Chronic hepatitis E virus (HEV) in persons with immune impairment has a progressive course leading to a rapid progression to liver cirrhosis. However, prospective data on chronic HEV is scarce. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and risk factors for chronic HEV infection in subjects with immune dysfunction and elevated liver enzymes.

Patients and methodsCHES is a multicenter prospective study that included adults with elevated transaminases values for at least 6 months and any of these conditions: transplant recipients, HIV infection, haemodialysis, liver cirrhosis, and immunosuppressant therapy. Anti-HEV IgG/IgM (Wantai ELISA) and HEV-RNA by an automated highly sensitive assay (Roche diagnostics) were performed in all subjects. In addition, all participants answered an epidemiological survey.

ResultsThree hundred and eighty-one patients were included: 131 transplant recipients, 115 cirrhosis, 51 HIV-infected subjects, 87 on immunosuppressants, 4 hemodialysis. Overall, 210 subjects were on immunosuppressants. Anti-HEV IgG was found in 94 (25.6%) subjects with similar rates regardless of the cause for immune impairment. HEV-RNA was positive in 6 (1.6%), all of them transplant recipients, yielding a rate of chronic HEV of 5.8% among solid-organ recipients. In the transplant population, only therapy with mTOR inhibitors was independently associated with risk of chronic HEV, whereas also ALT values impacted in the general model.

ConclusionsDespite previous abnormal transaminases values, chronic HEV was only observed among solid-organ recipients. In this population, the rate of chronic HEV was 5.8% and only therapy with mTOR inhibitors was independently associated with chronic hepatitis E.

La infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis E (VHE) en personas con disfunción inmunitaria tiene un curso progresivo conllevando una rápida progresión a cirrosis hepática. Sin embargo, los datos prospectivos a este respecto son escasos. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la prevalencia y factores de riesgo para la infección crónica VHE en sujetos con disfunción inmunitaria y elevación de enzimas hepáticos.

Pacientes y métodosCHES es un estudio prospectivo multicéntrico que incluyó adultos con transaminasas elevadas durante al menos 6 meses y alguno de estos factores: receptores de trasplante, infección por VIH, hemodiálisis, cirrosis hepática o tratamiento inmunosupresor. En todos los sujetos se realizaron IgG/IgM anti-VHE (Wantai Elisa) y ARN-VHE por una técnica super sensible (Roche Diagnostics). Además, todos los participantes contestaron una encuesta epidemiológica.

Resultados381 pacientes fueron incluidos: 131 trasplantados, 115 cirróticos, 51 infectados por VIH, 87 bajo inmunosupresores, 4 hemodiálisis. En total, 210 sujetos recibían inmunosupresores. La IgG anti-VHE fue positiva en 94 (25,6%) sujetos, con tasas similares en todas la causas de disfunción inmunitaria. El ARN-VHE fue positivo en 6 (1,6%) pacientes, todos ellos trasplantados, siendo la tasa de infección crónica VHE en receptores de órgano sólido del 5,8%. En la población de trasplantados, solo el tratamiento con inhibidores de mTOR se asoció de forma independiente a la hepatitis crónica VHE, mientras que los niveles de ALT impactaron en el modelo general.

ConclusionesA pesar de los niveles anormales de transaminasas, solo se objetivó hepatitis crónica VHE en trasplantados de órgano sólido. En esta población, la tasa de hepatitis crónica VHE fue del 5,8% y solo el tratamiento con inhibidores de mTOR se asoció de forma independiente a la hepatitis crónica E.

Chronic hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection is nowadays an accepted cause of chronic liver disease in immunocompromised individuals.1 Although that first series from Kamal et al. focused on solid-organ transplant recipients in 2008,2 there is increasing evidence of the risk of chronic hepatitis E in patients with other sources of immune impairment such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,3 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection4,5 or even underlying liver disease,6,7 the latter especially in the context of unexplained alanine aminotransferase (ALT) flares.1

The importance of chronic hepatitis E lies in the rapid development of liver fibrosis and progression to cirrhosis due to the immune dysfunction of these patients.8 Screening of chronic hepatitis E in immunocompromised patients with normal transaminases levels has shown an extremely low performance,9 and for this reason it is not systematically recommended.1

Overall, the prevalence of antibodies against hepatitis E in the blood banks throughout Europe range from 5% to 25%.10 The HEV seroprevalence may be influenced by many factors such as geographical region, the assay employed and the individual's age. However, to date, prevalence of chronic hepatitis E defined by persistent HEV viraemia for more than 3–6 months remains unknown. Preliminary data from a cross-sectional cohort in the United Kingdom in transplant patients receiving tacrolimus has shown an overall HEV-RNA prevalence of 0.67%, ranging from 0.6% in solid-organ to 2.1% among stem cell transplant recipients, though all individuals on tacrolimus were tested, regardless of the ALT levels.11

Concerning risk factors for chronic hepatitis E, it is well-known that the deeper the immunosuppression, the higher the risk of chronicity.2,12 Nevertheless, data on predisposing factors associated with increased risk of chronic infection are scarce and usually based on retrospective cohorts of solid-organ transplant patients.13 Most commonly reported factors linked to augmented rate of chronic hepatitis E are the use of tacrolimus and time from the transplant.2,13 Recently, Cornberg et al. reported the experience of Sofosbuvir monotherapy for the treatment of chronic hepatitis E in a small number of cases.14 Although no patient achieved undetectable HEV-RNA at the end of therapy, it seems that those on mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors presented a weaker antiviral response, as previously shown in in vitro studies.15,16

Our multicenter prospective study, entitled CHES (Chronic Hepatitis EScreening in patients with immune impairment) aimed to assess the prevalence of chronic hepatitis E among subjects with immune dysfunction and persistently elevated transaminases, and to identify risk factors for chronic HEV infection.

Patients and methodsStudy designCHES is a prospective, multicenter cohort study whose primary aim is to assess the prevalence and risk factors for chronic hepatitis E in adults with immune impairment and abnormal liver enzymes. Causes for immune dysfunction encompassed solid-organ and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), liver cirrhosis, HIV infection, end-stage chronic kidney disease on renal replacement therapy and subjects on immunosuppressive therapy for any condition, including biological therapies.

The secondary aim was to evaluate the seroprevalence of previous HEV infection assessed by anti-HEV IgG in a cohort of patients with immune impairment.

From January 2016 to December 2019, patients were recruited at the four participant hospitals. The inclusion criteria were subjects over 16 years diagnosed with any of the previously stated conditions associated with immune impairment plus the presence of ALT and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) above upper limit of normal in at least 2 determinations over the previous 6 months. The latter was based on the fact that the vast majority of patients with chronic hepatitis E present with increased transaminases values.11,13 Upper normal transaminases value was defined according to local reference laboratory levels (35IU/ml for women, 50IU/ml for men). Exclusion criteria were a short life expectancy (<6 months) and therefore low probability to attend the blood test appointment and/or absence of a signed consent.

MethodsCollected data included demographic and epidemiological information (sex, age, race, tobacco use and alcohol intake). Condition for immune impairment and time (years) from diagnosis were collected according to medical records: (1) solid-organ or stem cell transplantation, (2) liver cirrhosis, (3) HIV infection, (4) end-stage chronic kidney disease on renal replacement therapy, (5) immunosuppressant therapy for other disorders different from those previously listed. In the case of organ recipients, date of performance and transplanted organ were also included. Previous hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and past history of therapy with Ribavirin were recorded, as well as ALT and AST 6 months prior to the inclusion. In patients under immunosuppressant therapy, the drugs were classified as follows: corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors, purine inhibitors, mTOR inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies (anti-TNFα, anti-interleukins, anti-CD20, anti-IgG1) and others. Data on the type and dosage of the specific drug were also recorded.

At the time of inclusion, complete blood cell count including lymphocyte count with CD4, CD19 and natural killer that were analyzed in a NAVIOS EX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter), coagulation test and biochemical panel (liver enzymes, creatinine, bilirubin and albumin) were performed. Virological tests included Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), Hepatitis B core (anti-HBc), anti-HCV, anti-HEV IgG and IgM and HEV RNA.

HBsAg, anti-HBc, anti-HIV and anti-HCV were tested by commercially available immunoassays. HEV determinations including anti-HEV IgM and IgG and HEV RNA were performed in all cases. IgM and IgG anti-HEV were tested using Wantai ELISA tests (Wantai Biopharmaceutical, Beijing, China). HEV RNA was measured by real-time PCR Cobas HEV (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Basel Switzerland), which has a lower limit of detection of 18.6IU/ml. In cases with detectable HEV RNA, viral load was quantified using the HEV WHO International Standard (code number 6329/10; unitage of 250,000IU/ml).17 All HEV markers were performed in a central laboratory (Clinical Laboratories of Vall d’Hebron Barcelona Hospital Campus).

All cases with detectable HEV RNA were followed up and HEV RNA was repeated 3 months later in order to establish the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis E (defined by persistence of viraemia for more than 3 months).1 Patients treated with Ribavirin were follow up during antiviral therapy, and after discontinuation for a 48-week period to rule out relapse of the infection.

In order to assess factors associated with risk of chronic hepatitis E an epidemiological survey was completed by all subjects, including: eating habits (raw meat, game meat, homemade sausages, horse or wild boar meat, deer sausages or meat, foie, mussels, oysters), profession, living with animals, household location (rural area, defined as population <10,000 inhabitants, farm), occupation (hunting, slaughter); trips to HEV endemic areas (China, India, Mexico, Egypt) within the last 10 years.

This study was approved by the Vall d’Hebron Hospital ethics committee and the Spanish and European Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (PR(AG)29/2015 and protocol code REG-HEPE-2014-01, date of approval: 03/03/2017) and was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study, and all data were anonymized.

Statistical analysisNormally distributed quantitative variables were compared by the Student t test and expressed as the mean±standard deviation (SD). Variables with a non-normal distribution were analyzed by the Mann–Whitney U test and expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared or Fisher's exact test, when frequencies were less than 5%, and expressed as frequencies and percentages. Variables yielding p<0.05 in the univariate model were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for independent factors associated with chronic hepatitis E. Only patients with complete data for all variables were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was set at a p-value of <0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

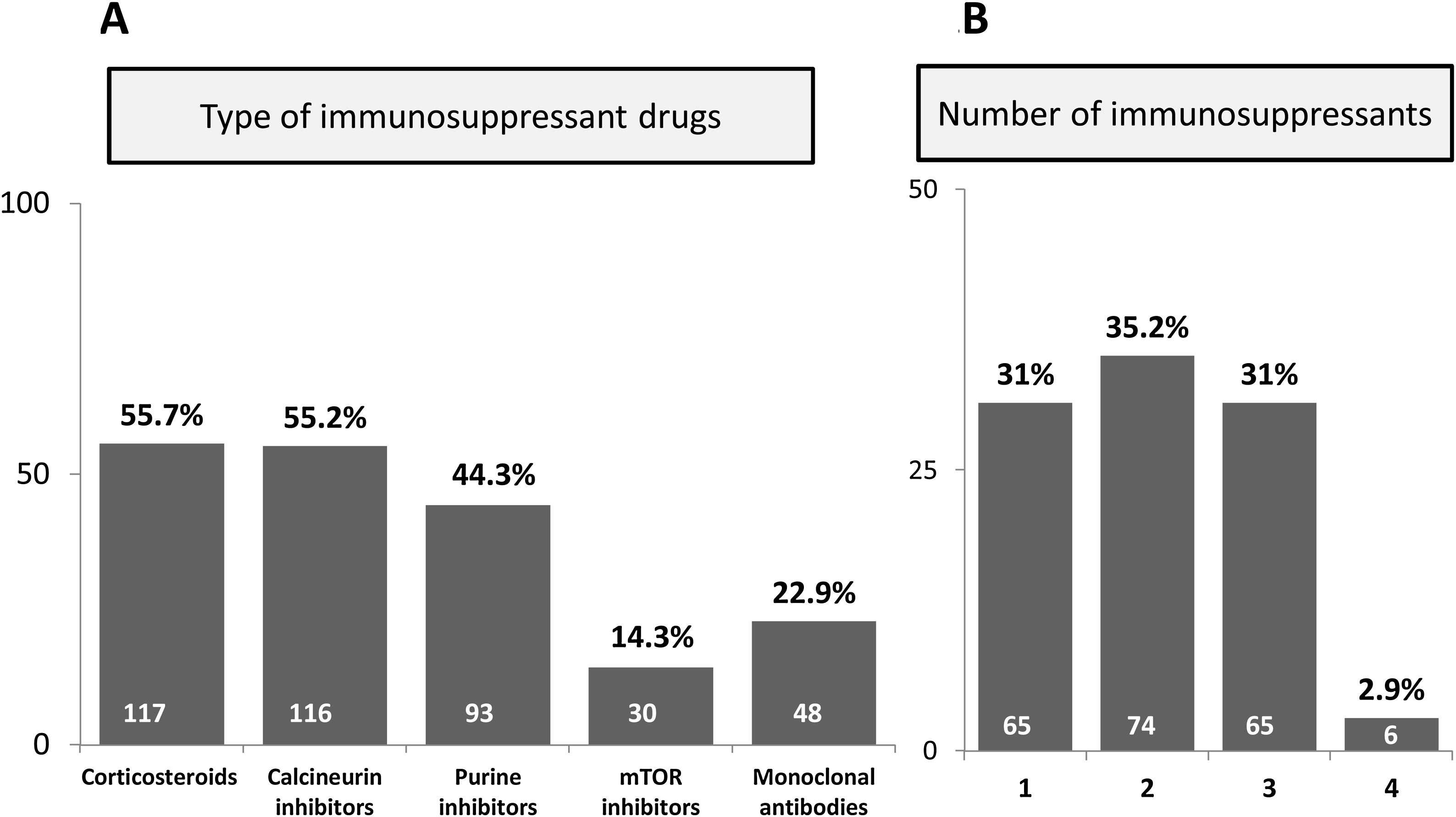

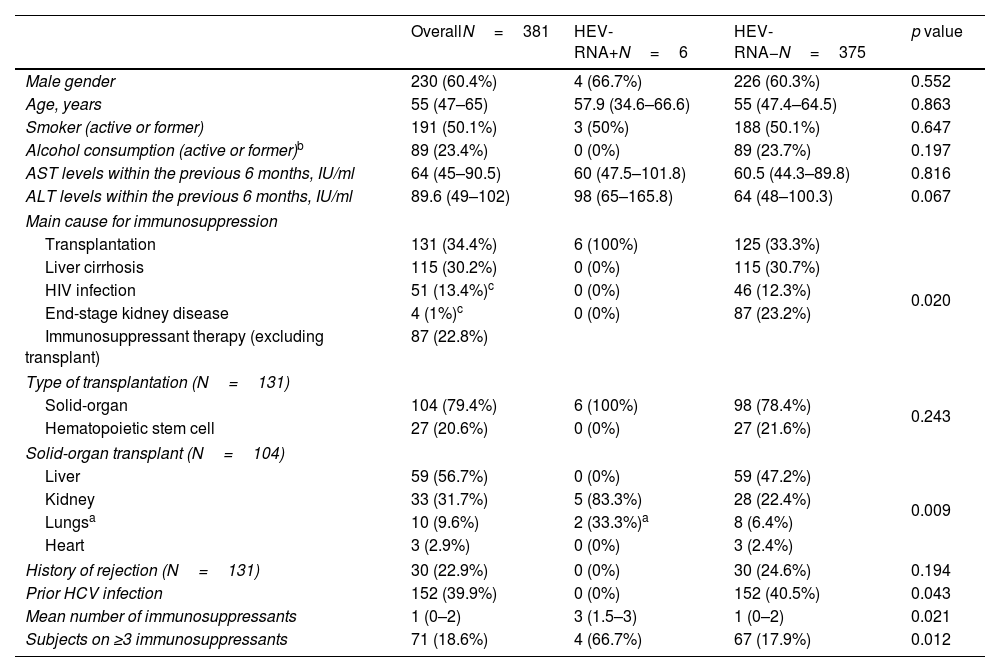

ResultsBaseline characteristics of patientsIn total, 381 subjects were included in the study. Main characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, sixty percent were male, median age 55 years, with a great majority of Caucasian subjects (341, 90.0%). The most prevalent cause for immune impairment was history of transplant (131 cases, 34.4%), followed by liver cirrhosis (115 subjects, 30.2%). Some patients presented more than one cause for immune dysfunction, for instance 5 HIV-infected subjects were also transplant recipients and from the 4 individuals on haemodialysis, one also suffered from HIV infection and another was a transplant receptor. Among the 131 graft recipients, 79.4% were solid-organ and 20.6% were HSCT. The most common solid-organ grafts were liver (56.7%) and kidney (31.7%). Median ALT values within the prior 6 months to inclusion were 89.6IU/ml, while median AST was recorded in 64IU/ml. On the whole, 210 individuals were receiving at least one immunosuppressive drug, with a median of two drugs per patient. The type and total number of immunosuppressive therapies are shown in Fig. 1.

Baseline characteristics of the overall cohort and according to the presence of detectable HEV-RNA.

| OverallN=381 | HEV-RNA+N=6 | HEV-RNA−N=375 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 230 (60.4%) | 4 (66.7%) | 226 (60.3%) | 0.552 |

| Age, years | 55 (47–65) | 57.9 (34.6–66.6) | 55 (47.4–64.5) | 0.863 |

| Smoker (active or former) | 191 (50.1%) | 3 (50%) | 188 (50.1%) | 0.647 |

| Alcohol consumption (active or former)b | 89 (23.4%) | 0 (0%) | 89 (23.7%) | 0.197 |

| AST levels within the previous 6 months, IU/ml | 64 (45–90.5) | 60 (47.5–101.8) | 60.5 (44.3–89.8) | 0.816 |

| ALT levels within the previous 6 months, IU/ml | 89.6 (49–102) | 98 (65–165.8) | 64 (48–100.3) | 0.067 |

| Main cause for immunosuppression | ||||

| Transplantation | 131 (34.4%) | 6 (100%) | 125 (33.3%) | 0.020 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 115 (30.2%) | 0 (0%) | 115 (30.7%) | |

| HIV infection | 51 (13.4%)c | 0 (0%) | 46 (12.3%) | |

| End-stage kidney disease | 4 (1%)c | 0 (0%) | 87 (23.2%) | |

| Immunosuppressant therapy (excluding transplant) | 87 (22.8%) | |||

| Type of transplantation (N=131) | ||||

| Solid-organ | 104 (79.4%) | 6 (100%) | 98 (78.4%) | 0.243 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell | 27 (20.6%) | 0 (0%) | 27 (21.6%) | |

| Solid-organ transplant (N=104) | ||||

| Liver | 59 (56.7%) | 0 (0%) | 59 (47.2%) | 0.009 |

| Kidney | 33 (31.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 28 (22.4%) | |

| Lungsa | 10 (9.6%) | 2 (33.3%)a | 8 (6.4%) | |

| Heart | 3 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2.4%) | |

| History of rejection (N=131) | 30 (22.9%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (24.6%) | 0.194 |

| Prior HCV infection | 152 (39.9%) | 0 (0%) | 152 (40.5%) | 0.043 |

| Mean number of immunosuppressants | 1 (0–2) | 3 (1.5–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0.021 |

| Subjects on ≥3 immunosuppressants | 71 (18.6%) | 4 (66.7%) | 67 (17.9%) | 0.012 |

All variables are expressed as n (%) or median (IQR).

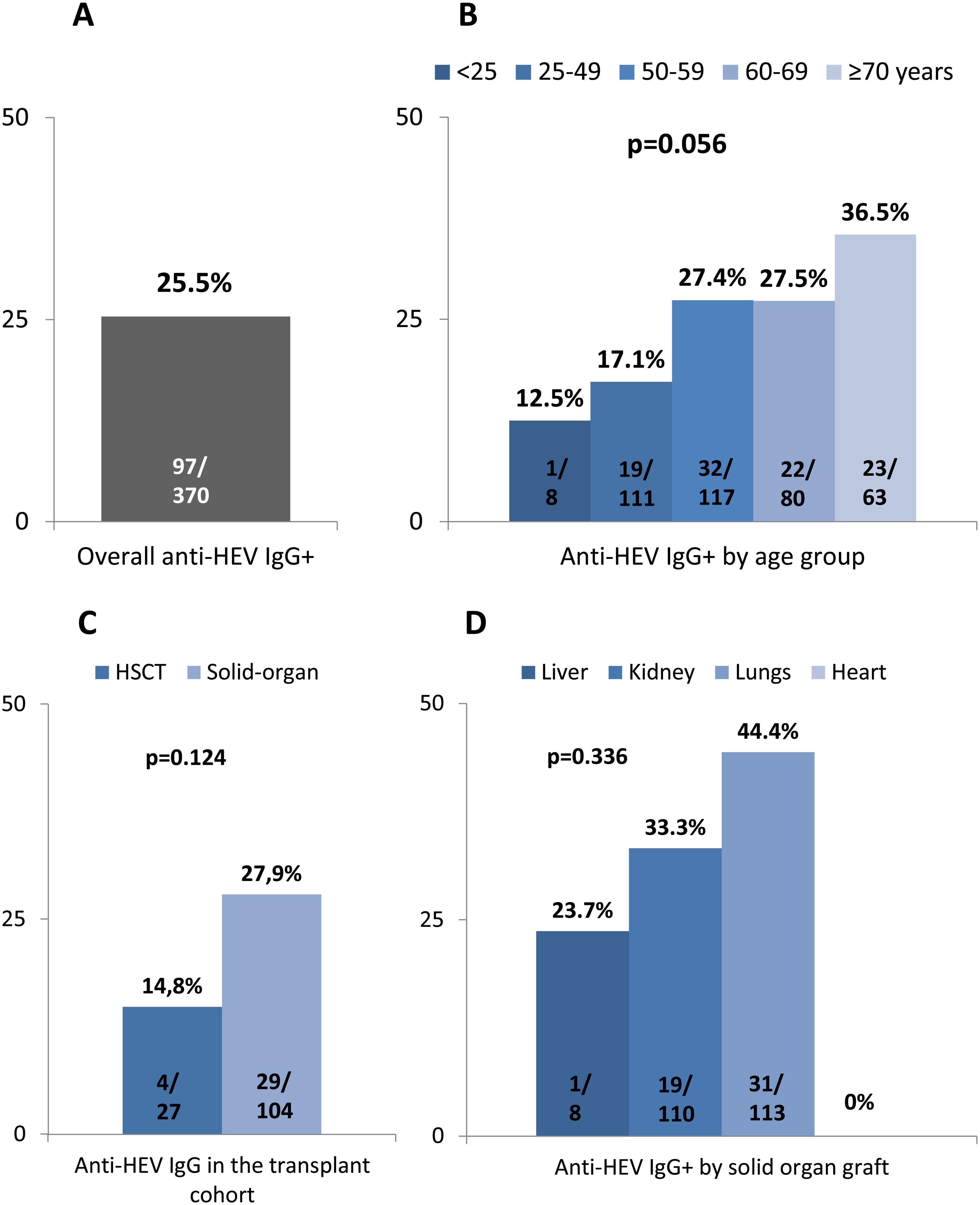

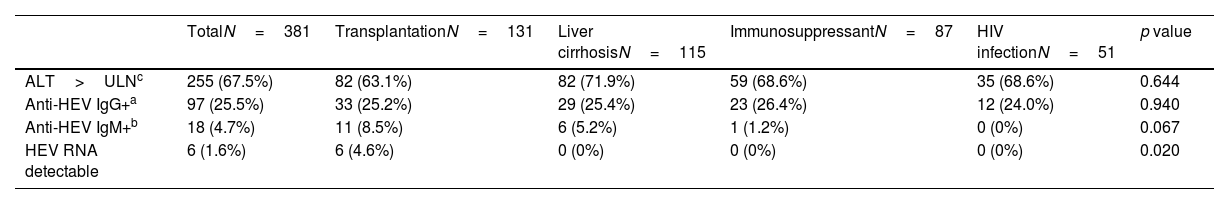

Altogether 97 out of 381 subjects (25.5%) tested positive for anti-HEV IgG, regardless of the cause for immune impairment (Table 2). Anti-HEV IgG could not be performed in 2 individuals and IgM in 3. There was a trend to higher anti-HEV IgG positivity in older subjects (p=0.056) as shown in Fig. 2. In patients receiving immunosuppressant drugs, seroprevalence did not differ according to either the drug type or number of immunosuppressant treatments (p=0.640). Solid-organ recipients tended to present a higher HEV seroprevalence than HSCT patients (p=0.124) as shown in Fig. 2 (panels C and D). No differences were observed among the solid graft population (p=0.336).

Anti-HEV IgG, IgM and HEV RNA according to the main cause for immunosuppression.

| TotalN=381 | TransplantationN=131 | Liver cirrhosisN=115 | ImmunosuppressantN=87 | HIV infectionN=51 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT>ULNc | 255 (67.5%) | 82 (63.1%) | 82 (71.9%) | 59 (68.6%) | 35 (68.6%) | 0.644 |

| Anti-HEV IgG+a | 97 (25.5%) | 33 (25.2%) | 29 (25.4%) | 23 (26.4%) | 12 (24.0%) | 0.940 |

| Anti-HEV IgM+b | 18 (4.7%) | 11 (8.5%) | 6 (5.2%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0.067 |

| HEV RNA detectable | 6 (1.6%) | 6 (4.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.020 |

ULN (upper limit of normality) was defined as 35IU/ml for women, 50IU/ml for men.

Table S1 summarizes the main epidemiological risk factors for the presence of anti-HEV IgG. Briefly, subjects who refer intake of game meat presented a higher HEV seroprevalence (p=0.024), as well as those who eat pork meat at least once a month (p=0.046). Regarding hobbies, individuals who practice hunting or have assisted in pig slaughter have greater risk of HEV exposition (p=0.041 and p=0.021, respectively).

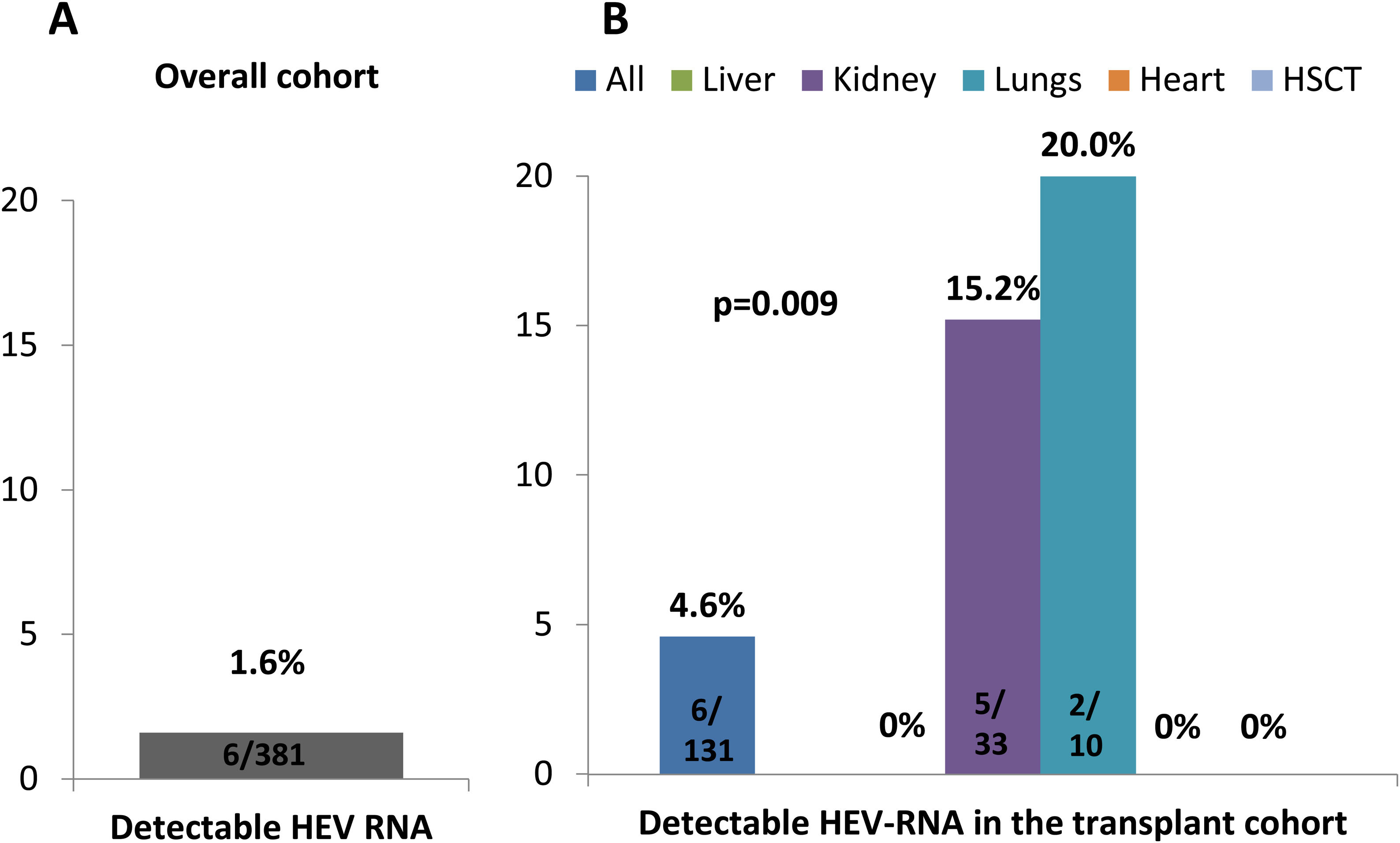

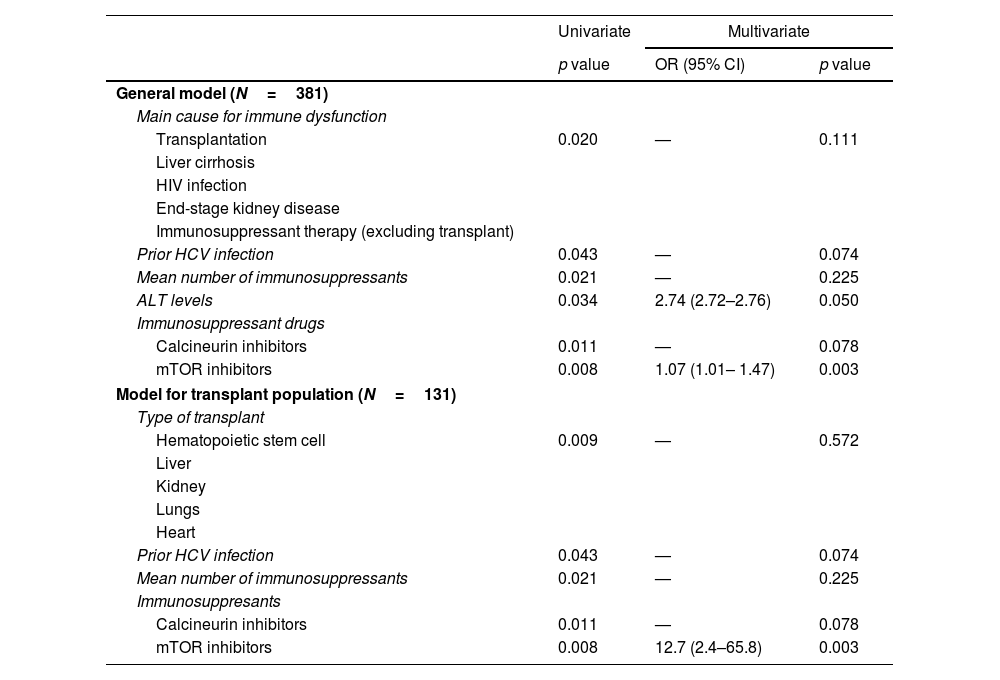

Characteristics and follow-up of patients with detectable HEV-RNAHEV-RNA was detected in 6 subjects, all of them solid-organ recipients, leading to an overall prevalence of 1.6% (Fig. 3). HEV-RNA remained detectable for more than three months in all six patients allowing the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis E. All were solid-organ transplant recipients (1 lung, 4 kidney, 1 lung plus kidney), yielding a prevalence of 4.6% (6/131) among the transplanted population and of 5.8% among the solid-organ graft recipients (Fig. 3). Since all HEV-RNA cases belonged to the transplant group, the proportion of HEV-RNA detectable cases differed according to the cause of immune impairment (p=0.020), despite the fact the proportion of positive anti-HEV IgG was similar (p=0.940), as shown in Table 2. Besides the cause for immune dysfunction, ALT levels within the previous 6 months to screening also tended to be higher among patients with later detectable HEV-RNA (p=0.067). Both the number of immunosuppressant drugs and the type impacted on the prevalence of HEV-RNA, with calcineurin and mTOR inhibitors therapy and three or more immunosuppressant drugs associated with a higher proportion of detectable HEV-RNA (p=0.012 and p=0.011, respectively) as summarized in Table 1. However, in the multivariate analysis, only treatment with mTOR inhibitors was independently linked to a greater risk of detectable HEV-RNA, with an OR of 12.7 (p=0.003) in the model restricted to the transplant population. In the pooled model, high ALT levels were independently associated with increased risk of HEV-RNA detection with an OR of 2.74 (p=0.050), as well as therapy with mTOR inhibitors with an OR of 1.07 (p=0.003). The multivariate analyses are shown in Table 3. Moreover, univariate and multivariate analysis restricted to the solid-organ transplant cohort are shown in supplementary Table S2.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with detectable HEV-RNA.

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| General model (N=381) | |||

| Main cause for immune dysfunction | |||

| Transplantation | 0.020 | — | 0.111 |

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| HIV infection | |||

| End-stage kidney disease | |||

| Immunosuppressant therapy (excluding transplant) | |||

| Prior HCV infection | 0.043 | — | 0.074 |

| Mean number of immunosuppressants | 0.021 | — | 0.225 |

| ALT levels | 0.034 | 2.74 (2.72–2.76) | 0.050 |

| Immunosuppressant drugs | |||

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 0.011 | — | 0.078 |

| mTOR inhibitors | 0.008 | 1.07 (1.01– 1.47) | 0.003 |

| Model for transplant population (N=131) | |||

| Type of transplant | |||

| Hematopoietic stem cell | 0.009 | — | 0.572 |

| Liver | |||

| Kidney | |||

| Lungs | |||

| Heart | |||

| Prior HCV infection | 0.043 | — | 0.074 |

| Mean number of immunosuppressants | 0.021 | — | 0.225 |

| Immunosuppresants | |||

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 0.011 | — | 0.078 |

| mTOR inhibitors | 0.008 | 12.7 (2.4–65.8) | 0.003 |

Differences in analytical factors between subjects with and without detectable HEV RNA are shown in supplementary figure. Briefly, ALT levels were higher among those with detectable HEV-RNA (97IU/ml vs. 57, p=0.034), though GGT values and platelets account were similar. Regarding immune response, the percentage of CD19+ T-cells tendered to be lower in those with detectable HEV viraemia (p=0.130), though the CD4+ and NK cells account were similar (p=0.815 and p=0.371, respectively). All patients with detectable HEV-RNA also were positive for both anti-HEV IgM and IgG. Overall, 18 subjects had anti-HEV IgM, six of them with simultaneous detectable HEV RNA and 13 with simultaneous anti-HEV IgG. In 5 patients anti-HEV IgM was the only HEV marker.

Median value of quantitative HEV-RNA was 3,870,000UI/ml (range, 40,000–11,000,000). Comparison with the 3-month HEV-RNA control after diagnosis showed similar viral load (p=0.285). Decrease of the immunosuppression (dosage and/or frequency) was only possible in two individuals but it did not turn out in a virologic response, therefore all 6 patients received Ribavirin. Liver elastography prior to antiviral therapy was carried out in 5 patients revealing liver stiffness measurement (LSM) below 6.5kPa in 4 cases 9.1kPa in another, value suggestive of moderate liver fibrosis. Patients received either a 12 or 24-week course of Ribavirin at dose of 600mg and 3 (50%) achieved a virological response 48 weeks after treatment discontinuation.

DiscussionIn this prospective study including patients with immune impairment and persistently increased transaminases levels, the overall prevalence of HEV-RNA was 1.6%, with all cases being solid-organ transplant recipients. The HEV-RNA prevalence, therefore, in the overall transplant population was 4.6% and even higher (5.8%) among solid-organ recipients. All cases were recipients of a lung, kidney or lung-kidney graft. HEV-RNA remained detectable for more than 3 months in all these cases, leading to the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis E. Therapy with mTOR inhibitors was the only independent risk factor associated with the detection of HEV-RNA with an OR of roughly 13 fold-risk of chronic HEV infection among the transplant population, whereas both mTOR inhibitors and ALT levels were independently associated in the pooled model.

Though the transplant setting is the most common factor associated with risk of chronic hepatitis E, almost all sources of immune dysfunction have been linked with HEV infection. For instance there is increasing data and awareness about HEV infection in patients undergoing immunosuppressive drugs for rheumatology disorders18,19 or inflammatory bowel disease.20 Patients on haemodialysis are known to have an increased HEV seroprevalence,21 with blood transfusion and duration of haemodialysis as potential risk factors for acquiring HEV infection.22 In addition, there is increasing evidence on the high prevalence of HEV seroprevalence in people with chronic liver disease, even in low-endemic areas for HEV such as the United States.23,24 HEV infection is a well-known, though probably underestimated, cause for acute decompensation among patients with alcohol-related chronic liver disease,25,26 leading to high mortality in case of development of acute-on-chronic liver disease.27 However, chronic HEV infection may also develop.6 This could be especially relevant in patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis. For example, in a study that contrasted the rate of anti-HEV IgG and HEV-RNA in healthy volunteers and 35 patients with cryptogenic liver cirrhosis, up to 8.5% of the latter presented detectable HEV-RNA, all of them with mildly increased ALT levels.28 Although this data emphasises the need for ruling out HEV infection in subjects with liver cirrhosis and elevated transaminases, in our cohort no case with underlying liver cirrhosis tested positive, despite the fact the anti-HEV IgG rate was very similar to the transplant group (25.4% vs. 24.4%, p=0.940). Regarding HIV infection, in a recent meta-analysis including 120 studies, detection of HEV-RNA was statistically higher in the transplant population than in HIV-infected subjects (1.2% vs. 0.39%, p=0.0011),29 data in line with our study, where all HEV-RNA positive cases were transplant recipients.

In the pooled model including all patients, ALT values showed an OR of 2.74, highlighting the importance of screening among patients with increased transaminases levels. This data supports the rationale of our study, since based on previous reports and the low likelihood of chronic hepatitis E in patients with normal ALT levels,11,13 only subjects with prior AST and/or ALT elevated were recruited.

Regarding risk factors for HEV infection, tacrolimus, a calcineurin inhibitor, has been pointed out as the main predictor for chronic HEV infection in the transplantation setting,13 though this fact comes from retrospective cohorts. However, results from in vitro studies have suggested that HEV replication is not just facilitated by the immunosuppressive status but can also be enhanced by the type of immunosuppressant drug. In that sense, Wang et al. described that calcineurin inhibitors promoted in vitro replication of HEV and mycophenolate inhibited viral replication by nucleotide depletion.16 Likewise, Zhou et al. showed that mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin or everolimus facilitated HEV replication. They demonstrated that HEV-RNA silenced an mTOR pathway (PI3K-PKB-mTOR) resulting in a significant increase in intracellular concentrations of HEV-RNA.15 In addition, a recent study suggests that mTOR inhibitors can directly promote replication of other viruses such as poliomaviruses, which include BK virus, a relatively common infection among solid-organ transplant patients.30 Our study provides data on the risk of HEV infection linked with mTOR inhibitors, since this was the only independent factor associated with the infection in our prospective cohort. This contrast with few reports where a lower total lymphocyte, CD3-positive and CD-4 cells count were associated with higher risk of chronic hepatitis E.2 We did not find differences on the CD4-positive, CD19-positive and NK cells count between patients with detectable and undetectable HEV RNA.

On regards to prognosis of subjects with chronic hepatitis E, adjustment of immunosuppression was only feasible in a limited number of individuals, though no changes in viral load were observed. However, therapy with Ribavirin achieved a persistent virological response in 50% of 6 the cases, rate lower than the 81% reported in a retrospective transplant cohort including 255 graft recipients.31

Although is well know the risk of HEV infection associated with some epidemiological factors such as consumption of game meat or raw/undercooked pig meat, and as also confirmed in our study, for the time being there is no recommendation on the international guidelines about the performance of HEV screening based on exposure features.1,32

However, and opposed to the screening recommendation, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) advise against the consumption of undercooked meat and shellfish for immunocompromised individuals.1

Our study has some limitations. Some groups of risk were underrepresented such as subjects with end-stage chronic kidney disease or HIV infection, though this fact can be partially explained by the tendency to low transaminases levels in these populations, especially those on hemodialysis. Moreover, the length of the study might also be considered a limitation, though this was a direct consequence of the difficulty for the recruitment of patients due to the strict inclusion criteria. Furthermore, we cannot completely explain why some individuals had elevated ALT in absence of detectable HEV-RNA because this was evaluated by each physician and was not among the aims of the study. Finally, information concerning risk-factors was collected by self-referred surveys, which can lead information bias. The main strengths are that this is a prospective and multicenter study where HEV markers were detected using the same reference laboratory, turning out interesting and important data on the importance of HEV infection on patients with immune impairment. Based on the results of our study we recommend to rule out chronic HEV infection in solid-organ transplant patients with increased transaminases values, especially if they are undergoing mTOR inhibitors.

In summary, the CHES study showed a prevalence of 1.6% of chronic hepatitis E among patients with immune dysfunction, with all viremic cases detected in solid-organ recipients. Immunosuppression with mTOR inhibitors was the only independent risk factor for chronic HEV infection.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. It was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Vall d’Hebron Hospital and the Spanish and European Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (PR(AG)29/2015 and protocol code REG-HEPE-2014-01, date of approval: 03/03/2017).

FundingThis work was supported and partial funding by a grant from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (grant number ICI14/00367).

Conflicts of interestNone.

The HEV RNA tests were supplied by Roche Diagnostics S.L. English language support was provided by Fidelma Greaves.