Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)—one of the fastest globally spreading diseases—is a chronic metabolic disorder characterized by elevated blood glucose levels. It has been suggested that the composition of gut microbiota plays key roles in the prevalence of T2DM. In this study, a novel approach of large-scale data mining and multivariate analysis of the gut microbiome of T2DM patients and healthy controls was conducted to find the key compositional differences in their microbiota and potential biomarkers of the disease.

MethodsFirst, suitable datasets were identified (9 in total with 946 samples), analyzed, and their operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were computed by identical parameters to increase accuracy. The following OTUs were merged and compared based on their health status, and compositional differences detected. For biomarker identification, the OTUs were subjected to 9 different attribute weighting models. Additionally, OTUs were independently analyzed by multivariate algorithms (LEfSe test) to verify the realized biomarkers.

ResultsOverall, 23 genera and 4 phyla were identified as possible biomarkers. At genus level, the decrease of Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, Paraprevotella, and [Eubacterium] hallii group in T2DM and the increase of Prevotella, Megamonas, Megasphaera, Ligilactobacillus, and Lachnoclostridium were selected as biomarkers; and at phylum level, the increase of Synergistota and the decrease of Euryarchaeota, Desulfobacterota (Thermodesulfobacteriota), and Ptescibacteria.

ConclusionThis is the first study ever conducted to find the microbial compositional differences and biomarkers in T2DM using data mining models applied on a widespread metagenome dataset and verified by multivariate analysis.

La diabetes tipo 2 (DT2), una de las enfermedades de más rápida propagación a nivel mundial, es un trastorno metabólico crónico caracterizado por niveles elevados de glucosa en sangre. Se ha sugerido que la composición de la microbiota intestinal tiene papeles esenciales en la prevalencia de la DT2. En este estudio, se lanzó un enfoque novedoso de minería de datos a gran escala y análisis multivariado del microbioma intestinal de pacientes con DT2 y controles sanos para encontrar las diferencias clave en la composición de su microbiota y los posibles biomarcadores de la enfermedad.

MétodosEn primer lugar, se identificaron conjuntos de datos adecuados (9 en total con 946 muestras), se analizaron y sus unidades taxonómicas operativas (OTU) se calcularon mediante parámetros idénticos para aumentar la precisión. Las OTU posteriores se fusionaron y compararon en función de su estado de salud, y se detectaron las diferencias de composición. Para la identificación de biomarcadores, las OTU se sometieron a 9 modelos diferentes de ponderación de atributos. Además, las OTU se analizaron de forma independiente mediante algoritmos multivariados (prueba LEfSe) para verificar los biomarcadores realizados.

ResultadosEn general, se identificaron 23 géneros y 4 filos como posibles biomarcadores. A nivel de género, se seleccionaron como biomarcadores la disminución de Bacteroides, Methanobrevibacter, Paraprevotella y el grupo [Eubacterium] hallii en la DT2 y el aumento de Prevotella, Megamonas, Megasphaera, Ligilactobacillus y Lachnoclostridium; y a nivel de filo, el aumento de Synergistota y la disminución de Euryarchaeota, Desulfobacterota (Thermodesulfobacteriota) y Ptescibacteria.

ConclusiónEste es el primer estudio de este tipo que encuentra las diferencias en la composición microbiana y los biomarcadores en la DT2 utilizando modelos de minería de datos aplicados a un conjunto de datos metagenómicos generalizados y verificados mediante análisis multivariado.

Diabetes is one of the oldest diseases known in human history.1 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) was first defined as a component of metabolic syndrome and is characterized by a lack of insulin secretion by pancreatic β cells, tissue insulin resistance, and an inadequate response to insulin secretion.2 With disease progression, insufficient insulin secretion results in a lack of glucose homeostasis, causing hyperglycemia.3 The leading causes of the T2DM epidemic are the overall increase in obesity, sedentary lifestyle, high-calorie diets, and the aging population, which has quadrupled the prevalence of T2DM.4

A healthy human body carries millions of microorganisms which form a system called the human microbiota. The genomes that form the human metagenome represent a diverse array of microorganisms, including bacteria, archaea, and viruses. Bacteria are the most abundant members of the human microbiota, competing with the number of cells in the human body.5 Intestinal microbiota is a key player to maintain our homeostasis through various pathways affecting the intestinal barrier function,6 immunomodulation,7 liver health,8 and many other areas.

Intestinal microbiota dysbiosis is an essential factor in the rapid development of insulin resistance in T2DM, by possibly altering intestinal barrier functions, metabolic pathways, and host signaling, which can be directly or indirectly related to insulin resistance.9 Thousands of metabolites derived from gut microbiota interact with epithelial, hepatic, and cardiac cell receptors and modulate the host physiology. The exact molecular mechanisms have not yet been discovered; however, the proposed mechanisms include the destruction of the intestinal barrier and its association with insulin resistance.10,11

Data mining is the extraction or the discovery of knowledge from large data sets and is defined as the process of discovering significant new connections, trends, and patterns by analyzing large amounts of data.12 Data mining and machine learning are routinely employed in bioinformatics due to the accessibility of an immense amount of unexplored data.13 Biological data analysis can lead to discovering new knowledge embedded in datasets and expand our knowledge across various fields of biological sciences such as genetics, neuroscience, microbiology, and medicine.14

We describe below the first use of large-scale metagenomics analysis to find the key differences in microbiota composition in healthy and T2DM individuals using data mining and multivariate analysis to identify the possible biomarkers of T2DM.

Material and methodData set collectionThe dataset for this study was constructed using keyword Entrez search in PubMed and European Molecular Biology Laboratory European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) (last searched Sep. 2021). All studies on the correlation between T2DM and microbiome were identified (74 studies total), and projects on T2DM and human gut microbiota were selected. Projects that required committee approvals or authorizations for access were excluded, resulting in a total of 9 studies containing 946 samples. Dataset was screened for missing values, and the corresponding SRA data of the 16S rRNA region (V1–V3 or V3–V5) and metadata were downloaded from the EMBL-EBI (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/services) servers in FASTQ.GZ format (Supplementary Table 1. A detailed workflow of data collection and the study accession numbers are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Analysis of metagenome (microbiome profiling)Dataset was imported to QIAGEN CLC Microbial Genomics Module Version 22 software, and sequences were quality filtered according to Kuo, Rau15 with a few changes. The raw NGS readings were submitted for fixed-length and adapter trimming (when needed), and a unified quality control based on the number of readings. A 97% similarity threshold was used for OTUs clustering, which is derived from an empirical study that showed most strains had 97% 16S rRNA sequence similarity.16 Pairwise sequence alignment was used to compute the similarity between a pair of sequences as the percentage of sites that are identical in a pairwise sequence alignment. This degree of similarity is thought to be appropriate for accurate differentiation of bacteria at genus level but not at species or strain levels. The SILVA SSU database was used as the reference for the 16S rRNA sequences.17 The number of readings assigned to each OTU was estimated and normalized for each sample, and relative abundance was determined for each OTU. Afterwards, the microbiome profile of each sample was depicted based on the derived relative abundance table. Afterwards, the corresponding meta-data containing each sample case or control status was added, and 92 samples were removed due to unrelated meta-data. Finally, an individual microbiome profile for each of the 9 selected studies and a merged profile was generated.

Data miningThe merged abundance table was created by pooling the abundance table of all the studies and then imported into RapidMiner software (RapidMiner, Inc. Headquarters One Boston Place, Suite 2600, Boston, MA 02108, USA). The health status and the relative abundance of each phylotype were assigned as target (label) and regular (ordinary) attributes (or features), respectively. The data mining algorithms were applied to the dataset to determine the most important microbial features (or biomarkers) between healthy and T2DM patients.

Attribute weightingA total of 9 attribute weighting algorithms (Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Relief, Uncertainty, Deviation, Correlation, Chi-squared, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Information gain, Information gain ratio) were applied to the data set to compute the correlation between each regular attribute to the target attribute based on a specific algorithm, with 1 indicating the highest possible separation possibility. As each model uses a specific statistical approach to calculate the weights (see14,18,19 for more information), the estimated weight for each attribute may be different. Therefore, the count of assigned weights with values>0.75 were extracted for every phylotype, and features with, at least, 1 count were selected as possible biomarkers.20

Multivariate analysisThe linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe) algorithm was used to find statistically significant, differentially abundant prokaryotes (or biomarkers) between healthy and T2DM samples. The following criteria were used to select the biomarkers: Alpha-value for the factorial Kruskal–Wallis test among classes=0.05, Alpha value for the pairwise Wilcoxon test between subclasses=0.05, and T threshold on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features>2. Analysis was performed using the Galaxy platform (https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/). Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the workflow of data collection, data mining, and multivariate analysis employed in this study.

Results and discussionResearchers have tried to find a unique microbial profile(s) in diseases such as T2DM,21 obesity,22 non-alcoholic fatty liver disease,23 gynecological disorders, and slow transit constipation,24 among others.25 The ultimate goal of these studies was to find the microbe(s) which can be used as disease biomarkers in an attempt to better understand the correlation between the gut microbiome and the disorder, and possibly improve the disorder by changing the microbiota composition toward a healthier ecosystem.26

In this study, a total of 9 projects containing 946 samples were selected and downloaded for separate and pooled analysis. The samples were trimmed, quality controlled, and filtered based on their number of readings, and after adding their corresponding meta-data, a total of 843 samples were first analyzed by an identical method, and the microbiome profile was determined for each one of the studies. Next, the OTU table of all studies was merged to determine the key microbial groups differing in the relative abundance in healthy and T2DM samples. This approach gives us with a broader perspective on the important microbial players in T2DM, when the samples were pooled together and analyzed using a uniform analysis method which minimizes the analysis error of each sample. Finally, the merged abundance tables were used as raw data for data mining and multivariate analysis.

Data set collectionIn this study, a total of 9 projects were selected for analysis. PRJNA719138, PRJNA661673, PRJNA629382, PRJNA579996, PRJNA541332, PRJDB9293, PRJNA246266, PRJNA321230 and PRJEB25715 contained 37, 180, 53, 19, 430, 74, 58, 37 and 58 samples, with 120, 33, 9, 333, 49, 18, 24 and 37 healthy samples and the rest T2DM samples, respectively; while 0, 0, 33, 3, 38, 1, 13, 13 and 2 samples were deleted due to unrelated meta-data or low sequence quality, respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

Dataset analysisMicrobiome profiling of each projectThe microbiome profile of each of the 9 projects was first constructed using a unified analysis method. Then, the relative abundances of prokaryotes at phylum and genus taxonomic levels were explored in the 843 samples. Overall, 76,607,304 OTUs were detected (Supplementary Table 2). The OTUs were allocated to 88 phyla, 181 classes, 326 orders, 402 families, and 1238 genera. The microbiome profile of each project is presented for the phylum and genus taxonomic levels, with emphasis on the most abundant taxa. Due to differences in sampling methods, geographical location, age, lifestyle and other such factors, some variations in profile of projects were expected.

The most abundant phyla in both the healthy and T2DM samples were Firmicutes (Bacillota), Bacteroidota, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteriota, Verrucomicrobiota, and Euryarchaeota while the most abundant genera were identified as Bacteroides, followed by Prevotella_9, with variations in their abundance in each study. Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4 illustrate the most abundant phyla and genera in each study.

Merged microbiome profilingSupplementary Fig. 3 shows the microbial profiles showed a diverse distribution across studies, making it challenging to find unique biomarkers with almost the same pattern of distribution. Our merging approach has been postulated to address this problem by overcoming inter- and intra-studies variations. For example, significant variations in microbial profiles of Parkinson's disease urged researchers to develop a greater harmonized meta-analysis tool(s).27 In line with the previous studies, here, we used a comprehensive approach to overcome individual study variations, such as compositional differences and abundance alterations to locate matching attributes of microbiota across the studies distinguishing between healthy and T2DM individuals. At this stage, samples were pooled and analyzed as 2 collective groups: healthy and T2DM. Results are shown at 2 taxonomic levels of phylum and genus as follows.

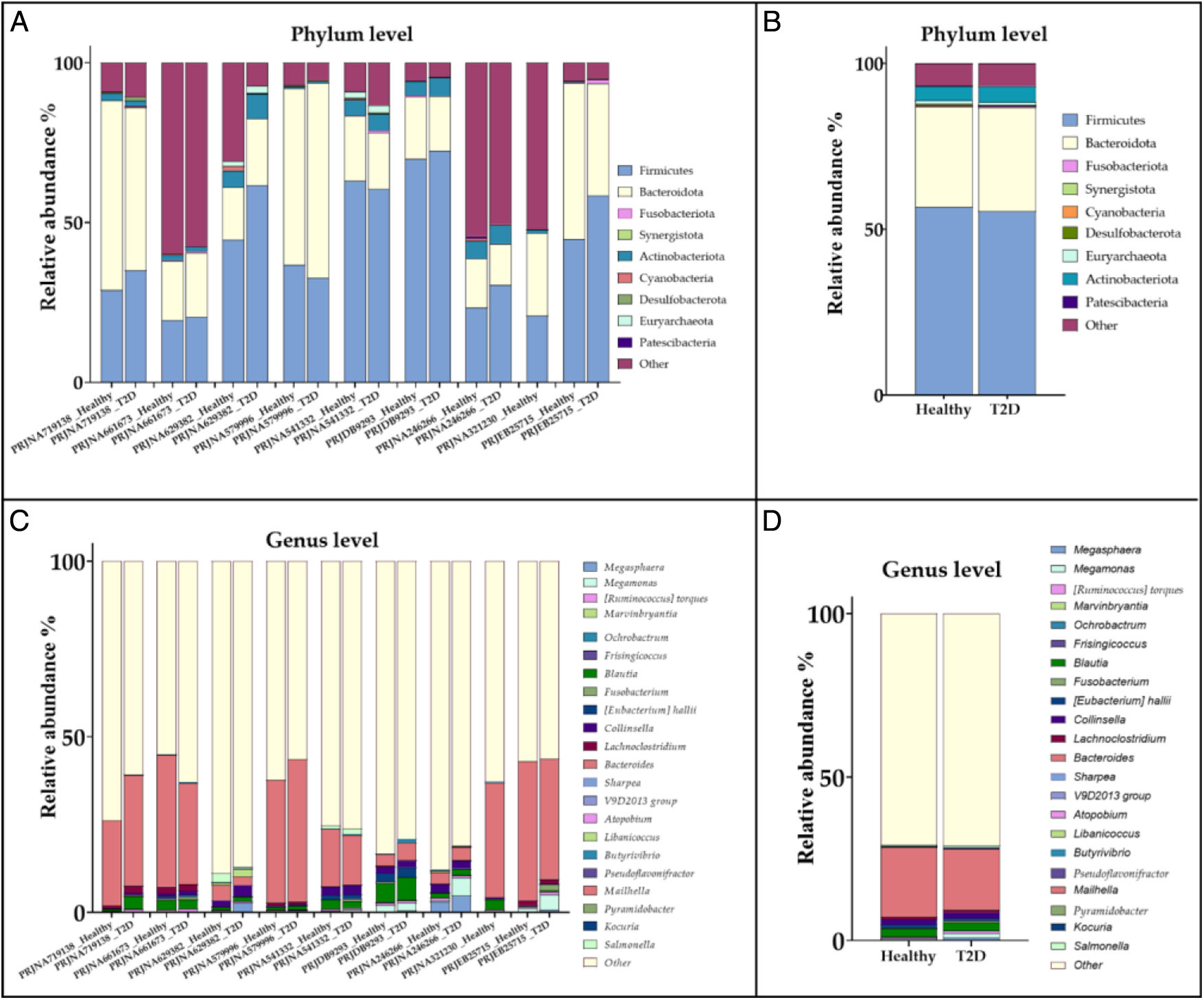

PhylumOverall, Firmicutes (Bacillota) and Bacteroidota were the 2 most abundant phyla in both states; however, in the T2DM samples, a 1.34% decrease in Firmicutes (Bacillota) and a 1.07% increase in Bacteroidota were reported. Similarly, we found that in the gut microbiome of T2DM patients, the relative abundance of Firmicutes (Bacillota) was significantly lower than their healthy counterparts. In contrast, a different study stated that the relative abundance of Firmicutes (Bacillota) increased while Bacteroidota decreased in T2DM patients.28 Variations in findings can be due to differences in sample sizes, geographical variations, dietary differences, and other such factors, thus emphasizing the need for a unified meta-analysis. In addition, in our study, Proteobacteria and Actinobacteriota (Actinomycetota) were also noticeable, with an abundance of 4.92% and 4.30% in healthy samples and 5.16%, and 4.84%e in T2DM samples, respectively. Fig. 1 illustrates the complete microbiome profile of healthy and T2DM samples, as well as the relative abundance of the top 10 most abundant phyla (Supplementary Table 5).

Merged microbiome profile of healthy and T2DM samples at phylum and genus level. (A and B) Microbiome profile of healthy (A) and T2DM (B) groups at phylum level acquired by merging all the 9 studies. (C) Relative abundance of all healthy and T2DM samples at phylum level showing the abundance of the top 10 most abundant phyla. For easier comparison, the remaining phyla are pooled together and depicted as “other”. (D and E) Microbiome profile of healthy (D) and T2DM (E) groups at genus level, acquired by merging of all the 9 studies. (F) Relative abundance of all healthy and T2DM samples at genus level showing the abundance of the top 20 most abundant genera. For easier comparison, the remaining genera are pooled together and depicted as “other”.

At genus level, Bacteroides was the most abundant genus in both healthy and T2DM samples, which accounts for 21.52% of microbiota in healthy samples and 18.7% in T2DM samples. The negative correlation between T2DM and this genus has been previously reported by Gurung, Li29 and Li, Chang.30 On the other hand, Prevotella_9 was positively associated with T2DM, with a relative abundance of 11.2% in T2DM patients vs 8.47% in controls, as observed by Tao, Li.31 Compared to our findings, the analysis of 134 diabetic patients and 37 nondiabetic controls revealed that the relative abundance of Prevotella was significantly higher in the control group. Differences in lifestyle, geographical location, and age group can be attributed to the differences in observations. Fig. 1 shows the complete microbiome profile of healthy and T2DM samples at genus level, as well as the relative abundance of the top 20 most abundant genera (Supplementary Table 6).

Data miningData mining models have been widely used to extract new knowledge from biological datasets, including metagenomic data.32–34 The predictive power of machine learning algorithms has enabled us to classify the imbalanced protein sequences and calcium transporters,18,35 find the underlying features contributing to some diseases,14,36 and draw evolutionary patterns of some viruses.19 The high power of machine processing allows researchers to analyze a massive amount of raw data, which is almost impossible to analyze by conventional methods.37 Metagenomic analysis based on machine learning has been used to predict the type of diseases and define general microbial dysbiosis.38 It has even been suggested that big data mining of microbiome datasets paves the road for precision medicine.39

In this study, the relative abundance table of metagenomic analysis was used as the raw dataset for data mining regarded as an ordinary attribute (or feature), and the feature with the 2 classes of healthy and T2DM was allocated as the label (or target) attribute. A total of 9 attribute weighting models were used on the dataset to identify the biomarkers at phylum and genus levels.

PhylumAt phylum level, Firmicutes (Bacillota), Bacteroidota, Fusobacteriota, Synergistota phyla were allocated, at least, 2 weights>0.75 by the used attribute weighting models followed by Actinobacteriota (Actinomycetota), Cyanobacteria, Desulfobacterota (Thermodesulfobacteriota), Euryarchaeota and Patescibacteria phyla, which gained weights>0.75 by 1 of the attribute weighting models.

GenusAt genus level, 80 genera were deemed significant by, at least, 1 attribute weighting model. Megasphaera gained the highest possible weight of 1.0 by the uncertainty attribute weighting model, followed by SVM, Info gain ratio, and Info gain (0.93, 0.84, and 0.65, respectively). Megamonas and [Ruminococcus] torques group also gained weights>0.75 according to 3 models. Furthermore, Marvinbryantia, Ochrobactrum, Frisingicoccus, Blautia, Fusobacterium, [Eubacterium] hallii group, Collinsella, and Lachnoclostridium were allocated significant weights by the attribute weighting models. In addition, the genera Bacteroides, Sharpea, V9D2013 group, and Atopobium gained weights>0.75 by, at least, 1 attribute weighting model (Supplementary Table 7 shows the complete list of 80 differentially important genera selected by attribute weighting models).

Fig. 2 shows the microbiome profile of each study and the collective microbiome profile of healthy and T2DM samples at phylum and genus levels showing the relative abundance of the most differentially significant taxa that received weights>0.75 by, the at least, 1 attribute weighting model.

The microbiome profile of each study according to the 9 attribute weighting models. (A) Relative abundance of the top 9 most differentially important phyla in each project. (B) Relative abundance of all healthy and T2DM samples at phylum level showing the relative abundance of the top 9 most differentially important phyla selected by the attribute weighting models. (C) Microbiome profile of each study at genus level showing the relative abundance of the top 22 most differentially important genus in each project. (D) Relative abundance of all healthy and T2DM samples at genus level showing the relative abundance of the top 22 most differentially important genus selected by the attribute weighting models. In each figure the rest of the taxa are pooled together and depicted as “other” for easier comparison.

Numerous methods have been proposed for the comparison or biomarker discovery in metagenomic data, such as MEGAN, STAMP, UniFrac, MG-RAST, as well as statistical tests such as T-tests or Fisher's exact tests. However, these methods do not specify biological class explanations to establish statistical significance, biological consistency, and effect size estimation for the proposed biomarkers. To overcome this drawback, the LEfSe test has been developed.40 LEfSe determines features, such as genes, organisms, clades, and OTUs most likely to explain inter-group or inter-class differences by using standard tests for statistical significance assessment with additional tests encoding the biological consistency and the effect relevance. This method has been used in the discovery of biomarkers that best explain the effect differentiating phenotypes of interest in mastitis,41 allergic condition,42 depression,43 hepatitis,44 and diabetes.45–47

LEfSe test was used to determine the taxa most likely to explain the differences between the 2 classes and identify the possible biomarkers by combining standard tests for statistical significance with additional tests encoding effect relevance and biological consistency.

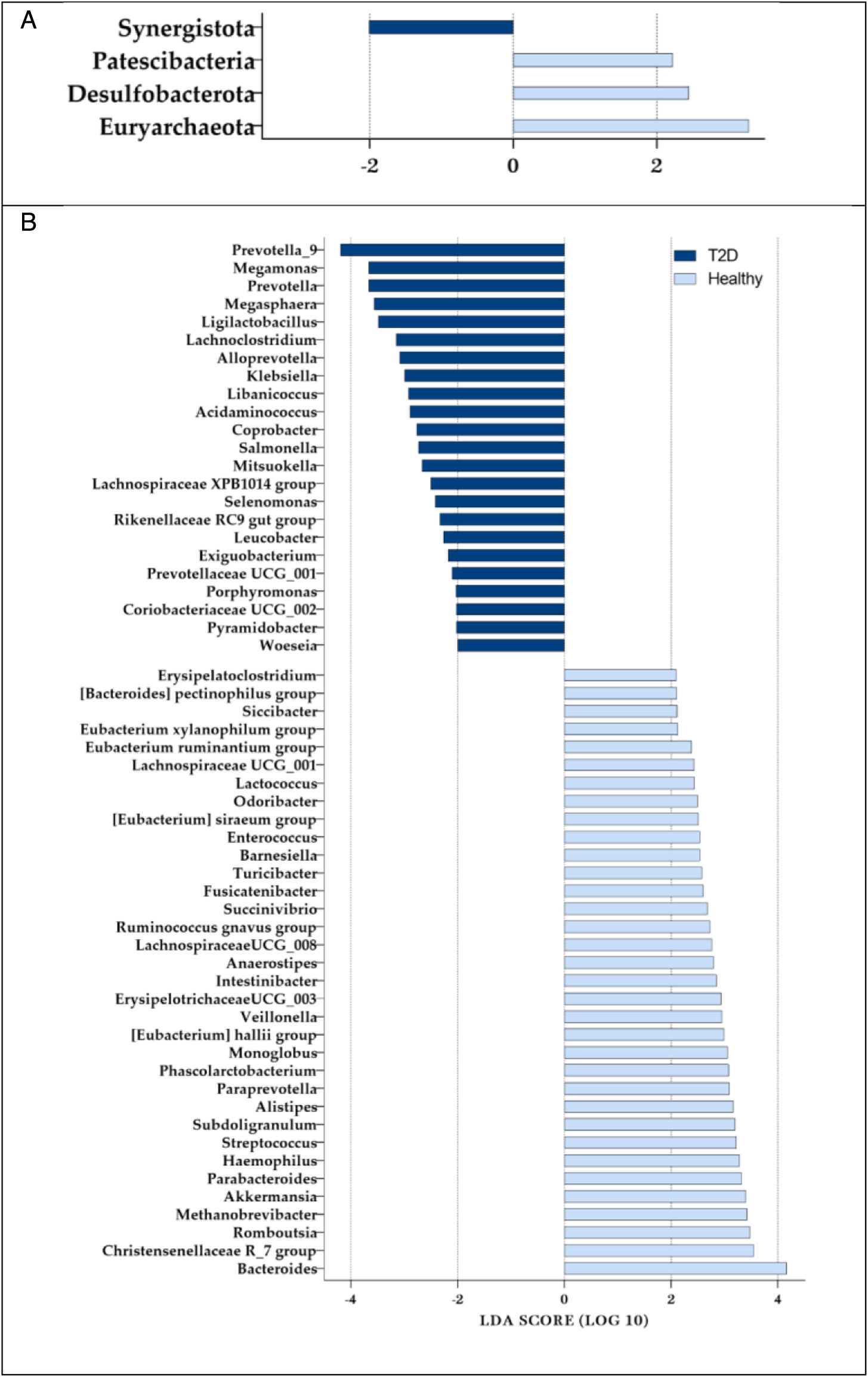

PhylumThe main biomarkers that distinguish T2DM from healthy samples at phylum level were discovered by LEfSe test. As shown in Fig. 3A, Synergistota, with an LDA score of 2.01 (P=0.006), was deemed the only overexpressed phylum in T2DM samples. However, 3 phyla were more abundant in healthy samples; Euryarchaeota, with an LDA score of 3.29 (P<0.001) was the most overabundant phylum in healthy samples (Supplementary Table 8).

GenusAt genus level, 58 genera were discovered by the LEfSe test to have the potential to act as a biomarker for the diagnosis of T2DM (LDA score>2.0). The most remarkable genera were Prevotella_9, with an overwhelming overabundance in the T2DM samples, gaining an exceptional LDA score of 4.19 (P=0.0322); in the other group, Bacteroides was overabundant in the healthy samples gaining the LDA score of 4.16 (P value=0.0118). Prevotella, Megamonas, and Megasphaera were also outstandingly underabundant in the healthy group, with an LDA score of >3.5 (P<0.01); however, the genus Christensenellaceae R_7group was overabundant in the same group. Ligilactobacillus, Lachnoclostridium, and Alloprevotella were also found to have a meaningfully higher presence in the T2DM group (LDA score>3.0; P<0.02); on the other hand, Romboutsia, Methanobrevibacter, Akkermansia, ParaBacteroides, Haemophilus, Streptococcus, Subdoligranulum, Alistipes, Paraprevotella, Phascolarctobacterium, and Monoglobus had a meaningfully higher presence in the healthy group (LDA score>3.0; P<0.05). The complete list of 58 biomarkers at the genus level and their LDA score is shown in Fig. 3B (Supplementary Table 9).

As far as we know, this is the first study of its kind to apply data mining models to large-scale output of metagenomic analysis, followed by multivariate analysis to confirm possible T2DM biomarkers. This study provides a rational approach for the identification and the verification of T2DM biomarkers in metagenomic studies, providing a new method of biomarker verification from microbiome data.

As depicted in Table 1, by using this approach, we were able to confirm that at phylum level, Euryarchaeota (an Archaea) has an exceptionally significant (P<0.001) overabundance in healthy individuals (LDA score=3.287). Similar to our finding, Merkevicius, Kundelis48 noted the increase of Euryarchaeota after diabetic treatment in a systematic review. Both attribute weighting models and multivariate analysis showed that Desulfobacterota (Thermodesulfobacteriota) and Patescibacteria had significantly lower abundances (P=0.042 and P>0.011, respectively) in T2DM samples. In addition, the Synergistota phylum gained the highest possible weight of 1.0 by the Info Gain Ratio model and showed a significant increase (P=0.006) in T2DM patients, as noted by Bai, Wan.49

Proposed T2DM biomarkers.

| Taxonomic rank | Taxon | Changes in relative abundance |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Synergistota | ↑ |

| Euryarchaeota | ↓ | |

| Desulfobacterota (Thermodesulfobacteriota) | ↓ | |

| Patescibacteria | ↓ | |

| Genus | Bacteroides | ↓ |

| Prevotella | ↑ | |

| Megamonas | ↑ | |

| Megasphaera | ↑ | |

| Ligilactobacillus | ↑ | |

| Methanobrevibacter | ↓ | |

| Lachnoclostridium | ↑ | |

| Paraprevotella | ↓ | |

| [Eubacterium] hallii group | ↓ | |

| Veillonella | ↓ | |

| Libanicoccus | ↑ | |

| Acidaminococcus | ↑ | |

| Anaerostipes | ↓ | |

| Coprobacter | ↑ | |

| Salmonella | ↑ | |

| Mitsuokella | ↑ | |

| Enterococcus | ↓ | |

| [Eubacterium] siraeum group | ↓ | |

| Prevotellaceae UCG_001 | ↑ | |

| Erysipelatoclostridium | ↓ | |

| Porphyromonas | ↑ | |

| Pyramidobacter | ↑ | |

| Coriobacteriaceae UCG_002 | ↑ | |

Summary of the proposed T2DM biomarkers and changes in their relative abundance in the T2DM patients; the ↑ indicates an increase and ↓ shows a decrease.

At genus level, 23 genera received a weight>0.75 by attribute weighting models, and an LDA score>2.0 by the LEfSe test resulting to be appointed as a possible biomarker for T2DM. Bacteroides was significantly (P=0.011) overabundant in the healthy samples, with an exceptionally high LDA score of 4.16; this genus had also gained the highest possible weight of 1.00 by Rule attribute weighting model, confirming it as a biomarker. According to Nayman, Schwartz,50 there have been repeated reports on the negative correlation between Bacteroides and T2DM.51 In agreement with our findings, a 2023 study on 45 subjects alluded to the decrease of Bacteroides in patients with T2DM.52 Zhang, Tian53 also observed a significantly lower prevalence of Bacteroides among T2DM patients in Ürümqi (China). This observation is consistent with a systematic review of 42 human studies, which also reported similar findings on the reduction of Bacteroides in individuals with T2DM.29 Moreover, Zhao, Zhang54 conducted a clinical study that further confirmed this decrease in Bacteroides, as did the study by Zhao, Lou.55 These consistent results across various studies underscore the potential significance of Bacteroides in the gut microbiota of T2DM patients.

The higher abundance of Megamonas and Megasphaera in the T2DM samples were also deemed highly significant (P>0.0001 and =0.002) by LEfSe test (LDA score=3.66 and LDA score=3.56) and attribute weighting models (weight of >0.75 by 3 models). In accordance with our findings, a study examining the effects of treatment on T2DM patients observed that the relative abundance of Megamonas was enriched in diabetic patients vs the healthy control group, and this abundance decreased again after Metformin treatment.56 Similarly, Tang, Feng57 observed an increase in Megamonas abundance in T2DM patients of Han population. Additionally, Du, Liu58 have also nominated Megasphaera, Veillonella, and Anaerostipes as potential biomarkers for T2DM. In a 2023 study with 410 Mexican patients, Neri-Rosario, Martínez-López59 also nominated Megamonas among the most influential bacterial genera in T2DM. The overabundance of Megasphaera was further noted in diabetic patients in a study involving 102 individuals, reinforcing the association of this genus with T2DM.60 Additionally, a 2024 study also highlighted the enrichment of Megasphaera in normal weighted T2DM patients.61 Compared to our findings and these studies, a human study involving 49 subjects in New Mexico did not observe any significant differences in the levels of Bacteroidia, Megamonas, or Prevotella between T2DM and healthy subjects.62 The authors attributed this lack of significant findings to the relatively small sample size, highlighting the necessity for a unifying identification method to enhance clinical value.

In addition, Prevotella and Ligilactobacillus were significantly overabundant in diabetic patients, with an LDA score of 3.66 and 3.48, respectively. In accordance with our findings, in a study involving 110 type 1 and 2 diabetic patients and healthy controls by Ejtahed, Hoseini-Tavassol63 recorded an increase in the genera Escherichia, Prevotella, and Lactobacillus in the diabetic cohorts. A 2023 study also noted an increase in the abundance of Prevotella from the control group toward T2DM patients.64 Moreover, the observed increase in Prevotella genus has been previously documented and associated with the prevalence of T2DM in multiple studies65,66; however, other studies present contrasting results. For example, Sedighi, Razavi67 found no significant difference in their study and Zhao, Zhang54 observed a decrease in diabetic patients. These differences can be attributed to a variety of factors, including differences in ethnicity, lifestyle practices, sample sizes, and the methodologies employed in each study.

Moreover, Methanobrevibacter and Paraprevotella were observed to significantly decrease in T2DM samples, with an LDA score of >3.0. In accordance with our findings, a comparative study involving T2DM, prediabetic, and healthy controls conducted by Zhang, Tian53 observed a positive correlation between Prevotella and Alloprevotella with T2DM and a negative correlation with Paraprevotella and Bacteroides. Although the decrease of Paraprevotella species in T2DM has also been numerously reported,53,68 in contrast to our findings, a 2024 study on the microbiome of prediabetic patients found an increase in Paraprevotella abundance.69 The differences may be due to the variation diabetes status, sample size and technique, age, or lifestyle. In addition, Almugadam, Liu70 observed an increase in the abundance of Methanobrevibacter in the gut microbiome of T2DM patients taking metformin vs the non-therapeutic group, suggesting a link between Methanobrevibacter and T2DM.

Overall, despite numerous studies on the effects of T2DM on gut microbiome, a unified method of analysis of large-scale data is still needed to bridge the gap between the available literature and clinical practice. The proposed method could effectively connect findings from various studies with clinical applications and ensuring more reliable and comparable results across different research settings, potentially leading to the identification of comprehensive biomarkers for T2DM. Such biomarkers could significantly enhance our understanding of the disease and pave the way for more personalized and effective treatments in clinical practice.

Study limitationsDespite being the first study to find the microbiota biomarkers of T2DM by combining both data mining models and multivariate analysis, this study encountered limitations. In microbiota profiling, sequencing depth generally includes family and genus levels; and numerous OTUs could not be identified at the species profiling level. In addition, the number of healthy samples are more abundant vs T2DM samples; therefore, further clinical studies are needed to confirm our findings and to eliminate the effect of sample size.

ConclusionsIn this study, we used machine-learning algorithms and multivariate analysis for realizing the key microbial differences in the healthy and T2DM groups. First, we used uniformly conducted metagenome analysis to minimize any sample bias. Then, we applied machine-learning algorithms to confirm the results of the microbiome analysis. Afterwards, we applied multivariate analysis to further validate the microbial groups deemed significant in the previous steps and propose the possible biomarkers for T2DM. The proposed approach was practiced for the first time in this study on metagenomic studies and hopes to pave the road for further similar studies for finding microbial biomarkers.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFE: Conceptualization, Data mining, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Roles/Writing – original draft. HM: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Roles/Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ME: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Roles/Writing – original draft. AHB: Validation, Writing – review & editing.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

Data availability statementAll relevant data have been provided inside the article or its supplementary files or remain available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (BioProject accession PRJNA719138, PRJNA661673, PRJNA629382, PRJNA579996, PRJNA541332, PRJDB9293, PRJNA246266, PRJNA321230, and PRJEB25715).