) and the right OFC was strongly correlated with increased vigor. The involvement of the striatum is particularly telling. The caudate is a key node in translating motivation into goal-directed action, a process heavily modulated by mesolimbic dopamine which is known to energize behavior rather than simply mediate pleasure (Balleine & O'Doherty, 2010; Salamone & Correa, 2012). Our right lAmyg-caudate finding thus suggests a powerful mechanism: acute exercise may boost subjective vitality by strengthening the communication between the amygdala's assessment of the body's positive, energized state and the striatal system that drives motivated action. Concurrently, the right lAmyg-OFC pathway's association with vigor likely reflects an enhanced representation of the rewarding value of this high-arousal state. This aligns with the OFC's essential role in computing the subjective value of experiences to guide decisions (Kringelbach, 2005; Rolls, 2019). Together, it appears that exercise enhances vigor by engaging parallel pathways that not only increase the rewarding valuation of the post-exercise state via the OFC, but also facilitate the translation of this motivation into a state of action readiness via the striatum.

This study also revealed that acute aerobic exercise led to enhanced FC between the bilateral medial amygdala and the right SPL. And this enhancement was associated with decreases in negative emotion. The SPL are generally associated with functions such as selective attention and working memory, and the control network and dorsal attention network containing it play roles in reallocating attention during emotion regulation and emotion control (Ochsner et al., 2012). Following exercise intervention, the right SPL was more activated (Huang et al., 2021), and there was enhanced FC between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the SPL (Prehn et al., 2019). This is supported by a range of evidence, from mindfulness studies showing reduced anxiety via parietal activation (Goldin et al., 2013), to ERP studies demonstrating enhanced attentional resource allocation after exercise (Qiu et al., 2019). Notably, both the amygdala and the SPL are involved in emotion processing and regulation. For instance, a study comparing brain function in healthy individuals and those with generalized anxiety disorder revealed a reduced FC between the amygdala and the SPL in the latter group when observing fearful faces, indicating that disrupted FC between these two regions might result in impaired emotion processing and social functional behaviors (Mukherjee et al., 2012). Taken together, the evidence suggests that exercise enhances the FC between the amygdala and the SPL, reallocates attention resources, enhances cognitive flexibility, and thereby regulates negative emotions and anxiety. Furthermore, the attention diversion hypothesis of exercise-induced emotional improvement posits that acute exercise can divert participants' attention away from negative thoughts, potentially being a primary mechanism for emotional improvement (Mikkelsen et al., 2017).

Our study found that acute exercise significantly enhanced self-esteem, a key behavioral outcome that aligns with a large body of research showing the capacity of exercise to bolster positive affective states (Ekeland et al., 2005; Park et al., 2014; Scully et al., 1998). This dimension of the POMS scale represents a state of pride and satisfaction that reflects an individual's positive self-appraisal (Grove & Prapavessis, 1992; Sonstroem & Morgan, 1989). We provide a specific neural substrate for this psychological benefit, revealing that the enhancement in self-esteem was directly correlated with increased functional connectivity between the right mAmyg and the left cerebellum (Crus II). This finding contributes significantly to the growing understanding of the cerebellum's role in high-order affective functions, far beyond its traditional association with motor control (Strata, 2015). This result provides specific evidence for a cerebellar pathway involved in modulating higher-order, self-evaluative emotions. It aligns perfectly with meta-analyses indicating a specialized function for the cerebellar Crus II lobule in self-experiencing emotions (Van Overwalle et al., 2020), and studies showing cerebellar activation during the induction of positive emotions (Habel et al., 2005; Matsunaga et al., 2009). The neuroanatomical basis for such a connection is well-supported by bidirectional pathways between the cerebellum and limbic structures, suggesting a tightly integrated regulatory loop (Sacchetti et al., 2005; Taub & Mintz, 2010). The clinical relevance of this circuit is highlighted by findings that its disruption is linked to impaired emotion processing in conditions like generalized anxiety disorder (Liu et al., 2015). Crucially, our connectivity-based finding resonates with recent research demonstrating that exercise itself can enhance cerebellar activation to regulate emotion (Kommula et al., 2023) and alleviate anxiety through specific cerebellum-amygdala pathways (Spaeth & Khodakhah, 2024; Zhang et al., 2024). Furthermore, our finding of a right amygdala to left cerebellum connection is consistent with neuroimaging studies on the lateralization of emotional functions, which associate positive emotions more with the left cerebellar hemisphere (Sang et al., 2012). The psychological mechanism linking the successful completion of exercise to self-esteem can be explained by the self-efficacy hypothesis, where successfully completing a challenging task fosters a sense of mastery and positive self-evaluation (Mikkelsen et al., 2017; Sonstroem & Morgan, 1989; Tang, 2000). It is plausible that the enhanced right mAmyg-left Cerebellum Crus II connectivity is the neural underpinning of this process, reflecting how the brain translates the rewarding experience of physical accomplishment into an improved sense of self-worth. This strengthening of a key pathway for processing positive, self-related affective states may also contribute to enhanced interoception and broader emotion regulation abilities (Du et al., 2023; Smith et al., 2022). Interestingly, we also found that exercise strengthened the connectivity of the left lAmyg with other cerebellar lobules, although this was not directly correlated with our measured mood outcomes. This suggests that acute exercise may broadly engage multiple, distinct cerebellar-amygdala circuits, whose specific functional roles represent a rich area for future investigation.

A striking pattern that emerged from our findings is the pronounced right-hemisphere lateralization of exercise-induced changes in amygdala connectivity. While we observed significant effects originating from both left and right subregions, the most extensive and diverse associations with mood improvement were linked to the right medial and right lateral amygdala. This observation aligns with a body of literature suggesting a specialized role for the right amygdala in the processing of emotionally salient stimuli and the automatic generation of affective states (Cho et al., 2018; Sergerie et al., 2008). Previous research has documented that neural activity and even structural volume in the right amygdala tend to be greater than in the left (Ball et al., 2007; Roy et al., 2009), potentially underlying its role in faster habituation and more automatic emotional reactions. Our findings extend this concept from general activity to exercise-induced network plasticity. While other studies have shown exercise-induced FC changes involving a non-lateralized amygdala(Chen et al., 2019; Schmitt et al., 2020), our subregion-specific approach allows us to postulate that the right amygdala, encompassing both its medial and lateral components, is particularly pivotal in orchestrating the immediate mood-enhancing effects of physical activity.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations in this study. Firstly, the current investigation only examined the effects of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on emotions. Previous research has indicated that high-intensity exercise might have a more pronounced impact on emotion improvement, particularly in individuals with high levels of anxiety (Broman-Fulks et al., 2004; Henriksson et al., 2022; Knapen et al., 2009). Hence, future studies might explore a wider spectrum of exercise intensities to delineate their specific emotional effects. Secondly, while this study observed improvements in self-esteem emotion and speculated a link to changes in self-efficacy, direct assessments of self-efficacy were not incorporated into the research design. Future research aiming to delve into the psychological mechanisms behind the improvement of self-esteem through exercise could incorporate assessments of self-efficacy. Thirdly, subgroup analyses were not conducted in this study, leaving room for future investigation into individual differences in the emotional benefits derived from exercise. Fourthly, prior studies have shown that acute exercise can enhance cognitive functions like attention, working memory, and inhibitory control by modulating brain activity in regions such as the prefrontal cortex and parietal lobe. This suggests that the mood improvements from acute exercise may be partly mediated by cognitive enhancements. Future research could explore the interplay between these cognitive and emotional benefits (Chang et al., 2015; Chu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2014). Fifthly, the spatial resolution of the rs-fMRI sequence used in this study may limit the ability to accurately assess functional connectivity within the amygdala subregions. Future work could benefit from employing higher spatial resolution imaging techniques or smaller field-of-view acquisitions to improve the precision of such analyses. Lastly, while our focused seed-based analysis of the amygdala yielded significant insights, future work employing broader brain network analyses could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the neural underpinnings of exercise-induced emotional changes.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study provides compelling evidence that acute aerobic exercise improves mood by engaging distinct and lateralized neural circuits centered on different amygdala subregions. Our findings converge on a unifying theme: acute aerobic exercise appears to function as a potent form of automatic emotion regulation. This form of regulation, as delineated by I. Mauss and colleagues (2007), modifies emotion without conscious deliberation. The rapid mood improvements observed in our study fit this definition perfectly, and our neurobiological results offer a plausible, multi-pronged neural architecture for how this automatic recalibration is achieved.

Specifically, we identified several potential pathways underlying these benefits. These include: (1) enhanced top-down regulation of negative affect via OFC-amygdala circuits; (2) improved attentional resource allocation through parietal-amygdala pathways; (3) modulation of self-evaluative emotions like self-esteem via cerebellar-amygdala connections; and (4) a boost in motivation and reward processing related to feelings of vigor through striatal-amygdala pathways.

Future research should further validate the roles of these distinct processes in exercise-induced mood improvement. It is essential to explore the interplay between top-down automatic emotion regulation, attentional shifting, self-evaluation, and the motivational effects of engaging the brain's reward circuitry. Understanding how these specific amygdala-based pathways contribute to well-being will be crucial for developing more targeted and effective exercise-based interventions for emotional disorders.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32471133), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central public welfare research institutes (RXRC2022005), the Key Program of National Social Science Foundation of China (24ATY009), STI 2030-Major Projects 2021ZD0200500, and the student mental health research project of the National Center for Mental Health, China.