Diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) is a rare precursor to lung carcinoids. We report a case of ACTH-dependent Cushing's syndrome in a 73-year-old female patient with metastatic lung carcinoid arising on a background of DIPNECH. She presented with lower limb oedema, hypokalaemia, hypertension, and de novo diabetes. Clinical suspicion for hypercortisolism was confirmed by abnormal cortisol tests. A thoracic CT scan showed multiple lung nodules suggestive of DIPNECH and biopsy of one of the nodules identified an ACTH-expressing carcinoid tumour. A PET-Ga-68-DOTATOC revealed pulmonary and multiple tumour lesions in the ganglia, bone and liver with overexpression of somatostatin receptors. A liver biopsy demonstrated involvement by a well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasia, consistent with metastasis. Hypercortisolism was managed with octreotide and metyrapone, but the patient succumbed to complications 14 months post-diagnosis. This case suggests DIPNECH's potential to progress to hyperfunctioning, metastatic carcinoids and highlights the necessity for vigilant long-term surveillance and early intervention.

La hiperplasia difusa idiopática de células neuroendocrinas pulmonares (DIPNECH) es un precursor raro de los carcinoides pulmonares. Presentamos un caso de síndrome de Cushing dependiente de ACTH en una paciente de 73 años con carcinoide pulmonar metastásico que se desarrolló en un contexto de DIPNECH. La paciente presentaba edema en las extremidades inferiores, hipopotasemia, hipertensión y diabetes de novo. La sospecha clínica de hipercortisolismo se confirmó mediante pruebas de cortisol alteradas. Una tomografía computarizada (TC) torácica mostró múltiples nódulos pulmonares sugestivos de DIPNECH y la biopsia de uno de los nódulos identificó un tumor carcinoide con expresión de ACTH. Una PET-Ga-68-DOTATOC reveló lesiones tumorales pulmonares y múltiples en los ganglios, huesos e hígado con sobreexpresión de receptores de somatostatina. Una biopsia hepática demostró afectación por una neoplasia neuroendocrina bien diferenciada, consistente con metástasis. Aunque el hipercortisolismo se trató con octreótido y metirapona, la paciente falleció por una serie de complicaciones que sobrevinieron 14 meses después del diagnóstico. Este caso sugiere el potencial de la DIPNECH para degenerar en carcinoides hiperfuncionantes y metastásicos y pone de manifiesto la necesidad de seguimiento a largo plazo e intervenciones tempranas.

Neuroendocrine tumours of the lung comprise a heterogeneous family of neoplasms classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) system into 4 histological categories: typical carcinoid (TC), atypical carcinoid (AC), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).1 Lung carcinoids (TC, low grade tumours and AC, intermediate grade tumours) account for 20–25% of all NETs and 1–2% of all lung cancers. Rarely, lung carcinoids (LC) may arise in the context of diffuse idiopathic pulmonary neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (DIPNECH) which is believed to be a spectrum of disease as the cells are histologically identical to carcinoid cells.2 Patients with DIPNECH frequently display concurrent multiple lesions along the neuroendocrine spectrum suggesting that these may represent varying stages of progression.3 Metastatic spread of LC in the context of DIPNECH has been described but seems extremely uncommon.4 Additionally, rare reports have associated the presence of DIPNECH with functioning syndromes.

Case presentationA 73-year-old woman presented to the Emergency Department with a 1-month history of peripheral oedema. Physical examination upon admission revealed hypertension (155/85mmHg); pulse, 78bpm; respiratory rate, 20 and SpO, 92%; she had bibasilar crackles and hepatomegaly on examination, cardiac auscultation was normal. Bilateral lower limb oedema was present, going all the way up to the thighs. Lab test results showed a normal hemogram and renal function, elevated γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT 640U/L, normal range 7–32) mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT 52U/L, NR 10–31); de novo diabetes (glycated haemoglobin HbA1c, 8.8%); marked hypokalaemia (serum potassium, K+ 2.5mEq/L, N 3.5–5.1); mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP, 10mg/L, N<3.0) and a normal B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP, 49pg/mL, N<100pg/mL).

The patient's past medical history included controlled hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia. She had been followed-up in Pneumology for the last 4 years due to chronic cough and dyspnoea. Pulmonary function testing showed a moderate obstructive pattern. Lung CT showed diffuse mosaic attenuation with air trapping, bronchial thickening, and multiple bilateral nodules, the largest measuring between 8mm and 12mm suggestive of DIPNECH. The patient had previously refused a biopsy of the nodule and was started on inhaled glucocorticoids along with a beta agonist, remaining under monitorization with annual thoracic imaging displaying clinical and imaging stability.

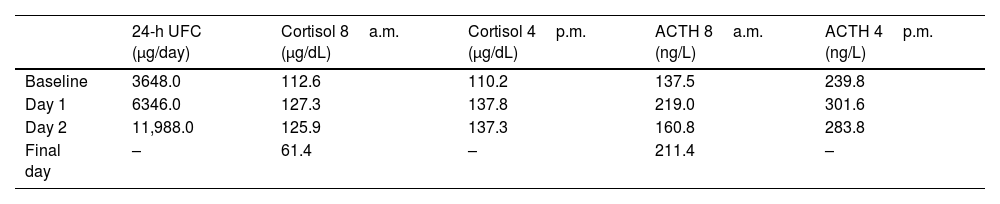

The patient was admitted for further investigation. The recent onset of peripheral oedema, diabetes mellitus, and impaired consciousness with worsening confusion and disorientation within the first days of hospitalization, along with marked hypokalemia, raised clinical suspicion of endogenous hypercortisolism, prompting screening for Cushing's syndrome (CS) (Table 1). The patient exhibited central obesity and facial fullness but no other cushingoid features. Lab test results showed a markedly increased 24-h urinary free cortisol (UFC) (UFC, 3648.0μg/day; NR, 36.0–137.0); an overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test (DST) turned out positive (cortisol, 77.5μg/dL; N<1.8). ACTH was elevated (167.1ng/L; N<63.3) and high-dose DST revealed no suppression of cortisol and UFC (Table 2), suggestive of an ectopic origin.

Cushing's syndrome screening.

| Tests | Reference values | |

|---|---|---|

| Morning serum cortisol levels | 58.0 | 6.2–19.4μg/dL |

| Morning ACTH levels | 167.1 | <63.3ng/L |

| 24-h UFC | 3648.0 | 36.0–137.0μg/day |

| Overnight 1-mg DST | 77.5 | <1.8μg/dL |

| Midnight serum cortisol levels | 83.4 | 1.7–8.9μg/dL |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; UFC, urinary free cortisol; DST, dexamethasone suppression test.

High-dose dexamethasone suppression test.

| 24-h UFC (μg/day) | Cortisol 8a.m. (μg/dL) | Cortisol 4p.m. (μg/dL) | ACTH 8a.m. (ng/L) | ACTH 4p.m. (ng/L) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3648.0 | 112.6 | 110.2 | 137.5 | 239.8 |

| Day 1 | 6346.0 | 127.3 | 137.8 | 219.0 | 301.6 |

| Day 2 | 11,988.0 | 125.9 | 137.3 | 160.8 | 283.8 |

| Final day | – | 61.4 | – | 211.4 | – |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; UFC, urinary free cortisol.

Evaluation by thoracic CT showed diffuse mosaic attenuation with bilateral lung nodules, without evident disease progression (Fig. 1). A biopsy of a pulmonary nodule demonstrated immunoreactivity to chromogranin, synaptophysin and thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1), as well as neuroendocrine cell proliferation consistent with carcinoid tumour. Further immunohistochemistry studies of the lung lesion revealed focal ACTH expression but were negative for CDX2 and somatostatin receptor subtype 2A (SST2A) expression.

A PET-Ga-68-DOTATOC was performed, revealing multiple tumour lesions located in the lung (one in the peri-hilar region, identified as the likely primary lesion, and a second lesion at the base of the right lung), as well as in the cervical, thoracic and abdominal ganglia, bone and liver (Fig. 2). A PET-FDG-F18 excluded the presence of concomitant dedifferentiated/high-grade metabolic lesions. Liver biopsy demonstrated diffuse hepatic involvement by a well differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasm expressing chromogranin and synaptophysin with a proliferative index Ki67<2%, consistent with metastasis. This lesion showed positive staining for CDX2 and SSTR2A but no expression of TTF-1 or ACTH. A diagnosis of ectopic ACTH-dependent CS in the clinical context of DIPNECH progressing to metastatic neuroendocrine tumour was established, and targeted therapy with long-acting somatostatin analogue octreotide was initiated. The patient was also started on metyrapone, which resulted in a prompt and sustained decrease in cortisol levels, as evidenced by a 24-h UFC of 38.1μg/day.

At hospital discharge, the patient remained on monthly octreotide LAR (30mg) and metyrapone (250mg daily), with controlled cortisol and serum K+ levels (K+ 4.8mEq/L). She was fully oriented with normal vital signs, and peripheral oedema was mild and limited to the ankles.

After 9 months of clinical stability, with controlled cortisol levels under SSA and metyrapone, late-night salivary cortisol levels began to rise (0.673μg/dL and 1.000μg/dL, N<0.320) prompting an increase in metyrapone to 500mg daily. Fourteen months after diagnosis, the patient presented with a femoral fracture and was admitted for surgical treatment. During hospitalization in the orthopaedic ward, she developed sepsis originating from a surgical wound, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in blood cultures. Despite targeted antibiotic therapy and surgical debridement, her condition deteriorated, progressing to septic shock. Cortisol levels were never checked during hospitalization, and no adjustments were made to her treatment. The patient passed away 30 days following admission.

Literature review and case discussionIncreasing numbers of DIPNECH cases have been described since its first formal recognition in 1992 by Aguayo et al.,5 due to increased use of high resolution CT and growing awareness of this entity. Nevertheless, it remains a rare conditions, and as a result, diagnostic criteria and prognosis remain unclear, still lacking well-established clinical practice guidelines regarding the management of this entity. According to the WHO classification, DIPNECH is a multifocal hyperplasia that occurs without any inciting injury and consists of individual pulmonary endocrine cells or cellular aggregates within the bronchiolar mucosa. When these nodular proliferations of neuroendocrine cells extend beyond the bronchiolar epithelium basement membrane, they are categorized as tumorlets; if these lesions exceed 5 mm in size, they are designated as carcinoid tumours.1 Although the classical WHO definition of DIPNECH was purely histological, the disease is frequently diagnosed based on clinical and radiological findings. This has been acknowledged by the latest WHO classification, which recognizes pathological DIPNECH (based solely on histological features) and clinical DIPNECH, defined by characteristic symptoms and radiological findings. In the latter, pathological confirmation of neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia (NECH)/tumorlets is considered desirable but not mandatory for diagnosis.6 Radiologically, DIPNECH is characterized by a mosaic attenuation pattern, bronchiolar wall thickening and bronchiectasis with mucous plugging. Additionally, numerous bilateral pulmonary nodules (<5mm) corresponding to tumorlets are frequently seen as well as nodules≥5mm that may correspond to carcinoid tumours. Symptomatic patients usually show signs and symptoms consistent with obstructive disease, presenting with a long history of cough, dyspnoea and wheezing (often misdiagnosed as asthma).7 As a subset of patients with DIPNECH present concurrently with tumorlets and >1 carcinoid tumours, DIPNECH is thought to represent a preinvasive lesion for LC. Importantly, progression of smaller pulmonary nodules to pathologically proven carcinoid tumours have been documented in patients with DIPNECH.3 It is noteworthy that the demographic characteristics of patients with DIPNECH are different from those with carcinoid tumours unrelated to DIPNECH. Compared with individuals with isolated carcinoid tumours, DIPNECH preferentially affects older women (median age, 68 years) with no past medical history of smoking.3 By contrast, carcinoid tumours unrelated to DIPNECH preferentially occur in younger patients without a marked sex predilection.8 It remains to be elucidated whether carcinoid tumours that develop in isolation or in the context of DIPNECH are oncogenetically divergent and, if so, whether they display distinct biological behaviour. As most of the literature focuses on the former, and studies directly comparing these scenarios are scarce, much remains to be clarified regarding DIPNECH-associated lung carcinoids, namely in terms of histogenetics, metastatic potential, and treatment targets and responses.

Our patient was an old, non-smoking woman with a diagnosis of clinical DIPNECH. The diffuse and dynamic nature of DIPNECH is challenging in terms of surveillance. In accordance with the available literature,3,9 periodic non-contrast chest CT scans were performed at 1–2 year intervals, which failed to show significant growth of the initially existing nodules but did reveal the development of new small nodules. Four years after the initial evaluation, she finally agreed to a transthoracic biopsy, which was consistent with a carcinoid tumour, supporting the diagnosis. Definitive classification into typical/atypical carcinoid was not possible, as this could only be made if a surgical resection had been performed, which was not the case.

The frequency of carcinoid tumours in patients with DIPNECH varies greatly in the literature. A previous study by Gorhstein et al. reported that all 11 cases of DIPNECH they analyzed showed at least 1 carcinoid tumour.10 Similarly, Mengoli et al. found at least 1 carcinoid tumour in all 19 cases of DIPNECH they examined.11 In a different study, Davies et al. analyzed 19 patients with DIPNECH, categorizing them in symptomatic (n=9) and asymptomatic disease (n=10); in all cases, the presence of tumorlets was confirmed, while progression to carcinoid tumours were reported in 4/9 and 8/10, respectively. In a recent study by Sun et al. which analyzed 24 cases of pathologically proven DIPNECH, most patients (87.5%) displayed>1 disorder along neuroendocrine spectrum (NECH/tumorlet/carcinoid), with nearly half exhibiting all 3 conditions.3

Most carcinoid tumours encountered in the context of DIPNECH are TC, but intermediate grade AC can also be found.12

On the other hand, metastatic spread of DIPNECH-associated lung carcinoids seems to be rare, although its characterization is hindered by the small number of reported cases.13 These include reports of metastasis to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, adrenal glands and liver.10,12,14 The liver seems to be the preferred metastatic site of “isolated” carcinoid tumours, followed by the bone and nervous system.15 More frequently, DIPNECH-associated metastatic disease seems to be linked to large (>1cm) and radiographically progressive tumours.9 This contrasts with the case described here, as no evident growth was detected during annual imaging.

An intriguing finding in this case was the divergent immunohistochemical profile of the lung and hepatic lesions. Immunostaining for TTF-1 is widely used to identify neoplasms of lung origin, although its expression in LC varies greatly in the literature, with positivity ranging from 0 to 94%.16,17 Greater expression of TTF-1 seems to be present in carcinoids with a peripheral location compared to central carcinoids.16 Transcription thyroid factor expression has also been reported in DIPNECH/tumorlets and associated carcinoids.11 On the other hand, CDX2 expression is more frequently in neuroendocrine tumours of gastrointestinal origin, although weak positivity has also been described in lung carcinoids.18

The absence of histochemical concordance between the lung lesion and liver metastasis led us consider the possibility of a syndromic background, such as multiple neuroendocrine neoplasm type 1 (MEN-1). However, given the patient's age and the absence of lab test results indicative of parathyroid hyperplasia/adenoma, we deemed this scenario unlikely. Furthermore, we found no evidence of different primary lesions on PET-Gallium, specifically none of GI origin. Hence, we consider the most likely hypothesis to be that a separate, concomitant, histogenetically distinct DIPNECH-associated carcinoid – different from the one biopsied – was responsible for the progression to metastatic disease.

Somatostatin receptor (SSTR) expression is the main reason for using somatostatin analogues (SSA) as both a diagnostic tool and an antiproliferative treatment in neuroendocrine tumours. It has been suggested that a SSTR-based imaging performed at diagnosis could help assess disease staging, evaluate somatostatin receptor expression and rule out neuroendocrine metastatic spread to the lungs from an extra-pulmonary origin.9 Of note, however, the sensitivity of SSTR-based imaging techniques appears to depend on lesion size: while they can detect carcinoid tumours concurrent with DIPNECH, they are less likely to identify NECH or tumorlets, which are likely below the resolution limit.3 This may at least partially explain the mismatch between CT and SSTR-PET findings that seems to occur frequently in DIPNECH.19 Additionally, as suggested by this case, there is a possibility of heterogenous expression of SSTR2 among different lesions in DIPNEHC-associated tumorlets/tumours, posing an additional challenge for diagnosis and therapeutic approach.

Functioning syndromes are rarely found in association with DIPNECH. A few cases of ectopic CS have been reported in patients with DIPNECH,20,21 as well as 3 patients with carcinoid syndrome.3 Additionally, a case of a patient with DIPNECH and acromegaly22 and another patient with DIPNECH and extrapulmonary signs of MEN-112 have been documented. In the case reported here, ACTH expression was detected in the lung lesion but not in hepatic metastasis, which may indicate that the metastatic spread and the development of a functional syndrome are governed by different and independent genetic pathways.

In most patients, DIPNECH is associated with stable or locally progressive disease, with only a few disease-related deaths reported to this date. Still, a minority may experience clinical decline with the development of severe airflow obstruction, leading to respiratory failure.23 Furthermore, the development of metastatic and/or functioning syndromes may interfere with the clinical course.

Given the slow progression and indolent nature of DIPNECH, conservative management is often advised. When the decision to treat is made, approaches include oral and inhaled steroids, beta agonists, lung resections and lung transplantation in severe cases.2 There is evidence, mainly coming from case reports and case series, that SSA such as octreotide or lanreotide may alleviate chronic respiratory symptoms.6–8 In addition to providing symptomatic palliation, SSA may inhibit tumour growth, and their use may be particularly pertinent in patients with relatively large tumours (e.g., 1–2cm in diameter) or radiographically progressive tumours.9 However, it remains to be established if SSA play a role in preventing the subsequent progression of DIPNECH to carcinoid tumours.

In the case described here, following years of clinical stability, the patient presented with a rapidly deteriorating health status primarily due to endogenous cortisol hypersecretion. It is estimated that 1–6% of lung carcinoids are associated with ectopic ACTH secretion (EAS), which accounts for 10–20% of CS cases.10 Particularly in cases of widely metastatic disease, EAS can present with an aggressive form of CS characterized by a sudden onset with severe features, including extremely elevated UFC levels, aggravated hypokalaemia, hypertension, diabetes and muscle weakness. Given the rapidly progressing CS, some of the typical signs, such as moon facies and violaceous striae, may be absent. Patients with ectopic ACTH-dependent CS patients face severe morbidity and a high mortality risk at presentation, largely due to an increased risk of opportunistic infections and heart failure. Nevertheless, if hypercortisolism control is successfully controlled, survival appears to be primarily influenced by tumour burden and comparable to that of non-functioning Lu-NETs. Therefore, controlling hypercortisolism should be a high priority as soon as the diagnosis has been established. Options include adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors and bi-adrenalectomy in severe and refractory cases. Some patients with ectopic ACTH secretion may also respond to SSA.8,11 Our patient exhibited a prompt reduction in cortisol levels even with very low doses of metyrapone, likely reflecting the effect of the SSA treatment as well.

There are no dedicated trials available for lung carcinoids to guide treatment, and most literature consists of case series or studies involving a mixed population of primary NET patients. Management of metastatic LC aims to control hormone-related symptoms and tumour growth, while preserving quality of life.24–26 SSAs are the first-line therapy for well-differentiated, SSTR-positive tumours.24 PRRT with 177Lu-DOTATATE is an emerging option for progressive, inoperable/metastatic SSTR-expressing NETs27,28 and everolimus is approved for advanced cases.24,25 LC generally have low proliferation index, so cytotoxic therapy often has limited effectiveness but may be considered, particularly for higher grade, SSTR-negative, rapidly progressive disease.26 In our patient, the therapeutic strategy prioritized medical control with metyrapone and SSA, with PRRT considered if needed.

Here, we describe an extremely rare case of clinical DIPNECH progressing to metastatic lung carcinoid which presented with ectopic Cushing's syndrome. This case highlights the importance of close and long-term surveillance, as well as the need for directed prospective trials for both DIPNECH and lung carcinoids to better assist and treat these patients.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.