Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hepatitis C infection can be safely and effectively treated with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). However, there is scarce data on the long-term impact of hepatitis C cure on CKD. The aim of this study was to assess the long-term mortality, morbidity and hepatic/renal function outcomes in a cohort of HCV-infected individuals with CKD treated with DAAs.

Methods135 HCV patients with CKD stage 3b-5 who received ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir±dasabuvir in a multicenter study were evaluated for long-term hepatic and renal outcomes and their associated mortality.

Results125 patients achieved SVR and 66 were included. Prior to SVR, 53 were under renal replacement therapy (RRT) and 25 (37.8%) had liver cirrhosis. After a follow-up of 4.5 years, 25 (38%) required kidney transplantation but none combined liver–kidney. No changes in renal function were observed among the 51 patients who did not receive renal transplant although eGFR values improved in those with baseline CKD stage 3b-4. Three (5.6%) subjects were weaned from RRT. Eighteen (27.3%) patients died, mostly from cardiovascular events; 2 developed liver decompensation and 1 hepatocellular carcinoma. No HCV reinfection was observed.

ConclusionsLong-term mortality remained high among end-stage CKD patients despite HCV cure. Overall, no improvement in renal function was observed and a high proportion of patients required kidney transplantation. However, in CKD stage 3b-4 HCV cure may play a positive role in renal function.

Los pacientes con insuficiencia renal crónica (IRC) e infección por el virus de la hepatitis C (VHC) pueden ser tratados de forma efectiva y segura con antivirales de acción directa (AAD). El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la mortalidad y la evolución de la función renal y hepática a largo plazo en una cohorte de pacientes con infección por VHC e IRC tratados con AAD.

MétodosSe analizó la evolución de la función hepática y renal, así como la mortalidad en 135 pacientes con infección por VHC e IRC estadio 3b-5 que recibieron ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir±dasabuvir en un estudio multicéntrico.

ResultadosCiento veinticinco pacientes se curaron (RVS), y 66 de ellos fueron incluidos. Antes de RVS, 53 estaban bajo terapia renal sustitutiva (TRS) y 25 (37,8%) tenían cirrosis hepática. Tras un seguimiento medio de 4,5 años, 25 (38%) requirieron trasplante renal, pero ninguno combinado renal-hepático. No se observaron cambios en la función renal entre aquellos 51 pacientes que no recibieron trasplante renal a pesar de que los valores de eFGR mejoraron en aquellos pacientes con IRC estadio 3b-4 de base. Tres (5,6%) pacientes pudieron dejar la TRS. Dieciocho (27,3%) pacientes fallecieron, principalmente por eventos cardiovasculares, 2 presentaron descompensación hepática y uno carcinoma hepatocelular. No se observó ninguna reinfección por VHC.

ConclusionesLa mortalidad a largo-plazo fue alta. Globalmente no se objetivó una mejora en la función renal. A pesar de ello, en estadios 3b-4, la curación del VHC podría tener un papel positivo en la función renal.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects more than 70 million people worldwide.1 Although liver-related disease and its complications are the main cause of morbidity and mortality, extrahepatic manifestations can occur in up to three-quarters of cases.2 Furthermore, most data support that HCV-infected individuals are at a higher risk of renal disease than the general population. Although HCV-related nephropathy is uncommon, large evidence indicates that anti-HCV-positive individuals, especially those with viremic infection, are at a higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) and progressing to end-stage renal disease.3–5 In addition, increased liver-unrelated mortality, especially from cancer and cardiovascular events, has been described.6

Epidemiologically, the association between HCV and CKD is mainly due to exposure to the virus during dialysis or transfusion of blood derivatives. Furthermore, HCV infection can induce kidney disease by cytopathic and immune-mediated tissue damage.7 Immunoglobulin deposits can cause cryoglobulinemic nephropathy and membranoproliferative or membranous glomerulonephritis, which have been described classically as the major causes of HCV infection-related nephropathy.8 In addition to direct and indirect renal damage, genetic variables and cardiovascular comorbidities, the oxidative stress generated by chronic HCV infection leads to increased insulin resistance, a higher percentage of diabetes mellitus, and accelerated atherosclerosis contributing to increased cardiovascular risk.7 As a result, HCV itself has been proposed as an independent cardiovascular risk factor.9,10

The outcome of chronic HCV infection has radically changed since the introduction of direct acting antiviral (DAA) agents. The favorable safety profile and high rates of sustained virological response (SVR) have led to the view that hepatitis C elimination is a realistic objective in several geographical areas. It has been widely documented that the risk of liver-related complications and overall mortality decreases after SVR.11 Likewise, SVR achieves regression of fibrosis and even cirrhosis,12 and reduces the risk of most extrahepatic manifestations.13,14 In a large cohort of HCV patients with CKD treated with interferon-based regimens, the risk of end-stage kidney disease and death in those treated for at least 4 months was lower than that of untreated patients.15

DAA therapy is safe and highly effective in patients with CKD, end-stage renal disease, and those receiving renal replacement therapy (RRT).16 Data from a prospective study including 441 patients with chronic HCV infection and CKD (>30mL/min/m2) found that sofosbuvir-based regimens, old age, and advanced CKD were independently associated with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decline during therapy.17 In a retrospective case–control study including 523 HCV-CKD patients treated with DAAs, a smaller eGFR decline was seen in the treated group than in the untreated control group at 1 year of treatment, but these differences disappeared with longer follow-up.18 Overall, there is little data on long-term follow-up of patients with CKD treated with DAAs for chronic HCV infection.

The aim of this study was to assess long-term mortality and morbidity in a cohort of HCV-infected individuals with stage 3b-5 CKD who received ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir±dasabuvir (OBV/PTV/r±DSV) for 12–24 weeks, paying special attention to hepatic and renal function outcomes.

Patients and methodsThis is a multicenter, retrospective–prospective study including HCV-mono-infected or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-co-infected patients with HCV genotypes (GT) 1 or 4 and CKD stage 3b-5 who had previously participated in the Vie-KinD study. Patients had received OBV/PTV/r±DSV for 12–24 weeks between January and December, 2015.16 Baseline and SVR12 data were retrieved from the Vie-KinD study database. Patients with a previous renal transplantation were included if they were not undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Follow-up data were collected by a review of the patients’ medical records until December 2020. The data collected were clinical parameters such as hypertension, diabetes, CKD stage, renal replacement requirement, kidney transplantation, presence of cirrhosis, episodes of liver decompensation (ascites, variceal bleeding, and encephalopathy), hepatocarcinoma, and cause of death as well as blood tests and HCV-RNA load. The prospective part of the study focused on patients who were alive and available to follow up. They were contacted for a medical visit, and blood testing (including blood count, AST, albumin, bilirubin, creatinine, eGFR, and HCV-RNA) and transient elastography.

A historical cohort of HCV-infected individuals undergoing RRT (Catalan Transplant Organization [OCATT], 2000–2015) before the availability of DAA therapy was used to compare mortality rates.

The eGFR was calculated based on the CKD-EPI equation. The CKD stage was defined according to the KDIGO guidelines19: grade 1 ≥90mL/min/1.73m2, grade 2 ≥60–89mL/min/1.73m2, grade 3a ≥45–59mL/min/1.73m2, grade 3b ≥30–44mL/min/1.73m2, grade 4 ≥15–29mL/min/1.73m2, and grade 5 <15mL/min/1.73m2. Liver fibrosis assessment was performed by liver stiffness measurement (LSM), and fibrosis stage was classified as follows: F4 ≥12.5kPa, F3 ≥9.5, F2 ≥7, and F0–F1 <7kPa. HCV-RNA was determined using an automated real-time PCR system (Cobas 6800, Roche). Causes of death were classified into six groups (cardiovascular, cancer, infectious disease, kidney-related disease, liver-related disease, and others). This study was approved by the Vall d’Hebron Hospital Ethics Committee and the Spanish and European Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (code MMR-OMB-2020-01; date 03/04/2020) and was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice Guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. All participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study, and all data were anonymized.

Statistical analysisNormally-distributed quantitative variables were compared using the Student t test and expressed as median [IQR]. Variables with a non-normal distribution were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U test and expressed as the median and interquartile range or the range. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher exact test when frequencies were less than 5%, and expressed as frequencies and percentages. The 95% confidence interval of proportions was calculated using the Newcombe method.20 The results were considered statistically significant when the p-value was lower than 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS, 26 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA).

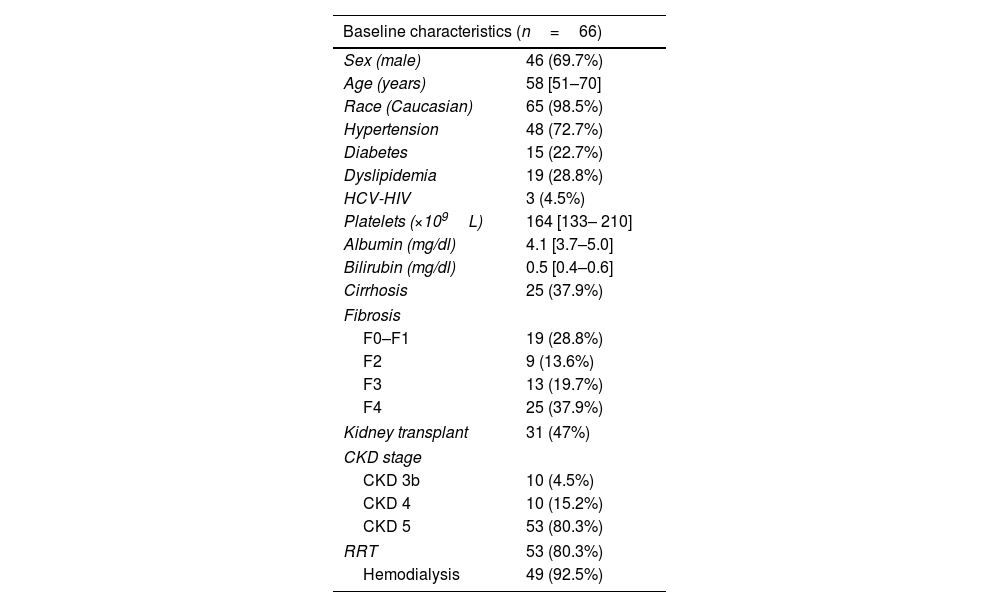

ResultsBaseline characteristicsOne hundred and thirty-five participants from 31 hospitals participated in the Vie-KinD study and 125 achieved SVR12. Sixty-six of those with a SVR were followed for more than 6 months and were included in the present study. The majority were men (69.7%), median age 58 [51–70] years, 98.5% Caucasians and 25 (37.9%) had liver cirrhosis, three of them with prior history of liver decompensation but compensated at the time of DAA therapy. The most common comorbidities were hypertension in 48 (72.7%), diabetes in 15 (22.7%), and dyslipidemia in 19 (28.8%). Three (4.5%) were HIV co-infected.

Concerning kidney disease, 3 (4.5%) had CKD stage 3b, 10 stage 4 (15.2%) and 53 (80.3%) stage 5. Fifty-three (80.3%) patients were receiving RRT, 49 (92.5%) were on hemodialysis and 4 on peritoneal dialysis. Thirty-one patients (47.0%) had history of previous kidney transplantation. The characteristics of the study patients at the time of DAAs initiation are summarized in Table 1. No changes in median creatinine and eGFR values were observed between baseline (prior to DAAs) and SVR12. Median creatinine and eGFR prior to DAA treatment were 5.6 [3.7–7.8]mg/dL and 10 [6.3–15.2]mL/min/1.73m2 and at SVR12 were 6.4 [4.3–8.3]mg/dL and 8 [6–16]mL/min/1.73m2, respectively.

Baseline characteristics at the time of entry in the long-term follow up after SVR.

| Baseline characteristics (n=66) | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 46 (69.7%) |

| Age (years) | 58 [51–70] |

| Race (Caucasian) | 65 (98.5%) |

| Hypertension | 48 (72.7%) |

| Diabetes | 15 (22.7%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 19 (28.8%) |

| HCV-HIV | 3 (4.5%) |

| Platelets (×109L) | 164 [133– 210] |

| Albumin (mg/dl) | 4.1 [3.7–5.0] |

| Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.5 [0.4–0.6] |

| Cirrhosis | 25 (37.9%) |

| Fibrosis | |

| F0–F1 | 19 (28.8%) |

| F2 | 9 (13.6%) |

| F3 | 13 (19.7%) |

| F4 | 25 (37.9%) |

| Kidney transplant | 31 (47%) |

| CKD stage | |

| CKD 3b | 10 (4.5%) |

| CKD 4 | 10 (15.2%) |

| CKD 5 | 53 (80.3%) |

| RRT | 53 (80.3%) |

| Hemodialysis | 49 (92.5%) |

† Values are expressed as the number and percent and median [IQR] unless otherwise specified.

‡ CKD: chronic kidney disease; RRT: renal replacement therapy.

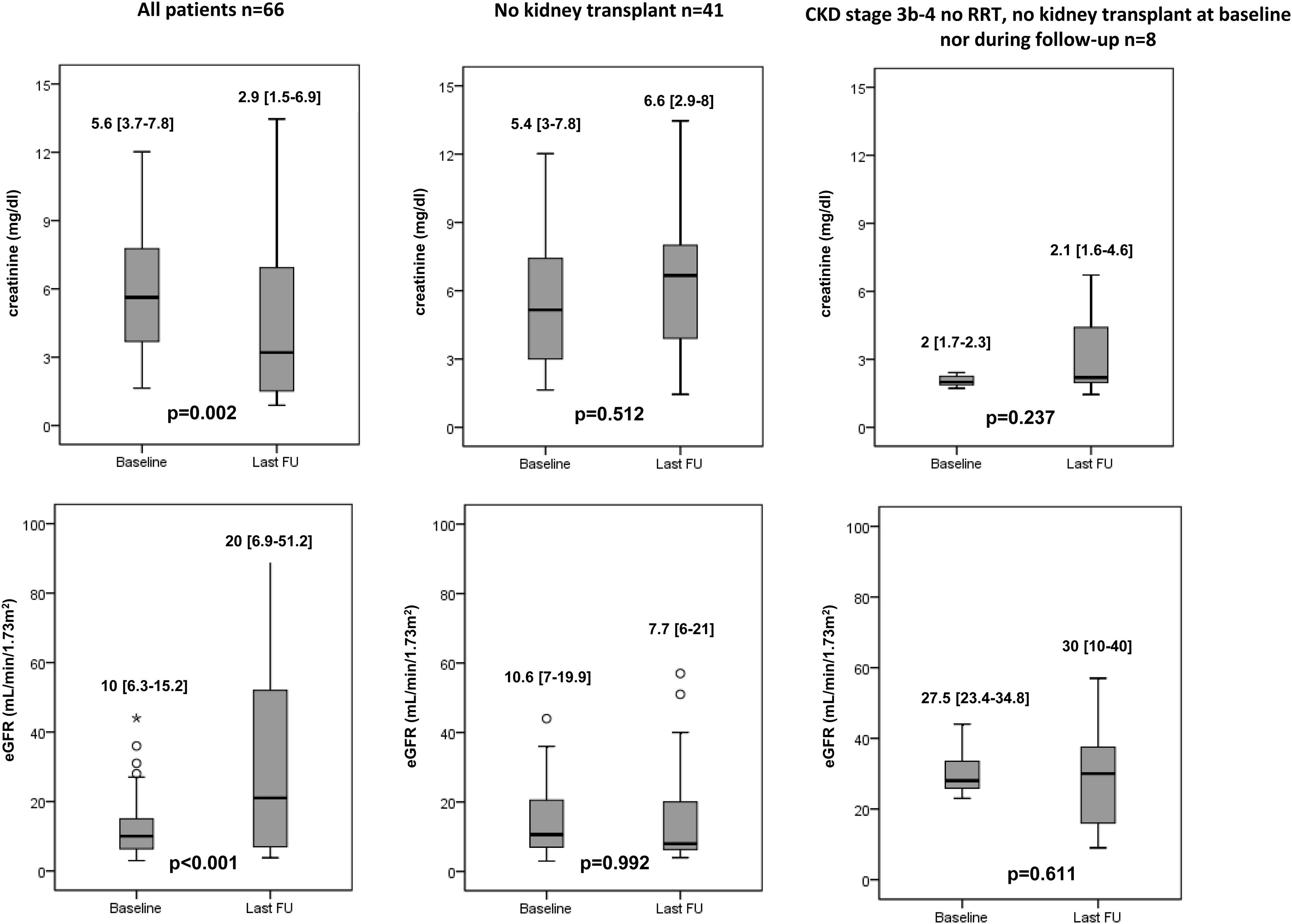

Twenty-five (37.9%) patients received a kidney transplant within a median period of 2.3 [0.9–2.8] years and all remained alive. None of them had HIV infection. Most of these patients (84.0%) had stage 5 CKD at the time of HCV therapy, and 19 (76.0%) were on dialysis. Despite the fact 7 (28.0%) of these patients presented liver cirrhosis, none required combined kidney–liver transplant. Overall, an improvement on serum creatinine (5.6 [3.7–7.8]mg/dL vs 2.9 [1.5–6.9]mg/dL, p=0.002) and eGFR values (10 [6.3–15.2]mL/min/1.73m2 vs 20 [6.9–51.2]mL/min/1.73m2, p<0.001) were observed after a median follow-up of 4.5 [3.7–5.1] years.

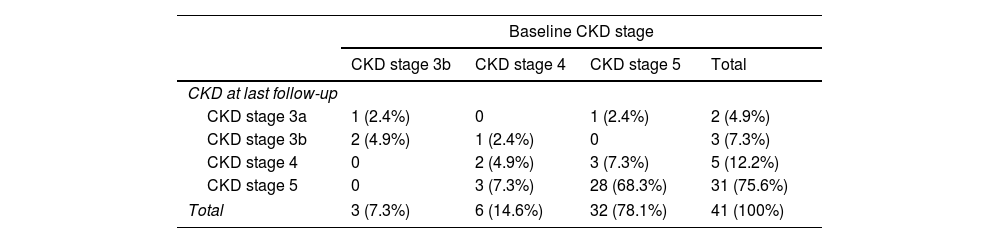

Among the 41 (62.1%) patients who did not undergo kidney transplantation, no changes in creatinine and eGFR values were observed during a median follow-up of 4 [2–5] years after DAA therapy (creatinine: 5.4 [3–7.8]mg/dL vs 6.6 [2.9–8]mg/dL, p=0.512; eGFR: 10.6 [7–19.9]mL/min/1.73m2 vs 7.7 [6–21]mL/min/1.73m2, p=0.992). However, CKD stage improved in 6 patients (14.6%) and worsened in 3 with prior CKD stage 4 (p<0.001) (Table 2). At last-follow up 35 patients were on RRT: 30 out of the 53 who were previously on RRT and 5 new patients who needed dialysis initiation. Renal function improvement led to discontinuation of RRT in 3 subjects, yielding a weaning rate from RRT of 5.6%. Finally, the 8 patients with baseline stage 3b-4 CKD had a slight increment in eGFR values over follow-up, although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 1).

Distribution of Chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage at baseline and last follow-up in the 41 patients who did not undergo kidney transplantation.

| Baseline CKD stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKD stage 3b | CKD stage 4 | CKD stage 5 | Total | |

| CKD at last follow-up | ||||

| CKD stage 3a | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 1 (2.4%) | 2 (4.9%) |

| CKD stage 3b | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | 0 | 3 (7.3%) |

| CKD stage 4 | 0 | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (7.3%) | 5 (12.2%) |

| CKD stage 5 | 0 | 3 (7.3%) | 28 (68.3%) | 31 (75.6%) |

| Total | 3 (7.3%) | 6 (14.6%) | 32 (78.1%) | 41 (100%) |

CKD stages at baseline and last follow-up of the 41 patients who did not undergo kidney transplantation; 1 (2.4%) patient was CKD stage 3b at baseline and stage 3a at LFU, 1 (2.4%) was CKD stage 4 at baseline and 3b at LFU, 1 (2.4%) was CKD stage 5 at baseline and 3a at LFU, and 3 (7.3%) were CKD stage 5 at baseline and stage 4 at LFU. The CKD stage worsened in 3 (7.3%) patients who were stage 4 at baseline and progressed to stage 5 at LFU.

† Values are expressed as the number and percent.

‡ CKD: chronic kidney disease; LFU: last follow-up.

During follow-up, 2 (5.3%) patients with baseline compensated cirrhosis developed liver decompensation (ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, respectively). In addition, 1 (2.6%) patient with liver cirrhosis developed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) within the first year after achieving SVR. None of them had HIV infection. None of the patients required liver transplantation. The only patient who died from liver disease was cirrhotic at baseline and died due to liver failure. In 51 subjects HCV-RNA was performed during follow-up (39 during the last visit and 12 additional patients within the prospective check-up) and no cases of reinfection were observed.

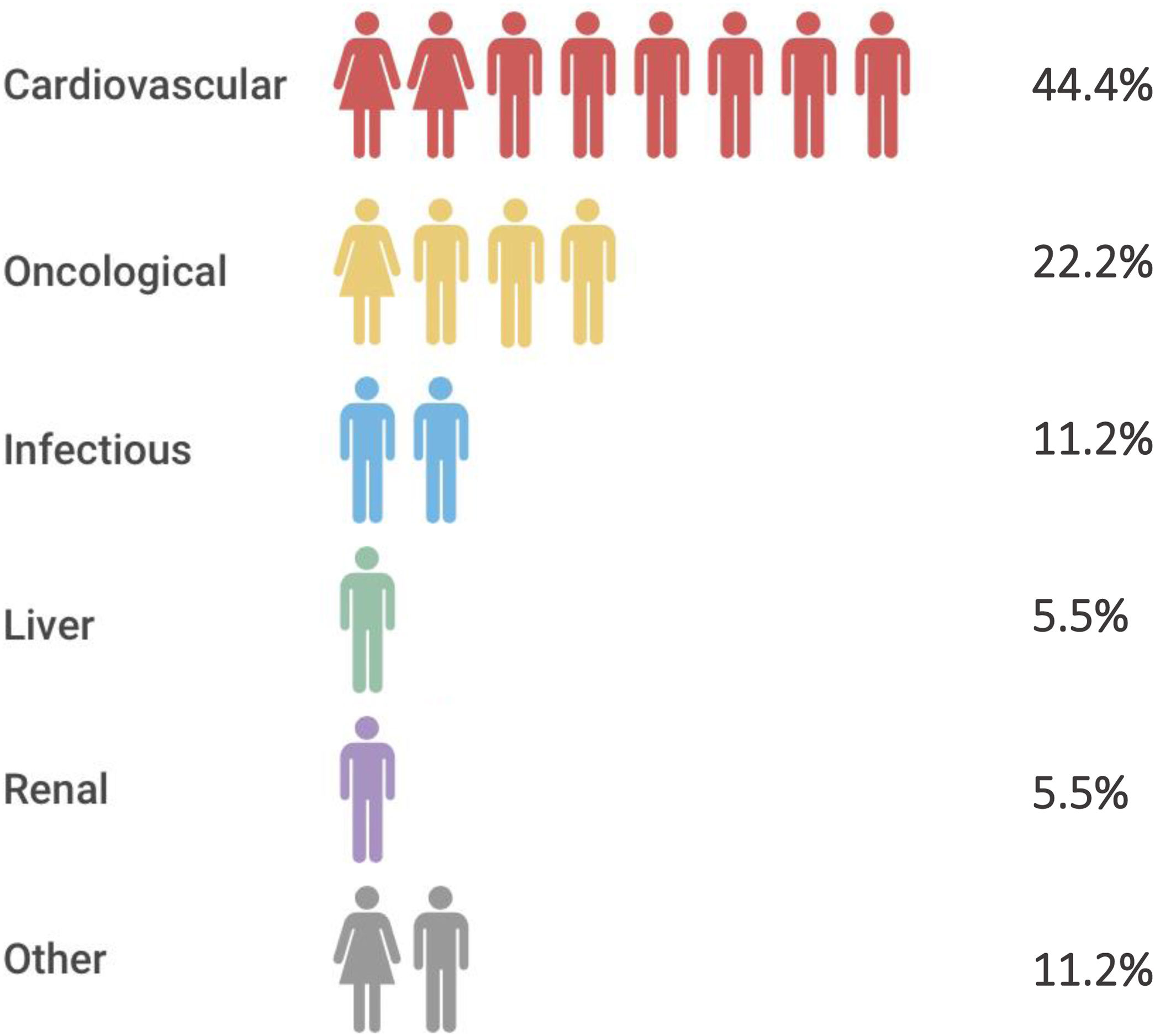

Overall mortality and comparison of mortality rates with a historical cohort of CKD patientsEighteen (27.3%) patients, most of them receiving RRT (16, 88.9%), died during a median follow-up of 4.5 [3.7–5] years. None of them had HIV infection. Main causes of mortality are shown in Fig. 2. The mortality rate among the 53 patients receiving RRT at baseline was 26.4% and 30.8% in those without RRT (p=0.5). Mortality among the 30 patients who remained on RRT during the total follow-up was 40.0%. All-cause mortality in cirrhotic patients (44.0%) was higher than in non-cirrhotic ones (17.1%) (p=0.02).

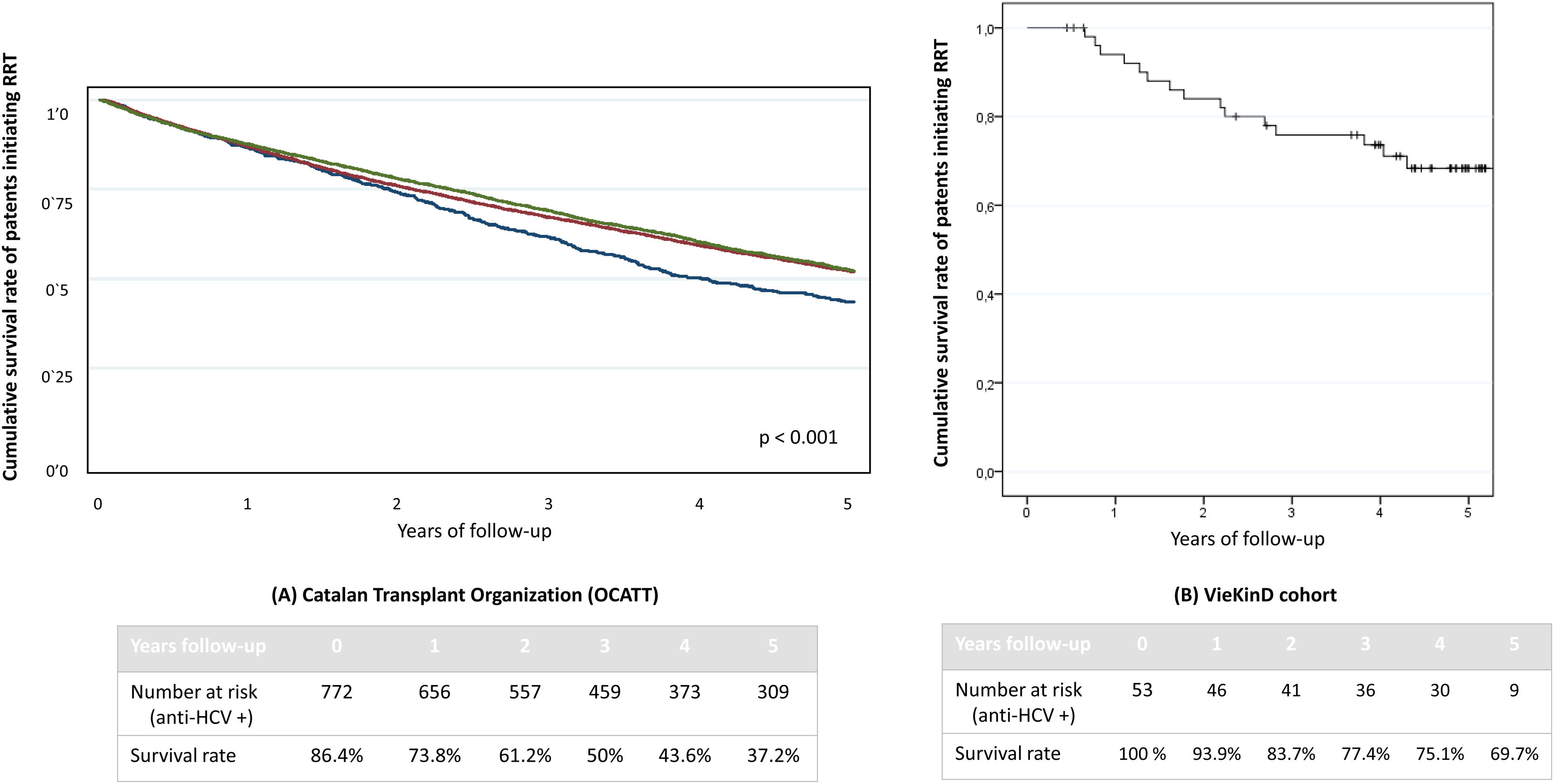

Over a median follow-up of 4.3 years [2.7–4.9] the survival rate of our cohort of 53 HCV patients undergoing RRT was compared with the one from an historical cohort from the Catalan Transplant Organization (OCATT) including 16,834 patients who began RRT between 2000 and 2019. This cohort included 772 anti-HCV positive patients who initiated RRT between 2000 and 2015. No data on the percentage of HCV viremic patients could be retrieved. No differences in survival rate were observed among those anti-HCV negative who initiated RRT between 2000 and 2010 and those who began between 2011 and 2019, though it was greater than observed among anti-HCV positive subjects (p<0.001), as shown in Fig. 3. For comparison with our cohort, only the 53 patients who were on RRT before DAAs therapy were included. The four-year survival (median follow-up duration) in this group of patients was 75.1%, significantly higher than that reported in the HCV-positive cohort from the OCATT (75.1% vs 43.6%. p<0.001).

Comparison of survival rate with a historical cohort of patients with CKD. (A) OCATT five-year survival rate of three cohorts of patients undergoing renal replacement therapy. Blue line refers to anti-HCV positive patients who initiated renal replacement therapy (RRT) between the year 2000 and 2015. Red line corresponds to anti-HCV negative patients who initiated RRT between the years 2000 and 2010 and green line to anti-HCV negative patients who initiated RRT between the years 2011 and 2019. As we can see, anti-HCV positive (blue) patients have a significantly lower survival rate than both anti-HCV negative cohorts (red and green lines). (B) VieKinD five-year survival rate of the 53 patients who were under renal replacement therapy prior to initiation of DAA therapy.

† CKD: chronic kidney disease; OCATT: Organització Catalana de Transplantaments; RRT: renal replacement therapy; DAA: direct-acting antiviral.

Twenty-four (36.4%) patients (14 men and 10 women) came to an additional medical appointment and blood test were performed. Median follow-up of this cohort was 5.3 [4.9–5.4] years. Fourteen patients received kidney transplantation. Among the 10 patients who did not undergo transplantation, 8 had CKD stage 5 before DAAs and showed no renal function improvement during follow-up. In the remaining 2 patients, both CKD stage 3b at baseline, CKD stage improved to stage 1 and 2, respectively (p=0.2). LSM was performed in 19 subjects, showing a significant improvement in liver fibrosis (follow-up 6.2 [5–10.1]kPa vs 9.7 [6.1–14.4]kPa at baseline, p=0.027). From the 12 subjects with baseline LSM of advanced fibrosis, just six (50%) continued with LSM >12.5kPa at the prospective appointment. None of these 24 patients presented HCV reinfection.

DiscussionTo our knowledge this study has the longest follow-up of HCV-infected individuals with advanced CKD treated with DAAs. CKD is a complex condition, and numerous factors are involved in its progression and outcomes. Hence, estimating the impact of HCV clearance in this scenario is a challenging task, especially in advanced stages of kidney disease. Our results showed trends to an eGFR improvement in patients with stage 3b-4 CKD at baseline, but not in those with end-stage CKD, the vast majority of patients included in the cohort. Although the overall results showed an improvement of renal function (creatinine and eGFR) at last follow-up, this is mostly due to the increase in eGFR and decrease in creatine values experienced amongst those patients who received a kidney transplant. A more realistic assessment of our results is that renal function did not improve in the 41 patients who did not receive a kidney transplant, although 3 (9.1%) patients were able to discontinue RRT and 6 (14.6%) showed an improvement in the CKD stage. In comparison to our observations, the results from a cohort of 523 CKD-HCV patients followed for 1 year after DAA treatment showed a smaller eGFR decline in those who achieved SVR12, although this decline was not different when compared to an untreated historical HCV-CKD cohort.18 Likewise, an improvement in eGFR from baseline to 12 weeks post-therapy was described in 403 HCV-infected individuals, with or without CKD. In that study, a greater eGFR improvement was found among patients with baseline eGFR below 30mL/min/1.73m2.21 Similarly, regression models from short-term follow-up of DAA-treated CKD-HCV-infected individuals showed that HCV cure was associated with a 9.3mL/min/1.73m2 improvement in eGFR during the 6 months after treatment.22 However, these studies are heterogeneous and not entirely comparable to the present study because they did not include patients with end-stage CKD, which could easily explain the overall differences relative to our observations. Older age and male sex have been linked to kidney disease progression; median age at baseline in our cohort was approximately 60 years and almost two-thirds were men. We found no significant improvement in cardiovascular comorbidities after HCV elimination, and unfortunately, we were unable to evaluate the prevalence of cryoglobulinemia, at baseline or during follow-up, nor the changes in proteinuria as a marker of CKD progression because consistent data were not retrieved. Thus, based on our results, we believe that HCV clearance has a positive impact on renal function, but this effect seems to be minimal or nonexistent in patients with end-stage CKD due to the advanced renal damage.

Liver decompensation and HCC development were uncommon after DAA treatment in our patients, even though approximately 60% of them had advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, in most cases compensated at baseline. It is relevant to mention that none of the transplanted patients required a combined transplant (kidney–liver). It has been amply demonstrated that achieving SVR reduces the risk of liver-related mortality and disease progression. In a recent study including 869 HCV patients treated with DAAs, the risk of clinical disease progression after a long-term follow-up was reduced in Child–Pugh A patients, but not in Child–Pugh B/C.23 Similarly, results from long-term follow-up of 1760 HCV patients showed a significant decrease in all-cause mortality and liver-related complications. Although some patients had such complications, the annual incidence rate (4.1%) was lower than the expected rate documented during the natural history of HCV.11 In our cohort, liver-related complications occurred in 5.3% of patients and HCC in almost 3%. All these patients had advanced liver fibrosis prior to DAA and one had experienced liver decompensation prior to DAA therapy. Regarding the HCC diagnosis, it is important to note that it was diagnosed during the first year after DAA treatment (10 months after). Data from a prospective follow-up of a large cohort of HCV patients treated with DAAs or IFN showed that HCC development after DAA treatment had a 3-year crude incidence of 5.9%, which reached its maximum and stabilized at 1 year after the end of treatment.24 Although HCV cure stops progression of liver disease, fibrosis regression can take years.25 Thus, the risk of decompensation or HCC, although decreased, remains high in advanced fibrosis stages, especially in patients with decompensated cirrhosis at baseline, and this could be the reason for the liver-related events observed. In addition, and related to fibrosis regression, a significant improvement in LSM measurement was seen in the prospective evaluation. Although there is evidence supporting the lack of correlation between post-SVR LSM and fibrosis stage, a recent study has described a risk reduction of liver related complications and death in those patients whose LSM measurement decreased more than 20% after SVR.26

Furthermore, our cohort included a high percentage of patients with diabetes, hypertension or dyslipidemia, making it difficult to rule out nonalcoholic fatty liver disease as a coexistent etiology for the liver disease progression. In that sense, data from a retrospective study including more than 33,000 HCV patients treated with DAAs reported an increased risk of mortality and liver decompensation among patients with diabetes.27 Finally, no cases of documented HCV reinfection were detected among the 51 patients who had a currently available HCV-RNA determination during follow-up reflecting the improvement in universal precautions and in dialysis and blood transfusions.

Mortality was high in our cohort (27.3%), especially among patients undergoing RRT. It is well recognized that patients on RRT are at a higher risk of death than the general population, especially those receiving hemodialysis.28 Cardiovascular disease is the main cause of death in this population. Although several studies have shown an increased overall risk of cancer in patients with end-stage CKD, there is still some controversy in this line.29 A retrospective study including more than one million adults concluded that eGFR decreases are independently associated with a higher risk of renal and urothelial cancer, but not with other cancer types.30 In our cohort, cardiovascular events and cancer (2 lung, 1 colorectal and 1 breast cancer) were responsible for more than 50% of deaths and mortality was significantly higher in cirrhotic patients. Finally, survival rate of our patients receiving renal replacement therapy was significantly higher than those observed in OCATT's cohort despite the fact the sample sizes are not comparable and the lack of some sensitive information such as the number of viremic patients. Nevertheless, in Spain, DAA therapy was not universally available before 2015 and many HCV patients were not treated, including those with end stage renal disease. Thus, we assumed that a significant number of anti-HCV-positive patients from OCATT's cohort would be viremic at that point, which could reasonably explain the survival rate differences observed in our study.

The main limitations of our study are the predominant retrospective nature of the data and the relatively small proportion of patients from the VieKinD cohort who were followed and were able to be included. In this sense, information of some of the remaining patients included in the ViekinD cohort could not be retrieved by some health-care units due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the high percentage of patients with end-stage CKD or undergoing RRT may have prevented us from observing a significant improvement in renal function after the long-term follow-up. As a counterpart to these limitations, this is a multicenter study including patients from 31 hospitals in Spain with a lengthy follow-up after DAA treatment.

In summary, mortality is high in end-stage CKD HCV patients treated with DAAs, mainly due to cardiovascular events and cancer. Overall, renal function did not improve after HCV treatment, but a slight, non-significant improvement in the eGFR was seen in patients in stage 3b-4 at baseline. Liver decompensation and hepatocarcinoma were infrequent, even though a large percentage of patients had advanced fibrosis.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approvalThe study was designed, implemented and reported in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. The study was approved by the ethics committee of all participating centers and by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (MMR-OMB-2020-01).

Conflict of interestJoan Martínez-Campreciós: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Mar Riveiro-Barciela: MRB has received research educational and/or travel grants from Gilead and has served as a speaker for Gilead and Grifols.

Raquel Muñoz-Gómez: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

María-Carlota Londoño: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Mercé Roget: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Miguel Ángel Serra: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Desamparados Escudero-García: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Laura Purchades: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Manuel Rodríguez: MR has served as an advisor/lecturer for Gilead and Abbvie.

Juan E. Losa-García: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

María L. Gutiérrez: MLG reports collaboration with Gilead and Abbvie.

Isabel Carmona: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Javier García-Samaniego: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Luís Morano: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Ignacio Martín-Granizo: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Marta Montero-Alonso: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Martín Prieto: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Manuel Delgado: MD reports ABBVIE funding for scientific advice and continuing medical education

Natalia Ramos: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

María A. Azancot: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Francisco Rodríguez-Frías: The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Maria Buti: MB has served as speaker and advisor for Gilead and Abbvie.

![Median creatinine and eGFR at baseline and last-follow up visit. † Values are expressed as median [IQR]. ‡ eGFR (estimated). Median creatinine and eGFR at baseline and last-follow up visit. † Values are expressed as median [IQR]. ‡ eGFR (estimated).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/02105705/0000004600000008/v1_202309280830/S0210570522003132/v1_202309280830/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)