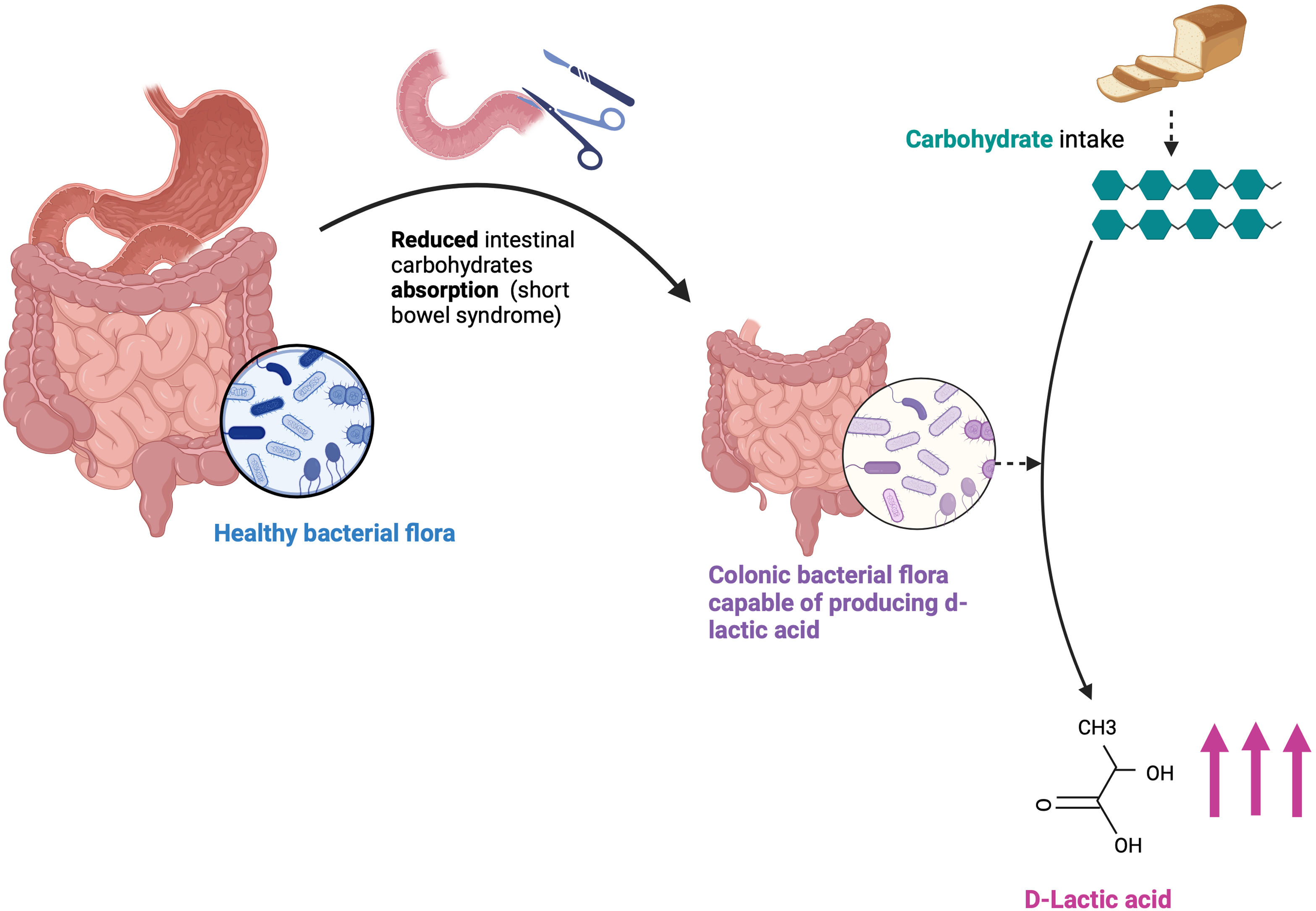

d-Lactic acidosis is an uncommon cause of acidosis that occurs in patients with short bowel syndrome (SBS). Reduced intestinal absorption surface leads to carbohydrate malabsorption, fermented by abnormal colonic bacterial flora, resulting in elevated d-lactate levels. It should be suspected in SBS patients who exhibit typical neurological symptoms without other apparent causes, along with metabolic acidosis with normal l-lactate levels. Treatment involves correcting acidosis and managing bacterial overgrowth with non-absorbable antibiotics.

This report presents a case of a patient on teduglutide for SBS who experienced an episode of d-lactic acidosis. To date, there are no documented cases in the literature of similar episodes in adult patients undergoing therapy with GLP2 analogs.

La acidosis D-láctica es una causa poco frecuente de acidosis que tiene lugar en pacientes con síndrome de intestino corto (SIC). La disminución de la superficie de absorción intestinal condiciona una malabsorción de carbohidratos que son fermentados por la flora bacteriana anormal del colon, produciéndose una elevada cantidad de D-lactato. Se ha de sospechar en pacientes con SIC que presenten sintomatología neurológica característica sin otra causa que la explique, acompañada de una acidosis metabólica con niveles de L-lactato normales. El tratamiento se basa en corrección de la acidosis y del sobrecrecimiento bacteriano con antibióticos no absorbibles.

Se presenta un caso de un paciente en tratamiento con Teduglutida por SIC donde se observa un episodio de acidosis D-láctica. Hasta el momento no se dispone en la literatura de otros casos de pacientes adultos en tratamiento con análogos de GLP2 en los que se contemplen dichos episodios.

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is defined as the presence of <200cm of small intestine in continuity.1 SBS is frequently associated with malabsorption, diarrhea, steatorrhea, malnutrition, and dehydration. SBS represents the primary pathophysiological mechanism underlying chronic intestinal failure, which is characterized by a reduction in intestinal function below the minimum necessary for the absorption of macronutrients and/or water and electrolytes, thus necessitating IV supplementation to maintain health and/or growth.1 In patients with SBS, a rare form of acidosis—known as d-lactic acidosis—may occur, which is precipitated by bacterial overgrowth.

Teduglutide, an analog of human glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2), is the first long-term non-symptomatic treatment approved for SBS. GLP-2 is a peptide secreted by the intestinal L cells located in the ileum, which enhances portal and intestinal blood flow, inhibits gastric acid secretion, and reduces intestinal motility.2 Teduglutide preserves mucosal integrity by promoting intestinal repair and growth by increasing of villus height to crypt depth ratio.2 Its approval is based on the STEPS studies,3 which observed a significant reduction in the need for parenteral nutrition (PN) and even complete independence from PN in up to 20% of patients in the teduglutide-treated group vs placebo 2 years after starting therapy.2

This article describes a case of d-lactic acidosis in a patient on teduglutide therapy for SBS.

Case report/Case presentationWe present the case of a 63-year-old man who has been monitored at the Nutrition Unit since December 2021 due to SBS. The patient is a former smoker with a past medical history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with good metabolic control, and an episode of acute intestinal ischemia of thrombotic origin back in November 2021, which required a right hemicolectomy and resection of a large part of the small intestine, leaving only a 10cm remnant of jejunum and ileum. Post-hemicolectomy, the continuity of the colon with the small intestine was preserved. Home parenteral nutrition (HPN) was started with a nocturnal regimen of 12h at the end of December 2021, with an approximate volume of 1500mL/day, progressively increasing at the follow-up to reach 2300mL in October 2023.

After nearly 2 years of intestinal adaptation, treatment with teduglutide was started on October 31st, 2023. The initial dose was 2.8mg/day (0.05mg/kg of body weight) and, following weight gain and good tolerance to the drug without significant adverse effects, the dose was up titrated to 3mg/day. Disease progression was favorable, with a slow and gradual reduction in the volume of HPN down to 1000mL, and the cycling time was reduced to 8h by the end of March 2024.

In early April 2024, during a routine blood test, the patient, who was asymptomatic at the time, showed a decreased pH (7.26) and bicarbonate (17.9mmol/L) without any signs of active infection, inflammation, or elevated lactate levels in the arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. It was decided to increase the acetate in the HPN.

A week later, 5 months after starting treatment with teduglutide, the patient presented to the emergency department with acute instability, ataxia, weakness, some euphoria, and mild dysarthria, describing a sensation “as if he were drunk,” without prior alcohol consumption. He denied feverish sensations or recent GI disturbances and had not experienced hyperglycemia or ketosis. He was hemodynamically stable, afebrile, with intense thirst but good urine output. In the detailed interview, he denied increased carbohydrate intake in recent days but reported consuming more oral nutritional supplements than usual, including protein yogurts.

The emergency blood test was performed (biochemistry and venous blood gas analysis as shown in Table 1), revealed the presence of metabolic acidosis with an elevated anion gap and normal lactate levels. Suspecting d-lactic acidosis, d-lactate levels were requested from the reference lab. We sent the sample extracted to our lab, where it was properly maintained for shipment to the corresponding lab. Treatment with bicarbonate and IV fluids was initiated, and the patient was advised to reduce oral carbohydrate intake. Hours later, there was significant clinical improvement, and the follow-up ABG analysis showed the resolution of the acidosis.

Analytical evolution.

| First time at the emergency setting (04/19/2024) | Resolution of the episode at the emergency setting | Follow-up after resolution of the condition (05/07/2024) | Normal value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7.16 | 7.43 | 7.38 | 7.35–7.45 |

| pCO2 (mmHg) | 39 | 41 | 41 | 41–53 |

| HCO3 (mmol/L) | 13.3 | 27.2 | 24.3 | 22–29 |

| GAP anion (mmol/) | 18 (High) | 7–14 | ||

| Ketonemia (mmol/L) | 0.2 | |||

| Creatinin (mmol/L) | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.2 | |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 51 | 79 | ||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 96 | 85 | 74–106 | |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 141 | 138 | 136–145 | |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4 | 4.3 | 3.5–5.1 | |

| Chlorine (mEq/L) | 113 | 98–107 | ||

| l-Lactato (mmol/L) | 0.9 | 1.3 | 0.9–5.30 | |

| Plasm Osm calculated (mmol/kg) | 295 | 275–295 | ||

| Ammonium (mmol/L) | 36 | 16–60 | ||

| d-Lactate (mmol/L) | >1 | 0.15 | <0.25 |

d-Lactic acidosis is a rare form of lactic acidosis seen in patients with malabsorption, primarily in SBS.4 It was first described in humans in 1979 by Oh et al.,5 who reported the case of a 30-year-old man with SBS who presented with peculiar neurological signs and severe metabolic acidosis due to d-lactate.5

There are 2 optical isomers of lactic acid: l-lactate and d-lactate.6 Both can be metabolized to pyruvate through the action of specific enzymes, l-lactate dehydrogenase and d-lactate dehydrogenase.6 In human tissues, l-lactate is produced from pyruvate during anaerobic carbohydrate metabolism, making l-lactate the predominant isomer.6 An important feature of lactate biochemistry is that while l-LDH catalyzes a reversible interconversion between l-lactate and pyruvate, human D-LDH irreversibly catalyzes the conversion of d-lactate to pyruvate. Therefore, d-lactate is not produced from pyruvate in human cells, and the normal plasma concentration of d-lactate is only about 1:100 that of l-lactate.7

Humans produce a very small amount of d-lactate, compared to the bacteria residing in our GI tract, which have the ability to produce either l-lactate or d-lactate depending on the concentration of l- or d-lactate dehydrogenase enzymes present in different bacterial species.6 Additionally, some species also possess another enzyme called DL-lactate racemase, which can convert one isomer into the other.6 Previously, it was believed that humans could not metabolize d-lactate; however, it is now known that this is possible through the enzyme d-2-hydroxy acid dehydrogenase (d-2-HDH), which is present in the liver and kidneys and whose activity decreases in acidosis.6

In SBS, complex carbohydrates reach the colon after passing through the small intestine, which, due to its reduced length, cannot metabolize and digest carbohydrates (CHOs). In the colon, which is essential for this condition to happen,6,8 these unabsorbed CHOs are used by bacteria as a substrate to produce l-lactate and d-lactate as end products. The production of other organic acids also increases, leading to the acidification of the intestinal environment, which promotes the growth of acid-resistant bacteria that produce more d- and l-lactate while inhibiting d-2-HDH, thus creating a vicious cycle where d-lactate production exceeds the capacity for elimination9 (Fig. 1).

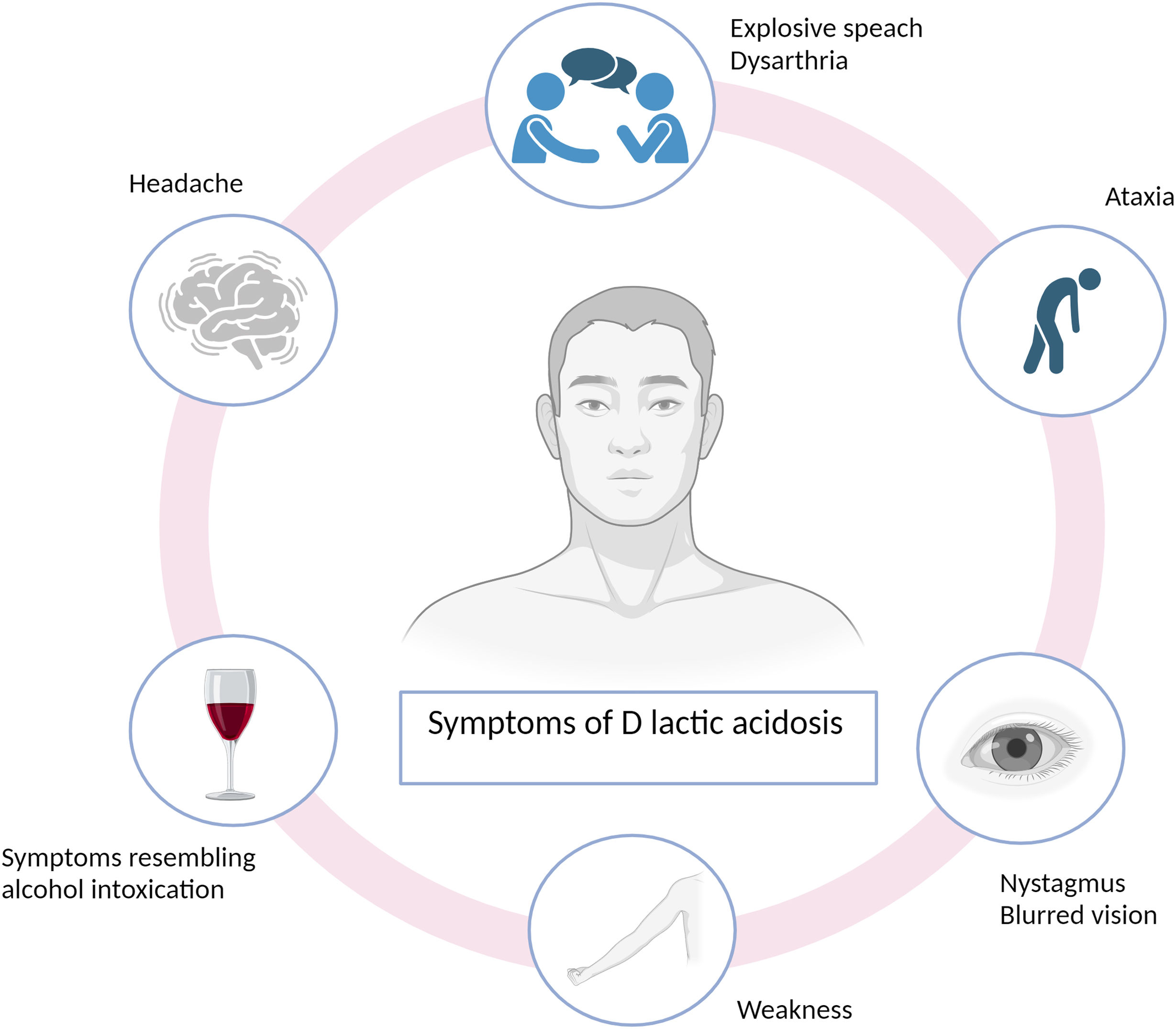

d-Lactic acidosis, also known as “d-lactic encephalopathy,” presents with characteristic symptoms, including several neurological signs, including ataxia (muscular incoordination), gait disturbances, muscle weakness, headache, nystagmus (involuntary eye movements), blurred vision, depression, explosive speech, or symptoms resembling intoxication,8 as prominently exhibited by our patient (Fig. 2). Therefore, despite being rare, suspicion should arise in patients with intestinal absorption abnormalities who develop neurological disturbances without other apparent causes.6 However, d-lactic acidosis is often underdiagnosed because neurological symptoms are frequently attributed to alternative etiologies.10

Initially, neurological signs were thought to result from the direct toxic effect of d-lactate on the brain,5 with decreased levels of d-2-HDH in the central nervous system proposed as a potential mechanism. However, it is now recognized that there is no difference in d-lactate concentration between blood and cerebrospinal fluid.11 Furthermore, d-lactate levels do not correlate with the clinical presentation.9 Consequently, it is understood that neurological symptoms may not be directly linked to d-lactate but rather to other organic acids produced in the colon, which could be potentially neurotoxic.9

Regarding analytical determinations, as observed with our patient, the concentration of l-lactate is not useful and generally remains within normal range. It is crucial to measure d-lactate levels, which often need to be requested as an external test since they are not available in many hospitals. These levels should be obtained when the patient exhibits neurological symptoms, as they rapidly decrease with symptom resolution.6 Additionally, proper and rapid processing of the sample is important, as false negatives may occur if there is a significant delay in sample processing.12

Although consensus is lacking, a plasma concentration of d-lactate ≥3mmol/L is often used to define d-lactic acidosis.13 However, in our case, the laboratory we used considered normal d-lactate levels up to 0.25mmol/L, with no values exceeding concentrations>1mmol/L. Additionally, there are instances where patients exhibit characteristic neurological symptoms in the absence of acidosis but with elevated d-lactate present.9

Various studies have shown that in patients with SBS significant changes in intestinal flora occur within 2–3 weeks of oral feeding.14,15 However, it takes months or years for a substantial amount of d-lactate to develop in feces and for the absence of its metabolism to manifest characteristic symptoms.9 In our case, the patient had SBS since 2021, 3 years before the episode of d-lactic acidosis. However, cases described by literature have been observed where the diagnosis of this episode is delayed for nearly 40 years.16

The treatment of d-lactic acidosis primarily involves correcting the acidosis with IV bicarbonate and fluids,17 while avoiding lactate-containing solutions such as Ringer's lactate that contain both d-lactate and l-lactate.9 Secondly, identifying and eliminating the causal agent, such as carbohydrates in our case, or other sources like exogenous d-lactate (lactate containing intravenous solutions, solution for peritoneal dialysis) is crucial. Discontinuing enteral carbohydrate intake will eliminate the primary source of d-lactate production, leading to a reduction in intestinal flora due to lack of sustenance.15 Carbohydrates can still be administered parenterally. Thirdly, treating bacterial overgrowth with orally administered antibiotics that are poorly absorbed and active against acid-resistant bacteria, such as metronidazole or neomycin,9 aims to alter intestinal flora and decrease d-lactate-producing bacteria. Additionally, long-term measures should be implemented to limit recurrence, potentially requiring dietary restrictions on carbohydrates, especially simple carbohydrates. Furthermore, as a novel treatment, fecal microbiota transplantation is being investigated with promising results.18

Areas of uncertaintyThere are no documented cases in the literature of d-lactic acidosis in adult patients undergoing treatment with teduglutide. We found an article on the safety of teduglutide treatment in pediatrics,19 which reported a case of a girl who experienced 2 episodes of d-lactic acidosis following the discontinuation of the treatment. Both events were resolved with the previously mentioned treatment, and teduglutide therapy was subsequently resumed. Both events occurred shortly after an interruption in teduglutide treatment. The investigator reported the first event as unrelated, and the second event as related to teduglutide treatment. Both events were assessed by the sponsor as likely related to underlying disease and unlikely to be related to teduglutide treatment.

As a hypothesis, the drug-induced intestinal villi hypertrophy might promote bacterial overgrowth. However, by increasing the absorptive surface area in the small intestine, the arrival of fermentable carbohydrates to the colon should decrease, potentially reducing the incidence of d-lactic acidosis. There may be a relationship between the length of the remaining intestine and the likelihood of developing d-lactic acidosis. Therefore, the use of teduglutide could mitigate the risk of d-lactic acidosis if the length of the small intestine were longer.

Nevertheless, dysfunctional intestine after teduglutide treatment may be involved in this process, although this is only a hypothesis and further studies are needed.

From the case presented, we can only infer that the use of Teduglutide and the increased intestinal absorption surface do not prevent the occurrence of d-lactic acidosis and this complication can occur even undergoing this treatment.

Clinical practice guidelinesMajor clinical practice guidelines on nutrition, management of short bowel syndrome, and home parenteral nutrition have been reviewed. Additionally, clinical evidence on teduglutide treatment has also been examined.

Conclusions and recommendationsd-Lactic acidosis is a rare condition that should be suspected in patients with SBS and neurological symptoms without any other identifiable cause. It takes several weeks for significant changes in bacterial flora to occur, and, at least, 1 year for this condition to develop. Treatment with teduglutide and increasing intestinal absorption surface seems not prevent the occurrence of d-lactic acidosis in patients.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have reviewed and approved the data, contributed to the development and approval of the manuscript, and acknowledged the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethical approvalWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and all accompanying images.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.