The WHO's End TB Strategy promotes using rapid molecular assays as initial diagnosis to reduce tuberculosis globally. This prospective study assessed commercial molecular platforms’ effectiveness in diagnosing or ruling out tuberculosis (TB) in a low-prevalence setting.

MethodsOne hundred clinical samples (80 respiratory/20 non-respiratory) were included among all samples routinely received in a mycobacterial laboratory. Five real-time polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assays (Xpert-MTB/Rif-Ultra, BDMAX-MDR-TB, RealTime-MTB, FluoroType-MTBDR, Anyplex-MTB/NTM) were characterized and compared through blinded-parallel analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, and Cohen's Kappa were calculated to assess the accuracy and agreement of RT-PCR results with culture.

ResultsSensitivity ranged 88.89–100%, improving initial screening by 30–40%. Specificity was 96.70–98.98%. RT-PCR showed excellent discriminatory power, as TB patients were 26.9–91.0 times more likely to test positive. Cohen's Kappa showed substantial to excellent concordance (0.78–0.94).

ConclusionRT-PCR improves TB initial diagnosis, offering tailored solutions for diverse laboratories, revolutionizing control strategies with its operational flexibility.

La Estrategia Fin a la Tuberculosis (TB) de la OMS impulsa ensayos moleculares rápidos como diagnóstico inicial de tuberculosis. Este estudio evaluó su eficacia en un entorno de baja prevalencia.

MétodosSe incluyeron cien muestras clínicas (80 respiratorias/20 no respiratorias) recibidas rutinariamente en el laboratorio, analizando en paralelo 5 ensayos moleculares comerciales de RT-PCR (Xpert®-MTB/Rif-Ultra, BDMAX™-MDR-TB, RealTime-MTB, FluoroType®-MTBDR, Anyplex™-MTB/NTM). Se calcularon sensibilidad, especificidad, razones de verosimilitud y el índice kappa de Cohen para evaluar la precisión y la concordancia de los resultados de RT-PCR con el cultivo.

ResultadosLa sensibilidad fue entre el 88,89-100%, mejorando el cribado inicial un 30-40%. La especificidad fue entre el 96,70-98,98%. Las RT-PCR mostraron un excelente poder discriminatorio, ya que los pacientes con tuberculosis eran 26,9-91,0 veces más propensos a dar positivo. El índice kappa Cohen mostró una concordancia de sustancial a excelente (0,78-0,94).

ConclusiónLas RT-PCR mejoran el diagnóstico inicial, ofreciendo soluciones adaptadas para diversos laboratorios, y revolucionando las estrategias de control con su flexibilidad operativa.

Microbiological diagnosis plays a fundamental role in the control of tuberculosis (TB). Globally, out of the 5.3million people diagnosed with pulmonary TB in 2021, only 63% were confirmed microbiologically,1 highlighting the urgent need to equip microbiology laboratories with all techniques that provide a rapid and accurate diagnosis.

The microscopic examination, or acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear microscopy is the most common initial diagnostic test, used for the identification of the most contagious patients and the quantification of the bacillary load. Pretreatment of the sample by centrifugation, as well as the use of fluorescence staining, increases the sensitivity 10%.2 Mycobacterial culture, both on solid and liquid media, remains the “gold standard” for TB diagnosis, with an excellent correlation with clinical diagnosis. It is essential for performing phenotypic drug susceptibility testing and for molecular methods used in epidemiology of tuberculosis. The diagnostic delay inherent in any culture represents a limitation, especially for mycobacteria, which require longer incubation times.

The End TB Strategy, endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO), put forward initiatives to reduce the global impact of TB. Some measures are aimed at “finding the missing cases”, which are crucial for breaking transmission chains, improving contact investigations and incorporating rapid molecular assays as the initial diagnostic test for tuberculosis.3 These assays improve healthcare quality by allowing for early detection of TB cases, including paucibacillary patients; furthermore, some of them are designed to provide objective information regarding the presence/absence of mutations in genes associated with resistance to first and second-line anti-tuberculosis drugs. This would enable early identification of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and pre-extensively drug-resistant TB (pre-XDR-TB) cases, which is crucial for the clinical management of these patients.

In the updated WHO tuberculosis guidelines, recommendations for molecular diagnostic tests evaluated in 2020 and 2021 are assessed and defined according to the type of technology used, the complexity of the test (considering equipment requirements and technical skills), and the diagnostic objective (TB, resistance to first or second-line drugs, or both).4

This study prospectively compares five commercial molecular biology platforms based on real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) technology within a routine laboratory setting, with the objective of helping and enhancing the implementation of these platforms in every mycobacterial laboratory for the rapid diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC).

MethodsProspective observational study carried out in Asturias (Spain), a region with a population of one million inhabitants and a tuberculosis incidence rate of less than 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. The inclusion criteria was to select the first sample received from patients attended in the Pulmonology and Internal Medicine departments with no previous history of TB, among all samples routinely received in the mycobacterial laboratory of the Central University Hospital of Asturias. Samples from primary care or other departments were not included. The sample collection lasted 50 days, starting on November 3rd and ending on December 22nd.

Sterile samples were concentrated by centrifugation. Non-sterile samples underwent a decontamination-digestion pretreatment using the commercial kit BBL Mycoprep Kit (Becton Dickinson). Five milliliters (mL) of re-suspended pellets were homogenized and divided into 0.5mL aliquots, prepared for each diagnostic technique used in this study: fluorescence microscopy, RT-PCRs and mycobacterial culture (BACTEC MGIT960 (Becton Dickinson), VersaTREK (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Löwenstein–Jensen (Oxoid)). Liquid and solid media were incubated for a minimum of 6 and 8 weeks, respectively, before considering them negative.

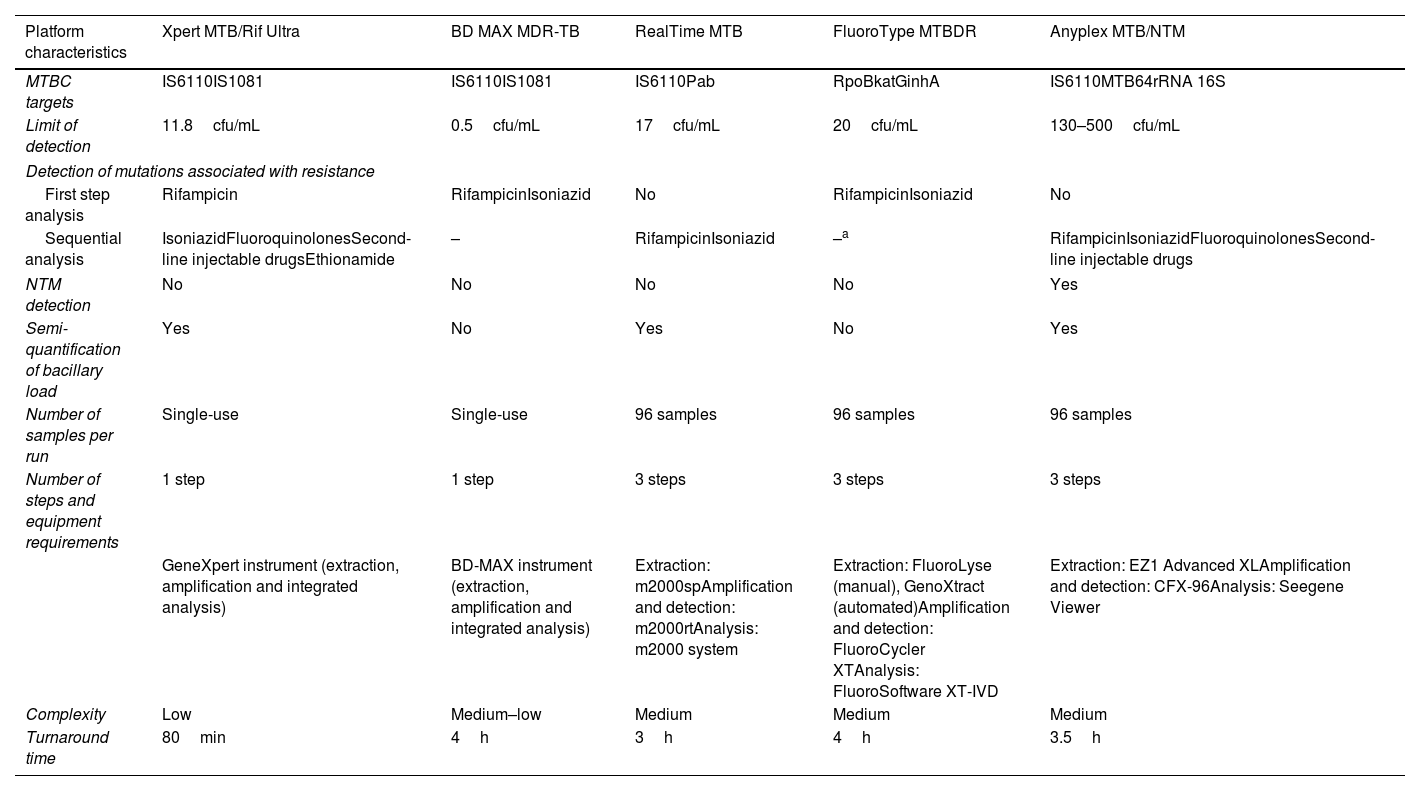

Parallel and blinded analyses were performed for each sample to compare five molecular diagnostic platforms: Xpert MTB/Rif Ultra (Cepheid); BD MAX MDR-TB (Becton Dickinson), RealTime MTB (Abbott), FluoroType MTBDR (Bruker-Hain Diagnostics), and Anyplex MTB/NTM (Seegene). The characteristics of each platform are shown in Table 1.

Operational characteristics of commercial real-time polymerase chain reaction assays analyzed.

| Platform characteristics | Xpert MTB/Rif Ultra | BD MAX MDR-TB | RealTime MTB | FluoroType MTBDR | Anyplex MTB/NTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTBC targets | IS6110IS1081 | IS6110IS1081 | IS6110Pab | RpoBkatGinhA | IS6110MTB64rRNA 16S |

| Limit of detection | 11.8cfu/mL | 0.5cfu/mL | 17cfu/mL | 20cfu/mL | 130–500cfu/mL |

| Detection of mutations associated with resistance | |||||

| First step analysis | Rifampicin | RifampicinIsoniazid | No | RifampicinIsoniazid | No |

| Sequential analysis | IsoniazidFluoroquinolonesSecond-line injectable drugsEthionamide | – | RifampicinIsoniazid | –a | RifampicinIsoniazidFluoroquinolonesSecond-line injectable drugs |

| NTM detection | No | No | No | No | Yes |

| Semi-quantification of bacillary load | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Number of samples per run | Single-use | Single-use | 96 samples | 96 samples | 96 samples |

| Number of steps and equipment requirements | 1 step | 1 step | 3 steps | 3 steps | 3 steps |

| GeneXpert instrument (extraction, amplification and integrated analysis) | BD-MAX instrument (extraction, amplification and integrated analysis) | Extraction: m2000spAmplification and detection: m2000rtAnalysis: m2000 system | Extraction: FluoroLyse (manual), GenoXtract (automated)Amplification and detection: FluoroCycler XTAnalysis: FluoroSoftware XT-IVD | Extraction: EZ1 Advanced XLAmplification and detection: CFX-96Analysis: Seegene Viewer | |

| Complexity | Low | Medium–low | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Turnaround time | 80min | 4h | 3h | 4h | 3.5h |

When growth was detected in culture media, the initial identification of MTBC was confirmed by the TB Ag MPT64 immunochromatographic test (SD-BIOLINE). In positive cultures with negative MPT64 antigen, the INNO-LiPA MYCOBACTERIA V2 and Genotype Mycobacterium CM/AS assays (Bruker-Hain Diagnostics) were used for non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) identification. For phenotypic drug susceptibility testing against first-line anti-tuberculosis drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin), the proportions method on SIRE-Bactec MGIT medium (Becton Dickinson) was used, as well as for pyrazinamide, interpreting results according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria.

The validity, reliability, and safety of each molecular platform were analyzed by calculating sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative likelihood ratios. The final result of the mycobacterial culture was considered the “gold standard” for the microbiological diagnosis of tuberculosis. Cohen's Kappa coefficient and Landis and Koch classification were used to evaluate the agreement rate between RT-PCR and mycobacterial culture.

On the other hand, the time to positivity (TTP) of cultures in days was compared to the semi-quantification data of the bacillary load, by cycle threshold value (Ct) or interpretation, in molecular assays that provide such information.

ResultsEighty respiratory samples (RS) (68 sputum samples, 10 bronchial aspirates and 2 bronchoalveolar lavages) and 20 non-respiratory samples (NRS) (10 urine, 5 sterile fluids, 2 abscess, 1 bone marrow, 1 stool, and 1 tissue biopsy) were finally included. There were 76 samples from male patients and the remaining 24 from female patients, with ages ranging from 18 to 91 years (mean, 62.5±19.4; median, 68; mode, 40). The underlying pathology of these patients and the clinical data provided for the study of mycobacteria were: hemoptisis (16%), pneumonia (15%), exacerbated COPD (12%), bronchiectasis (9%), general syndrome (7%), fever of unknown origin (5%), radiographic abnormalities (7%), microhematuria (4%), ascites (4%), respiratory infection (4%), pleural effusion (3%), chronic cough (3%), disuria (2%), cystic fibrosis (2%), HIV (1%), chronic renal failure (1%), pericardial effusion (1%), pneumoconiosis (1%), interstitial lung disease (1%), epididymitis (1%), and colitis (1%).

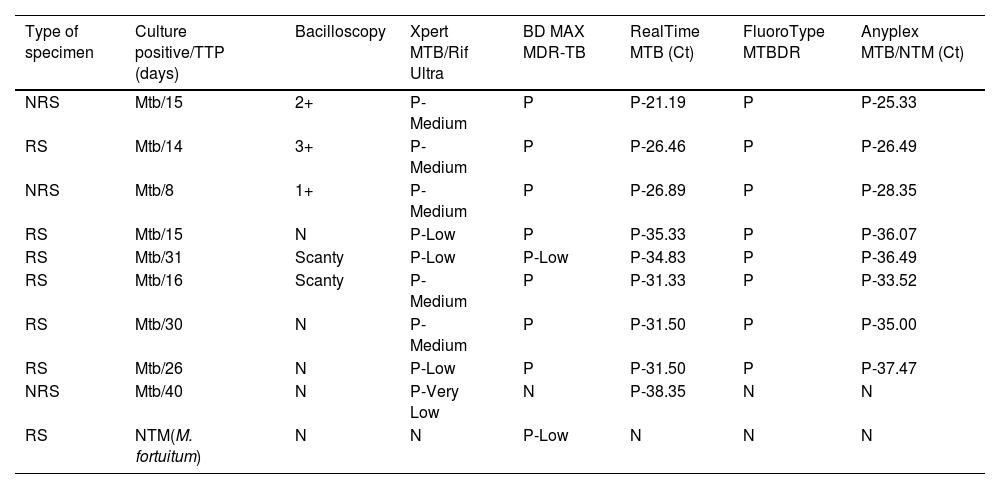

Of all the samples finally included, 9% had positive cultures for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) (6 RS, 3 NRS) and 90% had negative cultures (73 RS, 17 NRS). Only in one case a NTM species was isolated from a RS in culture, identified as Mycobacterium fortuitum. A mixed infection (NTM+Mtb) was excluded, as one of the two liquid media (BACTEC MGIT960) and solid media completed the incubation period and were reported negative. For samples with positive culture (Mtb and NTM), the estimation of bacillary load through bacilloscopy, culture's TTP and RT-PCR results are shown in Table 2.

Comparison of bacillary loads between microscopy, culture's time to positivity and cycle threshold value/interpretation data provided by molecular platforms.

| Type of specimen | Culture positive/TTP (days) | Bacilloscopy | Xpert MTB/Rif Ultra | BD MAX MDR-TB | RealTime MTB (Ct) | FluoroType MTBDR | Anyplex MTB/NTM (Ct) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS | Mtb/15 | 2+ | P-Medium | P | P-21.19 | P | P-25.33 |

| RS | Mtb/14 | 3+ | P-Medium | P | P-26.46 | P | P-26.49 |

| NRS | Mtb/8 | 1+ | P-Medium | P | P-26.89 | P | P-28.35 |

| RS | Mtb/15 | N | P-Low | P | P-35.33 | P | P-36.07 |

| RS | Mtb/31 | Scanty | P-Low | P-Low | P-34.83 | P | P-36.49 |

| RS | Mtb/16 | Scanty | P-Medium | P | P-31.33 | P | P-33.52 |

| RS | Mtb/30 | N | P-Medium | P | P-31.50 | P | P-35.00 |

| RS | Mtb/26 | N | P-Low | P | P-31.50 | P | P-37.47 |

| NRS | Mtb/40 | N | P-Very Low | N | P-38.35 | N | N |

| RS | NTM(M. fortuitum) | N | N | P-Low | N | N | N |

RS, respiratory sample; NRS, non-respiratory sample; TTP, time to positivity; Ct, cycle threshold value; Mtb, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; NTM, nontuberculous mycobacteria; N, negative; P, positive.

Scanty: 1–9 AFB/300 fields; 1+: 1–9 AFB/100 fields; 2+: 1–9 AFB/10 fields; 3+: 1–9 AFB/single field; 4+: >9 AFB/single field.

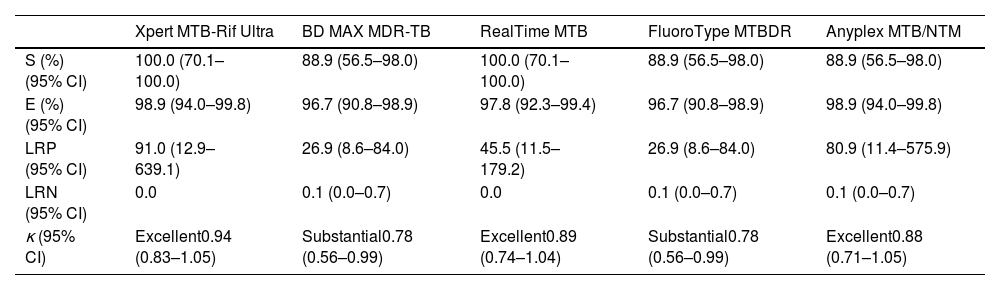

Fluorescence microscopy as initial diagnostic test showed a sensitivity of 55.6% (95%CI, 26.7–81.1) and a specificity of 100.0% (95.9–100.0), with an agreement rate with mycobacterial culture of 0.69 (0.40–0.99). Attending to probability ratios, the negative likelihood ratio for fluorescence microscopy was 0.44 (0.21–0.92) (positive likelihood ratio was not considered, as this technique cannot discriminate between Mtb AFB from NTM AFB). On the other hand, the intrinsic capability to diagnose or rule out tuberculosis of the five rapid molecular assays included in this study, and the overall concordance with mycobacterial culture are shown in Table 3. The proportion of discordant RT-PCR positive/culture Mtb-negative results (false-positive rates) was 1.0% (0.2–6.0) for Xpert and Anyplex, 2.0% (0.6–7.7) for RealTime, and 3.0% (1.1–9.2) for BD MAX and FluoroType. There were no discordant RT-PCR negative/culture Mtb-positive results in Xpert and RealTime platforms, whereas the false-negative rate for Anyplex, BD MAX and FluoroType was 11.0% (2.1–43.5).

Diagnostic accuracy assessment of commercial real-time polymerase chain reaction assays analyzed.

| Xpert MTB-Rif Ultra | BD MAX MDR-TB | RealTime MTB | FluoroType MTBDR | Anyplex MTB/NTM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (%) (95% CI) | 100.0 (70.1–100.0) | 88.9 (56.5–98.0) | 100.0 (70.1–100.0) | 88.9 (56.5–98.0) | 88.9 (56.5–98.0) |

| E (%) (95% CI) | 98.9 (94.0–99.8) | 96.7 (90.8–98.9) | 97.8 (92.3–99.4) | 96.7 (90.8–98.9) | 98.9 (94.0–99.8) |

| LRP (95% CI) | 91.0 (12.9–639.1) | 26.9 (8.6–84.0) | 45.5 (11.5–179.2) | 26.9 (8.6–84.0) | 80.9 (11.4–575.9) |

| LRN (95% CI) | 0.0 | 0.1 (0.0–0.7) | 0.0 | 0.1 (0.0–0.7) | 0.1 (0.0–0.7) |

| κ (95% CI) | Excellent0.94 (0.83–1.05) | Substantial0.78 (0.56–0.99) | Excellent0.89 (0.74–1.04) | Substantial0.78 (0.56–0.99) | Excellent0.88 (0.71–1.05) |

S, sensitivity; E, specificity; LRP, positive likelihood ratio; LRN, negative likelihood ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

κ, Cohen's Kappa coefficient. Landis and Koch classification: 0.01–0.20, slight agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair; 0.41–0.60, moderate; 0.61–0.80, substantial; 0.80–1.00, excellent.

The semi-quantification data of bacillary loads recovered from Xpert, RealTime and Anyplex assays were as follows: in Mtb-positive samples and TTP≤15 days, Ct averages were 27.46 and 29.06 in RealTime and Anyplex, respectively; Xpert interpreted 75% as “Medium” and 25% as “Low”. For samples with TTP>15, Ct averages were 33.50 and 35.62 in RealTime and Anyplex; Xpert interpreted 50% as “Medium” and 50% as “Low”.

None of the five RT-PCR assays detected any mutations associated with drug resistance. Phenotypic drug sensitivity testing revealed that all nine Mtb strains were susceptible to isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, streptomycin and pyrazinamide.

DiscussionThe impact of molecular assays as an initial test for early diagnosis of tuberculosis has been evaluated in a WHO report, with evidence of a decrease in both time-to-diagnosis and time-to-treatment initiation, and an increase in the proportion of cured tuberculosis patients.5

During the early stages of tuberculosis, samples collected for microbiological diagnosis are likely to be paucibacillary. Managing these patients, suspected of having tuberculosis but with negative bacilloscopy, is complex, especially if the clinical presentation is atypical.6 In addition, a study showed that up to 35% of contacts of TB patients with negative bacilloscopy were later diagnosed with Mtb infection,7 revealing a significant risk of disease transmission in these cases. The accuracy of molecular assays to detect TB cases with lower bacillary loads has been reported in various publications, showing sensitivities between 40 and 80% and detection limits lower than the 5000–10,000cfu/mL required by bacilloscopy.8 Although this study included a limited number of NRS samples (presumably, samples with lower concentration of bacteria), 55.6% (5/9) of positive Mtb samples showed low bacillary loads (≤1–9 AFB/300 fields and culture's TTP≥15 days).

In our study, the overall sensitivity and specificity for all rapid molecular assays were above 88% and 96%, respectively. This resulted in a 30–40% improvement in sensitivity, compared to fluorescence microscopy as initial screening, and avoided diagnostic delays of between 8 and 30 days, considering the culture media's TTP.

Molecular testing with semiquantification of bacillary loads could enable the identification of the most contagious patients. In this regard, considering TTP as inversely proportional to bacillary load,9 we found that Ct lower than 30 for RealTime and Anyplex platforms corresponded to cultures with TTP≤15 days. On the other hand, we observed no correlation between Xpert Ultra interpretation and TTP of cultures, perhaps due to the concentration technology implemented in the cartridges.10 However, Martin-Higuera et al. demonstrated correlation with the lowest Ct among rpoB probes when an internal control-based correction factor was incorporated to minimize experimental variability.11

Most of the rapid molecular assays target the IS6110 region, highly specific for MTBC, to avoid possible false-positive results due to the presence of other mycobacteria in the sample. The number of samples with NTM growth in our study was limited, and it did not allow us to identify possible specificity issues in the molecular techniques used. However, it is worth noting that the sample with M. fortuitum growth tested positive in one of the molecular platforms. It has been described in the literature that some NTM strains may have elements in their DNA with significant homology to IS6110.12 Furthermore, global dissemination of some MTBC lineages with absence or a low number of IS6110 copies has been demonstrated.13 Although the impact on the specificity of RT-PCR against MTBC is presumably minimal, it is desirable for molecular assays to include additional targets to IS6110 to improve diagnostic performance.

Discrepant RT-PCR positive/culture Mtb-negative results should be analyzed with caution. Clinically, it is important to know if the patient has a previous history of TB or has initiated anti-tuberculosis treatment, as molecular techniques do not make a distinction between viable and non-viable bacilli.14 Intra-laboratory, possible cross-contamination in sample processing should be considered.15 In this regard, low-complexity molecular platforms, with fully integrated systems (extraction and amplification) in single-use cartridges and minimal sample manipulation, minimize this factor and require less technical training.4

In our study, the proportion of false positives was low (1.0–3.0%). In addition, the positive likelihood ratios calculated for the five platforms were above 10 (26.9–91.0), suggesting that the likelihood of TB patients having a positive PCR is 26.9–91.0 times higher compared to patients without infection. This illustrates the excellent discriminatory power of molecular assays in confirming tuberculosis infection. Our data are consistent with those published by Babafemi et al. in a meta-analysis, with different RT-PCR for MTBC detection, both pulmonary and extrapulmonary, inferring that it is an adequate method to confirm or exclude tuberculosis (positive and negative likelihood ratios, 43.0 and 0.16 in respiratory samples, and 29.82 and 0.33 in extrapulmonary samples).16

Our study has several limitations, including the low number of NRS samples analyzed, as well as the absence of MDR/XDR-TB strains, so we could not determine the performance of the molecular platforms studied in detecting mutations associated with resistance to anti-tuberculosis drugs. Implementing RT-PCR testing with identification and resistance detection in a single step (80min–4h) may be an advantage for the management of patients from geographic areas with a high prevalence of MDR/XDR-TB strains. Nevertheless, sequential analysis still represents a clinically relevant diagnostic improvement in turnaround time (TAT) (4h for MTBC identification+4h for resistance mutation detection) compared to phenotypic testing (2–12 weeks).

All of these molecular assays are RT-PCR targeting known mutations against both first and second-line treatment drugs. However, the inability to detect mutations that confer resistance outside the target gene, or the detection of silent mutations, which are misinterpreted as phenotypically resistant, makes phenotypic resistance testing still necessary.17 Currently, next-generation sequencing (NGS) techniques combine the advantage of shorter TATs than phenotypic testing, along with an improvement in the scope of RT-PCRs, providing detailed information on multiple genetic regions of interest.18

Among WHO-recommended diagnostic testing platforms to be used as initial test for TB not included in our study are: Cobas® MTB and MTB RIF/INH (F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.), Truenat® MTB Plus and RIF Dx (Molbio Diagnostics Ltd.), Loopamp® MTBC detection (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd.) (loop-mediated isothermal amplification), and more recently, the new Xpert® MTB/XDR cartridge, and the Standard® M10 MTB/NTM and M10 MDR-TB cartridges (SD Biosensor INC.).19

In conclusion, this study's strength lies in its prospective comparison of a high number of wildly known rapid molecular assays with parallel-blinded analyses, enhancing result representativeness of the behavior of each platform in a laboratory routine. We aimed to assess the usefulness of molecular tools both for confirming cases with a diagnostic suspicion of TB and for excluding TB when it involved a differential diagnosis among other possible etiologies.

The global benefits of RT-PCR for TB screening are acknowledged. Molecular techniques are transforming and should continue to transform tuberculosis diagnosis. Furthermore, we believe they are essential in the context of public health alerts. They should be considered both for updating the case definition and for the rapid reporting of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis cases (MDR/RR-TB, preXDR-TB).20 Choosing the suitable platform for each laboratory requires considering qualitative, operational, epidemiological, and economic factors.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge Abbott and Bruker-Hain Diagnostics for providing reagents specifically for the study.