To analyze the clinical presentation, diagnosis, management and survival of Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinomas (ATC) in the Hospitals of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain).

Material and methodsRetrospective multicenter descriptive study. Adult patients with ATC diagnosed from 2002 to 2022 were included.

ResultsOf the 43 patients included, 53.5% were women, with a mean age of 72 years (SD 10) at the time of diagnosis. Symptoms were present in 100% of the patients and the most frequent symptom was a rapidly growing mass (79.1% of the cases). Infiltration of neighboring structures (76.7%), lymph node involvement (78.1%) and distant metastasis (51.2%). The AJCC-TNM category was IVa in 9.3%, IVb in 39.5% and IVc in 51.2%. BRAFV600E determination was not performed in 74.4% and 5 of the 11 cases in which it was evaluated (45.4%) had the mutation. Active treatment was received in 76.7% of patients in the first 3 mo. Surgical approach was performed in 63.6% of the cases, with complete resection in 23.8%, and 51.5% received multimodality treatment in this period. 42.3% received active treatment during follow-up (≥ 3 mo), primarily systemic chemotherapy (72.7%), and 54.4% received multimodality treatment during this period. The median specific survival was 3.5 mo (95% CI 1.7–5.2). Factors associated with longer specific survival were initial multimodality treatment (p < 0.01) or during follow-up (p = 0.01) and initial BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment (p = 0.04).

ConclusionCAT is an infrequent and aggressive tumor that requires early, multidisciplinary, personalized and multimodal treatment.

Analizar la presentación clínica, diagnóstico, manejo y supervivencia de los carcinomas anaplásicos de tiroides (CAT) en los Hospitales de Castilla-La Mancha (España).

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo retrospectivo multicéntrico. Se han incluido pacientes adultos con CAT diagnosticados desde el año 2002 hasta el año 2022.

ResultadosDe los 43 pacientes incluidos, el 53,5% eran mujeres, con una edad media de 72 años (DE 10) en el momento del diagnóstico. El 100% de los pacientes presentaba sintomatología y el síntoma más frecuente fue masa de rápido crecimiento (79,1% de los casos). El 76,7% presentaba infiltración de estructuras vecinas, 78,1% afectación ganglionar y 51,2% metástasis a distancia. La categoría AJCC-TNM fue IVa en el 9,3%, IVb en el 39,5% y IVc en el 51,2%. En el 74,4% no se realizó la determinación de BRAFV600E y 5 de los 11 casos en los que se evaluó (45,4%) presentaban la mutación. El 76,7% de los pacientes recibió tratamiento activo en los primeros 3 meses. Se realizó abordaje quirúrgico en el 63,6% de los casos, con resección completa en el 23,8%, y el 51,5% recibió tratamiento multimodal en este período. El 42,3% recibió tratamiento activo durante el seguimiento (≥ 3 meses), fundamentalmente quimioterapia sistémica (72,7%) y el 54,4% recibió tratamiento multimodal durante este período. La mediana de supervivencia específica (SE) fue de 3,5 meses (IC 95% 1,7-5,2). Los factores asociados a una mayor SE fueron el tratamiento multimodal inicial (p < 0,01) o durante el seguimiento (p = 0,01) y el tratamiento con inhibidores BRAF/MEK inicial (p = 0,04).

ConclusiónEl CAT es un tumor infrecuente y agresivo que requiere un tratamiento precoz, multidisciplinar, personalizado y multimodal.

Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC) is an undifferentiated tumor derived from the follicular epithelium, which is infrequent and extremely aggressive. It has an annual incidence rate of 1–2 cases per million inhabitants and represents 1%–2% of all thyroid cancers.1 However, despite its low incidence rate, ATC accounts for 20%–50% of all deaths associated with thyroid cancer.2 All patients with ATC are categorized according to the TNM system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) as stage IV.3 The 1-year survival rate after diagnosis is very low. In a study published in 2017 that included 1,288 patients with unresectable or incompletely resected ATC, the median survival was 2.3 mo, and only 11.3% and 6.6% of patients survived more than 1 or 2 years, respectively,4 although there are published case series describing a 10-year survival ranging between 3% and 10% in patients without metastatic disease.5,6

ATC has a higher incidence rate in women. It generally manifests between the 6th and 7th decades of life, and unlike differentiated thyroid cancer, it is practically never diagnosed before the 3rd decade of life.7 Similarly, unlike thyroid lymphomas, the presence of autoimmune thyroid disease is not an associated risk factor for the development of ATC.7

It is essential to make the differential diagnosis of this entity with other rapidly growing masses in the anterior cervical region, such as thyroid lymphoma, sarcoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, or pathological lymph nodes due to aggressive neoplasms of the aerodigestive tract, since these conditions have different therapeutic approaches.

The management of ATC requires a multidisciplinary team to assess therapeutic options, as well as the risks and benefits of different treatments. Although it is an oncological emergency, there are not many published series of ATC in the literature. Despite advances in the treatment of other oncological processes, the prognosis of ATC remains bleak and justifies research to focus on this disease. The objective of this work is to present our experience with the clinical presentation, diagnosis, management, and survival of ATC in the hospitals of the Public Health Service of Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM), Spain.

Material and methodsWe conducted a descriptive, retrospective, and multicenter study of adult patients with ATC diagnosed in hospitals of Castilla-La Mancha from 2002 through 2022. The inclusion criteria were the presence of ATC, receiving health care in SESCAM, and being ≥ 18 years. Patient selection was conducted either in collaboration with the Pathology department or from the coded diagnoses in discharge reports.

Variables analyzed- •

Sociodemographic variables: gender and age at the time of ATC diagnosis.

- •

Clinical characteristics related to the tumor at diagnosis: presence of autoimmune thyroid disease, symptoms, infiltration of adjacent structures, need for tracheostomy or percutaneous gastrostomy, lymph node involvement, and presence of distant metastases.

- •

Survival classification using the AJCC 8th edition criteria3:

- o

IVa. The tumor is of any size but is localized to the thyroid gland, and there is no associated lymph node involvement or distant metastases.

- o

IVb. The tumor is of any size but extends beyond the thyroid capsule, and associated lymph node involvement may be present.

- o

IVc. Presence of distant metastases.

- o

- •

Presence of the BRAFV600E mutation.

- •

Assessment of the Ki-67 proliferation index.

- •

Initial treatment (< 3 mo after diagnosis): whether patients received active or palliative treatment and the type of treatment and whether they received > 1 treatment simultaneously or sequentially (multimodal treatment) were assessed. The following treatment modalities were analyzed:

- o

Surgical intervention.

- o

Systemic chemotherapy (CT) and therapeutic regimen.

- o

Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (RT).

- o

BRAF/MEK inhibitors (dabrafenib + trametinib).

- o

- •

Treatments at the follow-up (≥ 3 mo after diagnosis): during this period, as in the initial period, it was analyzed whether the patient received active or palliative treatment, multimodal treatment, as well as the therapeutic interventions that were conducted.

- •

Follow-up time (months). Determined from the date of pathological confirmation of ATC to the date of data analysis.

- •

Specific survival (SS) (months). Determined from the date of pathological confirmation of ATC to the date of death.

- •

Patient status: dead or alive at the follow-up.

SS data, as well as patient status, were analyzed in June 2023 (at least 12 mo after the diagnosis of the last patient included in this series).

Statistical analysisFor quantitative variables, the results are expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]) or mean (standard deviation [SD]). Categorical variables are expressed as absolute values, proportions, or percentages. For comparisons of proportions, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used. Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate SS. To assess the effect of other factors (initial AJCC-TNM stage, initial or follow-up multimodal treatment, and initial treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors) on SS, the Log-Rank test was used. The significance threshold adopted for all tests was p < 0.05. The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS V25 software.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Drug Research Ethics Committee of the Guadalajara Health Area (Ref: 2022.47.PR) with exemption from informed consent signature. The study was conducted in full compliance with the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice, and researchers followed the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

ResultsA total of 43 patients met the inclusion criteria (53.5% were women, with a mean age at diagnosis of 72 years [SD, 10]). A total of 18.6% had a prior autoimmune thyroid disease.

At the time of diagnosis, 100% of the patients exhibited symptoms associated with ATC. The symptoms, as well as the presence of infiltration of adjacent structures, lymph node involvement, and distant metastases at the time of diagnosis, are shown in Table 1. A tracheostomy was performed in 51.2% of the cases, while a percutaneous gastrostomy for nutritional support was performed in 23.3% of the cases. At the time of diagnosis, the AJCC-TNM stage was IVa in 9.3%, IVb in 39.5%, and IVc in 51.2% of the cases.

Symptoms associated with the diagnosis of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC), presence of involvement of adjacent structures, lymph node involvement, distant metastases.

| Symptoms | |

| Rapidly growing mass (n = 34) | 79.1% |

| Hoarseness (n = 22) | 51.2% |

| Dyspnea (n = 15) | 34.9% |

| Dysphagia (n = 18) | 41.9% |

| Other symptoms (weight loss, cervical pain, odynophagia, cervical abscess, pneumonia and bone metastasis pain) (n = 13) | 34.2% |

| Infiltration of adjacent structures (n = 31) | 76.7% |

| Lymph node involvement (n = 32) | 78.1% |

| Distant metastases (n = 22) | 51.2% |

The Ki-67 proliferation index was available in 8 patients (18.6%), and the median was 40% (IQR, 35–47.5%). The BAFV600E determination was not performed in 74.4% of the included patients, while 5 of the 11 patients in whom this determination was performed presented the mutation (45.4%).

A total of 76.7% of the patients included in this study received active treatment within the first 3 mo after diagnosis, while the remaining 10 patients (23.3%) received palliative-symptomatic treatment from the time of diagnosis. Table 2 shows the type of initial treatment received, and the type of multimodal treatment. A complete tumor resection was achieved in 5 patients (23.8%) of the 21 who underwent surgical treatment. On the other hand, as described in Table 2, 17 patients (51.5%) received CT, and the most frequently used therapeutic regimen was combined carboplatin + taxol (n = 8; 47.1% of those on CT). Regarding the treatment received during follow-up, 57.7% received palliative-symptomatic treatment; 42.3%, active treatment; and 23.1%, multimodal treatment. Table 2 describes the treatment modality received in this period, and the type of multimodal treatment. In this study, all patients who received initial or follow-up treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors had the BAFV600E mutation.

Initial and follow-up treatments (after 3 mo of diagnosis) of patients with ATC.

| Initial treatment (first 3 mo after diagnosis) | N = 43 |

| Active treatment (n = 33) | 76.7% |

| Surgical intervention (n = 21) | 63.6% |

| CT (n = 17) | 51.5% |

| RT (n = 16) | 48.5% |

| BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 2) | 6.1% |

| Multimodal treatment (n = 17) | 51.5% |

| Palliative-symptomatic treatment (n = 10) | 23.3% |

| Follow-up treatment (≥ 3 mo after diagnosis, | (n = 26) |

| Active treatment (n = 11) | 42.3% |

| Surgical intervention (n = 1)a | 9.1% |

| CT (n = 8) | 72.7% |

| RT (n = 4) | 36.4% |

| BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 3) | 27.7% |

| Multimodal treatment (n = 6) | 54.4% |

| Palliative-symptomatic treatment (n = 15) | 57.7% |

| Initial multimodal treatments (n = 17) | |

| CT + RT (n = 5) | 29.4% |

| Surgery + RT (n = 4) | 23.5% |

| Surgery + CT (n = 3) | 17.6% |

| Surgery + CT + RT (n = 3) | 17.6% |

| CT + BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 1) | 5.9% |

| CT + RT + BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 1) | 5.9% |

| Follow-up multimodal treatments (n = 6) | |

| CT + RT (n = 4) | 66.7% |

| Surgical intervention + BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 1) | 16.7% |

| CT + BRAF/MEK inhibitors (n = 1) | 16.7% |

ATC: anaplastic thyroid carcinomas; CT: chemotherapy. RT: radiotherapy.

The clinical characteristics of the patients and the type of initial and follow-up treatment received according to the AJCC-TNM stage at the time of diagnosis were analyzed, grouping patients with stages IVa and IVb for this purpose (results shown in Table 3). A total of 48.8% of the patients had stage IVa–IVb; and 51.2%, stage IVc. No significant differences were observed in relation to gender and age at diagnosis according to the stage. The type of treatment received initially and during follow-up is shown in Table 3. Significant differences were observed in relation to initial surgical treatment and complete resection according to the AJCC-TNM stage at the time of diagnosis. In the group of patients classified as stage IVc, the proportion of patients with the BAFV600E mutation was higher, and they received more targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors (dabrafenib + trametinib), which allowed surgical rescue in 1 case, although no statistically significant differences were observed.

Clinical characteristics and initial and follow-up treatments according to AJCC-TNM 8th edition classification.

| Stage IVa–IVb (n = 21) | Stage IVc (n = 22) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender (%) | 43.5 | 56.5 | 0.45 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 72.2 (SD, 10.9) | 72.3 (SD, 9.3) | 0.99 |

| BRAFV600E mutation (%) in analyzed patients | 20 | 66.7 | 0.12 |

| Initial surgical treatment (%) | 71.4 | 36.4 | 0.02 |

| Complete resection (%) | 23.8 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Initial CT (%) | 33.3 | 45.5 | 0.44 |

| BRAF/MEK inhibitors (%) | 0 | 9.1 | 0.16 |

| Initial RT (%) | 33.3 | 40.9 | 0.61 |

| Surgical treatment at the follow-up (%) | 0 | 4.5 | 0.32 |

| CT at the follow-up (%) | 14.2 | 22.7 | 0.48 |

| RT at the follow-up (%) | 12.5 | 21.4 | 0.51 |

| BRAF/MEK inhibitors at the follow-up (%) | 0 | 13.6 | 0.08 |

SD: standard deviation; CT: chemotherapy. RT: radiotherapy.

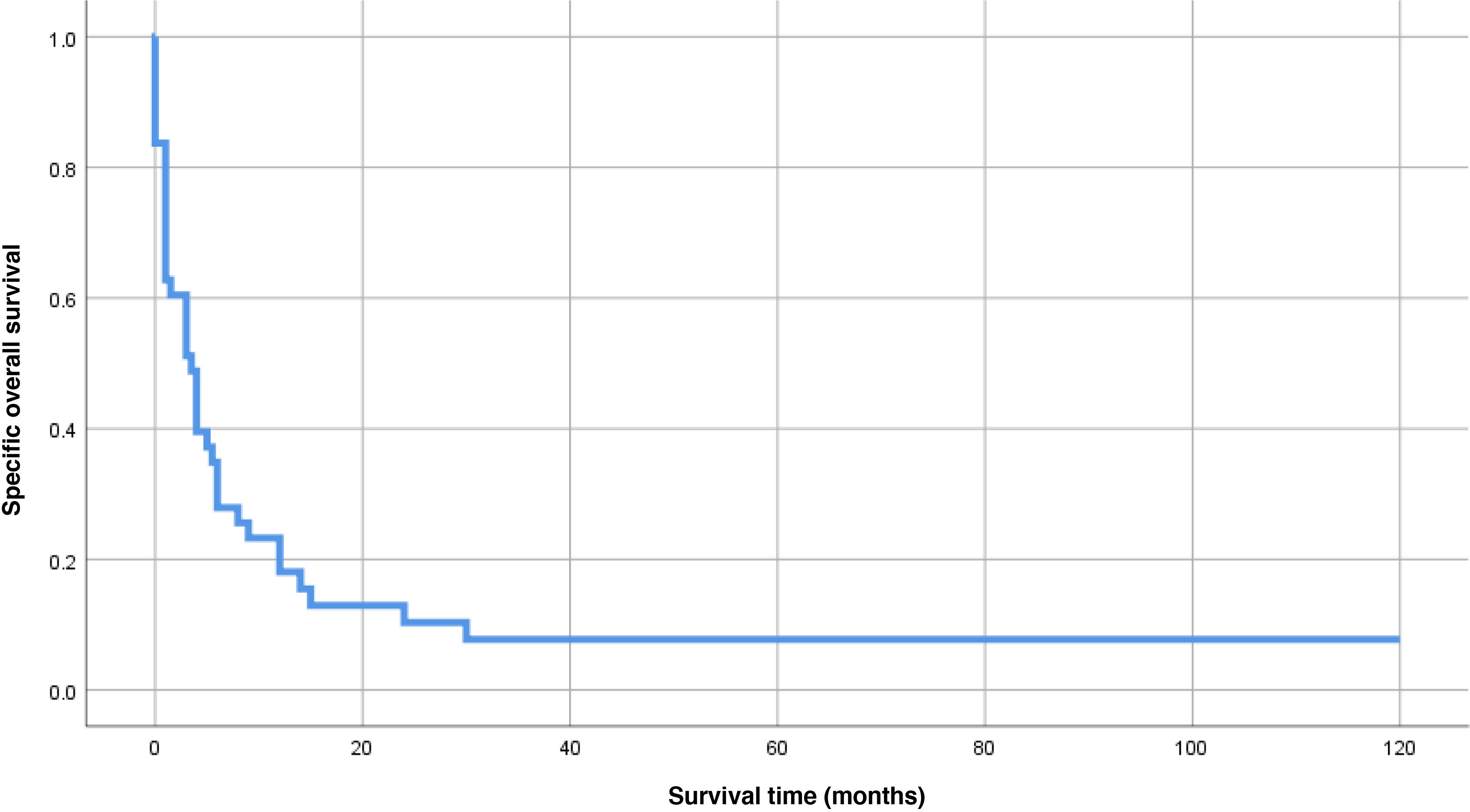

The final status of the patients included in this study was death in 95.3% of the cases, while 2 patients (4.7%) were alive and at the follow-up at the end of the study, with a median follow-up of 3.5 mo (IQR, 1–9). In the SS analysis, 2 patients were excluded because they died from causes other than ATC (9 mo after diagnosis with residual disease and 120 mo after diagnosis without residual disease). The mean SS was 14.1 mo (SD, 4.9), with a median of 3.5 mo (95% CI, 1.7–5.2) (Fig. 1). A total of 80.5% had an SS of < 1 year, while 8 patients (9.7%) survived > 1 year, and 4 of them (9.8%) > 2 years. No statistically significant differences were observed in relation to SS and AJCC-TNM stage at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 2A). The median SS in patients with stage Iva–IVb was 4 mo (95% CI, 0.3–7.7), while in those with stage IVc it was 3 mo (95% CI, 0.1–4.9) (p = 0.44). Differences were observed in the probability of SS favoring initial and follow-up multimodal treatment, and in relation to initial treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors (Fig. 2B–D). The median SS was longer in those patients on multimodal treatment vs those off this treatment, both in the initial period (9 mo [95% CI, 4.5–13.5] vs 1 mo [95% CI, 0.4–1.6], respectively, p < 0.01, Fig. 2B) and at the follow-up (12 mo [95% CI, 5.7–18.3] vs 3 mo [95% CI, 0.6–5.4], p = 0.01, Fig. 2C). Finally, the median SS in patients who were not on initial targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors was 3 mo (95%CI, 1.3–4.7), while the median SS was not reached by patients on targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors (p = 0.04) (Fig. 2D).

Kaplan-Meier analysis of specific survival (SS) based on different factors. A) SS based on AJCC-TNM stage at the time of diagnosis; B) SS based on initial multimodal treatment (< 3 mo after diagnosis); C) SS based on multimodal treatment at the follow-up (≥ 3 mo after diagnosis); D) SS based on initial treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

The diagnostic suspicion of ATC arises in the presence of a rapidly growing cervical mass that is sometimes associated with erythema or skin edema.7 It is generally associated with symptoms and signs caused by the invasion of adjacent structures or the presence of distant metastases.7 In a retrospective study that included 100 patients with ATC (52% were women with a median age of 70.5 years), similar to our study, the most prevalent initial symptom at the time of diagnosis was a rapidly growing mass, described in 66% of cases.8 In this same study,8 31% of patients had esophageal, tracheal, or both infiltrations, while 55% had lymph node involvement at the time of diagnosis and 54% had distant metastases. In our series, the presence of infiltration of adjacent structures and lymph node involvement was higher, affecting 76.2% and 78.1% of patients, respectively, while the presence of distant metastases was similar (51.2% in our case).

Given the aggressiveness of ATC, early diagnosis is fundamental, and cytological study with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is essential for this, although sometimes a core needle biopsy (CNB) is necessary to allow definitive diagnosis and molecular study.9 Immunohistochemical study is important in the confirmation of ATC. On the one hand, the Ki-67 proliferation index is usually > 30%, and stains for pankeratins (AE1/AE3) and PAX-8 often test positive. However, stains for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and thyroglobulin often test negative unless there is an associated differentiated thyroid carcinoma.10,11 Regarding molecular study, the BRAF mutation, specifically BRAFV600E is the most frequent mutation in ATC, found in 30%–70% of cases.9,12 In our series, the Ki-67 proliferation index analysis was only available in 8 patients (18.6%), with a median > 30%. On the other hand, the clinical practice guideline of the American Thyroid Association (ATA) published in 2021 on the management of patients with ATC strongly recommends performing molecular studies to rule out the presence of the BRAFV600E mutation after the diagnosis of ATC.13 In our case, the determination of this mutation was not performed in 74.4% of the included patients, although it should be taken into consideration that this work included patients diagnosed with ATC from 2002 through 2022, which may explain this result.

As in the case of diagnosis, the treatment of patients with ATC should be initiated early and personalized. The great advances made in the knowledge of ATC have led to a paradigm shift in the management of this disease, which has been reflected in the guidelines published in recent years.13–15 Therapeutic approach is usually multimodal and includes surgery, RT, and systemic treatment. However, in these patients, palliative treatment should often be considered, including measures such as pain control, nutritional support, symptom management, and assessment by a mental health team. In our series, active treatment could be administered in 76.7% of cases within the first 3 mo after diagnosis, while it was reduced to 42.3% of cases at the follow-up. In the case of resectable tumors in stages IVa and IVb, a surgical approach with total thyroidectomy and prophylactic or therapeutic central-lateral lymphadenectomy is recommended,13–15 avoiding more aggressive surgical procedures, such as laryngectomy or tracheal or esophageal resections.13 Current clinical practice guidelines consider palliative surgery in more advanced stages in selected cases, including preventive procedures where there is an imminent airway compromise, resections of locoregional disease for symptomatic metastatic disease, or in cases with a small number of distant metastases.13–15 In this study, surgical treatment could be performed in 71.4% of patients with stage IVa–IVb and in 36.6% of cases of stage IVc. Finally, in those cases with unresectable ATC during the initial evaluation, if after the administration of RT, systemic CT, or BRAF/MEK inhibitors there is a possibility of surgery, surgical treatment should be reconsidered,13 as was performed in one of the patients included in this study. The initial therapeutic regimen of systemic therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors followed by surgery has been associated with an increase in overall survival.16–18 In stage IVc ATC, systemic CT with doxorubicin, taxanes, and platinum derivatives has been considered the treatment of choice, either alone or associated with intensity-modulated RT.13–15 In patients with ATC and the BRAFV600E mutation, targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors (dabrafenib and trametinib), approved since 2018 by the FDA, is the first-line therapy according to the ATA guidelines13 in stages IVc and unresectable IVb in which RT is not administered, with a strong level of recommendation.

The therapeutic advances experienced in the management of this entity have led to a significant improvement in survival in patients with ATC. In a retrospective study published in 2020, the median survival was 9.5 mo.16 The factors that were statistically significantly associated with an improvement in SS in this study were the diagnosis of ATC during the 2017–2019 period vs the 2000–2013 period (HR, 0.5 [95% CI, 0.38–0.67]; p < 0.001), personalized therapy (HR, 0.49 [95% CI, 0.39–0.63]; p < 0.001), treatment with immunotherapy (HR, 0.58 [95% CI, 0.36–0.94]; p = 0.03), and surgical bailout after treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors (HR, 0.29 [95% CI, 0.1–0.94]; p = 0.02).16 In another study already mentioned,8 the SS was 26 mo, 11 mo, and 3 mo in patients with stages IVa, IVb, and IVc, respectively, and multimodal treatment was associated with an improvement in SS, but only in patients with stage IVc (HR, 1.05 [95% CI, 1.01–1.08]; p < 0.001). In our case, the SS was also very low, and the AJCC-TNM stage was not a factor associated with significant differences, in contrast to initial and follow-up multimodal treatment of patients, as well as targeted therapy with BRAF/MEK inhibitors.

This work has a series of limitations. On the one hand, it is a retrospective study where the different treatments received by patients were not randomized, and there is no control group. On the other hand, despite being a multicenter study, the number of patients included is lower than that of other published series. In addition, the Ki-6 The Ki-67 proliferation index is not available in most cases, so the SS analysis could not be performed based on this parameter. Furthermore, molecular study is also not available in many cases, since current clinical practice guidelines were published after the inclusion of most cases, and the determination of the BRAFV600E mutation is not available in most hospitals in Castilla-La Mancha. Finally, in our case, treatment with BRAF/MEK inhibitors was only used in patients with the BRAFV600E mutation, which limits the results when analyzing the influence of targeted therapy on the survival of patients with ATC included in this series. However, it has the strength of being a multicenter study that reflects the real-life clinical management of patients with ATC from the perspective of a public health system. In conclusion, ATC remains an aggressive tumor with low survival that requires early, multidisciplinary, personalized, and multimodal therapeutic management. More multicenter studies are needed to assess whether the therapeutic advances of recent years in the management of this entity have contributed to improving the survival of patients with ATC.

None declared.