Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) has become one of the most severe mental health problems among adolescents and young adults worldwide, especially in clinical populations. The main objective of this non-randomized pilot study is to demonstrate the effectiveness of the TaySH Program in a clinical sample of 37 outpatients aged 14 to 25 years (M = 16.70, SD= 1.51), TAY (Transitional age youth) developmental stage.

MethodsAll participants underwent the baseline or pre-treatment assessment and 28 patients completed the 12-week intervention treatment and underwent post-treatment evaluation through different interviews and self-reports. The primary outcome was the reduction of NSSI, and the secondary outcomes were suicide risk, emotional dysregulation, the psychopathological clinical manifestations of impulsivity, depressive symptoms and anxiety, and psychosocial functioning.

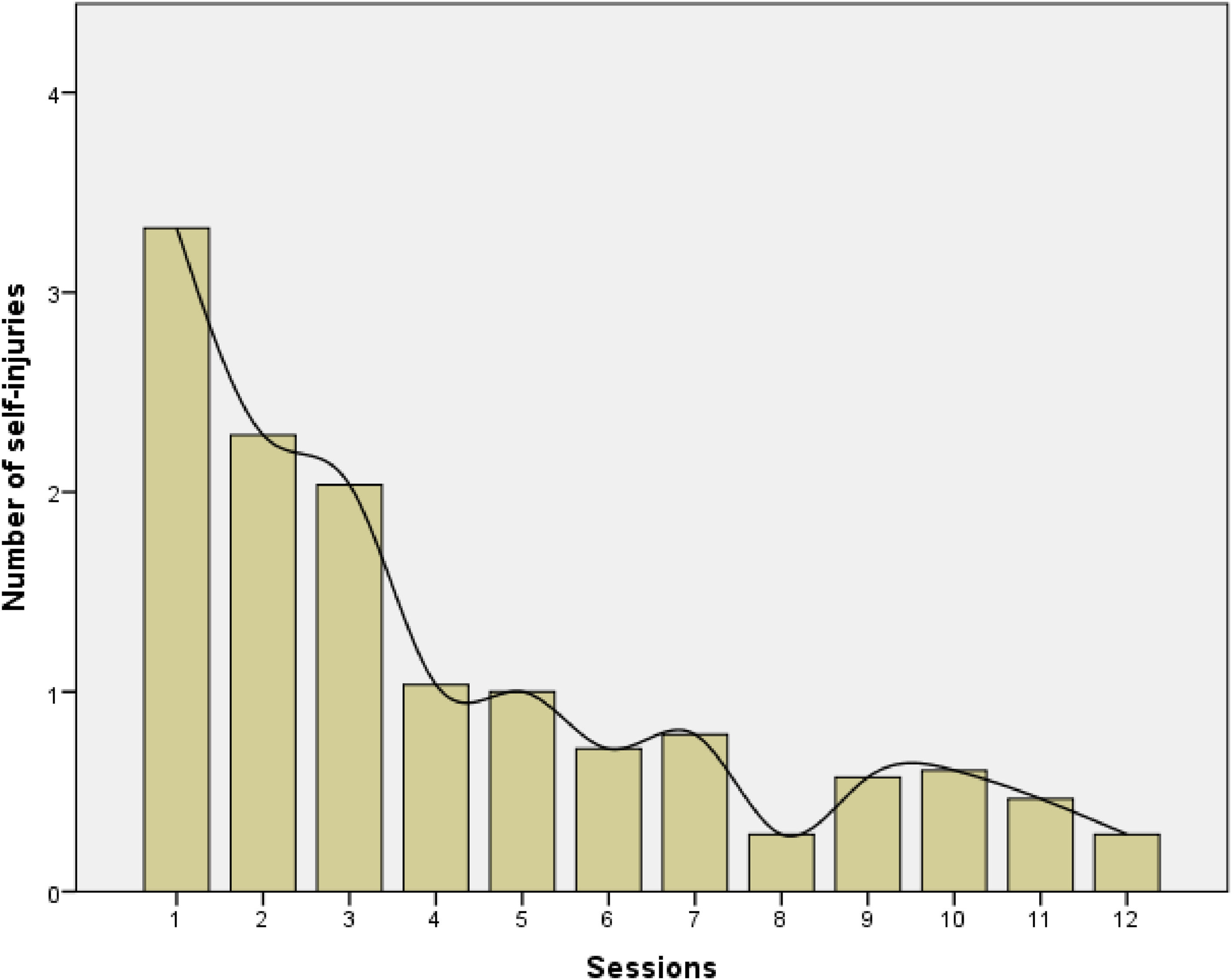

ResultsThe frequency of NSSI behaviors decreased significantly from a mean of 3.32 (SD=4.07) episodes per week at baseline to 0.29 (SD=0.98) episodes per week post-treatment (p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 0.458). This reduction was accompanied by an improvement in associated psychopathological symptoms, leading to better psychosocial functioning among program participants.

ConclusionsThe results suggest that the TaySH Program is a promising early intervention for managing NSSI in this population. Future studies should examine the maintenance of the changes achieved, especially concerning the reduction of the psychopathology's tendency toward chronicity.

Las conductas autolesivas no suicidas (NSSI) se han convertido en uno de los problemas de salud mental más severos entre adolescentes y adultos jóvenes del mundo, especialmente entre poblaciones clínicas. El principal objetivo de este estudio piloto no aleatorizado es demostrar la efectividad del Programa TaySH en una muestra clínica de 37 pacientes ambulatorios de entre 14 y 25 años (M = 16.70, SD = 1.51), en la etapa de desarrollo TAY (Transitional age youth).

MétodosTodos los participantes realizaron la evaluación baseline o pre-tratamiento y 28 de ellos completaron la intervención de 12 semanas y realizaron la evaluación post-intervención. Se tomaron como resultado principal la reducción de las conductas autolesivas, y como secundario el riesgo suicida, la desregulación emocional, la clínica psicopatológica de impulsividad, de síntomas depresivos y ansiedad, y funcionamiento psicosocial.

ResultadosLa frecuencia de las conductas de NSSI disminuyó significativamente, pasando de una media de 3.32 (SD=4.07) episodios por semana a 0.29 (SD=0.98) episodios por semana tras la intervención (p < 0.001, d de Cohen = 0.458). Esta reducción fue acompañada por una mejora en los síntomas psicopatológicos asociados, lo que llevó a un mejor funcionamiento psicosocial entre los participantes del programa.

ConclusionesLos resultados sugieren que el Programa TaySH es una intervención temprana prometedora para el manejo de las NSSI en esta población. Futuros estudios deberían estudiar el mantenimiento de los cambios conseguidos especialmente en relación a la reducción de la tendencia a la cronificación de la psicopatología.

Non-suicidal self-harm (NSSI) is a recurrent and increasing risk behavior, especially among adolescents and young adults, and is considered a severe public health problem.1 NSSI behaviors are defined as intentional self-inflicted damage to the surface of the body, such as cuts, burns, stabbing, blows, and excessive rubbing, with the expectation that the injury will result in minor or moderate physical harm and in the absence of suicidal intent.1,2 Self-cutting is the most frequently chosen method of self-injury across different studies, although individuals usually use more than one method to self-injure.3,4,5

NSSI occurs in a variety of mental disorders, primarily Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) and adolescent affective disorders. NSSI is associated with a significant deterioration in these patients’ psychosocial functioning and quality of life.6,7,8 Its relevance is such that the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th ed. Revised (DSM-5-TR) has included it as a novelty in Section II under the section “Other problems that may be the subject of clinical attention,” as Non-Suicidal Self-Harm Disorder (NSSID).9

In the last decade, the prevalence of adolescents with NSSI in the general worldwide population has been in the range of approximately 16 to 22% of adolescents, according to some studies,10,11,12 with a significantly higher prevalence in girls than in boys (19.4% and 12.9%, respectively, or risk ratio 1.72) .13 It is exhibited by 50 – 60% of this population in simple clinical studies, with prevalences that can reach 80% depending on the studies.14,15 Its onset is in early adolescence; it begins mainly in early adolescence, especially between ages 12 and 14,3 and peaks in late adolescence9,16 These data indicate the great impact of these behaviors during the developmental stage that goes from adolescence to early adulthood.17 The latest studies indicate that this stage coincides with what some authors have begun to call the Transitional Age Youth (TAY), a period of transition that begins around ages 15 - 16 and persists beyond 25 years, thus including the two classic groups of “adolescence” or “young adults,” which have been established according to arbitrary and non-evolutionary criteria and may be rigid and artificial.18,19

On the other hand, the frequency and diversity of NSSI methods vary widely among patients, and some studies indicate that they are crucial for determining the severity of the behaviors during their assessment and for subsequent intervention.15,20,21 Therefore, severity assessment should be made in terms of frequency and versatility, understood as the number of methods used to self-harm.22

Prospectively, NSSI is an important predictor of suicidal behavior, as well as of long-term mortality.23 Therefore, despite the lack of intention to die, NSSI is a risk factor and the strongest predictor of eventual death by suicide, with prevalences of comorbidity between NSSI and suicide in clinical populations reaching 70% of cases.24-28 Maintenance of such behavior has been associated with a higher risk of suicide ideation.29 Previous research has indicated that the increased risk of suicide attempts is highly related to greater frequency, more methods, and longer duration of NSSI.10,28 Repetitive engagement in NSSI in adolescence has also been associated with an increased probability of partaking in risk-taking behaviors and developing mental health problems, as well as continuing to use dysfunctional strategies to achieve emotional regulation,30 and psychological impairment,31 and a later diagnosis of BPD.16,29 Therefore, the reduction of NSSI is associated with a decrease in suicidal behavior, a fact that underlines the need for specific interventions.23,32

Cross-sectionally, NSSI may be associated with greater difficulty in controlling emotions, that is, with severe emotion dysregulation and also with a wide range of comorbid diagnoses.23,32,33 In this context, NSSI should be understood as a means to reduce or change negative emotional distress (as risk-taking behaviors characterize this phase), thus considering the presence of negative affect as a strong predictor of NSSI.9,34-36 In this context, NSSI has become a serious global public health problem of concern to clinicians and society.13,15 All this implies that NSSIs are heterogeneous and vary between individuals due to their frequency, method, severity, and functionality, showing different clinical expressions and with variability in the risk factors and associated psychiatric comorbidity.37 However, the results presented to date do not allow us to conclude the existence of clearly differentiated subtypes.

Despite this social alarm due to the severity of the psychopathological symptoms and the deterioration of psychosocial functioning described as associated with repetitive NSSI, most affected adolescents and young adults do not receive adequate treatment23 In general, these patients tend to be reluctant to ask for help and seek treatment because of the stigma associated with these behaviors.38 Remarkably, although recent studies have revealed that psychological approaches are the main treatment of choice for the approach and management of NSSI,17,39,40 specific therapeutic options are very scarce.23 Nonetheless, some of the psychotherapies with the most scientific evidence have been adapted to the adolescent population (Dialectical Behavior Therapy -Adolescent; DBT-A, Mentalization-based Therapy-Adolescent; MBT-A) .41,42 All of them understand NSSI as one more symptom of a broader psychopathological picture, but not as the main psychotherapeutic objective.39 Over the past 10 years, coinciding with the increased prevalence of NSSI in youths and the increase in research and the new proposal for the diagnosis, several specific psychotherapeutic interventions focusing on NSSI have been specifically designed to be used to reduce NSSI and prevent evolution towards more severe psychopathological conditions.16 According to a recently published review16 of the 6 existing psychotherapeutic programs, only 2 have been studied to demonstrate their efficacy in reducing NSSI, as well as in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms using randomized controlled trials (RCT): The Cutting Down Program (CDP)43 and the Treatment for Self-Injurious Behaviors program (T-SIB) .44 More recently, a new treatment program, Cut the Cut (CTC) ,45 has been published as a pilot study for adolescent inpatients with NSSI. In general, most of these programs have in common a series of therapeutic elements that seem to guarantee their effectiveness, such as psychoeducation, alternative behavioral skills, and problem-solving strategies; they target relationships or interpersonal functioning, particularly within the family, including family or parents in treatment; they are intensive and they address further maladaptive behavior, as well as risk factors for NSSI, such as depression or substance abuse.46 However, the effects of these interventions have been poorly studied.

Within this clinical field, in view of the absence of these programs in our clinical environment, in the Mental Health Service of the Hospital Vall d'Hebrón of Barcelona (Spain), we have developed a new comprehensive psychotherapeutic intervention program for high-risk patients with NSSI, as well as associated risk behaviors: the Psychotherapeutic Intervention Program for Non-Suicidal Self-Harm for Adolescents and Young Adults, TaySH Program,18 to fill this gap. This program is specifically designed to address and manage these behaviors. Unlike most of the previously mentioned programs, it targets patients in the TAY evolutionary period. Its design and brevity, as well as its evidence-based content grounded in the models of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), its involvement of the family environment, and the complementary psychopharmacological treatment in those cases where it is required, aim to reduce the frequency of NSSI and improve the associated psychopathology and maintain the therapeutic changes obtained over time. The TaySH Program draws on key elements of both CBT and DBT, as these approaches have demonstrated efficacy in addressing NSSI.17 This integration of CBT and DBT is designed to specifically address the complex emotional and cognitive challenges faced by adolescents and young adults with NSSI, offering a structured yet flexible approach that is adapted to their developmental stage. From CBT, the focus on identifying and restructuring maladaptive thoughts and behaviors plays a critical role in understanding the function of self-injury as a maladaptive coping strategy. DBT, on the other hand, provides essential strategies for emotional regulation and distress tolerance.

This work is a pilot study whose main objective is to examine the effectiveness of the TaySH Program applied individually in an outpatient setting. Its primary outcome is the reduction of the number of NSSIs, and the secondary outcomes are to measure the risk of suicidal behaviors, in the clinical manifestation of emotional dysregulation and impulsivity, depressive symptomatology and anxiety, and psychosocial functionality.

Material and methodsParticipantsA total of 37 participants were included in the study, attended to between March 2023 and January 2024 in the outpatient clinics of the Mental Health Service of the Hospital Vall d'Hebrón (Barcelona, Spain). The main reason for consultation was the NSSIs presented in the last 12 months: self-harm on 5 or more days with the idea of self-inflicting minor or moderate physical harm, without the intention to commit suicide (DSM-5-TR) as the main psychopathology, causing impairment of psychosocial functioning.

We used the following inclusion criteria: 1) being between 14 and 25 years of age, a stage considered the transition from adolescence to early adulthood (TAY); 2) absence of active suicidal ideation; 3) absence of DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for psychotic spectrum disorders, bipolar spectrum disorders, substance use disorders, autism spectrum disorders; 4) absence of serious or chronic disabling medical conditions, including those of a sensory nature that preclude evaluation or treatment; 5) IQ higher than 80; and 6) not be undergoing any parallel naturalistic psychotherapeutic intervention in the course of the study.

All patients who met the inclusion criteria were consecutively invited to participate, and all of those invited agreed to do so. This high initial acceptance rate could suggest a strong interest in the TaySH Program, potentially reflecting an unmet need for targeted interventions within this population.

Study design and participantsThe design of this pilot study was a non-randomized, quasi-experimental study with a pretest-posttest for one group. A non-randomized design was chosen due to the ethical considerations of withholding potentially beneficial treatment from high-risk individuals with NSSI. Given the severe nature of NSSI and the associated risk of progression to suicidal behaviors, offering the TaySH Program to all eligible participants was prioritized. This design also allowed for the preliminary evaluation of the intervention's effectiveness in a naturalistic clinical setting, providing valuable data to inform future randomized controlled trials. The study was approved by the Committee of the Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebrón, Spain, CEIm of the HUVH Code PR (AG) 312/2023.

All patients underwent a baseline psychopathological evaluation (pre-treatment) before starting the TaySH Program and another evaluation at the end of it (post-treatment). The psychopathological assessment of the patients was done through three consecutive visits to a psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist, both with extensive clinical experience of NSSI. In the first visit (with the psychiatrist), clinical and sociodemographic data were collected, and clinical interviews were conducted. During the second and third visits, the clinical psychologist administered the clinical and psychometric tests established for the study. The aim of this pre-treatment evaluation was to assess the presence of NSSI and its associated severity, especially the risk of suicidal behaviors, the presence of psychopathological criteria and/or psychopathological personality traits, depressive and anxious psychopathological symptoms, and the degree of psychosocial dysfunction. The instruments are described in Instruments section.

After the diagnostic evaluation, the patients who were eligible for the Program and their parents or legal guardians were informed about the TaySH Program and were invited to participate on a completely voluntary basis. All were informed of the study and agreed to be included. They gave written informed consent for participation prior to their inclusion in the study. In the case of underage patients, the informed consent was signed by their parents or legal guardians.

Once the TaySH Program was completed, the post-treatment psychopathological evaluation was carried out by the same clinical psychologist in an individual visit.

TaySH programThe TaySH Program is a short, weekly, individual program. It is structured into 4 basic modules that include the 12 sessions, whose therapeutic objectives are clearly differentiated. Its main purpose is the identification, management, and reduction of problem-behaviors based on their use for their subsequent generalization, through adaptive and functional strategies and skills such as psychoeducation, identification of the factors that trigger and maintain this problem-behavior, emotion regulation, skills-training in alternative behavioral and problem-solving strategies. All the material is included in the “Intervention Manual for the patient” that is delivered at the beginning of the treatment for the patient to keep and work on daily both in the sessions and at home. In addition, the patient should keep a weekly log that allows the therapist to monitor NSSI and other risk behaviors, and use the material to assess their progress. At the same time, three psychoeducational sessions are held for the patient's parents or legal guardians ("Guide for parents and caregivers”). If complementary psychopharmacological treatment is required, both the visits made and the type and regimen of the indicated drug will be recorded. For more information, see the original Manual.18

InstrumentsThe instruments used for the baseline diagnostic evaluation (TaySH pre-treatment) in the Spanish version can be grouped according to their purpose:

- •

Presence of Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behaviors and their functionality, and clinical severity and/or associated psychopathological traits of emotional or personality dysregulation: ISAS, DERS, PID-5-SF, BPFSC-11, BPS, BPD Checklist, and SR.

ISAS (Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury)47,48 This scale evaluates NSSI and its functions through 13 categories: affective regulation, interpersonal boundaries, self-punishment, self-care, anti-dissociation, anti-suicide, sensation-seeking, peer relationships, interpersonal influence, toughness/resistance, emphasizing stress, revenge, and autonomy.

DERS (Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale)49,50 This self-report assesses emotion-regulation capacity according to 5 factors: lack of emotional attention, emotional confusion, emotional rejection, life interference, and emotional lack of control. High scores indicate greater difficulties in emotion regulation.

PID-5-SF (Personality inventory for DSM-5- Short Form) .51,52 This self-report assesses psychopathological personality traits of Section III of the DSM-5-TR using 5 Domains (negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychoticism) and their corresponding 25 Facets.

BPFSC-11 (Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children) .53,54 This scale measures borderline personality traits in children over 9 years of age and in adolescence.

BPS (Borderline Pattern Scale for the ICD-11) .55 This self-report assesses BPD symptomatology following the ICD-11, using 4 scales: Affective Instability, Maladaptive Self-Functioning, Maladaptive Interpersonal Functioning, and Maladaptive Regulation Strategies.

BPD Checklist (Borderline Personality Disorder Checklist) .56,57 This evaluates BPD symptoms of the DSM during the month prior to the test.

SR (Suicide Risk) .58,59 This scale assesses suicide risk based on previous suicide attempts, current ideation, feelings of depression and hopelessness, and other aspects related to attempts.

- •

Associated clinical symptoms and degree of functional impairment: CTQ, BDI-II, STAI, BIS-11, FAST

CTQ (Childhood Trauma Questionnaire) .60,61 Self-report to assess traumatic childhood experiences of emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect.

BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory- Second Edition) .62,63 This self-report measures the presence and severity of clinical depression in the last two weeks.

STAI (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory) .64 This is a self-report to assess state anxiety (transient emotional condition) and trait anxiety (relatively stable anxious propensity).

BIS-11 (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale) .65 This assesses Cognitive and Motor Impulsivity and Unplanned Impulsivity, as well as a Total Score.

FAST (Functioning Assessment Short Test) .66 This scale assesses the functional impairment of patients with a mental disorder in 6 domains: autonomy, work functioning, cognitive functioning, finances, interpersonal relationships, and leisure.

- •

Presence of criteria of psychopathological severity and comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders: SCID-II, K-SADS-PL/SCID-I

SCID-II (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II) .67 This semi-structured interview assesses BPD criteria as an indicator/proxy of BPD severity (in participants under 18, the presence of criteria for at least the past year is considered) .9

K-SADS-PL (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children-Present and Lifetime version) .68,69 This is a semi-structured diagnostic interview for psychiatric diagnoses for children up to 16 years of age; and SCID-I interview (Structured Clinical Interview for DSM)70 from the age of 18.

In the pre-treatment or baseline evaluation, all the measures described were administered.

For the TaySH post-treatment evaluation, the following tests were administered:

ISAS, DERS, PID-5-SF, BPFSC-11, BPS, BPD Checklist, RS, BDI-II, STAI, BIS-11, and FAST.

Statistical analysisThe sample size for repeated measures analysis of variance was determined using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software. The analysis was calculated with one group and two measurements (pre and post-intervention), a power of 0.80, effect size f of 0.25, and α = .05. The results indicated a total sample size of 34 participants. In exploratory studies, with an alpha of 10, the required sample is 27.

Baseline characteristics were compared with Student's t-test for continuous variables or chi-square tests for categorical variables, with Bonferroni correction. Continuous variables with normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, and categorical variables as percentages. Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. Effect sizes of the comparison were analyzed with Cohen's d. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v26) was used to analyze data. All statistical tests were conducted two-tailed, with an alpha significance level set at p < 0.05.

ResultsSociodemographic dataThe total sample of this study was 37 participants (mean age 16.70 years, SD= 2.42; range 14–23 years), 91.9% of whom were women (n = 34). All participants were single, with a mean number of couple relationships of 1.36 (SD = 1.51). Concerning education, 81.1% of the total sample (n = 30) were studying, and the most prevalent level of education attained was secondary school (59.5%, n = 22). The most frequent comorbidities of other psychiatric disorders were Depressive and Anxiety Disorders (40.54% and 13.51%, respectively), as well as Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, with the combined and inattentive subtypes being the most frequent (29.7% and 18.9%, respectively). Concerning toxic substances, most of the participants did not report consumption at present (73%, n = 27). In 43.2% of the cases (n = 16), the participants received antidepressant pharmacological treatment.

Clinical dataNSSI and psychopathological severity in the total sample at the pre-treatment assessmentThe total initial sample of 37 patients received the primary diagnosis of NSSI. The mean age at the onset of self-injurious symptoms was 13.41 years (SD = 1.83, range 10–18 years), and the first contact with Mental Health facilities was almost one year after the onset of the self-injurious clinical features (M = 14.35, SD = 1.81). More than half of the sample had an associated suicide attempt (67.7%, n = 25), with an average of 1.46 attempts (SD = 1.66). The number of previous psychiatric admissions was 0.36 (SD= 0.59). The severity criterion was established based on the mean number of BPD criteria in the SCID-II interview, which was 4.46 (SD = 1.64).

In relation to the NSSI, patients reported in the ISAS self-report that the main form of self-harm was cutting (54.1%, n = 20), qualitatively describing NSSI as a behavior that mainly produces physical pain (56.8%, n = 21), performed in 78.4% of cases alone (n = 29), and with a reaction time of less than 1 hour between feeling emotional discomfort and self-harm (70.3%, n = 26). Although most wanted to stop self-harming, 21.6% of the cases did not express this desire (n = 8). The quantitative results of the ISAS indicated that the main functions of NSSI were emotional regulation and self-punishment (5.56±0.69 and 4.47±1.54).

The results in the SR suicide risk scale indicated a mean score of 9.92 (SD = 2.46).

Concerning the Emotional Regulation of the DERS, the patients presented high scores in difficulty in managing emotions, especially in the scales of Emotional Lack of Control (understood as a feeling of loss of emotional control, therefore low in emotional regulation) (34.86±6.88), and Emotional Rejection (non-acceptance of negative emotions, and therefore, low in acceptance) (22.89 ± 7.97).

The results obtained in the PID-5-SF indicated that at the dimensional level of personality, patients were characterized by a greater presence of the trait of Negative Affectivity (1.90±0.36), followed by Disinhibition (1.68±0.47). These data seemed to be confirmed by the BPFSC-11 self-report, in which patients obtained high scores in emotional instability as a basic trait (39.84±6.16). Likewise, the scores of the specific scales of Affective Instability and Maladaptive Regulation Strategies of the BPS self-report were higher (12.19±1.91 and 11.11±2.17, respectively). In the BPD Checklist, the total score obtained was 132.28 (SD= 29.69), an indicator for inclusion in psychotherapeutic treatment.

A high total score was obtained in the presence of traumatic childhood experiences in the CTQ (55.22±17.53), the most notable being emotional abuse and emotional neglect (15.76±5.98 and 14.92±4.62, respectively). The scores of 37.76 (SD= 10.15) in the BDI-II, as well as 80.30 (SD = 21.14) in the STAI State and 93.86 (SD = 8.83) in the STAI Trait indicated the presence of significant depressive and anxious symptoms in the total sample studied, as well as the total impulsiveness measured by the BIS-11 (64.92±17.81). A score of 24.54 (SD = 9.54) in the FAST indicated general functional impairment.

Comparison between completer group versus dropout group of the TaySH programOf the total initial sample analyzed, 28 participants (75.7%) completed the TaySH Program (Completer Group or Experimental Group). In the nine participants who dropped out (Dropout Group) (24.3% of the total sample), the main reasons for dropout were: admission to a day hospital or more intensive facilities due to increased severity (n = 4) and academic/work reorientation or improvement and discharge from the program (n = 5).

The two groups of patients were compared. The results of the pre-treatment evaluation between the two are presented in the Supplementary Table. In general, no significant inter-group differences were observed in the sociodemographic data, psychopathological severity, or psychometric outcomes. In non-randomized studies, researchers often face issues such as confounding variables, selection bias, and non-compliance, which can complicate the interpretation of treatment effects. However, in our results after the Bonferroni correction, there were no significant group differences, so the analyses did not covariates for any variable. For more information on the total sample, please refer to the Supplementary Table.

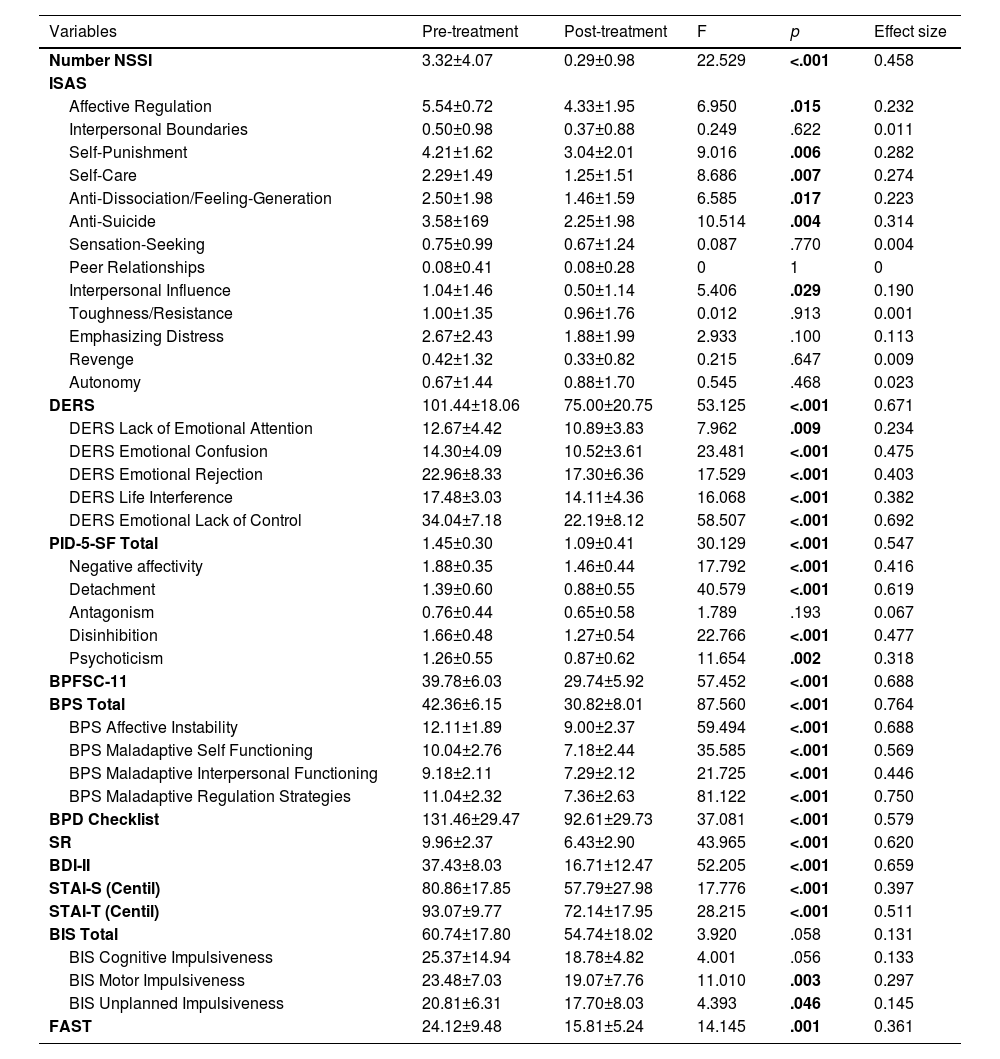

TaySH programApplication of the TaySH program and study of its effectiveness at post-treatmentUpon completion of the TaySH Program, all patients of the Experimental or Completer Group underwent a post-treatment evaluation. The results that allow comparing its pre- and post-treatment effectiveness are presented in Table 1.

Pre-Post TaySH with Repeated measures ANOVA (n = 28).

Number NSSI: Number of NSSIs during the week collected in the TaSH Program; ISAS: Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury; DERS: Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; PID-5-SF: Personality Inventory for DSM-5- Short Form; BPFSC-11: Borderline Personality Features Scale for Children; BPS: ICD-11 Borderline Pattern Scale; BPD Checklist: Borderline Personality Disorder Checklist; SR: Suicide Risk; BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; BIS-11: Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; FAST: Functioning Assessment Short Test.

Concerning the number and frequency of NSSI, the main outcome of this study, indicate that the TaySH Programa produced a statistically significant decrease in the number of weekly NSSIs, going from a pre-treatment mean of 3.32 (SD = 4.07) to a post-treatment mean of 0.29 (SD = 0.98, p < 0.001), with an effect size of 0.458, moderately close to a medium effect size (See Fig. 1).

Likewise, the results of the functionality of NSSI behaviors according to the ISAS self-report indicate a statistically significant improvement; that is, patients stopped considering and understanding NSSI as a means to achieve affective regulation and self-punishment, as well as self-care, as a way to anti-dissociation/ feelings generation of anti-suicide through NSSI (p = 0.015, 0.006, 0.007, 0.017, and 0.004, respectively). The effect sizes of the ISAS were between 0.190 and 0.314, which are considered small. Suicide risk decreased statistically and significantly at the total post-score of 6.43±2.90 (p < 0.001, with a moderate effect size of 0.620), according to the SR scale (see Table 1).

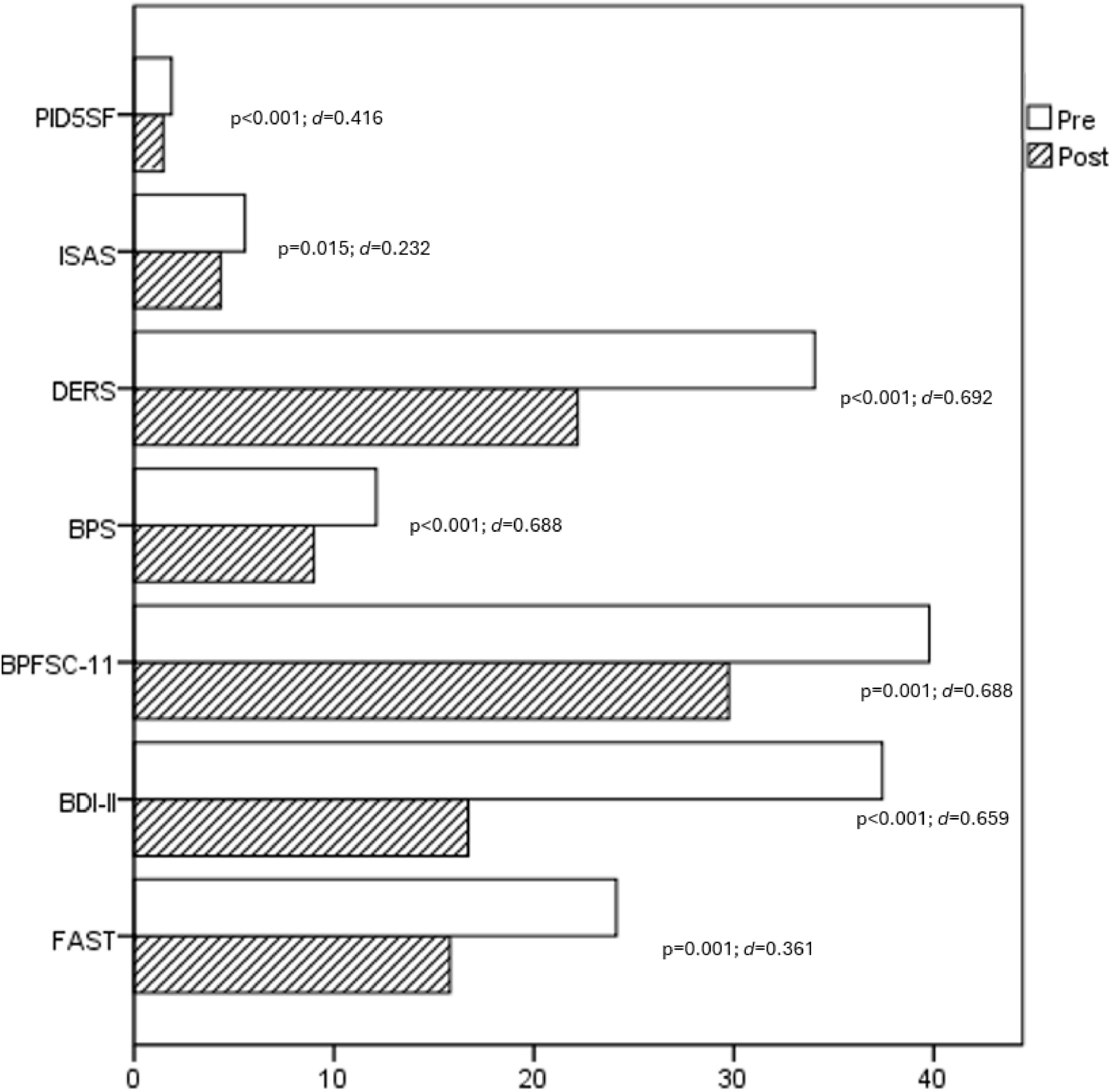

The results obtained in the clinical picture of emotional dysregulation associated with NSSI showed statistically significant differences in all the pre-post tests administered. After implementing the TaySH Program, the post DERS showed a significant decrease in all the scales, and a mean total score of 75.00 (SD = 20.75, p < 0.001), and a moderate effect size (d = 0.671). The same was observed in the results of the post PID-5-SF, with a statistically significant decrease in the total score (1.09±0.41, p < 0.001, d = 0.547), and in 4 of the 5 personality dimensions (except for Antagonism; p = 0.193). Concerning the total BPFSC-11, the patients who completed the program showed a significant decrease of almost 10 points in the total score, reaching 29.74 (SD = 5.92, p < 0.001), with a moderate effect size (d = 0.688). When post-treatment BPS was analyzed, the results indicated a significant improvement in both the total score and all of its specific scales of Affective Instability, Maladaptive Self Functioning, Maladaptive Interpersonal Functioning, and Maladaptive Regulation Strategies (p < 0.001), with moderate effect sizes. Concerning the post-treatment BPD Checklist, the results obtained showed significant differences in the total pre score (pre: 131.46±29.47 versus post: 92.61±29.73, p < 0.001, d = 0.579).

The post-treatment results also suggested a statistically significant decrease in depressive and anxious symptoms, and in motor and unplanned impulsiveness associated with NSSI after the TaySH program, reflected in the BDI-II, STAI, and BIS-11 self-reports (p < 0.001 in the first two, and p = 0.003 and p = 0.046 in the last two) (See Table 1).

A significant improvement was also observed in functionality in the FAST, obtaining a mean of 15.81 (SD= 5.24, p = 0.001), statistically lower than the pre-treatment baseline score. Fig. 2 shows the impact of the intervention on emotional regulation and functioning.

Comparison of emotional dysregulation and impact on functionality after the TaySH intervention (pre-post).

Although NSSI behaviors are a serious public health problem for children and adolescents, the development of evidence-based psychotherapeutic treatments specifically designed for their management in young people and the study of their effectiveness remain very scarce.

This pilot study presents a new program, the TaySH Program, whose main objective is to analyze its effectiveness in the reduction of NSSI and in the associated psychopathological clinical picture after its application to an outpatient clinical sample of young people in the TAY stage based on a pre-post-treatment analysis. Our results suggest that it is effective in obtaining a significant reduction of NSSI as its primary outcome, as well as in the associated psychopathological clinical picture, especially in suicide risk, emotional dysregulation, depression, anxiety, and impulsiveness as secondary outcomes, thus improving the patients' psychosocial functioning. The moderate effect sizes observed in the reduction of suicide risk (d = 0.620), emotional dysregulation (d = 0.671), and impulsiveness (d = 0.547) further underscore the importance of these changes, emphasizing that the interventions have a moderate practical impact on patients' lives. In contrast, the smaller effect sizes found for the ISAS outcomes (ranging between 0.190 and 0.314) highlight that, while the changes are statistically significant, they may reflect more subtle shifts in patients' understanding and use of NSSI for affect regulation and self-care. Although these are preliminary results of the TaySH, the findings of this pilot study have several important clinical implications. The data presented coincide in underlining the importance and need for early, structured, and intensive psychotherapeutic interventions focused on repetitive NSSIs to achieve a significant improvement in patients’ clinical manifestations and psychosocial functioning.23,33,45,71,72 The significant reduction in NSSI behaviors observed suggests that the TaySH Program could serve as a first-line intervention for adolescents and young adults in the TAY stage, highlighting the need for early intervention to mitigate long-term risks associated with NSSI.

Different elements of the TaySH Program could contribute to this significant overall improvement. First, it seems that, on the one hand, its short format of 12 sessions and its frequency of individual weekly sessions likely facilitates a focused and intensive therapeutic process, contributing to a rapid reduction of NSSI. This structure allows for regular monitoring and support, which may help maintain the patient's engagement and adherence to the program. On the other hand, the use of psychotherapeutic elements such as psychoeducation, motivation, and active participation, contribute to a rapid reduction of NSSI. Specifically, the literature has pointed to motivation as one of the main variables to be considered a possible moderating factor in the efficacy of treatment for young people, and it is partly responsible for the increase or decrease in psychopathological behaviors.45,71 Moreover, training in strategies for the use of functional alternative behaviors based on self-responsibility and the psychoeducation of the family seem to contribute to the greater effectiveness of the TaySH Program. These results are consistent with the study by Boege, Schubert, Scheider, and Fegert45 in their “Cut the Cut” program, in which they indicate that patients report that specific interventions in these behaviors are very useful for self-management, self-care, and the use of alternative skills, which are associated with a faster reduction of NSSI, especially during the first interval of the program. Finally, the holistic approach of the TaySH Program, which addresses both the symptomatic and contextual aspects of NSSI behaviors, likely plays a crucial role in its effectiveness. By combining individualized therapy with family involvement and specific skills training, the program may foster a comprehensive change process that helps patients to reframe their understanding of NSSI and to develop healthier coping strategies.

Also, unlike the few existing programs, one of the novelties of the TaySH is that it intervenes in a target population that falls within a broader evolutionary period that includes ages 12–13 to 25 years. Thus, we agree with the literature in pointing out that it is a fundamental period of neurodevelopment and, consequently, of high vulnerability for the development and manifestation of most mental health problems or psychopathological disorders.19 Therefore, we should cease to approach from a more traditional and even arbitrary approach, but instead, approach it from a broad evolutionary perspective, considering that these behaviors, like most psychopathological disorders, occur in this critical stage of transition from childhood to adulthood. Intervening in this phase is essential to prevent the consolidation of negative behavior patterns and promote healthy development.

On the other hand, at the clinical level, our results support the idea that specialized psychotherapeutic intervention as a first line of treatment is effective for the management of the psychopathological difficulties of emotional dysregulation, psychopathological clinical manifestations, and associated psychosocial functioning in adolescents and young people with NSSI. Our results show a significant decrease in post-treatment NSSI, and, consequently, a decrease in suicide risk in the short term. In this sense, our results coincide with studies such as that of Koening et al. ,32 which indicate that, although repeated NSSI in adolescents and young adults has been identified as a predictor of suicidal behaviors, in those who cease self-harming, the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors one year after having stopped is comparable to the risk of those who have never self-harmed. These results are particularly interesting and encourage future studies to analyze whether these changes are maintained, as indicated in the literature. After receiving the treatment, our patients obtained results that support the claim that TaySH has achieved a substantial and significant improvement in the different clinical areas studied, with a significant decrease in the baseline and greater emotional well-being. Although adolescence is defined as a period characterized by emotional instability, significantly high scores prior to the start of treatment are indicative of a psychopathological clinical condition that affects the quality of life. Although these results coincide with those obtained in previous studies such as that of Schmeck et al.73 with BPD adolescents, future studies should determine whether the changes in our program are sustained over time, thus avoiding the evolution towards more complex psychopathological conditions.

Thus, our data confirm the results of some studies about the basic clinical decision of a highly specialized treatment for NSSI based on the evaluation of potential benefits and risks, including addressing autolytic risk, psychopathological severity, attention to the medical needs of the comorbidities, as well as difficulties in carrying out daily routines, especially regarding schooling.71,74 Only in this way can an improvement in the clinical manifestations and prognosis of these patients be achieved, slowing down a possible evolution towards more complex psychopathological forms. This is also considered one of the most cost-effective options. However, the reality is that most of the adolescents with NSSI, unfortunately, do not receive adequate treatment for different reasons. We highlight their low tendency to seek help, and that some clinicians consider this type of behavior a professional challenge due in part to their limited training, and a current reality in which psychotherapeutic options are still scarce and, therefore, with limited published results.23 However, the data from our program are of interest as they may contribute to improving this situation. All these results, although preliminary, support the idea that the TaySH Program could be considered a beneficial option as a first intervention for adolescents and young people who present NSSI, due to its brevity, accessibility, and specificity for its use in different communitarian and specialized child and adolescent mental health facilities. Structuring psychotherapeutic interventions according to a model based on the stepped-care-treatment approach of clinical routine could be a more effective way of offering tailored treatment to patients in routine clinical practice. Placing the TaySH Program as part of this model, as suggested by some authors, it should be considered a first gateway to an intervention that, in addition to being economical, could reduce the barriers and stigma that prevent many adolescents and young people who start to commit NSSI from seeking help for early treatment. It would allow them to receive early and appropriate psychotherapeutic care according to their level of psychopathological affectation, before a torpid evolution towards more complex forms.23 Therefore, our program can be considered an interesting option due to its brevity and economy and the reduced waiting time that it can mean for patients who require treatments for these behaviors.

Although the results obtained are significant, they should be interpreted cautiously due to some of the study's limitations. Firstly, this is a pilot study that has not been randomized. Nonetheless, it provides valuable preliminary data that can guide larger, methodologically rigorous future studies. Secondly, the size of the sample studied is a limitation. However, we point out that studies on psychotherapeutic interventions usually involve small samples, and our study presents an interesting sample. Finally, a limitation is related to the sex distribution, as the sample was predominantly female. However, it is consistent with most of the studies that show a higher number of women with NSSI than men. This imbalance has also prevented subgroup analyses due to the limited sample size, thereby constraining the ability to assess differential treatment responses, such as variations in response by sex. Despite these limitations, the results obtained are encouraging, and further studies on its effectiveness in clinical trials and in different settings are recommended to confirm the results. We also recommend longitudinal studies to determine whether the changes obtained remain stable and to confirm the results presented in more heterogeneous patient samples.

ConclusionThe results of the present study provide preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of the TaySH Program as the treatment of choice in individual format for the reduction and management of NSSI, as well as the underlying psychopathological symptoms in adolescents and young adults who present this type of problem behavior. The rapid detection of risk behaviors in young people in the transition stage from childhood to adulthood through exhaustive diagnoses and the comprehensive approach with specific strategies based on scientific evidence, performed in an outpatient context that preserves their academic, social, and family adaptability as much as possible, are some of the highlights of the program. The significant results obtained at post-treatment support its effectiveness as a recommended approach for these cases. While this pilot study lays the groundwork for further research on the TaySH Program, the promising findings highlight the need for randomized controlled trials to validate its efficacy and to assess the long-term maintenance of treatment gains.

Ethical approval and consent to participateThis study is part of a project approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron of Barcelona, Spain (PR (AG) 312/2023). This study was not preregistered. All the admitted patients and their parents were invited to participate in the study. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all parents and participants before study participation.

Declaration of transparencyThe corresponding author declares that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent report of the present study, that no relevant aspect of the study has been omitted, and that the differences from the pre-planned study have been explained (and registered, if relevant).

Authors’ contributionsN.C. designed the study. N.C., M.F., M.O., and C.P. participated in the recruitment of participants, and applied the Program TaySH. S.A. and J.L.M. analyzed the data. N.C., M.F., S.A., and J.A.R.Q.M. interpreted the data, reviewed the scientific literature, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the preparation of the final manuscript and have approved it.

Availability of data and materialsThe data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. SA has been a consultant and/or has received fees/grants from Otsuka-Lundbeck, without any financial or other relationship relevant to the subject of this article.

Financial support was provided by public funds from the Department of Mental Health and Addictions (Government of Catalonia, Health Department). SA thanks the Fundació La Marató de TV3 (202206-30-31) for its the support.