This study explored the correlation between nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and family functioning among adolescents aged 12 to 17 years with mood disorders.

MethodsA total of 142 participants were clinically assessed for NSSI, with 85 in the NSSI group and 57 in the non-NSSI group. The correlation between NSSI and family functioning was compared and a regression prediction model was constructed to determine the risk probability of NSSI.

ResultsA significant association was found between family functioning and NSSI (P = 0.017). The correlation between adolescents with NSSI and gender, communication, affective responsiveness, and behaviour control was statistically significant. A nomogram graph and ROC curve were constructed, with an AUC of 0.772.

ConclusionThe findings support the notion that family functioning is associated with a higher risk for NSSI among adolescents with mood disorders. Furthermore, gender, communication, affective responsiveness, and behaviour control may be contributing factors.

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a prevalent manifestation of mental health issues in adolescents and is commonly employed as a coping mechanism to deal with personal negative emotions that appear insurmountable.1 Particularly in adolescence, when cognitive functions are still developing, adolescents may resort to self-injury to manage overwhelming emotions that they cannot adequately process or comprehend.2 According to the DSM-5, NSSI without suicidal intent refers to a deliberate act of self-injury that is not socially sanctioned.3 Common forms of NSSI among adolescents include cutting, scratching, hitting, and scraping.4 When NSSI occurs in areas other than the arms, such as the wrist, it poses a serious risk of suicidal behaviour.5 Thus, understanding the phenomenon of NSSI in adolescents is of utmost importance, as it has implications for their mental health and well-being.

NSSI is a prevalent behaviour among adolescents in both community and clinical settings, with lifetime prevalence rates ranging from 17% to 60%.6 Studies have shown that 14% to 15% of adolescents in the community sample and over 40% of those in the psychotic sample have exhibited NSSI behaviours.7 NSSI peaks during mid-puberty (approximately 15–16 years) and starts to decline during late puberty (approximately 18 years).8,9 Adolescents with NSSI frequently receive diagnoses of mood and other psychiatric disorders,10 with 37% to 52% of patients with depressive or bipolar disorders having engaged in NSSI at least once.11,12 Family factors such as early or prolonged separation from parents, emotional neglect, and psychological or physical abuse have been identified as significant triggers for NSSI.13 It is crucial to explore and understand the various factors in family functioning that contribute to NSSI among adolescents and develop effective interventions for prevention and treatment.

Family functional factors play imperative roles in NSSI in adolescents. We generally consider that high-quality family function has a protective effect on NSSI.14 Family support is necessary to ensure the healthy mental development of adolescents.15 Adolescent individuals are in a period of emotional change, often manifested as impulsive behaviour, and with the influence of insufficient family support and great stressful events in daily life, they may use incorrect methods to resolve their negative emotions.2 There is a clear correspondence between family and recurrent NSSI, and severe NSSI in adolescents.15 The family support system is vital in the occurrence, development, and termination of NSSI,16 effectively helping them to learn coping skills and reduce the impact of negative emotions.

One longitudinal study17 of 6 years showed that although the surveyed research affords unsatisfactory substantiation for a direct causal association between family function and NSSI, it raised questions about the specificity of implicated risk factors, and the nature and function of protective factors in families. This suggests that there is still much need to explore these elements further. Michelson suggests that the occurrence of NSSI behaviour may be positively associated with family conflict and that positive parent‒child communication and feelings of understanding by loved ones are protective factors.17 Protective factors, such as good communication and sufficient respect and recognition in the family, can help them to effectively deal with negative events, be expressively less impulsive, and perform less NSSI. Hazardous factors, for instance, childhood family adversity, may lead to long-term psychologically adverse pathological outcomes. The current findings suggest that early intervention in childhood family adversity may reduce the possibility of NSSI behaviour by improving family function.18

At present, there is still no consistent conclusion about the relationship between family function and adolescent NSSI especially in adolescents with a high incidence of NSSI with mood disorders,19 and the relationship between the two still needs further research. This study aims to explore the relationship between family functioning and NSSI in Chinese adolescents with mood disorders. By identifying the specific family factors that contribute to NSSI and developing effective intervention strategies to improve family functioning, this study will help to reduce the incidence of NSSI and improve the mental health outcomes of Chinese adolescents with mood disorders.

MethodsParticipantsA total of 142 adolescents with mood disorders aged 12–17 who visiting our hospital from October 2019 to October 2021 were selected as the research subjects, and the participants were diagnosed with unipolar and bipolar depression through clinical consultation by two well-trained clinical psychiatrists according to the recommended diagnostic criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), selected the participants suffer only from unipolar depression or bipolar depression and divided into an NSSI group and non-NSSI group according to the recommended NSSI diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5.20 Before the investigation, all participants and their guardians were informed of the purposes and procedures of the study in detail.

MaterialsThe Family Assessment Device(FAD) is compiled according to The McMaster Model of Family Functioning(MMFF), which can simply and efficiently find possible problems in the subject's home and collect information on all aspects of the entire family system.21 It is divided into seven subscales (1.Problem-Solving, PS: 6 items; 2.Communication, CM: 9 items; 3.Roles, RL: 11 items; 4.Affective Responsiveness, AR: 6 items; 5.Affective Involvement, AI: 7 items; 6.Behaviour Control, BC: 9 items; 7.General Functioning, GF: 12 items). Higher scores indicate worse related home features. The reliability and validity of its measurement assessment have been demonstrated.22

This study uses Shek's the Chinese version of the Family Assessment Device,23 which published in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (ed AC Michalos) in 2014, they verified the Chinese version of the Family Functioning Scale has good reliability and validity. And Cronbach's α of our sample is 0.91. Self-administered questionnaires were used to collect participants’ sociodemographic characteristics and psychological characteristics. The 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD-24) was utilized to assess the severity of unipolar and bipolar depression.

Statistical analysesAnalysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables were utilized to compare differences in the characteristics of the two groups (participants with and without NSSI).

Logistic regression fitting was performed with NSSI as the dependent variable and sex, FAD total score, and each subfactor as the independent variables. The binary logistic regression analysis model was included, and the Enter method was used for statistical analysis. Whether the model was ideal for interpreting the original data was judged by testing the fitting of the model through the Hosmer and Lemeshow test.

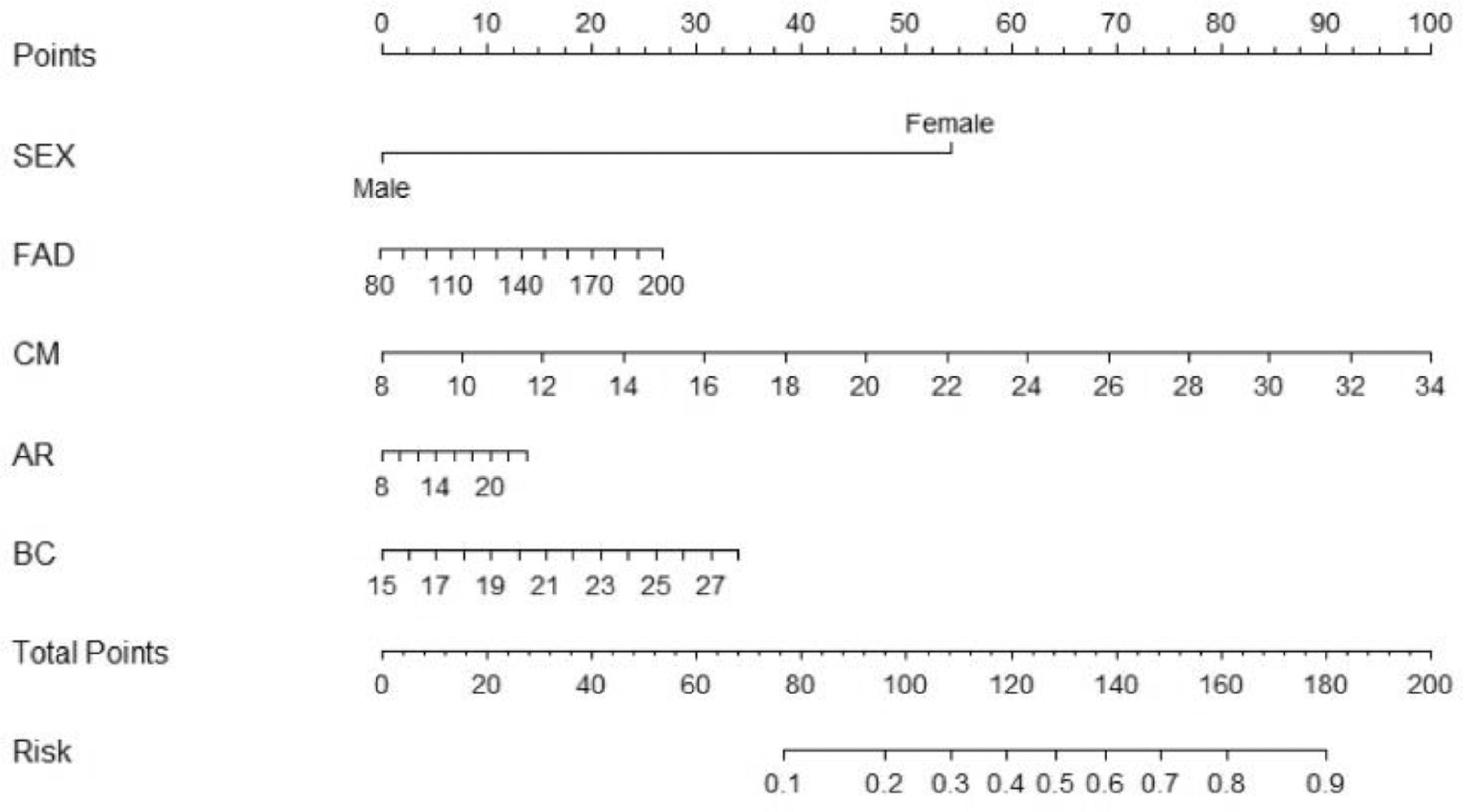

A nomogram graph, which is based on the degree of influence of each independent variable on the dependent variable in the multifactor logistic regression prediction model, was constructed, and a regression coefficient, which assigns points to the value of each variable to calculate the predicted value of individual outcome events was used.24

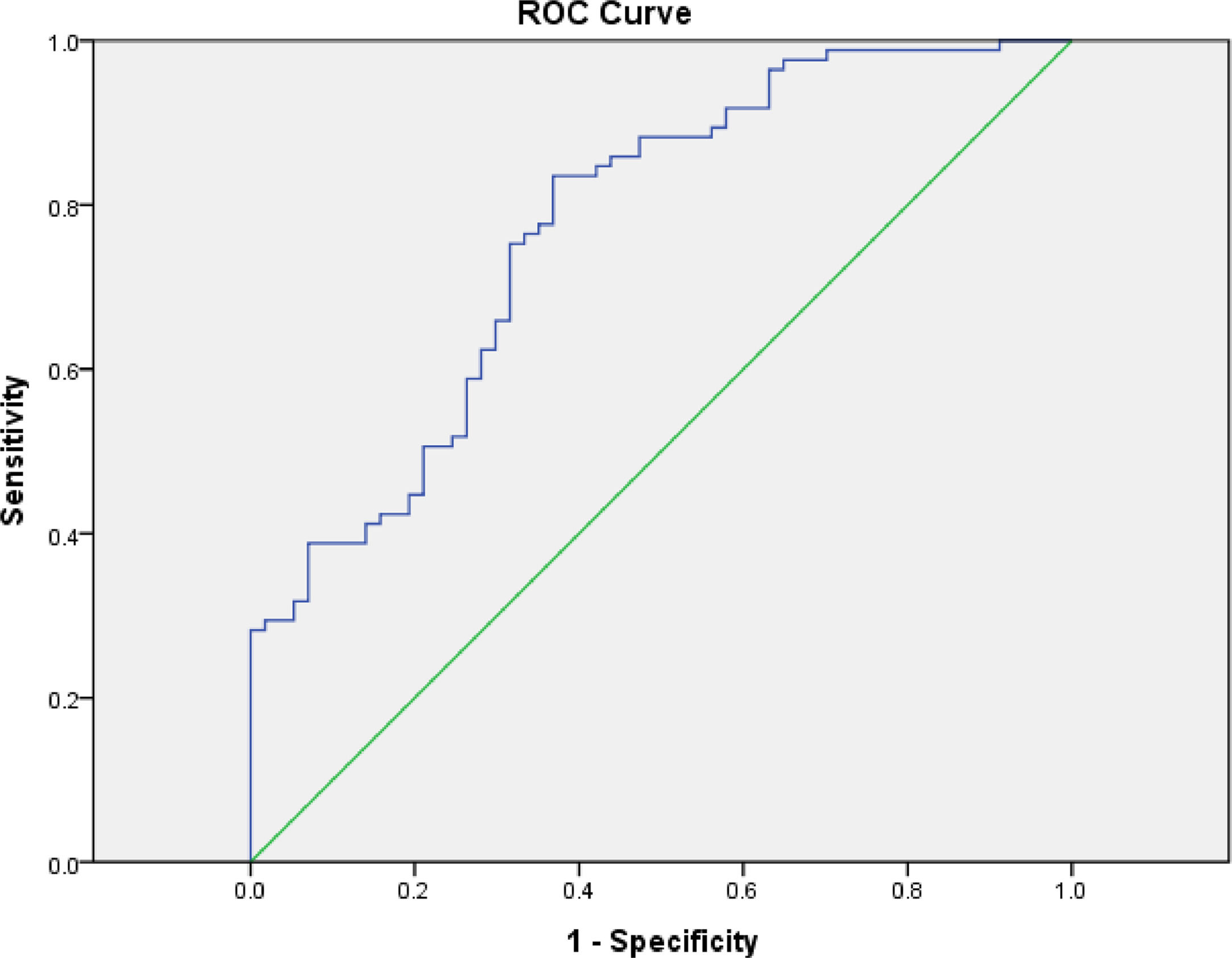

By constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and calculating the area under the curve, AUC, the sensitivity, specificity, and maximum Youden index of the logistic regression prediction model was evaluated. An AUC between 0.5–1 indicates that the predictive model is meaningful.

The data were analysed with SPSS 18 software and The R Project for statistical computing and graphics. All tests were performed by bilateral tests, and the results of this study were statistically significant at P<0.05.

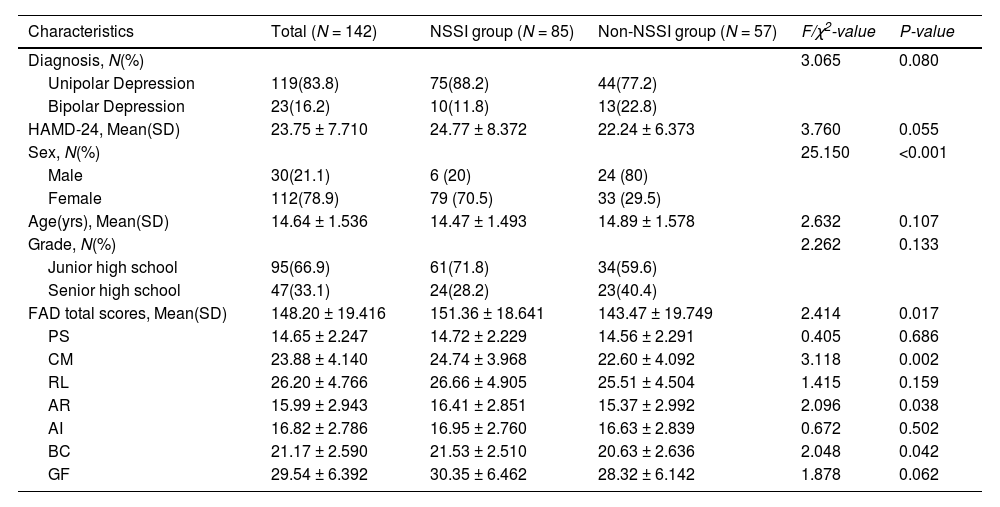

ResultsGeneral dataAccording to the grouping criteria, 142 Chinese adolescents with mood disorders were enrolled in the research group, and 85 (59.9%) were divided into the NSSI group and 57 (40.1%) into the non-NSSI group. Of these, 30 (21.1%) were boys, and 112 (78.9%) were girls. Of these 142 adolescents, 119 were diagnosed with unipolar depression (75 in the NSSI group, 44 in the non-NSSI group), and 23 were diagnosed with bipolar depression(10 in the NSSI group, 13 in the non-NSSI group). Of these teenagers, 95 were in junior high school(61 in the NSSI group, 34 in the non-NSSI group) and 47 in senior high school (24 in the NSSI group, 23 in the non-NSSI group).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants with and without NSSI. More women than men participated in this study. There were no significant differences in diagnosis, HAMD-24 scores, age, or grade between the two groups (all P> 0.05), and there were significant differences in sex (χ2 = 25.150, P<0.001).

Demographic and psychological characteristics of participants with and without NSSI.

HAMD-24, Hamilton rating scale for depression-24; FAD, family assessment device; PS, problem solving; CM, communication; RL, roles; AR, affective responsiveness; AI, affective involvement; BC, behaviour control; GF, general functioning.

As shown in Table 1, after statistical analysis, the Family Functioning subfactors in the NSSI group scored higher than those in the non-NSSI group, indicating that adolescents with mood disorders in the NSSI group had worse family functions. Among the variables, there were significant differences between FAD total scores (P = 0.017), CM (P = 0.002), AR (P = 0.038), and BC (P = 0.042).

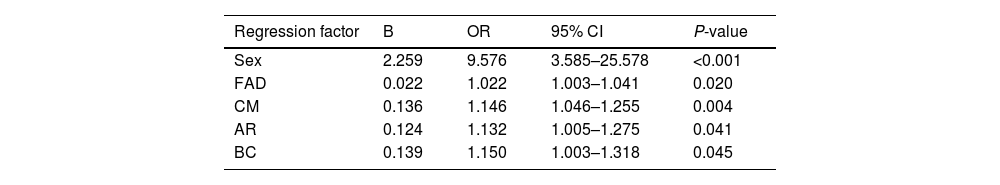

Logistic regression analysisWith NSSI as the dependent variable, characteristics (sex, FAD, CM, AR, and BC) that were statistically significant (P<0.05) by validation were selected as independent variables for binary logistic regression (see Table 1). The model has a high fitting degree, and the interpretation of the original data is ideal. The results showed that SEX (OR=9.576, P<0.001), FAD total score (OR=1.022, P = 0.020), CM (OR=1.146, P = 0.004), AR (OR=1.132, P = 0.041), and BC (OR=1.150, P = 0.045) were significant in the analysis. On the basis that other variables remained unchanged, with SEX as a risk factor, the probability of adolescents developing NSSI behaviour increased by 857.6% (OR-1 = 8.576) . With the FAD total score as a risk factor, the probability of adolescents developing NSSI behaviour increased by 2.2% (OR-1 = 0.022). With CM, compared with other samples, the probability of adolescents developing NSSI behaviour increased by 14.6% (OR-1 = 0.146). With AR, the probability of adolescents developing NSSI behaviour increased by 13.2% (OR-1 = 0.132) relative to other samples. The probability of NSSI behaviour in adolescents was increased by 15% (OR-1 = 0.150) compared with other samples in BC (see Table 2).

Logistic regression analysis of NSSI and Non-NSSI groups and impact factors.

FAD, family function total scores; CM, communication; AR, affective responsiveness; BC, behaviour control.

Through stepwise regression, with NSSI as the dependent variable and the subfactors that are statistically significant mentioned in Table 1 as the independent variable, multifactor logistic regression was included to construct a nomogram graph of the logistic regression prediction model to predict the risk of NSSI (see Fig. 1). A nomogram model was developed to predict the risk of NSSI based on the previous significant factors in the binary logistic regression analyses, including SEX, FAD, CM, AR, and BC. In the prediction model, the corresponding scores of the above variables were added to the nomogram model to obtain the total points, which was ultimately converted to the probability of adolescents developing NSSI (from 0 to 100%).

Evaluation of the logistic regression prediction modelAccording to the ROC graph of the logistic regression prediction model, AUC=0.772, P<0.001, and 95% CI=(0.694, 0.851). According to the calculation of sensitivity and specificity, the maximum Youden index = 0.467, the optimal cut-off point = 0.597, the sensitivity = 0.835, and the specificity = 0.368 (see Fig. 2).

A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of NSSI behavior of Chinese adolescents with mood disorders based on family functioning. It connects coordinate points with 1 - specificity (= false positive rate) as the x-axis and sensitivity as the y-axis at all cut-off values measured from the test results.

Currently, NSSI remains prevalent among adolescents in various countries and is recognized as a significant public health concern affecting their physical and mental well-being.25 Of particular note is the increasing trend of NSSI among adolescents since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic worldwide.26 This alarming trend has garnered the attention of scholars nationally and internationally. The central aim of the present study was to investigate the potential link between family functioning and the history of NSSI among patients diagnosed with mood disorders. Our findings suggest that, in 142 participants (30 males and 112 females), there was a significant correlation between gender and NSSI, with the incidence of NSSI in female adolescents being higher than that in male adolescents. Moreover, our analysis indicates that specific dimensions of family functioning, including communication, affective response, and behavioural control, may contribute to the onset of NSSI in this population, thus advancing the current understanding of this complex phenomenon in the literature.

This study showed that adolescents who engage in NSSI generally have worse family functioning, as indicated by higher FAD total scores than non-NSSI adolescents. This highlights the importance of family functioning in preventing NSSI. Early life experiences within the family, are known to play a critical role in shaping adolescent character and behaviour.27 The family plays an essential role in the occurrence, development, and cessation of NSSI behaviour.18

After conducting our analysis, we found that female adolescents are more likely to develop NSSI and that there is no obvious correlation between age and NSSI which differs from previous studies that have examined the relationship between age and NSSI. For example, Plener et al.8 found that the NSSI rate peaks at age 15, while other longitudinal studies have shown a decline in NSSI from adolescence to adulthood.28,29 We believe that the discrepancies between our findings and those of previous studies may be due to the limitations in the quantity and distribution of participants involved in our study. Additionally, some potential patients with NSSI may not have sought psychological intervention promptly, which could have biased our results against previous studies on NSSI and age. When examining the literature on the relationship between gender and NSSI, we found that different studies have shown different conclusions. The results of a meta-analysis show that females are at a higher risk of engaging in NSSI than males. However, epidemiological studies suggest that the effect size may be small.30 Other research has shown that the gender difference in NSSI is not static, with the gap widening in mid-adolescence and gradually disappearing by early adulthood.31 We believe that the reason females are at a higher risk of developing NSSI than males may be due to the diversity of biological factors, such as differences in hormones such as testosterone and oestradiol, which may influence gendered engagement in NSSI.32 Other factors may also play a role in gender-related NSSI, such as the socialization of emotions. Previous research has shown that women report engaging in emotion regulation strategies more often than men and that their ways of dealing with emotions may increase the risk of NSSI, for example, when women engage in rumination.32–34

Our results revealed that adolescents in the NSSI group scored significantly higher on the Communication subscale than those in the non-NSSI group. This finding supports previous research that indicates that poor family communication is associated with adolescent self-injury.35 A meta-analysis of 92 studies further suggests that negative interactions between parents contribute significantly to children's problems.36 In China's rapidly developing society, the prevalence of NSSI among adolescents is on the rise due to the lack of communication with parents resulting from their absence in large cities for work.37 Improving parent-adolescent communication is essential for reducing the incidence of mental health problems in adolescents.38 Hilt & Prinstein et al. 39 reported that poor communication with fathers increases the risk of NSSI in intact families. This highlights the importance of studying the relationship between every family member and adolescents explicitly to further understand the association between family functioning and NSSI. In the era of the internet, adolescents often seek emotional catharsis online when there is not good communication within the family. Brown's 40 analysis showed that pictures and written communication about NSSI are prevalent online. Adolescents search for others who share similar experiences to find comfort, but this can lead to more severe NSSI behaviours and the development of "social infection" through collective NSSI behaviours.

We also found that the scores of Affective Responsiveness were significantly higher in the NSSI group, as in Kim's previous study.41 This finding supports a strong correlation between the degree to which adolescents respond emotionally to stimuli and NSSI.42 Adolescents with NSSI showed lower emotional awareness when processing negative emotions, which is generally accepted as a means of eliminating negative emotions and relieving pressure.3,43 The lack of emotional awareness can be attributed to the home environment, particularly the emotional responsiveness of family members. Fruzzetti et al. 44 describe a complex interaction between the emotion regulation problems of a child and the reaction of family members to their behaviour. When the expression of positive emotions of adolescents is ignored by family members, they become negative. The deterioration of family functioning leads to vicious changes in adolescent emotional regulation, which in turn strengthens adolescents' adaptation to undesirable emotional patterns. The construction of corresponding emotional responses with others is crucial for adolescents to adapt to society.45 Adolescents who have poor affective responsiveness due to family dysfunction may encounter problems in their relationships with society in the future.

Our results suggest that family members should keep an eye on their family's behavioural control of adolescents. Adolescents with NSSI face more behavioural control during their parents' upbringing.46 However, inconsistent results have been found regarding parental behavioural control, possibly due to different measures used to assess behavioural control and different definitions.47,48 Parental involvement in changing their parenting and behaviour styles after learning about NSSI in their children has been found to reduce the incidence of NSSI in children.49 Xu Wang 50 found that adjusting parents' negative perceptions and behavioural patterns of NSSI is beneficial in reducing adolescent-parent conflict and preventing NSSI. Adolescents with long experiences of control often have difficulty regulating their emotions, and may be impulsive when encountering difficulties.41,51 NSSI behaviour is considered an inappropriate way to cope with negative emotions.52,53 and often occurs following experiences of anxiety, insecurity, fear, and sadness. In the absence of effective coping strategies, adolescents may resort to self-injury as a means of managing their emotions.

In summary, our investigation revealed that patients diagnosed with mood disorders who engaged in NSSI exhibited poorer family functioning. This discrepancy was particularly evident in areas of communication, affective response, and behavioural control. Notably, female adolescents were more likely to exhibit NSSI behaviour than their male counterparts. We observed a positive correlation between the degree of impaired family function and the likelihood of future NSSI. We anticipate that our findings will hold considerable practical implications for identifying and providing timely interventions for individuals who exhibit NSSI behaviour in the future.

LimitationsSeveral limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the participants were solely recruited from a single hospital, thus the generalizability of findings to adolescents in other regions remains uncertain. Additionally, the age range of participants was limited to 12–17 years old, which may impact the generalizability of results to a wider age range. There were significantly fewer male subjects in the NSSI group, which could limit the explanation of the results for male patients. Second, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, it is not possible to establish a causal relationship between NSSI and family function. Future research should incorporate mediation analysis to investigate the role of mood disorders in this relationship.

ConclusionAlthough current research has shown that family functioning plays a role in nonsuicidal self-injury, communication, affective responsiveness, and behaviour control clearly occupy a more important position. In addition, gender seems to be an important influencing factor for adolescent NSSI behaviour. We hope that this study can make the public aware of the importance of the above three aspects of family functioning, and call on society or the country to take necessary guidance measures for the improvement of adolescent family functioning in the early stages.

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of the Affiliated Hangzhou First People's Hospital of Zhejiang University (IRB: 2020-K008–01, January 2020). The patients or their guardians provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

This work is supported by the Zhejiang Medical Association Program (grant number: 2023KY920). The funder had no role in operation of this project and did not have any involvement in the preparation, review, approval, or decision to submit this manuscript for publication.

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily of the Zhejiang Medical Association. Infrastructure support for the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics was provided by the Department of Clinical Psychology, Affiliated Hangzhou First People's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University.