Diabetes mellitus (DM) has a high health care burden. Understanding health care resource use in DM is essential for optimizing services. This study examines health care utilization among individuals with DM in Spain, comparing them to individuals without DM.

MethodsThis study analyzed data from the 2014 and 2020 European Interview Health Survey for Spain (EHISS). Participants who reported a diagnosis of DM were classified as cases and matched to controls without DM by sex, age, EHISS edition and place of residence. The dependent variables studied were hospitalizations and emergency department visits during the 12 months. Independent variables included sociodemographics, lifestyle, and comorbidity factors.

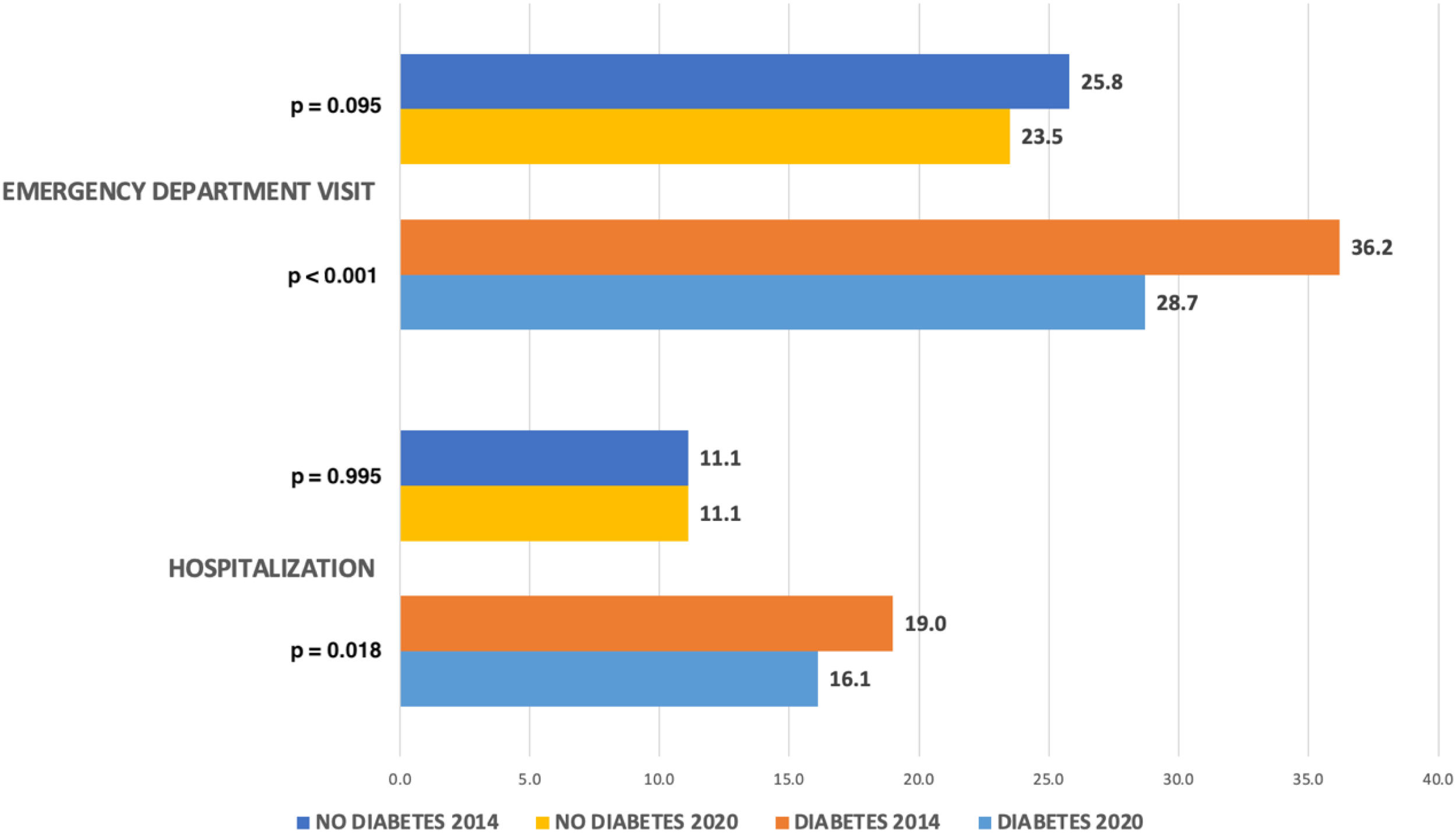

ResultsThe study included a total of 7854 participants (3927 cases and 3927 controls). A comparison between 2014 and 2020 showed fewer hospitalizations (19.0% vs 16.1%, p=0.018) and emergency department visits (36.2% vs 28.7%, p<0.001) among individuals with DM. Individuals with DM had significantly higher rates of hospitalization (17.5% vs 11.1%; p<0.001) and emergency department visits (32.3% vs 24.6%; p<0.001) vs those without DM. The identified common predictors of hospitalization and emergency department visits were poor self-rated health and cardiac ischemia.

ConclusionWe observed a higher health care utilization among individuals with DM and a downward trend from 2014 to 2020. Identifying predictors of health care use may facilitate the development of interventions to reduce health care costs. The results should be interpreted with caution due to limitations, particularly the lack of data on DM type and glycemic control.

La diabetes mellitus (DM) supone un alto coste sanitario. Comprender el uso de los recursos sanitarios en personas con DM resulta esencial para optimizar los servicios. Este estudio analiza la utilización de recursos sanitarios en pacientes con DM en España, comparándolas con personas sin DM.

MétodosSe analizaron datos procedentes de la Encuesta Europea de Salud en España (EESE) de los años 2014 y 2020. Se consideraron casos los que reportaban tener DM, y se emparejaron con controles sin DM por sexo, edad, edición de la European Health Interview Survey for Spain (EHISS) y lugar de residencia. Las variables dependientes fueron las hospitalizaciones y las visitas a servicios de urgencias en los 12 meses previos. Las variables independientes incluyeron factores sociodemográficos, de estilo de vida y de comorbilidad.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 7.854 participantes (3.927 casos y 3.927 controles). La comparación entre los años 2014 y 2020 mostró un descenso en las hospitalizaciones (19,0% vs. 16,1%; p=0,018) y en las visitas a urgencias (36,2% vs. 28,7%; p <0,001) entre las personas con DM. Estas presentaron tasas más altas de hospitalización (17,5% vs. 11,1%; p <0,001) y de visitas a urgencias (32,3% vs. 24,6%; p <0,001) en comparación con las personas sin DM. Los factores predictores comunes de hospitalización y de visitas a urgencias fueron la percepción negativa del estado de salud y la cardiopatía isquémica.

ConclusiónLas personas con DM presentan una mayor utilización de recursos sanitarios, y se observó una tendencia descendente entre 2014 y 2020. La identificación de los factores predictores de uso de recursos sanitarios puede facilitar el diseño de intervenciones para reducir los costes asistenciales. Sin embargo, los resultados deben interpretarse con precaución debido a las limitaciones, especialmente la ausencia de información sobre el tipo de DM y el nivel de control glucémico.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease with a high global prevalence whose impact on public health has steadily increased over the past decades.1 In 2024, the global prevalence was estimated at 11.1%, representing a considerable health care and economic burden.1,2 Between 2007 and 2024, global health care spending associated with DM increased by 338%, rising from 232 billion dollars to 1.015 trillion dollars.2 Expenditure in Europe amounts to 193 billion, equivalent to 19% of the global total, making it the continent with the second highest average cost per person with DM.2

In Europe, Spain ranks 5th in the number of people with DM, with an estimated prevalence in the adult population of 13.1% and 35.5% of which are undiagnosed cases. Worldwide, the proportion of undiagnosed DM reaches approximately 4 out of 10 cases, with a higher prevalence of undiagnosed individuals observed in regions with insufficient access to health care systems and low socioeconomic status.2,3 This issue is particularly relevant, as early diagnosis improves DM management, prevents complications, and enhances quality of life.4

In Spain, the average spending per person with DM was $2808.90.2 The Spanish National Health System provides universal coverage, mainly funded through taxes.5,6 The portfolio of services is extensive, although co-payment is required for drugs; however, out-of-pocket payments generally do not represent an unaffordable expense for households.5,6 Therefore, these data are particularly relevant in the Spanish context, as they highlight the elevated demand for health care services among individuals with DM in the form of frequent hospitalizations and emergency visits. This increased health care resources consumption puts a growing pressure on available resources, such as hospital capacity, specialized care, and public health expenditures, which further burdens a system already challenged by an aging population and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases.5,7

From a clinical point of view, DM entails both acute and chronic complications that increase the need for health care. Acute decompensations, such as diabetic ketoacidosis, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome, and hypoglycemia, are common causes of visits to emergency departments.8 In the long term, DM is associated with a high risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, including ischemic heart disease, stroke, and peripheral arterial disease,9 potentially leading to increased hospitalizations and follow-up in specialized outpatient clinics. As a microvascular complication, diabetic nephropathy is the leading cause of renal replacement therapy in Spain, with a significant impact on health care expenditure.10 The coexistence of multiple chronic conditions in people with DM, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, or mental illness, further increases the use of health care services and complicates the clinical management of these patients.9

Despite the size of the problem, few recent studies have systematically addressed the use of health care resources in people with DM in Spain. Most of the currently available studies are becoming outdated. Current data and understanding of recent trends in this field are essential for proper health care planning and efficient allocation of available resources.

The objectives of the present study were (1) to analyze the evolution of health care resource utilization in Spain between 2014 and 2020 among people with DM, considering hospitalizations and emergency care; (2) to compare usage between individuals with and without DM based on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and comorbidities; and (3) to identify the factors associated with greater use of health care resources in both groups.

Materials and methodsDesignWe conducted a retrospective observational study using data from the European Health Interview Survey for Spain (EHISS) from 2014 and 2020 editions. This survey was developed by the Spanish National Statistics Institute and targeted residents of Spain aged 15 years or older. Data from both editions had been collected through face-to-face interviews until March 2020, when telephone interviews began due to the restrictions following the COVID-19 pandemic.11 This change in the way the interview was conducted could lead to differences in the quality of the data collected.

The sampling design of the EHISS was probabilistic, stratified, and multistage. First, geographic units (census sections) were randomly selected, followed by a random sampling of households, and finally, one individual per household was chosen. This procedure ensured the representativeness of the general Spanish population.11

Cases and controlsParticipants who answered affirmatively to the question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have DM?” were considered cases. Those who answered negatively to the same question were classified as controls. Each case was matched with a control adjusting for sex, age, survey edition, and autonomous community of residence, to reduce potential confounding factors. Given that this classification is based on self-reported diagnoses, it may be subject to recall bias or misclassification, which could affect the reliability of case identification.12

Analyzed variablesThe dependent variables analyzed were 2 indicators of health care resource use in the past 12 months: at least, 1 hospitalization and visit to emergency services. Independent variables included sociodemographic characteristics, such as sex, age, educational level, living with a partner, and survey edition), lifestyle-related factors (BMI, self-rating of health status, active smoking, alcohol consumption, and sedentary lifestyle), and the presence of relevant comorbidities (COPD, cardiac ischemia, stroke, cancer, mental disease, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and chronic pain). Definitions and categories of variables are detailed in Table S1.

Statistical analysisWe conducted a descriptive analysis of the sample. Quantitative variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD), and those without normal distribution according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test as median and interquartile range (IQR). Qualitative variables were described as frequencies and percentages.

To compare groups, the following tests were used: Student's t-test for quantitative variables with normal distribution, Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative variables without normal distribution, and the chi-square test for categorical variables.

To identify factors associated with health care resource utilization, 2 multivariable logistic regression models were developed, one for each dependent variable. All variables collected in the study were initially included as potential predictors. Variable significance was assessed using the Wald statistic, and non-significant variables were removed through a backward elimination process. Multicollinearity was evaluated using the variance inflation factor (VIF). All tolerance values were >0.70, and all VIF values were <1.5, indicating the absence of problematic multicollinearity. Model calibration was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

SPSS Statistics software, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), was used, and a two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all comparisons.

Ethical considerationsAccess to the survey data is free and open.9 Because the data were anonymized and analyzed in aggregate, national legislation did not require written informed consent or approval by a Research Ethics Committee for medicinal products.

ResultsA total of 7854 participants were included, including 3927 cases and 3927 controls. Of these, 1912 (48.7%) were men. The mean age was 68.89 years (SD, 13.1). Table S2 shows the comparison of clinical characteristics between groups with and without DM. Compared to participants without DM, patients with DM had a significantly higher median body mass index (BMI) (27.82 vs 26.22; p<0.001), more sedentary habits (50.2% vs 41.3%; p<0.001) and unfavorable self-rated health status (62.9% vs 43.6%; p<0.001), but lower alcohol consumption (38.6% vs 48.7%; p<0.001). The prevalence of all studied comorbidities was higher in the DM group, except for cancer, for which no significant differences were found.

Table S3 illustrates the characteristics by survey edition. Comparisons between the 2014 and 2020 surveys showed an increase in mean age (69.6 vs 68.1 years; p<.001) and a modest reduction in mean BMI (27.5 vs 28.0; p<.001). Participants in 2020 had a higher level of education and a greater proportion reported favorable self-rated health (40.0% vs 33.8%; p<.001). The prevalence of mental illness (18.9% vs 23.7%; p<.001) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8.8% vs 12.2%; p<. 001) was lower in 2020 vs 2014.

Fig. 1 illustrates the evolution in health care resource use from 2014 to 2020, based on the presence or absence of DM. A significant decrease was observed in the proportion of participants with DM visiting an emergency department (36.2% vs 28.7%; p<0.001), as well as a reduction in the proportion of participants requiring hospitalizations (19.0% vs 16.1%; p=0.018).

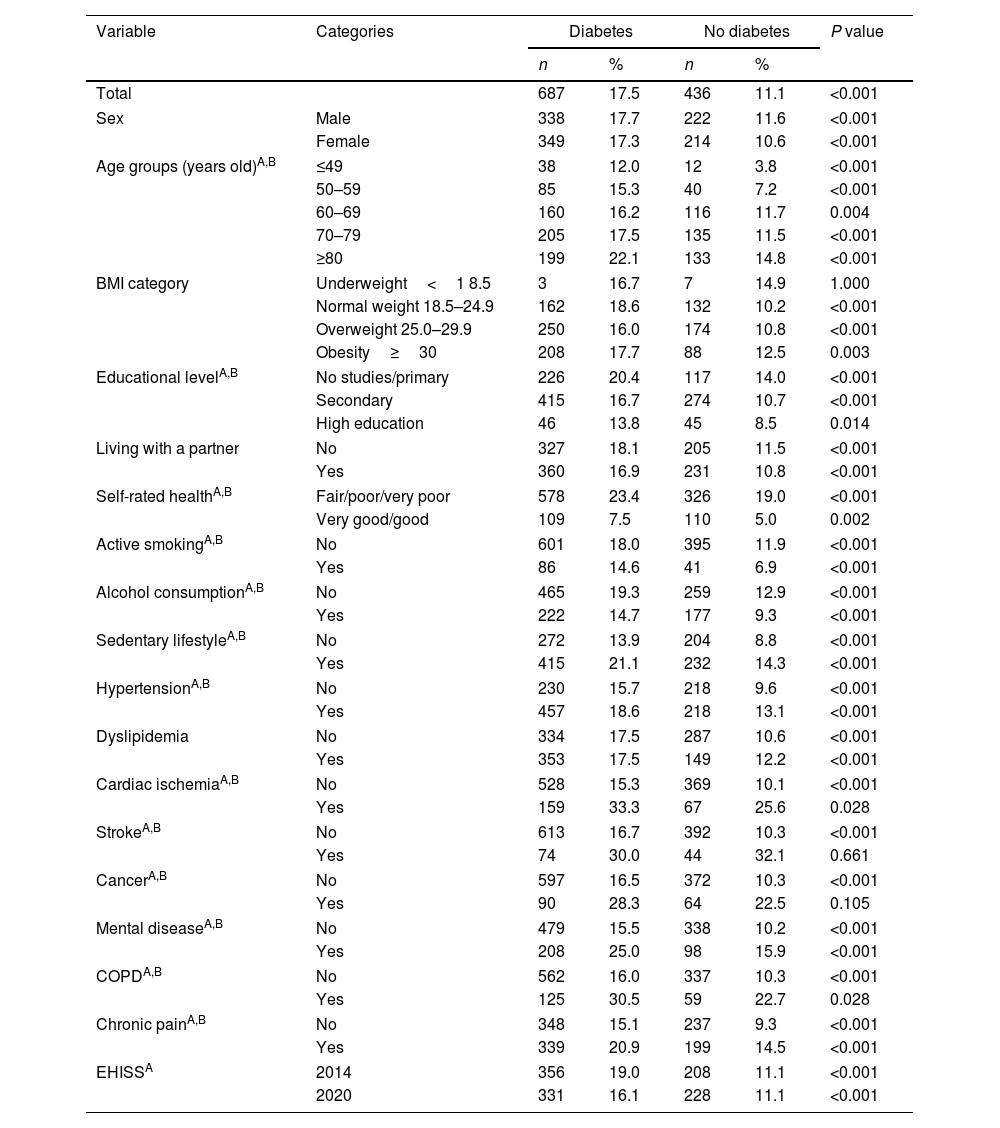

Table 1 illustrates the hospitalizations of participants with and without DM according to sociodemographic variables, lifestyle, and comorbidities, from EHISS 2014 and 2020 editions. A higher frequency of hospitalization was observed in the DM group (17.7%) vs those without DM (11.1%), with the difference being statistically significant (p<0.001). This trend persisted across most categories analyzed, except for subgroups with low weight, a history of stroke, or cancer, where no relevant differences were found.

Prevalence of hospitalization by demographic, lifestyle, and comorbidity variables among participants with and without diabetes based on the 2014 and 2020 editions of the European Health Interview Surveys for Spain (EHISS).

| Variable | Categories | Diabetes | No diabetes | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Total | 687 | 17.5 | 436 | 11.1 | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 338 | 17.7 | 222 | 11.6 | <0.001 |

| Female | 349 | 17.3 | 214 | 10.6 | <0.001 | |

| Age groups (years old)A,B | ≤49 | 38 | 12.0 | 12 | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 85 | 15.3 | 40 | 7.2 | <0.001 | |

| 60–69 | 160 | 16.2 | 116 | 11.7 | 0.004 | |

| 70–79 | 205 | 17.5 | 135 | 11.5 | <0.001 | |

| ≥80 | 199 | 22.1 | 133 | 14.8 | <0.001 | |

| BMI category | Underweight<1 8.5 | 3 | 16.7 | 7 | 14.9 | 1.000 |

| Normal weight 18.5–24.9 | 162 | 18.6 | 132 | 10.2 | <0.001 | |

| Overweight 25.0–29.9 | 250 | 16.0 | 174 | 10.8 | <0.001 | |

| Obesity≥30 | 208 | 17.7 | 88 | 12.5 | 0.003 | |

| Educational levelA,B | No studies/primary | 226 | 20.4 | 117 | 14.0 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | 415 | 16.7 | 274 | 10.7 | <0.001 | |

| High education | 46 | 13.8 | 45 | 8.5 | 0.014 | |

| Living with a partner | No | 327 | 18.1 | 205 | 11.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 360 | 16.9 | 231 | 10.8 | <0.001 | |

| Self-rated healthA,B | Fair/poor/very poor | 578 | 23.4 | 326 | 19.0 | <0.001 |

| Very good/good | 109 | 7.5 | 110 | 5.0 | 0.002 | |

| Active smokingA,B | No | 601 | 18.0 | 395 | 11.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 86 | 14.6 | 41 | 6.9 | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol consumptionA,B | No | 465 | 19.3 | 259 | 12.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 222 | 14.7 | 177 | 9.3 | <0.001 | |

| Sedentary lifestyleA,B | No | 272 | 13.9 | 204 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 415 | 21.1 | 232 | 14.3 | <0.001 | |

| HypertensionA,B | No | 230 | 15.7 | 218 | 9.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 457 | 18.6 | 218 | 13.1 | <0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | No | 334 | 17.5 | 287 | 10.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 353 | 17.5 | 149 | 12.2 | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac ischemiaA,B | No | 528 | 15.3 | 369 | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 159 | 33.3 | 67 | 25.6 | 0.028 | |

| StrokeA,B | No | 613 | 16.7 | 392 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 74 | 30.0 | 44 | 32.1 | 0.661 | |

| CancerA,B | No | 597 | 16.5 | 372 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 90 | 28.3 | 64 | 22.5 | 0.105 | |

| Mental diseaseA,B | No | 479 | 15.5 | 338 | 10.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 208 | 25.0 | 98 | 15.9 | <0.001 | |

| COPDA,B | No | 562 | 16.0 | 337 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 125 | 30.5 | 59 | 22.7 | 0.028 | |

| Chronic painA,B | No | 348 | 15.1 | 237 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 339 | 20.9 | 199 | 14.5 | <0.001 | |

| EHISSA | 2014 | 356 | 19.0 | 208 | 11.1 | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 331 | 16.1 | 228 | 11.1 | <0.001 | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

p value for difference between participants with diabetes and diabetes age and sex matched controls.

Among participants with DM, hospitalization was significantly associated with older age, low educational level, unfavorable self-rated health status, sedentary lifestyle, absence of alcohol or tobacco use, hypertension, cardiac ischemia, mental disease, and chronic pain. Additionally, hospitalization rates were significantly higher in participants from the 2014 vs the 2020 survey, showing a decrease in hospitalizations during this period. In the group without DM, similar associations were identified, except for the survey edition, which did not show significant differences.

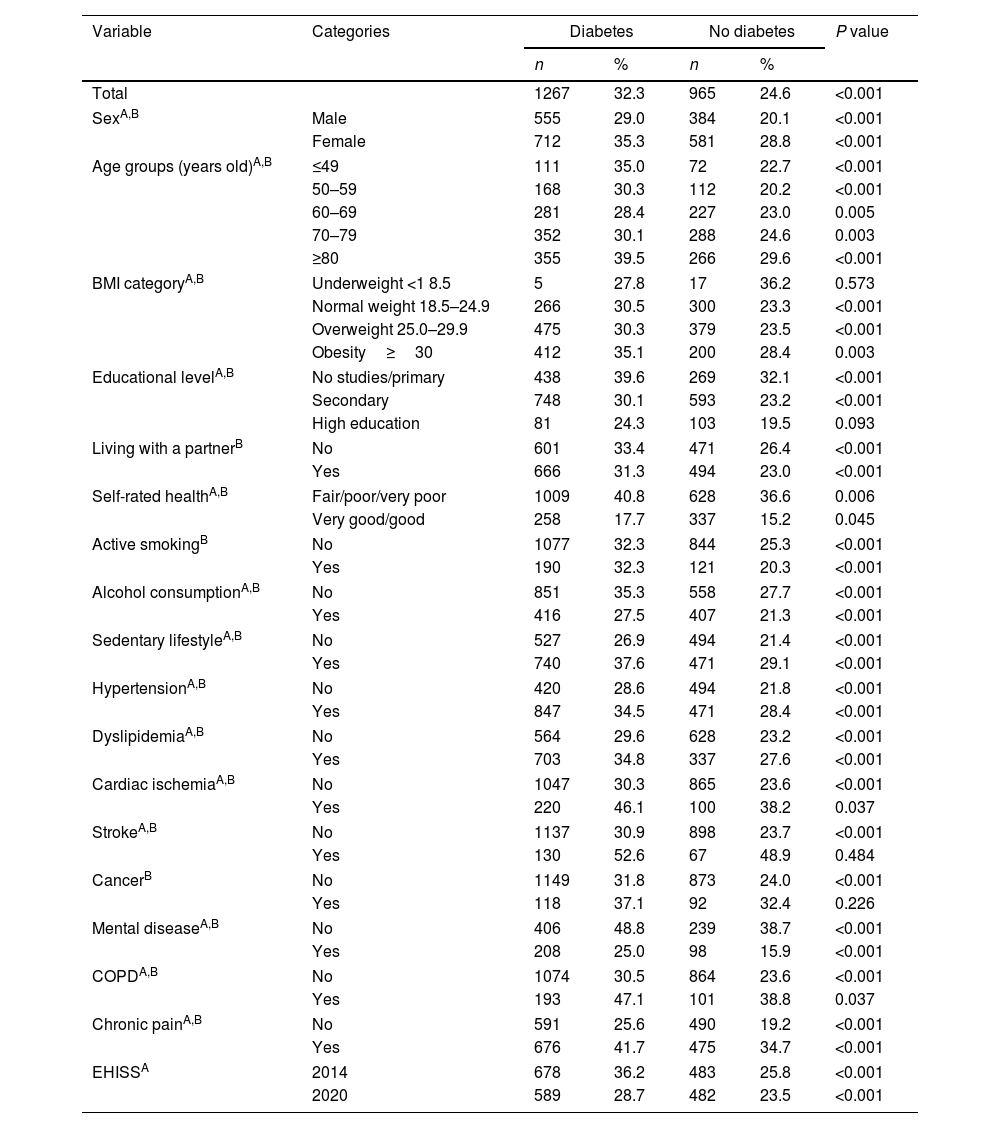

Table 2 illustrates the prevalence of emergency department visits according to sociodemographic variables, lifestyle, and comorbidities, in individuals with and without DM, based on EHISS 2014 and 2020 data. Greater use of these services was found in the DM vs the non-DM group (32.2% vs 24.6%; p<0.001). This difference persisted in most subcategories, except for individuals with low weight, higher educational level, or a history of stroke or cancer.

Prevalence of emergency department visits by demographic, lifestyle, and comorbidity variables among participants with and without diabetes based on the 2014 and 2020 editions of the European Health Interview Surveys for Spain (EHISS).

| Variable | Categories | Diabetes | No diabetes | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Total | 1267 | 32.3 | 965 | 24.6 | <0.001 | |

| SexA,B | Male | 555 | 29.0 | 384 | 20.1 | <0.001 |

| Female | 712 | 35.3 | 581 | 28.8 | <0.001 | |

| Age groups (years old)A,B | ≤49 | 111 | 35.0 | 72 | 22.7 | <0.001 |

| 50–59 | 168 | 30.3 | 112 | 20.2 | <0.001 | |

| 60–69 | 281 | 28.4 | 227 | 23.0 | 0.005 | |

| 70–79 | 352 | 30.1 | 288 | 24.6 | 0.003 | |

| ≥80 | 355 | 39.5 | 266 | 29.6 | <0.001 | |

| BMI categoryA,B | Underweight <1 8.5 | 5 | 27.8 | 17 | 36.2 | 0.573 |

| Normal weight 18.5–24.9 | 266 | 30.5 | 300 | 23.3 | <0.001 | |

| Overweight 25.0–29.9 | 475 | 30.3 | 379 | 23.5 | <0.001 | |

| Obesity≥30 | 412 | 35.1 | 200 | 28.4 | 0.003 | |

| Educational levelA,B | No studies/primary | 438 | 39.6 | 269 | 32.1 | <0.001 |

| Secondary | 748 | 30.1 | 593 | 23.2 | <0.001 | |

| High education | 81 | 24.3 | 103 | 19.5 | 0.093 | |

| Living with a partnerB | No | 601 | 33.4 | 471 | 26.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 666 | 31.3 | 494 | 23.0 | <0.001 | |

| Self-rated healthA,B | Fair/poor/very poor | 1009 | 40.8 | 628 | 36.6 | 0.006 |

| Very good/good | 258 | 17.7 | 337 | 15.2 | 0.045 | |

| Active smokingB | No | 1077 | 32.3 | 844 | 25.3 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 190 | 32.3 | 121 | 20.3 | <0.001 | |

| Alcohol consumptionA,B | No | 851 | 35.3 | 558 | 27.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 416 | 27.5 | 407 | 21.3 | <0.001 | |

| Sedentary lifestyleA,B | No | 527 | 26.9 | 494 | 21.4 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 740 | 37.6 | 471 | 29.1 | <0.001 | |

| HypertensionA,B | No | 420 | 28.6 | 494 | 21.8 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 847 | 34.5 | 471 | 28.4 | <0.001 | |

| DyslipidemiaA,B | No | 564 | 29.6 | 628 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 703 | 34.8 | 337 | 27.6 | <0.001 | |

| Cardiac ischemiaA,B | No | 1047 | 30.3 | 865 | 23.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 220 | 46.1 | 100 | 38.2 | 0.037 | |

| StrokeA,B | No | 1137 | 30.9 | 898 | 23.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 130 | 52.6 | 67 | 48.9 | 0.484 | |

| CancerB | No | 1149 | 31.8 | 873 | 24.0 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 118 | 37.1 | 92 | 32.4 | 0.226 | |

| Mental diseaseA,B | No | 406 | 48.8 | 239 | 38.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 208 | 25.0 | 98 | 15.9 | <0.001 | |

| COPDA,B | No | 1074 | 30.5 | 864 | 23.6 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 193 | 47.1 | 101 | 38.8 | 0.037 | |

| Chronic painA,B | No | 591 | 25.6 | 490 | 19.2 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 676 | 41.7 | 475 | 34.7 | <0.001 | |

| EHISSA | 2014 | 678 | 36.2 | 483 | 25.8 | <0.001 |

| 2020 | 589 | 28.7 | 482 | 23.5 | <0.001 | |

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

p value for difference between participants with diabetes and diabetes age and sex matched controls.

Among individuals with DM, emergency visits were associated with female sex, high BMI, low educational level, unfavorable self-rated health, sedentary lifestyle, no alcohol consumption, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiac ischemia, stroke, mental disease, COPD and chronic pain. Furthermore, emergency room visits were significantly higher in participants from the 2014 vs the 2020 survey, suggesting a temporal decline over this period. Similar associations were found in the group without DM, with additional differences in non-smoking and history of cancer, and no significant variation according to survey year.

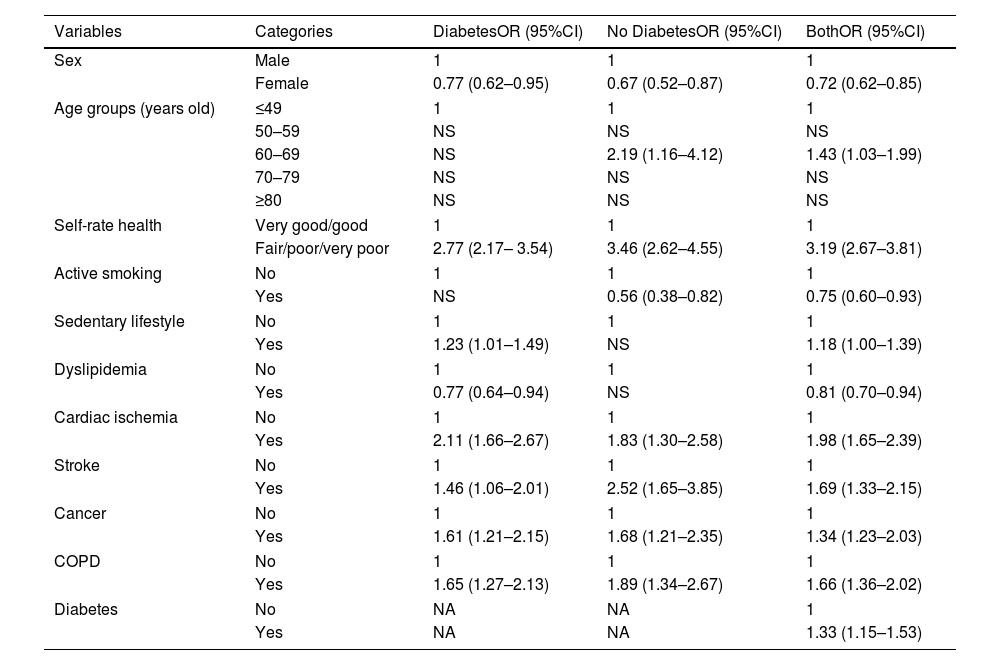

Table 3 illustrates the predictors of hospitalization based on DM diagnosis. A diagnosis of DM was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalization (OR, 1.33; 95%CI, 1.15–1.53). In the DM group, factors that increased risk included male sex (OR, 1.30; 95%CI, 1.09–1.61), unfavorable self-rated health (OR, 2.77; 95%CI, 2.17–3.54), sedentary lifestyle (OR, 1.23; 95%CI, 1.01–1.49), cardiac ischemia (OR, 2.11; 95%CI, 1.66–2.67), history of stroke (OR, 1.46; 95%CI, 1.06–2.01), cancer (OR, 1.61; 95%CI, 1.21–2.15), and COPD (OR, 1.65; 95%CI, 1.27–2.13). Dyslipidemia showed an inverse association (OR, 0.77; 95%CI, 0.64–0.94).

Predictors of hospitalization based on diabetes diagnosis.

| Variables | Categories | DiabetesOR (95%CI) | No DiabetesOR (95%CI) | BothOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.77 (0.62–0.95) | 0.67 (0.52–0.87) | 0.72 (0.62–0.85) | |

| Age groups (years old) | ≤49 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 50–59 | NS | NS | NS | |

| 60–69 | NS | 2.19 (1.16–4.12) | 1.43 (1.03–1.99) | |

| 70–79 | NS | NS | NS | |

| ≥80 | NS | NS | NS | |

| Self-rate health | Very good/good | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fair/poor/very poor | 2.77 (2.17– 3.54) | 3.46 (2.62–4.55) | 3.19 (2.67–3.81) | |

| Active smoking | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | NS | 0.56 (0.38–0.82) | 0.75 (0.60–0.93) | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.23 (1.01–1.49) | NS | 1.18 (1.00–1.39) | |

| Dyslipidemia | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.77 (0.64–0.94) | NS | 0.81 (0.70–0.94) | |

| Cardiac ischemia | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.11 (1.66–2.67) | 1.83 (1.30–2.58) | 1.98 (1.65–2.39) | |

| Stroke | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.46 (1.06–2.01) | 2.52 (1.65–3.85) | 1.69 (1.33–2.15) | |

| Cancer | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.61 (1.21–2.15) | 1.68 (1.21–2.35) | 1.34 (1.23–2.03) | |

| COPD | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.65 (1.27–2.13) | 1.89 (1.34–2.67) | 1.66 (1.36–2.02) | |

| Diabetes | No | NA | NA | 1 |

| Yes | NA | NA | 1.33 (1.15–1.53) | |

NS: not significant; NA: not applicable.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

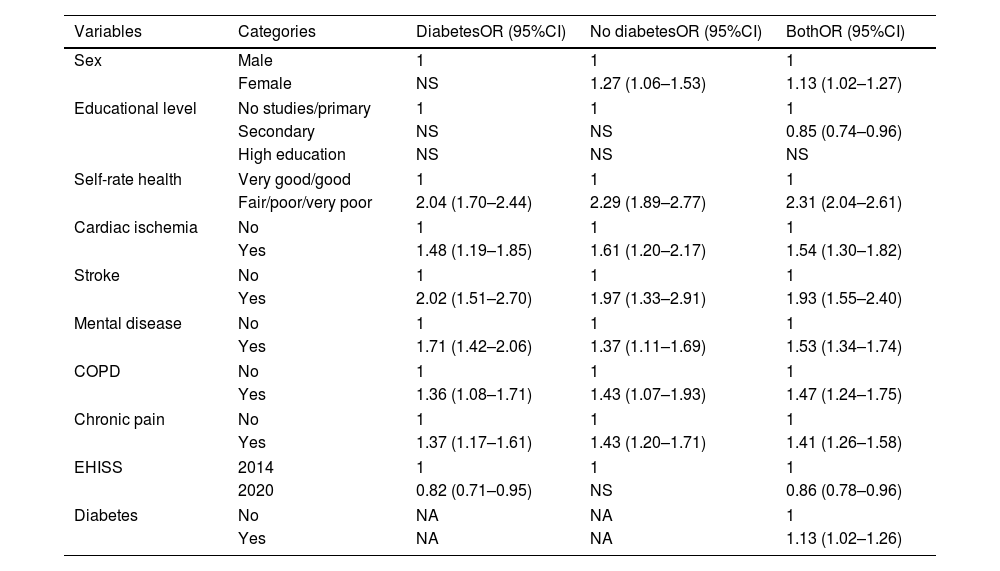

Table 4 illustrates the predictors of emergency visits based on the presence or absence of DM. A DM diagnosis was associated with a higher likelihood of using emergency services (OR, 1.13; 95%CI, 1.02–1.26). The DM group showed positive associations with unfavorable self-rated health (OR, 2.04; 95%CI, 1.70–2.44), cardiac ischemia (OR, 1.48; 95%CI, 1.19–1.85), history of stroke (OR, 2.02; 95%CI, 1.51–2.70), mental disease (OR, 1.71; 95%CI, 1.42–2.06), COPD (OR, 1.36; 95%CI, 1.08–1.71), and chronic pain (OR, 1.37; 95%CI, 1.17–1.61). Participation in the 2020 edition (OR, 0.82; 95%CI, 0.71–0.95) was associated with a lower likelihood of emergency visits. No significant differences were observed between sexes.

Predictors of emergency department visits based on diabetes diagnosis.

| Variables | Categories | DiabetesOR (95%CI) | No diabetesOR (95%CI) | BothOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | NS | 1.27 (1.06–1.53) | 1.13 (1.02–1.27) | |

| Educational level | No studies/primary | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Secondary | NS | NS | 0.85 (0.74–0.96) | |

| High education | NS | NS | NS | |

| Self-rate health | Very good/good | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Fair/poor/very poor | 2.04 (1.70–2.44) | 2.29 (1.89–2.77) | 2.31 (2.04–2.61) | |

| Cardiac ischemia | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.48 (1.19–1.85) | 1.61 (1.20–2.17) | 1.54 (1.30–1.82) | |

| Stroke | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.02 (1.51–2.70) | 1.97 (1.33–2.91) | 1.93 (1.55–2.40) | |

| Mental disease | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.71 (1.42–2.06) | 1.37 (1.11–1.69) | 1.53 (1.34–1.74) | |

| COPD | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.36 (1.08–1.71) | 1.43 (1.07–1.93) | 1.47 (1.24–1.75) | |

| Chronic pain | No | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.37 (1.17–1.61) | 1.43 (1.20–1.71) | 1.41 (1.26–1.58) | |

| EHISS | 2014 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2020 | 0.82 (0.71–0.95) | NS | 0.86 (0.78–0.96) | |

| Diabetes | No | NA | NA | 1 |

| Yes | NA | NA | 1.13 (1.02–1.26) | |

NS: not significant; NA: not applicable.

COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Our study found a significant decrease between 2014 and 2020 in the proportion of participants with DM who made at least 1 emergency department visit and in the participants who were hospitalized. These results are similar to those obtained in a study conducted in Spain that found a decrease from 2007 through 2015 in the prevalence of hospitalization of individuals with DM.13 This trend has also been observed in other studies conducted in Spain 14 and as well as in a population-based study conducted in Poland during the same period (2014–2020), where a decrease in hospitalization rates was observed among the population with DM.15 In contrast, a study conducted in Ghana showed a progressive increase in the percentage of patients with hospitalizations from 2012 through 2017 (from 7.9% up to 21.6%).16 In the United States, a study analyzed the prevalence of emergency department visits among individuals with DM and reported a 55.6% increase from 2008 to 2017.17 A study conducted in Saudi Arabia between 2011 and 2015 also observed an increase, of 21%.18 These disparities in health care utilization trends across countries worldwide may be explained by differences in access to health care systems, socioeconomic status, and barriers related to health policy.19

Declines in health care utilization observed between 2014 and 2020 may be indicative of systemic improvements in the management of DM, such as greater specialist endocrinology availability.20 Nevertheless, since our analysis lacked data on the causes of hospitalizations and emergency department visits, we cannot conclude that this trend is explained by any single factor. New non-insulin hypoglycemic drugs have recently become available with public funding in Spain. While our study does not include data on treatment or glycemic control, it is plausible that the introduction of these therapies may have contributed to improved disease management, potentially reducing complications and emergency visits among patients with DM.21 However, this remains a hypothesis that cannot be confirmed with the current data.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a significant impact in Spain, Spanish authorities implemented measures that limited the mobility of the population.22 These measures, together with the fear of infection, especially among people with different degrees of immunosuppression, including patients with DM, led to lower utilization of health care resources for reasons other than COVID-19.23 Additionally, during this period, non-urgent medical activities were suspended, prioritizing care for COVID-19-related cases.22,23 This disruption in routine care and monitoring represents a major limitation for interpreting our results during the most recent period, as it may have influenced health care utilization independently of underlying health needs. A study analyzing the impact of COVID-19 restriction measures showed a decrease in testing of glycosylated hemoglobin in the population with DM vs the same periods of the previous year.22 However, other studies have reported opposite findings, showing a deterioration in glycemic control in the context of high systemic inflammation caused by COVID-19 infection. Therefore, during the pandemic, the high rate of infections may have been a contributing factor to poorer disease control among patients with DM.24,25

Our study showed that the hospitalization rate in the population with DM was 1.6 times higher than in the population without DM, a finding consistent with other findings described in the literature.26,27 The increase in the prevalence of hospitalization with age is similar to that observed in a study conducted in Ghana in the population with DM,16 which showed a higher prevalence of hospitalization in the 75–79 age group vs the 25–29 age group.

Our study found a higher probability of hospitalization in men with DM. Although several studies in the literature have examined hospitalization rates in patients with DM by sex, results are inconsistent, probably due to gender bias, study design, and demographic and social differences. Several former studies found women have both a higher mortality and a higher risk of hospitalization due to cardiovascular disease.28

On the other hand, in our study, a positive association was observed between DM and other comorbidities such as cardiac ischemia, stroke, cancer, mental disease, COPD, and chronic pain. These findings are similar to those described in a study that reported a higher prevalence of hypertension, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, and heart failure in the population with vs without DM.26

A study conducted by Assari et al. (2020) observed a positive relationship between poor self-rated health and greater utilization of health care resources, including both emergency visits and hospitalizations.29 This finding is similar to our study conclusions. Former studies have identified self-rated health as a valid and reliable predictor of mortality.30,31 It is also consistently associated with multimorbidity,32 a factor that contributes to a higher emergency room visits and hospital admissions.

In our study, we found an association between hospitalization and being a non-smoker, although this was not statistically significant within the subgroup of patients with DM. One possible explanation is the healthy survivor effect or reverse causality, whereby individuals may adopt healthier behaviors, such as quitting smoking, following hospitalization or complications from chronic diseases.33

Similarly, we observed an inverse association between dyslipidemia and hospitalization. A possible explanation is that individuals diagnosed with both dyslipidemia and DM are usually having a stricter medical supervision and a more regular follow-up.34 This could potentially lead to a better prevention of acute complications and, as a result, a lower likelihood of hospitalization. However, further studies are needed to corroborate this hypothesis.

Regarding emergency department visits, our study showed a higher prevalence of such visits in participants with DM vs without DM. This prevalence was especially higher in women. This finding was also reported in a 2022 study conducted by Uppal et al.17 However, A prospective study led by Patel et al., conducted in the United States in 2022 revealed no differences in emergency visits between men and women with DM.35

Santo et al. demonstrated an increase in emergency visit rates as comorbidities increased.36 The same phenomenon was observed in a study conducted by Ye et al.37 The results of our study are consistent with those reported in the literature. Specifically, we found an association between mental illness and emergency visits. This is consistent with the findings from the studies conducted by Hutter et al. and Shulman et al., which proved more emergency visits and hospitalizations, and greater health care spending in individuals with DM and mental illness vs those with DM without mental illness.38

A study conducted in Mexico39 identified higher educational level as a factor associated with a higher risk of emergency visits in the population with T1DM. In contrast, our study found a higher prevalence of emergency visits in patients with DM who had only primary education or no education. This difference is probably due to social disparities and the fact that our study did not distinguish between T1DM and T2DM.

To reduce excessive utilization of health care resources in the population with DM, it is important to strengthen both primary and specialized care for these individuals, paying special attention to those with comorbidities, which are associated with greater use of these resources. Other measures could include early detection and treatment of DM and its related microvascular and macrovascular complications, as well as DM education, with the goal of reducing the prevalence of emergency visits and hospitalizations.40

Our study has several strengths. First, the large sample size increases statistical power. Second, the survey methodology is consistent and uniform throughout the study period, allowing comparison between different survey editions and analysis of trends. Third, the face-to-face interview format and anonymity increase the credibility of the information. Finally, the survey includes sociodemographic and lifestyle variables, which facilitates study of social factors.

But, our study also has limitations as well. First, a fundamental limitation of this study is the inability to distinguish between T1DM and T2DM. This represents a significant limitation on results interpretability, as these diseases possess extremely different etiologies, management, complication spectra, and health care resources utilization patterns, so caution is needed when interpreting combined data. Second, we lacked data on the degree of disease control. Health care resource utilization may differ depending on glycemic control level. Third, the diagnosis of DM was self-reported by participants, without verification through medical records. This method may be subject to certain limitations, particularly the influence of recall bias and social desirability bias, which could compromise the reliability of the information provided. Although a study conducted among the Spanish population has shown good concordance between self-reported diagnoses and health records verification.41 Fourth, since the survey questions refer to the past, recall bias may occur. Fifth, there may be non-response bias, considering that the response rate in EHISS 2014 was 74.6% and in EHISS 2020 was 72.2%.42 Sixth, while the variable “living with a partner” was available, the caregiving roles were not captured by the surveys, which would be useful to inform the relationship between social support structures and health care utilization. Seventh, our study lacked adjustment for socioeconomic status and primary care access, which are determinants of health care resources utilization that may influence both DM outcomes and service use patterns. Finally, the difference in the mode of contact for conducting the interview, due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, could affect the quality of the data collected by telephone and the comparability of these data with those collected in person. Considering these limitations, the results should be interpreted with caution.

ConclusionsDespite the downward trend in health care resource utilization among patients with DM, it remained higher vs patients without DM. Patients with DM, unfavorable self-perceived health status, and comorbidities were more likely to use health care resources. Greater attention should be given to these patients in routine clinical practice and in the design of health care strategies to prevent complications.

FundingThis work has been supported by the FIS (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias—Health Research Fund, Instituto de Salud Carlos III), and co-financed by the European Union through the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER, “Una manera de hacer Europa”): grant no. PI20/00118, by the Madrid Government (Comunidad de Madrid-Spain) under the Multiannual Agreement with Universidad Complutense de Madrid in the line Excellence Programme for uni-versity teaching staff, in the context of the V PRICIT (Regional Programme of Research and Technological Innovation), and by Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Grupo de Investigación en Epidemiología de las Enfermedades Crónicas de Alta Prevalencia en España (970970), as well as by Grupo de Investigación en Biomedicina Predictiva e Investigación Traslacional en las Enfermedades Respiratorias, Cardiovasculares y Metabólicas of the Health Research Institute of Hospital Clínico San Carlos (IdISSC).

Conflicts of interestNone declared.