Dientamoeba fragilis is a protozoan of the gastrointestinal tract, very prevalent in our environment and responsible for diverse clinical symptoms mainly abdominal pain, diarrhoea and eosinophilia, although some infected patients are asymptomatic. Since the first description just a century ago, there are many unanswered questions: its different morphologies and the role of each of them, its actual prevalence, the mode of transmission, its pathogenicity, or the treatment of choice, continue to be source of controversy. Risk factors associated with infection by D. fragilis are: contact with children, residence in a rural area, and co-infection by Enterobius vermicularis. New molecular diagnostic techniques in the form of commercial multi-diagnostic panels are now considered first choice techniques. Paromomycin show higher cure rates, than metronidazole.

Dientamoeba fragilis es un protozoo del tracto gastrointestinal, muy prevalente en nuestro medio, responsable de diversos síntomas clínicos, principalmente dolor abdominal, diarrea y eosinofilia, aunque algunos pacientes son asintomáticos. Desde su primera descripción hace apenas un siglo, son muchas las preguntas sin respuesta: sus diferentes morfologías y el papel de cada una de ellas, su prevalencia real, el modo de transmisión, su patogenicidad, o el tratamiento de elección, siguen siendo fuente de controversia. Se han identificado como factores de riesgo asociados a la infección por D. fragilis el contacto con niños, la residencia en zona rural y la coinfección por Enterobius vermicularis. Las nuevas técnicas de diagnóstico molecular en forma de paneles comerciales de diagnóstico múltiple se consideran en este momento técnicas de primera elección. La paromomicina muestra tasas de curación más elevadas que el metronidazol.

Dientamoeba fragilis is a protozoan of the gastrointestinal tract, very prevalent in our environment and responsible for diverse clinical symptoms, mainly digestive.1 Since the first description just a century ago, there are many unanswered questions: its different morphologies and the role of each of them, its actual prevalence, the mode of transmission, its pathogenicity, or the treatment of choice, continue to be source of controversy. Given its high prevalence in our environment and the doubts that still surround it, a systematic review of the characteristics of this protozoan is carried out, with special emphasis on its clinical features and treatment.

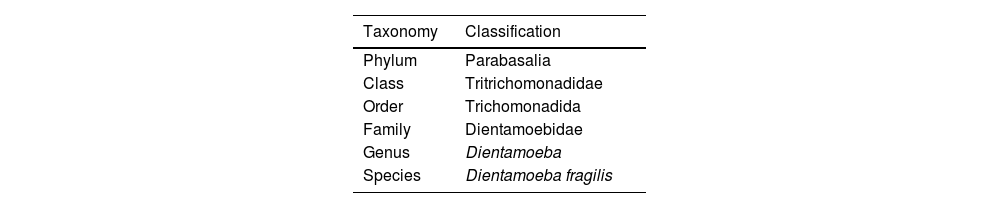

Classification and taxonomyD. fragilis is classified under the phylum Parabasalia, class Tritrichomonadidae, order trichomonadida, family dientamoebidae, genus Dientamoeba1,2 (Table 1). It has an oval trophozoite between 5 and 15μM3 which shows active movement due to the emission of hyaline ‘fan-shaped’ pseudopods.1,4 Trophozoites have 1–4 small nuclei (2–3μM) containing 3–8 chromatin granules.5 The presence of a binucleate form with the nuclei joined by a desmosome or centrodesmosome is the most frequent (60–80%).1,3

Classically, D. fragilis had been considered to lack precyst and cyst stages. Subsequently, Stark et al.6 have described cystic forms with a prevalence of 0.01%, and precystic or pseudocyst forms with a prevalence of 32.6%.6 The precystic cyst is a spherical structure between 3.5 and 5μm in diameter with one or two nuclei.3,6 The cysts are characterised by a clear zone (peritrophic space) and a wall of about 5μm in diameter.6 They are binucleate, and each nucleus contains a large central karyosome and is surrounded by a thin nuclear membrane.3 The nucleus is usually fragmented into distinct chromatin granules.6 Two genotypes of D. fragilis have been described, with genotype 1 being the most common, but no differences in pathogenicity have been demonstrated.7 However, studies using High Resolution Melt (HRM) analysis have detected the presence of four different profiles.8 Profile 1 was predominant (50%), profile 2 was present in 20% of the samples, and profiles 3 and 4 were detected in 16.7% and 13.4% respectively. Most patients with profile 1 (73.4%) and profile 4 (75%) had chronic intermittent diarrhoea. All patients with D. fragilis profile 2 had acute diarrhoea, and patients with D. fragilis profile 3 had alternating bowel habit, with phases of diarrhoea and constipation. Although all differences were statistically significant,8 the clinical significance of these variations remains to be determined.

Biology and life cycleSeveral mechanisms of transmission of D. fragilis have been postulated.1,3,5,6,9 The classical faecal–oral transmission model implies that D. fragilis trophozoites multiply in the small intestine of the host (humans or animals including domestic, farm and wild animals) by binary fission, and are subsequently excreted via faeces. These trophozoites contaminate food and/or water, which are subsequently ingested by other human or animal hosts, closing the cycle and perpetuating the infection.1,3 Supporting this type of transmission, a recent study by Stark et al.,9 demonstrates the role of Dientamoeba cysts in the transmission of Dientamoeba.

The role that contaminated water plays in this cycle is controversial. Stark et al.10 analysed environmental samples, including fifty drinking water samples, fifteen lake water samples, ten pond water samples, ten river water samples, three treated wastewater samples and four untreated wastewater samples and demonstrated the presence of D. fragilis in one of the untreated wastewater samples. More recently, Kauppinen A et al.11 described an outbreak of gastroenteritits caused by the isolation of Sapovirus from drinking water in which D. fragilis is detected in a sample and in clinical samples from patients. However, given that it is not possible to determine whether the patients were previously infected and the presence of other pathogens, the authors themselves point out that it is difficult to draw conclusions about the role of Dientamoeba in the outbreak.

In addition to this classical form, alternative forms of transmission have been postulated, such as zoonotic transmission, transmission via Enterobius vermicularis eggs12–15 and direct person-to-person transmission.10,16

The possibility of transmission via E. vermicularis eggs is supported by the high co-infection rates detected and the identification of D. fragilis DNA inside E. vermicularis eggs.12–14 Ogren et al.12 detected D. fragilis DNA by PCR in 18 (85%) of 21 samples of E. vermicularis eggs collected from patients with D. fragilis, and Roser et al.13 detected D. fragilis DNA from the sterilised surface of E. vermicularis eggs. All these findings support the role of E. vermicularis in D. fragilis transmission; however, the presence of DNA within the eggs does not confirm the existence of live organisms, so further experimental studies are necessary to prove this point.

On the other hand there is a surprising frequency of co-infection by both pathogens, 9 times higher than would be expected by chance in patients infected by D. fragilis. Girginkardeşer et al.16 compared 187 patients with E. vermicularis infection versus 126 with D. fragilis infection and found that in the former group 9.6% were co-infected while the co-infection rate in the latter group was 25.4%. This unique relationship between the two pathogens could be responsible for the more efficient transmission of D. fragilis, given the ability of E. vermicularis eggs to remain prolonged in the environment, even in adverse conditions, which would favour the survival of the protozoan. Other studies, however, do not demonstrate this correlation. For example, Stark et al.9 did not find coinfection by E. vermicularis in an Australian population of different ages. Therefore, at this point the role of E. vermicularis in the transmission of Dientamoeba remains to be elucidated.

The mechanism of direct person-to-person transmission is supported by the high prevalences (between 30 and 52%) of infected contacts found in previous research.10,16 Previous studies of our working group16 show a prevalence in contacts of 50.5%, being the infection in them associated with the presence of children in the family and coinfection with E. vermicularis.

Regarding zoonotic transmission, Stark et al.10 have studied samples from cats, dogs, birds and pigs, without identifying the presence of D. fragilis in any of them. Chan et al.18 examined a total of 420 animal samples, including horses, cats, dogs and pigs among others, and detected D. fragilis by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in only one dog and one cat. The low prevalence (0.48%) of D. fragilis in the animals tested in these studies contrasts with the high prevalence observed in humans, and the possibility of a reverse zoonosis cannot be ruled out. However, data collected in animals should be treated with caution, given the possibility of false positive results due to cross-reactivity with other trichomonads present in animals.

Prevalence and epidemiologyDientamoeba has been reported in both developed and developing countries with prevalences between 5 and 68% depending on the country and the techniques used,19–21 and is currently recognised as the most prevalent protozoan after Blastocistyshominis.1 The prevalence rates observed in the different studies are highly variable depending on the population analysed, but above all on the sensitivity of the diagnostic method used, being higher in those using PCR both conventional and multiple. Table 1 of the supplementary material shows the different prevalences found according to the diagnostic method used.

Regarding the influence of age and gender on the incidence of D. fragilis infection, the results reflected in the different studies are variable. Most studies describe a peak incidence in paediatric age and a second, smaller peak in young adults (ages 30–40 years).19,22,23 In relation to gender, most studies describe a higher prevalence in women,24 although only significant in adults of parental age.19 However, other studies showed no difference between males and females, or even described a higher incidence in males, especially at ages below 20 years.23

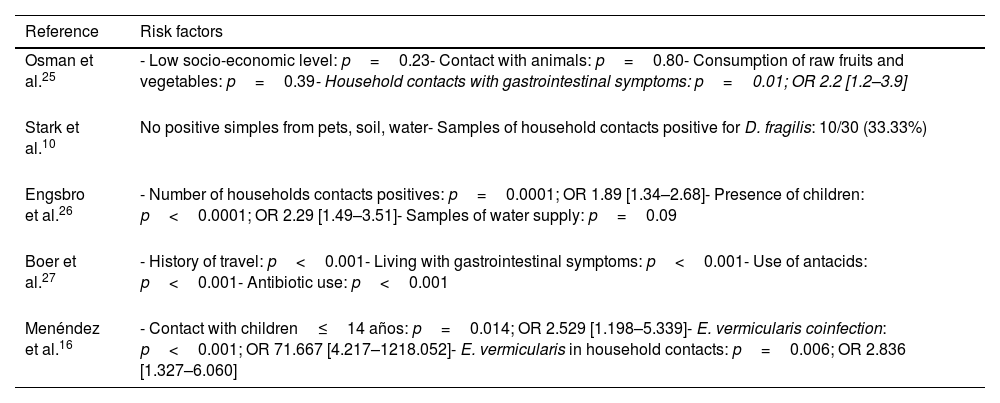

Risk factorsSeveral risk factors have been identified in relation to D. fragilis infection (Table 2). The presence of D. fragilis within the household contacts has been considered a risk factor for acquiring the infection. Osman et al.25 conducted a study in 249 children, describing the presence of D. fragilis in 60.6% of them, and identified as the only risk factor the presence of cohabitants with gastrointestinal symptoms (p=0.01; OR 2.2 [1.2–3.9]).

Risk factors for D. fragilis infection identified in the different studies.

| Reference | Risk factors |

|---|---|

| Osman et al.25 | - Low socio-economic level: p=0.23- Contact with animals: p=0.80- Consumption of raw fruits and vegetables: p=0.39- Household contacts with gastrointestinal symptoms: p=0.01; OR 2.2 [1.2–3.9] |

| Stark et al.10 | No positive simples from pets, soil, water- Samples of household contacts positive for D. fragilis: 10/30 (33.33%) |

| Engsbro et al.26 | - Number of households contacts positives: p=0.0001; OR 1.89 [1.34–2.68]- Presence of children: p<0.0001; OR 2.29 [1.49–3.51]- Samples of water supply: p=0.09 |

| Boer et al.27 | - History of travel: p<0.001- Living with gastrointestinal symptoms: p<0.001- Use of antacids: p<0.001- Antibiotic use: p<0.001 |

| Menéndez et al.16 | - Contact with children≤14 años: p=0.014; OR 2.529 [1.198–5.339]- E. vermicularis coinfection: p<0.001; OR 71.667 [4.217–1218.052]- E. vermicularis in household contacts: p=0.006; OR 2.836 [1.327–6.060] |

Contact with children has been identified by several authors as an important risk factor for infection. Engsbro et al.26 conducted a study in 143 patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome, identifying D. fragilis as the most frequent intestinal protozoan (prevalence 35%), and demonstrating the presence of children aged 5–18 years as the main risk factor for D. fragilis infection in adults (p<0.0001, OR 2.29 [1.49–3.51]).

Regarding travel history,26–29 Norberg et al.23 find that 63% of patients diagnosed with D. fragilis infection had a history of travel to Africa, South America and the Middle East. Stark et al.28 studied sixty patients infected with D. fragilis and found that six (10%) had a history of recent foreign travel. These same authors postulated that D. fragilis infection is one of the causes of traveller's diarrhoea, describing seven cases of patients with diarrhoea and a history of travel.29 A recent study30 finds 18.7% of D. fragiis infections in travellers with prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms. However, as the exact incubation period of the disease is not known, the possible influence of travel, as well as many of the epidemiological data related to the seasonality of infection, should be treated with caution.

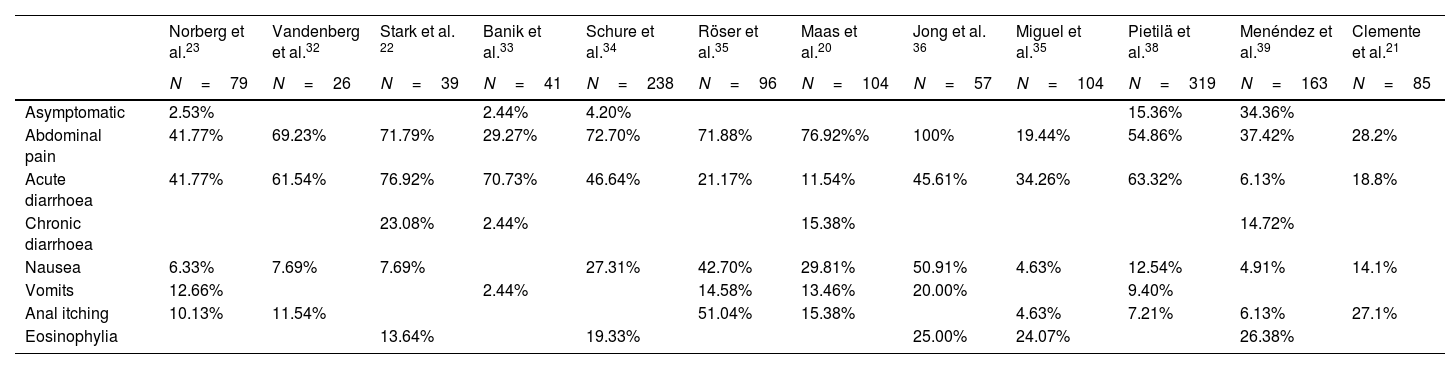

Pathogenicity and clinical symptomatologyThe role of D. fragilis in causing gastrointestinal pathology is controversial, although the available scientific evidence links it to multiple symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhoea (Table 3). However, a recent retrospective study31 analysed 27,918 patients tested by stool PCR of whom 6215 (22.3%) were positive for D. fragilis and found that the incidence of symptoms before the test was similar in those positive for Dientamoeba and those with all-negative PCR.

Comparative table of the frequency of symptoms in patients with Dientamoeba fragilis infection as reflected in some of the published studies.

| Norberg et al.23 | Vandenberg et al.32 | Stark et al. 22 | Banik et al.33 | Schure et al.34 | Röser et al.35 | Maas et al.20 | Jong et al. 36 | Miguel et al.35 | Pietilä et al.38 | Menéndez et al.39 | Clemente et al.21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=79 | N=26 | N=39 | N=41 | N=238 | N=96 | N=104 | N=57 | N=104 | N=319 | N=163 | N=85 | |

| Asymptomatic | 2.53% | 2.44% | 4.20% | 15.36% | 34.36% | |||||||

| Abdominal pain | 41.77% | 69.23% | 71.79% | 29.27% | 72.70% | 71.88% | 76.92%% | 100% | 19.44% | 54.86% | 37.42% | 28.2% |

| Acute diarrhoea | 41.77% | 61.54% | 76.92% | 70.73% | 46.64% | 21.17% | 11.54% | 45.61% | 34.26% | 63.32% | 6.13% | 18.8% |

| Chronic diarrhoea | 23.08% | 2.44% | 15.38% | 14.72% | ||||||||

| Nausea | 6.33% | 7.69% | 7.69% | 27.31% | 42.70% | 29.81% | 50.91% | 4.63% | 12.54% | 4.91% | 14.1% | |

| Vomits | 12.66% | 2.44% | 14.58% | 13.46% | 20.00% | 9.40% | ||||||

| Anal itching | 10.13% | 11.54% | 51.04% | 15.38% | 4.63% | 7.21% | 6.13% | 27.1% | ||||

| Eosinophylia | 13.64% | 19.33% | 25.00% | 24.07% | 26.38% |

Despite these findings multiple studies describe clinical symptomatology attributable to D. fragilis infection17,18,22–26,29–32,34–41 with a highly variable duration, ranging from days to two years.25 Gastrointestinal symptoms are described in most studies and include: abdominal pain of varying intensity and duration with a frequency ranging from 19.44% to 100%15,16,20–24,27–30,32–39 acute or chronic diarrhoea with a frequency ranging from 21.17% to 100%15,16,20–24,27–30,32–39 sometimes with the presence of leukocytes,23,27,31,38 and less frequently nausea and vomiting.25,26,36,38 The presence of diarrhoea has been more frequently associated with acute infection and the presence of abdominal pain with chronic infection.38 In the case of diarrhoea, a meta-analysis42 including 47 studies has recently been published. Seven of these described 22% of D. fragilis in faeces of which only 23% had diarrhoea, in another eleven studies, 4.3% of patients had D. fragilis, of which 54% had diarrhoea. Twelve other studies described D. fragilis in 1.6% of individuals with diarrhoea and in 9.6% of diarrhoeal stools. Five studies analysed the prevalence of D. fragilis in individuals with and without diarrhoea; the two with a statistically significant difference between groups had discordant results. The only cohort study with an adequate control group reported diarrhoea in a higher proportion of children with D. fragilis than in controls. The authors conclude that the evidence that D. fragilis would cause diarrhoea is inconclusive.

Some authors have analysed the presence of calprotectin in Dientamoeba-positive patients to try to establish its pathogenicity, also with contradictory results. Brands et al.40 compared two hundred stool samples from children aged 5–19 years with chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea with 122 samples from a healthy children of the same age. They detected D. fragilis in 45% of patients and in 71% of healthy children without differences between the median concentrations of calprotectin in patients and healthy children with a positive and those with a negative PCR result (40 (40–55)μg/g vs 40 (40–75)μg/g, respectively). For this reseason they recommended avoid the routinely testing for D. fragilis in children with chronic abdominal pain. In contrast Aykur et al.,41 compared calprotectin levels in three groups of patients Group 1 (n=34), patients with gastrointestinal symptoms with D. fragilis without other pathogens, Group 2 (n=31), patients with gastrointestinal symptoms but negatives for D. fragilis and with other pathogenic agents and Group 3 (n=23),with healthy volunteers without any infection or gastrointestinal complaints. Calprotectin levels were significantly high in patients with both Dientamoeba and other pathogens but did not differ from each other. Given the high percentage of asymptomatic Dientamoeba patients, calprotectin could be an indicator of the need for treatment.

D. fragilis and Isospora belli are the only protozoa that have been associated with the presence of peripheral eosinophilia, with frequencies ranging from 32 to 50%.43 Regarding to the relation between D. fragilis and irritable bowel syndrome Engsbro et al.23 studied 138 patients aged 18–50 years with irritable bowel syndrome and identified the presence of D. fragilis in 35 cases at baseline and in 41% during follow-up. In another study,23 the authors treated 25 patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome and infected with D. fragilis with metronidazole or tetracycline, and observed microbiological response in 60% of patients and clinical response in 32%. Most studies suggest that up to 15% of individuals infected with D. fragilis may act as asymptomatic carriers,38,39 however, some of these patients may present with eosinophilia as the only finding.

Unlike other parasites, the relationship of D. fragilis to immunosuppression is unclear. In a study carried out at the Vall d’Hebron University Hospital by Miguel et al.,37 17 of out of 108 patients diagnosed with D. fragilis infection (15.7%) were immunocompromised: 14 by HIV, 2 by haematological malignancies and 1 patient because he was under treatment with monoclonal antibodies due to a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, without describing any difference in symptomatology or clinical course compared to immunocompetent patients.

There are few case–control studies that can shed light on the pathogenic status of Dientamoeba. Banik et al.33 compared 2 groups of patients aged 1–15 years: a case group of 41 children diagnosed with D. fragilis infection versus a control group of 41 children without D. fragilis. They described the presence of at least one symptom in 98% of infected patients, the most frequent being diarrhoea, followed by abdominal pain. Statistically significant results were only obtained for diarrhoea (p<0.002). Aykur et al.24 studied 490 patients, 59 of whom had D. fragilis in stool, and showed that diarrhoea was significantly associated with D. fragilis infection (p=0.001). A recent prospective case–control study45 of patients aged 1–17 compared 59 individuals with gastrointestinal symptoms and 47 without gastrointestinal symptoms. The authors found prevalences of 29.8% in the symptomatic group and 23.4% in the asymptomatic group with no significant differences and found no clinical or microbiological response after treatment as previously described by De Jong et al.36 However, a recent systematic review recommends testing for D. fragilis in children with persistent unexplained chronic abdominal pain and diarrhoea.46

DiagnosisSince the first description of D. fragilis, several techniques have been used to identify it. Initially, microscopy was used and various combinations of fixation fluid and stain were tested to improve diagnostic performance.1 Later, culture was studied, using different media and conditions, and proved to be a more sensitive method than the previous one.1 The real revolution in the diagnosis of D. fragilis has been experienced in recent years, thanks to the development of new techniques based on molecular biology, especially the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which has now become the test of choice or gold standard for most authors due to its high sensitivity and specificity.47

Multiple studies have compared real-time PCR with other diagnostic methods, demonstrating that PCR has superior sensitivity and specificity.47,48 Stark et al.48 describe a sensitivity and specificity of PCR close to 100%, compared to 40% and 100% respectively for culture and 34.3% and 99% respectively for conventional microscopy.

The emergence of commercial kits in recent years allowing detect simultaneously several protozoa such as: Blastocystis spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayetanensis, D. fragilis, Entamoeba complex and Giardia sp., has contributed to a better diagnosis.47–50 Autier et al.49 compared multiplex PCR with microscopy, demonstrating in the specific case of D. fragilis a diagnostic sensitivity of 97.2% versus 14.1%, with statistically significant results (p<0.001). Argy et al.50 compared several commercial multiplex PCR assay panels and found that overall sensitivity/specificity for the multiplex PCR assays was 93.2%/100% for G-DiaParaTrio, 96.5%/98.3% for Allplex® GI parasite and 89.6%/98.3% for RIDA®GENE, whereas the composite reference method presented an overall sensitivity/specificity of 59.6%/99.8%.

Calderaro et al.51 in a study published in 2018 describe the creation, for the first time to date, of a protein profile of D. fragilis by MALDI–TOF MS in order to identify specific markers for the application of this technology in the diagnosis of dientamoebiasis. They demonstrated that this diagnostic method has a sensitivity comparable to PCR, being faster, cheaper and easier to use. This study represents a breakthrough in the diagnosis of D. fragilis and lays the foundation for future commercial development for laboratory application.

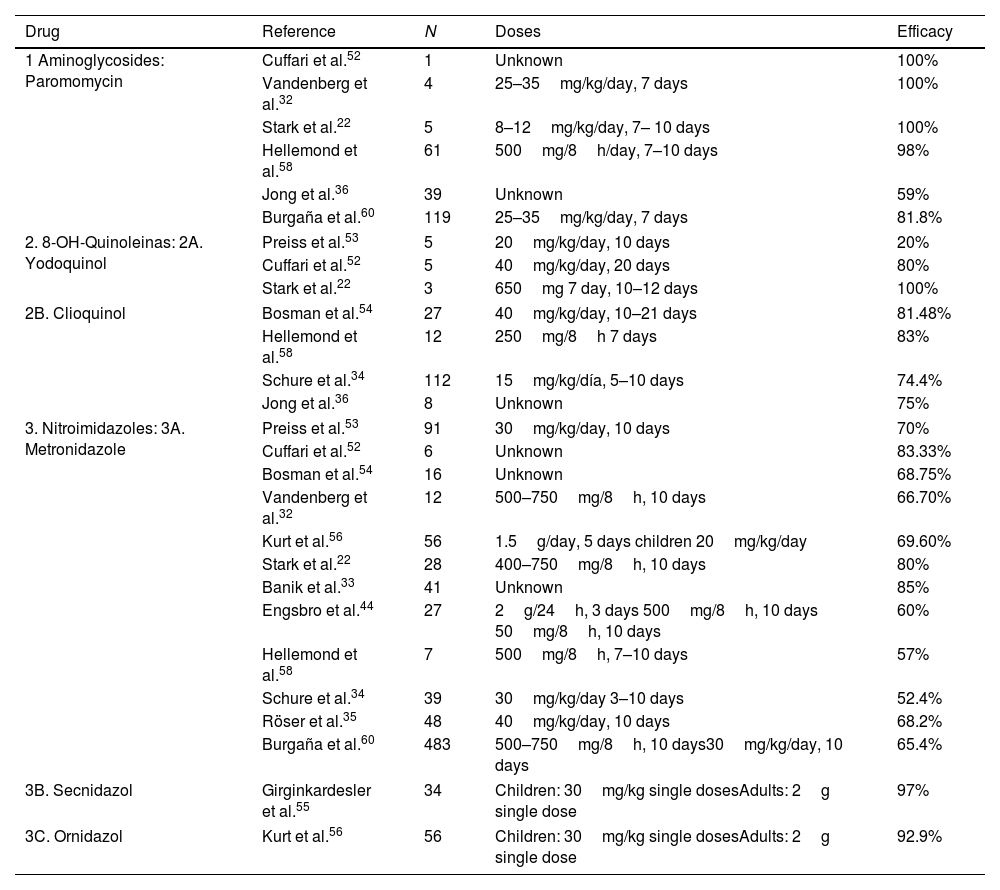

TreatmentSince the first description of D. fragilis, many studies have been carried out to evaluate the different therapeutic alternatives (Table 4). With regard to the use of metronidazole, the cure rates in the literature range from 52.4% to 85%.31,33,35,39 Only one randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial has been conducted to date to evaluate the efficacy of metronidazole.35 This study included 96 children diagnosed with D. fragilis infection, who were randomised into 2 groups, the first treated with Metronidazole and the second with placebo, describing eradication rates of 68.2% versus 11.4% at 4 weeks and only 24.9% at 8 weeks. Engsbro et al.44 compared metronidazole treatment at different doses, proposing an initial regimen of 500mg, 3 times a day for 10 days, and in case of failure a new course of metronidazole treatment, but at a higher dose. At the end of the study, they concluded that one of the causes of treatment failure with metronidazole could be an inadequate dose. At this moment the recommended dosage for treatment of D. fragilis infection with metronidazole is: 500–750mg three times a day for 10 days for adults and 35–50mgkg/day three times a day for 10 days in children.

Comparative table of the drugs used in the different studies for the treatment of D. fragilis infection.

| Drug | Reference | N | Doses | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Aminoglycosides: Paromomycin | Cuffari et al.52 | 1 | Unknown | 100% |

| Vandenberg et al.32 | 4 | 25–35mg/kg/day, 7 days | 100% | |

| Stark et al.22 | 5 | 8–12mg/kg/day, 7– 10 days | 100% | |

| Hellemond et al.58 | 61 | 500mg/8h/day, 7–10 days | 98% | |

| Jong et al.36 | 39 | Unknown | 59% | |

| Burgaña et al.60 | 119 | 25–35mg/kg/day, 7 days | 81.8% | |

| 2. 8-OH-Quinoleinas: 2A. Yodoquinol | Preiss et al.53 | 5 | 20mg/kg/day, 10 days | 20% |

| Cuffari et al.52 | 5 | 40mg/kg/day, 20 days | 80% | |

| Stark et al.22 | 3 | 650mg 7 day, 10–12 days | 100% | |

| 2B. Clioquinol | Bosman et al.54 | 27 | 40mg/kg/day, 10–21 days | 81.48% |

| Hellemond et al.58 | 12 | 250mg/8h 7 days | 83% | |

| Schure et al.34 | 112 | 15mg/kg/día, 5–10 days | 74.4% | |

| Jong et al.36 | 8 | Unknown | 75% | |

| 3. Nitroimidazoles: 3A. Metronidazole | Preiss et al.53 | 91 | 30mg/kg/day, 10 days | 70% |

| Cuffari et al.52 | 6 | Unknown | 83.33% | |

| Bosman et al.54 | 16 | Unknown | 68.75% | |

| Vandenberg et al.32 | 12 | 500–750mg/8h, 10 days | 66.70% | |

| Kurt et al.56 | 56 | 1.5g/day, 5 days children 20mg/kg/day | 69.60% | |

| Stark et al.22 | 28 | 400–750mg/8h, 10 days | 80% | |

| Banik et al.33 | 41 | Unknown | 85% | |

| Engsbro et al.44 | 27 | 2g/24h, 3 days 500mg/8h, 10 days 50mg/8h, 10 days | 60% | |

| Hellemond et al.58 | 7 | 500mg/8h, 7–10 days | 57% | |

| Schure et al.34 | 39 | 30mg/kg/day 3–10 days | 52.4% | |

| Röser et al.35 | 48 | 40mg/kg/day, 10 days | 68.2% | |

| Burgaña et al.60 | 483 | 500–750mg/8h, 10 days30mg/kg/day, 10 days | 65.4% | |

| 3B. Secnidazol | Girginkardesler et al.55 | 34 | Children: 30mg/kg single dosesAdults: 2g single dose | 97% |

| 3C. Ornidazol | Kurt et al.56 | 56 | Children: 30mg/kg single dosesAdults: 2g single dose | 92.9% |

Iodoquinol has been used in the treatment of D. fragilis infection mainly in the USA. It is administered orally at a dose of 650mg three times a day for 20 days in adults, and 40mg/kg/day in three doses (maximum 2g) for 20 days in children. Cure rates range from 20 to 100%, although all studies with this drug include a small number of patients.52,53 Cuffari et al.52 used Iodoquinol to treat 5 patients, achieving cure in 4 of them. However, Preiss et al.53 used this drug in 5 patients, documenting cure in only 1 of them, although they used lower doses and for less time than the previous ones. Clioquinol is similar to iodoquinol, although with somewhat higher cure rates ranging from 74.4% to 83%.34,54

Secnidazole and Ornidazole (Table 4) are the newer 5-nitroimidazole derivatives. Their main feature is that they have a longer half-life than metronidazole, so they are administered only once daily, thereby decreasing the incidence of adverse effects. Girginkardesler et al.55 studied secnidazole treatment in 35 patients with D. fragilis, and 34 (97%) were cured. Kurt et al.56 conducted a study comparing treatment with Ornidazole versus Metronidazole in 112 patients who were randomised into 2 groups. The first group received treatment with Ornidazole as a single daily dose and the second group received treatment with Metronidazole 3 times daily, both orally. In this study, parasitological cure was achieved in 52 of the 56 patients treated with Ornidazole (92.9%), compared to 39 of the patients treated with Metronidazole (69.6%). The 4 patients who failed treatment with Ornidazole were re-treated with Ornidazole and finally cured. Of the second group, only 8 out of 17 patients were cured with a second course of Metronidazole treatment, so the remaining 9 patients were treated with Ornidazole and eradication of the infection was achieved.

Clioquinol, iodoquinol, secnidazol and ornidazol are available in Spain only through the foreign medicines service.

Regarding tetracyclines, Preiss et al.53 used oxytetracycline in 8 children and doxycycline in 4 children with known D. fragilis infections, achieving cure rates of 90% and 75% respectively.

Nagara et al.57 evaluate the susceptibility of D. fragilis to several commonly used antiparasitic agents: diloxanide furoate, furazolidone, iodoquinol, metronidazole, nitazoxanide, ornidazole, paromomycin, secnidazole, ronidazole, tetracycline, and tinidazole. Minimum lethal concentrations (MLCs) were as follows: ornidazole, 8–16μg/ml; ronidazole, 8–16μg/ml; tinidazole, 31μg/ml; metronidazole, 31μg/ml; secnidazole, 31–63μg/ml; nitazoxanide, 63μg/ml; tetracycline, 250μg/ml; furazolidone, 250–500μg/ml; iodoquinol, 500μg/ml; paromomycin, 500μg/ml; and diloxanide furoate, >500μg/ml. They concluded that 5-nitroimidazole derivatives to be the most active compounds in vitro against D. fragilis.

However most studies agree on the superiority of paramomycin over metronidazole, with most authors considering it the treatment of choice.58–60 Pietila et al. studied59 369 patients and paromomycin (n=297) showed a clearance rate of 83% againts 42% in the metronidazol group (n=84), (aOR 18.08 [7.24–45.16], p<0.001). For metronidazole the rate was 42% (n=84), 37% for secnidazole (n=79), and 22% for doxycycline (n=32). In pairwise comparisons, paromomycin outdid the three other regimens (p<0.001).

In the study by Miguel et al.,37 in Spain, only 29 out of 108 patients were treated, 25 of whom received metronidazole, 3 paromomycin and 1 iodoquinol. Of these patients, only 14 underwent a control coproparasitic study, and 85.71% of them were found to have eradicated D. fragilis (without specifying the percentage of cure with each of the drugs used). The other study carried out in Spain is the one published by Burgaña et al.60 about 586 patients with cure rates of 81.8% with paromomycin versus 65.4% with metronidazole, with a statistically significant difference between the two drugs (p=0.007). Clemente et al.21 studied 85 patients and found that paromomycin showed a 100% of cure rate versus 53.3% in the metronidazole group.

On the other hand, some cases of spontaneous cure have been described in the literature, although on rare occasions, such as the study carried out by Van Hellemond et al.58 These authors describe spontaneous eradication of D. fragilis in up to 41% of individuals. Banik et al.33 describe spontaneous eradication of D. fragilis in 3 out of 48 patients belonging to the placebo group of the above-mentioned clinical trial.

ConclusionsD. fragilis has emerged as one of the most prevalent protozoa in our environment yet doubts remain about its epidemiology or pathogenicity. Although the relationship with E. vermicularis seems clear, the definitive role of E. vermicularis in its transmission remains to be clarified, as does the possibility that it is a zoonosis. This point is particularly interesting given the practically non-existent prevalence in companion animals, so it is possible that we are dealing with a reverse zoonosis. With regard to diagnosis, this has been the greatest advance in our knowledge of Dientamoeba since it was first described. Currently, all authors agree on polymerase chain reaction as the technique of choice, favoured by the development of commercial multiplex diagnostic kits.

Despite contradictory data on its pathogenicity, there seems to be a relationship between its presence and the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, especially in the form of abdominal pain and/or diarrhoea, supported by multiple descriptive studies, although the results of the few cohort studies carried out are again contradictory. In relation to treatment, the results support the superiority of paramomycin over other options, with possibly metronidazole as a second alternative in our setting.

In conclusion the presence of D. fragilis should be considered in patients with both acute and chronic gastrointestinal pathology, it should be ruled out by polymerase chain reaction and in case of presence of symptoms its treatment of choice would be paramomycin.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsDr. Boga reports grants from Seegene Company, and non-financial support to Congress Attendance from Werfen Company (Seegene Company distribution in Spain) outside the submitted work.

Dr. García-Pérez reports non-financial support from, MSD, Pfizer, Gilead, Boehringer Ingelheim, and, Esteve to Congress Attendance outside the submitted work.

Dr. Rodriguez-Perez reports non-financial support from DiaSorin Company to Congress Attendance Support outside the submitted work.

Dr. Rodriguez-Guardado reports grants from MSD and non-financial support from Pzifer, MSD, Gilead and Angelini to Congress Attendance Support outside the submitted work.

The rest of authors have nothing to disclose.