Edited by: Dr. Sergi Bermúdez i Badia

(University of Madeira, Funchal, , Portugal)

Dr. Alice Chirico

(No Organisation - Home based - 0595549)

Dr. Andrea Gaggioli

(Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milano,Italy)

Prof. Dr. Ana Lúcia Faria

(University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal)

Last update: December 2025

More infoInterpersonal synchrony (IPS), the temporal alignment of behaviors between individuals, fosters social bonding, cooperation, and sharing in children. These prosocial outcomes make IPS a promising mechanism to support social inclusion and psychological well-being, particularly in therapeutic and educational contexts where strengthening peer interaction is essential. However, most IPS interventions rely on static dyadic tasks that lack playfulness and ecological validity, limiting their generalization to real-world environments. Advances in Mixed Reality (MR) offer new possibilities for designing more natural and embodied IPS experiences. Nevertheless, it remains unclear which specific design elements are most effective in eliciting synchrony that fosters prosocial outcomes in group-based settings. This study introduces The Moving Mandala, a playful Mixed Reality experience designed to foster real-time synchrony among four children (ages 8–10) through audiovisual cues and embodied interaction. In a between-subjects study with 268 children, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: “no prior movement” (Baseline), “asynchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Control), “synchronous and rhythmic music” (Experimental 1), and “synchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Experimental 2). The study tested: (i) whether rhythmic auditory stimuli enhance IPS compared to non-rhythmic ambient sound, and (ii) whether synchronous movements facilitate prosocial behavior and social bonding compared to asynchronous and no prior (baseline) movements. Results showed that rhythmic music significantly improved synchrony performance, confirming its role as a temporal scaffold. However, no significant differences in prosocial behavior or social bonding were found between conditions. Design choices such as limited mutual dependency and high cognitive load may have reduced the salience of interpersonal cues. These findings highlight both the potential and challenges of using MR to promote synchrony-based social outcomes. By identifying key design elements, this work contributes to the development of engaging socially supportive MR interventions for children, with potential applications in therapeutic, educational, and rehabilitative contexts.

Positive social interaction in childhood is essential for healthy development, fostering emotional well-being, supportive peer relationships, and long-term social inclusion (Rao et al., 2008). However, not all children have equal access to these experiences. Children with neurodevelopmental differences, such as those on the Autism Spectrum, may face specific difficulties in social communication and social interaction that can lead to peer rejection and bullying (Kloosterman et al., 2013), hindering both personal and academic growth (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000). This underscores the need for society to actively address these disparities by creating environments that promote equitable and meaningful social engagement, ensuring that children with and without disabilities are motivated to interact and can overcome developmental barriers. Such inclusive approaches are essential to support all children in achieving satisfying developmental trajectories.

New technologies emerge as potential tools for reducing barriers to social interaction and fostering inclusive experiences (Center for Universal Design, 1997). They support the design of dynamic environments tailored to a wide range of users, enhancing accessibility and enabling personalized engagement (Boucenna et al., 2014; Porayska-Pomsta et al., 2012). Beyond broadening access, they also improve the quality of social and learning experiences (Boucenna et al., 2014; Heng et al., 2021), contributing to more equitable and welcoming spaces.

Building on this potential, the Child-Computer Interaction (CCI) field has increasingly focused on designing interactive experiences that promote collaboration and cooperation. These are foundational skills for supporting meaningful social interaction (Baykal et al., 2020), particularly among children with special needs (Boucenna et al., 2014; Heng et al., 2021). The benefits of using interactive technologies are that they provide opportunities for children to participate in joint activities, practice social skills, and collaborate in ways that are often not possible in traditional settings (Bernardini et al., 2014; Gali-Perez et al., 2021; Garzotto et al., 2020; Keay-Bright, 2009; Parés et al., 2006). By offering real-time feedback, adapting to individual needs, and supporting playful and multisensory interaction, CCI fosters active engagement and stronger interpersonal connections. However, the development of these skills depends on interactive designs that enforce or encourage such interactions (Battocchi et al., 2010; Crowell et al., 2019; Millen et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2023). This opens new research opportunities to explore interaction designs that promote voluntary and spontaneous cooperation and social bonding in child-centered play environments.

To address this research gap, the present study builds on the hypothesis that by first fostering a positive social interaction environment, social behaviors will emerge more naturally and be sustained by intrinsic motivation. In turn, this may lead to more frequent social interactions and better generalization to real-life contexts. To support this, we investigated how Interpersonal Synchrony (IPS) can be used to create more open and engaging social contexts. This phenomenon involves the synchronization of actions between two or more organisms to a common rhythm, emphasizing the critical element of time alignment (Cross et al., 2019; Rinott & Tractinsky, 2022). Unlike mimicry, it does not require defined leader–follower roles (Bente & Novotny, 2020) and emerges through a process of entrainment, which is the temporal adaptation between interacting systems (Bernieri & Rosenthal, 1991). Entrainment can be intentional or unintentional (Cross et al., 2019; Koban et al., 2019). Unintentional synchronization arises without conscious awareness, as when individuals unconsciously align their walking pace (motor synchrony) (Koban et al., 2019), or when physiological (e.g., interbeat intervals) or neural systems align (physiological and neural entrainment, respectively) (Gordon et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2020; Trost et al., 2017). In contrast, intentional motor synchrony occurs when individuals deliberately coordinate their movements. This study focuses on this latter form, commonly referred to as Interpersonal Synchrony, also described in the literature as Interpersonal Entrainment or Interpersonal Movement Synchrony.

As a non-verbal communication mechanism, IPS has demonstrated positive effects on early development (Cirelli, 2018) and has shown an increase in social bonding (Howard et al., 2021; Rabinowitch & Knafo-Noam, 2015; Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016), helping (Cirelli et al., 2014; Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010; Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2018), cooperation (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010; Rabinowitch & Meltzoff, 2017b), and sharing with co-actors (Rabinowitch & Meltzoff, 2017a); attitudes identified as prosocial behaviors (PBs) (Cross et al., 2019; Dunfield et al., 2011). Despite its promise, IPS is often studied in controlled laboratory settings through repetitive hand movements in fixed positions (e.g., clapping, drumming), without exploring more complex movement dynamics. In a few cases, such as in Kirschner and Tomasello (2010), where the activity was more dynamic, the researcher's intervention was required to guide the children. This traditional focus on simple movements limits the richness of interaction and fails to capture the complexity of synchrony in everyday situations. Furthermore, these approaches are typically restricted to dyadic interactions and are rarely embedded in playful contexts, making them less representative of children's spontaneous and dynamic social behaviors. In addition, static tasks limit physical engagement, reducing both motivation and the sensorimotor benefits of active participation (Wilson, 2002). These limitations underscore the need for IPS interventions that are dynamic, playful, adaptable, and that support group interactions without relying on adult facilitation to promote prosocial behavior in children.

These challenges can be addressed through the use of Interactive Immersive Technologies, particularly through full-body interactive experiences grounded in the principles of Embodied Cognition (Dourish, 2001). This theory states that the cognitive process cannot be understood separately or independently from bodily capacities such as perception and movement (Wilson, 2002). Therefore, these systems (Cibrian et al., 2017; Gali et al., 2024; Ragone et al., 2020; Takahashi et al., 2018) enable the design of ecologically valid and engaging activities that promote synchrony by engaging multiple children in shared bodily experiences integrating perception, movement, and social interaction. By aligning actions in real-time, it creates conditions that could naturally enhance social bonding and prosocial tendencies. Among these technologies, Mixed Reality (MR) stands out for its capacity to combine embodied movement, multisensory stimuli, and face-to-face interaction in shared physical spaces between multiple players. An example is the MR environment developed by Takahashi et al. (2018), which uses visual cues to synchronize the full-body movements of four children with special needs through an immersive group experience. In this paper, we define MR following the continuum proposed by Milgram et al. (1995), and further refined by Speicher et al. (2019), as a medium in which users interact simultaneously with both physical and virtual environments, rather than navigating exclusively within fully virtual environments detached from the real world, such as those based on Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) or CAVE-like systems (Cruz-Neira et al., 1992). Considering Speicher et al's. (2019) classification criteria (number of environments, number of users, level of immersion, level of virtuality, and degree of interaction), the MR used in our study blends a real-world space with an interactive virtual environment, allowing four users to engage simultaneously and explicitly with virtual elements through full-body interaction, without compromising face-to-face communication and social presence.

Building on the potential of these systems, the present study introduces The Moving Mandala, a full-body Mixed Reality experience designed to support real-time synchrony among four users in a fluid, natural, and engaging manner. Developed through an iterative design process and informed by the validation of a pre-interactive prototype defined by Cross et al. (2025); Gali et al. (2023), the experience fosters face-to-face interaction through intuitive audiovisual cues and full-body movement. Beyond addressing the limitations of traditional IPS interventions, this project aims to inform the design of embodied technological environments that foster social well-being. It aims to identify the elements that most effectively facilitate synchrony and prosocial behaviors. Specifically, we investigated the role of rhythmic versus non-rhythmic auditory stimuli in facilitating IPS, based on the premise that rhythmic input enhances synchrony by aligning with individuals’ natural tendency to follow musical tempo (Bente & Novotny, 2020). To this end, in a between-subjects study, participants were randomly assigned to one of four conditions: “no prior movement” (Baseline), “asynchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Control), “synchronous and rhythmic music” (Experimental 1), and “synchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Experimental 2). The study pursues two main objectives: (i) compare the effects of rhythmic and non-rhythmic auditory stimuli on task performance, as an indicator of IPS facilitation; and (ii) evaluate whether engaging in synchronous movements (experimental conditions), compared to asynchronous (control condition) and no prior movement (baseline condition), increases prosocial behavior and social bonding in children. Accordingly, we hypothesize that:

- •

Hypothesis 1. Children engaging in synchronous movements accompanied by rhythmic music (Experimental 1 condition) will show enhanced task performance and, consequently, greater synchrony compared to those exposed to ambient non-rhythmic music stimuli (Experimental 2 condition). Consequently, it is expected that:

- ○

Hypothesis 1.1. Children will exhibit a higher frequency of particle activations in the synchrony condition with rhythmic music (Experimental 1 condition) compared to the synchrony condition with non-rhythmic ambient music (Experimental 2 condition).

- ○

Hypothesis 1.2. Children’s perception of the helpfulness of music in guiding actions will be higher in conditions with rhythmic music background (Experimental 1 condition) compared to those with non-rhythmic ambient music (Experimental 2 condition).

- ○

- •

Hypothesis 2. Children participating in synchronous movements (Experimental conditions) will exhibit higher levels of prosocial behavior and social bonding compared to those in asynchronous (Control condition) or no prior movements (Baseline condition). Specifically, we expect that:

- ○

Hypothesis 2.1. Affiliation scores, assessed through the items feeling part of a team and liking the other participants as indicators of social bonding, are expected to show a greater increase from pre- to post-participation in the synchronous movements (Experimental conditions) compared to the asynchronous movements (Control condition). In the absence of a significant difference, we hypothesize a significant within-condition increase in perceived affiliation (liking the others and feeling part of a team) from pre- to post-intervention.

- ○

Hypothesis 2.2. Children will share more resources with their peers following synchronous movements (Experimental conditions) than after asynchronous (Control condition) and not previous (Baseline condition) movements.

- ○

Hypothesis 2.3. Children will physically position themselves closer to their peers following synchronous movements (Experimental conditions) than after asynchronous (Control condition) and not previous (Baseline condition) movements.

- ○

By embedding IPS techniques within an immersive environment, this study aims to contribute to the development of eXtended Reality (XR)-based interventions that support social interaction, inclusion, and psychological well-being.

MethodsThis section describes our research methodology, including the study design, participant details, the full-body Mixed Reality experience description, the objective and subjective measures, and the study procedure.

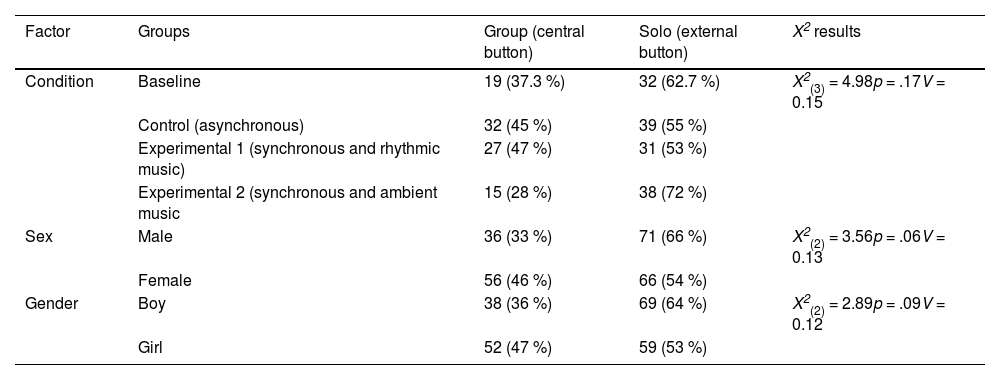

Study design and participantsThe sessions were conducted at the Full-Body Interaction Lab facilities (Barcelona, Spain), involving sixteen classes of third and fourth-grade students (N = 336 children), aged 8–10 years old. The children participated as part of a school activity during regular class hours. Each class group was assigned a specific day for their session, previously agreed upon with the school, and accommodating a maximum of 25 children per trial. As in previous studies (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010), children were familiar with each other to recreate a situation analogous to traditional small-scale societies. Each session comprised subgroups of four children, with neither sex nor gender being a determining factor in the grouping. However, except for a single subgroup consisting solely of females, none of the subgroups exclusively comprised children of a single sex or gender, resembling real-life mixed sex/gender groups. To reduce the risk of interpersonal bias in prosocial behavior outcomes, subgroup formation was carried out with the assistance of each group class's tutor. Random assignment was avoided to prevent placing children with strong positive or negative affinities in the same subgroups, as relationships could significantly influence the prosocial and social bonding outcomes. From the total sample, 68 children were excluded due to (i) one or more children in the subgroup having a medical diagnosis presenting cognitive and/or social interaction difficulties (17 children were directly affected; resulting in the exclusion of their full subgroups, excluding a total of 43 children from the analysis); (ii) the subgroup not being composed of four children (5 children); or (iii) tracking system issues (20 children). A final sample of 268 children was included in the study. Each subgroup was randomly assigned to one of the four conditions: “no prior movement” (Baseline condition), “asynchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Control condition), “synchronous and rhythmic music” (Experimental 1 condition), and “synchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music” (Experimental 2 condition). The study employed a between-subjects design. The demographics of each condition are detailed in Table 1. The children participating in the study were not explicitly informed about the experimental objective; instead, they were informed that they would be evaluating a new video game and providing their opinions on it.

Demographic profile of participants.

The research was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Committee for Ethical Review of Projects of Pompeu Fabra University (protocol code: 229; date of approval: 25 October 2021). The research protocol was reviewed and validated before data collection. The study was not pre-registered in a public repository. We gathered written informed consent forms from legal representatives before the sessions and obtained oral assent from the children on the day they participated. Participants were free to withdraw at any time without penalty and measures were taken to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. The game-based nature of the MR experience ensured a child-friendly and engaging environment without inducing stress or discomfort.

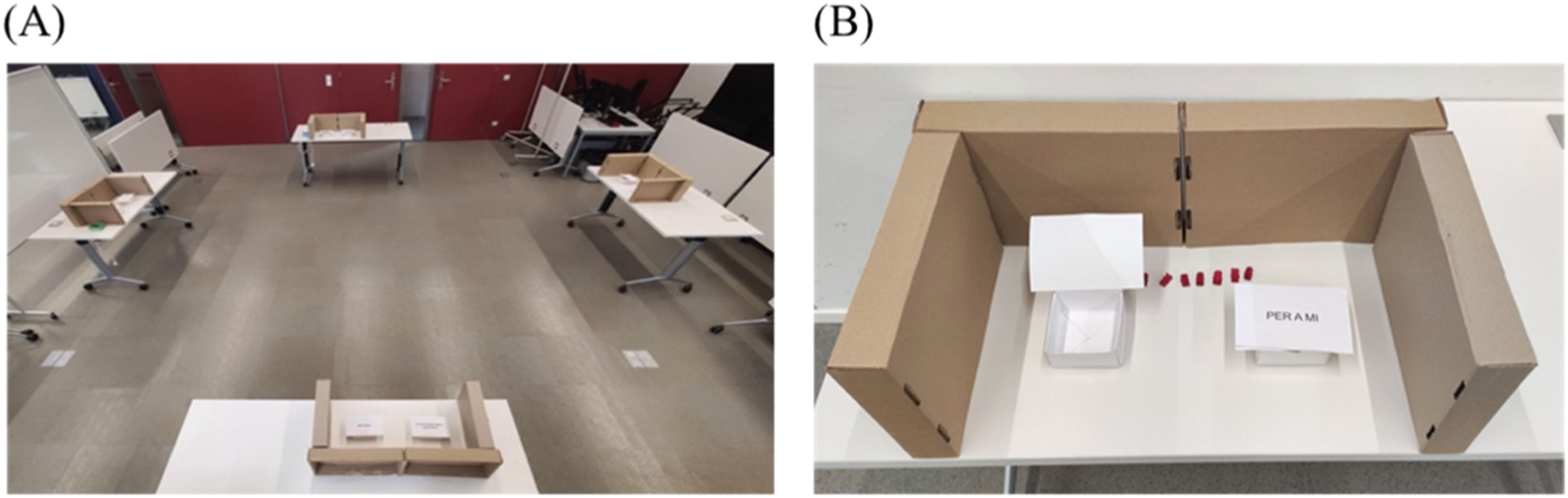

Full-body mixed reality experience: the Moving MandalaPhysical configuration. It comprises a graphic workstation, two overhead HD projectors generating a 1920 × 1920 pixels projection on a 6 × 6 m surface, and a HiFi spatially-panned sound system (Fig. 1A). The setup is designed to support face-to-face non-invasive experiences, meaning that no head-mounted displays or body-worn sensors are required. This eliminates technological barriers often present in Virtual or Augmented Reality systems, offering users an unobstructed view of each other and enabling full use of non-verbal communication cues.

Tracking system. It is an in-house computer vision-based tracking system employing four colour cameras, positioned at the north, south, east, and west sides of the interaction space (Fig. 1A), to detect and track four luminous interactive objects based on their RGB values. The viewing range of the cameras covered 1/2 of the interaction surface, each one rotated 90° with respect to its neighbor cameras. This offered redundancy from the cameras to improve robustness and precision. The tracking system communicated with the Unity full-body experience by using UDP protocol. The system was developed in C++ using OpenCV libraries and had been successfully implemented in other research projects (Gali et al., 2024; Mora-Guiard et al., 2016) involving full-body interaction, demonstrating its technical viability and reliability for real-time tracking in collaborative mixed reality environments. The system demonstrated a precision of approximately 4 cm, as validated by aligning the projected environments with physical space measurements on the floor. Since our full-body interaction experiences are based on gross motor control, this precision is sufficient to measure the activity of users within a 6 × 6 m area. Even more so when the interactive object that we developed was a handheld circular physical object, 20 cm in diameter and battery-powered, with LED lights around its perimeter (Fig. 1B). Each child was assigned a different color: red, green, blue, and purple.

Mixed Reality experience. The shared goal is to build a Mandala (abstract geometric design/pattern, see Fig. 2 for the pattern used), consisting of four phases: (1) demonstration; (2) familiarization with the environment and co-actors; (3) joint activity (familiarization with the mechanics and main game); and (4) experience closure. The system was developed in Unity and C# through an iterative design process. It builds upon a pre-interactive prototype validated by Cross et al. (2025); Gali et al. (2023). The following describes the final version of the experience as designed and implemented for the study.

The Moving Mandala experience: (A) Familiarization with the environment and the co-actors phase; (B) Structure to create the Mandala during the joint activity; (C) Final Mandala created at the end of the experience; (D) Experience mediating the actions of four children to synchronize their movements (experimental condition).

Demonstration. Before starting the interactive activity, children watch a laptop video demonstrating the movement sequence with the interactive object (see Supplementary Video - Demonstration). Following the video's example, they are invited to replicate the movements shown, as in Tunçgenç and Cohen (2016). This phase lasts 5–6 min approximately.

Familiarization with the environment and co-actors. The experience begins with participants standing on footprints in the center of the interactive space, facing outward (Fig. 2A). Once detected, a visual and auditory cue confirms their position. After an initial interaction with the system, a group of particles (glitter cloud) appears, guiding them toward the corners (dubbed stations). In this new position, they face the center, allowing them to observe their peers. This 35-second familiarization phase introduces movement mechanics, system interaction, and group awareness.

Joint activity. Once all participants are positioned at their designated stations, a set of regularly arranged dots appears in the center, outlining the Mandala structure to be created (Fig. 2B). At each station, children see three empty circles in front of them (left, front, right) where a glitter cloud appears in sequence. They are instructed to touch the glitter clouds using the interactive object held with both hands, moving it from their position toward the appearing cloud in a back-and-forth motion. If activated, the glitter cloud transforms into a glitter river, flowing toward the Mandala's center and contributing to its colorful construction (Fig. 2C-D). If not activated, the glitter cloud disappears after one second. To maintain engagement, users transition counterclockwise to a new station after a set number of interactions, fostering a joint transition. To avoid frustration and ensure that all participants experience a sense of achievement, any Mandala layer left incomplete due to missed glitter cloud activations during the three-circle cycle is automatically completed during this transition. This design choice was intended to sustain motivation and ensure that all children reach the end of the experience with a visually complete and rewarding outcome. During these transitions, they follow a glitter cloud that expands upon activation, reinforcing movement toward the next station. Once they arrive, the three-circle cycle restarts. The experience includes eight rounds, with the number of required interactions before transitioning gradually decreasing to sustain dynamism and progressive adaptation to the mechanics while allowing enough time for participants to experience interpersonal synchrony, considered key to fostering prosocial behavior (see Table 2). The Mandala's color remained consistent across all players in each round, alternating between yellow, blue, and orange. More details on the design rationale are available in Supplementary Material – Design Details.

The experience was designed to support three of the four conditions included in this study, excluding the baseline (no prior movement) condition, which varied in movement synchronization and auditory feedback:

- 1.

Experimental 1 (synchronous and rhythmic music). The glitter cloud appears for all users in sequence at four-second intervals (left, front, right, front), meaning all four players interact simultaneously (Fig. 3A). This condition is accompanied by a custom-composed rhythmic track (C Major, 120 bpm, 4/4 time signature), featuring bass, piano, body percussion (claps), drums, guitar, and synth pads. More details on the music are available in Supplementary Material – Design Details. Each user completes 61 interactions in total.

- 2.

Experimental 2 (synchronous and ambient non-rhythmic music). Identical to Experimental 1 (Fig. 3A) but using a non-rhythmic ambient version of the same composition, with the rhythmic structure removed (refer to Supplementary Material – Design Details).

- 3.

Control (asynchronous and ambient non-rhythmic music). The glitter cloud appears at different times for each user in the left-front-right sequence, ensuring there are never two or more children interacting simultaneously (Fig. 3B). This condition is also accompanied by non-rhythmic ambient music. To ensure that no two children interacted simultaneously and that the overall duration matched that of the synchronous condition, each participant completed a total of 51 individual interactions.

Children are not explicitly instructed to synchronize but follow the system’s interaction prompts. As a result, perceived synchronization emerges spontaneously rather than being externally imposed. The joint activity lasts six minutes, providing equal exposure across conditions while maintaining consistent difficulty and objectives. Participants engage in direct interaction with the system and indirect interaction with peers, as their actions influence the collective Mandala construction. Refer to Supplementary Video – MR Experience for more details about the user-system interaction in each condition.

Experience closure. At the end of the experience, once the Mandala is fully constructed (Fig. 2C), the children observe how it expands and a fadeout to black provides a smooth ending to the experience. This phase lasts 7 s.

Study procedureEach session consisted of five stages, lasting approximately 42 min for each subgroup: (1) pre-questionnaire (demographics, music and dancing abilities, anxiety, and affiliation questions, 12 min); (2) The Moving Mandala experience (Demonstration - 5 min, Familiarization - 35 s, Joint activity - 6 min, and Closure - 7 s); (3) post-questionnaire (anxiety and affiliation questions, 6 min); (4) behavioral activities: resource allocation task (3 min) and social closeness activity (3 min); and (5) user experience questionnaire (6 min). The subgroups assigned to the "Baseline" followed another sequence of stages: 4, 1, 2, 3, and 5, which allowed us to observe the reactions of children on the behavioral tasks that had not gone previously through the MR system; however, due to ethical aspects, we allowed them to complete the remaining stages like the other children afterward. Fig. 4 shows the general procedure carried out with each subgroup (except the Baseline condition).

Data gathering and measuresData were collected through system-generated logs, non-technological behavioral tasks, and online questionnaires created using SoSci Survey Software (Leiner, 2021). The questionnaire items can be found in the Supplementary Material - Questionnaire.

Hypothesis 1. The impact of background music on IPS was analyzed through system-generated data and the UX questionnaire.

H1.1. User performance. The system generated a .log file tracking whether players activated the glitter cloud during each interaction. User performance was evaluated based on the activation frequency relative to the 25 possible interactions in the latter half of the experience, as the first half served for familiarization with the mechanics.

H1.2. Perceived music assistance. Children answered the question: "Did the music help you know when to touch the glitter?" using a two-sided slider ranging from "Never" (0) to "Always" (100), with numerical values hidden from participants.

Hypothesis 2. The impact of synchronous (experimental), asynchronous (control), and no prior movements (baseline) on prosocial behavior and social bonding was assessed using an affiliation questionnaire and two non-technological behavioral tasks: resource allocation and social closeness activities.

H2.1. Affiliation questionnaire (liking the others and feeling part of a team). Perceived affiliation was measured before and after playing The Moving Mandala experience through two items adapted from previous studies (Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016): (1) “How much do you feel you are part of a team with the other children in this room?” and (2) “How much do you like the other children in this room?”. Responses were recorded on a two-sided slider from "Not at all" (0) to "Very much" (100), with numerical values hidden from participants. Each item was treated as continuous data, and the difference between pre- and post-scores was calculated for each user and condition.

H2.2. Resource allocation task. We adapted the validated tests by Benenson et al. (2007); Rabinowitch and Meltzoff (2017a), originally designed for dyads, to accommodate four users. To ensure the task was well-suited for this adaptation, we conducted an iterative refinement process for the materials. This activity assessed children’s willingness to share resources, exploring the effects of synchronous versus non-synchronous movements on sharing behavior. Each child was positioned in front of a table, preventing them from seeing or hearing their peers’ responses. On each table, two fixed, lidded boxes were labeled “For my playmates” (left box) and “For me” (right box), with cardboard dividers ensuring privacy (Fig. 5). To eliminate potential biases, researchers positioned themselves away from the task area. Children were given nine identical gummy bears and instructed: "There are some gummy bears on the table. Now, if you wish, you can give some of your gummy bears to your playmates. You can choose to give none, some, or all. The decision is entirely up to you. There is no right or wrong answer, and no one will know what you choose". After completing the task, the children covered the boxes and raised their hands. Two researchers then recorded their choices, with the percentage of gummy bears shared with playmates serving as a measure of prosocial behavior in the analysis. To confirm preference, children were asked if they liked the gummy bears. This task was always conducted first to prevent bias from the subsequent social closeness activity, where responses were visible to peers.

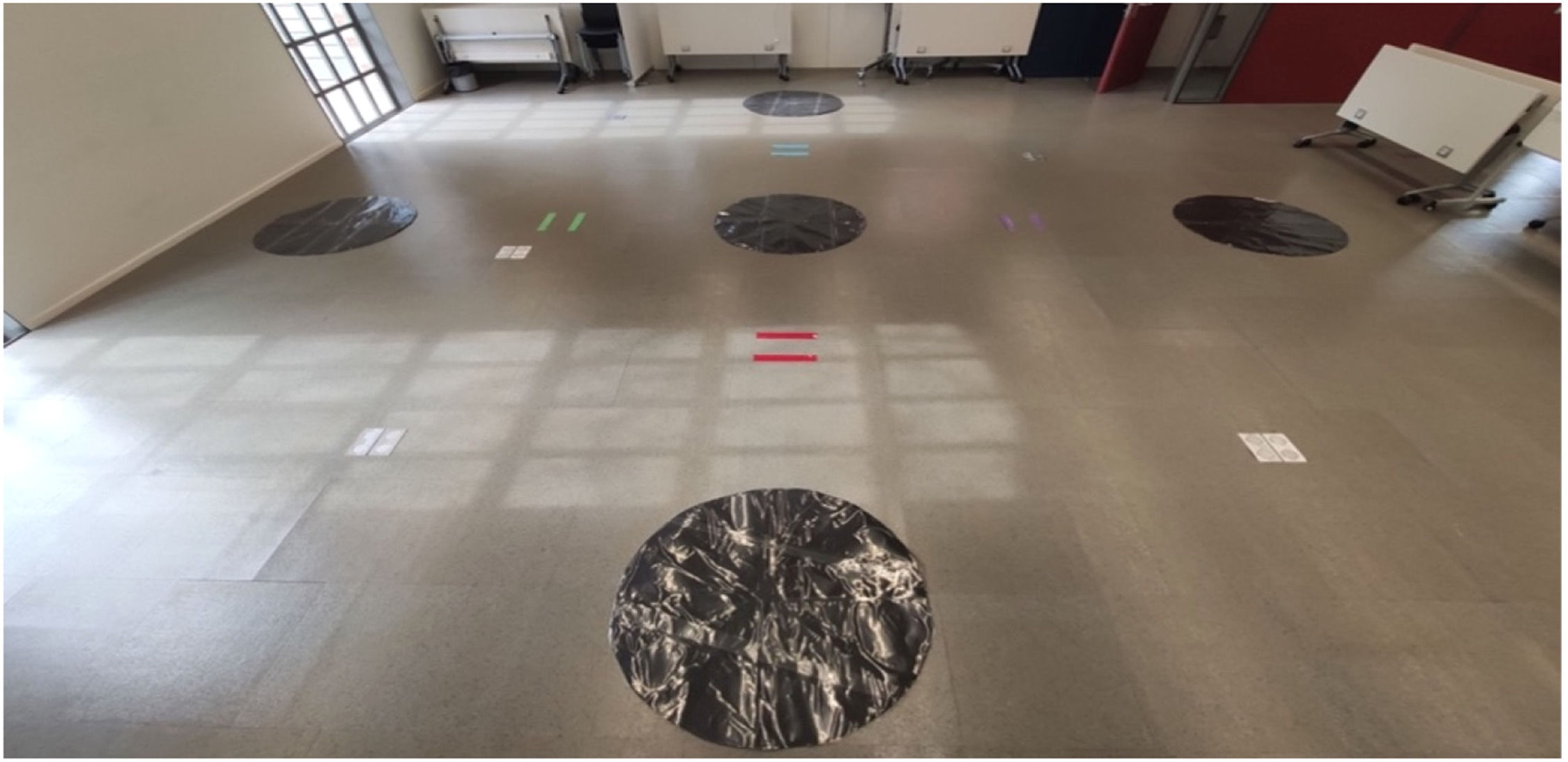

H2.3. Social closeness activity: The Lava Game. The second task assessing prosocial behavior measured physical proximity as an indicator of social closeness and bonding (Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016). We adapted The Island Game (Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016), a validated proxemics test originally designed for two groups of three participants, to accommodate a single group of four users. To ensure the adaptation was effective, we conducted an iterative refinement process for the task setup. This activity was conducted immediately after the Resource allocation task. Five black circular cardboard cut-outs (100 cm diameter) were placed on the floor as “buttons”, replicating the original setup. One button was positioned at the center, with the remaining four placed two meters away in north, east, south, and west positions (Fig. 6). Each child was assigned a starting position on a color-coded mark (matching the color of their interactive object in the Moving Mandala experience) located midway between the central island and one of the outer islands. To enhance motivation and reduce reaction time, we introduced a background story. Children were instructed: "You have two magic buttons on each side of you: one in the center and another farther out. Raise your arm if you see both magic buttons. The floor will turn to lava, but you can save yourself if, when I count to three and say ‘Now!’ you quickly touch one of your magic buttons with your hands. This way, the floor will not turn to lava. Are you ready? Raise your hand if you have understood the game". Once comprehension was confirmed, lava sound effects played, and they were reminded: "It seems the floor is turning to lava, quickly, place your legs and hands on the marks and look at the floor. 3, 2, 1, now, touch one of your buttons". At that moment, children chose between moving toward the inner circle (accessible to all group members) or the outer circle (individual access only). Two researchers recorded their choices.

Data analysisAll statistical analyses were conducted using the open-source software JASP (Jeffrey’s Amazing Statistics Program). The distribution of data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test (p > .05) to evaluate deviations from normality. Additionally, we examined potential differences based on sex and gender, including these analyses only when significant differences were found.

Impact of background music on IPS (H1.1 and H1.2). A Mann–Whitney U test (p < .05) was conducted to compare the two independent conditions: Experimental 1 and Experimental 2. We excluded three cases from Experimental 1 and five from Experimental 2 in the perceived music assistance item (H1.2) due to missing responses. Effect sizes were calculated using rank-biserial correlation. A post hoc power analysis was conducted with GPower (α = 0.05, d = 0.5, N = 124), indicating a power of 1–β = 0.87 to detect medium effect sizes.

Affiliation perception (H2.1 - liking the others and feeling part of a team). For the analysis, we calculated the difference in item scores before and after the MR experience and used a Kruskal–Wallis H test (p < .05) to assess whether there were significant differences between the Experimental 1, Experimental 2, and Control conditions. Based on the results, we conducted additional within-group analyses to compare pre- and post-scores. A paired-sample t-test (p < .05) was used for the Experimental 2 condition, while the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < .05) was applied to the Experimental 1 and Control conditions. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d for parametric data and rank-biserial correlation for non-parametric data. A post hoc power analysis was conducted with GPower (α = 0.05, d = 0.5, N = 59), indicating a power of 1–β = 0.98 to detect medium effect sizes. We excluded 12 and 11 cases from the liking the others and feeling part of a team items, respectively, due to missing responses on either the pre- or post-assessment.

Resource allocation task (H2.2). A Kruskal–Wallis H test (p < .05) was conducted to compare the four independent conditions: Experimental 1, Experimental 2, Control, and Baseline. Twelve cases were excluded in which children either did not like the gummy bears or changed their choices after observing others. A post hoc power analysis was conducted with GPower (α = 0.05, f = 0.25, N = 256), indicating a power of 1–β = 0.93 to detect medium effect sizes.

Social closeness activity (H2.3). We analyzed each child's choice, solo (outer) button or group (central) button, across the four conditions (Experimental 1, Experimental 2, Control, and Baseline) using a Chi-square test (p < .05). Thirty-five cases were excluded due to movement after observing others, directing peers, or because the subgroup initiated movement earlier but not simultaneously. Effect sizes were calculated based on Cramer’s V. A post hoc power analysis was conducted with GPower (α = 0.05, w = 0.3, N = 233, df = 3), indicating a power of 1–β = 0.98 to detect medium effect sizes.

ResultsThis section reports the results addressing each specific hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1 - Impact of background music on IPS.

H1.1. User performance. Shapiro-Wilk tests indicated significant deviations from normality for Experimental 1 (W = 0.95, p = .007) and Experimental 2 (W = 0.94, p = .006) conditions. There were statistically significant differences in user performance (glitter cloud activation frequency) between Experimental 1 (M = 0.625, SD = 0.252, Mdn = 0.68) and Experimental 2 (M = 0.48, SD = 0.28, Mdn = 0.46) conditions, U = 2795.5, p = .005, rrb = 0.29.

H1.2. Perceived music assistance. Shapiro-Wilk tests indicated significant deviations from normality for Experimental 1 and Experimental 2 conditions (p < .001). There were no statistically significant differences between Experimental 1 (M = 69.65, SD = 31.6, Mdn = 85) and Experimental 2 (M = 64.25, SD = 35.2, Mdn = 72) conditions, U = 2065.5, p = .46, rrb = 0.08.

Hypothesis 2. Impact on prosocial behavior and social bonding.

H2.1. Affiliation perception.

Liking the others. Shapiro-Wilk tests showed deviations from normality for Control (p < .001), Experimental 1 (p < .001), and Experimental 2 (p < .001) conditions. A Kruskal-Wallis H test revealed no statistically significant differences between Control (M = 0.39, SD = 19.9, Mdn = 0), Experimental 1 (M = 1.92, SD = 13.38, Mdn = 1), and Experimental 2 (M = 4.05, SD = 13.56, Mdn = 0) conditions, χ2(2) = 0.4, p = .82. All statistics for the within-group analyses to compare pre- and post-scores are shown in Table 3.

Pre- and post-affiliation perception (liking the others and feeling part of a team) statistics.

Feeling part of a team. Shapiro-Wilk tests indicated significant deviations from normality for Control (p = .009) and Experimental 1 (p < .001) conditions, but not for Experimental 2 condition (p = .24). A Kruskal-Wallis H test revealed no statistically significant differences between Control (M = 7.55, SD = 23.93, Mdn = 5), Experimental 1 (M = 3.45, SD = 21.3, Mdn = 1), and Experimental 2 (M = 6.93, SD = 19.62, Mdn = 2) conditions, χ2(2) = 1.21, p = .55. All the statistics for the within-group analyses to compare pre- and post-scores are shown in Table 3.

H2.2. Resource allocation task. Shapiro-Wilk tests showed deviations from normality for Baseline (p < .001), Control (p = .001), Experimental 1 (p = .004), and Experimental 2 (p = .01) conditions. There were no statistically significant differences in the percentage of gummy bears shared with playmates between Baseline (M = 50.2, 5 gummy bears; SD = 21.61; Mdn = 44.44), Control (M = 41.94, 4 gummy bears; SD = 21.76, Mdn = 44.44), Experimental 1 (M = 41.79, 4 gummy bears; SD = 23.06; Mdn = = 44.44), and Experimental 2 (M = 40.68, 4 gummy bears; SD = 24.8; Mdn = 44.44) conditions, χ2(3) = 5.45, p = .14.

H2.3. Social closeness activity: The Lava Game. There were no significant differences in children’s magic button choices between conditions, X2(3) = 4.98, p = .17. No significant associations were found between children’s sex and gender and magic button choices (sex: p = .06; gender: p = .09). Table 4 shows the frequencies of children’s choices by condition, sex, and gender.

Frequencies (n) and percentages of children's Lava Game responses by factors of condition, sex, and gender and chi-square test results.

Given the lack of significant differences in the perceived affiliation (liking the others and feeling part of a team) and behavioral tasks between the Experimental 1 (synchronous and rhythmic music), Experimental 2 (synchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music), and Control (asynchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music) conditions, we conducted an additional analysis to ensure that these findings were not due to confounding factors. We verified that all conditions had comparable user experience levels, including difficulty, task and movement comprehension, and satisfaction. However, even though the experience was designed to minimize inter-user activation time differences in the Experimental conditions, we found no significant differences in perceived synchrony between conditions. Refer to Supplementary Material – Additional Analysis for details on the analysis and results.

DiscussionThis study aimed to analyze how a full-body Mixed Reality experience, called The Moving Mandala, can facilitate interpersonal synchrony and foster prosocial behavior and social bonding among children. The experience was developed to foster intuitive and face-to-face real-time interactions in a playful shared virtual-real space. The following section discusses the results related to the two main objectives of the study: (1) to analyze the impact of auditory stimuli in facilitating interpersonal synchrony, and (2) to examine the effects of the interactive experience, performed with either synchronized or asynchronized movements, on prosocial behavior and social bonding.

Effects of auditory stimuli on IPSConsistent with our first subhypothesis (H1.1), children exposed to rhythmic music (Experimental 1) showed significantly better performance (higher glitter cloud activation rates) compared to those in the non-rhythmic ambient condition (Experimental 2). This effect emerged when the system guided all users through a repetitive and predictable movement sequence, requiring simultaneous action. This result is consistent with previous findings suggesting that rhythmic music can act as an external stimulus, serving as a "time giver" for entrainment (Bernieri & Rosenthal, 1991; Hardy & LaGasse, 2013). By overlapping with the visual cues provided by the system, the rhythmic pattern likely enabled children to better anticipate the timing of each interaction, thereby facilitating temporal alignment with both the system and their peers (Trost et al., 2017). This anticipatory process may have contributed to the stabilization of interpersonal synchrony (Bente & Novotny, 2020), highlighting the potential of rhythmic auditory stimuli to scaffold synchrony through enhanced motor prediction. This aligns with Stupacher et al. (2017), who found that music, compared to a metronome or silence, increased observers' sensitivity to interpersonal synchrony and social expectations about moving together.

Interestingly, and contrary to our second subhypothesis (H1.2), children did not perceive rhythmic music as more helpful than ambient sound for performing the activity, despite the observed performance differences. This suggests that rhythmic music may support active coordination at an implicit level. This finding opens new avenues for research focused on exploring the effects of different types of auditory stimuli, both rhythmic and non-rhythmic, as well as users’ reaction times from the moment the interactive visual appears, in relation to their perceived sense of support. Such investigations could lead to a more nuanced understanding of the underlying mechanisms through which rhythmic music, depending on its specific temporal and structural characteristics, facilitates interpersonal movement synchrony, both objectively and subjectively. For instance, in our study, the rhythmic music was designed to gradually increase the harmonic density by adding instruments over time. Although participants reported a high perception of support with the rhythmic soundtrack, it would be interesting to examine whether a simpler harmonic arrangement, where the beat associated with user interaction is more clearly perceived, might yield different results.

Building on insights from previous work such as OSMoSIS (Ragone et al., 2020) and FUTUREGYM (Takahashi et al., 2018), the results offer design insights that may inform the development of synchrony-based MR interventions. Specifically, the combination of predictable interaction sequences, shared visual cues, and rhythmic auditory input emerged as an effective configuration to support temporal coordination in immersive group settings. While no standardized guidelines currently exist for designing MR experiences that promote interpersonal synchrony with the aim of fostering prosocial behavior in children, this study contributes empirical evidence that serves as a foundation for more consistent and replicable design practices.

Impact of synchrony on prosocial behavior and social bondingContrary to our second hypothesis, the results did not show significant differences in affiliation perception (liking the others and feeling part of a team; H2.1), sharing resources with playmates (H2.2), and social closeness (H2.3) between the Experimental 1 (synchronous and rhythmic music), Experimental 2 (synchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music), Control (asynchronous and non-rhythmic ambient music), and Baseline (no prior movement) conditions. These findings contrast with previous research showing how interpersonal synchrony, fostered through non-technological means, increases helping, sharing, and affiliative behaviors (Kirschner & Tomasello, 2010; Rabinowitch & Meltzoff, 2017a; Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016). The supplementary analysis allowed us to discard the possibility that the lack of significant differences was due to potential confounding factors, such as the user experience. The results show that children found the activity easy to perform, understood both the task and the required movement, and reported high levels of satisfaction across all conditions. This suggests that the experience was well-calibrated in terms of engagement and accessibility. The game-based and interactive structure helped sustain motivation, unlike traditional synchrony tasks that often lack a playful objective (Qian et al., 2020; Rabinowitch & Meltzoff, 2017a; Tunçgenç & Cohen, 2016; Wan & Zhu, 2021). Regarding interpersonal synchrony, participants showed positive levels of peer awareness in all experiences. However, their subjective perception of moving in unison with others did not differ significantly between the synchrony conditions (Experimental) and the asynchrony condition (Control). This can be attributed to the implementation of synchrony in The Moving Mandala, which was intentionally designed to allow each child to interact independently with the system. As a result, individual performance was not contingent upon the actions of others. This inclusive approach, aimed at avoiding negative stigmatization for lower-performing players, meant that sometimes not all four users activated their glitter clouds simultaneously. This is supported by the activation frequency levels, which did not reach the ideal range of 90–100 %. This finding suggests that certain design aspects of the experience may have posed challenges for some users.

First, the interaction design required participants to recall and respond to the changing spatial location of the virtual stimulus (the glitter cloud), which appeared in a different position at each turn. This memory-dependent mechanic may have increased cognitive load. Future iterations could benefit from simplifying the interaction design to enhance intuitiveness and reduce reliance on short-term memory.

Second, the time window allowed for activating the glitter cloud was limited to one second. Although fast visual cues may be effective under certain conditions in promoting synchrony perception, this duration may have been insufficient in the absence of rhythmic auditory cues (as in Experimental 2 condition) and for possible individual differences in reaction time. Additionally, the inherent latency of vision-based tracking technologies may have compromised the responsiveness of the interaction between the user and the system.

Taken together, these factors may have contributed to the lower performance observed in some participants. As a result, the visual feedback associated with peer contributions, namely, the glitter rivers flowing to the center, was sometimes absent. This could reduce the salience of co-player actions and diminish children's awareness of the collective aspect of the task, weakening the conditions under which synchrony might foster prosocial effects. This highlights that rhythmic musical exposure alone may not be sufficient to foster prosocial outcomes; rather, these effects are more likely to emerge when music successfully supports shared motor alignment. As shown by Stupacher et al. (2017), prosocial evaluations were enhanced when the other individual moved in time with the beat, underscoring the role of rhythmic alignment in shaping social perception. At the same time, and unlike traditional synchrony paradigms (Cross et al., 2019) involving simple and repetitive tasks in dyadic face-to-face setups, this experience required children to divide their attention between spatial visual cues, sound, interactive objects, and their peers’ movements. This cognitive load may have diluted their focus on others' behavior, limiting recognition of synchrony as a shared and socially meaningful experience. Future designs should consider adjusting interaction timing to account for both system latency and user variability. These adjustments are especially relevant in contexts where rhythm-based temporal cues are absent and cannot support the timing of user responses.

In addition to the results concerning the impact of synchrony on prosocial behaviors and social bonding, we also observed interesting effects related to affiliation. Specifically, an increase in participants’ perception of liking their peers and feeling part of a team was reported only after playing the synchronous version of The Moving Mandala with non-rhythmic ambient music (Experimental 2 condition). Moreover, a similar increase in the perception of feeling part of a team was also found after playing the asynchronous version with non-rhythmic ambient music (Control condition). These results suggest that The Moving Mandala, when performed with ambient non-rhythmic music, has a positive impact on children's sense of group affiliation. This finding supports the potential of full-body interactive games within Mixed Reality systems to promote social connectedness among children. Notably, the same effect was not observed in the synchronous condition with rhythmic music (Experimental 1). One possible explanation could lie in the focus of attention elicited by the different auditory stimuli. While rhythmic music facilitates temporal alignment, it could also draw the user’s attention more toward their performance, rather than toward the group as a whole. In contrast, ambient non-rhythmic music likely places fewer demands on precise timing, allowing participants to remain more attuned to the presence and movements of others. From a Mixed Reality design perspective, this highlights the importance of considering not only the functional role of audio cues in facilitating coordination, but also their social and emotional implications. While some rhythmic structures can support synchronization, they may not always foster a sense of interpersonal connection or group cohesion.

Together, these findings highlight the importance of designing MR environments that integrate simplicity, perceptual visibility of peer actions, and manageable cognitive demands to support positive social interactions through synchrony.

Limitations and future directionsAlthough the experience was designed following inclusive principles, the study involved only a subset of the child population. To better assess its broader applicability and inclusive potential, future research should involve children with neurocognitive diversity. Understanding how they engage with the system will provide valuable insights to refine the design and ensure its accessibility, adaptability, and effectiveness across a wider spectrum of users. Moreover, future studies should explore potential gender effects by comparing same-gender groups (all boys and all girls) with mixed-gender groups, as well as examine how familiarity among group members influences outcomes. These factors may play a relevant role in how children experience synchrony and develop prosocial responses in collaborative settings. In addition, while the study was adequately powered to detect medium effects, some analyses yielded small effect sizes, highlighting the need for larger samples in future research to ensure sufficient power to detect more subtle effects.

ConclusionThe Moving Mandala illustrates the potential of face-to-face full-body Mixed Reality experiences as engaging and developmentally appropriate tools for exploring interpersonal synchrony among children. These systems are well received by them and present a promising alternative to traditional non-technological activities, offering dynamic, embodied, and naturalistic contexts for studying the impact of interpersonal synchrony in prosocial behaviors. While no significant differences were found across conditions in prosocial behaviors such as affiliation, sharing, or proxemics, the study provides evidence that rhythmic auditory cues can enhance synchronous movement in multi-user settings. This suggests that MR experiences incorporating rhythmic structures may be particularly effective in supporting temporal alignment between participants. However, they also highlight key design considerations. Experiences based on simple and intuitive tasks, rather than cognitively demanding ones, may be more effective in enhancing group awareness and fostering a shared sense of connection. Therefore, further research is needed to find the right balance between supporting interpersonal synchrony and promoting prosocial behavior, within the wide range of design possibilities these systems offer.

By bridging insights from Child-Computer Interaction, developmental psychology, and embodied interaction design, this study contributes to the development of more inclusive MR environments. The findings inform future therapeutic and educational interventions that aim not only to facilitate coordination, but also to nurture the social-emotional development of children through movement-based play.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the author(s) used ChatGPT to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FundingThis work has been funded by UPF’s funding program (PW2021-PR05).

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We thank Edgar Gil for developing the MR interactive game and the children who participated in the study.