Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is an emerging tick-borne viral disease. It has been described in Spain in both ticks and humans. Until July 2024 most cases have been described in the central-western part of the Iberian Peninsula. This study aims to assess the seroprevalence of antibodies against CCHF virus (CCHFV) in humans in the area that has reported the highest number of cases in Spain.

MethodsThe study was conducted to estimate the seroprevalence of antibodies against CCHFV antibodies among patients referred to a hospital located in the central-western area of Spain, an endemic area for CCHFV of Spain. Patients were recruited from April 1, 2023, to June 30, 2023. A commercial ELISA was used to detect serum antibodies against the CCHFV.

ResultsWe screened 658 samples from 370 (56.2%) men, with a mean (±SD) age of 58.6 years (±14.3). Of these, 4 were IgG positive, representing an IgG seropositivity of 0.6% (95% CI, 0.01–1.19). None of these four patients recalled having a clinical picture that strongly suggested CCHF.

Over the study period, in the population analysed in an area with circulation of CCHFV the seroprevalence of antibodies was 0.6%.

ConclusionOur results suggest active circulation of the virus in humans in western Spain. Although the risk of developing CCHF is currently considered low, physicians should be alert to the imminent possibility of developing new cases of CCHF.

La fiebre hemorrágica de Crimea-Congo (FHCC) es una enfermedad viral emergente transmitida por garrapatas. En España ha sido descrita tanto en garrapatas como en humanos. Hasta julio de 2024 la mayoría de los casos se han descrito en el centro-oeste de la península Ibérica. Este estudio tiene como objetivo evaluar la seroprevalencia de anticuerpos frente al virus de la FHCC (VFHCC) en humanos en el área que ha reportado un mayor número de casos en España.

MétodosEstudio de la seroprevalencia de anticuerpos frente al VFHCC entre pacientes remitidos a un hospital ubicado en la zona centro-oeste de España. Los pacientes fueron reclutados desde el 1 de abril de 2023 hasta el 30 de junio de 2023. Se utilizó un ELISA comercial para detectar anticuerpos séricos frente al VFHCC.

ResultadosExaminamos 658 muestras de 370 (56,2%) hombres, con una media de edad (±DE) de 58,6 años (±14,3). De estos, 4 fueron positivos para IgG, lo que representa una seropositividad para IgG del 0,6% (IC 95%: 0,01-1,19). Ninguno de los 4 pacientes recordaba haber tenido un cuadro clínico que sugiriera fuertemente FHCC. En el periodo de estudio, en la población estudiada, en un área en la que circula el VFHCC existe una seroprevalencia del 0,6%.

ConclusiónNuestros resultados sugieren una circulación activa del VFHCC en humanos en el oeste de España. Aunque en la actualidad el riesgo de desarrollar una FHCC se considera bajo, los médicos deben estar alerta ante la inminente posibilidad del desarrollo de nuevos casos de FHCC.

Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a tick-borne viral zoonotic disease caused by CCHF virus (CCHFV), a negative single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Orthonairovirus in the family Nairoviridae.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has included CCHF in its prioritized list of diseases with the greatest risk to public health due to its epidemic potential and the lack of vaccines and antiviral treatments of proven efficacy.2 CCHFV is transmitted to humans by bites of infected ixodid ticks. Although the virus has been found in different species of ticks, the only currently recognized vectors are ticks of the genus Hyalomma.

CCHF is an emerging infectious disease, due, among other reasons, to the progressive spread of its main vector. This infection can also be transmitted between humans through contact with different infected fluids, and nosocomial transmission has also been described.3

The spectrum of clinical manifestations of CCHF ranges from subclinical or mild illness (including fever, headache, myalgia, malaise, sore throat, dizziness, vomiting, nausea, abdominal pain, conjunctivitis, and photophobia)4 to acute infection with haemorrhage, multiorgan failure and death.5 Laboratory parameters are frequently altered, with leukopenia, thrombocytopaenia and elevated serum liver transaminases.6

Classically, CCHFV has been identified in Africa, Asia and Europe in territories located south of the 50th North parallel and in areas inhabited by its vector.7–9 It is absent only in North America, South America, and Australia. In recent years, important changes in the epidemiology of CCHFV have been noted, and climate change has been identified as one of the factors driving the circulation of the virus.

In Europe, this virus has caused major outbreaks in the eastern region.10 Nevertheless, CCHF is currently considered endemic in areas of southwestern Europe, and human cases have been identified in western Spain since the summer of 2013.11–14 Seventeen human cases have been identified in Spain, from the first case up to August 2024, four of them this last year, 7 of which were in the province of Salamanca, mainly in the Bejar area.15 The CCHFV genotypes detected in Spain from patients in 2016 and 2018 were genotypes III, IV and V.11,14 Strong clinical suspicion is required for rapid and accurate diagnosis, supportive treatment initiation if needed, and biosafety measure activation to prevent transmission. The objective of this study was to measure the presence of antibodies against CCHFV in humans in a central-western area of Spain endemic for CCHFV.

MethodsStudy type and data collectionA seroepidemiological study was conducted to determine the seroprevalence of anti-CCHFV antibodies (IgG and IgM) among patients from the nursing consultation (extraction of analysis for any reason of primary and/or specialized care) referred to Virgen del Castañar Hospital. This hospital covers the southwestern part of the province of Salamanca, including the Béjar area (Spain). It is incorporated into the University Hospital of Salamanca. It has an emergency service 24h a day throughout the week, and all medical and surgical specialties for adults are provided 24h a day. It provides coverage/health care to a population of 12,021 inhabitants, including 5697 males and 6324 females (INE 2023: https://ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=2891).

Patients were prospectively recruited from April 1, 2023, to June 30, 2023. The only selection criterion was that patients agreed to participate in the study. All epidemiological, clinical, and analytical parameters were systematically recorded at a single point in time, i.e., the hospital admission date, following a predefined clinical protocol. This protocol included variables such as gender, age, symptoms, contact with CCHF patients (period of less than 10 years), contact with pets or professional animals and CCHFV Ig G.

Immunological assayAntibodies against CCHFV were detected via a semiquantitative ELISA microplate assay (Euroimmun Medizinische Labourdiagnostika, Germany). A Dinex DS2® automatic ELISA analyser (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA, USA) was used for assay automation. The results were evaluated according to the manufacturer's instructions. A result was considered negative when it was below 80% of the cut-off point; results between 80% and 110% of the cut-off point were considered doubtful and not considered seropositive, and only results >110% of the cut-off point were considered seropositive for CCHFV.

Statistical analysisAll data were statistically analysed using Jamovi statistical software. Seroprevalence was defined as the percentage (%) of individuals who tested positive for either the IgG or IgM subtype. The prevalence estimate is reported with a corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI). We calculated proportions for qualitative variables and means with standard deviations (SDs) and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs=Q3−Q1) for quantitative variables. To determine whether measurements from different groups were independent, the chi-squared (χ2) test for large sample sizes and Fisher's exact test for small sample sizes were applied. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare means between groups. Due to the low number of positive events, we were unable to perform regression analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance for all tests.

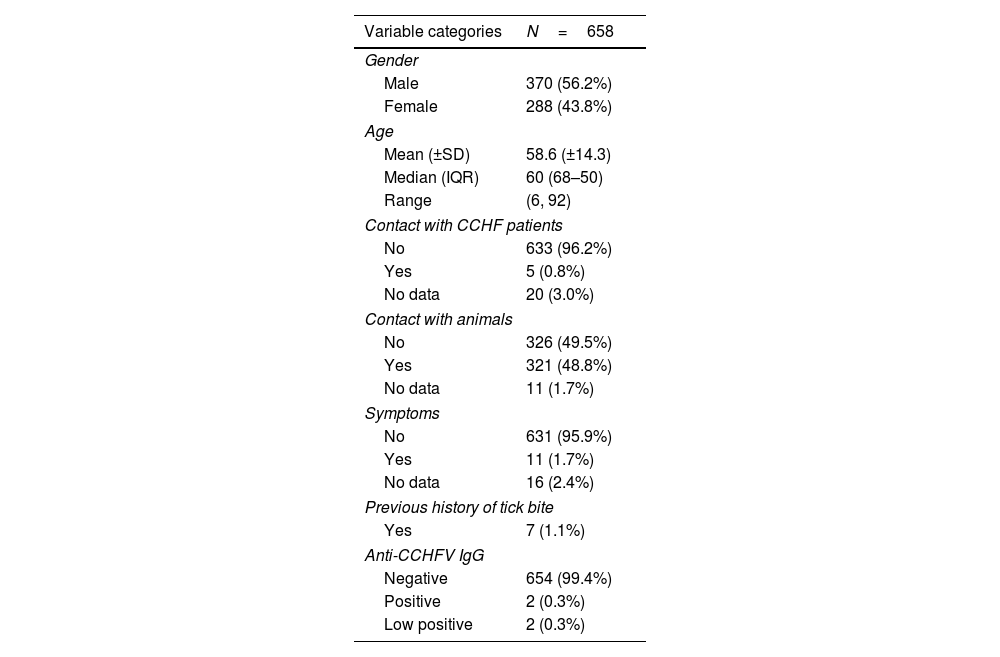

ResultsSix hundred and fifty-eight (658) patients participated in this study. The sample included 370 (56.2%) men and 288 (43.8%) women. The mean age (±SD) of the study participants was 58.6 years (±14.3); the median age was 60 years [IQR: 68–50], ranging from 6 to 92 years (a single paediatric patient). Five (0.8%) patients reported having been in contact with persons with CCHF history, from as recently as one year prior (1 patient) to 10 years prior (1 patient). Half of the sample (321 patients, 48.8%) reported having contact with either domestic and companion animals: dogs, cats, horses, cows, sheep, goats, guinea pigs, rabbits, chickens and poultry. Only 9 patients had professional contact, and one patient had contact with hunting dogs. Seven (1.1%) patients reported a history of tick bites. A total of 11 (1.7%) patients reported various symptoms, including fever (3), local inflammation (4), and tularaemia with pulmonary involvement (1); 7 of them (1.1%) described symptoms associated with a tick bite. One patient with fever, headache and muscle pain required hospital admission. The main characteristics of the studied cohort are summarized in Table 1.

Main cohort data.

| Variable categories | N=658 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 370 (56.2%) |

| Female | 288 (43.8%) |

| Age | |

| Mean (±SD) | 58.6 (±14.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 60 (68–50) |

| Range | (6, 92) |

| Contact with CCHF patients | |

| No | 633 (96.2%) |

| Yes | 5 (0.8%) |

| No data | 20 (3.0%) |

| Contact with animals | |

| No | 326 (49.5%) |

| Yes | 321 (48.8%) |

| No data | 11 (1.7%) |

| Symptoms | |

| No | 631 (95.9%) |

| Yes | 11 (1.7%) |

| No data | 16 (2.4%) |

| Previous history of tick bite | |

| Yes | 7 (1.1%) |

| Anti-CCHFV IgG | |

| Negative | 654 (99.4%) |

| Positive | 2 (0.3%) |

| Low positive | 2 (0.3%) |

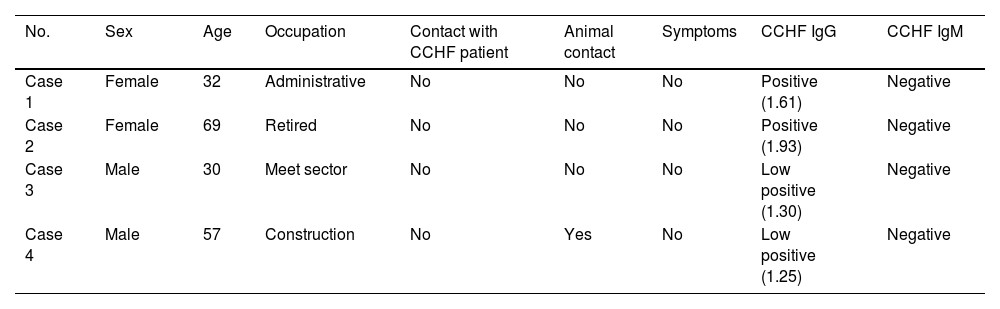

CCHFV IgG antibodies were detected in 4 samples, with values ranging between 125% and 193% of the cut-off. These data (4 IgG+/658 samples) indicated an IgG seropositivity of 0.6% (95% CI, 0.01–1.19) in the study sample. Two seropositive samples were from females (2/288), IgG seropositivity 0.7% (95% CI, −0.26 to 1.66), and two seropositive samples were from males (2/370), IgG seropositivity 0.5% (95% CI, −0.22 to 1.22). IgM was negative for all patients. The demographic and clinical profiles of these patients are described in Table 2. None of the four IgG-positive patients had a previous history of CCHF or contact with CCHF patients, and only one patient had contact with animals. All of the patients were asymptomatic. There were no statistically significant differences between the groups of patients (IgG seropositive versus the rest of the sample) with regard to the variables age (P=0.237) and sex (P=0.158). In summary, over the study period, in the population analysed in an area with circulation of CCHFV the seroprevalence of antibodies was 0.6%.

Individualized description of patients with IgG positive for CCHFV.

| No. | Sex | Age | Occupation | Contact with CCHF patient | Animal contact | Symptoms | CCHF IgG | CCHF IgM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Female | 32 | Administrative | No | No | No | Positive (1.61) | Negative |

| Case 2 | Female | 69 | Retired | No | No | No | Positive (1.93) | Negative |

| Case 3 | Male | 30 | Meet sector | No | No | No | Low positive (1.30) | Negative |

| Case 4 | Male | 57 | Construction | No | Yes | No | Low positive (1.25) | Negative |

This study was conducted on people who live in Béjar (province of Salamanca, central-western Spain), to describe the prevalence of CCHF antibodies in the population of an endemic area in Spain and to evaluate the potential circulation of CCHFV. Palomar et al. previously carried out a study in which 228 serum samples from humans with regular contact with ticks in Caceres, an area near Bejar, were collected, but no positive serum samples were detected.16

Classically, the geographical expansion of vector-borne communicable diseases to Europe is associated with several factors, including an increase in the global annual average temperature,17 human displacement, an increase in population density in some vulnerable zones,18 legal and illegal trade of animals and animal products19 and patterns of land use for agriculture.20 This phenomenon has increased in recent years. However, the impact of human migration on vector-borne diseases in Europe has not yet been analysed in depth.

Studies carried out in Spain in healthy donors21 and in patients with febrile syndrome14 in the emergency room showed a serological prevalence of past CCHFV infection of up to 1.16% and 2.22%, respectively, which is similar to that reported in the 1980s by Filipe et al. in southern Portugal.22

However, other studies in southwestern and central Spain did not find antibodies against the virus.16,23 These discrepancies may be conditioned by different factors, such as the analytical methodology used, but also the area and population studied. The prevalence in this study is also similar to that found in other European countries with a very low incidence, such as Hungary24 and Greece.25 Taken together, these data suggest that CCHF is underdiagnosed, probably due to the high frequency of asymptomatic patients, which exceeded 88% in different series.4,5 In this way, all patients diagnosed in Spain were diagnosed within the last 10 years; most of them were diagnosed within the last 4 years, 30% were diagnosed retrospectively, and the fatality rate of CCHF was as high as 30%.

Previous studies indicate that birds seem to be involved in the transmission of the African genotype III virus in Spain.26 In turn, domestic animals such as pigs have been imported from Eastern countries, and there could be a relationship with the CCHF epidemiology of European and Asian strains, particularly with those of genotype V and/or IV. Interestingly, in recent studies, multiple strains of CCHFV were detected in ticks in Spain, even within the same geographical area inside the country, in line with our findings.27,28 From a clinical point of view, in Spain, strains of genotypes III and IV have been associated with higher rates of mortality than strains of genotype V, in line with our observations, though the number of patients remains very limited.

Spain represents a risk area for continuous entry of CCHFV belonging to different clades due to its proximity to Africa29 and because of the adequate conditions available for maintaining their circulation. For example, (i) Spain is a mandatory transit site for migratory birds from endemic areas, and these migratory birds may transport infected larvae and nymphs of hard ticks from North Africa30; (ii) Spain, especially areas with a more temperate climate, constitutes a favourable environment for the vector involved in transmission, which facilitates widespread vector presence; (iii) ticks may establish an ecological environment in this zone where they become adults and feed on ungulates or humans, maintaining an enzootic cycle31; and (iv) a variety of vertebrate animals might be able to act as amplifying hosts and thereby increase the risk of spreading the virus.

In conclusion, our results suggest active circulation of the virus in humans in western Spain. Although the risk of developing CCHF is currently considered low, physicians should be alert to the imminent possibility of developing new CCHF cases.

CRediT authorship contribution statementJosue Pendones Ulerio, Amparo López Bernús, Rufino Álamo, Antonio Muro, Juan Luis Muñoz Bellido and Moncef Belhassen-Garcia have conceived and/or designed the main manuscript. Belen Vicente and Beatriz Rodriguez Alonso have acquired data of the work. Montserrat Alonso-Sardón has analysed and interpreted data of the work and prepared Tables 1 and 2. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Helena Miriam Lorenzo Juanes and Moncef Belhassen-Garcia. All authors have reviewed the work critically for important intellectual content, approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical approvalThe study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Investigation with Drugs of the University Hospital of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain (CEIm PI 91 09/2017). All procedures described were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the Revised Declaration of Helsinki of 2013. All clinical and epidemiological data were anonymized.

FundingThis study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI22/01721 and cofunded by the European Union.

Declaration of competing interestAll the authors declare no potential conflicts of interest and no financial interests.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank the population of Béjar and its health workers and María Paz Sánchez-Seco for their invaluable help in revising this manuscript.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to individual privacy could be compromised, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.