Bartonella bacilliformis can cause a potentially fatal infection, Carrion's disease. This review synthesized data on the prevalence of this bacterial infection in South American countries. A comprehensive literature search relevant articles (published between 2010 and 2022) was conducted in four databases. Full texts were selected based on PECOTS eligibility and JBI methodological quality. The pooled bacterial infection rate was calculated using a random-effects meta-analysis model. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were used to investigate statistical heterogeneity. Five studies (covering 717 individuals from Peru and Ecuador) were eligible for meta-analysis. The percentage of seropositive IgG antibodies against B. bacilliformis was 28.21% (95% CI: 6.29–33.39) among healthy Ecuadorian children. In Peru, the pooled bacterial detection rate in symptomatic individuals was 15.60% (95% CI: 4.24–31.98), using molecular tests. Carrion's disease is endemic in the Andean valleys, but a gradual reduction in infection rates among acute febrile patients in Peru has been observed in recent years. Laboratory diagnosis of this infection continues to be neglected in other South American countries. Public managers must plan effective arrangements in primary care services, integrating various technological levels to ensure comprehensive health care.

Bartonella bacilliformis puede causar una infección potencialmente fatal, la enfermedad de Carrión. Esta revisión sintetizó datos sobre la prevalencia de esta infección bacteriana en países de América del Sur. Se realizó una búsqueda exhaustiva de literatura relevante (publicada entre 2010 y 2022) en cuatro bases de datos. Los textos completos se seleccionaron en función de la elegibilidad PECOTS y la calidad metodológica JBI. La tasa de infección bacteriana agrupada se calculó utilizando un modelo de metaanálisis de efectos aleatorios. Se utilizaron análisis de subgrupos y metarregresión para investigar la heterogeneidad estadística. Cinco estudios (que cubren a 717 individuos de Perú y Ecuador) fueron elegibles para el metaanálisis. El porcentaje de anticuerpos IgG seropositivos contra B. bacilliformis fue del 28,21% (IC 95%: 6,29-33,39) entre niños ecuatorianos sanos. En Perú, la tasa de detección bacteriana agrupada en individuos sintomáticos fue del 15,60% (IC 95%: 4,24-31,98), utilizando pruebas moleculares. La enfermedad de Carrión es endémica en los valles andinos, pero en los últimos años se ha observado una reducción gradual en las tasas de infección entre los pacientes con fiebre aguda en Perú. El diagnóstico de laboratorio de esta infección sigue siendo descuidado en otros países de América del Sur. Los gestores públicos deben planificar arreglos efectivos en los servicios de atención primaria, integrando varios niveles tecnológicos para garantizar una atención sanitaria integral.

Carrion's disease is an infectious tropical disease caused by Bartonella bacilliformis. Sandflies of the genus Lutzomya are the most important vectors for the transmission of this bacterium, mainly the straw mosquito (Lutzomya verrucarum) in South America.1 When B. bacilliformis is inoculated into humans through the bite of hematophagous Lutzomya, it infects erythrocytes and endothelial cells. After the incubation period (20–60 days), the infection may become asymptomatic or manifest as Carrion's disease. Clinical recovery does not necessarily result in bacterial clearance. Asymptomatic carriers constitute the only reservoir capable of transmitting this bacterial species to new sandflies, becoming decisive for the maintenance of the zoonotic cycle and being able to introduce it into new areas.2–4

The acute phase of the disease presents symptoms such as fever, chills, myalgia, arthralgia, and a severe headache, the development of severe hemolytic anemia, jaundice, and liver impairment. Clinically characterized as Oroya fever, these symptoms affect more children. Complications or secondary opportunistic infections resulting from bacteremia tend to worsen the clinical picture and lead to high mortality rates (up to 88%) if antimicrobial therapy is not administered.1 The chronic phase is characterized by abnormal vasculoendothelial proliferations resulting in multiple angioproliferative skin lesions (called “Peruvian warts”), especially on the face and upper and lower extremities. Erythematous nodules resemble hemangiomas and can suppurate or generate scars in the patient, persisting for months or years.2,3,5

Carrion's disease occurs exclusively in some South American countries due to the circulation of B. bacilliformis, which predominates in the western portion of the Andes Mountains. Bacterial exposure is more frequent in the mountainous regions of Peru, but there have also been records in Chile, Guatemala, and Bolivia.2,6 However, in recent decades, there have been several occurrences in previously uncommon regions, such as Ecuador, Colombia, and other regions in Peru such as Antioquia, Caldas, Huila, La Guajira and Risaralda.3,5,7

In recent decades, significant climate changes, associated with human migrations, may lead to a greater risk of the propagation of vectors and territorial expansion of this bacterium in the South American region.1,5 Therefore, a regionalized view of the occurrences of B. bacilliformis infection would allow us to better understand the spatio-temporal dynamics of this neglected health problem. Thus, the objective of this review was to synthesize data on the prevalence of Carrion's disease in this American region, carrying out comprehensive research and meta-analysis.

MethodologySources of information and search strategyThe preferred reporting elements for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) served as the basis for conducting the protocol established for this systematic review as registered on the PROSPERO website (CRD42021262458) (available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021262458). The Regional Virtual Health Library portal, EmBase, PubMed, SciELO, and other international databases were accessed until November 2023 in search of relevant articles. Regardless of language. MeSH phrases and keywords such as “human infection”, “Bartonella and Bartonellosis”, “prevalence and frequency” and “country name” were entered into the search field of each database. The search strategy used for four databases is given in supplementary material.

Study selectionAfter listing all articles found in the databases, duplicates were removed. The remaining articles underwent a rigorous selection carried out by two independent reviewers, and a third reviewer was available to arbitrate on likely disagreements. Study abstracts were screened for eligibility criteria. After reading the full text, eligible studies were judged regarding their content and methodological quality for inclusion in the review and meta-analysis.

The eligibility criteria included studies involving human beings of any age, sex, or race, residing in South American countries who underwent a laboratory diagnosis for B. bacilliformis infection. The study must be original, whether observational, cross-sectional, case–control, or cohort, and have a record of publication between the years 2010 and 2022.

An internationally validated checklist was used to carefully assess the quality of the articles. It includes aspects such as study design, sampling adequacy, determination of collection methods and measurement tools, analysis and presentation of data, and identification of confounding factors.8 It was defined that each item would be scored 0 or 1, if the answers were “No or Not clear” and “Yes”, respectively. The sum of the scores could vary from 0 to 10, being considered studies of low quality (obtaining ≤4 points), moderate (5–7), and high (>8); the better the quality, the lower the risk of methodological bias in the study. The methodological quality score is inversely proportional to the study's risk of bias. Exclusion criteria were duplicate articles, full text not available, ineligible studies, or studies with low methodological quality.

Data extraction and statistical analysisTwo reviewers compiled data from the articles included in the review into an electronic spreadsheet. Subsequently, they were compared by a third party and, if necessary, extracted again. The following data were extracted: title, authors, and year of publication; study design, country, and sample size; period of data collection and types of population; number of infections diagnosed and diagnostic method; in addition to other information.

The “metaprop” and “meta” commands of Stata™ software v11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) were used for meta-analysis. B. bacilliformis infection rates (per study and grouped, as well as their respective 95% confidence intervals) were calculated through the use of Freeman-Tukey transformation in the random effect model. The chi-square test was employed to examine potential of heterogeneity between studies, a p-value of less than 0.05 was deemed significant. The percentage of variation in the infection rate was assessed using the I2 statistic; a value of more than 50% is regarded as high.

Weighted regression and a visual examination of the funnel plot were used to evaluate publication bias. Subgroup analyses were used to look into potential sources of variation in infection rates, and univariate regression was used to determine the effects of those sources. The level of statistical significance was considered 5%.

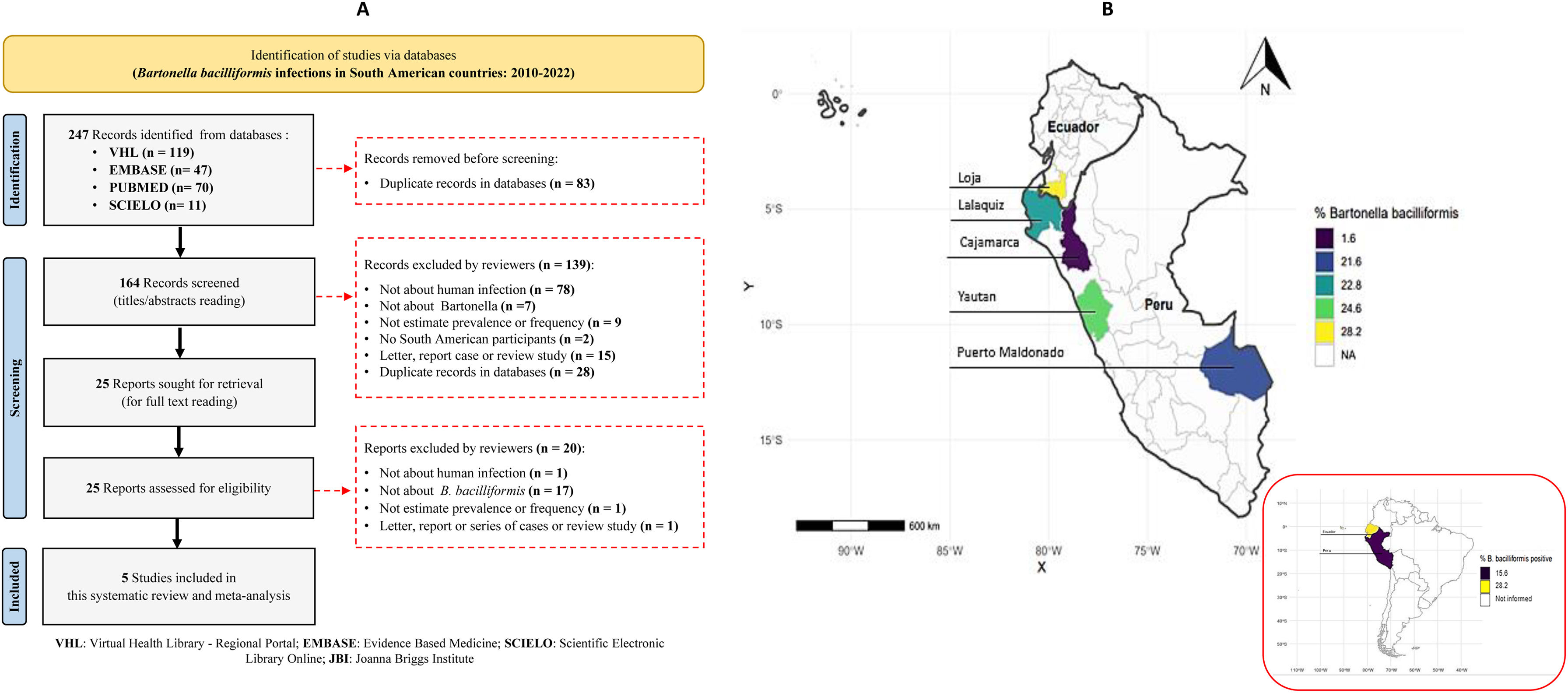

ResultsResults of literary research and study selectionAfter completing the searches addressing B. bacilliformis infections in South America, 247 citations were identified in the four databases searched. In total, 242 articles were excluded, either due to duplication or after assessments of eligibility and risk of study bias requirements, leaving only five eligible articles included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.7,9–12Fig. 1 shows the sequence of steps included in the process of selecting articles, with details about exclusions.

Recurrent flaws were observed in relation to the sampling of participants in most studies, such as: non-representation of the target population, inadequate recruitment, and a lack of sample calculation. These characteristics suggest a potential risk of selection bias, which could, in part, explain the high variation between bacterial infection rates by study. The studies included obtained between 7 and 9 points, resulting in an average of 8.2, considered to be of high methodological quality.

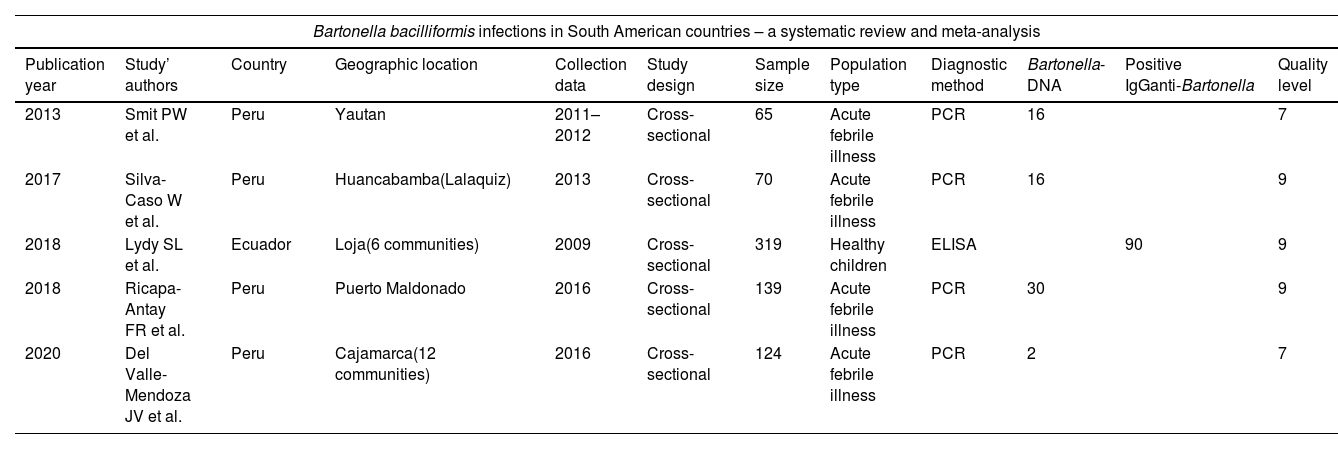

The five studies (published between 2013 and 2020) addressing B. bacilliformis preferred a cross-sectional design. They covered data collected between 2009 and 2016 from five different locations in Peru and Ecuador. In total, these studies involved 717 participants, 398 were Peruvians (55.5%), of both sexes, including children and adults. The most relevant data from the studies included in this meta-analysis are described in Table 1.

Main data extracted from studies addressing Carrion's disease in South America (publication 2010–2022).

| Bartonella bacilliformis infections in South American countries – a systematic review and meta-analysis | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | Study’ authors | Country | Geographic location | Collection data | Study design | Sample size | Population type | Diagnostic method | Bartonella-DNA | Positive IgGanti-Bartonella | Quality level |

| 2013 | Smit PW et al. | Peru | Yautan | 2011–2012 | Cross-sectional | 65 | Acute febrile illness | PCR | 16 | 7 | |

| 2017 | Silva-Caso W et al. | Peru | Huancabamba(Lalaquiz) | 2013 | Cross-sectional | 70 | Acute febrile illness | PCR | 16 | 9 | |

| 2018 | Lydy SL et al. | Ecuador | Loja(6 communities) | 2009 | Cross-sectional | 319 | Healthy children | ELISA | 90 | 9 | |

| 2018 | Ricapa-Antay FR et al. | Peru | Puerto Maldonado | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 139 | Acute febrile illness | PCR | 30 | 9 | |

| 2020 | Del Valle-Mendoza JV et al. | Peru | Cajamarca(12 communities) | 2016 | Cross-sectional | 124 | Acute febrile illness | PCR | 2 | 7 | |

DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; ELISA: enzyme linked immune sorbent assay; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

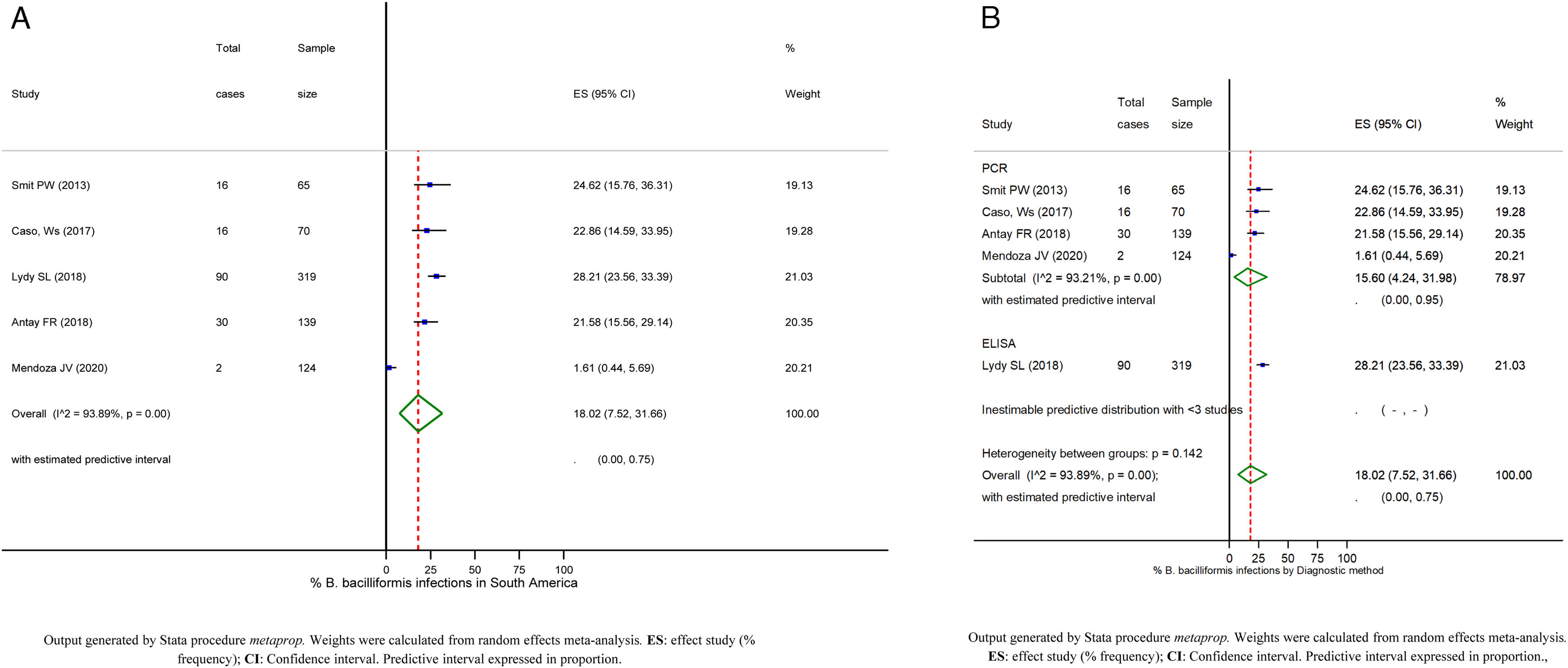

The bacterial infection rate grouping these two countries was 18.02% (95% CI: 7.52–31.66%), with a predictive range of 0.00–75.00%, as can be seen in the forest graph in Fig. 2A. The individual rates varied between 1.61 and 24.62%; using the Q-test (p-value <0.01) and the I2 statistic (93.89%) confirmed the high heterogeneity between the studies. In Ecuador, positivity for IgG antibodies against B. bacilliformis diagnosed by ELISA (enzyme linked immune sorbent assay) was 28.21% (95% CI: 6.29–33.39) among supposedly healthy children. While in Peru, the pooled rate of infections was estimated at 15.60% (95% CI: 4.24–31.98) by performing molecular diagnosis by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) in patients with acute febrile illness (Fig. 2B).

Forest plot of pooled Bartonella bacilliformis infections in South American countries: (A) by all confirmed cases and (B) by diagnostic method. B. bacilliformis infection rate estimated in each study is indicated by a blue square. The size of the symbols is proportional to the contribution weight of each study in meta-analysis. Black horizontal lines represent the confidence interval. The bacterial infection rate grouping the five studies is shown by the green diamond. The vertical dotted line in red indicates the distancing of individual rates from the grouped estimate.

Analysis of the funnel plot (Begg's test) showed an asymmetry for the selected studies, indicating the likelihood of publication bias. The presence of bias was confirmed by the Egger test (β coefficient: 0.330, p=0.151). Possible sources of bias were assessed against the stability of individual rates of bacterial infection in humans. However, the result of the sensitivity analysis demonstrated that no specific study had a significant influence in relation to the grouped rate of studies carried out in South American countries.

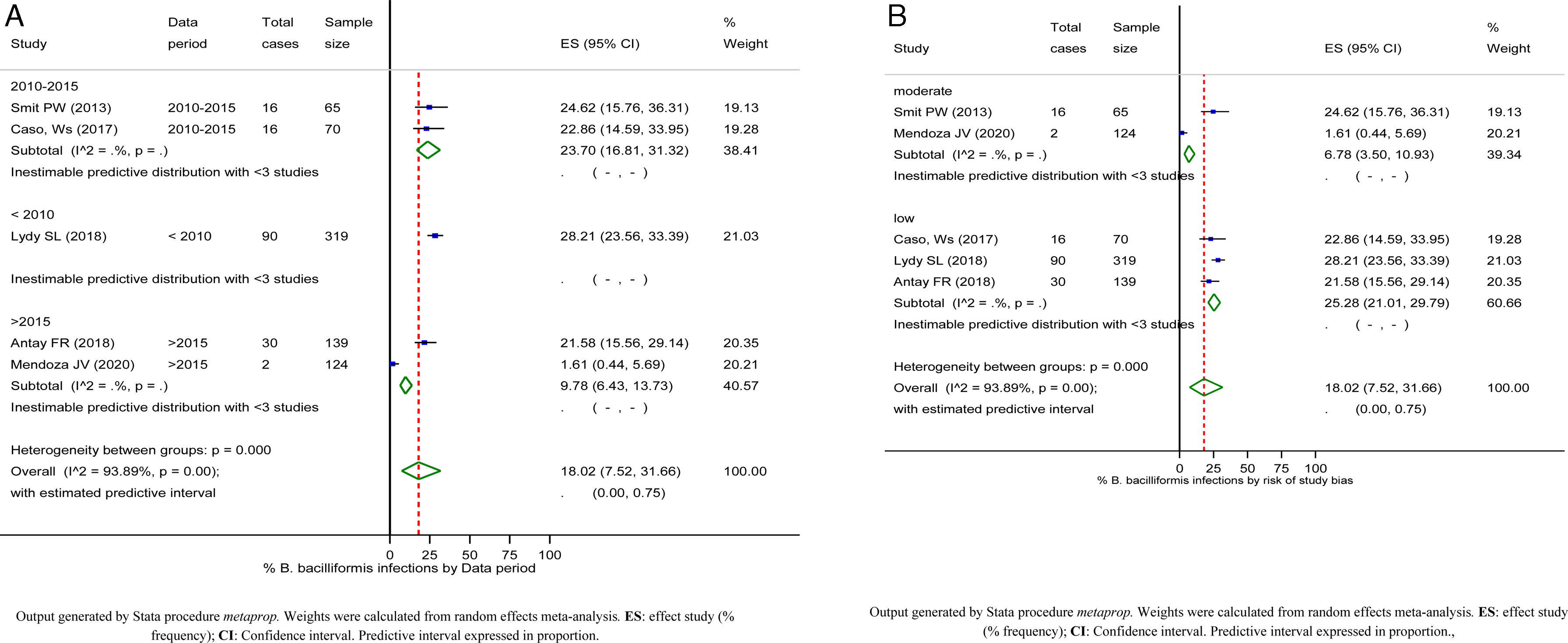

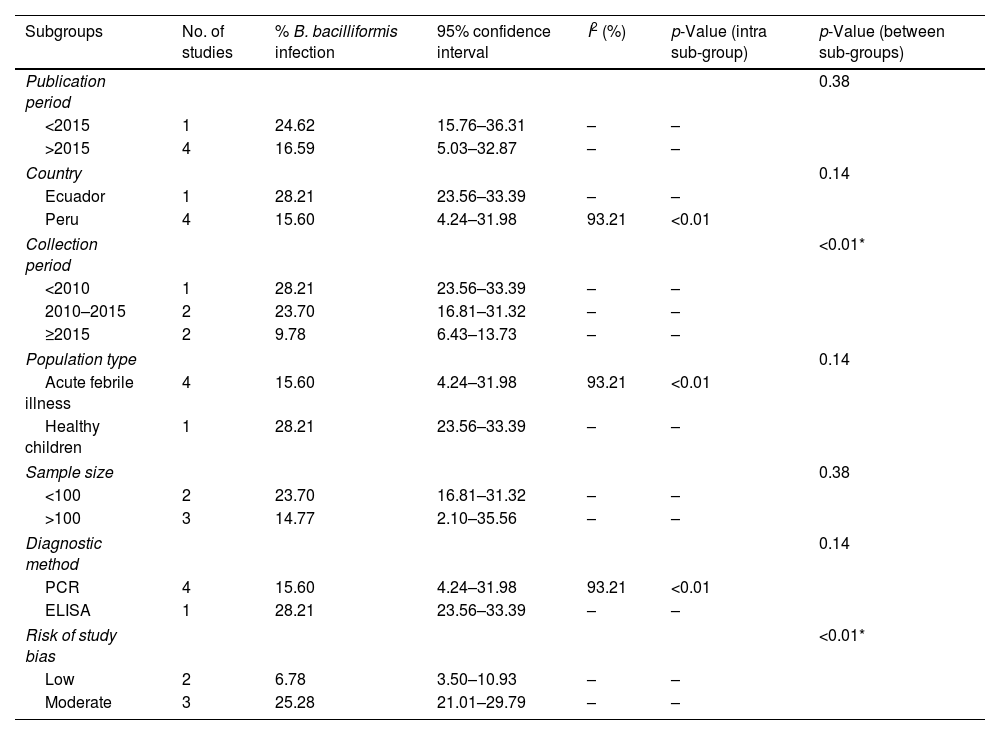

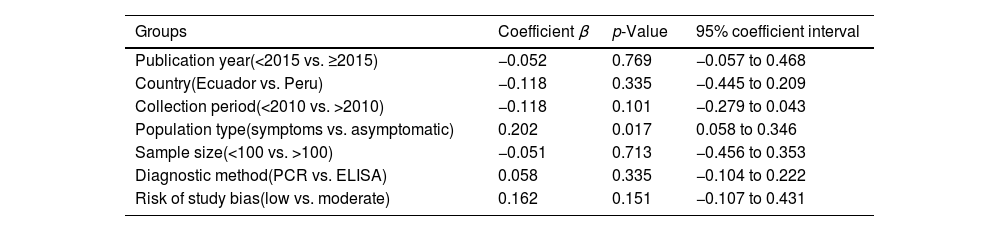

Subgroup analyses showed the existence of a significant difference between the grouped rates of B. bacilliformis infection, stratified by data collection period and risk of study bias (Table 2). The highest rates of bacterial infection were reported with data collected before 2010 and in studies with high methodological quality (Fig. 3). However, the results of univariate meta-regressions show the absence of significant effects of the possible factors studied in association with the pooled estimates of bacterial infection (Table 3).

Subgroup analyses regarding Bartonella bacilliformis infections in South America.

| Subgroups | No. of studies | % B. bacilliformis infection | 95% confidence interval | I2 (%) | p-Value (intra sub-group) | p-Value (between sub-groups) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Publication period | 0.38 | |||||

| <2015 | 1 | 24.62 | 15.76–36.31 | – | – | |

| >2015 | 4 | 16.59 | 5.03–32.87 | – | – | |

| Country | 0.14 | |||||

| Ecuador | 1 | 28.21 | 23.56–33.39 | – | – | |

| Peru | 4 | 15.60 | 4.24–31.98 | 93.21 | <0.01 | |

| Collection period | <0.01* | |||||

| <2010 | 1 | 28.21 | 23.56–33.39 | – | – | |

| 2010–2015 | 2 | 23.70 | 16.81–31.32 | – | – | |

| ≥2015 | 2 | 9.78 | 6.43–13.73 | – | – | |

| Population type | 0.14 | |||||

| Acute febrile illness | 4 | 15.60 | 4.24–31.98 | 93.21 | <0.01 | |

| Healthy children | 1 | 28.21 | 23.56–33.39 | – | – | |

| Sample size | 0.38 | |||||

| <100 | 2 | 23.70 | 16.81–31.32 | – | – | |

| >100 | 3 | 14.77 | 2.10–35.56 | – | – | |

| Diagnostic method | 0.14 | |||||

| PCR | 4 | 15.60 | 4.24–31.98 | 93.21 | <0.01 | |

| ELISA | 1 | 28.21 | 23.56–33.39 | – | – | |

| Risk of study bias | <0.01* | |||||

| Low | 2 | 6.78 | 3.50–10.93 | – | – | |

| Moderate | 3 | 25.28 | 21.01–29.79 | – | – | |

Output generated by Stata™ procedure metaprop. Weights are from random effects meta-analysis. ELISA: enzyme linked immune sorbent assay; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Forest plot of pooled Bartonella bacilliformis infections in South America: (A) by data collection period and (B) by risk of study bias. B. bacilliformis infection rate estimated in each study is indicated by a blue square. The size of the symbols is proportional to the contribution weight of each study in meta-analysis. Black horizontal lines represent the confidence interval. The bacterial infection rate grouping the five studies is shown by the green diamond. The vertical dotted line in red indicates the distancing of individual rates from the grouped estimate.

Summary of univariate meta-regression analyses associated with Bartonella bacilliformis infection in South American (publications 2010–2022).

| Groups | Coefficient β | p-Value | 95% coefficient interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year(<2015 vs. ≥2015) | −0.052 | 0.769 | −0.057 to 0.468 |

| Country(Ecuador vs. Peru) | −0.118 | 0.335 | −0.445 to 0.209 |

| Collection period(<2010 vs. >2010) | −0.118 | 0.101 | −0.279 to 0.043 |

| Population type(symptoms vs. asymptomatic) | 0.202 | 0.017 | 0.058 to 0.346 |

| Sample size(<100 vs. >100) | −0.051 | 0.713 | −0.456 to 0.353 |

| Diagnostic method(PCR vs. ELISA) | 0.058 | 0.335 | −0.104 to 0.222 |

| Risk of study bias(low vs. moderate) | 0.162 | 0.151 | −0.107 to 0.431 |

Output generated by Stata™ procedure metaprop. Weights are from random effects meta-analysis. ELISA: enzyme linked immune sorbent assay; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

p-Value ≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

This systematic review provides an updated view on the presence of B. bacilliformis infection in South American countries over the last 12 years. Despite the high morbidity and mortality resulting from bacterial infection, the lack of interest from the scientific community in diagnosing this disease was evident. This is due to the small number of articles found in international databases. B. bacilliformis infections are continually ignored and underestimated in the Americas. However, they affect the health of native populations and can affect travelers (whether sporadic workers or tourists) who transit through the Andean region.2,4 Except for the four studies conducted in Peru between 2011 and 2016, where Carrion's disease is considered a significant health issue. We found only one study from 2009 involving a population in Ecuador. This highlights the lack of epidemiological information in other South American countries. Additionally, the outdated data corroborate previous studies.2,4,6

According to the present meta-analysis, the infection rate by B. bacilliformis was approximately 18%, grouping both countries, Peru and Ecuador. Regarding the results of subgroup analyses, higher rates of bacterial infection were reported for studies with high methodological quality compared to those classified with moderate. In addition to this factor, data collected in the period prior to 2010 was significantly higher than data obtained in the last 5 years (28.21% vs. 9.78%). The current review shows that Carrion's disease remains an unresolved challenge in low- and middle-income countries. One plausible justification for the perpetuation of the disease in this region is that B. bacilliformis circulates freely in remote and mountainous areas. These areas shelter small rural communities, extremely poor far from health establishments with the technical and human resources for adequate diagnosis.4,6

Previous studies have described Carrion's disease as endemic in mountainous regions of Peru. The persistence of this species of bacteria was initially geographically restricted to the Andes Mountains. It was associated with environmental and ecological characteristics, in addition to human socioeconomic factors, which favor the proliferation of the vector L. verrucarum. However, their sporadic occurrences have also been reported in provinces that were previously undetected. Thet suggest an expansion in the distribution of B. bacilliformis to lowland and jungle regions, resulting from climate change.2,11,13 It is important to note that this health problem is not restricted to the Andean countries. In addition, in the last two decades, specific cases have occurred in neighboring South American countries, affecting foreign travelers who were traveling to endemic areas for work reasons. Currently, many people from Peru, Ecuador and Colombia are migrating to other countries due to the economic crisis that is affecting these countries recognized as endemic.14

However, we believe that not all cases are registered or even diagnosed, and, therefore, these numbers are probably underestimated. Therefore, the proposition of laboratory detection is a dilemma because many doctors do not consider the possibility of this bacterial infection occurring. Furthermore, in cases of clinical suspicion of Carrion's disease, there are still technical and laboratory difficulties for a conclusive diagnosis.5 These hypotheses are motivated by national data, particularly considering endemic countries. In 2015, the National Department of Epidemiology of the Ministry of Health reported incidences of 0.22 and 0.12 per 100,000 inhabitants for Oroya fever and Peruvian warts, respectively. On the other hand, Carrion's disease is not considered a notifiable disease by the Ministry of Health of Ecuador.14 The discrepancy between the number of cases reported in observational studies and official government bulletins is attributed in terms of populational group and design.

More sensitive immunological or molecular methods are only carried out in reference centers or used in scientific research. In endemic areas, the most common method to confirm acute bacterial infection is the Giemsa-stained blood smear. However, this method has low sensitivity (30%) and requires highly trained personnel.4 As opposed to laboratory practice, more recent studies have chosen to use the PCR technique to diagnose B. bacilliformis in the acute phase of the disease.6 The syndrome known as acute febrile illness, common in the Southern Hemisphere, is generally associated with different etiologies.11,15 Although molecular techniques may have sensitivity and specificity greater than 93%, they have shown limited value for asymptomatic carriers of this bacterial species. This is due to the lack of standardization of the specific gene fragment and amplification technique.16

In Peru, the pooled rate of B. bacilliformis infections was estimated at 15.60% through molecular testing in symptomatic individuals, regardless of age. A large variation is observed between individual estimates within this cluster. These discrepancies are supposedly due in part to internal variations in PCR amplification protocols (conventional or real-time technique, 16S target fragments, or 16S–23S intergenic spacer region of bacterial ribosomal RNA). However, the use of specific probes for B. bacilliformis or genetic sequencing confirmed the detection of this species in the tested samples. Unexpectedly, these studies pointed to a drastic reduction in the rate of B. bacilliformis infection (from 24.62% to 1.61%) over the last nine years in acute febrile patients from the Andean valleys of Peru.

Only one study detected IgG antibodies by ELISA using recombinant Pap31 antigen specific for B. bacilliformis. According to the study, the possibility of cross-reactions with Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana was ruled out in the face of positive controls confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA).7 A previous study determined that this laboratory technique is reliable, showing a sensitivity of 84.5%.17 However, the possibility of false-positive results, resulting from cross-reactions between non-taxonomically related bacterial species, should not be ruled out. It is recommended to carry out confirmatory tests using another more sensitive methodology, in particular, molecular assays.

The rate of bacterial infection diagnosed by serology was 28.21% among healthy children from six rural communities in Ecuador. Chirimoyos, Galapagos, Jacapo, Santa Rosa, Usaime, and Vega del Carmen belong to the province of Loja, located south of the Andes and on the border with Peru.7 The region is geographically close to the provinces of Piura and Zamora Chinchipe, where Oroya fever was confirmed more than 20 years ago.18,19 Findings are consistent with a previous study in which seropositivity levels (IgG-IFA) can reach up to 56% in asymptomatic carriers from endemic regions.20

The main limitation of this review was basically the lack of available literature in the last decade. This fact contributed notably to the evidence of publication bias and enormous variation between studies’ rates. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted with extreme caution if they are intended to be extrapolated to other South American countries. On the other hand, the satisfactory methodological quality and unanimity in the cross-sectional design of the selected studies, characteristics more appropriate for prevalence research. Additionally, it was possible to confirm the lack of original research on the presence of this bacterial species in countries other than Peru and Ecuador. There are the lack of implementation of highly sensitive diagnostics in health units, especially near endemic areas. Furthermore, there is no international standardization of antigens and gene fragments specific for B. bacilliformis, capable of distinguishing all phases of the infection.

Among the strengths of this review are the synthesis and contemporary evidence on Carrion's disease. Our findings show the need for more epidemiological research focused on neglected tropical diseases. Another point is that it highlighting the satisfactory methodological quality of the selected studies and the unanimity in the cross-sectional design that are the most appropriate for pooled determination of prevalence by meta-analysis. Currently, the true extent of B. bacilliformis infections in South America is unknown, due to the lack of research, evaluation, prevention and epidemiological control. This review serves as a basis for, in the near future, financial resources to be directed to new research and to the monitoring of this infection that has been constantly ignored until now.

We recommend that public administrators focus their efforts on a quality health system that is accessible to all. Specialized health services with different levels of technology should be integrated by technical, logistical and management support systems for primary care units. Expanding training for inexperienced professionals and restructuring local health services are necessary actions to control this disease.

ConclusionLaboratory diagnosis of the Carrion's disease remains neglected in South American countries. B. bacilliformis infections have represented a considerable disease burden in Peru and Ecuador. However, there has been a gradual reduction in the rates of this bacterial infection in acute febrile patients in the Peruvian Andean valleys over the last five years.

CRediT authorship contribution statementCristiane F.O. Scarponi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Reviewing & Editing and Project administration; Cecília M.M. Anjos and Alice F. Silva: Data curation and Validation; Laura A. Xavier: Investigation and Validation; Felipe C.M. Iani: Formal analysis and Visualization; Mauro A.F. Guimarães: Investigation, Validation and Writing-Original draft. All authors read and final approval of the version to been submitted.

Ethical approvalAs this study was based on information retrieved from published studies, it did not require any ethical approval.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grants from public, commercial, or non-profit sector funding agencies.

Conflict of interestThe authors declared that they had no competing interests.

Data availabilityThe datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.